Abstract

PdCl3 belongs to a novel class of Dirac materials with Dirac spin-gapless semiconducting characteristics. In this paper based, on first-principles calculations, we have systematically investigated the effect of adatom adsorption, vacancy defects, electric field, strain, edge states and layer thickness on the electronic and magnetic properties of PdCl3 (palladium trichloride). Our results show that when spin-orbital coupling is included, PdCl3 exhibits the quantum anomalous Hall effect with a non-trivial band gap of 24 meV. With increasing number of layers, from monolayer to bulk, a transition occurs from a Dirac half-metal to a ferromagnetic metal. On application of a perpendicular electrical field to bilayer PdCl3, we find that the energy band gap decreases with increasing field. Uniaxial and biaxial strain, significantly modifies the electronic structure depending on the strain type and magnitude. Adsorption of adatom and topological defects have a dramatic effect on the electronic and magnetic properties of PdCl3. In particular, the structure can become a metal (Na), half-metal (Be, Ca, Al, Ti, V, Cr, Fe and Cu with, respective, 0.72, 9.71, 7.14, 6.90, 9.71, 4.33 and 9.5 μB magnetic moments), ferromagnetic-metal (Sc, Mn and Co with 4.55, 7.93 and 2.0 μB), spin-glass semiconductor (Mg, Ni with 3.30 and 8.63 μB), and dilute-magnetic semiconductor (Li, K and Zn with 9.0, 9.0 and 5.80 μB magnetic moment, respectively). Single Pd and double Pd + Cl vacancies in PdCl3 display dilute-magnetic semiconductor characteristics, while with a single Cl vacancy, the material becomes a half-metal. The calculated optical properties of PdCl3 suggest it could be a good candidate for microelectronic and optoelectronics devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last few years two-dimensional materials (2DM) have been attracting enormous attention because they are considered potential candidates for future applications. The prospect of the Dirac half-metal (DHM) and the alternative of the quantum anomalous Hall effect (QAHE) without external fields is a great challenge due to the structural complexities of the 2D honeycomb lattice. A significant obstacle for practical applications of the QAHE is the lack of suitable QAH materials with a large non-trivial band gap, magnetic order and high carrier mobility. Half-metallicity, together with a wide half-metallic band gap and unusual ferromagnetic character have become a key driving force to develop next-generation spintronic devices. In 2DM, the spin of electrons provide an additional degree of freedom to tune their electronic and magnetic properties1. Quantum anomalous Hall insulators (Chern insulators, i.e. a quantized version of QAH2) are a novel topological phase of matter characterized by a finite Chern number and helical edge electron states within the bulk band gap3,4. Without an external magnetic field, and in the presence of magnetic interactions including ferromagnetic (FM) and antiferromagnetic (AFM) order, time-reversal symmetry (TRS) is broken while opening a non-trivial spin-orbital coupling (SOC) induced gap, giving rise to a quantized anomalous Hall conductivity5,6. For the first time, the idea of quantized Hall conductance without Landau levels on a honeycomb lattice was introduced by Haldane7. Exhibiting the QAHE, in the 2D honeycomb lattice is suggested as the first ingredient8,9.

Recently, a variety of QAH materials based on 2D honeycomb lattices of group IV materials including silicene, germanene, and stanene, have been predicted which possess a relatively strong intrinsic SOC, by introducing an exchange interaction via magnetic adatoms and surface functionalization10,11. Also 2DM based on the addition of adatoms and impurities12,13,14,15, or chemical decorations8,12 of graphene-like and Bi-based materials, and also in metal organic-frameworks16,17, interface and heterostructure materials18,19,20,21,22,23,24, it is predicted that the QAHE could be present. Too weak electronic correlations is an important problem in these 2DM in order to drive magnetism and to break TRS. Although, 2D Kagome lattices could potentially exhibit the QAHE, the nontrivial band gaps of these materials are too small and impede the observation of QAHE17,25,26.

Spin-gapless semiconductors (SGS), exhibiting a band gap in one of the spin channels and a zero band gap in the other, have received considerable recent attention due to their unique electronic properties and potential applications in novel spintronic devices27. The DHMs are based on a combination of single-spin massless Dirac fermions and half-semimetals with broken TRS. Only a few 2DM such as YN2, C7N6, VCl3 and NiCl328,29,30,31 show DHM characteristics.

Such materials are particularly suitable for utilization of their electronic spin degrees in nanoelectronic devices32,33,34,35. Accounting for SOC, the gap opening may trigger a QAH insulator transition in one spin channel only, which has been predicted for a few materials. The search for a new member of the Dirac SGS family with the QAHE is of great importance for both fundamental interest and practical applications. Also, QSHE has been reported in previously studies25,36. The layered crystals of transition-metal trichloride, and the family of layered materials with the general formula TMX3 (TM = Ti, V, Cr, Fe, Mo, Ru, Rh, Ir) and X is a halogen anion (X = Cl, Br, I) have become of interest for this purpose. In these structures, the transition-metal atoms are uniformly distributed in a honeycomb structure and the electronic and magnetic properties exhibit unusual features30,37,38,39 that have potential to be exploited in spintronic applications. These structures have been investigated for many years, before the present focus on layered materials40. Due to the weak interlayer van der Waals interactions, 2DM can be easily exfoliated from the corresponding 3DM by applying different technologies41.

Despite the fact that two-dimensional materials (2DM) hold great potential for a wide range of applications, it will be necessary to modulate their intrinsic properties. Several approaches have been developed to modify the electronic properties of 2DM. These methods involve substitutional doping, defect engineering, surface functionalization with adatoms, application of an electric field or strain, and by affecting the edge states. Many efforts have been put forth on the electronic properties and modification via these ways42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56. For example, with regard to achieving long-range magnetism in 2D systems, in ref. 43 semi (half) hydrogenated silicene was predicted to be a room-temperature ferromagnetic material, while ref. 48 reported a new two-dimensional honeycomb-Kagome structure which is predicted to possess the coexistence of spin-polarized multiple Dirac cones and nodal rings, with an estimated Curie temperature of 204 K. Also, Zhang et al.45 predicted from first-principles calculations that 2D SnHN and SnOH lattices possess the desirable combination of a sizeable nontrivial band-gap, high Curie temperature, and high carrier mobility. In this paper, based on first principles calculations, we investigate the electronic and magnetic properties of PdCl3, as an ideal candidate material for realizing both DHM and QAHE. When the SOC effect is included, a band gap opening occurs in one spin channel, which would lead towards the QAHE and PdCl3 becomes a Chern insulator due to TRS breaking. The physical origin of this QAH effect is due to both the intrinsic SOC and ferro-magnetism of the PdCl3. We comprehensively investigate the effect of layer thickness, electrical field and strain on the atomic and electronic structure of PdCl3. The results show that as the number of layers of PdCl3 is increased from monolayer to bulk, an electronic transition occurs from Dirac half-metal (monolayer) to ferromagnetic metal (quadlayer). A perpendicular electric field on the PdCl3 bilayer decreases the band gap. Upon uniaxial and biaxial strains, the variation in the electronic structure of PdCl3 can be controlled depending on the type and magnitude of the strain. The transition of electronic states in PdCl3 through layer thickness and electric field modulation, could shed light on the tailoring of such materials for the future development of nanoelectronic devices. Adsorption of adatoms and vacancy defects are able to further modify the electronic and magnetic properties of PdCl3. While pristine PdCl3 is a DHM, with adsorption of Al, Li, Na, K, Be, Mg, Ca, Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn adatoms, it can be turned into a metal, half-metal, ferromagnetic-metal, spin-glass semiconductor and dilute-magnetic semiconductor.

Method

In this work we perform total energy and electronic structure calculations using density functional theory within the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (GGA-PBE)57 for the exchange-correlation functional. We use norm-conserving pseudopotentials58 for Pd and Cl and the other adatoms. The wave functions are expanded in a linear combination of multiple pseudoatomic orbitals (LCPAOs) generated using a confinement scheme59,60. The k-points for sampling over the Brillouin zone (BZ) integration are generated using the Monkhorst-Pack scheme61 where a k-point mesh of 17 × 17 × 1 for the primitive unit cell is used. After convergence tests in OpenMX, we choose an energy cutoff of 400 Ry, so that the total-energy converges to below 1.0 meV/atom. The geometries are fully relaxed until the force acting on each atom is less than 1 meV/Å. The PdCl3 structures are modeled as a periodic slab with a sufficiently large vacuum layer of 22 Å in order to avoid interaction between adjacent layers. In order to accurately describe the vdW interaction in the few-layer PdCl3 systems, we adopted the empirical correction method presented by Grimme (DFT-D2)62 which has been demonstrated as reliable for describing the long-range vdW interactions. Electron charge transfer is calculated using the Mulliken charge analysis63. We perform full structural optimizations, where all atoms are relaxed in all directions and calculations are carried out using 2 × 2 × 1 supercell of PdCl3, which contains 32 atoms (8 Pd and 24 Cl atoms). Simulated scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) images are obtained using the Tersoff-Hamann theory64, as implemented in the OpenMX code and are graphed using the WSxM software65.

Additionally, we calculate the optical properties, including dielectric function, absorption coefficient, reflectivity, refractive index and extinction coefficient of PdCl3 using SIESTA66. The exchange-correlation functional is also taken as the GGA-PBE. Core electrons are replaced by norm-conserving, nonlocal Trouiller-Martins pseudopotentials58. A 400 Ry mesh cut-off is chosen and self-consistent calculations are performed with a mixing parameter of 0.1. The convergence criterion for the density matrix is taken as 10−4 Ry.

Pristine PdCl3

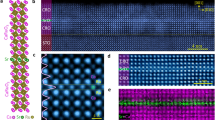

The structure of the PdCl3 monolayer with the space group P3m1 consists of a trilayer Cl-Pd-Cl (a sheet of Pd atoms sandwiched between two sheets of Cl atoms). The Pd atoms form a 2D honeycomb lattice and each Pd atom is bonded to six Cl atoms in an octahedral environment (see Fig. 1(a)). The optimized lattice constant of PdCl3 is 6.50 Å. The bond lengths of Pd-Pd and Pd-Cl are, respectively, 3.81 and 2.48 Å, while the vertical distance between the two Cl atomic planes is 3.59 Å. In an earlier work67, DFT calculations were performed where it was reported that the ground state is a 100% spin-polarized DHM with a ferromagnetic Curie temperature of 528 K as predicted from Monte Carlo simulations. Including spinorbit coupling revealed the QAHE due to the splitting of the manifold of Pd d-states near the Fermi level. This study furthermore reported the dynamical stability of this structure through calculation of the phonon modes, and demonstrated the absence of imaginary modes. Thermal stability was also checked by using molecular dynamics simulations67.

(a) Optimized atomic structures of the PdCl3 nanosheet, with its hexagonal primitive unit cell indicated by a red parallelogram. The gray (green) balls are Pd (Cl) atoms. Total, difference charge density and the difference spin density distributions are indicated in the same panel. The blue and yellow regions show, respectively, the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin states. (b) Simulated STM image. The STM images is overlayed with the PdCl3 structure. (c) Band structure and corresponding DOS and PDOS. The charge densities of the VBM and CBM are indicated in the inset. (d) Intensity map of electronic band structure. The zero of energy is set at \({E}_{F}\).

In Fig. 1(a) we show the total and difference electron charge densities. A high charge density can be seen around the Cl atoms, reflecting the electronegative character. The Pauling electro-negativity values for Pd and Cl atoms are 2.2 and 3.16, respectively. This electro-negativity difference explains the electron transfer from Pd atoms to Cl atoms. According to the Mulliken charge analysis, each Pd atom in PdCl3 loses 0.53 electrons. The calculated STM image of PdCl3 is shown in Fig. 1(b). To produce the calculated image, the Kohn-Sham charge density is integrated to 2 eV below EF. In Fig. 1(b) the inset structure represents the PdCl3 repeating unit cell. We see that the Cl atom in one sublayer exhibits a brighter spot than another sublayer.

In order to explain the electronic states of PdCl3 and clarify contributions from different orbitals, we have calculated the electronic band structure and corresponding density of states (DOS) and projected PDOS, as shown in Fig. 1(c,d). The \(\downarrow \) spin channel of PdCl3 is an indirect semiconductor and possess a 1.12 eV band gap, where the valence band maximum (VBM) and the conduction band minimum (CBM) are located at M and \(\Gamma \) points, respectively. The VBM of the \(\uparrow \) spin channel shifts down and crosses the EF and exhibits a gapless semiconductor character with a linear band dispersion relation near EF. The massless Dirac fermions are found in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel of PdCl3 at the high-symmetry K point of the Brillouin zone, where they are DHM with 100% spin polarization. Our result is in good agreement with previous calculations67. The electronic structure of PdCl3, exhibits a rather rare Dirac spin-gapless semiconductor character and unlike conventional Dirac-cone structures, here an excited Dirac fermion can be fully spin polarized (see Fig. 1(c)). From the PDOS of PdCl3, we see that the metallic state in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel at EF is dominated by Pd-\({d}_{xy,yz}\) and Cl-\({p}_{z}\) orbitals. The VBM of the \(\downarrow \) spin channel originates from Pd-(\({d}_{xz,yz}\)/\({d}_{{z}^{2},{x}^{2}{y}^{2}}\)) and Cl-\({p}_{y}\) states, while the CBM is derived from Pd-(\({d}_{xz,yz}\)/\({d}_{{x}^{2}{y}^{2}}\)) and Cl-\({p}_{z}\) orbital states (see Fig. 1(c)). The intensity map of the electronic band structure is shown in Fig. 1(d).

Dirac states in Dirac materials, including the IV-based 2D honeycomb lattice, are characterized by being composed of \(p\)-orbital states with weak SOC. While the Dirac states of PdCl3 mainly originate from the Pd-d orbitals and upon the inclusion of SOC, despite the fact that Dirac-cone feature is preserved, a nontrivial energy band gap opens in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel and TRS in the edge states is broken. The orbital-projected electronic band structure of PdCl3, on Pd and Cl atoms without spin-orbital coupling (SOC) and with SOC, are shown in Fig. 2(a,b). The states originate from \({E}_{2}\) (\({d}_{xy}\), \({d}_{{x}^{2}{y}^{2}}\)) with only a small contribution from the \({E}_{1}\) (\({d}_{xz}\), \({d}_{yz}\)) orbitals. Both the VB and CB exhibit equivalent weights of \({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\) orbital states, in calculations without SOC. With SOC, there are significantly increased contributions of both \({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\) in the CB while the \({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\) contributions to the VB decrease, resulting in the degeneracy of the \({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\) orbitals around the Dirac-point being lifted, opening thus a global energy gap between the CB and VB energies. Consequently, the \({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\) orbitals play a prominent role in the electronic topological properties of PdCl3. The larger SOC gap of Pd-d orbitals with broken TRS may lead to the Chern insulator and the QAH effect. The band gap is calculated to be 20 meV (with SOC) and 24 meV (with SOC + U) which is sufficiently large for the QAH effect to be observable.

Orbital-projected electronic band structure of PdCl3 (a) without SOC and (b) on an enlarged scale with and without SOC (for the spin-up channel), (c) The schematic of crystal field and exchange splitting for Pd ions. (d) The PDOS of \(d\) orbital states for Pd atoms is shown. The difference spin density distribution is shown as the inset. The blue and yellow regions represent the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin states. The zero of energy is set at \({E}_{F}\).

To understand the origin of the magnetic moment in PdCl3, we investigate the crystal symmetry of the Pd-4d orbital states (see Fig. 2(c)). In PdCl3, each Pd atom is coordinated by six Cl atoms, forming a distorted octahedral crystal field. Also the Pd-4d orbital states split into three \({t}_{2g}\) (\({d}_{xy,{x}^{2}{y}^{2}}\)) and two \({e}_{g}\) (\({d}_{xz,yz}\)) orbital sub-states in a perfect octahedral crystal field. Due to the \({D}_{3d}\) point-group symmetry, structural distortion of the PdCl6 octahedron makes the \({t}_{2g}\) state further split into the \({A}_{1}\) (\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\)) and doubly-degenerate \({E}_{2}\) states, while they are still energetically lower than that of the \({E}_{1}\) states. Under an exchange field, Eex, as introduced by internal magnetism, the degeneracy of the \({A}_{1}\), \({E}_{2}\) and \({E}_{1}\) orbital states split significantly due to Hunds coupling. For a Pd+3 state, six electrons with both \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin channels fully occupy the \({A}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\) states, while only one electron is left in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel of \({E}_{1}\), resulting in an integer magnetic moment.

To gain insight into the origin of its electronic, magnetic and topological properties, the PDOS of PdCl3 is shown in Fig. 2(d). We see that the Pd-d orbital states would be split into \({E}_{1}\), \({E}_{2}\) and \({A}_{1}\) states under the distorted octahedral crystal field of Cl atoms. In an octahedral crystal field PdCl3, based on Griffiths crystal field theory, the spin states of the TM ions can be determined by the relative strength between crystal field splitting (Δ\({E}_{cf}\)) and Hund-exchange splitting (Δ\({E}_{ex}\)) of Pd-d orbitals. The relative strength of the crystal field splitting is calculated ΔEcf = 1.02 eV, that is, larger than ΔEex = 0.8 eV, resulting in a low spin (1 μB) state which is in agreement with the Pd (\({d}^{\uparrow 4}\downarrow 3\)) spin configuration. The states around \({E}_{F}\) mainly originate from \({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\) orbitals, while the \({A}_{1}\) orbital does not contribute significantly. The partially occupied \({E}_{1}\) and \({E}_{2}\) orbitals around the \({E}_{F}\) form a Dirac-point in PdCl3.

Magnetic order

In the following, we study the lowest energy structures of PdCl3 for different spin orientations, including nonmagnetic (NM), ferromagnetic (FM) and anti-ferromagnetic AFM) order. The electronic band structure of NM, FM and AFM orders are shown in Fig. S1(a–c). Clearly, the NM order exhibits a zero band gap due to the lowest \({t}_{2g}\) orbitals being half-filled with a 4d8 electronic configuration for the Pd+3 ions, leading to a metallic state. We find a Dirac-point in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel of the FM state, up to \({E}_{F}\). In the case of AFM order, we find that the states shift to higher energy and peaks sharpen as compared to the FM order, and the system exhibits metallic character. In the AFM order, it can be seen that the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin channels around \({E}_{F}\) almost overlap and do not show a Dirac-point. In the case of the FM state the magnetic moment is 2 μB per unit cell. The semiconducting energy band gap in the \(\downarrow \) spin channel is 1.63 eV. A comparison of total energies for the ferromagnetic (FM), non-magnetic (NM), and antiferromagnetic (AFM) configurations show the lowest energy configuration to be FM for PdCl3. These results indicate that the magnetic ordering has important implications on the electronic band structures, especially at the band edges.

Hubbard U

Due to the weak screening of the Coulomb interaction in 2DM, it is expected that the Hubbard U will be larger than in three-dimensional materials, thus the energy band gap may be expected to be enhanced significantly. We investigate effects of correlation by varying the value of the Hubbard U. The electronic band structure and PDOS of PdCl3 calculated for various values of U are shown in Figs. S2 and S3. The DOS of PdCl3 without SOC, as a function of the Hubbard U, is shown in Fig. S2(a) and the PDOS of the Pd atom d states is shown in Fig. S2(b). The correlation effects on the electronic and magnetic properties of PdCl3 are significant and cause changes in the spin polarization of PdCl3. We see from the PDOS that the PdCl3 structure still maintains the DHM feature even when considering the effect of the Hubbard U, and the magnetic moment is essentially unchanged (1.99 μB for U = 0.5 eV and is 2 μB for U = 4 eV). With increase of Hubbard U, the \({d}_{xz}\) and \({d}_{yz}\) orbital states do not change near \({E}_{F}\), indicating the robustness of nontrivial topology against the correlation effect in Pd-4d electrons. The electronic band structure of PdCl3 with SOC as a function of Hubbard U, is shown in Fig. S3(b). The band gap opening is a result of a cooperative effect of electron correlation with SOC. Our results show that the band gap of PdCl3 increases from 20 meV for U = 0.5 eV to 45 meV for U = 4 eV, and therefore QAHE remains for U = 4 eV. This trend is similar to that of ref. 67 which reported that the band gap varies from around 25 meV to 68 meV for values of U from 1.0 to 4.0 eV. This study furthermore reported a band gap of 63 meV as obtained from DFT calculations with the HSE06 hybrid functional.

Layer thickness

In order to understand the effect of layer thickness on the electronic properties, we perform band structure calculations for different thicknesses of PdCl3 (2L, 3L and 4L). The optimized structures and electronic band structure of 2L to 4L-PdCl3, are illustrated in Fig. 3(a–c), respectively. After geometry optimization and energy minimization, the interlayer distances between the layers of PdCl3 in the sandwich structures were obtained in the range of 2.548–2.582 Å. Moreover, for a few layer PdCl3, the bond length of Pd-Pd is in the range of 3.790–3.844 and Pd-Cl 2.458–2.533 Å. We find that the bond lengths increase compared to that of the PdCl3 monolayer (bond lengths of Pd-Pd and Pd-Cl in 1L-PdCl3 are 3.811 and 2.480 Å, respectively). Our results show that more than one layer of PdCl3, the electronic states are modified. In particular, 2L-PdCl3, exhibits half-metal behavior, namely the \(\uparrow \) spin channel is an indirect semiconductor with a small band gap of 70 meV, where the touches \({E}_{F}\) and becomes gapless. The VBM and CBM of the \(\uparrow \) spin channel are located at the \(\Gamma \) and K points, respectively. The 2L-PdCl3 has 0.6 μB magnetic moment. We can see that the 3L-PdCl3 becomes a ferromagnetic-metal and has magnetic moment of 11 μB in the ground state;. 4L-PdCl3 also exhibits metallic character with a magnetic moment of 7 μB. Thus, as the number of layers increases from 1L to 4L for the PdCl3 structure, the electronic states indicate a transition from a Dirac half-metal (1L) to half-metal (2L), and to a ferromagnetic-metal (3L and 4L), whree the calculated thickness are: 1L (3.590), 2L (8.124), 3L (13.492 Å) and 4L (18.518 Å). The thickness of 2L-PdCl3 (~8.124 Å) appears to be the critical thickness for such a DHM to metal transition. The nature of the band gap change in PdCl3 can be explained by a combination of quantum confinement and vdW interlayer interactions.

Electric Field Effect On Bilayer PdCl3

In the following, we present the effect of an external uniform electric field on the electronic and magnetic properties of bilayer PdCl3 for two different spin configurations, namely, FM and AFM. The electric field is applied perpendicular to the plane of the PdCl3 bilayer. The schematic structure of the PdCl3 bilayer with two spin configurations under an electric field, is shown in Fig. 4(a). The \({{\rm{F}}}_{field} > 0\) denotes parallel to the z-axis and the value of electric field is considered between 0.2 and 1 V/Å. The band structures of PdCl3 bilayer in the FM and AFM configurations are shown in Fig. 4(b,c), respectively.

(a) Difference spin densities for the FM and AFM. The blue and yellow regions represent the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin states, respectively. Electronic band structure of the PdCl3 bilayer in the (b) FM and (c) AFM configurations for different values of the electric field. The zero of energy is set at \({E}_{F}\).

For the FM configuration, we found when the electric field increases from 0.2 to 1 V/Å, different electronic behaviour occurs including; dilute-magnetic semicounductor at 0.2, 0.6 and 1 V/Å with magnetic moment of 0.4, 0.35 and 0.2 μB; half-metal (at 0.4 V/Å) and ferromagnetic-metal (at 0.8 V/Å) with 3.9 μB and 3.7 μB magnetic moments, respectively. We can see that the modification in the band structure occurs in both \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin channels in the AFM configuration, and leads to a transition to ferromagnetic-metal at 0.2 and 0.4 V/Å with magnetic moments of 0.9 and 0.4 μB. While with incresing electic field to 0.6 V/Å and 1 V/Å, the PdCl3 bilayer becomes a dilute-magnetic semiconductor. The half-metallicity can be seen at 0.8 V/Å with 3.8 μB magnetic moment. As a result, it is possible to tune the electronic properties of PdCl3 bilayer and control the EF by applying an electric field. The existence of the layered structure in the PdCl3, gives rise to a potential difference between the two atomic sublayers, which turns out to provide an useful tuning of the electronic and magnetic properties by a perpendicular electric field. Owing to their tunable band gaps and magnetism over a wide range, the layered PdCl3 material may have tremendous opportunities for application in nanoscale electronic and optoelectronic devices.

Strain Effect

Strain engineering is an effective approach to tune the electronic properties and the topological nature of 2DM. Here, we investigate the effects of uniaxial and biaxial strain on PdCl3. The schematic structure of PdCl3 under uniaxial and biaxial strain, is shown in Fig. 5(a). Maintaining the crystal symmetry, the tensile and compression strain are defined as \(\varepsilon =(\tfrac{a-{a}_{0}}{{a}_{0}})\times 100\), where \(a\) and \({a}_{0}\) are strained and non-strained lattice constants, respectively. The positive and negative values denotes tensile and compression states, respectively. Uniaxial strain is applied along the zigzag directions, while biaxial strain is applied along the a-b axis. The variation of the structural parameters, including the Pd-Pd and Pd-Cl bond lengths, bond angles and lattice constant as function of strain, are shown in Fig. 5(b–e). We find that the bond lengths and lattice constant, under both uniaxial and biaxial tensile (compression) strain from 0 to +8% (to −8%) increase (decrease) monotonically as expected. The electronic band structure of PdCl3 under uniaxial and biaxial strains are obtained as shown in Fig. 5(e,f). Notice that the value of the nontrivial band gap is modified significantly and therefore the topological nature of PdCl3 can be tuned by applying uniaxial or biaxial strain. Variation of band gap in the \(\downarrow \) spin channel of PdCl3 as a function of uniaxial and biaxial strains, are shown in Fig. 5(h). For the \(\downarrow \) spin channel of PdCl3, the band gap decreases monotonically as uniaxial and biaxial tensile strains are increased. This situation is different for compressive strain. Under a compressive biaxial strain, from 0% to −8%, the band gap increases. In the case of the \(\uparrow \) spin channel (inset), the band gap is approximately invariant under biaxial strain from 0 to +8%, while from 0 to −6%, the band gap increases and becomes zero at −8%. For large uniaxial strain (>−6%), a DHM to HM transition is predicted to occur, while for biaxial compressive strain (>−8%), a DHM to dilute-magnetic semiconductor transition occurs. In contrast, under applied biaxial strain, the nontrivial topological states of PdCl3 are preserved.

(a) Lattice constant and (b–d) bond lengths and bond angles as function of strain. The schematic structure of PdCl3 under in-plane uniaxial and biaxial strain for both tensile and compressive strain is shown in the inset of (a). (e,f) Electronic band structures of PdCl3 as function of uniaxial and biaxial strains. (g) Variation of the band gap as function of uniaxial and biaxial strain for PdCl3. The zero of energy is set at \({E}_{F}\).

Vacancy Defects

In this section, we study effects of topological defects (including single and double vacancies) on the structural, electronic and magnetic properties of PdCl3. We remove Pd and Cl atoms to produce single vacancies of the Pd atom (\(S{V}_{Pd}\)) or Cl atom (\(S{V}_{Cl}\)), while for double vacancies, we remove both the Pd + Cl (\(D{V}_{PdCl}\)) atoms. The defective structures of PdCl3 are fully relaxed and accurate ground state energies and band structures are obtained. The optimized atomic structures of PdCl3 with vacancy defects are shown in Fig. 6. The bond length between Pd-Cl and Pd-Pd atoms in the vacancy structures is ~2.343 and 3.686 Å, respectively. We find that compared to pristine PdCl3 (Pd-Pd and Pd-Cl bond lengths are 3.811 and 2.480 Å) the bond lengths decrease around the vacancy defects. In order to better identify and investigate the effects of defects on PdCl3, difference charge densities and simulated STM images for different vacancies of PdCl3, are shown in Fig. S4. We see that the Cl atoms appear as white spots, however, the region around the vacancy defects corresponds to the brightest spot.

Optimized structures and electronic band structure with corresponding DOS and PDOS of PdCl3 with (a) a single Pd vacancy, (b) a single Cl vacancy and (c) the Pd + Cl double vacancy. The difference spin density distributions are shown in the insets. The blue and yellow regions represent the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin states, respectively. The zero of energy is set at \({E}_{F}\).

By performing spin-polarized calculations, we calculate the electronic and magnetic properties of PdCl3 in the presence of vacancy defects as shown in Fig. 6(a–c). We see that the \(S{V}_{Cl}\) exhibits a dilute-magnetic semiconductor character with direct band gaps of 75 meV and 0.34 eV in the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin channels, respectively (the VBM and CBM are located at the M point in both spin channels) and has a magnetic moment of 2 μB. It is also seen from the DOS and PDOS that the state at \({E}_{F}\) is due to the missing Pd atom, which confirms the semiconducting behavior of \(S{V}_{Pd}\) and also the magnetism is derived from these states. Unlike the \(S{V}_{Cl}\), the \(S{V}_{Pd}\) exhibits a half-metal character with a direct band gap of 0.72 eV, where the VBM and CBM are located at the \(\Gamma \) and M points, in the \(\downarrow \) spin channel. The \(\uparrow \) spin channel presents a metallic character with the electronic bands crossing \({E}_{F}\). A magnetic moment of 6.21 μB is induced due to the dangling bonds around the single vacancy and an unpaired electron. From the DOS and PDOS, we see that the state at \({E}_{F}\) originates from orbitals around the Pd atom, which gives rise to the metallic behavior of the \(S{V}_{Pd}\) in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel. Similarly to \(S{V}_{Cl}\), the \(D{V}_{PdCl}\) defect exhibits a dilute-magnetic semiconductor character with a direct band gap of 0.67 eV where the VBM and CBM are located at the \(\Gamma \) point, and there is an induced magnetic moment of 0.55 μB. To obtain further insight into the character of the bonding, the difference electron charge density distributions of defective PdCl3 are presented in Fig. S7. We can see that there is an obvious charge accumulation around the Cl vacancies. The difference in spin densities are presented in the same panel in Fig. 6(a–c).

Adsorption of Adatoms

In the following we investigate the adsorption of alkali metal (AM) including Li, Na, K and alkali earth metal (AEM) and Be, Mg, Ca and Al adatoms on PdCl3. The optimized structures, with corresponding difference charge densities, are shown in Fig. S5(a,b). The Li, Na, K, Mg, Ca and Al adatoms bond to the six Cl atoms of PdCl3 in the stable H-site and do not show any significant distortion. The dA–Cl of these adatoms is in the range of 2.314–3.029 Å. Of the adatoms, Be binds most strongly to PdCl3, and has the shortest bond length, dA–Cl = 2.314 Å, and the largest for K with dA–Cl = 3.029 Å. The height of the adatoms above the surface is calculated as the difference between the average coordinates of neighboring Cl atoms and the adatom, and is in the range of 1 Å. We see that the dPd–Cl bond lengths in the Ad/PdCl3 structures, are in the range of 2.516–2.697 Å, which compared to those in PdCl3 (Pd-Pd and Pd-Cl are 3.811 and 2.48 Å) the bond length of Pd-Cl is increased. These adatoms do not have a significant effect on altering the positions of the neighboring Cl atoms, and the deformation in the PdCl3 structure is negligible.

We calculated the adsorption energy is defined as \({E}_{a}={E}_{Ad/PdC{l}_{3}}\)-\({E}_{PdC{l}_{3}}\)-\({E}_{Ad}\), where \({E}_{Ad/PdC{l}_{3}}\) is the total energy of the structure with adatom adsorption on PdCl3, \({E}_{PdC{l}_{3}}\) is total energy of pristine PdCl3 without adatoms, and \({E}_{Ad}\) is the total energy of an isolated adatom in vacuum. We labeled adatom adsorbed on PdCl3 as Ad/PdCl3. The determined adsorption energies of Li, Na, K, Be, Mg Ca and Al atoms adsorbed on PdCl3 are 3.50, 2.75, 2.49, 4.10, 4.39, 5.12 and 5.51 eV, respectively. These values are all larger than the respective (experimental) cohesive energies (see Table S1 of the SI), indicating that formation of these structures is favourable compared to forming clusters on the surface. The difference charge densities of Ad/PdCl3 are shown in Fig. S5(b). We see that strong electron depletion occurs on the adatoms, while there is a local electron gain on the Cl hexagon, which demonstrates the largely ionic character of the Ad-Cl bonds.

The electronic band structures, corresponding DOS/PDOS of Ad/PdCl3 (Ad = Li, Na, K, Be, Mg, Ca and Al), and difference spin densities are given in Fig. 7(a–c). Compared to the band structure of pristine PdCl3, it can be seen that the adsorption bands of these adatoms mainly concentrate around \({E}_{F}\), which are formed by the hybridization between AM-s with Pd-\(d\) and Cl-\(p\) orbital states. We see from the band structure of Li and K/PdCl3, that the energy bands split into \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin channels, and so these adsorbate structures become dilute-magnetic semiconductor-like. After adsorption of Li and K atoms, the band structure exhibits a small direct band gap of respectively, 50 meV and 30 meV in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel, while the \(\downarrow \) spin channel has a band gap of 1 eV. The magnetic moment (per unit cell) for Li and K in the ground state is 9 μB, while the Na/PdCl3 system becomes a nonmagnetic metal. From the DOS and PDOS, it can be seen that for Na the metallic character (sharp peaks) near \({E}_{F}\) originate from the Cl-\(s\) and Na-\(s\) orbitals. The Be/PdCl3 system becomes a half-metal with an indirect band gap of 0.1 eV, where the VBM and CBM are located at the M and \(\Gamma \) points, respectively, and induces a magnetic moment of 0.72 μB.

The adsorption of Mg leads to a structure that exhibits a spin-glass semiconductor character, namely, the \(\uparrow \) spin channel is gapless, while the \(\downarrow \) spin channel is a direct semiconductor with a band gap of 100 meV and the VBM of the \(\downarrow \) spin channel touches the Fermi level. With adsorption of Mg, the degeneracy of both spin channels are broken and a magnetic moment of 3.3 μB is induced. For Ca and Al adsorption, impurity states appear in the vicinity of \({E}_{F}\), and exhibit metallic characteristics in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel, while in the down spin channel it exhibits semiconducting character with band gaps of 1 eV and 20 meV, respectively. The half-metallic character of the Ca and Al systems induces magnetic moments of 9.6 and 1.8 μB. From the DOS and PDOS, shown in Fig. 7(b), we see that the state at \({E}_{F}\) has Ca/Al-\(s\) orbital character which confirms the metallic behavior in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel. It can also be seen from the DOS and PDOS shown in Fig. 7(b), that the VBM of the Mg and Ca structures consists of \(s\) and \({p}_{y}\)-orbitals and the CBM consists of \({p}_{x,z}\)-orbitals, which confirms the semiconducting behavior of these structures. The difference spin density that is calculated from the charge density difference between the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin channels, are shown in Fig. 7(c).

The relaxed structures of the TMs/PdCl3 systems (TM = Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn adatoms) at the stable H-site, are shown in Fig. 8. We see that the TM adatoms, similarly to the AM, bind to the six Cl atoms of PdCl3. Unlike the AM and AEM adatoms however, which only weakly interact with the PdCl3 structure, adsorption energy of TMs adatoms on PdCl3, can result in a relatively stronger interaction between the TMs and PdCl3 and a smaller dAd–Cl distance. The bond length, dAd–Cl, of the TM adatoms is in the range of 2.281 (Co)–2.528 (Sc)Å. The height of adatoms is calculated as the difference between the average coordinates of neighboring Cl atoms and the adatom and is in the range of 1 Å. The dPd–Cl bond length in the Ad/PdCl3 structure, is in the range of 2.401–2.720 Å, which in comparison to PdCl3 (2.480 Å) is greater. The adsorption of TMs adatoms can result in relatively stronger interaction with values of 4.92, 5.23, 6.54, 6.97, 7.28, 7.29, 6.81, 4.92, 3.90 and 2.53 eV, respectively. Similarly to the AM and AEM adatom systems discussed above, all the adsorption energies of the TM are larger than the respective cohesive energies indicating the metal atoms will prefer to be bonded in the nanosheet compared to forming metal clusters on the surface (see Table S1 of the SI). Of the TM adatoms, Co and Sc have the largest and smallest bond lengths, respectively. We see that some of the adatoms, such as Co and Zn, exhibit a shifting of the position of the neighboring Cl atoms, resulting in a noticeable deformation in the PdCl3 structure. The difference charge densities of TMs/PdCl3, are also shown in Fig. 8. Considering, for example Cr/PdCl3, a charge accumulation appears in the region of the Cr atom and the neighboring Cl atoms, exhibiting a strongly covalent bonding character in the formed dCr–Cl bond. Such stronger covalent bonding is also found in most of the other TMs/PdCl3.

The electronic band structure of the TM/PdCl3 systems are shown in Fig. 9 and the DOS and PDOS in Fig. S6. The \(d\)- and 4\(s\)-orbitals of the TMs have similar energies, and the initial magnetic moment of the isolated TMs are nonzero unless the 3\(d\)-orbital shell is completely occupied. As the 3\(d\)-orbitals are located near to the nucleus, TMs with their partially occupied 3\(d\)-orbital shells can exhibit a diversity of electronic properties. The adsorbate’s Sc, Mn and Co, exhibit a ferromagnetic-metal character with induced magnetic moments of 4.55, 7.93 and 2.0 μB, respectively. The metallic state originates from the \(4s(\uparrow )\) and \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}(\downarrow )/3{d}_{xy}\) orbital states at \({E}_{F}\). With adsorption of Ti, V, Cr and Fe on PdCl3, the system remains metallic in the electron \(\uparrow \) spin channel, whereas the \(\downarrow \) spin channel bands exhibit semiconductor character, resulting in half-metal systems. The magnetic moments of Ti, V, Cr, Fe/PdCl3 are 7.14, 6.90, 9.71 and 4.33 μB, respectively. The Ti- and V-adsorbate systems have 0.1 eV and 5 meV indirect band gaps in the \(\downarrow \) spin channel, respectively. While the Cr- and Fe-adsorbate structures have indirect band gaps of 30 meV and 15 meV, respectively, in the \(\uparrow \) spin channel.

From the band structure in Fig. 9(b), we see that the Ni/PdCl3 structure becomes a spin-glass semiconductor with 50 meV and 100 eV indirect band gaps in the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin channels, respectively, with an induced magnetic moment of 8.63 μB. The Cu/PdCl3 structure has band gaps of 1 eV and 30 meV in the \(\uparrow \) and \(\downarrow \) spin channels, respectively. This structure in the ground state has a large magnetic moment of 9.5 μB. With adsorption of Zn on PdCl3, the structure becomes a dilute-magnetic semiconductor and induces a magnetic moment of 5.80 μB. The spin density differences of the TMs/PdCl3 systems are shown in Fig. S7. The charge carriers around EF are mobile, which is not only useful for conductive behavior but also for magnetic coupling. The difference spin density of Sc, Cu/PdCl3, show that the sign of spin density about the Sc and Cu adatoms and its six Cl atom neighbors are opposite, thus displaying a (weak) FM interaction between them. In other systems, we can observe highly localized opposite spin densities, thus indicating the presence of an AFM interaction in these doped structures.

Edge States

By cutting a PdCl3 nanosheet along the \(x\)- or \(y\)-directions we obtain a PdCl3 nanoribbon (PdCl3NR) with two types of edge configurations. Such ribbons exhibit a rich variation of electronic properties and characteristics due to its edge states, which depend on the width, which may provide important features for various technological applications. Two major families of PdCl3NRs are distinguished depending on their orientations, namely, armchair and zigzag PdCl3NRs. For the armchair edge states, the width, \(n\) is defined by the number of Pd-Cl chains in the unit cell which are parallel to the axis of the nanoribbon, while for the zigzag edge states, \(n\) denotes the number of zigzag Pd-Cl chains along the nanoribbon axis. For convenience, they are specified as \(n\)Z-PdCl3NR and PdCl3NR, respectively. In the present work, one type of PdCl3NR with zigzag edges is investigated. The schematic structure of the Z-PdCl3NR is show in Fig. 10 (inset). The electronic band structure and DOS of Z-PdCl3NR, is also shown in Fig. 10(a). The VBM or CBM are determined by edge states and quantum confinement effects, thus the electronic band structure is modified significantly as compare to the infinite sheet. The charge densities of the VBM and CBM are shown in Fig. 10(b). We find that the DHM characteristic of the PdCl3 nanosheet is transformed to that of a dilute-magnetic semiconductor with a magnetic moment of 6.0 μB.

Optical Properties

Since PdCl3 is a semiconductor in the \(\downarrow \) spin channel, it is important to investigate its optical manifestations. Here, we compute the optical properties using SIESTA, which are constructed from the orbital atomic functions converged by the PBE potential. In particular, we calculated the optical properties: the dielectric function, absorption coefficient, reflectivity, refractive index (\(n(\omega )\)) and extinction coefficient (\(K(\omega )\)) of PdCl3. The absorption coefficient is a percentage that tells the decay of light intensity spreads in unit distance in the medium as shown in Fig. 11(a). We see that the absorption coefficient is almost zero when the energy is in the range of 0.62–1.02 eV, and there is no electronic transition because the energy of the photon is lower than the band gap of PdCl3 (1.12 eV). Also, in the range of 5.62–7.47 eV (ultraviolet region), the absorption coefficient is zero. When the photon energy is larger than the value of the band gap, the absorption coefficient will increase. The absorption spectrum starts from about 4.773 × 104 at 0.34 eV, after which the intensity varies with increase in photon energy, and reaches a maximum value of 32.5 × 104 at 2.78 eV. A secondary peak is located at the value of 17.85 × 104 at 4.20 eV. The major peak appears in a broad energy range of 2.7–4.2 eV, which indicates the pronounced absorption of visible light (2.5–4.5 eV) in PdCl3. The refractive index and extinction coefficient, are presented in Fig. 11(b).

The static refractive index is calculate to be n(0) = 4.50 and the maximum frequency of \(n(\omega )\) is 2 at 2.16 eV. At high photon energy, the refractive index eventually tends to the value of one, while increases and decrease with energy in both the IR and Visible region. From \(K(\omega )\) the local maxima of the extinction coefficient corresponds to the zero of \({\varepsilon }_{1}(\omega )\) ~ 0.21 eV. The spectrum curve of \(n(\omega )\) and \(K(\omega )\) rapidly decreases with increasing photon energy in the UV region and it will becomes constant after 20 eV. The real (absorptive) parts of the optical conductivity of PdCl3 are shown in Fig. 11(c). We see that the peak absorption happens at the photon energy of 2.52 eV and reduces gradually to zero at the high energy region. The real (\({\varepsilon }_{1}(\omega )\)) and imaginary (\({\varepsilon }_{2}(\omega )\)) parts of the complex dielectric function, is shown in Fig. 11(d). The real part of the dielectric function gives information about the electronic polarizability of the material. We see that the static dielectric constant in the zero frequency limit is obtained as \({\varepsilon }_{1}(0)\) = 19. The quantity \({\varepsilon }_{1}(\omega )\) can become negative and this indicates that PdCl3 exhibits a metallic behavior in this frequency region. For \({\varepsilon }_{2}(\omega )\), there are mainly two peaks, which are 9.7 at 0.09 eV and 2.37 at 3.45 eV. In PdCl3, peaks in the real and imaginary part of the dielectric function are mainly due to electronic transitions from 4\(d\)-orbital in the valence band to 5\(s\)-orbital in the conduction band and there is also possible an electronic transition from 5\(s\)-orbital in the valence band to 5\(p\)-orbital in the conduction band. It is well known that materials with band gaps below 1.55 eV work well in the infrared (IR) and Visible region of the spectrum. Therefore PdCl3 will function in the IR and Visible region as an optical material.

Conclusion

In summary, by using first-principles calculations, we have systematically investigated the effects of adatom adsorption, vacancy defects, electric field, strain engineering, edge states and layer thickness on the structural, electronic and magnetic properties of the 2D honeycomb metal-halogen lattice, PdCl3 (paladium trichloride) monolayer. Our calculations show that PdCl3 is a Dirac half-metal (DHM) and exhibits a QAHE with a large non-trivial band gap of ~25 meV. We found that PdCl3 prefers a ferromagnetic spin orientation in the plane for Pd atoms with a 2 μB magnetic moment. The effect of correlation in the Pd-4\(d\) orbitals and SOC is investigated by including the on-site Coulomb repulsion U, We find that this results in an increase of the band gap (from 20 meV for U = 0.5 eV to 45 meV for U = 4 eV). Our results show that with increasing number of layers from monolayer to quadlayer, the electronic structure indicates a transition from Dirac half-metal (monolayer) to half-metal (bilayer) to a ferromagnetic metal (trilayer, quadlayer). Furthermore, when an electric field is applied perpendicular to the bilayer PdCl3, the band gap decreases, while under uniaxial and biaxial strain, the band structure can also be modified. With adsorption of adatoms, PdCl3 can be turned into a metal (Na), half-metal (Be, Ca, Al, Ti, V, Cr, Fe and Cu); ferromagnetic-metal (Sc, Mn and Co); spin-glass semiconductor (Mg, Ni); dilute-magnetic semiconductor (Li, K and Zn), while single (Pd, Cl) and divacancy defects (Pd + Cl) induce dilute semiconductor and metallic properties, respectively. Through these functionalization and bandstructure engineering approaches, the electronic properties and magnetism of PdCl3 nanosheets can be tuned.

References

Checkelsky, J. G. et al. Trajectory of the anomalous hall effect towards the quantized state in a ferromagnetic topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 10, 731 (2014).

Onoda, M. & Nagaosa, N. Quantized anomalous hall effect in two-dimensional ferromagnets: Quantum hall effect in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 206601 (2003).

Wu, J., Liu, J. & Liu, X.-J. Topological spin texture in a quantum anomalous hall insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 136403 (2014).

Qiao, Z. et al. Quantum anomalous hall effect in graphene proximity coupled to an antiferromagnetic insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 116404 (2014).

Halperin, B. I. Quantized hall conductance, current-carrying edge states, and the existence of extended states in a two-dimensional disordered potential. Phys. Rev. B 25, 2185–2190 (1982).

Zhou, P., Sun, C. Q. & Sun, L. Z. Two dimensional antiferromagnetic chern insulator: Nirucl6. Nano Lett. 16, 6325–6330 (2016).

Haldane, F. D. M. Model for a quantum hall effect without landau levels: Condensed-matter realization of the “parity anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015–2018 (1988).

Wu, S.-C., Shan, G. & Yan, B. Prediction of near-room-temperature quantum anomalous hall effect on honeycomb materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 256401 (2014).

Di, X., Wenguang, Z., Ying, R., Naoto, N. & Satoshi, O. Interface engineering of quantum hall effects in digital transition metal oxide heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 2, 596 (2011).

Xiao-Long, Z., Lan-Feng, L. & Wu-Ming, L. Quantum anomalous hall effect and tunable topological states in 3d transition metals doped silicene. Sci. Rep. 3, 2908 (2013).

Wang, X.-P. et al. Large-gap quantum spin hall state in functionalized dumbbell stanene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 073104 (2016).

Zhang, H., Lazo, H. C., Blügel, S., Heinze, S. & Mokrousov, Y. Electrically tunable quantum anomalous hall effect in graphene decorated by 5d transition-metal adatoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 056802 (2012).

Liu, J., Park, S. Y., Garrity, K. F. & Vanderbilt, D. Flux states and topological phases from spontaneous time-reversal symmetry breaking in CrSi(Ge)te3-based systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 257201 (2016).

Yu, R. et al. Quantized anomalous hall effect in magnetic topological insulators. Science 329, 61–64 (2010).

Jiang, H., Qiao, Z., Liu, H. & Niu, Q. Quantum anomalous hall effect with tunable chern number in magnetic topological insulator film. Phys. Rev. B 85, 045445 (2012).

Dong, L., Kim, L. Y., Er, D., Rappe, A. M. & Shenoy, V. B. Two-dimensional π-conjugated covalent-organic frameworks as quantum anomalous hall topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 096601 (2016).

Wang, Z. F., Liu, Z. & Liu, F. Quantum anomalous hall effect in 2d organic topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 196801 (2013).

Liu, C.-X., Qi, X.-L., Dai, X., Fang, Z. & Zhang, S.-C. Quantum anomalous hall effect in Hg1−yMnyTe quantum wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 146802 (2008).

Garrity, K. F. & Vanderbilt, D. Chern insulator at a magnetic rocksalt interface. Phys. Rev. B 90, 121103 (2014).

Fu, H. et al. Magnetic dirac fermions and chern insulator supported on pristine silicon surface. Phys. Rev. B 94, 035427 (2016).

Cook, A. M. & Paramekanti, A. Double perovskite heterostructures: Magnetism, chern bands, and chern insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 077203 (2014).

Cai, T. et al. Single-spin dirac fermion and chern insulator based on simple oxides. Nano Lett. 15, 6434–6439 (2015).

Xu, G., Wang, J., Felser, C., Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Quantum anomalous hall effect in magnetic insulator heterostructure. Nano Lett. 15, 2019–2023 (2015).

Wang, Z., Tang, C., Sachs, R., Barlas, Y. & Shi, J. Proximity-induced ferromagnetism in graphene revealed by the anomalous hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 016603 (2015).

Wang, Y.-P. et al. Discovery of intrinsic quantum anomalous hall effect in organic Mn-DCA lattice. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 233107 (2017).

Zhang, S.-J. et al. Intrinsic dirac half-metal and quantum anomalous hall phase in a hexagonal metal-oxide lattice. Phys. Rev. B 96, 205433 (2017).

Wang, X. L. Proposal for a new class of materials: Spin gapless semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 156404 (2008).

Liu, Z., Liu, J. & Zhao, J. Yn2 monolayer: Novel p-state dirac half metal for high-speed spintronics. Nano Res. 10, 1972–1979 (2017).

Zhang, X., Wang, A. & Zhao, M. Spin-gapless semiconducting graphitic carbon nitrides: A theoretical design from first principles. Carbon 84, 1–8 (2015).

He, J., Ma, S., Lyu, P. & Nachtigall, P. Unusual dirac half-metallicity with intrinsic ferromagnetism in vanadium trihalide monolayers. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 2518–2526 (2016).

He, J., Li, X., Lyu, P. & Nachtigall, P. Near-room-temperature chern insulator and dirac spin-gapless semiconductor: nickel chloride monolayer. Nanoscale 9, 2246–2252 (2017).

Ishizuka, H. & Motome, Y. Dirac half-metal in a triangular ferrimagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 237207 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Theory of the dirac half metal and quantum anomalous hall effect in mn-intercalated epitaxial graphene. Phys. Rev. B 92, 201403 (2015).

Wang, X.-L. Dirac spin-gapless semiconductors: promising platforms for massless and dissipationless spintronics and new (quantum) anomalous spin hall effects. National Sci. Rev. 4, 252–257 (2017).

Pardo, V. & Pickett, W. E. Half-metallic semi-dirac-point generated by quantum confinement in TiO2/VO2 nanostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 166803 (2009).

Li, S. S., Ji, W. X., Hu, S. J., Zhang, C. W. & Yan, S. S. Effect of amidogen functionalization on quantum spin hall effect in Bi/Sb(111) films. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter 9, 41443–41453 (2017).

McGuire, M. A., Dixit, H., Cooper, V. R. & Sales, B. C. Coupling of crystal structure and magnetism in the layered, ferromagnetic insulator cri3. Chem. Mater. 27, 612–620 (2015).

Hillebrecht, H. et al. Structural and scanning microscopy studies of layered compounds MCl3 (M = Mo, Ru, Cr) and MOCl2 (M = V, Nb, Mo, Ru, Os). J. All. Comp. 246, 70–79 (1997).

Zhang, W.-B., Qu, Q., Zhu, P. & Lam, C.-H. Robust intrinsic ferromagnetism and half semiconductivity in stable two-dimensional single-layer chromium trihalides. J. Mater. Chem. C 3, 12457–12468 (2015).

Bengel, H. et al. Tip-force induced surface corrugation in layered transition metal trichlorides MCl3 (M = Ru, Mo, Rh, Ir). Surf. Sci. 343, 95–103 (1995).

Nicolosi, V., Chhowalla, M., Kanatzidis, M.-G., Strano, M. S. & Coleman, J. N. Liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science 340, 6139 (2013).

Bafekry, A., Ghergherehchi, M. & Farjami Shayesteh, S. Tuning the electronic and magnetic properties of antimonene nanosheets via point defects and external fields: first-principles calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 10552–10566 (2019).

Zhang, C. First-principles study of ferromagnetism in two-dimensional silicene with hydrogenation. J. Phys. Chem. C 6, 4163–4166 (2012).

Bafekry, A., Stampfl, C., Shayesteh, S. F. & Peeters, F. M. Exploiting the novel electronic and magnetic structure of C3N via functionalization and conformation. Adv. Electron. Mater. 0, 1900459, https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.201900459 (2019).

Zhang, M.-H., Zhang, C.-W., Wang, P.-J. & Li, S.-S. Prediction of high-temperature chern insulator with half-metallic edge states in asymmetry-functionalized stanene. Nanoscale 10, 20226–20233 (2018).

Bafekry, A., Farjami Shayesteh, S. & Peeters, F. M. C3N monolayer: Exploring the emerging of novel electronic and magnetic properties with adatom adsorption, functionalizations, electric field, charging and strain. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 12485–12499 (2019).

Bafekry, A., Mortazavi, B. & Shayesteh, S. F. Band gap and magnetism engineering in dirac half-metallic NA2C nanosheet via layer thickness, strain and point defects. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 491, 165565 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Discovery of a novel spin-polarized nodal ring in a two-dimensional hk lattice. Nanoscale 10, 20748–20753 (2018).

Bafekry, A., Farjami Shayesteh, S. & Peeters, F. M. Introducing novel electronic and magnetic properties in C3N nanosheets by defect engineering and atom substitution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 21070–21083 (2019).

Bafekry, A., Shayesteh S. F. & Peeters, F. M. Tuning the band gap and introducing magnetism into monolayer BC3 by strain/defect engineering and adatom/molecule adsorption. J. Appl. Phys. 126 144304 (2019).

Bafekry, A., Stampfl, C., Ghergherehchi, M. & Farjami Shayesteh, S. A first-principles study of the effects of atom impurities, defects, strain, electric field and layer thickness on the electronic and magnetic properties of the C2N nanosheet. Carbon 157, 371, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2019.10.038 (2020).

Bafekry, A. Graphene-like BC6N single-layer: Tunable electronic and magnetic properties via thickness, gating, topological defects, and adatom/molecule. Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems and Nanostructures 118, 113850, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2019.113850 (2019).

Bafekry, A., Farjami Shayesteh, S. & Peeters, F. M. Two-dimensional carbon nitride (2DCN) nanosheets: Tuning of novel electronic and magnetic properties by hydrogenation, atom substitution and defect engineering. J. Appl. Phys. 126(21), 215104, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5120525@jap.2020 (2020).

Bafekry, A., Akgenc, B., Shayesteh S. F. & Mortazavi, B. Tunable electronic and magnetic properties of graphene/carbon-nitride van der Waals heterostructures. Appl. Surf. Sci. 144450, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144450 (2019).

Bafekry, A., Stampfl, C., Akgenc, B. & Ghergherehchi, M. Control of C3N4 and C4N3 carbon nitride nanosheets’ electronic and magnetic properties through embedded atoms. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., https://doi.org/10.1039/C9CP06031F.

Bafekry, A., Stampfl, C. & Farjami Shayesteh, S. A first‐principles study of C3N nanostructures: Control and engineering of the electronic and magnetic properties of nanosheets, tubes and ribbons. ChemPhysChem. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201900852.

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Troullier, T. & Martins, J. L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B 43, 1993–2006 (1991).

Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for large-scale electronic structures. Phys. Rev. B 67, 155108 (2003).

Ozaki, T. & Kino, H. Numerical atomic basis orbitals from H to Kr. Phys. Rev. B 69, 195113 (2004).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Bucko, T., Hafner, J., Lebegue, S. & Angyan, J. G. Improved description of the structure of molecular and layered crystals: Ab initio dft calculations with van der waals corrections. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 11814–11824 (2010).

Mulliken, R. S. Electronic Population Analysis on LCAOMO Molecular Wave Functions. IV. Bonding and Antibonding in LCAO and Valence Bond Theories. J. Chem. Phys. 23, 2343–2346 (1955).

Tersoff, J. & Hamann, D. R. Theory and application for the scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 50, 1998–2001 (1983).

Horcas, I. et al. WSxM: A software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Inst. 78, 013705 (2007).

Soler, J. M. et al. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-n materials simulation. J. Phys.: Condens. Matt. 14, 2745 (2002).

Wang, Y.-P. et al. High-temperature Dirac half-metal PdCl3: a promising candidate for realizing quantum anomalous Hall effect. J. Mater. Chem. C 6, 10284–10291 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Flemish Science Foundation (FWO-Vl). We are thankful for comments by Sevil Sarikurt from the department of physics in Dokuz Eylul University. In addition, we acknowledge OpenMX team for OpenMX code.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B. performed the calculations and wrote the manuscript. C.S. and F.P. provided scientific input and direction and assisted with writing and finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bafekry, A., Stampfl, C. & Peeters, F.M. Dirac half-metallicity of Thin PdCl3 Nanosheets: Investigation of the Effects of External Fields, Surface Adsorption and Defect Engineering on the Electronic and Magnetic Properties. Sci Rep 10, 213 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57353-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57353-3

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.