Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship between neuroendocrine hormones and clinical recovery following sport-related concussion (SRC). Ninety-five athletes (n = 56 male, n = 39 female) from a cohort of 11 interuniversity sport teams at a single institution provided blood samples; twenty six athletes with SRC were recruited 2–7 days post-injury, and 69 uninjured athletes recruited prior to the start of their competitive season. Concentrations of seven neuroendocrine hormones were quantitated in either plasma or serum by solid-phase chemiluminescent immunoassay. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool version 5 (SCAT-5) was used to evaluate symptoms at the time of blood sampling in all athletes. Multivariate partial least squares (PLS) analyses were used to evaluate the relationship between blood hormone concentrations and both (1) time to physician medical clearance and (2) initial symptom burden. A negative relationship was observed between time to medical clearance and both dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and progesterone; a positive relationship was found between time to medical clearance and prolactin. Cognitive, somatic, fatigue and emotion symptom clusters were associated with distinct neuroendocrine signatures. Perturbations to the neuroendocrine system in athletes following SRC may contribute to initial symptom burden and longer recovery times.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recovery from sport-related concussion (SRC) remains a challenging process for both patients and clinicians. While recovery most frequently occurs within 1–3 weeks of injury, a subset of individuals may take months before medical clearance return-to-play (RTP)1,2,3. The current standard of care following SRC includes an initial period of rest followed by graded stages of physical activity until full sport participation is reached2. This process relies heavily on self-reported symptoms that span impairments to cognition, balance, vision, physical and emotional health, as well as fatigue and sleep disturbances2,4,5. As symptom reporting and recovery time following SRC are inexorably tied to the underlying pathobiology of injury, it is only through a greater understanding of this relationship that improvements to treatment will arise.

Evidence from advanced neuroimaging has shown that cortical structures such as the parietal and temporal lobes can be affected after mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI)6,7. However, subcortical structures including those belonging to the limbic system and brainstem may also be vulnerable, as this region is considered the fulcrum of force vectors bearing the maximal rotational forces during injury8,9. This can lead to autonomic and/or neuroendocrine dysfunction, which has been observed across the entire severity spectrum of TBI10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Indeed, our group and others have utilized indices of heart rate variability to identify ANS dysfunction in the acute and subacute periods following SRC, potentially through disruption of parasympathetic activity12,13. With respect to neuroendocrine function, chronic pituitary dysfunction is the most frequently observed abnormality following mTBI; up to 37% of patients show evidence of hypopituitarism at one to five years post-injury, typically characterized by growth hormone deficiency14. In addition, pituitary abnormalities have also been observed chronically in sports associated with repetitive head impacts such as football and combat sports17,18,19.

While neuroendocrine abnormalities are often identified in the months to years following TBI, perturbations in the acute and subacute stages have also been reported. It has been suggested that women who suffer an mTBI in the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle, when progesterone is highest, may suffer from subsequent progesterone withdrawal leading to lower neurological outcomes and quality of life at one month post injury20. Furthermore, prior observations of elevated blood levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and triodothyronine within 48 h of an mTBI suggest that the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis may also be disrupted acutely after injury In view of this, Merchant-Borna and colleagues21 found perturbations in peripheral messenger RNA related to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in the subacute phase (7 days) after sport concussion. Similarly, a case series study of four football players sampled after injury showed that blood prolactin levels were acutely suppressed and subsequently increased throughout recovery22. And finally, in a study of 14 youth hockey players with SRC, abnormally low (<200 nmol/L) subacute blood cortisol levels were associated with increased symptom reporting and time to recovery in a subset of four athletes23.

While evidence of perturbations to both the neuroendocrine and ANS systems have been observed in the acute and subacute period following SRC, it is unclear how this correlates with clinical indices such as symptoms and recovery time. This is particularly relevant to the study of neuroendocrine hormones, given their relationship to a litany of physical and psychological disorders and their profound influence on somatic and behavioural symptomology24. Greater knowledge of these relationships in SRC may not only advance our understanding of concussion pathophysiology but may also aid in the development and implementation of therapies that augment the neuroendocrine and ANS systems, such as exercise, mindfulness training, and biofeedback25.

Hence, the purpose of this study was to evaluate a panel of neuroendocrine hormones in relation to symptom reporting and recovery in a group of interuniversity athletes within the first week following SRC. We hypothesized that greater symptom burden and longer recovery times would correlate with blood concentrations of neuroendocrine hormones.

Results

Participant characteristics

Athlete characteristics are described in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age and time from last concussion between healthy athletes and athletes with SRC. Athletes with SRC reported a significantly greater number of symptoms (p < 0.001) and symptom severity (p < 0.001) compared to healthy athletes. The greatest mean differences in symptom clusters between athletes with SRC and healthy athletes were observed for cognitive (median = 6 (SRC) vs. 0 (healthy), bootstrap ratio (BSR) 9.7, p < 0.001) and somatic (median = 12 (SRC) vs. 0 (healthy), BSR = 8.2, p < 0.001) symptoms. No athletes with SRC reported loss of consciousness. For a complete description of athlete enrolment and selection, please see both Fig. 1 and the participants section of the methods.

Athlete enrollment from objective measures of sport concussion project, and study participant selection. *One subject removed due to missing symptoms, and one subject removed due to missing values in five of seven hormones. **Thirteen subjects were removed due to subsequent concussion and recruitment in the SRC group; 28 subjects were excluded because they had their blood drawn prior to 11am; 45 subjects were removed because they had exercised within 24 h; 10 subjects were excluded due to repeated enrollment in subsequent years (only a single enrolment per subject was allowed).

Hormone profiles between athletes with SRC and healthy athletes

Hormone concentrations in athletes with SRC and healthy athletes can be seen in Table 2. PLSDA analysis of hormone profiles yielded no significant differences between groups.

Correlation between hormone profiles and days to medical clearance in athletes with SRC

PLS analysis of the relationship between days to medical clearance and blood hormone concentrations in athletes following SRC can be seen in Fig. 2. A significant positive relationship between days to medical clearance and prolactin concentrations was observed (BSR = 3.3, p < 0.001). In addition, a significant negative relationship was found between days to medical clearance and both progesterone (BSR = 2.4, p = 0.02) and DHEA-S (BSR = 3.3, p = 0.001).

Correlation between neuroendocrine hormones and days to medical clearance. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (FT4), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), and adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH). Plot shows the correlations between neuroendocrine hormones measured in the subacute period following sport-related concussion (SRC) and days to medical clearance by partial least squares (PLS) analysis. Bars represent biomarker loadings and standard errors derived from bootstrapped resampling (5000 samples). Green bars = significant at a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05.

Correlation between hormone profiles and symptoms in athletes with SRC

A plot of the PLS analyses evaluating the relationship between symptoms clusters and blood hormone levels can be found in Fig. 3. The somatic symptom cluster in athletes with SRC was negatively correlated with blood concentrations of all hormones excluding prolactin and TSH, with the greatest effects seen for DHEA-S (BSR = 5.5, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3A).

Correlation between neuroendocrine hormones and symptom clusters. Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH), (DHEA-S), free thyroxine (FT4), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). Plots show the correlations between neuroendocrine hormones measured in the subacute period following sport-related concussion and (A) somatic symptoms, (B) cognitive symptoms, (C) fatigue symptoms, and (D) emotion symptoms, by partial least squares (PLS) analysis. Bars represent biomarker loadings and standard errors derived from bootstrapped resampling (5000 samples). Green bars = significant correlation with days to recovery at a false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05.

The cognitive symptom cluster was significantly associated with all blood hormone concentrations excluding FT4 and TSH; symptoms were negatively correlated with ACTH, cortisol, DHEA-S and progesterone, with DHEA-S showing the greatest effects (BSR = 6.1, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). In addition, the cognitive cluster was the only symptom cluster positively associated with prolactin concentrations (BSR = 2.1, p = 0.03) (Fig. 3B).

The fatigue symptom cluster was negatively correlated with cortisol (BSR = 3.4, p < 0.001), DHEA-S (BSR = 4.4, p < 0.001) and progesterone (BSR = 4.6, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3C). Finally, we observed a significant negative relationship between symptoms of emotion and both DHEA-S (BSR = 2.9, p = 0.003) and progesterone (BSR = 4.7, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3D).

Discussion

The main finding of the current study was that greater symptom burden and longer time to medical clearance were correlated with neuroendocrine hormones measured in the blood of athletes following SRC. Importantly, we did not find group-level differences in neuroendocrine hormones between athletes with SRC and healthy athletes, suggesting that perturbations to the neuroendocrine system may not be a ubiquitous biological consequence of concussion but exist only in those with unfavorable clinical profiles.

We observed a negative relationship between days to medical clearance and blood concentrations of both DHEA-S and progesterone in athletes with SRC. Moreover, both hormones were negatively corelated with all self-reported symptom clusters (somatic, cognitive, fatigue, emotion). That lower levels of DHEA-S and progesterone were related to increased symptom burden and longer recovery times is consistent with a large body of animal and human evidence which has identified a potential therapeutic benefit of DHEA-S and progesterone following moderate and severe TBI26,27,28,29,30,31,32. DHEA-S is as a pro-excitatory neurosteroid that may alleviate glutamate excitotoxicity33,34, promote dendrite arborization35, and increase cholinergic neurotransmission36. In rodent models of mild-to-moderate TBI, DHEA-S treatment has been shown to improve behavioural recovery in sensorimotor and cognitive tasks following injury29,30,31.

While progesterone is derived from a common precursor to DHEA-S, pregnenolone, the neurophysiologic effects of progesterone differ from that of DHEA-S. Yet, progesterone has also been considered as a potential therapeutic target for TBI26,27,28,32 as it may reduce cerebral edema and blood brain barrier disruption, as well as limit oxidative stress and inflammation post-injury37,38,39,40. In humans, stage II clinical trials have shown potential for progesterone as a neuroprotective agent following moderate and severe TBI41,42. Although therapeutic benefits were not observed in Stage III trials43,44, this isn’t surprising given the heterogeneity and complexity of TBI, and thus it is still likely that progesterone is involved in injury pathophysiology. Taken together, our results are consistent with the body of literature that suggests both DHEA-S and progesterone influence recovery and symptomology following concussion.

In addition to DHEA-S, we observed a negative relationship between ACTH, cortisol and somatic, cognitive and fatigue (cortisol only) symptom clusters. These results are supported by the findings of Merchant-Borna and colleagues21 who observed a downregulation of a number of HPA-axis genes in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of athletes measured seven days following SRC, and are also in-line with those of Ritchie and colleagues23, who found that lower cortisol levels in pediatric sport concussion were related with longer recovery and greater symptom burden. While our group-level analysis did not identify differences in hormone concentrations between athletes with SRC and healthy athletes, our correlational analyses highlight that these hormones may only be lower in a subset of injured athletes experiencing greater symptom burden. We also observed that greater somatic symptoms correlated with lower concentrations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis hormone FT4. In view of this, Cernak and colleagues45 identified elevated blood concentrations of TSH acutely following mTBI. While we did not find any significant group differences or correlations with TSH concentrations, and did not clinically evaluate athletes for the presence of thyroid dysfunction, our data, along with that of Cernak and colleagues, is consistent with the direction of TSH and FT4 levels found in the blood of patients with overt hypothyroidism46, and suggests that dysfunction of the HPT axis may be present in a subset of concussed individuals presenting with higher somatic symptoms.

We observed that higher symptoms of emotion were associated with lower progesterone and DHEA-S concentrations. Interestingly, both progesterone and DHEA-S have been correlated with improvements to mood and behavior47,48,49,50. While the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood, these results justify future research into the role of these hormones in both injury-related affect and the potential development of mental health issues following concussion; it has been theorized that disruption to the neuroendocrine system may play an important mediating role51.

We observed a positive correlation between blood concentrations of prolactin and both days to medical clearance and cognitive symptom reporting. These findings are consistent with severe TBI studies where prolactin levels are often elevated following injury and may infer damage to the hypothalamus52,53,54. However, our findings differ from the only other known related study in sport concussion; in a case series of four male football players, it was observed that concussion recovery was associated with suppressed prolactin levels that increased throughout recovery22. Yet, prolactin is the most biologically diverse pituitary hormone, with numerous functions including the modulation of metabolism, immunity, behavior, lactation, and reproduction55. Our understanding of the role of prolactin in the sequelae of sport concussion remains limited, however, our findings warrant further investigation.

The summation of the results in the present study are consistent with other facets of secondary injury previously observed following SRC by our group, namely oxidative stress56, and inflammation57,58. Specifically, we have previously identified higher concentrations of the oxidative stress marker PRDX-6 in athletes following SRC56, and also found that days to medical clearance was positively correlated with blood concentrations of the inflammatory chemokines monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 and MCP-459. In the current study, greater symptom burden and recovery time were associated with lower DHEA-S and progesterone; progesterone may limit oxidative stress following TBI, while DHEA-S and progesterone have both been associated with reducing neuroinflammation30,37. In addition, we observed that higher levels of prolactin - a potential proinflammatory mediator - were related to increased time to recovery and cognitive symptom reporting60,61. Hence, the relationship between an unfavorable clinical profile (symptom reporting and time to medical clearance), lower levels of hormones theorized to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress (DHEA-S and progesterone), and higher levels of a proinflammatory-associated hormone (prolactin) are consistent with our previous works and support a role for the neuroendocrine system in multiple facets of secondary injury.

There were several limitations in the current study that must be considered when interpreting the results. First, while we controlled for the effects of sex, a larger sample size would have allowed for separate male and female analyses, including controlling for menstrual cycle phase and birth control use in female athletes. Furthermore, the absence of morning fasting blood samples precluded clinical quantitation of patients as “normal” or “abnormal” for individual hormone concentrations. In order to maximize participant recruitment while avoiding diurnal variation, we chose a sampling period between 11:00am and 6:00 pm. Specifically, this allowed us to avoid the typical morning peaks seen with hormones such as prolactin, cortisol and progesterone62,63,64. In addition, we measured DHEA-S, which displays less diurnal variation than DHEA64,65, implemented a partial regression to eliminate the statistical variance caused by changes in hormone concentrations related to the time of day of blood sampling, and evaluated the potential relationship between hormones and the time from injury to blood sampling (no significant correlations found by PLS; data not shown). Yet, a narrower sample timing may still have been helpful in reducing biological noise. Lastly, while uninjured athletes in the current study were recruited from a potential pool of 11 sports selected a priori due to their high risk for concussion, our institution enrolls concussions from athletes participating in any sport. Hence, this creates a potential risk for selection bias. However, we do not feel that this significantly impacted our results as they pertain to concussion; while sports varied within and between groups, our cohort had adequate representation from sport types characterized by no contact, incidental contact, and purposeful contact/collision. In addition, while it is theoretically possible that the athletes within the SRC group may differ from those who did not agree to participate, both the medical time to clearance and symptom burden found in the current study are in-line with previous studies by our group using different samples from an athlete population3,59,66.

Neuroendocrine hormones measured in the peripheral blood following SRC correlate with higher symptom reporting and longer time to medical clearance. Specifically, an unfavorable clinical profile correlates with a blood hormone signature that is characterized by lower HPA-axis activity, lower progesterone, and elevated prolactin. Future research is warranted to elucidate the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary axes in concussion pathophysiology, and its potential involvement with other secondary injury processes such as inflammation and oxidative stress.

Methods

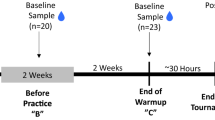

Participants

Participant eligibility and enrolment information can be seen in Fig. 1. From August 2016 – November 2017, 692 uninjured athletes and 59 athletes with an SRC were eligible for participation in the current study as part of a larger multi-year study being conducted at a single academic institution. Of this cohort, 583 uninjured athletes were enrolled prior to the start of their competitive season, and 32 athletes with SRC were enrolled at the time of their injury: blood was taken from 165 uninjured athletes during preseason baseline testing and from 28 athletes within seven days of an SRC. Due to an absence of symptom or hormone data, two athletes were excluded from the SRC group. In addition, 96 athletes were excluded from the uninjured cohort; 13 healthy athletes suffered a concussion and were therefore moved to the SRC group, 28 were removed due to blood draws prior to 11am, 45 were removed due to exercising within 24 h of blood sampling, and 10 athletes were removed due to having multiple samples. Hence, a final sample of 95 athletes (male = 56, female = 39) from 11 interuniveristy sports were enrolled, comprising 69 uninjured athletes and 26 athletes with an SRC (Table 1). Concussion diagnosis was performed by a sport medicine physician at an academic sport medicine clinic, in accordance with the Concussion in Sport Group statement2. Medical clearance for unrestricted activity (i.e., clinical recovery) was determined by a physician with expertise in sport and exercise medicine from a single institution. Specifically, clinical recovery required (1) athletes to be asymptomatic at rest, and (2) completion of a graded return-to-play (RTP) protocol. RTP stages included: light aerobic exercise, more intensive training, sports-specific exercises, non-contact participation (i.e., low risk practice), and high-risk practice. Finally, following the completion of RTP stages, the physician ensured a return to their baseline level of cognitive functioning and neurological functioning. Exclusion criteria for all study participants included a history of SRC within six months of study participation, a history of neuroendocrine disorders, exercise within 24 h of enrollment, or blood sampling prior to 11am. All study participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment, and all study procedures were in accordance of the declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board, University of Toronto (protocol reference # 27958).

Blood sampling

Blood was sampled from athletes with an SRC within seven days of injury (median = 3.5, range = 2–7), while uninjured athletes were sampled at an assessment prior to their competitive season. All samples were taken between 11:00am and 6:00 pm. Blood was not taken from athletes who presented with a known acute infection or illness at the time of sampling or were taking any medications beyond birth control. Venous blood was drawn into 10-mL K2EDTA and 4-mL serum vacutainers (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA), where it equilibrated for approx. one hour at room temperature, followed by a two min centrifugation using a PlasmaPrep 12TM centrifuge (Separation Technology Inc., FL, USA). The supernatant was then aliquoted and frozen at −70 °C until analysis.

Hormone analysis

Blood concentrations of seven hormones were quantitated by solid-phase chemiluminescent immunoassay via the Immulite 1000 analyzer (Siemens Healthineers Global, Erlangen, Germany). Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was run on plasma supernatant, while serum supernatant was used for the remaining six hormones: cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), free thyroxine (FT4), progesterone, prolactin, and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH).

Symptom reporting

The Post-Concussion Symptom Scale (PCSS) was administered to all athletes at the time of blood draw. The PCSS is a 22-item symptom inventory checklist using a seven-point likert scale rating included in the most recent Sport Concussion Assessment Tool version 5 (SCAT-5)67. Symptoms were clustered into four categories for statistical analysis: somatic (headache, pressure in head, neck pain, nausea/vomiting, dizziness, blurred vision, balance problems, sensitivity to light, sensitivity to noise), cognitive (feeling slowed down, feeling “in a fog”, “don’t feel right”, difficulty concentrating, difficulty remembering, confusion), fatigue and sleep problems (fatigue/low energy, drowsiness, trouble falling asleep) and emotion (more emotional, irritability, sadness, nervous/anxious)68.

Statistical analysis

Hormones were statistically quantitated if they fell within the assay detection range as stated by the manufacturer: ACTH (9–1250 pg/mL), Cortisol (28–1380 nmol/L), DHEA-S (0.41–27μmol/L), progesterone (0.64–127 nmol/L), prolactin (11–3180 mIU/L), TSH (0.004–75 μIU/L), and FT4 (3.9–77.2 pmol/L). One participant for each of ACTH and TSH had a single value below the assay detection limit; these values were imputed with ½ the lower limit of detection. Two prolactin values were >5 standard deviations (SDs) above the mean, and one TSH value was >7 SDs above the mean; these values were deemed outliers and were removed and imputed with the respective median hormone values from the appropriate group.

Prior to statistical analysis and following outlier removal and imputation, hormone values were checked for violations of normality. Skewness and kurtosis for SRC and healthy hormone values were separately evaluated against 1000 resamples of a random normal gaussian model. In athletes with SRC, skewness ranged from −1.8 (p < 0.001) to 2.4 (p < 0.001), and kurtosis ranged from 2.9 (p = 0.799) to 8.5 (p = 0.001). In uninjured athletes, skewness ranged from −1.1 (p < 0.002) to 5.3 (p < 0.001), and kurtosis ranged from 3.7 (p = 0.161) to 34.8 (p < 0.001). Hence, all data was rank transformed prior to statistical evaluation.

Between-group comparisons (SRC vs. healthy) of athlete characteristics (age, total symptoms, symptom severity, somatic, cognitive, fatigue and emotion symptoms) were calculated by bootstrap resampling (5000 iterations) in order to generate a bootstrap ratio (BSR) (effect size; mean/standard deviation (SD)) of the mean difference. From this, an empirical p value was obtained and corrected at a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 0.05.

Prior to multivariate analysis, A partial regression was implemented to remove the confounding influence of time-of-day of sampling on blood hormone concentrations. For each hormone, separate ordinary least squares regression tests were run on rank-transformed data against time of day of blood sampling. The residual values of each test were then used as the adjusted hormone values for further analysis.

Hormone profiles between athletes with SRC and healthy athletes were analyzed by partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLSDA)69. PLSDA is a multivariate tool used to maximize the covariance between a set of predictor variables (hormones) and a binary response variable (SRC vs. healthy). The PLSDA was run in a bootstrap resampled framework (5000 iterations), followed by the generation of BSRs and empirical p values, corrected at an FDR of 0.05. Due to the difference in hormone profiles between males and females (data not shown), prior to PLSDA, rank-normalized hormone values were transformed into z-scores created separately on male and female participants.

A correlational PLS (PLSC) was used to evaluate the relationship between hormones and (1) symptom clusters and (2) days to physician medical clearance. PLSC is similar to PLSDA, but allows the evaluation of continuous response variables69. Prior to PLSC analysis, hormone z-scores were generated separately for male and female athletes with SRC using the mean of the hormone values in their respective healthy athlete groups. For PLS plots, hormones are represented by the mean and standard error of the bootstrapped loadings (Figs. 1 and 2).

Data availability

All data is available upon request due to privacy restrictions.

References

Williams, R. M., Puetz, T. W., Giza, C. C. & Broglio, S. P. Concussion recovery time among high school and collegiate athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 45, 893–903, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0325-8 (2015).

McCrory, P. et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport-the 5(th) international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med 51, 838–847, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097699 (2017).

Lawrence, D. W., Richards, D., Comper, P. & Hutchison, M. G. Earlier time to aerobic exercise is associated with faster recovery following acute sport concussion. PLoS One 13, e0196062, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196062 (2018).

Moser, R. S. et al. Neuropsychological evaluation in the diagnosis and management of sports-related concussion. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 22, 909–916, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2007.09.004 (2007).

Langlois, J. A., Rutland-Brown, W. & Wald, M. M. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil 21, 375–378 (2006).

Churchill, N. W. et al. Neuroimaging of sport concussion: persistent alterations in brain structure and function at medical clearance. Sci Rep 7, 8297, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07742-3 (2017).

McDonald, B. C., Saykin, A. J. & McAllister, T. W. Functional MRI of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI): progress and perspectives from the first decade of studies. Brain Imaging Behav 6, 193–207, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-012-9173-4 (2012).

Barrio, J. R. et al. In vivo characterization of chronic traumatic encephalopathy using [F-18]FDDNP PET brain imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, E2039–2047, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1409952112 (2015).

Ropper, A. H. & Gorson, K. C. Clinical practice. Concussion. N Engl J Med 356, 166–172, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp064645 (2007).

Di Battista, A. P. et al. Inflammatory cytokine and chemokine profiles are associated with patient outcome and the hyperadrenergic state following acute brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 13, 40, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-016-0500-3 (2016).

Esterov, D. & Greenwald, B. D. Autonomic Dysfunction after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Sci 7, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7080100 (2017).

Hutchison, M. G. et al. Psychological and Physiological Markers of Stress in Concussed Athletes Across Recovery Milestones. J Head Trauma Rehabil 32, E38–E48, https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000252 (2017).

Pertab, J. L. et al. Concussion and the autonomic nervous system: An introduction to the field and the results of a systematic review. NeuroRehabilitation 42, 397–427, https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-172298 (2018).

Bondanelli, M. et al. Occurrence of pituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 21, 685–696, https://doi.org/10.1089/0897715041269713 (2004).

Tanriverdi, F., Unluhizarci, K., Karaca, Z., Casanueva, F. F. & Kelestimur, F. Hypopituitarism due to sports related head trauma and the effects of growth hormone replacement in retired amateur boxers. Pituitary 13, 111–114, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-009-0204-0 (2010).

Tanriverdi, F., Unluhizarci, K. & Kelestimur, F. Pituitary function in subjects with mild traumatic brain injury: a review of literature and proposal of a screening strategy. Pituitary 13, 146–153, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-009-0215-x (2010).

Kelestimur, F. Chronic trauma in sports as a cause of hypopituitarism. Pituitary 8, 259–262, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-006-6051-3 (2005).

Kelestimur, F. et al. Boxing as a sport activity associated with isolated GH deficiency. J Endocrinol Invest 27, RC28–32, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03345299 (2004).

Kelly, D. F. et al. Prevalence of pituitary hormone dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, and impaired quality of life in retired professional football players: a prospective study. J Neurotrauma 31, 1161–1171, https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2013.3212 (2014).

Wunderle, K., Hoeger, K. M., Wasserman, E. & Bazarian, J. J. Menstrual phase as predictor of outcome after mild traumatic brain injury in women. J Head Trauma Rehabil 29, E1–8, https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000006 (2014).

Merchant-Borna, K. et al. Genome-Wide Changes in Peripheral Gene Expression following Sports-Related Concussion. J Neurotrauma 33, 1576–1585, https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.4191 (2016).

La Fountaine, M. F., Toda, M., Testa, A. & Bauman, W. A. Suppression of Serum Prolactin Levels after Sports Concussion with Prompt Resolution Upon Independent Clinical Assessment To Permit Return-to-Play. J Neurotrauma 33, 904–906, https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.3968 (2016).

Ritchie, E. V., Emery, C. & Debert, C. T. Analysis of serum cortisol to predict recovery in paediatric sport-related concussion. Brain Inj 32, 523–528, https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2018.1429662 (2018).

Chrousos, G. P. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat Rev Endocrinol 5, 374–381, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2009.106 (2009).

van der Zwan, J. E., de Vente, W., Huizink, A. C., Bogels, S. M. & de Bruin, E. I. Physical activity, mindfulness meditation, or heart rate variability biofeedback for stress reduction: a randomized controlled trial. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 40, 257–268, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9293-x (2015).

Pettus, E. H., Wright, D. W., Stein, D. G. & Hoffman, S. W. Progesterone treatment inhibits the inflammatory agents that accompany traumatic brain injury. Brain Res 1049, 112–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.004 (2005).

Cutler, S. M., VanLandingham, J. W., Murphy, A. Z. & Stein, D. G. Slow-release and injected progesterone treatments enhance acute recovery after traumatic brain injury. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 84, 420–428, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2006.05.029 (2006).

Cutler, S. M. et al. Progesterone improves acute recovery after traumatic brain injury in the aged rat. J Neurotrauma 24, 1475–1486, https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2007.0294 (2007).

Hoffman, S. W., Virmani, S., Simkins, R. M. & Stein, D. G. The delayed administration of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate improves recovery of function after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 20, 859–870, https://doi.org/10.1089/089771503322385791 (2003).

Malik, A. S. et al. A novel dehydroepiandrosterone analog improves functional recovery in a rat traumatic brain injury model. J Neurotrauma 20, 463–476, https://doi.org/10.1089/089771503765355531 (2003).

Milman, A., Zohar, O., Maayan, R., Weizman, R. & Pick, C. G. DHEAS repeated treatment improves cognitive and behavioral deficits after mild traumatic brain injury. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 18, 181–187, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.05.007 (2008).

Lopez-Rodriguez, A. B. et al. Correlation of brain levels of progesterone and dehydroepiandrosterone with neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury in female mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 56, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.02.018 (2015).

Kimonides, V. G., Khatibi, N. H., Svendsen, C. N., Sofroniew, M. V. & Herbert, J. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (DHEAS) protect hippocampal neurons against excitatory amino acid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 1852–1857 (1998).

Cardounel, A., Regelson, W. & Kalimi, M. Dehydroepiandrosterone protects hippocampal neurons against neurotoxin-induced cell death: mechanism of action. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 222, 145–149 (1999).

Compagnone, N. A. & Mellon, S. H. Dehydroepiandrosterone: a potential signalling molecule for neocortical organization during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 4678–4683 (1998).

Rhodes, M. E., Li, P. K., Flood, J. F. & Johnson, D. A. Enhancement of hippocampal acetylcholine release by the neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate: an in vivo microdialysis study. Brain Res 733, 284–286 (1996).

Webster, K. M. et al. Progesterone treatment reduces neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and brain damage and improves long-term outcomes in a rat model of repeated mild traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 12, 238, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0457-7 (2015).

Roof, R. L., Duvdevani, R., Braswell, L. & Stein, D. G. Progesterone facilitates cognitive recovery and reduces secondary neuronal loss caused by cortical contusion injury in male rats. Exp Neurol 129, 64–69, https://doi.org/10.1006/exnr.1994.1147 (1994).

Roof, R. L., Duvdevani, R., Heyburn, J. W. & Stein, D. G. Progesterone rapidly decreases brain edema: treatment delayed up to 24 hours is still effective. Exp Neurol 138, 246–251, https://doi.org/10.1006/exnr.1996.0063 (1996).

Djebaili, M., Guo, Q., Pettus, E. H., Hoffman, S. W. & Stein, D. G. The neurosteroids progesterone and allopregnanolone reduce cell death, gliosis, and functional deficits after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 22, 106–118, https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2005.22.106 (2005).

Wright, D. W. et al. ProTECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med 49(391-402), 402 e391–392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.932 (2007).

Xiao, G., Wei, J., Yan, W., Wang, W. & Lu, Z. Improved outcomes from the administration of progesterone for patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care 12, R61, https://doi.org/10.1186/cc6887 (2008).

Skolnick, B. E. et al. A clinical trial of progesterone for severe traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 371, 2467–2476, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1411090 (2014).

Wright, D. W. et al. Very early administration of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 371, 2457–2466, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1404304 (2014).

Cernak, I., Savic, V. J., Lazarov, A., Joksimovic, M. & Markovic, S. Neuroendocrine responses following graded traumatic brain injury in male adults. Brain Inj 13, 1005–1015 (1999).

Khandelwal, D. & Tandon, N. Overt and subclinical hypothyroidism: who to treat and how. Drugs 72, 17–33, https://doi.org/10.2165/11598070-000000000-00000 (2012).

Vincent, K. et al. “Luteal Analgesia”: Progesterone Dissociates Pain Intensity and Unpleasantness by Influencing Emotion Regulation Networks. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9, 413, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00413 (2018).

Bosch, O. G. et al. Gamma-hydroxybutyrate enhances mood and prosocial behavior without affecting plasma oxytocin and testosterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology 62, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.167 (2015).

Ben Dor, R., Marx, C. E., Shampine, L. J., Rubinow, D. R. & Schmidt, P. J. DHEA metabolism to the neurosteroid androsterone: a possible mechanism of DHEA’s antidepressant action. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232, 3375–3383, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-015-3991-1 (2015).

Sripada, R. K. et al. DHEA enhances emotion regulation neurocircuits and modulates memory for emotional stimuli. Neuropsychopharmacology 38, 1798–1807, https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.79 (2013).

Molaie, A. M. & Maguire, J. Neuroendocrine Abnormalities Following Traumatic Brain Injury: An Important Contributor to Neuropsychiatric Sequelae. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9, 176, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00176 (2018).

Tandon, A. et al. Assessment of endocrine abnormalities in severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 151, 1411–1417, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-009-0444-9 (2009).

Prasanna, K. L., Mittal, R. S. & Gandhi, A. Neuroendocrine dysfunction in acute phase of moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Brain Inj 29, 336–342, https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2014.955882 (2015).

Woolf, P. D. Hormonal responses to trauma. Crit Care Med 20, 216–226 (1992).

Fitzgerald, P. & Dinan, T. G. Prolactin and dopamine: what is the connection? A review article. J Psychopharmacol 22, 12–19, https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216307087148 (2008).

Di Battista, A. P. et al. An investigation of neuroinjury biomarkers after sport-related concussion: from the subacute phase to clinical recovery. Brain Inj, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2018.1432892 (2018).

Di Battista, A. P. et al. Blood biomarkers are associated with brain function and blood flow following sport concussion. J Neuroimmunol 319, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.03.002 (2018).

Di Battista, A. P., Churchill, N., Rhind, S. G., Richards, D. & Hutchison, M. G. Evidence of a distinct peripheral inflammatory profile in sport-related concussion. J Neuroinflammation Under Review (2018).

Di Battista, A. P., Churchill, N., Rhind, S. G., Richards, D. & Hutchison, M. G. Evidence of a distinct peripheral inflammatory profile in sport-related concussion. J Neuroinflammation 16, 17, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-019-1402-y (2019).

Brand, J. M. et al. Prolactin triggers pro-inflammatory immune responses in peripheral immune cells. Eur Cytokine Netw 15, 99–104 (2004).

Pereira Suarez, A. L., Lopez-Rincon, G., Martinez Neri, P. A. & Estrada-Chavez, C. Prolactin in inflammatory response. Adv Exp Med Biol 846, 243–264, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12114-7_11 (2015).

Waldstreicher, J. et al. Gender differences in the temporal organization of proclactin (PRL) secretion: evidence for a sleep-independent circadian rhythm of circulating PRL levels- a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81, 1483–1487, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.81.4.8636355 (1996).

Birketvedt, G. S. et al. Diurnal secretion of ghrelin, growth hormone, insulin binding proteins, and prolactin in normal weight and overweight subjects with and without the night eating syndrome. Appetite 59, 688–692, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.07.015 (2012).

van Kerkhof, L. W. et al. Diurnal Variation of Hormonal and Lipid Biomarkers in a Molecular Epidemiology-Like Setting. PLoS One 10, e0135652, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135652 (2015).

Kroboth, P. D., Salek, F. S., Pittenger, A. L., Fabian, T. J. & Frye, R. F. DHEA and DHEA-S: a review. J Clin Pharmacol 39, 327–348 (1999).

Churchill, N. W., Hutchison, M. G., Graham, S. J. & Schweizer, T. A. Evaluating Cerebrovascular Reactivity during the Early Symptomatic Phase of Sport Concussion. J Neurotrauma 36, 1518–1525, https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2018.6024 (2019).

Echemendia, R. J. et al. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (SCAT5): Background and rationale. Br J Sports Med 51, 848–850, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097506 (2017).

Churchill, N. W., Hutchison, M. G., Graham, S. J. & Schweizer, T. A. Symptom correlates of cerebral blood flow following acute concussion. Neuroimage Clin 16, 234–239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2017.07.019 (2017).

Krishnan, A., Williams, L. J., McIntosh, A. R. & Abdi, H. Partial Least Squares (PLS) methods for neuroimaging: a tutorial and review. Neuroimage 56, 455–475, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.034 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ingrid Smith, Sarah Watling and Maria Shiu for their technical assistance. This research was funded by Defence Research & Development Canada (DRDC) and the Canadian Institutes of Military and Veterans Health (CIMVHR). This study was approved by the Canadian Forces Surgeon General’s Health Research Program. In accordance with the Department of National Defence policy, the paper was reviewed and approved for submission without modification by the DRDC Publications Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: All authors. Data acquisition: A.P.D., M.G.H., S.G.R. Data analysis: A.P.D., M.G.H., N.C., S.G.R., D.W.L. Data interpretation: A.P.D., M.G.H., N.C., S.G.R., D.R. Drafting of manuscript: A.P.D. Revising manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Battista, A.P., Rhind, S.G., Churchill, N. et al. Peripheral blood neuroendocrine hormones are associated with clinical indices of sport-related concussion. Sci Rep 9, 18605 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54923-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54923-3

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.