Abstract

4D-printed materials are an emerging field of research because the physical structure of these novel materials respond to environmental changes. 3D printing techniques have been employed to print a base material with shape memory properties. Geometrical deformations can be observed once an external stimulus triggers the shape memory effect (SME) integrated into the material. The plasticizing effect is a well-known phenomenon where the microscopic polymer chain movements have been altered and reflected in different shape memory behaviour. It has been suggested that a 4D material with localized actuation behaviour can be fabricated by utilizing functionally graded layers made from different degrees of plasticizing. This study demonstrated that a novel 4D material can be fabricated from material extraction continuous printing technique with different loadings of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) plasticize, achieving localized thermal recovery. The results indicate that a plasticized functional layer is an effective technique for creating next generation 4D materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive manufacturing, also known as three-dimensional (3D) printing, is an emerging fabrication technique for creating complex 3D objects by utilizing a layer-by-layer deposition method1,2,3. In the past decade, a number of different 3D printing technologies have been proposed and developed in both academia and industry. For example, fused deposition modelling (FDM) extrudes molten polymer4,5, binder jetting deposits adhesive agents onto powder materials6,7, and stereolithography (SLA) uses the photopolymerization technique to cure and solidify liquid polymer resin8,9,10. Due to the variety of available printing technologies, additive manufacturing applications include rapid physical prototype fabrications11,12,13, biological and healthcare products14,15, functional electronic device fabrications16,17, and honeycomb structures18.

Advances in novel material development have increased the number of materials that can employ additive manufacturing, particularly 3D-printed composites and customized materials19,20. These application-driven composite materials may have superior mechanical19, thermal21, and electrical properties22 and can be fabricated into complex geometries. Smart materials in 3D printing also draw significant attention for their ability to respond to external stimuli23,24,25. Temperature26,27, water28,29, and light30,31 are potential stimuli that can cause shape memory polymers (SMPs) to recover to a pre-defined shape after plastic deformation. Because the geometry in smart material-based 3D-printed components can change over time, a new term, “4D printing,” was established11,23,24,25,32. Compared to traditional 3D-printed parts, the additional dimension in the time domain allow for the components to undergo dramatic changes in shape when subjected to an external stimulus. Similar to SMPs, stimuli that induce time-dependent behaviours are usually temperature changes33,34,35 or water exposure11,36,37.

Four major building blocks for 4D printing development have been identified and are shown in Fig. 1. These include (1) a proper 3D printing facility/platform with a pre-determined printing path, (2) a suitable smart or stimulus-responsive material, (3) an external stimulus for activation, and (4) a known activation/interaction mechanism, such as a shape memory effect (SME)24. These building blocks are interconnected such that they function together to create an effective 4D material. The type of printer platform depends heavily on the materials used, and these materials may only respond to certain stimuli. In addition, the macroscopic shape memory behaviour depends not only on the material properties, but also on the fabrication process parameters, such as printing direction and composite layout. As a result, all four components must be carefully considered during 4D printing development.

4D-printed components can be created through a number of different methods. The polyjet printer system dispenses photocurable SMP using a bottom-up method that cures each layer separately11,32,38. This is similar to the direct-writing methods proposed by Lewis et al.36,39,40. In comparison, SLA printers directly cure liquid polymer resin and can also be used in 4D printing applications16,41.

Conventionally, 4D printing involves printing from mono material resin. In 2013, Ge et al. provided one of the earliest reports of the fabrication of 4D-printed active composites (PACs) by utilizing fiber/matrix configurations38. The group deposited shape memory polymer fibers within a UV-curable elastomer matrix. The fibers exhibited SME between 15 °C to 60 °C, and the matrix underwent a glass transition (Tg) below –5 °C. Thus, the thermomechanical properties of the elastomer do not influence the shape-shifting behaviour of the fibers during the recovery process. When changing the PAC into a temporary shape, mechanical deformation must be applied at a high temperature after printing. Reheating the deformed PAC can change the PAC back to its printed shape. In addition to the conventional shape memory behaviour, the group also demonstrated that anisotropy behaviour can be achieved through fiber alignment using a laminated structure.

Despite the widespread availability of FDM printers on the market, there are relatively few studies that have focused on FDM methods for creating 4D materials42. Recently, Ly et al. demonstrated that 4D objects can be obtained from directly printing SMP material43. It is possible to achieve electroactive ability in SMP materials by blending multiwalled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) into the thermoplastic system. Similarly, Hu et al. established the self-bending ability of FDM-printed SMP and constructed a constitutive model for its recovery behaviour44. Bodaghi et al. used polyurethane-based SMP filaments to create FDM-printed 4D SMP metamaterial45,46. The team also attempted to create a functionally graded (FG) layer by varying the printing conditions46.

Recent 4D printing studies have shown the capabilities of an FDM-printed sample; nevertheless, the SMP materials used in these studies were directly purchased from the market and were not custom-formulated. It is proposed that optimized 4D performance and recovery can be achieved by redesigning the material properties from microscale crystalline/amorphous structures to macroscale 3D-printed layers. For example, the term FG layer used in46 provides interesting insight into next-generation 4D materials despite the lack of material property characterization tests on the different functional layers. In the literature, FG materials are defined as composites with gradual property variation throughout the object47,48. Due to the anisotropic design, properties such as specific crack propagation49 and superior electrical conductivity can be achieved50. The FG material concept can also be implemented in SMP composites. For instance, DiOrio et al. created a thermoset SMP with multiple layers, and each had a different transitional temperature51. Lu et al. created different FG layers of carbon nanofiber (CNF) and boron nitride (BN) nanopaper onto a SMP to achieve electroactive ability52.

Printing technologies further simplify the fabrication of functionally graded material (FGM). It is possible to achieve multi-shape or revisable SMP through 4D printing due to the designated differences in each functional layer33,53. Although these 3D-printed FGM have shown interesting properties and performance, the functional layers are still constructed from a single base material rather than composites. For instance46, simply varied printing parameters, such as the speed and temperature of each FG layer. A plasticizer can be used alongside the base material to further develop 4D-printable FGM. Polylactic acid (PLA) is one of the most commonly used materials in FDM due to its low cost and high stiffness54. Furthermore, the plasticizing effect of PLA and the thermal/rheological/mechanical properties that are induced as a result are well-documented55,56,57,58,59. Moreover, several groups have reported the SME of 3D-printed PLA60,61,62,63. In our previous study, we also demonstrated that the plasticized SMP may have superior recovery properties64. This study showed that it is possible to create a 4D FDM-printed multi-shape memory composite with localized actuation properties by implementing the plasticizing effect. A tri-layer FG 4D composite with increasing plasticizer content across the gradient was fabricated. PLA was first plasticized with different amounts of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) to alter the mechanical and thermal properties at the microscopic level. Due to changes in the polymeric chain movements, the macroscopic SME could be controlled by 4D printing different FG layers to achieve multi-shape memory and localized actuation properties.

Results and Discussion

Plasticizer-induced microscopic morphological changes

It was expected that the microstructure of the PLA matrix would be altered due to the presence of PEG plasticizer. In Figs 2a,d, it can be inferred that the material has a brittle fracture behaviour because of the sharp surface defects. With an increasing PEG content, the sharp edges begin to smoothen as the mechanical ductility of the material improves55,56. Increasing surface roughness and fibril structures can also be observed, which is similar to the results reported in literature55. To further verify the effect of FDM printing on the material, the 3D-printed components were subjected to liquid nitrogen fracture, and the morphologies are shown in Fig. 3. All three materials were printed successfully as clear extruded polymer filament layers can be observed. The cross-sections of the extruded layer (Fig. 3d–f) also show similar fracture characteristics when compared to those of the pre-extruded composites (Fig. 2). Brittle fracture edges are suppressed and replaced by fibril-like structures due to the induced plasticizing effect of PEG. In addition to the cross-sectional surface, the ductile behaviour can also be observed on the exterior surface layer under high PEG content as shown in Fig. 3c,f.

Chemical composition verification

The FTIR spectra of PLA with different PEG contents are shown in Fig. 4. For PLA, the C=O group was represented by a characteristic peak at 1750 cm−1 65,66, and was only present in samples containing PLA. Three different peaks characteristic of PEG were at 843 cm−1, 947 cm−1, and 1280 cm−1 67,68. These peaks were relatively weak when PEG content was low (10 wt%) and could only be identified when PEG content was increased to 30 wt%.

Thermal behaviour of plasticized PLA composites

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments and thermal thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) were conducted to analyze the thermal behavior (Fig. 5). Table 1 summarizes the glass transition (Tg), cold crystallization (Tcc), melting temperature (Tm), cold crystallization enthalpy (ΔHcc), melting enthalpy (ΔHm), and percent crystallinity (Xc). Table 2 summarizes the initial degradation (Ti), primary maximum weight loss slope (Ti max, 1), and secondary maximum weight loss slope (Ti max, 2) from the TGA/DTG curves. The percent crystallinity was calculated by subtracting the ΔHcc from the ΔHm then dividing by the ΔHm of a perfect crystal (197 J/g for PEG and 93.6J/g for PLA)69,70.

One of the most noticeable changes caused by the plasticizing effect was the decrease in Tg (Fig. 5a and Table 1). Because the PEG molecules are much smaller than the PLA polymeric chains, the plasticizer can easily penetrate the PLA matrix and enhance polymeric chain movement, thus lowering the Tg71,72. At 30 wt% PEG, the Tg of PLA could no longer be observed since the melting behaviour of PEG was dominant in the same temperature region71. The presence of PEG also enhanced PLA formation and was observed as an increase in melt enthalpy. It is possible that the plasticizer molecules lowered the interfacial surface energy and promoted PLA crystal nucleation71,73.

To verify the observed thermal stability and processability, a heat-and-hold experiment was conducted on PEG at 180 °C (Fig. 5b). The material was thermally stable for a period of 35 min as the overall weight lost was less than 0.5%. Based on the TGA curves (Fig. 5c), no material residue was left after thermal degradation above 500 °C as complete decomposition behaviour was observed. Both Ti and Ti max were lowered once the plasticizer was incorporated into the PLA matrix due to the enhanced PLA/PEG interaction. With 30 wt% PEG, a two-step degradation behaviour resulted from the high PEG content. Figure 5d shows that the peaks for the Ti max 2 of the 30PEG curve closely matched the DTG curve of pure PEG. This result suggests that PEG crystalline formation may have occurred within the composites, and a continuous phase was no longer present in the PLA/PEG composites.

Viscoelastic and rheological characterizations

To characterize the viscoelastic behaviour of the composite, dynamic mechanical tests were conducted under two conditions: a room temperature frequency sweep (Fig. 6a) and a single-frequency temperature sweep (Fig. 6b). Both the storage modulus and tan Delta values were affected by the frequency at room temperature. A slight increase in the storage modulus of the 10PEG sample may contribute to the higher crystallinity as shown in the thermal analysis. With 30% PEG, the storage modulus dropped significantly because of the plasticizing effect in the PLA matrix. In Fig. 6b, the storage modulus displayed temperature-dependent behaviour. With increasing PEG content, the tan Delta peak shifted to a lower temperature, which was represented as a decrease in Tg71.

The plasticizer effect was also monitored in rheological studies (Fig. 6c–d). At a high temperature (190 °C), the storage modulus of PLA increased with frequency. The increase in the amount of PEG present in the matrix caused the slope to decline, which suggests that the viscoelastic behaviour deviated from a typical homogeneous polymer. The data suggest that the plasticizing effect resulted in a significant reduction in the viscosity because the polymer chain movements increased as a result of the presence of PEG (Fig. 6d)64,72.

Temperature dependant mechanical properties

The stress-strain behaviour of the fabricated PLA and plasticized composite is shown in Fig. 7. The mechanical properties, including the elastic modulus, ultimate yield strength, and elongation at break, are also summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. Without any modifications, PLA exhibited a brittle behaviour with extremely low elongation at break as reported in literature60,74. The increasing plasticizing content caused a decrease in tensile strength and an increase in elongation at break74,75. Pillin et al. reported that up to 200% strain can be reached when 20 wt% of PEG with 1000 molecular weight was blended with PLA. The further addition of PEG may result in a decrease in the tensile strain because of an increase in the immiscibility75. In this study, the 30 wt% PEG/PLA blend reached a strain of over 250% before tearing under room temperature conditions. Kokturk et al. provided one of the earliest reports of high temperature and stretching-induced crystallization behaviour of PLA film76. The group demonstrated that PLA can hold a stretch ratio of up to 500% at 70 °C as the stretching was performed at temperatures above the Tg of PLA. As shown in Fig. 7b, all three composites sustained a striation ratio of at least 300% and, therefore, were suitable to be tested for shape memory properties.

Characterization for tensile shape memory properties

Zhang et al. provided one of the earliest reports of the shape memory property of PLA60. The group theorized that PLA should possess SME, but it was not be observed for PLA due to high brittleness under room temperature conditions. To avoid brittle failure, the team suggested that an elastomer matrix, such as polyamide elastomer (PAE), could be used to enhance the ductility and shape recovery performance. As a result, PLA/elastomer blends became one of the most popular choices for creating a polymeric blend SMP77,78. The fabricated composite samples withstood superior tensile strain by up to 500% in the 70 °C environment (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the high stretchability allowed for the composites to withstand the shape memory cycles tests (Fig. 8a). To characterize the shape memory properties, two performance parameters, shape recovery ratio (Rr) and shape fixing ratio (Rf), are defined by the following two equations:

where εm is the applied strain, εp is the strain after the recovery, and εu is the strain after cooling and shape-fixing.

(a) 3D shape memory cycle of different PLA/PEG composites: (1) tensile elongation at 70 °C, (2) cooling back to room temperature while maintaining stress, (3) stress release, and (4) reheating and shape recovery; (b) recovery behaviour of step 4; (c) shape recovery ratio (Rr) and shape fixing ratio (Rf) of different PLA/PEG composites.

Samples were first stretched to 200% strain in a 70 °C environment. Afterward, the temperature was lowered back to room temperature and slowly heated to 100 °C to observe recovery behaviour. The high temperature stress-strain curves showed similar dynamics as the results in Fig. 7. A sharp ultimate tensile stress peak was present for pure PLA, while 10PEG plateaued at a higher stress value compared to the 30PEG sample.

All samples achieved high shape fixity properties (close to 100%) as no elastomer matrix was present in the matrix (Fig. 8a). This was responsible for the relatively lower recovery ratio. The unmodified PLA achieved a maximum Rr value close to 50%, which was similar to the findings reported by77. It is known that the elastomer matrix is responsible for the recovery process in a polymeric blend SMP by providing elastic recovery at high temperatures77,79. Without the elastomer, the crystalline phase in PLA simply softens, and only partial recovery can be observed in the amorphous PLA phase. According to the results of the thermal analysis, the plasticizer lowered the Tg of the PLA, which suggested that a decrease in initial recovery temperature can be observed. Additionally, the initial recovery temperature of PLA was higher than 70 °C (Fig. 8b). With 10% PEG, the temperature dropped to around 60 °C, while the 30% PEG sample had a low activation temperature below 40 °C because the plasticizing effect was initiated by PEG.

Despite the fact that actuation can be trigged at a lower temperature by the plasticizer, the plasticizer had a negative influence on the recovery ratio (Fig. 8b,c. An increasing trend in ΔHm was detected by DSC after the incorporation of PEG. Due to the lower interfacial energy at the PEG/PLA region, more PLA crystal nucleation sites were available. The increase in nucleation sites allowed for the PLA crystals to be uniformly distributed within the matrix, which may have separated the amorphous regions in the PLA. These amorphous regions were critical for shape recovery to take place. Therefore, a decrease in the recovery ratio can be expected.

Interestingly, by further increasing the PEG content from 10 to 30 wt%, an improvement in shape recovery can be observed. Such behaviour may be explained by the re-distribution of the amorphous PLA phase due to the excess PEG. In order to achieve the best shape memory performance, it is critical that an optimized crystalline/amorphous phase ratio and distribution is established. With the incorporation of PEG, PLA crystals are able to nucleate at the PEG/PLA interfaces. As a result, an increase in ΔHm can be expected, as shown in Table 1. It should also be noted that the melting enthalpies of the 10PEG and 30PEG are very close to each other, which indicates that the PLA crystal content within the 10PEG is almost saturated and further increasing the PEG will not result in further PLA crystal formation. As a result, the addition PEG will only affect the PLA crystal distribution. In the 10PEG sample, the introduction of PEG separated the amorphous regions that are responsible for the shape recovery, thus a decrease in shape recovery performance can be observed. By further increasing the PEG to 30 wt% the amorphous PLA phases are merged back together, thus a slight improvement in shape recovery was observed.”

Plasticized 4D materials and their recovery behaviours

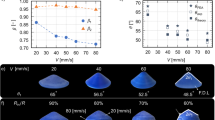

To demonstrate the shape memory behaviour, arc samples are designed. The shape memory mechanism is shown Fig. 9. An arc-shape configuration was printed to demonstrate the 4D thermal recovery ability of the fabricated sample (Fig. 10a). Detailed dimensions of the printed model can be found in the Supplementary Materials. The samples needed to be programmed into a temporary shape before 4D recovery could take place. This was done by compressing the arc-like component at 50 °C to prevent any possible brittle failure. The compressed sample was then cooled back to room temperature prior to removal of the applied stress for shape-fixing. The temporary shape training outcome is presented (Fig. 10b). No visible cracks or delamination was observed after the training process.

After shape-fixing, a heat gun was utilized above the component to initiate 4D thermal recovery. Videos were taken to visualize thermal recovery, while IR thermal videos were taken to measure the instantaneous temperature. The 4D recovery results for pure and plasticized components are presented (Fig. 11). Complete videos can be found in the Supplementary Materials. All three different compositions recovered to the printed arc-like shape. In addition to the 4D shape memory ability, the plasticizing effect was also observed. The images from the IR camera indicated that the pure PLA sample had an initial recovery temperature above 60 °C, 10PEG had a recovery temperature of 55 °C, and 30PEG had a recovery temperature below 55 °C. This behaviour was anticipated because PEG plasticizer lowered the overall Tg. These results indicate that the actuation temperature of the 4D materials could be fabricated by utilizing a plasticizing effect.

Functionally graded 4D material with localized recovery ability

Since the actuation temperature can be controlled by the amount of plasticizer, it is proposed that a multi-shape actuator can be created by utilizing the property of functionally graded layers. An FG-4D-printed composite fabricated by using a continuous FDM printing technique is shown (Fig. 12). The different weight percent of plasticizer in each layer was visually observable. Similar to the printed arc-like design (Fig. 10), the printed FG-4D model could also be programmed into the flat temporary shape configuration (Fig. 12c) by using the same procedure. The continuous printing process allowed the interfacial layer (PLA/10PEG and 10PEG/30PEG) to have good mechanical properties, and no delamination or cracking was observed at the interfacial region during shape programming.

The thermal recovery of the FG-4D material is presented (Fig. 13). As the temperature rose, the 30PEG layer recovered first and transferred the model into a transitional shape in which one side of the structure was arced while the other side was flat (Fig. 13b). By further increasing the temperature above the Tg of the unmodified PLA, full recovery of the model was achieved (Fig. 13d). A video of this process can be found in the Supplementary Materials. The thermal recovery behaviour observed in this study demonstrated that the transitional shape can be implemented in a 4D-printed structure by utilizing the temperature-dependent properties of the FG plasticized layer, which widens the possible industrial applications of 4D materials.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated that a 4D-printed material with tunable actuation temperatures can be fabricated using plasticized functionally graded layers. The activation temperature for the shape recovery process can be controlled because the plasticizer content influences the glass transition temperature of PLA. Thermal, viscoelastic, mechanical, and rheological tests indicated that the modified PLA maintains the capacity to be 3D-printed from an FDM printer. Shape memory properties were characterized and showed that the desired 4D recovery behaviour can be achieved. Lastly, the FG-4D material with localized actuation behaviour was successfully fabricated.

Methods

PLA (4032D, NaturedWorks Inc.) pellets were first dried at 80 °C for 24 hours prior to any treatment. Next, 10 wt% and 30 wt% PEG (2000 average molecular weight, Sigma Aldrich) was used as a plasticizer by melt-blending to PLA using a micro-compounder (DSM Xplore 15) at 170 °C and 100 RPM for 10 minutes. After compounding, the 3D-printable PLA/PEG filaments were fabricated by attaching an automatic roller at the end of the compounder. For material characterization, parts of the composite filaments were cut, transferred to a hot compression press (Carver Model 4386), and remolded at 170 °C under 5 metric tons of pressure. A customized 3D FDM printer (BigBox, BigBox 3D Ltd.) was utilized to fabricate the 4D components using a standard 0.3-mm nozzle with a nozzle temperature of 180 °C. Arc-shaped components were printed, which can be reshaped into a flat configuration once subjected to compression. The geometry of the component can be found in the Supplementary Information. The FG trilayer component was fabricated using a standard printing process segmented into three sections during which extruder motion was paused for filament exchange.

An analysis of the prefabricated composites and the 4D-printed components was conducted. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, IT-100, JEOL, Inc.) was used to study the plasticizing effect at the microscopic level and the cross-sectional morphology of the 4D FG layers. To verify the presence of PEG, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Alpha, Platinum-ATR, Bruker, Inc.) was conducted. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Q2000, TA Instrument) was used to study the glass transition and melting behaviour, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Q50, TA Instrument) was performed to characterize the degradation of the composites. During DSC testing, samples were heated from –50 °C to 230 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. For TGA, samples were heated from 30oC to 600 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. A dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA, Q800, TA Instrument) was used to characterize the mechanical, viscoelastic, and shape memory properties. Frequency sweep tests were conducted at room temperature with a 15-μm oscillation from 1 Hz to 50 Hz. For temperature ramp experiments, samples were first subjected to isothermal condition at 35 °C for 5 minutes, which was later increased to 100 °C at a heating rate of 3 °C/min under a constant 15-μm oscillation at 1 Hz. To study the high-temperature viscosity and plasticizing effects, rheological measurements (ARES, TA Instrument) were conducted. A parallel-plate rotational fixture was utilized while tests were conducted at 190 °C at an oscillation of 1 Hz to 100 Hz under a constant 1% oscillatory strain. Mechanical testing was conducted at both room temperature and a high temperature (70 °C). Due to the high stiffness behaviour of PLA, tensile tests at room temperature were conducted using a mechanical tensile tester (Instron 5848 MicroTester, Instron), while the DMA was used for high-temperature testing. Due to the machine constraint, room temperature tensile testing samples have a geometry of 10 mm in length, 7 mm in width, and 0.4 mm in thickness while DMA testing sample have a geometry of 5 mm in length, 4 mm in width, and 0.2 mm in thickness. For the tensile testing, a 5 mm/min extension was applied until failure. For DMA testing, samples were first conditioned at an isothermal testing temperature (70 °C) prior to applying a 50% strain/min rate until failure. To verify the SME, samples were conditioned at 70 °C and stretched to 200% strain with 50% strain/min rate. Both stress and strain were fixed as the temperature was lowered to room temperature. With stress removed, a heating rate of 3 °C/min was applied, and the amount of strain recovery was recorded.

To demonstrate 4D recovery, 3D-printed components were first deformed at 50 °C into a flat configuration. For the recovery process, a heat gun was placed directly above the flattened sample while the increase in temperature was simultaneously measured using an infrared radiation (IR) thermal camera (C3, FLIR).

References

Kruth, J.-P., Leu, M.-C. & Nakagawa, T. Progress in additive manufacturing and rapid prototyping. Cirp Annals 47, 525–540 (1998).

Guo, N. & Leu, M. C. Additive manufacturing: technology, applications and research needs. Frontiers of Mechanical Engineering 8, 215–243 (2013).

Ngo, T. D., Kashani, A., Imbalzano, G., Nguyen, K. T. & Hui, D. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): A review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Composites Part B: Engineering 143, 172–196 (2018).

Ahn, S.-H., Montero, M., Odell, D., Roundy, S. & Wright, P. K. Anisotropic material properties of fused deposition modeling ABS. Rapid prototyping journal 8, 248–257 (2002).

Bellini, A. & Güçeri, S. Mechanical characterization of parts fabricated using fused deposition modeling. Rapid Prototyping Journal 9, 252–264 (2003).

Gaytan, S. et al. Fabrication of barium titanate by binder jetting additive manufacturing technology. Ceramics International 41, 6610–6619 (2015).

Gonzalez, J., Mireles, J., Lin, Y. & Wicker, R. B. Characterization of ceramic components fabricated using binder jetting additive manufacturing technology. Ceramics International 42, 10559–10564 (2016).

Lee, M. P. et al. Development of a 3D printer using scanning projection stereolithography. Scientific reports 5, 9875 (2015).

Joe Lopes, A., MacDonald, E. & Wicker, R. B. Integrating stereolithography and direct print technologies for 3D structural electronics fabrication. Rapid Prototyping Journal 18, 129–143 (2012).

Cooke, M. N., Fisher, J. P., Dean, D., Rimnac, C. & Mikos, A. G. Use of stereolithography to manufacture critical-sized 3D biodegradable scaffolds for bone ingrowth. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials 64, 65–69 (2003).

Tibbits, S. 4D printing: multi-material shape change. Architectural Design 84, 116–121 (2014).

Chua, C. K. & Leong, K. F. 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing: Principles and Applications (with Companion Media Pack) of Rapid Prototyping Fourth Edition. (World Scientific Publishing Company, 2014).

Muth, J. T. et al. Embedded 3D printing of strain sensors within highly stretchable elastomers. Advanced Materials 26, 6307–6312 (2014).

Dodziuk, H. Applications of 3D printing in healthcare. Kardiochirurgia i torakochirurgia polska = Polish journal of cardio-thoracic surgery 13, 283 (2016).

Murphy, S. V. & Atala, A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nature biotechnology 32, 773 (2014).

Zarek, M. et al. 3D printing of shape memory polymers for flexible electronic devices. Advanced Materials 28, 4449–4454 (2016).

O’Donnell, J., Ahmadkhanlou, F., Yoon, H.-S. & Washington, G. In Active and Passive Smart Structures and Integrated Systems 2014. 905729 (International Society for Optics and Photonics).

Yap, Y. & Yeong, W. Shape recovery effect of 3D printed polymeric honeycomb: This paper studies the elastic behaviour of different honeycomb structures produced by PolyJet technology. Virtual and Physical Prototyping 10, 91–99 (2015).

Ning, F., Cong, W., Qiu, J., Wei, J. & Wang, S. Additive manufacturing of carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites using fused deposition modeling. Composites Part B: Engineering 80, 369–378 (2015).

Dudek, P. FDM 3D printing technology in manufacturing composite elements. Archives of Metallurgy and Materials 58, 1415–1418 (2013).

Zhang, Q. et al. 3D printing of graphene aerogels. Small 12, 1702–1708 (2016).

Leigh, S. J., Bradley, R. J., Purssell, C. P., Billson, D. R. & Hutchins, D. A. A simple, low-cost conductive composite material for 3D printing of electronic sensors. PloS one 7, e49365 (2012).

Khoo, Z. X. et al. 3D printing of smart materials: A review on recent progresses in 4D printing. Virtual and Physical Prototyping 10, 103–122 (2015).

Momeni, F., Liu, X. & Ni, J. A review of 4D printing. Materials & Design 122, 42–79 (2017).

Leist, S. K. & Zhou, J. Current status of 4D printing technology and the potential of light-reactive smart materials as 4D printable materials. Virtual and Physical Prototyping 11, 249–262 (2016).

Liu, C., Qin, H. & Mather, P. Review of progress in shape-memory polymers. Journal of Materials Chemistry 17, 1543–1558 (2007).

Behl, M. & Lendlein, A. Shape-memory polymers. Materials today 10, 20–28 (2007).

Huang, W., Yang, B., An, L., Li, C. & Chan, Y. Water-driven programmable polyurethane shape memory polymer: demonstration and mechanism. Applied Physics Letters 86, 114105 (2005).

Mendez, J. et al. Bioinspired mechanically adaptive polymer nanocomposites with water-activated shape-memory effect. Macromolecules 44, 6827–6835 (2011).

Jiang, H., Kelch, S. & Lendlein, A. Polymers move in response to light. Advanced Materials 18, 1471–1475 (2006).

Lendlein, A., Jiang, H., Jünger, O. & Langer, R. Light-induced shape-memory polymers. Nature 434, 879–882 (2005).

Ge, Q., Dunn, C. K., Qi, H. J. & Dunn, M. L. Active origami by 4D printing. Smart Materials and Structures 23, 094007 (2014).

Yu, K., Ritchie, A., Mao, Y., Dunn, M. L. & Qi, H. J. Controlled sequential shape changing components by 3D printing of shape memory polymer multimaterials. Procedia Iutam 12, 193–203 (2015).

Ambulo, C. P. et al. Four-dimensional Printing of Liquid Crystal Elastomers. ACS applied materials & interfaces 9, 37332–37339 (2017).

Wei, H. et al. Direct-Write Fabrication of 4D Active Shape-Changing Structures Based on a Shape Memory Polymer and Its Nanocomposite. ACS applied materials & interfaces 9, 876–883 (2016).

Gladman, A. S., Matsumoto, E. A., Nuzzo, R. G., Mahadevan, L. & Lewis, J. A. Biomimetic 4D printing. Nature materials 15, 413–418 (2016).

Raviv, D. et al. Active printed materials for complex self-evolving deformations. Scientific reports 4, 7422 (2014).

Ge, Q., Qi, H. J. & Dunn, M. L. Active materials by four-dimension printing. Applied Physics Letters 103, 131901 (2013).

Lewis, J. A. & Gratson, G. M. Direct writing in three dimensions. Materials today 7, 32–39 (2004).

Lewis, J. A. Direct ink writing of 3D functional materials. Advanced Functional Materials 16, 2193–2204 (2006).

Zhao, T. et al. 4D printing of shape memory polyurethane via stereolithography. European Polymer Journal 101, 120–126 (2018).

Pei, E. 4D Printing: dawn of an emerging technology cycle. Assembly Automation 34, 310–314 (2014).

Ly, S. T. & Kim, J. Y. 4D printing–fused deposition modeling printing with thermal-responsive shape memory polymers. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Green Technology 4, 267–272 (2017).

Hu, G., Damanpack, A., Bodaghi, M. & Liao, W. Increasing dimension of structures by 4D printing shape memory polymers via fused deposition modeling. Smart Materials and Structures 26, 125023 (2017).

Bodaghi, M. & Liao, W.-H. 4D Printed Tunable Mechanical Metamaterials with Shape Memory Operations. Smart Materials and Structures (2019).

Bodaghi, M., Damanpack, A. & Liao, W. Adaptive metamaterials by functionally graded 4D printing. Materials & Design 135, 26–36 (2017).

Miyamoto, Y., Kaysser, W., Rabin, B., Kawasaki, A. & Ford, R. G. Functionally graded materials: design, processing and applications. Vol. 5 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Kieback, B., Neubrand, A. & Riedel, H. Processing techniques for functionally graded materials. Materials Science and Engineering: A 362, 81–106 (2003).

Erdogan, F. Fracture mechanics of functionally graded materials. Composites Engineering 5, 753–770 (1995).

Tsotra, P. & Friedrich, K. Electrical and mechanical properties of functionally graded epoxy-resin/carbon fibre composites. Composites Part A: applied science and manufacturing 34, 75–82 (2003).

DiOrio, A. M., Luo, X., Lee, K. M. & Mather, P. T. A functionally graded shape memory polymer. Soft Matter 7, 68–74 (2011).

Lu, H., Huang, W. M. & Leng, J. Functionally graded and self-assembled carbon nanofiber and boron nitride in nanopaper for electrical actuation of shape memory nanocomposites. Composites Part B: Engineering 62, 1–4 (2014).

Bodaghi, M., Damanpack, A. & Liao, W. Triple shape memory polymers by 4D printing. Smart Materials and Structures 27, 065010 (2018).

Wang, X., Jiang, M., Zhou, Z., Gou, J. & Hui, D. 3D printing of polymer matrix composites: A review and prospective. Composites Part B: Engineering 110, 442–458 (2017).

Mohapatra, A. K., Mohanty, S. & Nayak, S. Effect of PEG on PLA/PEG blend and its nanocomposites: A study of thermo‐mechanical and morphological characterization. Polymer composites 35, 283–293 (2014).

Park, B. S., Song, J. C., Park, D. H. & Yoon, K. B. PLA/chain‐extended PEG blends with improved ductility. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 123, 2360–2367 (2012).

Baiardo, M. et al. Thermal and mechanical properties of plasticized poly (L-lactic acid). Journal of Applied Polymer Science 90, 1731–1738 (2003).

Chieng, B. W., Ibrahim, N. A., Yunus, W. M. Z. W. & Hussein, M. Z. Plasticized poly (lactic acid) with low molecular weight poly (ethylene glycol): Mechanical, thermal, and morphology properties. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 130, 4576–4580 (2013).

Serra, T., Planell, J. A. & Navarro, M. High-resolution PLA-based composite scaffolds via 3-D printing technology. Acta biomaterialia 9, 5521–5530 (2013).

Zhang, W., Chen, L. & Zhang, Y. Surprising shape-memory effect of polylactide resulted from toughening by polyamide elastomer. Polymer 50, 1311–1315 (2009).

Radjabian, M., Kish, M. & Mohammadi, N. Structure–property relationship for poly (lactic acid)(PLA) filaments: physical, thermomechanical and shape memory characterization. Journal of Polymer Research 19, 9870 (2012).

Yang, W. et al. Advanced shape memory technology to reshape product design, manufacturing and recycling. Polymers 6, 2287–2308 (2014).

Leist, S. K., Gao, D., Chiou, R. & Zhou, J. Investigating the shape memory properties of 4D printed polylactic acid (PLA) and the concept of 4D printing onto nylon fabrics for the creation of smart textiles. Virtual and Physical Prototyping 12, 290–300 (2017).

Cai, S., Sun, Y.-C., Ren, J. & Naguib, H. E. Toward the low actuation temperature of flexible shape memory polymer composites with room temperature deformability via induced plasticizing effect. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 5, 8845–8853 (2017).

Mi, H.-Y. et al. Characterization of thermoplastic polyurethane/polylactic acid (TPU/PLA) tissue engineering scaffolds fabricated by microcellular injection molding. Materials Science and Engineering: C 33, 4767–4776 (2013).

Hoidy, W. H., Ahmad, M. B., Al-Mulla, E. A. J. & Ibrahim, N. A. B. Preparation and characterization of polylactic acid/polycaprolactone clay nanocomposites. Journal of Applied sciences 10, 97–106 (2010).

Kolhe, P. & Kannan, R. M. Improvement in ductility of chitosan through blending and copolymerization with PEG: FTIR investigation of molecular interactions. Biomacromolecules 4, 173–180 (2003).

Bhattarai, N., Ramay, H. R., Gunn, J., Matsen, F. A. & Zhang, M. PEG-grafted chitosan as an injectable thermosensitive hydrogel for sustained protein release. Journal of Controlled Release 103, 609–624 (2005).

Huang, J. W., Chang Hung, Y., Wen, Y. L., Kang, C. C. & Yeh, M. Y. Polylactide/nano-and micro-scale silica composite films. II. Melting behavior and cold crystallization. Journal of applied polymer science 112, 3149–3156 (2009).

Hu, Y., Rogunova, M., Topolkaraev, V., Hiltner, A. & Baer, E. Aging of poly (lactide)/poly (ethylene glycol) blends. Part 1. Poly (lactide) with low stereoregularity. Polymer 44, 5701–5710 (2003).

Sheth, M., Kumar, R. A., Davé, V., Gross, R. A. & McCarthy, S. P. Biodegradable polymer blends of poly (lactic acid) and poly (ethylene glycol). Journal of applied polymer science 66, 1495–1505 (1997).

Sungsanit, K., Kao, N. & Bhattacharya, S. Properties of linear poly (lactic acid)/polyethylene glycol blends. Polymer Engineering & Science 52, 108–116 (2012).

Seo, M.-K., Lee, J.-R. & Park, S.-J. Crystallization kinetics and interfacial behaviors of polypropylene composites reinforced with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Materials Science and Engineering: A 404, 79–84 (2005).

Ozkoc, G. & Kemaloglu, S. Morphology, biodegradability, mechanical, and thermal properties of nanocomposite films based on PLA and plasticized PLA. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 114, 2481–2487 (2009).

Pillin, I., Montrelay, N. & Grohens, Y. Thermo-mechanical characterization of plasticized PLA: Is the miscibility the only significant factor? Polymer 47, 4676–4682 (2006).

Kokturk, G., Piskin, E., Serhatkulu, T. & Cakmak, M. Evolution of phase behavior and orientation in uniaxially deformed polylactic acid films. Polymer Engineering & Science 42, 1619–1628 (2002).

Lai, S.-M. & Lan, Y.-C. Shape memory properties of melt-blended polylactic acid (PLA)/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) bio-based blends. Journal of Polymer Research 20, 1–8 (2013).

Zhang, H., Wang, H., Zhong, W. & Du, Q. A novel type of shape memory polymer blend and the shape memory mechanism. Polymer 50, 1596–1601 (2009).

Meng, Q. & Hu, J. A review of shape memory polymer composites and blends. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 40, 1661–1672 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding support from different agencies for this research, including Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada, Government of Ontario, and Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the main manuscript text. Y.W., R.N. and M.C. fabricated and conducted characterization of the samples. H.N. supervised the work progress of the research project. All authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, YC., Wan, Y., Nam, R. et al. 4D-printed hybrids with localized shape memory behaviour: Implementation in a functionally graded structure. Sci Rep 9, 18754 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55298-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55298-1

This article is cited by

-

Butterfly metamorphosis inspired injectable in situ forming scaffolds with time-dependent pore formation for bone regeneration

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Enhancing shape-recovery ratio of 4D printed polylactic acid (PLA) structures through processing parameter optimization

Progress in Additive Manufacturing (2023)

-

A critical review on 4D printing and their processing parameters

International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM) (2023)

-

3D-Printed Objects for Multipurpose Applications

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2021)

-

Current progress of 4D-printing technology

Progress in Additive Manufacturing (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.