Abstract

Age-related changes in the brain can alter how emotions are processed. In humans, valence specific changes in attention and memory were reported with increasing age, i.e. older people are less attentive toward and experience fewer negative emotions, while processing of positive emotions remains intact. Little is yet known about this “positivity effect” in non-human animals. We tested young (n = 21, 1–5 years) and old (n = 19, >10 years) family dogs with positive (laugh), negative (cry), and neutral (hiccup, cough) human vocalisations and investigated age-related differences in their behavioural reactions. Only dogs with intact hearing were analysed and the selected sound samples were balanced regarding mean and fundamental frequencies between valence categories. Compared to young dogs, old individuals reacted slower only to the negative sounds and there was no significant difference in the duration of the reactions between groups. The selective response of the aged dogs to the sound stimuli suggests that the results cannot be explained by general cognitive and/or perceptual decline. and supports the presence of an age-related positivity effect in dogs, too. Similarities in emotional processing between humans and dogs may imply analogous changes in subcortical emotional processing in the canine brain during ageing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Changes in the brain during ageing influence how adults process emotions1. Whereas the processing of positive emotions remains more or less stable, older adults experience fewer negative emotions. This phenomenon, referred to as age-related positivity effect, is present both in attention and memory2. For example, Mather & Carstensen3 found that older adults spent less time looking at negative features of portraits than on positive features, and that the time spent looking at negative features was shorter than in younger adults. This form of selective attention has an effect on memory, because higher attention to positive features can lead to stronger memories4.

The positivity effect was also observed in the auditory domain, in regard to processing emotional prosody and valence. Prosody is defined as the properties of larger units of vocalisations that can indicate the emotional state of a speaker5, and valence describes the attractiveness/averseness or emotional association of a stimulus6. Older adults have more trouble identifying emotional valence in sounds and pitch perception of emotional prosody can be impaired as well7,8. A cross-sectional study on the perception of both sounds and faces with different emotional valences showed that aged adults have a decreased ability to recognise both sadness and anger, whereas the recognition of other emotions remained intact9.

As in humans, the functions of the canine brain are known to decline with age10. Both the cognitive functions of the medial temporal lobe and the prefrontal cortex are impaired in old dogs, as demonstrated in an indirect behavioural study by Head et al.11. In this study, older dogs performed worse on several cognitive behaviour tests that were used to assess age-dependent cognitive decline. This was later supported by several other behavioural studies12,13,14,15. An MRI study by Tapp et al.16. confirmed that in 8–15 year old beagles the frontal lobe and the hippocampal volumes declined with age. Similar ageing effects have been found in other animal models, including mice17, rats18, cats19 and primates20. However, while age-effects on responsiveness in regard to certain sound characteristics like frequency have been studied in animal models21, age-effects in the processing of emotionally loaded stimuli have not been studied in non-human animals yet. Information will add to our knowledge about the evolution of emotion-processing and the validity of animal species as aging models.

Family dogs are able to differentiate between human emotions. For instance, dogs were able to discriminate between happy and blank faces on photographs22 and they were most reactive to commands when their owners displayed happiness instead of neutrality or disgust with body language and sound23. A cross-modal, preferential looking paradigm study showed that dogs spontaneously paired positive and negative emotions of both human and conspecific faces on pictures with pre-recorded emotional sounds24. Emotion processing was also tested in the head turning paradigm, where dogs reacted differently towards positive and negative sounds. This supports that dogs spontaneously discriminate between positive and negative human emotions. In addition to discriminating between the emotions, research on emotional contagion has shown that dogs are affected by both visual and auditory emotional expressions. Dogs licked their mouth more frequently when they faced pictures of human and dog faces with negative emotional expression, regardless the valence of the sound presented at the same time25. Dogs showed significantly more arousal and stress related behaviours following negative emotional sounds compared to positive and non-emotional sounds they were exposed to, suggesting they matched the emotional valence in the negative sounds26. Using a non-invasive functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) procedure with awake dogs and humans, Andics et al.27 showed the existence of specific voice areas and the presence of emotional valence sensitivity in dogs’ brains.

We hypothesised that dogs show age-related positivity effect similar to humans, as both the general age-related changes in the brain, and the brain regions involved in auditory processing are similar in humans and dogs. Specifically, the present study focused on whether there are age-related differences in the spontaneous behavioural reaction of dogs to human vocalisations with positive, negative, and neutral emotional valences during a sound playback test. We decided to use human vocalisations because (1) we have less information regarding the perceived valence of dog vocalisations by other dogs and (2) not all type of dog vocalisations are directed to other dogs, some vocalisations have been showed to be human directed28. This could lead to unexpected variations in the interpretation of the sounds by the dogs. (3) The huge variance in body size among dogs has the potential to introduce additional confounding factors (e.g. a small dog or a dog with negative previous experiences may perceive certain dog vocalisations as more threatening, while from some large dogs small dog vocalizations may elicit predatory responses)29, which we wanted to exclude. We compared latency to react and the latency of recovery of aged and young dogs with intact hearing. Via this setup we investigated whether aged dogs were (1) less responsive to all sounds in general due to e.g. general cognitive decline or (2) selectively less responsive toward negative stimuli than young dogs corresponding to a positivity effect.

Methods

Ethics statement

The behavioural observations conducted in this study were not identified as animal experiments by the Hungarian Animal Protection Act (“1998. évi XXVIII. Törvény”, 3. §/9.), which identifies animal experiments, as this study was non-invasive. The application number of the ethical commission for studies performed by the Senior Family Dog Project is PE/EA/2019-5/2017. Each owner filled in a consent form stating that they have been informed of the tests.

Subjects

A total of 46 family dogs were tested, of which six had to be excluded from the analysis. Reasons for exclusion included excessive stress reactions to the sounds (n = 1), hearing impairments (n = 1), owner interference during the sound playback (n = 1) and technical problems (n = 3). Finally, n = 21 young dogs (1–5 years) and n = 19 old (>10 years) dogs were analysed in the study. Only dogs between 4 and 30 kg took part in the study, with a mean weight of 17 for old dogs and 16 for young dogs. This restriction was implemented because dogs with different sizes could exhibit a difference in aging rate. The female to male ratio was 2:5 (6:15 female to male for the young age group and 6:13 for the old age group). The dogs were required to be experimentally naive for sound playback studies. The hearing of the subjects was assessed by calling the dogs’ name and via using a rattler behind them, by both the owner and the experimenter in a test following the experiment. Dogs which showed any signs of hearing impairments were excluded from the analysis (n = 1). Owners were recruited via online promotion and from the Department of Ethology’s database.

Test room

The tests were conducted at a room of the Department of Ethology. The room measured 3.10 × 5.40 metres. The owner was positioned on a chair in the back of the room (1 metre from the front wall) facing the speaker set (2× Logitech S-02648, 230 V ~50 Hz 40 mA), which were placed together 2 metres in front of the chair with a 38 cm distance between the two speakers (Fig. 1). The experimenter was standing next to camera 1, positioned next to the wall 1.25 metres away from the chair. Camera 2 was positioned 80 centimetres behind the speakers. The speakers were connected to a laptop and a media pointer was used to change the sounds using PowerPoint. The dog was positioned in front of the owner, with its back to the speakers, facing either the owner or the side walls.

Test room set-up. The owner was positioned in the back of the room and the leashed dog was laying down in front of them. The experimenter was standing next to camera 1, 1.25 meters away from the owner and dog. Camera 2 was positioned behind the speakers, which were positioned 2 meters in front of the owner. The owner was reading a magazine and listening to music via headphones to minimise their effect on the dog’s reaction.

Stimuli

The 6 stimuli used (2 positive, 2 negative, 2 neutral, all non-linguistic) were pre-selected from published studies. The positive and negative sounds were chosen from a study by Anikin & Persson30 that validated a corpus of 260 human vocalisations using a survey on 90 participants with different nationalities who rated the sounds. They were non-acted sounds taken from real life video clips. The negative sounds featured a cry by a male and a female and the positive sounds were a male and a female laugh. As this corpus lacked neutral vocalisations, the two neutral stimuli, a hiccup and a cough, were sound effects taken from Youtube. The cough was male and the gender of the hiccup sound was not identified in the description of the source video. All stimuli had a duration of 5 seconds, were recorded in mono and had a RMS volume of 20 dB, limited on −3.5 dB with a soft limiter. The sounds were edited using Audacity 2.2.2. Further details of the sounds can be found in Table 1.

Logarithmic power spectral density was calculated using the Long Term Average Spectrum (LTAS) function in31, with a 100 Hz bandwidth between bands of 0–1000 and 1000–4000. For the resulting values see Table 2. Sonograms of the sounds (Fig. 2), with a range of 0–6000 Hz and a 0.05 s time window and 60 dB dynamic range, were created using Praat.

The play level of the sounds was measured using a Voltcraft SL-200 Digital Sound Level Meter, 2 meters from the speakers. The mean level of the sounds during the experiment was 70.08 dB with a reference level of (x microPa) and the background sound level had an average of 39.2 dB.

Procedure

The owner was sitting on the chair reading a magazine and listening to music, therefore the test sounds were inaudible for him/her. The dog was given time to acclimatise and lie down on its own. If it did not lie down within a minute, or if it lied down facing the speakers, the owner was asked to position the dog in front of him/her so it was laying down with either its back or side to the speakers. Once the dog lied down and was looking away from the speaker, the sound playback started, and the first sound (testSTIM1) was played. Once the dog recovered from the sound, but at least 10 seconds later and maximum 1 minute later, the owner was asked to reposition the dog if necessary. Once the dog was again not focused on environmental stimuli (i.e. it was passive), the second sound (testSTIM2) was played. This was repeated for the third sound (testSTIM3). After a 5-minute break outside the test room in which the owner was free to interact with the dog, the trial was repeated with the 4th–6th sounds (testSTIM4, 5 and 6). The playbacks of testSTIM1–6 were semi-randomised for each subject. Each session contained 1 positive, 1 negative and 1 neutral stimulus, therefore after the two sessions all subjects were exposed to two positive, two negative and two neutral stimuli. Video recording of the dogs’ behaviour happened continuously during the trials and the behaviours were analysed based on the videos.

Data collection

Latency to react. Time in milliseconds from stimulus onset till the dog started its head/ear turn towards the source of the sound. We stopped the observation after 10 seconds.

Latency to recover. Time in milliseconds from latency to react until the dog started to turn away from the source of the sound. We stopped the observation after 60 seconds.

One observer scored the latencies and behaviours blindly, without hearing the sounds during scoring, after which the same observer coded the latencies using the audio stream for determining stimulus onset, based on the previously coded reactions. The second observer scored 120 trials using the same method.

Statistical analysis

R (version 3.5.1.) was used for the statistical analysis32. Inter-observer reliability analysis of the latencies was calculated via coding 25% of the data by a second, trained coder. Agreement was calculated using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) in a two-way mixed-effects model with a 95% confident interval on consistency in SPSS 2233. Normality of the latency to react and latency to recover was checked using Q-Q normality plots, which showed neither of the variables were normally distributed. Because of censoring within the reactivity and latency data (e.g. when the dog did not react within 10 seconds or when the dog did not redirect its attention within 60 seconds), Survival Analysis Methods were used.

First, to check whether there were any differences between the two samples within the categories we used Kaplan Meier estimates with the main factor of Sound ID and a post-hoc pair-wise comparison. Survival analysis was used because right censoring occurred during the tests. To compare the reaction and recover latencies of young and old dogs Kaplan Meier estimates were used, with the main factors being age group and sound category. Mixed Effects Cox Regression Models were used to analyse the effects of age group, emotion category and playback order on the latency to react and recover with subjects as random variable and the sound categories, trial order and the dogs’ age as factor. The young age group, the neutral sound category and trial 1 were set as reference categories. Cox proportional hazards were used to analyse the confidence intervals. Since there was a trial effect, the Cox models were also run on a dataset including only the first trial for each dog. The dogs that did not react were classified as censored within the latency to react model and not used in the latency to recover model. Dogs that did not recover were classified as censored in the latency to recover model in that specific trial. Exploratory analysis with a dredge function in R showed no suggested effects of sex, thus it was excluded from the models. The dredge function also showed improved models without interactions.

Reactivity and recovery were also tested with a binominal Generalized linear mixed model to compare the number of censored trials of the old and young dogs in the different sound categories. It also included the factors age group, sound category and trial, using the subject as random variable.

Results

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for latency to react and latency to recover were excellent (0.924 and 0.793, respectively).

A log-rank test revealed no differences in the latencies to react and recover between the two different sounds within a category. Based on this, we analysed the reactions within a valence category (e.g. cry1 and cry2) together.

Latency to react

Out of a total of 240 trials, there were 23 trials (from 15 dogs) in which the dog did not react within 10 seconds from the onset of the stimuli (Table 3). This resulted in a total of 117 trials with young dogs with a mean reaction time of 1231.43 msec (SD = 2631.10) and 100 trials with old dogs with a mean reaction time of 1686.84 msec, SE = 3179.12). A generalized linear mixed model with binomial distribution showed no significant effects of age group (β = −0.76, SE = 0.69, p = 0.27) or sound category (positive: (β = 0.14, SE = 0.63, p = 0.81), negative: (β = −0.07, SE = 0.60, p = 0.90)) on the dogs’ reactivity. However, a trial effect was found, dogs were less likely to react in Trial 6 than in Trial 1 (β = −2.23, SE = 0.91, p = 0.014).

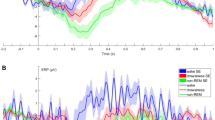

Survival probability

A log-rank test showed that old dogs responded to the sounds with a longer latency (Chi X2 = 5.2 p = 0.02) (Fig. 3). The difference between young and old dogs within the negative sound category was significant (Young: (95%CI: 300; 300), Old: (95%CI: 300; 800), p = 0.021). Within the negative sound category, young dogs showed an increased hazard to react compared to the old dogs (Fig. 4). We found no similar pattern within the neutral (Young: (95%CI: 300; 400), Old: (95%CI: 300; 400), p = 0.913) or the positive sound category (Young: (95%CI: 300; 400), Old: (95%CI: 300; 400), p = 0.521). This indicates that old dogs reacted significantly slower than young dogs only in the negative sound category.

Cumulative hazards plot for the latency to react, grouped per age and sound category. The positive, neutral and negative sound categories are represented by the green, yellow and red coloured lines respectively. The young age group is shown with a solid line and the old age group with an interrupted line.

Mixed effects cox regression

We tested whether dogs became habituated to the sounds across trials via a Mixed Effects Cox regression model. The cumulative hazard results of the Cox regression showed a significant hazard decrease (exp(β) = <1) in trial 5 and 6, of 0.56 (exp(β) = 0.57, 95%CI = (0.37;0.94), p = 0.03) and 1.04 (exp(β) = 0.35, 95%CI = (0.25;0.67), p < 0.001) respectively (for statistical details see Table 4). An exp(β) below 1 for these factors suggests an increased latency to react, i.e. dogs habituated to the sounds in trial 5 and 6.

Latency to recover

The trials where the dogs did not react were excluded (due to the lack of latency to recover), resulting in a total of 217 trials being used for the analysis of the latency to recover. Out of a total of 217 trials in which the dog reacted, 5 dogs did not recover in 8 different trials (i.e. did not return to passive, unfocused state) within the time limit of 60 seconds after the onset of sound, or before another event, (e.g. due to owner interference or external distraction) (Table 3). The 116 trials with young dogs had a mean recovery time of of 10381.2 msec (SD = 7802.38) and old dogs had a mean of 10566 msec (SE = 11554.65).

Survival probability

The log-rank test showed that there was no significant difference in the latency to recover between young and old dogs (Young: (95% CI: 7700msec; 9800 msec), Old: (95% CI: 6100 msec; 9100 msec), p > 0.9). A Cumulative Hazard analysis paired with a log-rank test showed no age differences in recovery time from the negative (Young: (95%CI: 7500; 10700), Old: (95% CI: 7000; 13000), p = 0.93), positive (Young: (95% CI: 7300; 11300), Old: (95% CI :5500; 9100), p = 0.93) or neutral (Young: (95% CI: 7100; 11100), Old: (95% CI: 5600; 10800), p = 0.93) sounds. This indicates that there was no significant difference in latency to recover between young and old dogs in any sound category.

Mixed effects cox regression

The results of the Cox model (Cox mixed-effects model fit by maximum likelihood) showed a significant effect only in case of trial 4 (for statistical details see Table 5). The hazard of the latency to recover increased (exp(β) = > 1) in trial 4 by 0.19 (exp(β) = 2.25, 95% CI = (1.14;2.88), p = 0.001), showing that the dogs had a significantly shorter latency to recover during the first trial after the short break.

Discussion

Cognitive decline in older dogs, which is thought to be linked to the temporal and frontal cortex34 can cause longer processing, namely slower reaction times and a longer latency to recover11,16,35. However, in the current study we showed that older dogs are not simply less responsive or slower to respond to the used stimuli in general. Latency to react did differ significantly between young and old dogs, but only in the negative sound category where the young dogs reacted faster than the old dogs, while latency to recover was not different between young and old dogs. The number of not recovering dogs also did not significantly differ between the old and young dogs across the different sound categories. Thus, it can be concluded that the old dogs that passed the hearing test were not less responsive to all sounds and the difference is more likely caused by changes in the processing of certain sound types than by general cognitive decline.

While attention span is generally decreased in older dogs36 and the likelihood to recover is smaller than in younger dogs35, we found no differences between old dogs and young dogs in whether they recovered from the stimuli within 60 seconds. Most dogs kept their attention towards the speakers after the sound with a duration of 5 seconds had ended, suggesting that the latency to recover in the current setup may not indicate attention to the sound per se but rather the behavioural changes following the arousal induced by it. Testing the phenomenon in a different setup, for example with projected images like in Racca et al.37 could provide information whether attention span toward emotional stimuli also changes in aging dogs. Alternatively, comparing the performance of young and old dogs trained to classify portraits based on the displayed emotions38 could reveal whether the positivity effects extends into the classification performance of old dogs and whether attention toward negative stimuli is selectively decreased in old dogs during an active choice task.

It is suggested that prosody discrimination in humans is, among other factors, is based on the duration and fundamental frequency of the sounds39,40. The effect of differences in prosody in dogs has been observed in regard to stress and arousal indicating behaviours25,26. The sounds used in this study were similar in their fundamental frequency (Table 1) and they all had a duration of 5 seconds. Additionally, in the selected sound set the negative samples did not deviate strongly from the other samples (the two negative samples were not the two most extreme ones neither regarding mean nor fundamental frequencies, see Table 1), meaning that the findings cannot be explained based on e.g. diminished reactivity to above/below a certain frequency range.

After multiple human studies reporting an age-related positivity effect9,41,42, the results of our study suggests the presence of a similar valence related phenomenon in dogs. While a previous study by Siniscalchi et al.35, in line with our current results showed a significant difference between young and old dogs in reactivity to emotional sounds in general, our study is the first to look at the role of valence in reactions of aging dogs and the presence of the positivity effect. Further studies including more emotional categories are needed to investigate the level of similarity between positivity effect in dogs and humans, for instance whether the processing of other negative emotional vocalisation (e.g. anger) are also affected in dogs, similarly to humans9.

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain the positivity effect in humans. The two main mechanisms differ in regard to their complexity, required level of abstract thought and the involved brain areas. The ageing-brain model ascribes changes in the processes in the anterior cingulate gyrus to downregulate the response of the amygdala to negative stimuli and thereby influence the way these emotions are processed and reacted upon2,43. Downregulating the amygdala has been connected to a higher level of emotional control and emotion regulation44. In contrast, the Emotional Selectivity Theory3 proposed the role of cognitive control in the shift in attention and memory away from negative towards more positive emotions. Based on the Emotional Selectivity Theory, these changes are caused by greater emotion regulation of older adults, and a change in perception of experiences, with positive experiences being valued higher by older individuals due to awareness of time left alive3,43. Since dogs are less likely to reflect upon their longevity and ultimate death and have yet to show signs of both emotion regulation and awareness of future life events, the current results cannot be explained by a positivity effect resulting from the Emotional Selectivity Theory. Thus, the presence of an age-related positivity effect in dogs supports the ageing-brain model.

Degeneration in the brain of older dogs is mainly found in the frontal and temporal cortex34. Processing of auditory stimuli is associated with the temporal lobe, while the attention to stimuli is regulated in the frontal lobe45. An effect of the similar degeneration in humans is presbycusis, the reduced ability to differentiate between acoustic properties and hearing loss. For example, older individuals have trouble identifying differences in sound duration, hearing short silent gaps in an auditory stimuli (temporal gap detection)46, hearing in noisy environments, speech processing47 and discrimination of complex stimuli48. Presbycusis is induced by cochlear degeneration, which causes hearing loss, primarily to the mid to high frequencies49. Loss of cochlear function has the same effect in dogs50. Ter Haar et al. found that hearing loss starts in dogs of around 8 years of age and are most prominent in frequencies ranging from 8–32 kHz51. In the current study, the negative sounds did not differ in frequency and average spectral density from the positive and neutral sounds, suggesting that presbycusis in the old dogs is not the cause of the differences in the latency to react.

There are multiple similarities in the processing of emotional human sounds in both the primary and secondary auditory regions between humans and dogs27. Processes and interactions involved in the prosody discrimination are also suggested to take place mainly in the frontal and temporal lobe52,53,54,55; where the anterior cingulate gyrus (in the primary auditory cortex of the temporal cortex) and amygdala (in the prefrontal cortex) are located. With age, the amygdala is known to decrease in volume56 and this is shown to affect the way emotional cues are processed in humans57.

There are two general pathways for auditory processing in the brain; the thalamic, or subcortical, and the cortical pathway58,59. It has been suggested that the subcortical pathway subconsciously processes sounds and visual stimuli before the cortical level, to provide the amygdala with a brief preliminary characterisation before further and slower processing using the cortical pathway takes place59,60. Auditory nerve fibres located in the brainstem are involved in the preliminary processing of fundamental frequency and harmonic cues in sounds61. Harmonic cues, like timbre, are used by the auditory regions in the brainstem to encode sounds that are not easily recognisable by frequency62. Auditory brainstem response (ABR) peaks are seen to be reduced in older adults, which suggests that the number and synchrony of the auditory nerve fibres are reduced63.

The fact that in our study the latency to react, but not the latency to recover showed significant differences between the old and young dogs in the negative sound category may suggest that the age-related changes take place in subcortical processing rather than in cortical processing, involving both the ageing of auditory nerve fibres of the brainstem and the degeneration of the amygdala. However, further research involving brain imaging is necessary to determine the specific cause of these effects, the brain regions involved and nature of the differences. Studying age-related differences in the processing of emotional stimuli in animals allows us to deepen our understanding regarding the positivity effect in different species and can give us more insight into the biological changes of the ageing brain, affecting how older individuals perceive and process their social environment.

Data availability

All data generated during or analysed during the current study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). The supplementary dataset contains all measured variables.

References

Cacioppo, J. T. Could an Aging Brain Contribute to Subjective Well-Being?: The Value Added by a Social Neuroscience Perspective. In Social Neuroscience: Toward Understanding the Underpinnings of the Social Mind (eds. Todorov, A., Fiske, S. & Prentice, D.) 249–262, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195316872.003.0017 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Reed, A. E. & Carstensen, L. L. The theory behind the age-related positivity effect. Front. Psychol. 3, 1–9 (2012).

Mather, M. & Carstensen, L. L. Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 496–502 (2005).

Logan, G. D. An instance theory of attention and memory. Psychol. Rev. 109, 376–400 (2002).

Dimos, K., Dick, L. & Dellwo, V. Perception of levels of emotion in speech prosody.

Ford, C. E., Wright, R. A. & Haythornthwaite, J. Task performance and magnitude of goal valence. J. Res. Pers. 19, 253–260 (1985).

Mitchell, R. L. C. Age-related decline in the ability to decode emotional prosody: Primary or secondary phenomenon? Cogn. Emot. 21, 1435–1454 (2007).

Mitchell, R. L. C. & Kingston, R. A. Age-related decline in emotional prosody discrimination: Acoustic correlates. Exp. Psychol. 61, 215–223 (2014).

Mill, A., Allik, J., Realo, A. & Valk, R. Age-Related Differences in Emotion Recognition Ability: A Cross-Sectional Study. Emotion 9, 619–630 (2009).

Borras, D., Ferrer, I. & Pumarola, M. Age-related changes in the brain of the dog. Vet. Pathol. Online 36, 202–11 (1999).

Head, E., Mehta, R., Hartley, J. & Kameka, M. Spatial Learning and Memory as a Function of Age in the Dog. Behav. Neurosci. 109, 851–858 (1995).

Milgram, N. W., Head, E., Weiner, E. & Thomas, E. Cognitive functions and aging in the dog: Acquisition of nonspatial visual tasks. Behav. Neurosci. 108, 57–68 (1994).

Mongillo, P. et al. Spatial reversal learning is impaired by age in pet dogs. Age (Omaha). 35, 2273–2282 (2013).

Rosen, A. et al. Variable effects of aging on frontal lobe contributions to memory. Variable e ¡ ects of aging on frontal lobe contributions to memory. Neuroreport 13, 2425–2428 (2002).

Wallis, L. J. et al. Aging effects on discrimination learning, logical reasoning and memory in pet dogs. Age (Omaha). 38, 6 (2016).

Tapp, P. D. et al. Frontal Lobe Volume, Function, and -Amyloid Pathology in a Canine Model of Aging. J. Neurosci. 24, 8205–8213 (2004).

Forster, M. J. et al. Age-related losses of cognitive function and motor skills in mice are associated with oxidative protein damage in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 4765–9 (1996).

Fischer, W., Gage, F. H. & Bjorklund, A. Degenerative Changes in Forebrain Cholinergic Nuclei Correlate with Cognitive Impairments in Aged Rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1, 34–45 (1989).

Youssef, S. A. et al. Pathology of the Aging Brain in Domestic and Laboratory Animals, and Animal Models of Human Neurodegenerative Diseases. Vet. Pathol. 53, 327–48 (2016).

Alexander, G. E. et al. Age-Related Regional Network of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Gray Matter in the Rhesus Macaque. J. Neurosci. 28, 2710–2718 (2008).

Walton, J. P. Timing is everything: Temporal processing deficits in the aged auditory brainstem. Hear. Res. 264, 63–69 (2010).

Nagasawa, M., Murai, K., Mogi, K. & Kikusui, T. Dogs can discriminate human smiling faces from blank expressions. Anim. Cogn. 14, 525–533 (2011).

Turcsán, B., Szánthó, F., Miklósi, Á. & Kubinyi, E. Fetching what the owner prefers? Dogs recognize disgust and happiness in human behaviour. Anim. Cogn. 18, 83–94 (2015).

Albuquerque, N. et al. Dogs recognize dog and human emotions. Biol. Lett. 12, 20150883 (2016).

Albuquerque, N., Guo, K., Wilkinson, A., Resende, B. & Mills, D. S. Mouth-licking by dogs as a response to emotional stimuli. Behav. Processes 146, 42–45 (2018).

Huber, A., Barber, A. L. A., Faragó, T., Müller, C. A. & Huber, L. Investigating emotional contagion in dogs (Canis familiaris) to emotional sounds of humans and conspecifics. Anim. Cogn. 20, 703–715 (2017).

Andics, A., Gácsi, M., Faragó, T., Kis, A. & Miklósi, A. Voice-sensitive regions in the dog and human brain are revealed by comparative fMRI. Curr. Biol. 24, 574–578 (2014).

Siniscalchi, M., d’Ingeo, S., Minunno, M. & Quaranta, A. Communication in dogs. Animals 8 (2018).

Faragó, T., Pongrácz, P., Range, F., Virányi, Z. & Miklósi, Á. ‘The bone is mine’: affective and referential aspects of dog growls. Anim. Behav. 79, 917–925 (2010).

Anikin, A. & Persson, T. Nonlinguistic vocalizations from online amateur videos for emotion research: A validated corpus. Behav. Res. Methods 49, 758–771 (2017).

Boersma, P. P. a system for doing phonetics by computer. Glot Int. 5, 341–345 (2001).

R Core Team & R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (2018).

Corp., I. SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 22, 0 (2013).

Head, E. Neurobiology of the aging dog. Age (Dordr). 33, 485–96 (2011).

Siniscalchi, M., D’Ingeo, S., Fornelli, S. & Quaranta, A. Lateralized behavior and cardiac activity of dogs in response to human emotional vocalizations. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–12 (2018).

Wallis, L. J. et al. Lifespan development of attentiveness in domestic dogs: drawing parallels with humans. Front. Psychol. 5, 71 (2014).

Racca, A., Guo, K., Meints, K. & Mills, D. S. Reading faces: Differential lateral gaze bias in processing canine and human facial expressions in dogs and 4-year-old children. PLoS One 7, 1–10 (2012).

Müller, C. A., Schmitt, K., Barber, A. L. A. & Huber, L. Dogs Can Discriminate Emotional Expressions of Human Faces. Curr. Biol. 25, 601–605 (2015).

Marx, M. et al. Speech Prosody Perception in Cochlear Implant Users With and Without Residual Hearing. Ear Hear. 36, 239–248 (2015).

Farago, T. et al. Humans rely on the same rules to assess emotional valence and intensity in conspecific and dog vocalizations. Biol. Lett. 10, 20130926–20130926 (2014).

Brosgole, L. & Weisman, J. Mood recogition across the ages. Int. J. Neurosci. 82, 169–189 (1995).

Ryan, M., Murray, J. & Ruffman, T. Aging and the perception of emotion: Processing vocal expressions alone and with faces. Exp. Aging Res. 36, 1–22 (2010).

Nashiro, K., Sakaki, M. & Mather, M. Age differences in brain activity during emotion processing: Reflections of age-related decline or increased emotion regulation? Gerontology 58, 156–163 (2012).

Herwig, U. et al. Training emotion regulation through real-time fMRI neurofeedback of amygdala activity. Neuroimage 184, 687–696 (2019).

Baars, B. J. & Gage, N. M. The brain. in Cognition, Brain, and Consciousness 126–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375070-9.00005-X (Academic Press, 2010).

Fitzgibbons, P. J. & Gordon-Salant, S. Auditory temporal processing in elderly listeners. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 7, 183–9 (1996).

Pichora-Fuller, M. K. & Souza, P. E. Effects of aging on auditory processing of speech. Int. J. Audiol. 42(Suppl 2), 2S11–6 (2003).

Fitzgibbons, P. J. & Gordon‐Salant, S. Age effects on duration discrimination with simple and complex stimuli. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 98, 3140–3145 (1995).

Schuknecht, H. F. & Gacek, M. R. Cochlear Pathology in Presbycusis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 102, 1–16 (1993).

Knowles, K., Blauch, B., Leipold, H., Cash, W. & Hewett, J. Reduction of Spiral Ganglion Neurons in the Aging Canine with Hearing Loss. J. Vet. Med. Ser. A 36, 188–199 (1989).

ter Haar, G., Venker-van Haagen, A. J., van den Brom, W. E., van Sluijs, F. J. & Smoorenburg, G. F. Effects of Aging on Brainstem Responses to Toneburst Auditory Stimuli: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study in Dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 22, 937–945 (2008).

Canli, T., Zhao, Z., Desmond, J. E., Glover, G. & Gabrieli, J. D. E. fMRI identifies a network of structures correlated with retention of positive and negative emotional memory. Psychobiology 27, 441–452 (1999).

Hamann, S. Cognitive and neural mechanisms of emotional memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 5, 394–400 (2001).

Bush, G., Luu, P. & Posner, M. I. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 215–222 (2000).

Vogt, B. A. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 533–544 (2005).

Allen, J. S., Bruss, J., Brown, C. K. & Damasio, H. Normal neuroanatomical variation due to age: The major lobes and a parcellation of the temporal region. Neurobiol. Aging 26, 1245–1260 (2005).

De Winter, F.-L. et al. Amygdala atrophy affects emotion-related activity in face-responsive regions in frontotemporal degeneration. Cortex 82, 179–191 (2016).

Lee, C. C. Thalamic and cortical pathways supporting auditory processing. Brain Lang. 126, 22–8 (2013).

Pannese, A., Grandjean, D. & Frühholz, S. Subcortical processing in auditory communication. Hear. Res. 328, 67–77 (2015).

Pessoa, L. & Adolphs, R. Emotion processing and the amygdala: from a ‘low road’ to ‘many roads’ of evaluating biological significance. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 773–83 (2010).

Felix, R. A., Gourévitch, B. & Portfors, C. V. Subcortical pathways: Towards a better understanding of auditory disorders. Hear. Res. 362, 48–60 (2018).

de Cheveigné, A. Separation of concurrent harmonic sounds: Fundamental frequency estimation and a time‐domain cancellation model of auditory processing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 93, 3271–3290 (1993).

Konrad-Martin, D. et al. Age-related changes in the auditory brainstem response. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 23, 18–35; quiz 74–5 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anna Egerer and Zsófia Réti for their help with the recruitment, their assistance with conducting the experiments and for coding for reliability analysis, Tamás Faragó for his advice regarding experimental setup and the sound analysis and visualisation and Patrizia Piotti for her help in the statistical analysis. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement No. 680040), the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (Grant No 115862 K), Bolyai János Research Scholarship from the HAS for EK and an Erasmus + traineeship grant from the EC for IS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S.Z., E.K. and I.S. conceived the experiments, I.S. conducted the experiments, I.S. and D.S.Z. analysed the results, IS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smit, I., Szabo, D. & Kubinyi, E. Age-related positivity effect on behavioural responses of dogs to human vocalisations. Sci Rep 9, 20201 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56636-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56636-z

This article is cited by

-

Two valid and reliable tests for monitoring age-related memory performance and neophobia differences in dogs

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Occurrences of non-linear phenomena and vocal harshness in dog whines as indicators of stress and ageing

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.