Abstract

This work reveals a green combustion route for the synthesis of TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposites as photocatalysts for decolorization of Titan Yellow (TY) and Methyl Orange (MO) dyes at room temperature in aqueous solution concentration of 20 ppm under UV-light irradiation. We observed that the TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite shows superior photocatalytic activity for TY dye compared to pure TiO2 and Fe2O3. Rate constant (k) values of TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2–Fe2O3 for TY and MO are 0.0194, 0.0159, 0.04396 and 0.00931, 0.00772 0.0119 kmin−1 respectively. The surface area and pore volume of TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite were found to be 71.56 m2/g and 0.076 cm3/g, respectively as revealed by BET studies. From the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) plot, the mean pore diameter of TiO2-Fe2O3 nanoparticles was found to be 2.43 nm. Further, the TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite showed good electrochemical behavior as an electrode material for supercapacitors when compared to pure TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles resulted in stable electrochemical performance with nearly 100% coulombic efficiency at a scan rate of 10 mV/s for 1000 cycles. Interestingly, the novelty of this work is that the designed supercapacitors showed stable electrochemical performance even at 1000th cycle, which might be useful for rechargeable supercapacitor applications. The electrochemical properties of the nanocomposites were compared by the data obtained by cyclic voltammograms, charge-discharge tests and electrochemical impedance spectroscopic studies. These results demonstrated that the TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite showed stable performance compared to TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles at current density of 5 Ag−1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently electrochemical studies have gained significant attention due to energy and environment related issues. Since the discovery of TiO2 and its applications as photo-anode for battery, splitting of water, supercapacitor, dye removal etc1., many different metal oxides and electrodes have been explored to enhance the energy conversion efficiency. Amongst a variety of semiconductor metal oxides, hematite (α-Fe2O3) was found to be a good anode material for supercapacitor application, which could be attributed to its high solar-to-hydrogen efficiency, encouraging optical band gap (~2 eV), outstanding chemical strength as well as ease of availability in the nature. However, α-Fe2O3 exhibits low experimental performance compared with the theoretical values, which is possibly due to poor conducting and oxygen evolution properties in addition to short whole diffusion length. To overcome these problems, various synthetic methods have been tried in the recent past, to improve the experimental performance of α-Fe2O3.But, solution-based combustion method is a simple, low cost, energy saving, easy to control the surface morphology and particle size2. In addition, the materials prepared in this method are organic solvent free as we used water as solvent3,4,5.

The photocatalytic effectiveness of bare TiO2 is quiet less under direct solar light irradiation, despite of its superior physicochemical properties. This is possibly due to lack of visible light absorption as it exhibits high band gap energy (3.0–3.2 eV) and rapid electron-hole (e−/h+) recombination6. To reduce these drawbacks and improve structural stability, in the past several methods such as doping of hetero-junction with equivalent and/or different bandgap materials7, dyes sensitization8, noble and non-noble metal deposition9 were tried. Among those different methods explored, researchers tried to combine two or more semiconductor metal oxides having different band gaps10,11,12,13,14,15.

The present work was conducted on synthesis of TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposites from Aloe Vera gel assisted green combustion method. The synthesized nanocomposites were characterized for morphological nature, structural feature, surface area, pore size, surface composition, particle size and band gap energies. The TiO2-Fe2O3composites offered improved photocatalytic efficiency for the decolorization of TY and MO dyes under the UV light irradiation compared with that of base TiO2 and Fe2O3 nano materials. In addition, TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposites have been investigated in a preliminary way for potential use as an electrode material for supercapacitor applications.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanocomposites (Green method)

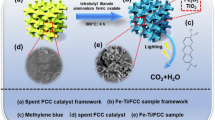

TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanocomposites were synthesized by applying Aloe Vera gel10 as a fuel via solution combustion method. Freshly collected 20 ml of Aloe Vera gel was added to 80 ml of deionized water. The resulting solution was filtered to get gel. This gel was used as a fuel for the synthesis of TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanocomposites. The metal precursor salts of Titanium (IV) isopropoxide (Sigma Aldrich) and Ferric nitrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O) (Sigma Aldrich) were placed in two separate silica crucibles containing 5 ml of Aloe Vera gel. These mixtures were stirred using magnetic stirrer. The blends were placed in a pre-heated muffle furnace maintained at 380 ± 10 °C. The arrangement was bubbled to yield a transparent gel. The gel then formed a white froth, which extended to fill the vessel. From that point, the surface of the froth started burning and continued quickly all through the volume, leaving a white powder with a great degree of porous structure. The energy discharged from the response raised the temperature to 1200 °C which aided to shape TiO2 and Fe2O3 NPs.

Synthesis of TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite

To load iron oxides on titanium dioxide impregnation method was used with small modification like; replacement of water in place of ethanol and using simple stirrer in place of ultra-sonication16, which decreases cost and toxicities towards organic solvent. Having made those important modifications, 0.1 M of TiO2-Fe2O3 oxide materials were synthesized by adding appropriate amount of TiO2 andFe2O3 powder in aqueous solution, with continuous stirring at 80 °C. At this point, homogenous woody colored solution was observed. In addition, on drop wise addition of ammonia (NH3) to shift the pH of the solution to basic, the same color, but, a heterogeneous (fall apart) type solution was observed. After drying and grinding the obtained product was subjected to calcination at 500 °C for 3 hours.

Characterization

The structural details of the nanocomposites were explored by using Shimadzu x-ray diffractometer (PXRD-7000) with CuKα (λ = 1.541 Ǻ). The vibrational spectra of the samples were recorded with a Shimadzu’s FTIR spectrophotometer (IR Affinity 1 S) using KBr pellets (400–4000 cm−1). The UV-Visible spectra of the samples were recorded in the range 200–800 nm using Shimadzu’s UV-2600, Uv-visible spectrophotometer. The morphological features and EDS analysis of all the samples were evaluated by using Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM/FIB-model Neon-40), at Nano manufacturing technology center (NMTC), CMTI, India. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method was utilized to calculate the specific surface areas of the samples in relative pressure (P/Po) range of 0.05–0.25. The pore-size distributions of the samples were determined by Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method. The total pore volume of nanocomposites was accumulated at a relative pressure of P/Po = 0.99. Sorption measurements of all the nanomaterials were carried out at −196 °C using a Quanta chrome instrument. The cyclic voltammetric studies were made using CHI604E potentiostat (tri-electrode system-sample as working electrode, platinum wire as counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl as reference electrode with 6.0 M KOH as electrolyte. The potential range utilized during these studies is ranging between −1.5 V and 0.9 V. The scanning has been carried out from 10 mV/s to50 mV/s. The potential range for recording the galvanostatic charge-discharge cycles is ranging between 0 and 0.7 V at a current density of 5 Ag−1. AC impedance measurements were carried out in the frequency range between 1 Hz and 1 MHz, with AC amplitude of 5 mV.

Results and Discussions

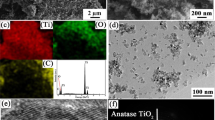

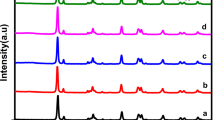

As shown in Fig. 1(a) the composition and structure of synthesized materials were identified by PXRD spectra and is in agreement with tetragonal (anatase) and rhombohedral phases of TiO2 and Fe2O3 respectively. The 2θ and Miller indices matching to 25.2° (101), 37.3° (004), 49.2° (200), 53.9° (105), 54.7° (211), 63.1° (204), 74.8° (215) are assigned to the tetragonal anatase TiO2 were matched with JCPDS Card No. (21–1272) and 24o (012), 33o (104), 36o (110), 41o (113), 49o (024), 54o (115), 58o (112), 63o (214), 64o (300) corresponds to Fe2O3 were well matched with JCPDS Card No. (00-001-1053). Confirming this, 33o (104), 36o (110) and 41o (113) peaks of Fe2O3 were observed on the spectra of TiO2-Fe2O3 heterojunction17,18,19,20,21. The structural drawings obtained from exploration and analysis software for TiO2 and Fe2O3 mercury crystal structure visualization are show in Fig. 1(b).

FTIR spectra of synthesized nanocomposite (TiO2-Fe2O3), recorded in the range of 400–4000 cm−1 are shown in the Fig. 2. The peak patterns appeared in the regions of 1074 cm−1, 1620 cm−1 and 3450 cm−1 corresponds to TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite. The reduction in the intensity of all the peaks was observed in case of composites after the incorporation of Fe2O3. The broad peaks appeared at 3450 cm−1 and 1620 cm−1 corresponds to –OH stretching and bending vibrations22.

These groups are possibly believed to influence the phase formation as well as in phase stabilization of all the nanocomposites23,24,25. The peak observed at460 cm−1 corresponding to Ti-O bond of TiO2, was found to be shifted to 525 cm−1 after the incorporation with Fe2O3where Fe-O stretching mode was clearly observed in the spectra. The peak at 1074 cm−1 is due to the C-O stretching vibration. The strong band below 700 cm−1 is assigned to Fe-O stretching mode. The band corresponding to Fe-O stretching mode of Fe2O3 is observed at 560 cm−1. Watchful observation of the SEM image of TiO2-Fe2O3 nanoparticles (Fig. 3) will reveal the presence of small Fe2O3 particles (circled in red color in Fig. 3) impregnated throughout the surface of TiO2 there by concluding that the larger particle is TiO2 and the smaller one is Fe2O3.

The SEM images of synthesized composites presented in Fig. 4(a–c) show that the morphology of the sample is somewhat porous and agglomerated, which is believed to be advantageous to enhance the properties. In addition, large and small particles of nearly equal sizes were observed in the images. The elemental confirmation in composites was done by using EDX measurements. The results revealed that the particle size of Fe2O3 is smaller than that of the TiO2 as observed in Fig. 4b. It is clear from the results that, increasing the calcination temperature causes the increase in the crystallinity of the material and helped to remove the impurities. Nevertheless, increasing the calcination temperature may also increase the crystal grain size26,27. In addition, the grain size which increases with surface roughness is believed to be advantageous in enhancing the contact surface area among electrode materials used in supercapacitors28.

Figure 5(a–c) shows the UV-Visible diffused reflectance spectra of TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 nanomaterials. As shown in the spectra, TiO2 exhibit a strong light absorbance edge close to 380 nm due to its inherent band gap (~3.21 eV) presented in the inset of Fig. 5a, which matches with the band gap of TiO2-Fe2O3 showing absorbance edges close to 500 nm (Eg = 2.0 eV), which is in agreement with the band-gap energy of Fe2O3 presented in the inset of Fig. 5b,while, TiO2-Fe2O3 edge found between 490 nm and 700 nm can be attributed to TiO2 and Fe2O3, with band gap energy (Eg = 2.08 eV) as presented in the inset of Fig. 5c. This shows that, significant improvement of visible light reflection and thus improvement in electrochemical reactions by means of visible light in addition to ultra-violet28,29. As suggested by30, owing to unique half-filed electronic configuration, Fe has the capacity to form new energy levels within the band gap range of TiO2 and reduces the gap between valence band and conduction band (red-shift of the absorption threshold).

The Kubelka - Munk function F(R) is utilized for examining the powders as given by Eq. (1):

where R: the reflectance, F(R): Kubelka-Munk function.

The optical energy gap can be calculated by using Tauc relation; the band gap (Eg) of semiconductor material can be calculated from the following equation:

where n = 1/2 and 2 for direct and indirect transitions respectively, for the optical energy gap was calculated using Tauc relation as in Eq. (2) gives the direct band31.

BET study

The optimal porosity and high surface area (low particle size) are the two crucial things for the synthesized TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite to be efficient catalyst. From Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) study, N2 adsorption-desorption measurement carried out at 77 K (Fig. 6), the synthesized TiO2-Fe2O3 nanomaterial was found to exhibit type IV isotherm with a sharp increase of the adsorbed volume starting from P/P0 = 0.97. This confirms the presence of well-developed mesoporous nanostructured nature of nanomaterial. The shifting of the hysteresis loop to the higher as the relative pressure (p/po) approaching to 1 indicates the presence of the micro porous particles with size greater than 50 nm. Furthermore, it also confirmed by the presence of mesoporous peaks around ~21, 44, 79, and 124 nm on the pore size distribution curve present as an inset in Fig. 6. The obtained BET surface area and pore volume value were found to be 71.56 m2/g and 0.076 cm3/g, respectively. The surface area of TiO2-Fe2O3 was found to be much higher relative to TiO2, which confirms the role of impregnated Fe2O3 in the enhancement of the specific surface area. From the equivalent, Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) pore-size, the obtained mean pore diameter for TiO2-Fe2O3 was found to be 2.43 nm.

Photocatalytic studies of dye under UV light irradiation

A circular glass reactor with surface area of 176.6 cm2 was utilized for the dye decolorization studies. A 125 W medium pressure mercury vapor lamp was used as UV light source. The samples were irradiated directly by focusing light into the reaction mixture at a distance of 23 cm. In a distinctive experiment ~60 mg of photocatalyst was dispersed in 250 ml of 20 ppm different dye solutions. The reaction mixture was subjected to vigorous stirring using magnetic stirrer for the entire period of experiment. The extent of dye decolorization was calculated by using the equation, Q = (Co − C)V/W,

where ‘Q’ is the extent of dye decolorization, Co and C are the concentrations of dye before and after decolorization, Vis the volume of the reaction mixture and W is the mass of photo-catalyst present in grams. The unit of Q is ppm ml mg−1. 6 ml aliquots of solution were drawn from the suspensions at definite time intervals and centrifuged straight away and filtered through a what men filter paper.

Decolorization of Titan Yellow (TY) and Methyl Orange (MO) dyes

Photocatalytic studies of the synthesized TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 nanoparticles were analyzed to review the decolorization performance at room temperature for the degradation of Titan Yellow (TY) and Methyl Orange (MO) dyesin aqueous solution with concentration of 20 ppm under UV-light irradiation with 60 mg of optimum catalysts dosage, as shown in Fig. 732.

Photo-decolorization of TY dye for synthesized nanoparticles is shown in the Fig. 7(a–c) with evidence of UV-Visible absorption spectra. The TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite was found to exhibitsuperior photo-decolorization results for TY dye solution when compared to TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles respectively. In the case of TY dye solution, the TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite exhibited 92.98% dye decolorization as shown in Fig. 7c, which is superior performance compared to 71.67 and 62.89% for TiO2 and Fe2O3, respectively as revealed in Fig. 7a,b at 405 nm. Photocatalytic activity as presented in Fig. 7(a–c) revealed that the photo-decolorization effects in the presence of the TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite were found to be more efficient and reached the maximum adsorption capability around 53.58%. Up to 60 min of UV light irradiation during the photocatalytic activity, the synthesized composite continued to exhibit the best decolorization capability with 53.58% decolorization of the MO dye solution as shown in Fig. 7c. TiO2 nanoparticles also exhibited good decolorization ability for the TY dye solution with a final removal of organic dye around 45.02% at 460 nm compared to decolorization ability of Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Fe2O3 nanoparticles ability to remove MO dye was found to be 38.67% as shown in Fig. 833,34,35,36.

In addition to that, TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite exhibited superior photocatalytic efficiency of 92.98% for the azo dye group under UV light irradiation for a period of 60 min. In the case of MO dye solutions, the TiO2-Fe2O3 composite exhibited very less photocatalytic activity of 53.58% after 60 minutes of irradiation which is found to bellower than that of TiO2 and Fe2O3 for MO organic dye after 60 minutes under UV light irradiation. From these results, it can be concluded that TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite is an excellent photocatalyst for the decolorization of TY organic dye with high photo-decolorization activity which can be attributed to e−h+ recombination, generation of hydroxyl and superoxide radicals.

Rate constant k values for TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2–Fe2O3 were found to be 0.0194, 0.0159, 0.04396 for TY and 0.00931, 0.00772 and 0.0119 min−1 for MO dyes respectively. It clearly reveals that TiO2–Fe2O3 nanocomposite is better nanomaterial for TY dye showing enhanced photocatalytic activity compared to pure TiO2 and Fe2O3 synthesized nanoparticles. In addition, the noticeable rate constant k of the TiO2–Fe2O3 nanocomposite for MO dye is 0.44 times and 2.26 times to that of TiO2–Fe2O3nano-composite for TY dye respectively and rate constant can be ranked in the order of Fe2O3(MO) <TiO2(MO) <TiO2–Fe2O3(MO)<Fe2O3(TY) <TiO2(TY) <TiO2–Fe2O3(TY) was observed in Tables 1 and 2. High separation and transportation rate of the e−h+ pairs, and reduction of band gap are responsible for higher photocatalytic activity of TiO2–Fe2O3 nanocomposite which could be attributed to synthetic method and modified surface morphology of synthesized nanoparticles37.

Tables 1 and 2 presents kinetics parameters of TY and MO at various time periods (from 0 to 60 min) at 405 and 460 nm respectively, it evidently shows that the degradation of dye increased with time in the presence of synthesized nanoparticles under UV light irradiation38. TY dye decolorization of 92.98% for TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite is very significant. From the log C/Co values, it is also evident for decolorization of dyes under UV light irradiation time, exhibiting linear relationship based on the following equation:

where Co is concentration of dye at time t = 0 min, C is a concentration of dye at particular time t and k is first order rate constant. This follows first order rate kinetics, photocatalytic decolorization efficiency of dye is calculated by using the following equation as efficiency (%) of photo-decolorization.

where Co is the initial concentration of the dye solution, C is a residual concentration of the dye in solution after degradation in equilibrium.

The photo-decolorization of dye in the presence of photocatalyst occurs as evidenced by little change in the absorption peak after UV light irradiated for 60 min39. Figure 9(a,b) showed plots of C/C0 for the decolorization of TY and MO, where Co is initial concentration of dye and C is the concentrations of the dye at time t, respectively. It is undisputed that the decolorization rate of TY and MO followed by the order of Fe2O3(MO) <TiO2(MO) <TiO2-Fe2O3(MO)<Fe2O3(TY) <TiO2(TY) <TiO2-Fe2O3(TY) after the 60 min irradiation time. The result indicated that the decolorization efficiency of TY could be enhanced in the presence of TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite photocatalytic system as compared to pure TiO2 and Fe2O3.

The electronic arrangement of the semiconductor heterojunctions is categorized into straddling gap, staggered gap, and broken gap. Among these, the staggered band structure has high probability in the direction of electron-hole (e−h+) separation and improving capacity of the photocatalytic reaction. This happens because of the creation of a depleted layer at the interface of the two (which produces an electric field) and then the diffusion of the photogenerated e−h+ out of the depletion layer takes places. Thus matching the band gaps of TiO2 and Fe2O3 play a significant role in the mechanism. During heterojunction, as shown in Fig. 10, when the Fermi level (FL) of one n-type semiconductor core in contact with the FL of the other n-type, the depletion layer that produces electric field was created.

The activated electric field drives the diffusion of the photogenerated e–h+ out of the depletion layer and results in activation of the photocatalysis efficiency. In the higher energy region, some of the photogenerated e−s with a higher energy level than the CB position of TiO2 could thermodynamically transfer to the CB of TiO2 (Fig. 11), while photogenerated holes build up in the valence band of Fe2O3. The negatively charged e−s in the conduction band of TiO2 will further transfer to TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite via Fe2O340.

These negatively charged electrons, which are believed to react with O2 to form the superoxide anion (O−2) in the dye solution and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), while positively charged holes are accompanied in the TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite of the valence band, will respond with OH−groups present on the surface of the catalyst, produces reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH.). The reactions can be described as follows:

Thus, the enhanced photocatalytic decolorization effectiveness seen in the synthesized nano materials is basically attributed to more effective separation of photogenerated e− and h+ pairs41,42.

Electrochemical Studies

Electrochemical behavior of the synthesized TiO2, Fe2O3 nanoparticles and TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite

The appearance of oxidation peak during the charging and reduction peak during discharge process is usual for CV plots. CV was first performed in a range of −1.6 V and 0.9 at a scan rate of 10 mV/s as shown in Fig. 12.

The CV plot of TiO2 NPs shows one oxidation and reduction peak due to interconversion of Ti2+ and Ti4+, similarly same behavior can be seen in Fe2O3 NPs due to Fe2+ and Fe4+. But in the TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite pair of oxidation-reduction peaks appears because of red-ox process of Ti-Fe composite. This behavior indicates that the capacity is mainly from the pseudo capacitance, which is based on the red-ox mechanism43.

For the nickel electrodes, the specific capacitance can be calculated from the CV curves, according to the following Eq. (4):

where i, r and m are the current, the scan rate and mass of the prepared TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 electrodes. The specific capacitance values were calculated to be 601 Fg−1, 385 Fg−1 and 879 Fg−1 for electrodes of TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 electrodes, respectively, at a scan rate of 10 mVs−1.

The relative heights of the peaks for each sample are found to be different. The observed discrepancy can be due to the difference in the effective surface area and amount of active material. The specific capacitance of electrodes was calculated by the following equation43,44,45:

where, i is the applied current, ΔV is the potential range, Δt is the time of a discharge cycle and m is the mass of the TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite. The specific capacitance values of pure TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 electrodes were calculated and found to be 585 Fg−1, 372 Fg−1 and 862 Fg−1. TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite electrode exhibited highest capacitance.

The life cycle stability of TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 electrodes were performed using galvanostatic charge-discharge curves (Fig. 13) measured at a current density of 5 Ag−1 for 1000 cycles within the potential window of 0–0.6 V (for TiO2), 0–0.5 V (for Fe2O3) and 0–0.7 V (for TiO2-Fe2O3) vs. Ag/AgCl. TiO2-Fe2O3 electrode exhibited very good stability after 1000 cycles.

Galvanostatic charge–discharge curves of the TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 at various constant current densities are shown in Fig. 14. An ideal capacitive behavior is confirmed due to the appearance of triangular shaped curves in charge–discharge diagrams. The better storage rate ability of the synthesized materials was confirmed with an increase in integrated area on the current-potential axis45. The TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite has the longest charge and discharge time, informative its maximum specific capacitance, which is in agreement with the consequences of Fig. 13, it confirms the voltage as a function of cycle number respectively revealing an opposite performance amongst them.

EIS measurements for TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2-Fe2O3 electrodes were carried out with three electrode assembly in 1 M KOH within the frequency range between 1 MHz and 100. The EIS spectra can be seen in Fig. 15. The real component Zreal reveals the ohmic properties while the imaginary part (Zimg) relates to the capacitive properties46. Typically, semicircles with larger radii refer to higher charge transfer resistance of the electrodes47. Therefore, EIS result concludes that the charge transfer resistance Rct of TiO2-Fe2O3electrode is much smaller than that of TiO2 and Fe2O3, indicating more effective incorporation of TiO2-Fe2O3nanostructures of this sample in the charge transfer process. Thus EIS results confirmed lower charge transfer resistance for TiO2-Fe2O3 electrode as compared to TiO2 and Fe2O3 electrode, and hence possess more capacitive properties48.

Conclusions

We efficiently synthesized TiO2, Fe2O3 NPs and TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposites via green combustion route with Aloe Vera gel as a fuel. The diffraction peaks of TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles were well matched with tetragonal (anatase) and rhombohedral phasesas investigated by PXRD patterns. Furthermore, FTIR spectroscopy confirmed the formation of TiO2 and Fe2O3nanoparticles. The presence of the porous and agglomerated surfaces of the TiO2 as well as Fe2O3 and spherical for TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposites were observed through SEM and band gap energy of TiO2, Fe2O3 nanoparticles and TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposites were found to be 3.21, 2.0 and 2.08 eV respectively as confirmed by using DRS spectrum. The significant increase in the surface area of the nanocomposite as revealed by BET study confirmed the enhancement of adsorption capacity of pollutants and photocatalytic efficiency by impregnated TiO2-Fe2O3. The photo-decolorization studies revealed that TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite is a good photocatalyst for the decolorization of Titan Yellow (TY) and Methyl Orange (MO)organic dyes with high photo degradation activity compared to TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles. The optimal conditions for this study included at room temperature in aqueous solution concentration of 20 ppm and catalyst dosage 60 mg under UV-light irradiation. The rate constants can be ranked in the order of Fe2O3(MO) < TiO2(MO) < TiO2–Fe2O3(MO) < Fe2O3(TY) < TiO2(TY) < TiO2–Fe2O3(TY). The synthesized TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposites showed excellent electrochemical behavior as electrode material for supercapacitance applications. A superior electrochemical response which includes enhanced charge/discharge capacity and cycling stability when compared to pure TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles resulted in stable electrochemical performance with nearly 100% coulombic efficiency at a high current density of 5 A/g for 1000 cycles. Interestingly, the novelty of this work is that the designed supercapacitors showed stable electrochemical performance even at 1000 cycles, which can be beneficial for rechargeable supercapacitor applications.

References

Chai, X. et al. 3D ordered urchin-like TiO2@Fe2O3 arrays photo anode for efficient photo electrochemical water splitting. Appl. Sur. Sci. 470, 668–676 (2019).

Xiaomin, T. et al. Chemical coagulation process for the removal of heavy metals from water: a review. Desalin. Water Treat. 57, 1733–1748 (2015).

Wang, D. K., Elma, M., Motuzas, J., Hou, W. & Xie, F. Rational design and synthesis of molecular-sieving, photocatalytic, hollow fiber membranes for advanced water treatment applications. J. Memb. Sci. 524, 163–173 (2016).

Abebe, B. & Murthy, H. C. A. Summary on Adsorption and Photocatalysis for Pollutant Remediation: Mini Review. J. Encapsulation Ads. Sci. 8, 195–209 (2018).

Pype, M., Lawrence, M. G., Keller, J. & Gernjak, W. Reverse osmosis integrity monitoring in water reuse: The challenge to verify virus removal e A review. Water Res. 98, 384–395 (2016).

Gómez-pastora, J. et al. Review and perspectives on the use of magnetic nano photocatalysts (MNPCs) in water treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 310, 407–427 (2017).

Chen, F. Synergistic effect of CeO2 modified TiO2 photocatalyst on the enhancement of visible light photocatalytic performance. J. Alloy. Compd. 714, 560–566 (2017).

Wu, L. et al. Characterization and photocatalytic properties of nano-Fe2O3–TiO2 composites prepared through the gaseous detonation method. Ceram. Int. 43, 14334–14339 (2017).

Wang, D. et al. Sunlight photocatalytic activity of polypyrrole – TiO2 nanocomposites prepared by ‘in situ’ method. Catal. Commun. 9, 1162–1166 (2008).

Gao, Q., Wu, X. & Fan, Y. Dyes and Pigments the effect of iron ions on the anatase erutile phase transformation of titania (TiO2) in mica titania pigments. Dye. Pigment. 95, 96–101 (2012).

Liu, H., Shon, H. K., Sun, X., Vigneswaran, S. & Nan, H. Preparation and characterization of visible light responsive Fe2O3 – TiO2 composites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 257, 5813–5819 (2011).

Wang, T. Orthogonal synthesis, structural characteristics and enhanced visible-light photocatalysis of mesoporous Fe2O3/TiO2 hetero structured microspheres. Appl. Surf. Sci. 311, 314–323 (2014).

Ghorai, T. K., Chakraborty, M. & Pramanik, P. Photocatalytic performance of nano-photocatalyst from TiO2 and Fe2O3 by mechanochemical synthesis. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 8158–8164 (2011).

Li, R., Jia, Y., Bu, N., Wu, J. & Zhen, Q. Photocatalytic degradation of methyl blue using Fe2O3/TiO2 composite ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 643, 88–93 (2015).

Tu, Y., Huang, S., Sang, J. & Zou, X. Preparation of Fe-doped TiO2 nanotube arrays and their photocatalytic activities under visible light. Mater. Res. Bull. 45, 224–229 (2010).

Zhan, S. Mesoporous Fe2O3 -doped TiO2 nanostructured fibers with higher photocatalytic activity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 355, 328–333 (2011).

Wenjuan, L., Liang, R., Hu, A., Huang, Z. & Zhou, Y. N. Generation of oxygen vacancies in visible light activated one-dimensional iodine TiO2 photocatalysts. RSC Adv. 4, 36959–36966 (2014).

Xia, L. Y. Y. Core-Shell Structured α-Fe2O3@TiO2 Nanocomposites with Improved Photocatalytic Activity in Visible Light Region. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 18627–18634 (2013).

Mahadik, M. A. Visible light catalysis of rhodamine B using nanostructured Fe2O3, TiO2 and TiO2/Fe2O3 thin films. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 133, 90–98 (2014).

Wang, Z., Liu, Y., Huang, B., Dai, Y. & Lou, Z. Progress on extending the light absorption spectra of photocatalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 2758–2774 (2014).

Mamba, G. & Mishra, A. K. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) nanocomposites: A new and exciting generation of visible light driven photocatalysts for environmental pollution remediation. Appl. Catal. B, Environ. 198, 347–377 (2016).

Li, X., Yu, J. & Jaroniec, M. Chem Soc Rev Hierarchical photocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2603–2636 (2016).

Wahyuningsih, S., Ramelan, A. H., Tan, F. H. & Zhang, Q. M. The Influence of Fe2O3 Addition on the TiO2 Structure and Photoactivity Properties. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 333 (2018).

Abebe, B. & Murthy, H. C. A. Synthesis and Characterization of Ti-Fe Oxide Nanomaterials for Lead Removal. J. Nanomater., Article ID 9651039 (2018).

Sharma, B., Boruah, P. K., Yadav, A. & Das, M. R. TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite hetero junction for superior charge separation and the photocatalytic inactivation of pathogenic bacteria in water under direct sunlight irradiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6, 134–145 (2018).

Shojaie, A., Fattahi, M., Jorfi, S. & Ghasemi, B. Synthesis and evaluations of Fe3O4–TiO2–Ag nanocomposites for photocatalytic degradation of 4 chlorophenol (4-CP): effect of Ag and Fe compositions. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 0123456789, 24–26 (2018).

Jin, H., Zhao, X., Wu, Z., Cao, C. &Guo, L. Supercritical water synthesis of nano-particle catalyst on TiO2 and its application in supercritical water gasification of biomass.J. Exp. Nanosci., 8080 (2016).

Y. P. L. & Mehrvar, M. Photocatalytic Treatment of an Actual Confectionery Wastewater Using Ag/TiO2/Fe2O3: Optimization of Photocatalytic Reactions Using Surface Response Methodology. Catalysts. 8, 409 (2018).

Habibi, M. H. & Karimi, B. Application of impregnation combustion method for fabrication of nanostructure CuO/ZnO composite oxide: XRD, FESEM, DRS and FTIR study. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 20, 1566–1570 (2014).

Abbas, N. et al. Sol – gel synthesis of TiO2 -Fe2O3 systems: Effects of Fe2O3 content and their photocatalytic properties. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 39, 112–120 (2016).

Pratapkumar, C. et al. White light emitting magnesium aluminate nanophosphor: Near ultra violet excited photoluminescence, photometric characteristics and its UV photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys and Compounds 728, 1124–1138 (2017).

Li, B., Zhao, Z., Gao, F., Wang, X. & Qiu, J. Mesoporous microspheres composed of carbon-coated TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed (001) facets for improved visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 147, 958–964 (2014).

Liu, S., Zhu, J., Guo, X., Ge, J. & Wu, H. Preparation of -Fe2O3 – TiO2/fly ash cenospheres photocatalyst and its mechanism of photocatalytic degradation.Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 484, 434–440 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Dendritic α-Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposites with improved visible light photocatalytic activity. Chem. Phys. 18, 9176–9186 (2016).

Zhang, Z. et al. Facile one-step synthesis of TiO2/Ag/SnO2 ternary hetero structures with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. Sci. Rep. 8, 10532 (2018).

Wu, W., Wu, Z., Yu, T. & Jiang, C. Recent progress on magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, surface functional strategies and biomedical applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 16, 23501 (2015).

Renuka, L. et al. A simple combustion method for the synthesis of multi-functional ZrO2/CuO nanocomposites: Excellent performance as Sunlight photocatalysts and enhanced latent fingerprint detection. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 210, 97–115 (2017).

Bayram, K., Gedik, N., Selin, P. & Serhan, A. Band gap engineering and modifying surface of TiO2 nanostructures by Fe2O3 for enhanced-performance of dye sensitized solar cell. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 31, 363–371 (2015).

Li, Y. R., Jia, W. J. & Zhen, Q. Photocatalytic Degradation and Pathway of Oxytetracycline in Aqueous Solution by Fe2O3-TiO2 Nanopowders. RSC Adv. 5, 40764–40771 (2015).

Subramonian, W., Wu, T. Y. & Chai, S. Using one-step facile and solvent-free mechanochemical process to synthesize photoactive Fe2O3-TiO2 for treating industrial wastewater. J. Alloys Compd. 695, 496–507 (2017).

Nasirian, M., Bustillo-lecompte, C. F. & Mehrvar, M. Photocatalytic efficiency of Fe2O3/TiO2 for the degradation of typical dyes in textile industries: Effects of calcination temperature and UV- assisted thermal synthesis. J. Environ. Manage. 196, 487–498 (2017).

Mirmasoomi, S. R., Ghazi, M. M. & Galedari, M. Photocatalytic degradation of diazinon under visible light using TiO2/Fe2O3 nanocomposite synthesized by ultrasonic-assisted impregnation method. Sep. Purif. Technol. 175, 418–427 (2017).

Gurav, K. V. et al. Room temperature chemical synthesis of Cu(OH)2 thin films for supercapacitor application. J. Alloy Compd. 573, 27–31 (2013).

Liu, T. et al. Miniature supercapacitors composed of nickel/cobalt hydroxide on nickel-coated silicon microchannel plates. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 19093–19100 (2011).

Ravikumar, C. R. et al. CuO embedded β-Ni(OH)2 nanocomposite as advanced electrode materials for supercapacitors. J. Alloys and Compounds. 738, 332–339 (2018).

Ravikumar, C. R. et al. Influence of zinc additive and pH on the electrochemical activities of β-nickel hydroxide materials and its applications in secondary batteries. J. Energy Storage. 9, 12–24 (2017).

Anil Kumar, M. R. et al. Green engineered nano MgO and ZnO doped with Sm3+: Synthesis and a comparison study on their characterization, PC activity and electrochemical properties. J. Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 127, 127–139 (2019).

Shinde, S. K., Dubal, D. P., Ghodake, G. S. & Fulari, V. J. Morphological modulation of Mn: CdSe thin film and its enhanced electrochemical properties. J. Electroanal. Chem. 727, 179–183 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R. Anil Kumar Photocatalytic designed the experiments and wrote the main manuscript text. B. Abebe synthesis of nanomaterials. H.P. Nagaswarupa XRD analysis. H.C. Ananda Murthy SEM and EDAX analysis. C.R. Ravikumar Cyclic voltammetry, AC impedance, Charge-discharge and supervised the work. Fedlu Kedir Sabir DRS and FTIR analysis. All authors contributed to the scientific discussion and manuscript revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, M.R.A., Abebe, B., Nagaswarupa, H.P. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic and electrochemical performance of TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite: Its applications in dye decolorization and as supercapacitors. Sci Rep 10, 1249 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58110-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58110-7

This article is cited by

-

Studies on photoluminescence, electrochemical sensors, and photocatalysis using Ho3+-doped MgAl2O4 nanophosphors

Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society (2024)

-

Optimization of Methylene Blue Removal from Aqueous Media by Photocatalysis and Adsorption Processes Using Coconut Biomass-Based Composite Photocatalysts

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2024)

-

The synthesis of cubic Fe2O3·TiO2 material and its application in heterogeneous photo-Fenton degradation of dyes under visible light

Journal of Nanoparticle Research (2024)

-

A Benign Approach for Sunlight and UV Driven Photocatalytic Applications of Green Synthesized Novel Calcium Magnesium Aluminate Nanoparticles for Acid Red-88 Dye Degradation

Chemistry Africa (2024)

-

Study of the morphological, structural and photophysical properties of surfactant modified nano-zero valent iron: electrochemical determination of metal ions and photocatalytic degradation of organic dye

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.