Abstract

Fluctuations in the clonal composition of Group A Streptococcus (GAS) have been associated with the emergence of successful lineages and with upsurges of invasive infections (iGAS). This study aimed at identifying changes in the clones causing iGAS in Portugal. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, emm typing and superantigen (SAg) gene profiling were performed for 381 iGAS isolates from 2010–2015. Macrolide resistance decreased to 4%, accompanied by the disappearance of the M phenotype and an increase of the iMLSB phenotype. The dominant emm types were: emm1 (28%), emm89 (11%), emm3 (9%), emm12 (8%), and emm6 (7%). There were no significant changes in the prevalence of individual emm types, emm clusters, or SAg profiles when comparing to 2006–2009, although an overall increasing trend was recorded during 2000–2015 for emm1, emm75, and emm87. Short-term increases in the prevalence of emm3, emm6, and emm75 may have been driven by concomitant SAg profile changes observed within these emm types, or reflect the emergence of novel genomic variants of the same emm types carrying different SAgs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Streptococcus pyogenes (Lancefield Group A Streptococcus, GAS) can cause a wide spectrum of disease, ranging from superficial infections of the throat and skin, such as pharyngitis and impetigo, to severe invasive infections including necrotizing fasciitis, bacteraemia, and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. In addition, immune-mediated non-suppurative sequelae, such as acute rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis, remain prevalent in low-income countries and some indigenous populations1,2. Despite the global disease burden associated with this pathogen, implicating over 517,000 deaths each year1, a safe and effective vaccine has never reached the market3. The most promising candidate is a multivalent vaccine based on the hypervariable N-terminal region of the M protein, a major virulence factor and immunogenic protein of GAS. The variability of this N-terminal region is also the basis for the M-serotyping scheme that was used for decades to discriminate GAS strains and that was later replaced by the sequencing of the corresponding hypervariable gene region, known as emm typing4. More recently, a classification scheme based on the entire sequence of the emm gene that clusters closely related M proteins with similar functional and host factor binding properties, was proposed as a typing methodology with potential application for vaccine development5.

Penicillin remains the first choice antibiotic treatment for GAS infections, but an association with clindamycin is recommended in severe cases. In addition, both macrolides and lincosamides are important alternatives to β-lactam-allergic patients, although variable macrolide and lincosamide resistance rates can be found among GAS causing infections in different countries6.

In Europe and North America, after a decrease throughout most of the 20th century, a resurgence of invasive GAS infections (iGAS) was recorded in the late 1980s2. Since then, multiple studies have documented a high incidence of iGAS associated with high morbidity and mortality (https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/surv-reports.html)7,8. This was accompanied by a long-term high prevalence of an emm1 lineage also known as the virulent M1T1 clone, whose evolutionary pathway has been well documented9. However, upsurges of iGAS associated with specific lineages of other emm types have also been reported. A few examples are the dissemination of emm59 in the US and Canada since the second half of the 2000s decade10, the 2008–2009 upsurge of iGAS in the UK due to an emm3 lineage with an altered prophage profile11, and the spread of an emm89 clade lacking the hyaluronic acid capsule synthesis locus in North America and Europe since the 2000s12,13,14. Both the emm3 and emm89 epidemic lineages were associated with a change in the dominant profile of prophage-encoded genes relative to the previously dominant lineages of the respective emm types11,12, supporting the usefulness of methodologies like superantigen (SAg) gene profiling as complementary typing methods to further discriminate isolates sharing the same emm type15.

The molecular surveillance of GAS recovered from human infections worldwide is therefore crucial for providing information on possible shifts in clone prevalence with an impact on vaccine development, as well as for the early detection of clones with enhanced virulence, transmission, or antimicrobial resistance. Previous studies showed that the GAS population causing invasive disease in Portugal is genetically diverse, despite the dominance of the emm1 clone16,17,18. From 2000–2005 to 2006–2009, there was a decrease in the diversity of emm types, accompanied by a diversification of the SAg gene content of some of the dominant clones17. Here we report on the emm types, SAg gene profiles, and antimicrobial resistance of 381 iGAS isolates recovered in Portugal during 2010–2015.

Results

Demographic data

A total of 381 non-duplicate isolates were received (51 isolates in 2010, 70 in 2011, 62 in 2012, 50 in 2013, 68 in 2014, and 80 in 2015) (dataset available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3441765). The great majority of the isolates were recovered from blood (n = 330). Other isolate sources included pleural fluid (n = 23), ascitic fluid (n = 12), synovial fluid (n = 10), cerebrospinal fluid (n = 4), and bone biopsy (n = 2). From the 381 isolates, 193 (51%) were recovered from female patients. Patient age ranged between 1 day and 97 years (median 58 years). The majority of the isolates were recovered from adults (≥18 years, n = 295, 77%), mostly from those ≥65 years old (n = 151, 40%). Among children, the majority of the isolates were from patients ≤5 years old (n = 67, 18%).

Molecular typing

The 381 iGAS isolates presented a high genetic diversity, comprising 40 different emm types, 14 emm clusters or singletons, and 52 SAg profiles, all with Simpson’s index of diversity (SID) values > 0.8 (Supplementary Table S1).

Five emm types accounted for 63% of the isolates, namely emm1 (28%), emm89 (11%), emm3 (9%), emm12 (8%), and emm6 (7%) (Table 1). Although the majority of the emm clusters identified in this study were dominated by one emm type (Table 1 and Fig. 1), the cluster distribution did not directly reflect the prevalence of the respective dominant emm types due to the presence of multiple emm types in several clusters, including E3, E4, and E6.

Distribution of GAS isolates recovered from normally sterile sites in Portugal during 2010–2015 according to emm cluster and emm type. Numbers inside the bars represent the emm types included in each cluster. White bars include emm types with <5 isolates [E4: emm102 (n = 2), emm2, emm73, emm84, and emm169 (each n = 1); E3: emm118 (n = 2), emm9, emm82, and emm103 (each n = 1); E6: emm11 (n = 4), emm81 (n = 2), emm85, emm94, and emm99 (each n = 1); E1: emm78 (n = 2) and emm165 (n = 1); E2: emm90, emm110 (each n = 2), emm50, emm66, and emm104 (each n = 1)]. M5 and M6 are singletons belonging to clade Y. “Other” includes emm clusters or singletons with <5 isolates each [D4: emm70 (n = 2), emm33, and emm43 (each n = 1); D2: emm71 (n = 1); D3: emm123 (n = 1); M18: emm18 (n = 1)].

Among the studied isolates, emm1 (and, as such, cluster A-C3) and emm cluster E4 were slightly overrepresented among paediatric and adult patients, respectively (p = 0.013 and p = 0.025, respectively), and emm cluster E1 was more prevalent in males (p = 0.008). However, all these associations lost statistical significance after the false-discovery rate (FDR) correction.

In line with the results obtained in previous studies17,18, the chromosomal SAg genes speG and smeZ were detected in the great majority of isolates (n = 354 and 376, respectively), followed by speC (n = 190), speA (n = 167), speJ (n = 160), speK (n = 91), ssa (n = 89), speH (n = 64), speI (n = 58), speM (n = 33), and speL (n = 32) (Supplementary Table S2). With the exception of emm5, all emm types with >5 isolates included multiple SAg profiles (Table 1).

The absence of the hasABC locus encoding the GAS capsule biosynthesis pathway was used as a surrogate for the identification of the recently emerged acapsular emm89 clade12. Among the 42 iGAS isolates presenting emm89 in this study, only 3 (isolated in 2010 and 2011) were positive for the capsule locus.

Antimicrobial resistance

All 381 isolates were susceptible to penicillin, chloramphenicol, vancomycin, and linezolid. Fourteen isolates (4%) were resistant to erythromycin (Table 1), of which nine were constitutively resistant to clindamycin (cMLSB phenotype) and carried the erm(B) gene, while five presented inducible resistance to clindamycin (iMLSB phenotype), harbouring the erm(TR) gene. Despite the small number of macrolide resistant isolates, their genetic diversity was high [SID (CI95%) = 0.846 (0.755–0.937)], with six different emm types identified.

Tetracycline resistance was detected in 30 isolates (8%) (Table 1), of which 23 carried the tet(M) gene, 3 carried both tet(L) and tet(M), 3 harboured tet(O), and 1 presented tet(L) only (dataset available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3441765). Tetracycline-resistant isolates were also very diverse [19 different emm types, SID (CI95%) = 0.963 (0.937–0.989)]. Five isolates were also resistant to erythromycin, including two emm11 isolates carrying erm(B) and tet(M), and three emm77 isolates carrying erm(TR) and tet(O).

In agreement with previously studied periods17,18, during 2010–2015 bacitracin resistance remained restricted to an emm28 lineage expressing the cMLSB phenotype of macrolide resistance (n = 4, Table 1).

Two isolates presented intermediate resistance to levofloxacin (MIC = 4 and 6 µg/ml). Both belonged to emm28, were resistant to erythromycin, clindamycin (cMLSB), and bacitracin, and carried the mutation S79Y in the quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDR) of the parC gene. One emm89 isolate presented high-level levofloxacin resistance (MIC > 32 µg/ml) and carried mutation S79F in parC and mutation E85K in gyrA.

Discussion

The iGAS isolates recovered throughout Portugal between 2010 and 2015 were genetically diverse, with SID values similar to the ones obtained for iGAS isolates recovered during 2006–200917. Still, the five most prevalent emm types, namely emm types 1, 89, 3, 12, and 6, comprised 63% of the isolates, with emm1 persisting as the leading invasive emm type (28%). Twenty-one of the forty emm types identified in this study (94% of the isolates) are included in the 30-valent M protein-based vaccine currently under development. This vaccine could potentially cover up to 96% of the isolates of this study, considering the presumed cross-protection against a number of non-vaccine serotypes19. These results are in agreement with the overall scenario in Europe and the US in contemporary periods, although with some variations in the ranking of the top emm types7,8,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. In contrast, remarkable heterogeneity is found in the Southern hemisphere and developing regions, where the diversity of emm types is significantly higher, resulting in a much lower estimated coverage of the 30-valent vaccine27,28,29.

Since we have been following the molecular epidemiology of iGAS in Portugal from 2000 onwards16,17,18, the yearly distribution of emm types with ≥20 isolates in 2000–2015 was analysed over the 16 studied years (Fig. 2). For most emm types there were yearly fluctuations without any specific trend. However, an increasing trend was observed for emm1 (p = 0.008), emm75 (p < 0.001), and emm87 (p = 0.007), which remained significant after FDR correction. The increase in emm1 further reinforces the prolonged success of the contemporary emm1 clone in causing iGAS in temperate climate regions. In Portugal, this clone has been dominant among iGAS for at least 15 years and was shown to be overrepresented in isolates recovered from normally sterile sites compared to isolates from pharyngeal and skin and soft tissue infections17,18,30. In line with our results, in recent years, the prevalence of emm1 among iGAS in Europe and the US varied between 22% and 32%7,20,21,22,23,24,25; the exceptions being the lower prevalence in Finland (12%)8 and higher in Scotland, where this emm type accounted for 66% of iGAS in 2011–201526.

The increasing trend in emm75 is in agreement with the rise in prevalence of this emm type from 0.5% in 2006–2009 to 5% in 2010–2015 (p = 0.006), which was not significant after FDR correction. This increase in emm75 was somewhat surprising, since we previously found this emm type to be significantly underrepresented among iGAS when compared with pharyngeal isolates recovered in the same period in Portugal18. In agreement, an emm75 strain was recently selected for a controlled human infection model of GAS pharyngitis based on its limited virulence31. In our previous study including iGAS and pharyngitis isolates, a high diversity among emm75 isolates was observed18. Among the emm75 isolates from 2010–2015, five different SAg profiles were identified, but 13/19 isolates presented SAg25. Previously, only two emm75-SAg25 isolates had been identified in Portugal, both recovered from pharyngeal infections in the period of 2000–200518. The increasing trend in emm75 among iGAS could result from the emergence of this particular lineage from 2013 onwards. At present, it is not possible to know if this lineage is particularly prone to causing invasive disease or if it increased equally among non-invasive infections in Portugal.

The prevalence of emm87 has been gradually increasing among iGAS in Portugal, with no apparent new lineage emerging in recent years when considering SAg profiles, which remained the same (mostly SAg20). Isolates of emm87 have been associated with familial and hospital clusters of iGAS and proposed to be highly transmissible32,33, but have not been specifically associated with iGAS when compared with contemporary non-invasive isolates18,34.

In Portugal, the recent acapsular emm89 clade emerged among iGAS in 2007 and quickly outcompeted the previously circulating emm89 isolates carrying the hasABC locus12. Accordingly, among the 42 emm89 isolates recovered between 2010 and 2015, only 3 isolates carried the capsule locus (Fig. 3). The prevalence of emm89 among iGAS did not present an increasing trend, nor did it increase significantly in the period following the introduction of the new clade when compared with previous years, in contrast to what we reported among isolates from skin and soft tissue infections30. This indicates that the new clade was highly successful in outcompeting the previously circulating emm89 isolates in all infection types, but is not associated with an enhanced ability to cause infection in normally sterile sites.

Yearly distribution of invasive emm89 isolates with (filled bars) and without (open bars) the hasABC locus. Numbers inside the bars represent number of isolates. Data from 2000–2009 was previously published12.

Between 2000–2005 and 2006–2009 a diversification of SAg profiles within emm types 1, 28 and 44 was noted, as well as a shift in the dominant SAg profile among emm89 isolates that was correlated with the emergence of the acapsular clade12,17. The comparison of the SID of the SAg profiles identified within emm types with ≥5 isolates in each of the two most recent study periods (2006–2009 and 2010–2015) showed a significant diversification of SAg profiles for emm3 and emm6 (p = 0.009 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2). SAg8 was dominant among emm3 isolates in all studied periods, but up to 2009 only one isolate presented a different SAg profile (SAg53), while in 2010–2015 there were four isolates with SAg53 and five isolates with SAg9. Regarding emm6, up to 2008 all isolates presented SAg2. In 2009 SAg51 emerged and became the most common SAg profile in 2010–2015 (n = 9), followed by SAg2 (n = 8) and three other SAg profiles that emerged in this period, namely SAg72 (n = 5), SAg26 (n = 2), and SAg16 (n = 1). Further studies are needed to clarify if the isolates presenting the new SAg profiles within emm3 and emm6 emerged from the previously dominant emm3-SAg8 and emm6-SAg2 lineages by loss or gain of SAg genes, or if they represent distinct genetic clades that could underlie the rise in prevalence of both emm types during 2010–2012 (Fig. 2).

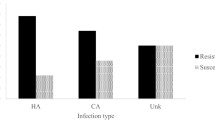

Erythromycin resistance (4%) decreased relative to the previously studied period of 2006–200917 (8%, p = 0.026) (Fig. 4). The overall decreasing trend in macrolide resistance recorded among invasive GAS in the period of 2000–2015 (p < 0.001) mirrors the one previously reported for isolates recovered from pharyngitis and skin and soft tissue infections30,35. Despite this decrease, the genetic diversity of the macrolide resistant isolates remained high.

Prevalence of erythromycin resistance and of macrolide resistance phenotypes among isolates recovered from invasive infections in Portugal during 2000–2015. The numbers below each period represent the total number of iGAS isolates recovered. Data from 2000–2005 and 2006–2009 was previously published17,18.

The genetic determinants of tetracycline resistance are often horizontally transferred together with macrolide resistance determinants in the same mobile genetic elements36. Among the 30 resistant iGAS isolates from 2010–2015 in Portugal (8%), only 5 were also resistant to erythromycin, 3 of which belong to a lineage of emm77-SAg30 isolates carrying erm(TR) and tet(O) that had not been previously identified among iGAS in Portugal. Although the tetracycline resistance rate did not decrease significantly relative to 2006–2009, an overall decreasing trend was observed during 2000–2015 (p = 0.002).

A limitation of this study is that isolate submission was voluntary, without any audit, preventing us from controlling any possible bias on the selection of the isolates submitted by each lab. Although we expect that not all isolates recovered from iGAS were submitted, the inclusion of 40 laboratories distributed throughout the country provided us with a representative collection of isolates, limiting the impact that any strain selection bias could have on the results and conclusions of the study. Screening of SAg and resistance genes by PCR alone presents another limitation given the possible occurrence of false-positives and false-negatives. In order to reduce the potential impact of this limitation on the results, we have used carefully optimised multiplex PCR reaction conditions, including both positive and negative controls in each reaction15,17. The high correlation between SAg profiles and the results of other typing methods15, as well as between the resistance genotypes determined and the respective resistance phenotypes and lineages, supports the accuracy of the PCR results.

This is the first study providing detailed molecular epidemiological data on iGAS infections in a Southern European country in the current decade. The results suggest that the emm type and emm cluster composition of GAS causing invasive disease in Portugal has remained stable since the second half of the 2000s decade, presenting no major changes in prevalence of individual emm types or clusters17. However, there have been changes in the SAg gene content within multiple emm types, which may reflect the ongoing horizontal transfer of phage-encoded genes between GAS lineages, or the emergence of new genetic clades. In some cases, these changes seem to be associated with temporal fluctuations in the prevalence of the respective emm types. Streptococcal SAgs can directly contribute to the emergence of new successful lineages through their role in virulence and the immune response37. On the other hand, changes in SAg gene content reflect the loss and acquisition of prophages that often carry other virulence factors or antimicrobial resistance determinants that could also contribute to the success of those lineages38. Given that the emergence of clades with increased success within previously circulating emm types has been reported in multiple occasions11,13, the continued molecular surveillance of GAS infections using methods capable of further discriminating isolates sharing the same emm type is critical for the identification of the emergence of novel lineages which could drive increases in iGAS disease.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial isolates

Forty clinical microbiology laboratories distributed throughout Portugal were asked to submit, on a voluntary basis, all GAS isolated from normally sterile sites between January 2010 and December 2015. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Centro Académico de Medicina de Lisboa. Since only anonymized demographic patient information was used and the samples used were collected within the normal diagnostic procedure by the attending physician, the study was exempt from obtaining written informed consent from the patients. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Strains were identified by the submitting laboratories and confirmed in our laboratory by colony morphology, β-haemolysis, and the presence of the characteristic Lancefield group A antigen (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK).

Molecular typing

The emm type was determined for all isolates according to the protocols and recommendations of the CDC (http://www.cdc.gov/streplab/groupa-strep/emm-typing-protocol.html), and the first 240 bases of each sequence were compared to the sequences deposited in the CDC emm database using the CDC BLAST tool (http://www2a.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strepblast.asp). The presence of 11 SAg genes (speA, speC, speG, speH, speI, speJ, speK, speL, speM, smeZ, and ssa) was tested by two previously described multiplex PCR reactions, using the chromosomally encoded genes speB and speF as positive control fragments15. All emm89 isolates were screened for the presence of the has locus by PCR12.

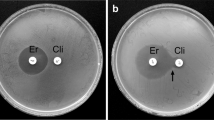

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Susceptibility tests were performed for all isolates by disk diffusion according to the guidelines and interpretative criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)39, using the following disks (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK): penicillin, vancomycin, erythromycin, tetracycline, levofloxacin, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, and linezolid. Macrolide resistance phenotypes were determined by the double-disk test39. E-test strips (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and CLSI interpretative criteria39 were used for MIC determination in levofloxacin non-susceptible isolates and in all cases of intermediate susceptibility by disk diffusion. Susceptibility to bacitracin was determined using BD BBLTM TaxoTM A Disks (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA).

Detection of genetic determinants of antimicrobial resistance

The screening for the genetic determinants of resistance to macrolides, tetracycline and fluoroquinolones was performed as previously described17. Briefly, erythromycin-resistant isolates were tested for the presence of the mef, erm(A), and erm(B) genes by multiplex PCR, followed by a second PCR to distinguish between mef(A) and mef(E) in mef-positive isolates. Tetracycline-resistant isolates were PCR-screened for the presence of the tet(K), tet(L), tet(M), and tet(O) genes. For levofloxacin non-susceptible isolates, the QRDRs of the gyrA and parC genes were amplified by PCR and sequenced.

Statistical analysis

The diversity of the isolates according to different typing methods was evaluated using the SID with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI95%)40, calculated using an online tool (http://www.comparingpartitions.info). Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test and odds ratios were used to identify significant pairwise associations. The Cochran-Armitage test was used to evaluate trends. The p-values for multiple tests were corrected using the FDR linear procedure41. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3441765.

References

Carapetis, J. R., Steer, A. C., Mulholland, E. K. & Weber, M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 685–694 (2005).

Walker, M. J. et al. Disease manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms of group A Streptococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27, 264–301 (2014).

Fischetti, V. A. Vaccine approaches to protect against group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Microbiol Spectr 7 (2019).

Beall, B., Facklam, R. & Thompson, T. Sequencing emm-specific PCR products for routine and accurate typing of group A streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34, 953–958 (1996).

Sanderson-Smith, M. et al. A systematic and functional classification of Streptococcus pyogenes that serves as a new tool for molecular typing and vaccine development. J Infect Dis 210, 1325–1338 (2014).

Silva-Costa, C., Friães, A., Ramirez, M. & Melo-Cristino, J. Macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes: prevalence and treatment strategies. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 13, 615–628 (2015).

Naseer, U., Steinbakk, M., Blystad, H. & Caugant, D. A. Epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcal infections in Norway 2010–2014: A retrospective cohort study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 35, 1639–1648 (2016).

Smit, P. W. et al. Epidemiology and emm types of invasive group A streptococcal infections in Finland, 2008–2013. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 34, 2131–2136 (2015).

Nasser, W. et al. Evolutionary pathway to increased virulence and epidemic group A Streptococcus disease derived from 3,615 genome sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E1768–1776 (2014).

Fittipaldi, N. et al. Full-genome dissection of an epidemic of severe invasive disease caused by a hypervirulent, recently emerged clone of group A. Streptococcus. Am. J. Pathol. 180, 1522–1534 (2012).

Afshar, B. et al. Enhanced nasopharyngeal infection and shedding associated with an epidemic lineage of emm3 group A Streptococcus. Virulence 8, 1390–1400 (2017).

Friães, A. et al. Emergence of the same successful clade among distinct populations of emm89 Streptococcus pyogenes in multiple geographic regions. mBio 6, e01780–15 (2015).

Turner, C. E. et al. Emergence of a new highly successful acapsular group A Streptococcus clade of genotype emm89 in the United Kingdom. mBio 6, e00622–15 (2015).

Zhu, L. et al. A molecular trigger for intercontinental epidemics of group A Streptococcus. Journal of Clinical Investigation 125, 3545–3559 (2015).

Friães, A., Pinto, F. R., Silva-Costa, C., Ramirez, M. & Melo-Cristino, J. Superantigen gene complement of Streptococcus pyogenes-relationship with other typing methods and short-term stability. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32, 115–125 (2013).

Friães, A., Ramirez, M. & Melo-Cristino, J. & Portuguese Group for the Study of Streptococcal Infections. Nonoutbreak surveillance of group A streptococci causing invasive disease in Portugal identified internationally disseminated clones among members of a genetically heterogeneous population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 2044–2047 (2007).

Friães, A., Lopes, J. P., Melo-Cristino, J. & Ramirez, M. & Portuguese Group for the Study of Streptococcal Infections. Changes in Streptococcus pyogenes causing invasive disease in Portugal: Evidence for superantigen gene loss and acquisition. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303, 505–513 (2013).

Friães, A., Pinto, F. R., Silva-Costa, C., Ramirez, M. & Melo-Cristino, J. Group A streptococci clones associated with invasive infections and pharyngitis in Portugal present differences in emm types, superantigen gene content and antimicrobial resistance. BMC Microbiol. 12, 280 (2012).

Dale, J. B., Penfound, T. A., Chiang, E. Y. & Walton, W. J. New 30-valent M protein-based vaccine evokes cross-opsonic antibodies against non-vaccine serotypes of group A streptococci. Vaccine 29, 8175–8178 (2011).

Meehan, M., Murchan, S., Gavin, P. J., Drew, R. J. & Cunney, R. Epidemiology of an upsurge of invasive group A streptococcal infections in Ireland, 2012–2015. J. Infect. 77, 183–190 (2018).

Imöhl, M., Fitzner, C., Perniciaro, S. & van der Linden, M. Epidemiology and distribution of 10 superantigens among invasive Streptococcus pyogenes disease in Germany from 2009 to 2014. PLoS One 12, e0180757 (2017).

Olafsdottir, L. B. et al. Invasive infections due to Streptococcus pyogenes: seasonal variation of severity and clinical characteristics, Iceland, 1975 to 2012. Euro Surveill. 19, 5–14 (2014).

Lambertsen, L. M., Ingels, H., Schønheyder, H. C. & Hoffmann, S. & Danish Streptococcal Surveillance Collaboration Group 2011. Nationwide laboratory-based surveillance of invasive beta-haemolytic streptococci in Denmark from 2005 to 2011. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, O216–223 (2014).

Nelson, G. E. et al. Epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcal infections in the United States, 2005–2012. Clin. Infect. Dis. 63, 478–486 (2016).

Chochua, S. et al. Population and whole genome sequence based characterization of invasive group A streptococci recovered in the United States during 2015. mBio 8, e01422–17 (2017).

Lindsay, D. S. J. et al. Circulating emm types of Streptococcus pyogenes in Scotland: 2011–2015. Journal of Medical Microbiology 65, 1229–1231 (2016).

Baroux, N. et al. The emm-cluster typing system for group A Streptococcus identifies epidemiologic similarities across the Pacific region. Clin Infect Dis. 59, e84–e92 (2014).

Williamson, D. A. et al. Comparative M-protein analysis of Streptococcus pyogenes from pharyngitis and skin infections in New Zealand: Implications for vaccine development. BMC Infectious Diseases 16, 561 (2016).

Abraham, T. & Sistla, S. Decoding the molecular epidemiology of group A Streptococcus - an Indian perspective. J. Med. Microbiol. 68, 1059–1071 (2019).

Pato, C., Melo-Cristino, J., Ramirez, M. & Friães, A. & Portuguese Group for the Study of Streptococcal Infections. Streptococcus pyogenes causing skin and soft tissue infections are enriched in the recently emerged emm89 clade 3 and are not associated with abrogation of CovRS. Front Microbiol 9, 2372 (2018).

Osowicki, J. et al. A controlled human infection model of group A Streptococcus pharyngitis: which strain and why? mSphere 4 (2019).

Flores, A. R., Luna, R. A., Runge, J. K., Shelburne, S. A. & Baker, C. J. Cluster of fatal group A streptococcal emm87 infections in a single family: molecular basis for invasion and transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 215, 1648–1652 (2017).

Montes, M., Tamayo, E., Oñate, E., Pérez-Yarza, E. G. & Pérez-Trallero, E. Outbreak of Streptococcus pyogenes infection in healthcare workers in a paediatric intensive care unit: transmission from a single patient. Epidemiol. Infect. 141, 341–343 (2013).

Ekelund, K. et al. Variations in emm type among group A streptococcal isolates causing invasive or noninvasive infections in a nationwide study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 3101–3109 (2005).

Silva-Costa, C., Ramirez, M. & Melo-Cristino, J. & Portuguese Group for Study of Streptococcal Infections. Declining macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes in Portugal (2007–13) was accompanied by continuous clonal changes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 2729–2733 (2015).

Varaldo, P. E., Montanari, M. P. & Giovanetti, E. Genetic elements responsible for erythromycin resistance in streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 343–353 (2009).

Shannon, B. A., McCormick, J. K. & Schlievert, P. M. Toxins and superantigens of group A streptococci. Microbiol Spectr 7 (2019).

McShan, W. M., McCullor, K. A. & Nguyen, S. V. The bacteriophages of Streptococcus pyogenes. Microbiol Spectr 7 (2019).

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI document M100. (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Pennsylvania, USA, 2018).

Carriço, J. A. et al. Illustration of a common framework for relating multiple typing methods by application to macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 2524–2532 (2006).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Acknowledgements

Joana P. Lopes, Soraia Guerreiro and Ana Catarina Mendes are gratefully thanked for technical support in the characterization of the isolates. This work was partly supported by UID/BIM/50005/2019, project funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT)/Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (MCTES) through Fundos do Orçamento de Estado. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

A.F. performed the experiments. P.G.S.S.I. collected data. A.F. and M.R. analysed and interpreted the data. A.F., J.M.-C. and M.R. were involved in the conception and design of the study, as well as in drafting the manuscript. A.F., J.M.-C., M.R. and P.G.S.S.I. were involved in revising the paper critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.M.-C. has received research grants administered through his university and received honoraria for serving on the speakers bureaus of Pfzer and Merck Sharp and Dohme. M.R. has received honoraria for serving on the speakers bureau of Pfizer and for consulting for GlaxoSmithKline and Merck Sharp and Dohme. The other authors declare no conflict of interest. No company or financing body had any interference in the decision to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A comprehensive list of consortium members appears at the end of the paper

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Friães, A., Melo-Cristino, J., Ramirez, M. et al. Changes in emm types and superantigen gene content of Streptococcus pyogenes causing invasive infections in Portugal. Sci Rep 9, 18051 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54409-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54409-2

This article is cited by

-

Pathogenesis, epidemiology and control of Group A Streptococcus infection

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2023)

-

Molecular epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of group a streptococcus recovered from patients in Beijing, China

BMC Infectious Diseases (2020)

-

Epidemiological analysis of Group A Streptococcus infections in a hospital in Beijing, China

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.