Abstract

Cranial radiation therapy is associated with white matter-specific brain injury, cortical volume loss, mineralization, microangiopathy and neurocognitive impairment in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In this retrospective cross-sectional analysis, neurocognitive testing and 3 T brain MRI’s were obtained in 101 survivors treated with cranial radiation. Small focal intracerebral hemorrhages only visible on exquisitely sensitive MRI sequences were identified and localized using susceptibility weighted imaging. Modified Poisson regression was used to assess the effect of cranial radiation on cumulative number and location of microbleeds in each brain region, and multiple linear regression was used to evaluate microbleeds on neurocognitive outcomes, adjusting for age at diagnosis and sex. At least one microbleed was present in 85% of survivors, occurring more frequently in frontal lobes. Radiation dose of 24 Gy conveyed a 5-fold greater risk (95% CI 2.57–10.32) of having multiple microbleeds compared to a dose of 18 Gy. No significant difference was found in neurocognitive scores with either the absence or presence of microbleeds or their location. Greater prevalence of microbleeds in our study compared to prior reports is likely related to longer time since treatment, better sensitivity of SWI for detection of microbleeds and the use of a 3 T MRI platform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cranial radiation therapy (CRT) has been associated with cognitive impairment in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)1,2. Adult survivors of childhood ALL treated with 24 Gy CRT were six times more likely to develop cognitive impairments than survivors treated with chemotherapy only in one large cohort study3. Radiation therapy has been associated with structural changes in the brain including white matter injury, cortical volume loss, mineralization, and microangiopathy4,5, which in turn were related to neurocognitive impairments6.

The incidence of microbleeds in the general population is between 5–35% with large variance reflecting increasing prevalence with age7,8. In a study using early susceptibility imaging techniques, Chan and colleagues reported microbleeds in 55% of 40 leukemia survivors treated with CRT at an average duration of 12.2 years from diagnosis9. To our knowledge, there are no studies examining the associations between microbleeds and neurocognitive function in long-term survivors of childhood ALL. However, in a multi-institutional cohort of 149 pediatric brain tumor survivors, those who had CRT had a cumulative incidence of microbleeds of 48.8% at 5 years; in this series the presence of microbleeds in frontal lobes was associated with worse executive function and in temporal lobes with poorer verbal memory10. Moreover, in a longitudinal study of 959 Chinese volunteers without cancer who were 50 years of age or older, lobar microbleeds, but not deep or infratentorial microbleeds, were associated with impaired visuospatial executive function using high field (3 T) susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI)11.

The aims of the current study were to evaluate survivors of childhood ALL during adulthood using 3 T MRI and a well-established high quality microbleed sensitive sequence to examine if relatively low doses of cranial radiation were associated with the development of microbleeds, and to investigate if the presence, frequency and/or location of microbleeds was associated with neurocognitive impairment.

Results

Of the 101 survivors of ALL included in this study (55 females, mean [range] time since diagnosis 27.6 [19.18–46.01] years), 64 (63.4%) had ≤18 Gy cranial irradiation. High-dose intravenous methotrexate was administered to 49.5% and intrathecal methotrexate to 97% of the survivors. Most survivors were college graduates or had taken classes at the college level (67.4%) with only 9.2% having not completed high school. Most survivors were full-time employed (76.0%) with only 17.7% unemployed at the time of testing (Table 1).

Eighty-five percent (N = 86) of survivors in this study had one or more microbleeds. Microbleeds occurred more frequently in the frontal lobes, followed by temporal lobes, the parietal/occipital lobes, sub-lobar/midbrain and finally the cerebellum, pons and brainstem (Table 2). No significant difference in the mean number of microbleeds was found between white matter and grey matter (N = 64, SE 0.358, p = 0.053).

A CRT dose of 24 Gy conveyed a 5-fold greater risk (RR 5.15, 95% CI 2.57–10.32) of having 6 or more microbleeds than 18 Gy (Table 3). A CRT dose of 24 Gy conveyed a 2-fold greater risk than 18 Gy for the presence of frontal lobe microbleeds (relative risk [RR] 1.92, 95% confidence interval [95%CI] 1.41–2.61) and temporal lobe microbleeds (RR 2.12, 95% CI 1.52–2.95), and a nearly 3-fold greater relative risk for an occipital/parietal lobe microbleeds (RR 2.73, 95% CI 1.72–4.31). We found no significant increased risk for microbleeds with increasing time since diagnosis (RR 1.1, 95% CI 0.98–1.23), cumulative vincristine (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96–1.00) or cumulative asparaginase dose (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.94–1.04).

Survivors demonstrated worse performance on 12 neurocognitive outcomes and two self-report outcomes compared to population norms, and these outcomes were selected for subsequent analysis (Table 4). Neurocognitive scores and self-reported outcomes were not associated with CRT dose after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Table 5). No associations were found with location of microbleeds and neurocognitive testing (Table 6). An exploratory analysis found that occipital/parietal lobe microbleeds were associated with self-reported problems in shifting between tasks (SE 0.24; p = 0.031) and working memory (SE 0.27; p = 0.033), while cerebellum and brainstem microbleeds were associated with self-reported working memory problems (SE 0.27; p = 0.005). The total number of microbleeds was not significantly associated with any of the selected neurocognitive tasks, adjusting for age at diagnosis and sex.

To further explore associations between cerebral microbleeds and cognitive impairment, we conducted sensitivity analyses comparing 15 survivors with no microbleeds to the 15 survivors with 10+ microbleeds (Table 7). No difference was found in the neurocognitive scores between those two groups. Moreover, no association was found between the number, duration or severity of hypertension and microbleed count and no association was found between high-dose methotrexate, intrathecal methotrexate and microbleed count. Therefore, methotrexate exposure was excluded in the final analysis.

Discussion

This study used 3 T MRI and SWI imaging to demonstrate that the incidence of cerebral microbleeds in survivors of ALL, 19 years or more from diagnosis, is greater than previously described. Microbleeds were present in 85% of our survivors compared to only 55–57% in the previous reports9,12. The greater incidence of microbleed’s reported in our study is likely related to the greater time since diagnosis and treatment, the greater sensitivity of SWI for detection of microbleeds and the use of a 3 T MRI platform for our study. Prior investigations included 1.5 T MRI and T2* GRE sequences and as such had lower sensitivity for smaller microbleeds13. Similar to our study, Neu et al., using SWI on a 3 T MRI platform, found that 36 of 40 (90%) of brain tumor survivors treated with cranial radiation had microbleeds at a mean of 13.5 years after diagnosis14 and the total number of microbleeds correlated with greater whole brain radiation dose and time since diagnosis. A recent study of 113 adult brain tumor patients treated with cranial radiation who received serial SWI’s at 7 T were found to have an 18% increase in volume and 11% increase in number of microbleeds per year15.

Morrison et al., however, found no association between maximum radiation dose to the brain and microbleed development in adult brain tumor patients15. Similarly, in a previous study of 90 children treated with cranial radiation for a mixture of CNS tumors and leukemias, no significant difference in cerebrovascular abnormalities were found between patients treated with low (18 Gy) or high (at least 32 Gy) doses of CRT4. In contrast to these studies we found that higher CRT doses (24 Gy vs 18 Gy) conveyed a greater risk for the microbleed development. The difference between our findings and those of Morrison et al. may be related to our survivors’ exposure to radiation as children as opposed to adulthood in the Morrison study. Interestingly, Morris et al. found that multiple neurosurgical resections conveyed a greater risk for the development of microbleeds15. This may also explain the differences seen between brain tumor and ALL survivors. Additionally, the participants in the Koike et al. study were only evaluated 10 years or less from time of diagnosis while the survivors in our cohort were imaged between 19 to 46 years after diagnosis. With a greater time since treatment, microbleeds may differentially develop based on cranial radiation dose. Cranial radiation induced microbleeds have been shown to be produced by the release of vEGF induced by radiation exposure and develop as early as three months after exposure and can continue to develop over decades16,17. In the context of the previous studies, our findings would suggest that the natural progression of radiation induced microbleeds in childhood ALL survivors is to increase in number with age and that CRT dose may be related to the amount of increase.

We found no evidence that the increased number or location of the microbleeds was associated with neurocognitive test outcomes in survivors. There is limited data in the literature regarding the association between microbleeds in childhood ALL survivors and neurocognitive outcomes. In the only other study of ALL survivors to investigate possible neurologic symptoms associated with microbleeds, only two of 43 patients with focal susceptibilities on MRI presented with neurologic manifestations12. One was associated with a meningioma related to the patient’s clinical presentation and the other had a microbleed in the frontal lobe that was not correlated with the presenting clinical symptoms. This supports our finding that there is no relationship between number or location of microbleeds and neurocognitive outcomes. In addition, we found no difference in cognitive outcomes between survivors who had received 18 and 24 Gy although both groups demonstrated significantly lower neurocognitive performance compared to age adjusted norms.

A prior study of pediatric brain tumor survivors found microbleeds were associated with lower executive function and verbal memory scores10. Similar to the Chan et al. and Faraci et al. investigations in ALL patients, the Roddy et al. study did not use the most sensitive technique for microbleed detection (SWI) in all subjects. Additionally, some imaging was performed on less sensitive 1.5 T MRI platforms which could have led to under detection of microbleeds18. Further, it is possible that the nonuniform MRI parameters used in the Roddy et al. study led to undercounting of smaller cerebral microbleeds, which introduced non-random bias in their data and affected detection of microbleed associations with neurocognitive measures. Our results corroborate those found in a study of adults with mild cognitive impairment and cerebral microbleeds, conducted using 3 T MRI and SWI sequences, which found no significant associations between cognitive decline and the number or location of the microbleeds8.

Interestingly, survivors self-reported difficulties with mentally shifting between tasks and working memory problems were associated with microbleeds in the occipital/parietal lobe and cerebellum, midbrain and pons. There are limited data in the literature looking at the association between self-reported outcomes and microbleeds in any population. One possible explanation is that this association could be the result of lesions in the parietal lobe impacting survivor’s self-perception or self-image19. However, our study could be limited in that the neurocognitive domains tested were not adequate to capture the cognitive problems self-reported by the survivors or that these were spurious results. Additionally, although we did not find any association between hypertension and the number of microbleeds, we cannot exclude that additional comorbidities associated with aging may have greater impact on cognitive deficits in the aging survivor cohort than microbleeds. It is possible that the size of the microbleeds might influence neurocognitive function. However, the physics of susceptibility imaging limits our ability to estimate the size of the microhemorrhage, as the susceptibility field only represents the concentration of susceptibility inducing constituents and not necessarily the spatial distribution of those components20.

In adult survivors of childhood ALL, routine assessment of radiation induced cerebral microbleeds may not be warranted to monitor their neurocognitive impact. Our data would indicate that although the number of microbleeds increases with age, lifestyle and chronic aging conditions may contribute more to cognitive decline in this population than cumulative microbleed burden. A prospective longitudinal study would be needed to determine if survivors suffer cognitive declines over time and if those declines correlate better with chronic health conditions or microbleed accumulation or progression. This would allow better determination of the specific risk factors predisposing survivors to cognitive decline in later years.

Methods

Study design and participants

A random subset of childhood ALL survivors was recruited from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study to examine the impact of CRT on brain imaging outcomes. Survivors were eligible if they were treated with cranial radiation at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, were ≥10 years from cancer diagnosis and were ≥18 years of age. Participants were excluded if they developed a secondary cancer following additional cranial radiation treatment or non-treatment related CNS injury or disease prior to assessment. Of the 153 potentially eligible survivors, 127 were determined eligible for this study. Thirteen survivors refused participation, six withdrew from the study prior to completion of outcome measures and seven were excluded due to poor image quality, resulting in 101 MRI examinations of the brain for analysis. One participant with 716 microbleeds was a significant outlier and was excluded from the analyses. Specific chemotherapy regimens differed according to treatment era in this cohort. However, all survivors where treated with cranial radiation, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, 6-mercapitopurine, and methotrexate. Only two survivors did not receive asparaginase and only one survivor received daunomycin. This study was approved by the institutional review board at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and all participants provided written informed consent to participate. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Neurocognitive testing

Neuropsychological testing was conducted within one day of brain imaging by a certified psychological examiner under the general supervision of a board-certified neuropsychologist. Primary neurocognitive functions assessed included intelligence (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence21), academics (Woodcock-Johnson III test of Achievement22), attention (Trail Making Test Part A23; Conners’ Continuous Performance Test-II24; Digit Span Forward from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III25), memory (California Verbal Learning Test-II26), processing speed (Grooved Pegboard27; Stroop Color Word Test28), and executive function (Trail Making Test part B23; controlled Oral Word Test; and Digit Span Backward25). Raw scores were transformed into age-adjusted z-scores based on population normative data. The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF)29 was used to assess self-reported problems with inhibition, cognitive flexibility, emotional control, self-initiation, working memory, planning and organization, self-monitoring and organization of materials. BRIEF scores were reported as T-scores (μ = 50, σ = 10) based on reference to age and sex normative data.

Image analysis

All imaging was obtained on a clinical 3 T MR scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA) and included a 3D T1-weighted MRI using sagittal 3D MPRAGE (magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo) sequence (TR/TE/TI = 1980/2.32/1100 ms) with an isotropic imaging resolution of 1.0 mm3. Axial susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) sequences were obtained (TR 56 ms, TE 25 ms, Flip Angle 20°, slice thickness 2 mm, 0.55 mm in plane resolution) with reconstruction of phase and amplitude images performed on the scanner using Siemen’s Syngo SWI processing software.

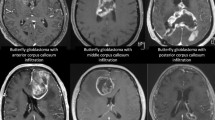

Region of interest (ROI) selection was performed using an in-house developed program written in MATLAB (Math Works, Natick, MA). Two trained reviewers (NSP and JY) independently selected hypointense foci that were not contiguous with perpendicular blood vessels, flow voids or consistent with mineralization (calcification). During this analysis, small focal intracerebral hemorrhages only visible on susceptibility sensitive MRI sequences (cerebral microbleeds) and Zabramski cavernoma classification Type IV malformations were not differentiated as they are radiographically indistinguishable at 3 T and both are associated with radiation related small vessel abnormalities30,31. Selection of microbleeds was confirmed by a board certified neuroradiologist. All coding was conducted without knowledge of treatment exposure or neurocognitive function.

Each microbleed was segmented using a 2D recursive region growing algorithm from a seed indicated by an experienced observer (Fig. 1). The connected 2D segments were combined to generate a 3D segmentation of the microbleeds. For each microbleed, the location of the center of mass and size in voxels and mm’s was recorded, as well as the microbleed count for each individual survivor. The coordinates for the center of mass of each microbleed were transformed into a standard brain reference space (MNI space) by first normalizing the SWI data set into template space using Statistical Parametric Mapping v12 (SPM 12)32. The resulting transformation was then applied to the coordinates of the center of mass. The coordinates were then mapped to Talirach space using the icbm2tal transform technique as previously described33. Location labels were generated for each microbleed based on the coordinates of the center of mass using the taxonomy maps developed by Brainmap.org.34,35. Microbleeds were assigned to one of the following locations: frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, occipital lobe, anterior lobe cerebellum, posterior lobe cerebellum, medulla oblongata, pons, sub-lobar (region defined to fill the remainder of volume within the hemisphere, such as the insular cortex) and midbrain. Locations were combined for left and right side. Additionally, microbleeds were categorized as located in grey matter or white matter, unless in the sub-lobar and brainstem regions where they were classified as mixed.

Example of a region of interest selection performed by the region filling algorithm. The arrow highlights the same microbleed in both the Susceptibility Weighted Minimum Intensity Projection image (SW mIP) (A,C) and corresponding Filtered Phase image. (B,D) Note detection and measurements could be accurately captured near areas of air induced susceptibility artifacts (orange arrow) using this method. (C,D) (Images are displayed in radiological convention).

Statistical analysis

Microbleeds were analyzed in two ways: presence of microbleeds for each brain region and cumulative microbleed counts (6 or more, top tertile vs other tertiles) due to a skewed distribution. Univariate analysis was conducted to identify neurocognitive scores significantly below the population mean (µ = 0, σ = 1.0) with those scores passing false discovery rate (FDR) correction selected for subsequent analysis. Multivariable modified Poisson regression was conducted to evaluate the effect of cranial radiation dose group (≥20 Gy vs <20 Gy) on the presence of microbleeds in selected brain regions, and multivariable linear regression was used to assess the effect of microbleeds (location and cumulative count) on neurocognitive outcomes without adjusting for multiple comparisons. All multivariable analyses were adjusted for age at diagnosis and sex. To further explore the effect of microbleed count on neurocognition, exploratory univariate analyses were conducted to compare the neurocognitive Z-scores between the 15 survivors who had no microbleed and the 15 people with 10 or more microbleeds. Additional exploratory analyses were conducted to evaluate if hypertension (a potential confounder) or methotrexate was associated with cumulative count of microbleeds. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Data availability

The data and code that supports this research study are available from the corresponding author upon request. All data used in this study is available upon request. Please contact Kevin.Krull@stjude.org.

References

Mulhern, R. K., Fairclough, D. & Ochs, J. A prospective comparison of neuropsychologic performance of children surviving leukemia who received 18-Gy, 24-Gy, or no cranial irradiation. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 9, 1348–1356, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1991.9.8.1348 (1991).

Spiegler, B. J., Bouffet, E., Greenberg, M. L., Rutka, J. T. & Mabbott, D. J. Change in neurocognitive functioning after treatment with cranial radiation in childhood. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 22, 706–713, https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.05.186 (2004).

Krull, K. R. et al. Neurocognitive outcomes decades after treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the St Jude lifetime cohort study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 31, 4407–4415, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.48.2315 (2013).

Koike, S. et al. Asymptomatic radiation-induced telangiectasia in children after cranial irradiation: frequency, latency, and dose relation. Radiology 230, 93–99, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2301021143 (2004).

Greene-Schloesser, D. et al. Radiation-induced brain injury: A review. Front Oncol 2, 73, https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2012.00073 (2012).

Edelmann, M. N. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and neurocognition in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Brain 137, 2973–2983, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu230 (2014).

Akoudad, S. et al. Cerebral Microbleeds Are Associated With an Increased Risk of Stroke: The Rotterdam Study. Circulation 132, 509–516, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016261 (2015).

Barnaure, I. et al. Clinicoradiologic Correlations of Cerebral Microbleeds in Advanced Age. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38, 39–45, https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4956 (2017).

Chan, M. S., Roebuck, D. J., Yuen, M. P., Li, C. K. & Chan, Y. L. MR imaging of the brain in patients cured of acute lymphoblastic leukemia–the value of gradient echo imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 27, 548–552 (2006).

Roddy, E. et al. Presence of cerebral microbleeds is associated with worse executive function in pediatric brain tumor survivors. Neuro Oncol 18, 1548–1558, https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/now163 (2016).

Chung, C. P. et al. Strictly Lobar Cerebral Microbleeds Are Associated With Cognitive Impairment. Stroke 47, 2497–2502, https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014166 (2016).

Faraci, M. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in childhood leukemia survivors treated with cranial radiotherapy: a cross sectional, single center study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57, 240–246, https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22923 (2011).

Haacke, E. M., Xu, Y., Cheng, Y. C. & Reichenbach, J. R. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI). Magn Reson Med 52, 612–618, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.20198 (2004).

Neu, M. A. et al. Susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of cerebrovascular sequelae after radiotherapy for pediatric brain tumors. Radiother Oncol 127, 280–286, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2018.03.010 (2018).

Morrison, M. A. et al. Risk factors of radiotherapy-induced cerebral microbleeds and serial analysis of their size compared with white matter changes: A 7T MRI study in 113 adult patients with brain tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26651 (2019).

Larson, J. J., Ball, W. S., Bove, K. E., Crone, K. R. & Tew, J. M. Jr. Formation of intracerebral cavernous malformations after radiation treatment for central nervous system neoplasia in children. J Neurosurg 88, 51–56, https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1998.88.1.0051 (1998).

Heckl, S., Aschoff, A. & Kunze, S. Radiation-induced cavernous hemangiomas of the brain: a late effect predominantly in children. Cancer 94, 3285–3291, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10596 (2002).

Shams, S. et al. SWI or T2*: which MRI sequence to use in the detection of cerebral microbleeds? The Karolinska Imaging Dementia Study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 36, 1089–1095, https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4248 (2015).

Trimble, M. Body image and the parietal lobes. CNS Spectr 12, 540–544 (2007).

Haacke, E. M., Mittal, S., Wu, Z., Neelavalli, J. & Cheng, Y. C. Susceptibility-weighted imaging: technical aspects and clinical applications, part 1. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 30, 19–30, https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A1400 (2009).

Wechsler, D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-second edition, Manual. (Pearson, 2011).

Woodcock, R. W., McGrew, K. S. & Mather, N. Woodcock-Johnson III tests of achievement. (Riverside Pub., 2001).

Reitan, R. M. T M Test, Manual. (Reitan Neuropyschology Laboratory, 1992).

Conners, C. K. The Computerized Continuous Performance-Test. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 21, 891–892 (1985).

Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale -third edition, Manual. (NCS Pearson, 1997).

Delis, D. C., Kramer, J. H., Kaplan, E., &Ober, B. A. California Verbal Learning Test -second edition. Adult Version Manual. (Psychological Corporation, 2000).

Merker, B. & Podell, K. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology (eds Jeffrey S. Kreutzer, John DeLuca, & Bruce Caplan) 1176–1178 (Springer New York, 2011).

Stroop, J. R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions, George Peabody College for Teachers (1935).

Gloia, G. A., Isquith, P.K., Guy, S.C. & Kenworthy, L. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function- second edition, Manual. (PAR inc., 2015).

Passos, J. et al. Microbleeds and cavernomas after radiotherapy for paediatric primary brain tumours. J Neurol Sci 372, 413–416, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2016.11.005 (2017).

Zabramski, J. M. et al. The natural history of familial cavernous malformations: results of an ongoing study. J Neurosurg 80, 422–432, https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1994.80.3.0422 (1994).

Penny, W. D., Friston, K. J., Ashburner, J. T., Kiebel, S. J. & Nichols, T. E. Statistical parametric mapping: the analysis of functional brain images. (Elsevier, 2011).

Lancaster, J. L. et al. Bias between MNI and Talairach coordinates analyzed using the ICBM-152 brain template. Hum Brain Mapp 28, 1194–1205, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20345 (2007).

Fox, P. T. & Lancaster, J. L. Opinion: Mapping context and content: the BrainMap model. Nat Rev Neurosci 3, 319–321, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn789 (2002).

Fox, P. T. et al. BrainMap taxonomy of experimental design: description and evaluation. Hum Brain Mapp 25, 185–198, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20141 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the St. Jude childhood cancer survivors and their families for their participation in this study. This study was supported (in part) by funding from the Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant (CA21765) to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (PI: Charles W. Roberts), National Cancer Institute grant U01 CA16647 (PI’s: Hudson and Robison), and R21 CA138998 (PI: Armstrong) and the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This cross-sectional study was developed by the principal investigator (N.D.S.) in collaboration with the lead investigator (N.S.P.). Data preparation was conducted by N.S.P., B.G.M., M.A.S. and C.M.H. Neuroimaging analysis was conducted by N.S.P., J.Y., and N.D.S. Statistical analysis was conducted by C.L. under the supervision of D.S. The manuscript was prepared by N.S.P., N.D.S. and K.R.K. and authors, T.E.M., G.T.A., C.H.P., L.L.R. and M.M.H. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript for submission. J.Y., M.A.S., B.G.M., and K.R.K. had access to the raw data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Phillips, N.S., Hillenbrand, C.M., Mitrea, B.G. et al. Cerebral microbleeds in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with cranial radiation. Sci Rep 10, 692 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57682-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57682-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.