Abstract

In bonobos, strong bonds have been documented between unrelated females and between mothers and their adult sons, which can have important fitness benefits. Often age, sex or kinship similarity have been used to explain social bond strength variation. Recent studies in other species also stress the importance of personality, but this relationship remains to be investigated in bonobos. We used behavioral observations on 39 adult and adolescent bonobos housed in 5 European zoos to study the role of personality similarity in dyadic relationship quality. Dimension reduction analyses on individual and dyadic behavioral scores revealed multidimensional personality (Sociability, Openness, Boldness, Activity) and relationship quality components (value, compatibility). We show that, aside from relatedness and sex combination of the dyad, relationship quality is also associated with personality similarity of both partners. While similarity in Sociability resulted in higher relationship values, lower relationship compatibility was found between bonobos with similar Activity scores. The results of this study expand our understanding of the mechanisms underlying social bond formation in anthropoid apes. In addition, we suggest that future studies in closely related species like chimpanzees should implement identical methods for assessing bond strength to shed further light on the evolution of this phenomenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Populations of group-living species comprise individuals who differ in the level of interaction they have with others1,2. These interactions occur non-randomly and often result in lasting and stable social bonds, also called friendships3, that can improve individual fitness4. For example, offspring survival is higher in social female yellow baboons5 and in feral horses with more and stronger female-male bonds6. Similarly, in marmosets, breeding pairs and breeder-helper dyads with stronger bonds contributed more in offspring care7. In bottlenose dolphins, strong bonds between males increased mating chance8, while male-female bonding increased the lifespan of juvenile males9. Spotted hyenas10, chimpanzees11 and also humans12 engage in more cooperative interactions with friends. Often age, sex, kinship or rank similarity are used to explain variation in the strength of social bonds5,13,14,15. However, the influence of these factors is very inconsistent across studies and often species-specific. For example, in chimpanzees strong social bonds are typically formed between related dyads and individuals of similar age, but are also found between unrelated non-age-mates16,17,18. Social living animals tend to associate with similar individuals19,20,21,22, a phenomenon called homophily23. In humans homophily has been found across many phenotypic dimensions like sex, age and class23,24,25 but also personality26,27,28. Recently, homophily in personality has been studied as an important factor contributing to the existing variability in social relationships across a range of phylogenetically distant taxa. For example, similarity in exploratory behavior influenced assortment in female zebra finches29 and male great tits30, similarity in Boldness predicted bonding in baboons20 and Sociability scores predicted relationship quality in chimpanzees21 and capuchin monkeys31.

While several studies have used relatively simple measures to assess relationship quality, including only one or just a few behaviors like agonistic support32, proximity21,30 or time spent in proximity and grooming20,33,34, a more inclusive way of determining relationship quality is to use composite measures. Cords and Aureli35 introduced a composite model to measure relationship quality consisting of following three components: value, compatibility and security. The value of a relationship comprises the benefits that result from that relationship like food sharing or agonistic support. The compatibility between two partners is a measure of the level of tolerance between individuals, and reflects the general nature of social interactions in a dyad. This means that in dyads with frequent aggressive interactions and counter-interventions, the nature of the relationship is defined as less tolerant. The predictability and consistency of the behavior of both partners over time describes the security of a relationship30,36,37. This three-component model has already been implemented in different study species. Relationship value contained behaviors relating to mainly social affiliation, tolerance and support in chimpanzees36,38, ravens39, Japanese macaques40, capuchin monkeys31, bonobos41 and dolphins42. Relationship compatibility contained aggressive behaviors in all but two studies40,42 and for the third component of relationship quality, security, mixed results have been found across studies31,33,34,35,37,43. Behaviors loading on this component greatly differed, making this component the least consistent across studies.

Homophily in personality seems to be widespread among different taxa, albeit in different personality traits with varying results. Studying closely related species may help in explaining these differences and in understanding how homophily in personality evolved. While homophily in personality has been studied in both humans27,28 and chimpanzees21, no studies have been done in our other close relative, the bonobo. Bonobo societies are characterized by complex social relationships, where the strongest bonds are found between females44,45,46 and between females and their adult sons45,47,48,49. A previous study on bonobos41 found that relationship value was highest between unrelated female-female dyads and related male-female dyads. Relationship compatibility was highest between female-female dyads and between bonobos with large rank distances. However, not all variability in relationship quality could be explained by sex, rank, age and relatedness41. In this study, we aim to investigate the potential influence of personality on dyadic relationship quality. Bonobos within the same social group exhibit remarkable individual differences in personality50,51, and bonobos may partly choose who they want to associate with based on similarity or differences in personality. We previously identified personality in bonobos using behavioral observations, and found four personality traits: Sociability, Boldness, Openness and Activity52. Here, we aim to find how similarity in each of the four personality traits impacts dyadic relationship quality in bonobos. Based on previous findings in chimpanzees and capuchin monkeys31 we expect to find a link between similarity in Sociability and relationship value. Our study will be the first to use the composite measure for different aspects of relationship quality to report on the potential role of personality similarity on relationship compatibility.

Results

Relationship quality

Eight dyadic behavioral variables were included in the first exploratory factor analysis. Sampling adequacy was high (KMO = 0.652) and inter-variable correlations were sufficiently high (Bartlett’s test of sphericity: chisq = 275.284, df = 15, p < 0.001). Initial exploration using factor analysis revealed a three-component solution. However only one item, grooming symmetry, loaded on the third dimension, and therefore a new factor analysis was conducted53 maintaining only two factors. Next, grooming symmetry and aggression symmetry were excluded from the EFA based on low factor loadings (Table 1). Varimax- and promax-rotated dimensions did not differ substantially.

The first factor explained 36% of the total variance and had positive loadings for proximity, grooming frequency, peering, and support. This component is very similar to the relationship value component of previous studies, and included traits related to fitness such as coalitionary support35,36,41 and was thus labelled “value”. The second component explained 14% of the total variance and had positive loadings for counter-intervention and aggression frequency and thus was similar to the second component found by previous studies36,41, “relationship incompatibility”. To make this factor easier for further interpretation, we reversed the signs for this component and relabeled it “compatibility”36,41.

The influence of genetic sex combination and similarity in personality on relationship quality

Relationship value

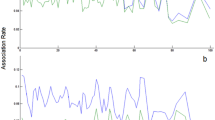

Overall, the set of predictors significantly influenced relationship value (χ2 = 24.8, df = 7, p = 0.001). More specifically, relationship value differed substantially between the genetic sex combinations (χ2 = 15.8, df = 3, p = 0.001) (Fig. 1a), such that mother-son dyads had the highest relationship value (mean ± SD = 1.50 ± 0.88), followed by female-female dyads (mean ± SD = 0.40 ± 0.78), unrelated female-male dyads (mean ± SD = −0.33 ± 0.92), and male-male dyads (mean ± SD = −0.41 ± 0.89).

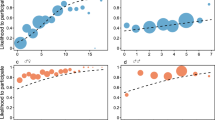

Besides genetic sex combination, similarity in Sociability was also significantly, tough less apparent, associated with relationship value (χ2 = 4.1, df = 1, p = 0.042; Fig. 2a), with subjects having more similar Sociability scores exhibiting higher value relationships (estimate ± SD = −0.26 ± 0.09). The other personality traits did not significantly influence relationship value (all p > 0.05) (Table 2, Fig. 2). Data simulations showed that large and medium-large estimates will be detected in this model with a probability of 1 and 0.80, respectively, indicating high power. The probability of detecting small effects was 0.49, indicating intermediate power. Type 1 error rates were within reasonable boundaries (0.067 and 0.083 for the two 0-value estimates; see Supplementary Materials).

Relationship compatibility

Overall, the set of predictors significantly influenced relationship compatibility (χ2 = 26.3, df = 7, p < 0.001). Relationship compatibility differed substantially between the genetic sex combinations (χ2 = 14.75, df = 3, p = 0.002, Fig. 1b). Mother-son dyads had the most compatible relationships (mean ± SD = 0.66 ± 0.48), followed by female-female dyads (mean ± SD = 0.64 ± 0.50) unrelated female-male dyads (mean ± SD = 0.04 ± 0.62), and male-male dyads (mean ± SD = −0.35 ± 0.63). Further, relationship compatibility was significantly associated with similarity in Activity (χ2 = 5.2, df = 1, p = 0.023; Fig. 3d): bonobos with relatively different Activity scores engaged in more compatible relationships (estimate ± SD = 0.20 ± 0.07) (Fig. 3). None of the other personality traits was associated with relationship compatibility (all p > 0.1, Table 3, Fig. 3). The data simulations showed that large and medium-large estimates will be detected in this model with a probability of 1 and 0.81, respectively, indicating high power. The probability of detecting small effects was 0.49, indicating intermediate power. Type 1 error rates were within reasonable boundaries (0.079 and 0.073 for the two 0-value estimates; see Supplementary materials).

Discussion

The general aim of this paper was to understand the role of kinship, sex and personality in shaping relationship quality of captive bonobos. Our results indicate that kinship and sex combination, as well as homophily in personality traits Sociability and Activity, affect relationship value and compatibility in bonobos.

Similar to the relationship quality model previously described41, our dimension reduction analysis revealed two components. Due to low item loadings of symmetry in affiliative behavior, the third factor, ‘relationship security’, was not retained in this study. Our first component of relationship quality, relationship value, is comparable to the first component in chimpanzees36,38, ravens39, Japanese macaques40, spider monkeys54, barbary macaques43, capuchin monkeys31, bonobos41 and dolphins42. This component was significantly influenced by genetic sex combination, with mother-son dyads showing the highest value. This is in line with bonobo socio-ecology, where mothers provide agonistic support to their (sub)adult sons against others49,55,56, enhance their mating success57,58 and show high levels of dyadic grooming49. Similarly, higher relationship values between kin were also previously described in chimpanzees36,38, ravens39, macaques40 and a previous bonobo study41. Unrelated female dyads also showed high relationship values, which is in line with higher frequencies of reciprocal support among them, even though they do not always spend more time in proximity and show lower levels of dyadic grooming49. In addition to genetic sex combination, relationship value was also significantly influenced by homophily in Sociability scores. Our Sociability dimension includes mainly affiliative behaviors (grooming frequency, density and diversity and the number of individuals). Interestingly, while bonobos with similarly high Sociability scores will need to be in proximity to behave affiliative, causing high value relationships, this homophily in Sociability effect also indicates that individuals with similarly low Sociability scores, likewise have high value relationships. Low Sociability individuals, who do not engage in many social interactions, therefore invest a lot in just a few social relations, resulting in rare, but high value relationships. Our Sociability dimension is comparable to the Sociability dimensions found in capuchin monkeys31 and chimpanzees21, where similarity in this personality trait also resulted in higher quality relationships with more dyadic affiliation31 and more contact-sitting21, respectively. The Sociability dimension most resembles the Extraversion dimension in humans59,60, who also prefer friends that are more similar in Extraversion scores27,28. We did not find homophily in any of the other personality traits for relationship value. Homophily in Openness resulted in high quality relationships in humans27,61 and capuchin monkeys31, but no such association was found in our study. Also for Boldness, we did not find any effect of similarity in Boldness on relationship value, while in chimpanzees21 and baboons20 dyads with more similar boldness scores showed more contact sitting and grooming, respectively. Chimpanzees with more similar Grooming Equity scores also showed more contact sitting, but only among non-kin21. The Grooming Equity factor in this study, however, comprised both grooming density and grooming diversity, two behaviors that were included in our Sociability factor.

Our second relationship quality component, compatibility, was also influenced by genetic sex combination. Unsurprisingly, the highest compatibility scores were found between mother-son dyads followed by unrelated female-female dyads, female-male dyads and male-male dyads. Aggression is most common between males and from females to males but rarely happens between females or from males to females55,62,63. Also in chimpanzees36,38, ravens39, macaques40 and a previous bonobo study41 higher compatibilities were found between related individuals. Relationship compatibility was also significantly influenced by personality, albeit less clear given the high spread of our data. Similarity in Activity resulted in lower compatibility scores meaning that individuals with similar Activity scores engage in more counter-interventions against each other and behave more aggressively against one another. Our Activity trait had a high positive loading for activity and a negative one for self-scratching. In addition, grooming density, and time spent in proximity to the leopard had loadings > |0.4| on Activity but were attributed to Sociability and Boldness, respectively, due to higher loadings on these factors.

In chimpanzees, activity and self-scratching loaded on two separate personality factors: Activity and Anxiety21,64. Similarity in these personality traits resulted in stronger friendships in unrelated chimpanzees21, while similar Activity levels in bonobos here result in less compatible relationships. This effect might partly be explained by an underlying sex bias in Activity scores. Additional analyses for sex effects on bonobo personality dimensions (see Supplementary materials) indicate that bonobo males score significantly higher on Activity than females. In chimpanzees, higher levels of self-directed behaviors in males, have been suggested to reflect the stress of their male dominated society64. Considering that female bonobos occupy the higher ranks65,66, our results are in line with potential dominance-related influences on personality. However, further studies are needed to confirm the link between Activity, self-scratching and rank. If these effects are present, dyads with more similar Activity scores and small rank differences would show higher dyadic frequencies of aggression and therefore have less compatible relationships. However, these effects are not linear, as shown by the high distribution of data points on the graph. Similarity in Sociability, Boldness and Openness did not influence relationship compatibility in our study.

While our bonobo personality factors, based on behavioral observations, are comparable to the personality factors in humans26,27 and chimpanzees21 different results concerning the effect of personality on friendships were found. One apparent explanation is that we implemented a different and perhaps more inclusive composite model to measure relationship quality35. In chimpanzees21, contact-sitting was used as a simple measure for friendship, while in humans, questionnaire answers were used instead of behavioral observations to determine relationship quality27. Studying the influence of personality on the composite measure for relationship quality in chimpanzees36 might be an interesting next step to further our understanding of the evolution of homophily in friendships in these two closely related species.

While the relationship between personality and friendship is clear in several species, less is known about its underlying mechanism. Do individuals choose others with similar personalities to form friendships or do personalities of individuals become more similar over time due to shared experiences? This attraction and/or convergence comparison31 requires a long-term study to compare personalities and relationship quality at consecutive points in time. Further, the role of personality in friendships seems to be trait-specific, as opposed to all traits being similar between friends, and the importance of different traits appears to be species-specific. Further research is therefore needed to study which benefits result from similarity in certain personality traits and whether the evolutionary fitness of dyads with similar personalities is higher than dissimilar dyads in both captive and wild populations.

In conclusion, we found that the quality of social bonds between bonobos is influenced by the genetic sex combination of both partners and their personality similarity, more specifically in Sociability and Activity. Homophily in Sociability is likely to be a shared feature in ourselves and our closest relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos. While similarity in Sociability might promote reliable high quality relationships through reciprocity in similarly affective behavioral tendencies, lower compatibility levels of dyads with more similar Activity scores may be a byproduct of rank differences.

Methods

Behavioral data were collected for captive bonobos housed in six zoological parks: Planckendael (PL) in Mechelen, Belgium; Apenheul (AP) in Apeldoorn, the Netherlands; Twycross Zoo World Primate Centre (TW), Twycross, United Kingdom; Wuppertal Zoo (WU), Wuppertal, Germany; Frankfurt Zoo (FR), Frankfurt, Germany; and Wilhelma Zoological and Botanical Garden (WI) in Stuttgart, Germany. The subjects included 23 female and 16 male bonobos whose ages ranged from 7 to 63 years. All subjects were housed in groups that included juveniles and/or infants, which were excluded from the behavioral data collection. Behavioral data for relationship quality and personality analysis were collected during the same observational periods. Details on group composition and data collection can be found in the Supplementary Table S1.

Measures and analysis

We collected a total of 1442.39 hours of focal observations (mean 16.37 hours per individual), 43506 group scans (mean 545 per individual) and 430.96 h of all occurrence observations during feedings (mean 28.73 hours per group). Inter-observer reliabilities reached a mean of r = 0.87 across all observers, meaning that all observations were highly reliable67. Live scoring of behavioral data was done using The Observer (Noldus version XT 10, the Netherlands).

Personality profiles

Individual personality profiles were available and based on the personality model described in a previous paper52. The behavioral variables used to construct this model were derived from both naturalistic and experimental settings52,68. In short, we included a total of 17 behavioral variables (10 from the naturalistic context and 7 from the experimental contexts). Raw variables were standardized into z-scores for each group before combining data from different zoos. As the definition of personality requires stability of traits between individuals across time, data were collected in two consecutive years for each group allowing us to test for temporal consistency. Intraclass correlations were used to determine temporal stability and only variables that were stable were used to determine personality structure. Dimension reduction analysis on these variables revealed four factors: Sociability, Boldness, Openness and Activity52. Details of each item’s loading onto each dimension are shown in Table 4 (See also Supplementary Table S3). Items that showed cross-loadings > |0.4| on multiple components, were considered part of the dimension on which they had the highest loading.

Relationship quality

Measures for relationship quality were determined based on the relationship quality model described in a previous paper on bonobos41. We extracted dyadic scores for 8 social behavioral variables, which were collected in a naturalistic setting: Aggression frequency, aggression symmetry, counter-intervention, grooming frequency, grooming symmetry, peering frequency, proximity, support (For definitions see: Supplementary Table S2). We then performed exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization to extract composite measures for these 8 variables. The number of dimensions to extract was determined by inspecting the scree plot and by conducting a parallel analysis69,70. The factors were then subjected to a varimax rotation and variable loadings ≥ |0.4| were interpreted as salient.

Linear mixed models

To determine potential associations between relatedness, sex combination, personality profiles and relationship quality measures, we used General Linear Mixed Models with Gaussian error distribution and identity link function (lme4 package 1.1-1371) for a total of 90 dyads. Rank difference was not included in our models to reduce the amount of overfitting. Similarity in personality per dyad was determined taking the absolute difference of the personality scores of both individuals of a dyad. The relationship quality components were treated as response variables in two different models. The full models comprised the different personality similarity variables (all z-transformed) and the fixed categorical variable “genetic sex combination” (denoting the demographic nature of the dyad: female-female, female-male, male-male, mother-daughter, mother-son) as predictor variables. Combining relatedness and sex combination in one factor (genetic sex combination) allows us to separate related female-male (mother-son dyads) from unrelated female-male dyads and compare results between them. Only one mother-daughter dyad was included in our sample and was therefore excluded from statistical analyses. The random effects structure consisted of intercepts for each of the two subjects in the dyad and for the location of observation (zoo), including the random slopes of the four personality variables within the subjects and zoo, and the additional random slopes of genetic sex combination (dummy coded) within zoo72,73. The null model was an intercept-only model, with the same random effects structure as the full model. Given the high number of estimated parameters in relation to the sample sizes (i.e., slight overfitting), we performed simulations to assess the power of our models. Data were corrected for observation time and diagnostic plots (residuals vs. fitted, QQ plots) were used to confirm the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances. When any of the assumptions were not met, we used square root, z- or log transformations of our variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 and R (version 3.4.3; R Core Team, 2017).

Ethical statement

No animals were sacrified or sedated for the purpose of this study. This study was approved by the Scientific Advisory Board of the Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp and the University of Antwerp (Belgium), and endorsed by the European Breeding Program for bonobos. All research complied with the ASAB guidelines74.

References

Reale, D., Dingemanse, N. J., Kazem, A. J. & Wright, J. Evolutionary and ecological approaches to the study of personality. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 365, 3937–3946 (2010).

Wolf, M. & Weissing, F. J. An explanatory framework for adaptive personality differences. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 365, 3959–3968 (2010).

Silk, J. B. Using the ‘F’-Word in Primatology. Behaviour 139, 421–446 (2002).

Hinde, R. A. Interactions, Relationships and Social. Structure. Man 11, 1–17 (1976).

Silk, J. B., Alberts, S. C. & Altmann, J. Social bonds of female baboons enhance infant survival. Science 302, 1231–1234 (2003).

Cameron, E. Z., Setsaas, T. H. & Linklater, W. L. Social bonds between unrelated females increase reproductive success in feral horses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13850–13853 (2009).

Finkenwirth, C. & Burkart, J. M. Why help? Relationship quality, not strategic grooming predicts infant-care in group-living marmosets. Physiol. Behav. 193, 108–116 (2018).

Connor, R. C. & Krützen, M. Male dolphin alliances in Shark Bay: changing perspectives in a 30-year study. Animal Behaviour 103, 223–235 (2015).

Stanton, A. M. & Mann, J. Early Social Networks Predict Survival in Wild Bottlenose Dolphins. PLoS One 7, 1–6 (2012).

Drea, C. M. & Carter, A. N. Cooperative problem solving in a social carnivore. Animal Behaviour 78, 967–977 (2009).

Melis, A. P., Hare, B. & Tomasello, M. Engineering cooperation in chimpanzees: tolerance constraints on cooperation. Animal Behaviour 72, 275–286 (2006).

Majolo, B. et al. Human friendship favours cooperation in the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma. Behaviour 143, 1383–1395 (2006).

Silk, J. B., Alberts, S. C. & Altmann, J. Social relationships among adult female baboons (Papio cynocephalus) II. Variation in the quality and stability of social bonds. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 61, 197–204 (2006).

MacCormick, H. A. et al. Male and female aggression: lessons from sex, rank, age, and injury in olive baboons. Behavioral Ecology 23, 684–691 (2012).

Sosa, S. The Influence of Gender, Age, Matriline and Hierarchical Rank on Individual Social Position, Role and Interactional Patterns in Macaca sylvanus at ‘La Foret des Singes’: A Multilevel Social Network Approach. Front. Psychol. 7, 529 (2016).

Wittig, R. M. & Boesch, C. “Decision-making” in conflicts of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): an extension of the Relational Model. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 54, 491–504 (2003).

Langergraber, K., Mitani, J. & Vigilant, L. Kinship and social bonds in female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am. J. Primatol. 71, 840–851 (2009).

Mitani, J. C. Cooperation and competition in chimpanzees: Current understanding and future challenges. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 18, 215–227 (2009).

Bouskila, A. et al. Similarity in sex and reproductive state, but not relatedness, influence the strength of association in the social network of feral horses in the Blauwe Kamer Nature Reserve. Israel. Journal of Ecology & Evolution 61, 106–113 (2016).

Carter, A. J., Lee, A. E., Marshall, H. H., Tico, M. T. & Cowlishaw, G. Phenotypic assortment in wild primate networks: implications for the dissemination of information. R. Soc. Open. Sci. 2, 140444 (2015).

Massen, J. J. M. & Koski, S. E. Chimps of a feather sit together: chimpanzee friendships are based on homophily in personality. Evolution and Human Behavior 35, 1–8 (2014).

de Waal, F. B. M. & Luttrell, L. M. The Similarity Principle Underlying Social Bonding among Female Rhesus Monkeys. Folia Primatologica 46, 215–234 (1986).

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L. & Cook, J. M. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology 27, 415–444 (2001).

Shrum, W., Hunter, S. M. & Cheek, N. H. Friendship in School: Gender and Racial Homophily. Sociology of Education 61, 227–239 (1988).

Moody, J. The structure of a social science collaboration network: Disciplinary cohesion from 1963 to 1999. American Sociological Review 69, 213–238 (2004).

Izard, C. E. Personality Similarity and Friendship. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 61, 47–51 (1960).

Selfhout, M. et al. Emerging late adolescent friendship networks and Big Five personality traits: a social network approach. J. Pers. 78, 509–538 (2010).

Nelson, P. A., Thorne, A. & Shapiro, L. A. I’m outgoing and she’s reserved: the reciprocal dynamics of personality in close friendships in young adulthood. J. Pers. 79, 1113–1147 (2011).

Schuett, W., Godin, J.-G. J. & Dall, S. R. X. Do Female Zebra Finches, Taeniopygia guttata, Choose Their Mates Based on Their ‘Personality’? Ethology 117, 908–917 (2011).

Aplin, L. M. et al. Individual personalities predict social behaviour in wild networks of great tits (Parus major). Ecol. Lett. 16, 1365–1372 (2013).

Morton, F. B., Weiss, A., Buchanan-Smith, H. M. & Lee, P. C. Capuchin monkeys with similar personalities have higher-quality relationships independent of age, sex, kinship and rank. Animal Behaviour 105, 163–171 (2015).

Cooper, M. A., Berntein, I. S. & Hemelrijk, C. K. Reconciliation and relationship quality in Assamese macaques (Macaca assamensis). Am. J. Primatol. 65, 269–282 (2005).

Seyfarth, R. M., Silk, J. B. & Cheney, D. L. Social bonds in female baboons: the interaction between personality, kinship and rank. Animal Behaviour 87, 23–29 (2014).

Stadele, V. et al. Male-female relationships in olive baboons (Papio anubis): Parenting or mating effort? J. Hum. Evol. 127, 81–92 (2019).

Cords, M. & Aureli, F. Reconciliation and relationship qualities. in Natural Conflict Resolution (eds de Waal, F. B. & Aureli, F.) Ch. 9, 177–198 (University of California Press, 2000).

Fraser, O. N., Schino, G. & Aureli, F. Components of Relationship Quality in Chimpanzees. Ethology 114, 834–843 (2008).

Massen, J., de Vos, H. & Sterck, E. Close social associations in animals and humans: functions and mechanisms of friendship. Behaviour 147, 1379–1412 (2010).

Koski, S. E., de Vries, H., van de Kraats, A. & Sterck, E. H. M. Stability and change of social relationship quality in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). International Journal of Primatology 33, 905–921 (2012).

Fraser, O. N. & Bugnyar, T. The quality of social relationships in ravens. Animal Behaviour 79, 927–933 (2010).

Majolo, B., Ventura, R. & Schino, G. Asymmetry and dimensions of relationship quality in the japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata yakui). International Journal of Primatology 31, 736–750 (2010).

Stevens, J. M. G., de Groot, E. & Staes, N. Relationship quality in captive bonobo groups. Behaviour 152, 259–283 (2015).

Moreno, K. R., Highfill, L. & Kuczaj, S. A. Does personality similarity in bottlenose dolphin pairs influence dyadic bond characteristics? International Journal of Comparative Psychology 30, 1–15 (2017).

McFarland, R. & Majolo, B. Exploring the components, asymmetry and distribution of relationship quality in wild barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus). PLoS One 6, e28826 (2011).

White, F. J. Party composition and dynamics in Pan paniscus. International Journal of Primatology 9, 179–193 (1988).

Furuichi, T. Social interactions and the life history of female Pan paniscus in wamba, zaire. International Journal of Primatology 10, 173–197 (1989).

Parish, A. R. Sex and food control in the “uncommon chimpanzee”: how bonobo females overcome a phylogenetic legacy of male dominance. Ethology and Sociobiology 15, 157–179 (1994).

Fruth, B., Hohmann, G. & McGrew, W. The pan species. In The nonhuman primates (eds. Dolhinow, P. & Fuentes, A.) 64–72 (Mayfield, 1999).

Hohmann, G. Social bonds and genetic ties: kinship, association and affiliation in a community of bonobos (Pan paniscus). Behaviour 136, 1219–1235 (1999).

Stevens, J. M., Vervaecke, H., De Vries, H. & Van Elsacker, L. Social structures in Pan paniscus: testing the female bonding hypothesis. Primates 47, 210–217 (2006).

Weiss, A. et al. Personality in bonobos. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1430–1439 (2015).

Garai, C., Weiss, A., Arnaud, C. & Furuichi, T. Personality in wild bonobos (Pan paniscus). Am. J. Primatol. 78, 1178–1189 (2016).

Staes, N. et al. Bonobo personality traits are heritable and associated with vasopressin receptor gene 1a variation. Sci. Rep. 6 (2016).

Budaev, S. V. Using principal components and factor analysis in animal behaviour research: caveats and guidelines. Ethology 116, 472–480 (2010).

Rebecchini, L., Schaffner, C. M. & Aureli, F. Risk is a component of social relationships in spider monkeys. Ethology 117, 691–699 (2011).

Kano, T. The last ape: pygmy chimpanzee behavior and ecology. (Stanford University Press, 1992).

Furuichi, T. Female contributions to the peaceful nature of bonobo society. Evol. Anthropol. 20, 131–142 (2011).

Surbeck, M., Mundry, R. & Hohmann, G. Mothers matter! Maternal support, dominance status and mating success in male bonobos (Pan paniscus). Proc. Biol. Sci. 278, 590–598 (2010).

Surbeck, M. et al. Males with a mother living in their group have higher paternity success in bonobos but not chimpanzees. Curr. Biol. 29, R354–R355 (2019).

McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Reinterpreting the myers-briggs type indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. J. Pers. 57, 17–40 (1989).

Watson, D. & Clark, L. A. Extraversion and its positive emotional core. in Handbook of Personality Psychology 767–793 (CA: Academic Press, 1997).

Holland, J. L., Johnston, J. A., Hughey, K. F. & Asama, N. F. Some explorations of a theory of careers VII. A replication and some possible extensions. Journal of Career Development 18, 91–100 (1991).

Hohmann, G. & Fruth, B. Intra- en inter-sexual aggression by bonobos in the context of mating. Behaviour 140, 1389–1413 (2003).

Surbeck, M., Deschner, T., Schubert, G., Weltring, A. & Hohmann, G. Mate competition, testosterone and intersexual relationships in bonobos, Pan paniscus. Animal Behaviour 83, 659–669 (2012).

Koski, S. E. Social personality traits in chimpanzees: temporal stability and structure of behaviourally assessed personality traits in three captive populations. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 2161–2174 (2011).

Stevens, J. M. G., Vervaecke, H., de Vries, H. & van Elsacker, L. Sex differences in the steepness of dominance hierarchies in captive bonobo groups. International Journal of Primatology 28, 1417–1430 (2007).

Vervaecke, H., De Vries, H. & Van Elsackar, L. Dominance and its behavioral measures in a captive group of bonobos (Pan paniscus). International Journal of Primatology 21, 47–68 (2000).

Martin, P. R. & Bateson, P. P. G. Measuring behaviour: an introductory guide. 6 edn, (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Staes, N., Eens, M., Weiss, A. & Stevens, J. M. G. Mind and brains compared. in Bonobos: unique in mind, brain and behavior (ed. Hare, B.) 183–198 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Horn, J. L. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrica 30, 179–185 (1965).

O’Connor, B. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAPtest. Behav. Res. Methods 32, 396–402 (2000).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67, 1–48 (2015).

Barr, D. J., Levy, R., Scheepers, C. & Tily, H. J. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: keep it maximal. J. Mem. Lang. 68 (2013).

Schielzeth, H. & Forstmeier, W. Conclusions beyond support: overconfident estimates in mixed models. Behav. Ecol. 20, 416–420 (2009).

ASAB. Guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioural research and teaching. Animal Behaviour 83, 301–309 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible through financial support from FWO Flanders. We are grateful to the director and staff of the Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp (RZSA) for their support in this study and the staff of the Centre for Research and Conservation (CRC) for the interesting suggestions and discussions. The CRC receives structural support from the Flemish Government. We thank all students involved in data collection: Adriana Solis (University of Groningen), Annemieke Podt, Sanne Roelofs, Wiebe Rinsma, Linda Jaasma, Marloes Borger, Melissa Vanderheyden and Martina Wildenburg (University of Utrecht). We also thank Roger Mundry for statistical advice. Special thanks go to all the zoological institutes who hosted us during behavioral data collection: Planckendael (Mechelen, Belgium), Apenheul (Apeldoorn, the Netherlands), Twycross Zoo World Primate Centre (Twycross, United Kingdom), Wuppertal Zoo (Wuppertal; Germany), Frankfurt Zoo (Frankfurt, Germany) and Wilhelma zoological and botanical garden (Stuttgart, Germany).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.V., N.S., M.E. and J.S developed the study. J.V. and N.S. were in charge of behavioral data collection. J.V., N.S. and E.J.C.v.L. performed statistical analyses. J.V. and N.S. wrote the manuscript with editing from all coauthors involved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verspeek, J., Staes, N., Leeuwen, E.J.C.v. et al. Bonobo personality predicts friendship. Sci Rep 9, 19245 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55884-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55884-3

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.