Abstract

Soft corals often constitute one of the major benthic groups of coral reefs. Although they have been documented to outcompete reef-building corals following environmental disturbances, their physiological performance and thus their functional importance in reefs are still poorly understood. In particular, the acclimatization to depth of soft corals harboring dinoflagellate symbionts and the metabolic interactions between these two partners have received little attention. We performed stable isotope tracer experiments on two soft coral species (Litophyton sp. and Rhytisma fulvum fulvum) from shallow and upper mesophotic Red Sea coral reefs to quantify the acquisition and allocation of autotrophic carbon within the symbiotic association. Carbon acquisition and respiration measurements distinguish Litophyton sp. as mainly autotrophic and Rhytisma fulvum fulvum as rather heterotrophic species. In both species, carbon acquisition was constant at the two investigated depths. This is a major difference from scleractinian corals, whose carbon acquisition decreases with depth. In addition, carbon acquisition and photosynthate translocation to the host decreased with an increase in symbiont density, suggesting that nutrient provision to octocoral symbionts can quickly become a limiting factor of their productivity. These findings improve our understanding of the biology of soft corals at the organism-scale and further highlight the need to investigate how their nutrition will be affected under changing environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mutualistic symbioses between cnidarians and photosynthetic dinoflagellates of the family Symbiodiniaceae are widespread in marine environments1. In coral reef ecosystems, this association is the backbone for the growth and survival of corals surrounded by oligotrophic waters that hardly provide any exogenous nutrients. Indeed, the dinoflagellate symbionts of scleractinian corals translocate a large proportion of their photosynthetically fixed carbon compounds to the coral host for its own nutrition, growth, reproduction and energetic needs2. The percentage of carbon translocation can be as high as 90% in well-lit shallow waters3,4, and can remain high in mesophotic environments5. However, the total amount of autotrophically-acquired carbon generally decreases from shallow to deep reef environments through a reduced productivity of dinoflagellate symbionts5. Simultaneously, the coral host becomes more dependent on heterotrophic food sources and it is the plasticity between host heterotrophy and symbiont autotrophy that allows the association to thrive in such contrasting reef environments6. So far, our understanding of coral holobiont performance and host-symbiont metabolic interactions under different environmental conditions is limited to studies on scleractinian corals, while there is very little information available for other prominent members of reef systems such as soft corals (Alcyonacea).

Soft corals often constitute the second major benthic group of reef ecosystems7. They can thrive with relative high abundance and diversity under very different environmental conditions ranging from turbid to clear-water8,9 or from shallow to mesophotic reef environments10. Similarly to scleractinian corals, a large proportion (≥50%) of soft coral taxa is associated with Symbiodiniaceae in the Eastern Pacific, Caribbean, Red Sea and Great Barrier Reef7. There is evidence showing that the abundance of soft coral populations maintained or increased in most regions worldwide whereas scleractinian coral cover generally declined over the last decades11,12, due to increased sea surface temperatures, eutrophication and pollution. This is usually explained by a greater nutritional plasticity of soft corals, which are considered as mixotrophic species13. They can therefore acquire nutrients through the autotrophic activity of the symbionts, but also through the heterotrophic capacity of the host8,13. Evidence in the literature demonstrates that feeding has a positive effect on coral tissue, enhancing the growth of both partners of the symbiosis14. In addition, feeding can play a central role in maintaining physiological function when autotrophy is reduced15. The lower dependency of soft corals on autotrophy, compared to scleractinian corals, has been deduced from few measurements performed in shallow water conditions (0–20 m)7,13,16,17,18. Therefore, knowledge gaps exist for the main autotrophic physiological processes in soft corals thriving under different environmental conditions. The few studies which have dealt with their carbon budget observed highly variable contributions of photosynthetically fixed carbon provided by the symbionts to the host, with carbon translocation rates ranging from 10% in Capnella gabonensis to 75% in Sinularia flexibilis19,20,21,22. In addition, different normalization metrics for physiological processes in soft and scleractinian corals often hinder comparisons of the trophic characteristics between the two groups.

While tropical soft corals are considered reef engineers which create habitats for other reef species7,23, little comprehensive data exist on their trophic ecology, and therefore on their functional role as primary producers and carbon sinks within the reef ecosystem8,13,24,25. Since autotrophic carbon acquisition is a key factor shaping coral productivity, physiology, and ecology, and partly explains coral success or failure under changing environmental conditions, more studies should be dedicated to better understand the autotrophic capacity of soft corals. Therefore, the present study aims to assess the carbon fluxes between dinoflagellate symbionts and host of two common soft coral species (Litophyton sp. and Rhytisma fulvum fulvum) from shallow and mesophotic reefs of the Gulf of Eilat. For this purpose, we used stable isotope tracers (13C-bicarbonate) to measure the rates of carbon fixed, exchanged and lost by the shallow and mesophotic symbiotic associations under their natural photosynthetically active irradiance (PAR) levels. Importantly, we also compare our results with those of scleractinian coral species by applying a standardized normalization metric for all parameters26,27.

Results

Physiological measurements

The dinoflagellate-host association was species-specific. Litophyton sp. harbored Symbiodinium sp. (formerly Symbiodinium clade A28) whereas R. f. fulvum was associated with Cladocopium thermophilum (formerly Symbiodinium thermophilum clade C328,29), regardless of the depth investigated. Symbiodiniaceae density, normalized to AFDW, was two-fold higher in Litophyton sp. than in R. f. fulvum at both depths and was for both species always higher in shallow than in mesophotic con-specifics (Fig. 1a, Table S1). For both species, total chlorophyll concentrations (per AFDW) were significantly higher for mesophotic corals (Fig. 1b, Table S1). Also, symbionts contained significantly more chlorophyll per cell in mesophotic corals (2.8·10−6 ± 3.2·10−7 µg cell−1 for Litophyton sp. and 7.5·10−6 ± 4.9·10−7 µg cell−1 for R. f. fulvum, Table S1) as compared to shallow corals (1.6·10−6 ± 1.5·10−7 µg cell−1 for Litophyton sp. and 4.2·10−6 ± 1.2·10−6 µg cell−1 for R. f. fulvum, Table S1).

Physiological and tissue descriptors measured in the soft coral species investigated. For panels (a–b) and (c), data are normalized to ash-free dry weight (AFDW). (a) Symbiodiniaceae density. (b) Total chlorophyll concentration. (c) Autotrophic carbon acquisition. (d) Autotrophic carbon acquisition per Symbiodiniaceae cell. Error bars represent standard error. There were significant differences between species and depths for (a), between depths for (b–d), and between species for (c) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Autotrophic carbon acquisition, estimated using 13C-bicarbonate incorporation over 5 h under maximal irradiance (PC, expressed in µg C g−1 AFDW h−1), was significantly different between the two coral species, with Litophyton sp. exhibiting higher Pc rates than R. f. fulvum (Fig. 1c, Table S1). When normalized to symbiont cells, Pc rates were significantly different between depths, with higher values obtained in mesophotic conditions (Fig. 1d, Table S1). Respiration rates (Rc, expressed in µg C g−1 AFDW h−1) were similar between depths for R. f. fulvum (347 ± 45 and 489 ± 47 in shallow and mesophotic conditions, respectively), whereas they were two-fold lower for mesophotic (148 ± 47) than shallow (406 ± 18) nubbins of Litophyton sp. (Table S1, Tukey HSD p < 0.01). While symbiont respiration accounted for less than 1% of the holobiont respiration for Litophyton sp. in both depths, symbiont respiration accounted ca. 6% and 4% to holobiont respiration for mesophotic and shallow R. f. fulvum, respectively.

Carbon budget

After the pulse period (5 h), both species exhibited significant differences in their carbon budget between depths (Fig. 2a–d, Tables S1 and S2). Overall, rates of photosynthate translocation were lower in Litophyton sp. at both depths (36% to 60% of the total fixed carbon) compared to R. f. fulvum (85%), and symbionts of Litophyton sp. retained four to five times more carbon than those of R. f. fulvum (Fig. 2b–d, Table S1). However, no difference was observed in the rate of carbon assimilated by the host between depths and species (134–150 µg C g−1 AFDW h−1). For Litophyton sp. from mesophotic depth, symbionts translocated less carbon to the host (36% versus 60%) and less carbon was lost by the holobiont (19% versus 44%) as compared to nubbins from shallow depth. On the contrary, photosynthate translocation (85%) and carbon loss (64–70%) were comparable between shallow and mesophotic R. f. fulvum corals.

Carbon budgets obtained after the 5 hours pulse period in the soft coral species investigated. (a) Shallow Litophyton sp. (b) Mesophotic Litophyton sp. (c) Shallow Rhytisma fulvum fulvum. (d) Mesophotic Rhytisma fulvum fulvum. Symbionts are represented by a green circle. PC = autotrophic carbon acquisition. ρS = carbon assimilated in Symbiodiniaceae. ρH = carbon assimilated by the coral host. TS = translocation of photosynthates. CLS = carbon lost by the symbionts through respiration. CLH = carbon lost by the host through respiration. PC and carbon fluxes are expressed in µg C g−1AFDW h−1.

After the chase period (24 h), the carbon budget of both species was clearly species-specific but without depth-specific differences (Fig. 3a–d, Table S1). In Litophyton sp., symbiont cells assimilated half of the photosynthesized carbon and translocated only 47% to the coral host in both shallow and mesophotic colonies (Fig. 3a–d, Table S1). On the contrary, symbionts in R. f. fulvum translocated 86–92% of the photosynthetically fixed carbon to the host and assimilated only 4–11% of this carbon for their own energetic needs. Consequently, significant differences were evident between the two species for the rates of carbon 1) translocated (up to one third lower in Litophyton sp. than in R. f. fulvum), 2) retained in the symbionts (ten-fold higher in Litophyton sp. than in R. f. fulvum) and 3) lost from the symbiotic association (two-fold lower in Litophyton sp. than in R. f. fulvum) (Fig. 3a–d, Table S1).

Carbon budgets obtained after the 24 hours chase period in the soft coral species investigated. (a) Shallow Litophyton sp. (b) Mesophotic Litophyton sp. (c) Shallow Rhytisma fulvum fulvum. (d) Mesophotic Rhytisma fulvum fulvum. Symbionts are represented by a green circle. ρS = carbon assimilated in Symbiodiniaceae. ρH = carbon assimilated by the coral host. TS = translocation of photosynthetates. CLS = carbon lost by the symbionts through respiration. CLH = carbon lost by the host through respiration and mucus production. Carbon fluxes are expressed in µg C g−1AFDW h−1.

Relationship between Symbiodiniaceae density and carbon flux

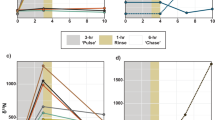

Our results show that in the two coral species at both depths the carbon acquisition per symbiont cell exponentially decreased with increasing symbiont density (Fig. 4a). In addition, we found a positive linear correlation between symbiont cell carbon acquisition and translocation (Fig. 4b).

Relationships between Symbiodiniaceae density and carbon fluxes of the soft coral species investigated. (a) Exponential relationship between carbon acquisition (PC) per cell and density of Symbiodiniaceae cells of Litophyton sp. and Rhytisma fulvum fulvum (R² = 0.78, y = 4.7087x−0.744). (b) Orthogonal regressions between carbon acquisition (PC) per cell and photosynthates translocation of Symbiodiniaceae cells of Litophyton sp. (R² = 0.60, y = 4.8964x − 1.7547) and Rhytisma fulvum fulvum (R² = 0.99, y = 1.1818x − 0.0091). AFDW = ash-free dry weight.

Discussion

This study shows that the functioning of the coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis in soft corals holds some different characteristics to that in many scleractinian corals, and that the two groups are differently acclimatized to depth. The two investigated soft coral species maintained an equivalent carbon acquisition from shallow to poorly-lit mesophotic habitats, while carbon acquisition of scleractinian corals generally decreases with depth. This autotrophic efficiency, combined with putative high heterotrophic capacities, may provide soft corals with an ecological advantage in the upper Red Sea mesophotic reefs10. In addition, the results show that carbon acquisition and translocation rates per symbiont cell were negatively correlated with the symbiont density within the host tissue, with a higher assimilation of carbon in symbiont biomass under high symbiont density. However, the rates at which carbon was translocated to and assimilated by the host were unaffected, indicating that dense symbiont populations can remain mutualistic.

Our findings indicate that the mean autotrophic carbon acquisition in both soft coral species (measured during 5 h and using 13C-labelling) remained stable from shallow to mesophotic environments, which suggests that soft corals are either photo-limited in shallow waters or well photo-acclimatized to depth (Fig. 5). This is in agreement with previous observations13 that maximal photosynthetic rates of several soft coral species from the Great Barrier Reef were measured at 20 m depth rather than in shallower waters (Table 1). Such constant carbon acquisition along the depth gradient is surprising in comparison to the general patterns observed in scleractinian corals. Most scleractinian corals experience a significant decrease in rates of carbon acquisition with depth, although this physiological parameter has been poorly investigated in mesophotic environments5,30,31. However, a recent study, which investigated the photosynthetic performance of the mesophotic coral Euphyllia paradivisa, found a high photosynthetic capacity of this coral species under low light conditions32.

Metabolic interactions between soft corals and their dinoflagellate symbionts. (a) Shallow Litophyton sp. (b) Mesophotic Litophyton sp. (c) Shallow Rhytisma fulvum fulvum. (d) Mesophotic Rhytisma fulvum fulvum. Boxes and arrows are indicative of differences in density and fluxes. Color intensity of symbionts corresponds to chlorophyll concentration levels. PC = autotrophic carbon acquisition.

Pigment content, symbiont density and symbiont genus are generally involved in shaping the photo-acclimatization of the coral symbiosis from shallow to mesophotic environments. Our results highlight for the two soft coral species a host-specific Symbiodiniaceae genus that remained stable along the depth profile up to 40 m depth. Litophyton sp. was associated with Symbiodinium sp., as previously reported (formerly Symbiodinium clade A33,34), while R. f. fulvum was rather associated with Cladocopium sp., in agreement with studies performed in the Red Sea (formerly Symbiodinium clade C33), or the Great Barrier Reef35,36. Such clade specificity is assumed to be persistent both in space and time in octocorals37,38. Thus, acclimatization of the soft corals to low light levels was independent of the symbiont genus, but potentially driven by higher concentrations of total chlorophyll per AFDW and per symbiont cell in mesophotic corals (Fig. 1b), which maximize the light harvesting capacity of the cells under low light levels5,39. In addition, both species exhibited a decreased symbiont density in mesophotic as compared to shallow colonies which is likely another adaptation to depth by reducing self-shading under reduced PAR40,41. A lower symbiont density also reduces the competition for inorganic nutrient supply42. It has been demonstrated that mesophotic scleractinian corals can display several strategies to acclimatize to low light levels, such as modifications in the organization of photosynthetic apparatus (shift to a PSII-based system, including additional photosynthetic antenna30), modifications in the organization of antenna (growth of specialized paracrystalline light-harvesting antenna domains43), or the synthesis of fluorescent pigments by the host (that can perform wavelength transformation to facilitate light penetration44); however, these strategies remain to be further investigated in soft corals.

The autotrophic carbon acquisition to respiration ratios (PC/RC) of Litophyton sp. ranged from 1 to 2 from shallow to mesophotic depths, the latter value being above the conservative threshold for net autotrophy (PC/RC > 1.5). Considering that the solar radiation level in November is one of the lowest annual levels45, the data suggest that Litophyton sp. is mostly an autotrophic species. On the contrary, PC/RC ratios of R. f. fulvum in November were always below compensation (PC/RC = 1) even when considering a maximal autotrophic carbon acquisition rate sustained for 12 h. This strongly suggests that this species relies, at least in winter, on heterotrophy to sustain its daily respiratory needs. The difference in PC/RC between the two species may be due to their different growth shapes and different micro-morphological features of the polyps. Two recent studies on gorgonian octocorals, indeed highlighted a correlation between host morphology, polyp size and productivity17,18, thereby corroborating the first observations of Porter (1976)46.

Symbiont cell carbon acquisition was negatively correlated with symbiont density in both investigated soft coral species and decreased exponentially as soon as the symbiont density increased. Although this pattern is first described on soft corals in this study, similar observations were reported with gorgonian octocorals18 and scleractinian corals47, and might be due to a host-dependent regulation of light and nutrient ressources47, or a self-shading of the symbionts42.

Our results also highlight a positive correlation between carbon acquisition and carbon translocation rates per symbiont cell, similarly to a previous study on scleractinian corals48. In Litophyton sp., a low carbon acquisition per cell corresponded to a high symbiont density and consequently, symbiont cells assimilated more carbon for their own metabolism rather than translocating it to the host (50% translocation). In contrast, the symbionts in R. f. fulvum translocated significantly more carbon (80 to 90% translocation) to the host, likely due to their lower abundancy and increased rates of carbon acquisition per cell. Carbon translocation rates of >80% have also been reported for other coral species2,3,4. For example, Scheufen et al.47 measured highest productivity rates in corals during the very oligotrophic summer season despite seasonally reduced symbiont density. This may also imply a high carbon translocation to the host that is essential when exogenous food sources are scarce.

Differences in cell-specific carbon assimilation and translocation rates may not only be related to the symbiont density but also to the symbiont genus. Indeed, Symbiodinium sp. (associated with Litophyton sp. here) is known to translocate less carbon to its host as compared to Cladocopium sp. (associated with R. fulvum fulvum here)48,49,50. However, an important observation is that the lower percentage of carbon translocation in Litophyton sp. is not indicative of a shift towards symbiont parasitism50, as the carbon translocation to the host still exceeded the metabolic costs for holobiont respiration. In R. f. fulvum, due to the low symbiont density, an increased translocation rate per cell was needed to transfer the same amount of carbon to the host. In addition, the percentage of carbon lost by the host was lower in Litophyton sp. than in R. f. fulvum, compensating for the lower percentage of carbon translocated from the symbionts. As a consequence, the rates at which carbon was retained in the host were constant between species and depths (between 13% and 19% of the photosynthesized carbon, or 93 to 138 µg C g−1 AFDW h−1). Assimilation rates of 10 to 20% of the photosynthesized carbon by the animal host seems to be a general feature in corals4,5.

Soft and scleractinian corals therefore seem to exhibit a different trend of carbon acquisition along the depth gradient, although more investigations with different scleractinian and soft coral species are still needed. In order to compare carbon fixation per biomass between soft and scleractinian corals, we used data previously obtained on the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata sampled at the exact same location, depths and month5 (Table S3) and normalized the rates to AFDW. The estimates we obtained show that soft corals fix less carbon per biomass as compared to S. pistillata at shallow depth in November (estimation of 2426 µg C g−1 AFDW h−1 for S. pistillata versus 554–958 µg C g−1 AFDW h−1), although soft corals contain comparable or higher dinoflagellate density51 and chlorophyll content per biomass (Table S3) than scleractinian corals. However, in deeper environments, soft corals tend to fix carbon per biomass at similar or even higher rates (estimation of 555 µg C g−1 AFDW h−1 for S. pistillata versus 710–829 µg C g−1 AFDW h−1 for R. f. fulvum and Litophyton sp.). This may indicate that in shallow waters, soft corals have particularly less fixed carbon available to maintain or grow their biomass as compared to scleractinian corals. Morphological characteristics of the host, which have an impact on the diffusion and transmission of light to the symbionts, may explain differences in carbon acquisition in shallow water corals. Soft corals lack a calcium carbonate skeleton, contrary to scleractinian corals, and only possess sclerites as calcified structures. However, skeletons present light scattering abilities, which enhance light absorption efficiency of the symbionts (e.g., Enríquez et al.)52. Although characteristics of sclerites and tissues remain to be investigated to understand the potential light amplification and dispersion in soft corals, we hypothesized that they would affect the light environment of the symbionts to a lesser extent than skeletons do in scleractinian corals. In addition, soft corals have a thick coenenchyme and exhibit a low ratio of colony surface area to volume, which does not favor light exposure and gas or nutrient exchange through the epidermal tissue53. Finally, the variability of their hydroskeleton allows soft corals to contract and expand their tissue. Tissue contraction removes symbionts from the tissue surface, thereby higher irradiance is required to reach the symbionts and to achieve photosynthetic compensation and saturation.

Understanding nutritional ecology of octocorals is still in its infancy. The common belief is that octocorals are more heterotrophic than scleractinian corals, because of their low carbon acquisition in surface waters, and because their morphology is more suited for heterotrophy7. Two recent studies on Caribbean gorgonian octocorals have observed a possible correlation between host morphology and symbiont performance17,18. Octocorals with thin branches and small polyps can be more autotrophic as compared to those with a massive shape and large polyps. In our work, a different degree of autotrophy was demonstrated for the two investigated soft coral species, which might be linked to morphological traits. The arborescent shape of Litophyton sp. may enhance the exposure of symbionts to light and thus favour autotrophy compared to the mat-forming shape of R. f. fulvum. In addition, our results strongly support the view that high symbiont density results in lower cell-specific carbon translocation and acquisition. However, soft corals with high symbiont densities (Litophyton sp.) reached similar carbon translocation than those with low symbiont density. Further work involving various soft coral species, growth-shapes and symbiont-specificities will be essential to provide more insight into the physiology and trophic ecology of octocorals thriving along environmental gradients.

Material and Methods

Soft coral collection and experimental setup

The study was conducted in November 2017 at the Inter-University Institute for Marine Science (IUI), Gulf of Eilat. Experiments were performed with two soft coral species harboring dinoflagellate symbionts, Litophyton sp. (Forskål, 1775) and Rhytisma fulvum fulvum (Forskål, 1775) belonging to the Alcyoniidae family.

Ten colonies per species were sampled on the reef adjacent to the IUI (29°51′N, 34°94′E) at 8 m and 40 m depth, respectively, to generate a total of 40 nubbins per species (two nubbins per colony). Nubbins were allowed to recover for ten days in open-water cages placed at the original collection site before being brought back to the Red Sea Simulator facility54. There, nubbins were allocated to three different outside aquaria per species and depth. All aquaria were continuously supplied with water directly pumped from the reef and were exposed to the natural diurnal light cycle. Furthermore, aquaria were shaded with several layers of mesh clothes to adjust daily maximum light levels to the maximum irradiance measured at the corresponding depth. Thus, all nubbins were maintained under natural diurnal variation in irradiance and received the depth-corresponding in situ maximum irradiance at noon. Levels of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) were obtained from the Israel National Monitoring program of the Gulf of Eilat (http://www.iui-eilat.ac.il/Research/NMPMeteoData.aspx). During the five days of our experiment, surface water PAR reached 1200 µmoles photon m−2 s−1 at midday (Fig. S1). The PAR received at 10 m and 40 m depth peaked at ca. 550 µmoles photon m−2 s−1 and 50 µmoles photon m−2 s−1 respectively, considering attenuation coefficients of 0.072–0.1 m−1 at this precise location55,56. These values are in agreement with one-off measurements performed with a data logger during coral collection. The in situ seawater temperature (24 °C) and nutrient concentrations (<0.5 µM dissolved nitrogen, and <0.2 µM dissolved phosphorus) were stable throughout the investigated depth gradient and period of time (http://www.iui-eilat.ac.il/Research/NMPMeteoData.aspx). Coral nubbins were maintained for one day under these conditions before the following measurements were performed in the outside aquaria under exactly the same environmental conditions.

NaH13CO3 incubations

The rates at which carbon was fixed by the shallow and mesophotic coral colonies under their natural PAR levels were estimated using 13C- labelled bicarbonate according to Tremblay et al.4. To take into account variation in PAR levels during the day, corals were incubated for 5 h, between 10 am and 3 pm, to cover the maximal daily irradiance45 (Fig. S1). For each species and depth condition, 10 coral nubbins, from 10 different colonies were placed in individual beakers filled with 200 mL FSW enriched with 0.6 mM NaH13CO3 (98 atom % 13C, #372382, Sigma-Aldrich, St-Louis, MO, USA). After this “pulse” period of 5 h, half of the corals were sampled and stored frozen at −20 °C until further analysis (T0). The other half was transferred into 200 mL of non-enriched FSW for a chase period of 19 h (T24). The determination of %13C enrichment, and total carbon content in the symbionts and host compartments were performed with a Delta plus Mass spectrometer coupled to a C/N analyser (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The natural isotopic abundance of each species at each depth was determined from the corals used for the respiration measurements. Detailed calculations are described in Tremblay et al.4. Data were normalized to ash-free dry weight of the organisms27.

Physiological and tissue descriptor measurements

Estimation of the dark respiration rates of the whole colony, as well as of the isolated symbionts, was needed for the establishment of the daily carbon budget. Dark respiration rates were measured on four nubbins per species and depth (from four different colonies), as well as on freshly isolated symbionts from four other nubbins according to Tremblay et al.4. Dark-acclimated nubbins/symbionts were individually placed in stirred incubation chambers filled with 0.45 µM filtered seawater and maintained at 24 °C. Changes in dissolved oxygen were monitored over 30 minutes using optodes connected to an Oxy-4 (PreSense, Regensburg, Germany). Oxygen fluxes were converted into carbon equivalents (RC)4. The autotrophic carbon acquisition to respiration ratios (PC/RC) were estimated considering a maximal autotrophic carbon acquisition rate for 6 h, and a half rate for the remaining 6 h. At the end of the incubations, nubbins were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, freeze-dried, weighed for the total DW determination and processed as described in Pupier et al.27 (Supplementary information) for the further determination of the symbiont density, total chlorophyll concentration and ash-free dry weight (AFDW). The genus of the symbionts hosted by the shallow and mesophotic populations of Litophyton sp. and R. f. fulvum was investigated following the protocol of Santos et al.57.

Interspecies comparisons

To compare our data on soft corals, normalized to AFDW, with those found in the literature on scleractinian corals, often normalized to skeletal surface area, it was necessary to use the same normalization metric. As surface area could not be measured with accuracy on soft corals (since they have a highly variable hydroskeleton which expands and shrinks the colony size by several folds depending on the environmental conditions), we normalized all data to AFDW27. For this purpose, we chose eight nubbins (skeletal surface area ranging from 4 to 29 cm²) of the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata originating from the Red Sea and grown at the Monaco Scientific Center, as it is one of the dominant species in the Gulf of Eilat and many data have been acquired on this species. AFDW was determined as described above after separating the tissue from the skeleton and combusting it. Surface area was determined using the wax technique58. A conversion factor (255.65 ± 8.98, Table S4), estimated from the ratio between skeletal surface area (in cm²) and AFDW (in g) of these nubbins, was used to transform data normalized to surface area (Table S3) into data normalized to AFDW.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). All data were expressed as mean ± standard error. Prior to analyses, outlier values were identified using Grubb’s test and were excluded when p-values were significant (p < 0.05). Assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity of variance were evaluated through Shapiro’s and Bartlett’s tests along with graphical analyses of residuals. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to test the effect of species and depth on symbiont density, chlorophyll concentrations and carbon acquisition. The rates at which carbon was assimilated, translocated and lost were analysed separately between the two time points (i.e., pulse and chase periods) using 2-way ANOVAs with species and depth as fixed effects. When the interaction was significant pairwise, Tukey tests were performed as a posteriori testing.

References

Venn, A. A., Loram, J. E. & Douglas, A. E. Photosynthetic symbioses in animals. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 1069–1080 (2008).

Muscatine, L., Falkowski, P. G., Porter, J. W. & Dubinsky, Z. Fate of photosynthetic fixed carbon in light- and shade-adapted colonies of the symbiotic coral Stylophora pistillata. Proc. R. Soc. London 222, 181–202 (1984).

Falkowski, P. G., Dubinsky, Z., Muscatine, L. & Porter, J. W. Light and the bioenergetics of a symbiotic coral. Bioscience 34, 705–709 (1984).

Tremblay, P., Grover, R., Maguer, J.-F., Legendre, L. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Autotrophic carbon budget in coral tissue: a new 13C-based model of photosynthate translocation. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 1384–1393 (2012).

Ezzat, L., Fine, M., Maguer, J.-F., Grover, R. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Carbon and nitrogen acquisition in shallow and deep holobionts of the scleractinian coral S. pistillata. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 102 (2017).

Houlbrèque, F. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Heterotrophy in tropical scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev. 84, 1–17 (2009).

Schubert, N., Brown, D. & Rossi, S. Symbiotic versus non-symbiotic octocorals: physiological and ecological implications. In Marine Animal Forests: the Ecology of Benthic Biodiversity Hotspots 887–918 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17001-5 (2016).

Fabricius, K. E. & Dommisse, M. Depletion of suspended particulate matter over coastal reef communities dominated by zooxanthellate soft corals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 196, 157–167 (2000).

Fabricius, K. E. & De’ath, G. Photosynthetic symbionts and energy supply determine octocoral biodiversity in coral reefs. Ecol. Soc. Am. 89, 3163–3173 (2008).

Shoham, E. & Benayahu, Y. Higher species richness of octocorals in the upper mesophotic zone in Eilat (Gulf of Aqaba) compared to shallower reef zones. Coral Reefs 36, 71–81 (2017).

Stobart, B., Teleki, K., Buckley, R., Downing, N. & Callow, M. Coral recovery at Aldabra Atoll, Seychelles: five years after the 1998 bleaching event. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 363, 251–255 (2005).

Lenz, E. A., Bramanti, L., Lasker, H. R. & Edmunds, P. J. Long-term variation of octocoral populations in St. John, US Virgin Islands. Coral Reefs 34, 1099–1109 (2015).

Fabricius, K. E. & Klumpp, D. W. Widespread mixotrophy in reef-inhabiting soft corals: the influence of depth, and colony expansion and contraction on photosynthesis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 125, 195–204 (1995).

Ferrier-Pagès, C., Hoogenboom, M. O. & Houlbrèque, F. The role of plankton in coral trophodynamics. Coral Reefs An Ecosyst. Transit. 215–229 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0114-4 (2011).

Anthony, K. R. N., Hoogenboom, M. O., Maynard, J. A., Grottoli, A. G. & Middlebrook, R. Energetics approach to predicting mortality risk from environmental stress: a case study of coral bleaching. Funct. Ecol. 23, 539–550 (2009).

Ramsby, B. D., Shirur, K. P., Iglesias-Prieto, R. & Goulet, T. L. Symbiodinium photosynthesis in Caribbean octocorals. PLoS One 9, e106419 (2014).

Baker, D. M. et al. Productivity links morphology, symbiont specificity and bleaching in the evolution of Caribbean octocoral symbioses. ISME J. 9, 2620–2629 (2015).

Rossi, S. et al. Linking host morphology and symbiont performance in octocorals. Sci. Rep. 8, 12823 (2018).

Farrant, P. A., Borowitzka, M. A., Hinde, R. & King, R. J. Nutrition of the temperate Australian soft coral Capnella gaboensis I. Photosynthesis and carbon fixation. Mar. Biol. 95, 565–574 (1987).

Schlichter, D., Svoboda, A. & Kremer, B. P. Functional autotrophy of Heteroxenia fuscescens (Anthozoa: Alcyonaria): carbon assimilation and translocation of photosynthates from symbionts to host. Mar. Biol. 78, 29–38 (1983).

Sorokin, Y. Biomass, metabolic rates and feeding of some common reef zoantharians and octocorals. Mar. Freshw. Res. 42, 729–741 (1991).

Khalesi, M. K., Beeftink, H. H. & Wijffels, R. H. Energy budget for the cultured, zooxanthellate octocoral Sinularia flexibilis. Mar. Biotechnol. 13, 1092–1098 (2011).

Benayahu, Y. Faunistic composition and patterns in the distribution of soft corals (Octocorallia, Alcyonacea) along the coral reefs of Sinai peninsula. Proc 5th Int Coral Reef Congr 6 (1985).

Fabricius, K. E., Genin, A. & Benayahu, Y. Flow-dependent herbivory and growth in zooxanthellae-free soft corals. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40, 1290–1301 (1995).

Bednarz, V. N., Cardini, U., Van Hoytema, N., Al-Rshaidat, M. M. D. & Wild, C. Seasonal variation in dinitrogen fixation and oxygen fluxes associated with two dominant zooxanthellate soft corals from the northern Red Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 519, 141–152 (2015).

Haydon, T. D., Seymour, J. R. & Suggett, D. J. Soft corals are significant DMSP producers in tropical and temperate reefs. Mar. Biol. 165, 109 (2018).

Pupier, C. A., Bednarz, V. N. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Studies with soft corals - recommendations on sample processing and normalization metrics. Front. Mar. Sci. 5, 348 (2018).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 28, 2570–2580 (2018).

Hume, B. C. C. et al. Symbiodinium thermophilum sp. nov., a thermotolerant symbiotic alga prevalent in corals of the world’s hottest sea, the Persian/Arabian Gulf. Sci. Rep. 5, 8562 (2015).

Einbinder, S. et al. Novel adaptive photosynthetic characteristics of mesophotic symbiotic microalgae within the reef-building coral, Stylophora pistillata. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 195 (2016).

Lesser, M. P. et al. Photoacclimatization by the coral Montastraea cavernosa in the mesophotic zone: light, food, and genetics. Ecol. Soc. Am. 91, 990–1003 (2010).

Eyal, G. et al. Euphyllia paradivisa, a successful mesophotic coral in the northern Gulf of Eilat/Aqaba, Red Sea. Coral Reefs 35, 91–102 (2016).

Barneah, O., Weis, V. M., Perez, S. & Benayahu, Y. Diversity of dinoflagellate symbionts in Red Sea soft corals: mode of symbiont acquisition matters. Mar. Ecol. 275, 89–95 (2004).

LaJeunesse, T. C., Loh, W. & Trench, R. K. Do introduced endosymbiotic dinoflagellates ‘take’ to new hosts? Biol. Invasions 11, 995–1003 (2009).

Van Oppen, M. J. H., Mieog, J. C., Sánchez, C. A. & Fabricius, K. E. Diversity of algal endosymbionts (zooxanthellae) in octocorals: the roles of geography and host relationships. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2403–2417 (2005).

Goulet, T. L., Simmons, C. & Goulet, D. Worldwide biogeography of Symbiodinium in tropical octocorals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 355, 45–58 (2008).

Baker, A. C., McClanahan, T. R., Starger, C. J. & Boonstra, R. K. Long-term monitoring of algal symbiont communities in corals reveals stability is taxon dependent and driven by site-specific thermal regime. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 479, 85–97 (2013).

Goulet, T. L. & Coffroth, M. A. Stability of an octocoral-algal symbiosis over time and space. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 250, 117–124 (2003).

Mass, T. et al. Photoacclimation of Stylophora pistillata to light extremes: metabolism and calcification. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 334, 93–102 (2007).

Cohen, I. & Dubinsky, Z. Long term photoacclimation responses of the coral Stylophora pistillata to reciprocal deep to shallow transplantation: photosynthesis and calcification. Front. Mar. Sci. 2, 45 (2015).

Ziegler, M., Roder, C. M., Büchel, C. & Voolstra, C. R. Mesophotic coral depth acclimatization is a function of host-specific symbiont physiology. Front. Mar. Sci. 2, 4 (2015).

Cunning, R., Muller, E. B., Gates, R. D. & Nisbet, R. M. A dynamic bioenergetic model for coral-Symbiodinium symbioses and coral bleaching as an alternate stable state. J. Theor. Biol. 431, 49–62 (2017).

Scheuring, S. & Sturgis, J. N. Chromatic adaptation of photosynthetic membranes. Science. 309, 484–487 (2005).

Smith, E. G., D’Angelo, C. D., Sharon, Y., Tchernov, D. & Wiedenmann, J. Acclimatization of symbiotic corals to mesophotic light environments through wavelength transformation by fluorescent protein pigments. Proc. - R. Soc. London, Ser. B 284, 20170320 (2017).

Stambler, N. Light and picophytoplankton in the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba). J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 111, (2006).

Porter, J. W. Autotrophy, heterotrophy, and resource partitioning in Caribbean reef-building corals. Am. Nat. 110, 731–742 (1976).

Scheufen, T., Krämer, W. E., Iglesias-Prieto, R. & Enríquez, S. Seasonal variation modulates coral sensibility to heat-stress and explains annual changes in coral productivity. Sci. Rep. 7, 4937 (2017).

Leal, M. C. et al. Symbiont type influences trophic plasticity of a model cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 858–863 (2015).

Starzak, D. E., Quinnell, R. G., Nitschke, M. R. & Davy, S. K. The influence of symbiont type on photosynthetic carbon flux in a model cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Mar. Biol. 161, 711–724 (2014).

Baker, D. M., Freeman, C. J., Wong, J. C. Y., Fogel, M. L. & Knowlton, N. Climate change promotes parasitism in a coral symbiosis. ISME J. 12, 921 (2018).

Thornhill, D. J. et al. A connection between colony biomass and death in Caribbean reef-building corals. PLoS One 6, e29535 (2011).

Enríquez, S., Méndez, E. R., Hoegh-Guldberg, O. & Iglesias-Prieto, R. Key functional role of the optical properties of coral skeletons in coral ecology and evolution. Proc. - R. Soc. London, Ser. B 284, 20161667 (2017).

Wangpraseurt, D. et al. Lateral light transfer ensures efficient resource distribution in symbiont-bearing corals. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 489–498 (2014).

Bellworthy, J. & Fine, M. The Red Sea Simulator: A high-precision climate change mesocosm with automated monitoring for the long-term study of coral reef organisms. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 16, 367–375 (2018).

Akkaynak, D. et al. What is the space of attenuation coefficients in underwater computer vision? Proc. 30th IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, 568–577, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.68 (2017).

Tamir, R., Eyal, G., Kramer, N., Laverick, J. H. & Loya, Y. Light environment drives the shallow to mesophotic coral community transition. bioRxiv 622191 https://doi.org/10.1101/622191 (2019).

Santos, S. R. et al. Molecular phylogeny of symbiotic dinoflagellates inferred from partial chloroplast large subunit (23S)-rDNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 23, 97–111 (2002).

Veal, C. J., Carmi, M., Fine, M. & Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Increasing the accuracy of surface area estimation using single wax dipping of coral fragments. Coral Reefs 29, 893–897 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Allemand, Director of the Centre Scientifique de Monaco, for scientific support and the staff of the IUI for assistance on the field. This study was funded by the Centre Scientifique de Monaco and CFP was funded by “La Société des Explorations de Monaco”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.P., C.F.P., R.G. and V.B. conceived and designed the experiment. C.P. and C.R. performed data curation. C.P., C.F.P., M.F., R.G. and V.B. wrote the manuscript. C.F.P. and M.F. acquired funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pupier, C.A., Fine, M., Bednarz, V.N. et al. Productivity and carbon fluxes depend on species and symbiont density in soft coral symbioses. Sci Rep 9, 17819 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54209-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54209-8

This article is cited by

-

Lineage-specific symbionts mediate differential coral responses to thermal stress

Microbiome (2023)

-

Acclimatization of a coral-dinoflagellate mutualism at a CO2 vent

Communications Biology (2023)

-

Coupled carbon and nitrogen cycling regulates the cnidarian–algal symbiosis

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Harnessing solar power: photoautotrophy supplements the diet of a low-light dwelling sponge

The ISME Journal (2022)

-

Carbon budget trends in octocorals: a literature review with data reassessment and a conceptual framework to understand their resilience to environmental changes

Marine Biology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.