Abstract

The high metabolic activity associated with endurance flights and intense fuelling of migrant birds may produce large quantities of reactive oxygen species, which cause oxidative damage. Yet it remains unknown how long-lived birds prepare for oxidative challenges prior to extreme flights. We combined blood measurements of oxidative status and enzyme and fat metabolism in Hudsonian godwits (Limosa haemastica, a long-lived shorebird) before they embarked on non-stop flights longer than 10,000 km during their northbound migrations. We found that godwits increased total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and reduced oxidative damage (TBARS) as the pre-migratory season progressed, despite higher basal metabolic rates before departure. Elevations in plasma β-hydroxybutyrate and uric acid suggest that lipid and protein breakdown supports energetic requirements prior to migration. Significant associations between blood mitochondrial cytochrome-c oxidase and plasma TAC (negative) and TBARS (positive) during winter indicate that greater enzyme activity can result in greater oxidative damage and antioxidant responses. However enzyme activity remained unchanged between winter and premigratory stages, so birds may be unable to adjust metabolic enzyme activity in anticipation of future demands. These results indicate that godwits enhance their oxidative status during migratory preparation, which might represent an adaptation to diminish the physiological costs of long-distance migration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among the most extreme examples of physical performance in the animal kingdom are those of migratory birds, which make some of the most spectacular long-distance migrations of any organism on the planet1,2. In birds, the greatest endurance migrations are found among long-distance migratory shorebirds (Charadriiformes), with several members making annual journeys exceeding 30,000 km, including one or more non-stop trans-oceanic flights of 8000–12,000 km3. These powered flapping flights of up to 9 days duration, fuelled entirely from stored nutrients and sustained at very high metabolic rates, extend the limits of what is known of endurance physiology1.

Intense and prolonged physical activity is normally associated with an increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause oxidative damage to lipids, DNA and proteins4,5. While there is no one-to-one correspondence between ROS production and oxygen consumption, ROS production rates are expected to be substantially higher in animals with inherently high rates of oxygen consumption, particularly birds6,7. Therefore, oxidative stress (i.e. the accumulation of oxidative damage) might occur in migrating individuals as a result of increased ROS production linked to the high metabolic rates that accompany migration6,8. Unlike other vertebrates, birds rely primarily on fats (some of which are highly susceptible to attack by ROS) to fuel endurance migration, and thus face a greater potential for damage from the reactive by-products of their own metabolism8. Accordingly, some studies have shown that migrating birds can experience oxidative damage during long-duration flights9,10,11,12. For example, Jenni-Eiermann et al.11 found that European robins (Erithacus rubecula) experience oxidative damage during migratory flights and increase antioxidant capacity. Likewise, Skrip et al.12 found that fat stores positively correlated with circulating antioxidant capacity in blackpoll warblers (Setophaga striata) and red-eyed vireos (Vireo olivaceus) preparing for fall migration on Block Island, USA, but were uncorrelated in Italian garden warblers (Sylvia borin) after crossing the Sahara Desert and Mediterranean Sea. Together, these studies provide evidence that birds on stopover can prepare for, and recover from, oxidative challenges posed by migratory flights. However, most of the work has been done on passerine species which do not embark on extreme migration (i.e. non-stop flights >5000 km1). Furthermore, passerines are short-lived birds that usually compromise oxidative defences when faced with costly activities such as increased breeding effort13. The ‘oxidative stress theory of ageing’5 predicts that long-lived animals will have less cumulative oxidative damage together with structural characteristics that make them more resistant to oxidative damage itself. Indeed, a recent comparative study showed that bird species with longer lifespan have higher non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity and suffer less oxidative damage to their lipids14. Long-lived birds, such as shorebirds3, should thus exhibit higher oxidative defences in response to increased migration workload and thus ROS production.

Besides the oxidative cost caused by prolonged flights, migratory birds are also expected to experience oxidative damage during migratory fuelling15,16,17, as this typically involves increases in metabolism and caloric intake18. Long-distance migratory shorebirds accumulate large amounts of fat before take-off on migratory flights19,20. Given the importance of fats to migrant birds, circulating lipid metabolites are often used to assess individual energetic state. Overall, some lipid metabolites increase during fat deposition (triglycerides), whereas others increase during fat catabolism (glycerol and β-hydroxybutyrate)21,22,23; plasma uric acid can also increase due to the deamination of dietary protein for storage as fat or the catabolism of body protein during fasting21,22,23. Despite this, the metabolic correlates of long-distance travel in free-living migrants are as yet poorly studied in the context of oxidative stress12.

Here we integrated blood-based measurements of energy metabolism (lipid metabolites, mitochondrial enzyme activity) with oxidative status (oxidative damage and antioxidant capacity) and metabolic rate to examine how Hudsonian godwits (Limosa haemastica; hereafter “godwits”) prepare for oxidative challenges posed by extreme endurance migration. Individual godwits make non-stop flights of longer than 10,000 km during their northbound migrations from southern South America to Arctic and sub-Arctic Alaska and Canada24. Moreover, godwits can live up to 30 years or longer25 and thus provide an excellent model in which to study the link between oxidative stress and self-maintenance in a migratory context. We compared measurements of godwits sampled at three stages before embarking on their northbound migration. We hypothesized that godwits readying for departure would undergo preparation for oxidative challenges posed by extreme endurance migration. Specifically, we predicted (i) that fuelling and pre-departure individuals would increase their antioxidant capacity in anticipation of flight demands; (ii) that they would show strong correlations between lipid metabolites/fat scores and circulating non-enzymatic antioxidants; and (iii) that enzyme activity would correlate with metabolic rate and oxidative damage.

Methods

Study system and data collection

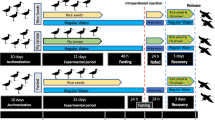

The study was carried out on a population of Hudsonian godwits (Fig. 1A) that spend the boreal winter on Chiloé Island, southern Chile26. Godwits depart from Chiloé Island in March and fly non-stop to central United States, with most individuals stopping only once before again flying non-stop to their breeding grounds in Alaska24. Individual godwits make non-stop flights of longer than 10,000 km and 7 days during their northbound migrations24 (Fig. 1B). Godwits were caught close to the high-tide roosts (incoming tides) using cannon nets from January to March 2018, spanning three pre-migration stages (based on body mass, fat scores and departure dates on Chiloé from 2014–2018; J.G. Navedo, unpublished data): ‘wintering’ (early January), ‘fuelling’ (mid-February), and ‘pre-departure’ (mid-March). Time elapsed from capture to high tide peak averaged 41 min (range 20–76 min). The potential effect of tide-enforced fasting on metabolite levels22 was probably small since godwits typically extend foraging activity up to 2.5 h after the low tide peak26 and their retention time (i.e. the average time for food to pass a bird’s digestive tract) is about 1.5 h27. Metabolite levels may also change during the time elapsed between capture and blood sampling. Birds were therefore blood-sampled as soon as possible after capture (mean 44 min, range 35–52 min). Approximately 1 ml blood was taken from the right jugular vein and stored within heparinized Eppendorf tubes maintained at 4 °C for up to 3 h. Next, tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm (relative centrifugal force = 9,250) for 10 min, plasma was separated from red blood cells and frozen at −80 °C until analysis. Samples were collected from 54 adults at wintering (n = 14:6 females and 8 males), fuelling (n = 19:11 females and 8 males), and pre-departure (n = 21:11 females and 10 males) stages. Time from capture to bleeding (hereafter “bleed time”) was used in analyses to determine whether there was an effect of time until bleeding on oxidative status and metabolite profiles. Upon capture, birds were also ringed, measured (body mass and standard morphometrics), aged (adult or juvenile), sexed (first based on relative bill length and later through molecular sexing), and had their fat depots scored28.

Scaled mass index

Godwits are sexually dimorphic in size and their mass is highly variable25. Thus, we calculated scaled mass index (SMI) for males and females separately following Peig & Green29. This method normalizes body mass to a fixed value of body size based on the scaling relationship between mass and length measures29. The fixed value of body size was the mean value of wing length for the study population: 220.8 ± 0.5 mm (n = 129) for females and 210.8 ± 0.4 mm (n = 208) for males (J.G. Navedo unpublished data).

Oxidative status

Lipid peroxidation in red blood cells was measured by the thiobarbituric acid test (thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances, TBARS), which relies on the ability of polyunsaturated fatty acids of cell membranes to readily react with ROS by donating a hydrogen atom30. Briefly, lipid peroxidation was measured using a commercial kit (Oxiselect, STA-330 Cell biolabs). The assay evaluates the joint between Malondialdehyde (MDA, a product of lipid peroxidation) and thiobarbituric acid. Absorbance was monitored in a Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO UV/VIS spectrophotometer at 25 °C. We determined hydrogen peroxides in plasma (H2O2, a major form of ROS) as a measure of the pro-oxidant status4 using a commercial kit (MAK311, Sigma Aldrich). The assay evaluated colorimetrically the oxidation of Fe+2 to Fe+3 by peroxides present in the sample at 585 nm.

We estimated non-enzymatic total antioxidant capacity (TAC) by measuring the capacity of a plasma sample to quench a standardized free radical challenge, following Sabat et al.31. Briefly, TAC was measured by colorimetric reaction using a commercial assay kit (Sigma Aldrich, San Diego, CA, #CS0790). The assay is based on the formation of a ferryl myoglobin radical from metmyoglobin and H2O2 which oxidizes the ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) to form the radical ABTS•+ which in turn produces a chromogen that can be detected spectrophotometrically at 405 nm (Multiskan GO). This protocol used the Trolox, a Vitamin E analog to be compared with the antioxidant capacity in a sample. As pointed out by Cohen et al.32 this method is a functional measure of antioxidant capacity that includes the action of micromolecular components such as vitamins E and C, and uric acid among others. Because uric acid has antioxidant properties and can reflect an adaptive response to oxidative stress33, we determined plasma uric acid concentrations (see below). Finally, we calculated oxidative balance as the ratio of TBARS and TAC (×1000) to generate a single variable (TBARS:TAC) that captured interindividual variation in oxidative balance (with higher values meaning higher oxidative stress9).

Mitochondrial enzyme activity

The enzyme activities of cytochrome c oxidase (COX, E.C. 1.9.3.1) and citrate synthase (CS, E.C. 4.1.3.7) were measured in mitochondrion of red blood cells as a proxy of metabolic intensity of other tissues, such as skeletal muscle34. COX is involved in the last reaction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain that is indicative of the energy capacity of the mitochondrial system, whereas CS catalyses the reduction of oxygen to water35. Besides, these metabolic enzymes in skeletal muscle are functionally associated with oxygen consumption (e.g., metabolic rate, see below) at the organismal level in birds31,35,36. COX and CS activities were measured using the methods described in Sabat et al.31,37. Enzyme activities are reported as specific activity per gram of protein (µmol min−1 mg protein−1). Protein concentration in plasma and red blood cell homogenate was determined after Bradford38 using bovine serum albumin as standard.

Plasma metabolites

We performed all metabolite assays at the Laboratorio Clínico Veterinario (Universidad Austral de Chile) using an auto-analyzer (Metrolab 2300, Wiener Lab). Briefly, total triglycerides (triglycerides plus free glycerol) was measured by enzymatic colorimetric assay (Triglycerides liquicolormono GPO-PAP kit, HUMAN GmbH) adapted to small sample volumes in 300 μL flat-bottom microplates. Glycerol concentration was determined by a coupled enzyme assay (Sigma-Aldrich MAK117). Concentration of uric acid was determined using the enzymatic colorimetric test with lipid clearing factor (uric acid liquicolor PAP kit, HUMAN GmbH). β-hydroxybutyrate was measured using colorimetric enzymatic reaction (D-3-hydroxybutyrate kit; Ranbut, Randox Laboratories). Triglyceride levels were calculated by subtracting free glycerol from total triglyceride levels23,39.

Metabolic rate measurements

A subsample of 18 adult birds was taken into nearby bird facilities at Quempillén Experimental Station for metabolic rate measurements. Due to logistical limitations we were not able to measure metabolic rates during the wintering period, so we measured the metabolic rates of fuelling (n = 10) and pre-departure (n = 8) godwits. Birds were housed in indoor aviaries (5 × 2.5 × 2.5 m) with access to freshwater and fasted for at least 6 h prior to metabolic trials the same night40. BMR was measured as the overnight oxygen consumption (\(\dot{V}\)O2, ml min−1) with a Field Metabolic System (FMS, Sable Systems, Las Vegas, NV). Birds (four individuals per night) were placed into adjacent metabolic chambers (15 L) in complete darkness and located in a temperature-controlled room at a constant temperature of 26 °C, i.e. within the thermoneutral zone40. Incurrent ambient air at a controlled flow rate of 10,000 mL min−1 was pumped through needle valves (air flow manifold MF-8; Sable Systems, Las Vegas, NV), which supplied five chambers with a constant flow (1400–2000 mL min−1). Excurrent air was subsampled at 200 mL min−1 and passed through a hygrometer, a CO2 analyser, and a fuel cell O2 analyser (i.e. the FMS). The O2 analyser was calibrated before each trial using 99.995% pure N2 as the low reference and ambient air scrubbed of water vapour and CO2 (set to 20.95% O2). The CO2 analyser was calibrated daily using pure N2 as the low reference and a certified mixture of 1.01% CO2 as the high reference. The hygrometer was calibrated weekly according to recommendations of the manufacturer. We used a multiplexer to monitor each chamber for 20 min before switching to the next chamber. A 10-min baseline of reference airflow, provided by an empty chamber of the same size, was measured after each round of recordings. All data were recorded using an analog-to-digital converter (UI-2; Sable Systems, Las Vegas, NV) connected to a laptop computer. We corrected for gas analyser drift and lag time of the respirometry system using ExpeData software. Main flow rate was corrected to standard temperature and pressure using eq. 8.6 in Lighton41. We did not scrub water vapour before gas analysis during measurements, but corrected for this dilution effect during data analysis using eq. 15.3 in Lighton41. \(\dot{V}\)O2 and CO2 production rate (\(\dot{V}\)CO2) were calculated using eqs. 11.7 and 11.8 in Lighton41, respectively. We considered BMR as the lowest 5-min average \(\dot{V}\)O2 over the test period. Finally, we calculated the respiratory quotient (RQ, i.e. the ratio of \(\dot{V}\)CO2 to \(\dot{V}\)O2). RQ varies from 0.7 (pure lipid catabolism) to 1.0 (pure carbohydrate catabolism); a mix of lipid and carbohydrate catabolism yields intermediate values41. BMR measured in the absence of CO2 absorbents gives a measure of the non–carbohydrate-fuelled metabolism of the animal, which can provide interesting data to demonstrate a shift in the catabolic allocation of respiratory substrates41. The body mass reported for BMR analysis was taken to be the mean of the initial measurement and the final measurement.

Statistical analyses

To test for temporal effects on physiological variables, we fitted separate general linear models (GLMs) with each trait measure in turn as the response variable. The full model included all three-way interactions between the fixed effects of pre-migration stage (wintering, fuelling, and pre-departure), sex, mass (either mass or SMI), and bleed time. For BMR analysis, GLM included stage (fuelling vs. pre-departure), sex, and mass. Model simplification was conducted using an information theoretical approach42. Because the weights of the ‘best’ models (lowest AIC) were always <0.9 (Appendix S1), we used model averaging to identify the most important predictor variables43. Relative importance analysis was carried out with the model-averaging approach42. In this way, we obtained model-averaged parameter estimates that were directly comparable to each other. We estimated the parameters from the set of all models for which the sum of Akaike weights reached >0.95. We considered predictor variables that had model-averaged 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that did not cross zero to be biologically relevant (i.e. significant). Results were qualitatively similar when using either body mass or SMI as predictor variable (Appendix S1). For simplicity, here we only present results from analyses using body mass. We ran all models using the R (version 3.5.1, R Core Team 2016) base function ‘glm’ and the MuMIn package for model averaging44.

To test for relationships between oxidative and metabolic variables, we ran regression analyses for the whole study period and for each stage separately. Predictor and response variables were log transformed when necessary to meet normality assumptions.

Ethics statement

All experimental procedures were carried out under the approval of the Bioethics Subcommittee of Universidad Austral de Chile (no 260/2016). All methods were carried out in accordance with these approved guidelines and regulations.

Results

Oxidative status

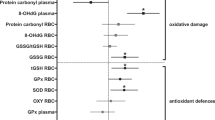

Levels of TBARS were lower at pre-departure (β = −2.88, s.e.m. = 1.110, CI = −5.11, −0.65), compared to wintering and fuelling stages (Fig. 2). Stage was the only important predictor for TBARS, having 71% relative importance. Likewise, H2O2 levels were lowest at pre-departure stage (β = −14.79, s.e.m. = 6.81, CI = −28.13, −1.46) (Fig. 2); stage had 73% relative importance. Conversely, TAC and uric acid concentrations were substantially higher at pre-departure stage (TAC: β = 1.48, s.e.m. = 0.44, CI = 0.60, 2.35; uric acid: β = 443.34, s.e.m. = 182.22, CI = 78.92, 807.76; Fig. 2), and stage was again the only important predictor variable for both TAC and uric acid, having 99% and 98% relative importance, respectively. Finally, TBARS:TAC was lowest at pre-departure (β = −1.62, s.e.m. = 0.49, CI = −2.61, −0.63; Fig. 2), indicating that levels oxidative stress were lowest at this stage. In this case stage was again the only clear significant predictor variable, having 96% relative importance.

Mitochondrial enzyme activity

There was no support for temporal (stage) and intrinsic (sex and body mass) effects on enzyme activity measures (all predictor variables had 95% CIs that crossed zero; Fig. 2 and Appendix S1). At the wintering stage, however, there were significant and positive associations between COX activity and oxidative damage (TBARS and H2O2), as well as a significantly negative association between COX activity and TAC (Fig. 3). In contrast, CS correlated negatively with TBARS and H2O2, and positively with TAC during the winter stage (Fig. 3). Neither COX nor CS activities were significantly correlated to oxidative status at the fuelling and pre-departure stages (always P > 0.05, Appendix S2).

Lipid metabolites and fat scores

Plasma β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations peaked during pre-departure (β = 0.48, s.e.m. = 0.19, CI = 0.10, 0.85; Fig. 4); stage was the only significant predictor variable for β-hydroxybutyrate, with a relative importance of 100%. In contrast, glycerol decreased with time, with concentration being lower at the fuelling (β = −0.057, s.e.m. = 0.02, CI = −0.10, −0.017) and pre-departure stages (β = −0.06, s.e.m. = 0.02, CI = −0.11, −0.02) (Fig. 4). None of the predictor variables had a strong effect on triglyceride concentrations (95% CIs crossed zero; Fig. 4). However, triglyceride concentrations correlated positively with fat scores (F1,45 = 4.42, P = 0.041). Fat scores were highest at pre-departure, particularly in males (GLM: stage(pre-departure): β = 3.83, s.e.m. = 0.58, CI = 2.69, 4.97; stage(pre-departure) × sex(male): β = 1.99, s.e.m. = 0.80, CI = 0.43, 3.55).

Metabolic rate measurements

BMR was higher in pre-departure godwits (β = 1.54, s.e.m. = 0.70, CI = 0.07, 3.00) than in fuelling godwits; stage had a relative importance of 65%. Overall body mass had a positive, significant effect on BMR (β = 0.03, s.e.m. = 0.01, CI = 0.002, 0.050, with a relative importance of 82%). Yet the interaction ‘body mass × sex’ (β = −0.05, s.e.m. = 0.02, CI = −0.09, −0.02) indicated that body mass had contrasting effects on BMR in the two sexes: BMR was positively correlated with body mass in females but the trend was negative in males. When using linear regression analysis between BMR and body mass, irrespective of sex and stage, values of BMR and body mass were significantly and positively correlated (F1,17 = 6.59, P = 0.021). Therefore, we used mass-independent BMR (residuals from its regression against body mass) to test for potential relationships between BMR and enzyme activities. Mass-independent BMR correlated positively with COX activity (F1,16 = 7.46, P = 0.015; Fig. 5), but not with CS activity (F1,11 = 0.81, P = 0.39). Neither whole-animal nor mass-independent BMR correlated with any markers of oxidative status (always P > 0.05). RQ did not differ between fuelling (0.74 ± 0.03) and pre-departure (0.76 ± 0.04) godwits (t1,17 = 1.34, P = 0.201), and did not correlate significantly with fat stores, lipid metabolites, and oxidative damage (always P > 0.05).

Discussion

We showed that Hudsonian godwits prepare for extreme non-stop flights on their ‘wintering’ grounds by simultaneously increase antioxidant capacity and reduce oxidative damage, despite the intense fuelling and high metabolic rates accompanying the pre-migration period. If considering the context of birds on stopover8, it is no surprise that godwits increase antioxidants as they build fat stores. Yet one might also expect them to experience oxidative damage during fuelling15,16. Instead, godwits decreased oxidative damage before take-off, which resulted in a more positive effect on their oxidative status. This likely represents an adaptation to diminish the oxidative costs during periods of flight and refuelling17. Moreover, these results support the notion that long-lived species are more resistant to oxidative damage than short‐lived ones14. Godwits are likely to prioritize self-maintenance, as shown by their increased antioxidant capacity, and this may underlie the pronounced longevity recorded in this and other long-distance migratory shorebirds3,25.

The positive trend in antioxidant capacity with time likely reflects the abundance of antioxidant-rich food resources on Chiloé. A recent study indicates that shorebird populations encounter a predictable and abundant food supply on the intertidal mudflats of Chiloé45. Hudsonian godwits mainly feed on polychaetes46,47, which could act as a source of antioxidants48. Importantly, dietary antioxidants can supplement or replace the action of endogenous components of the antioxidant system49. Thus, an increase in the intake of antioxidant-rich food during the pre-migratory period26 — irrespective of whether birds preferentially select food rich in antioxidants or antioxidant resources come from a variety of food items available in their natural habitat — is likely to have reduced oxidative damage in pre-departure godwits. As pointed out by Beaulieu & Schaefer50, migratory birds may use specific antioxidants in anticipation of impending need. This strategy could be important for godwits as they may be unable to ameliorate any damage during non-stop flights. Furthermore, the risk of excessive flight muscle catabolism increases with the duration of non-stop flights11, a situation regularly faced by godwits en route19,20. Thus, godwits must heavily invest in antioxidant defences against the consequences of flight muscle catabolism and resulting oxidative damage.

Additionally, plasma concentrations of three key metabolites varied among stages. The elevation in plasma β-hydroxybutyrate (a ketone body synthesized from free fatty acids) prior to endurance flight may replace part of the glucose during short-term fasting22,51. Previous work with Bar-tailed godwits (Limosa lapponica) subjected to inactive fasting during stopover showed a trend to increase plasma butyrate22, suggesting that it supports general energetic requirements rather than the specific energetic demands of flight. It is therefore possible that godwits subjected to short-term, tide-enforced fasting increased plasma β-hydroxybutyrate temporarily. However, the time elapsed from capture and high tide peak (roosting) was similar across stages, and thus unlikely to have caused seasonal differences in levels of β-hydroxybutyrate and other metabolites. An alternative explanation is that godwits readying for departure had started mobilizing lipids. This is likely as pre-departure godwits had reached peak fat scores and the numbers of godwits on Chiloé dropped in mid-March (when they were captured). Elevated levels of β-hydroxybutyrate reduce glucose utilization and play an important role in the sparing of carbohydrate and protein52. Consequently, the plasma β-hydroxybutyrate levels of pre-departure godwits were increased compared with wintering and fuelling godwits. This is also consistent with the finding that elevated β-hydroxybutyrate in semipalmated sandpipers (Calidris pusilla) at stopover areas reflects slower weight gain prior to non-stop flight to the breeding grounds23. In contrast, glycerol concentrations were lower in birds preparing for migration, compared to those of overwintering ones. Glycerol is produced by lipolysis of triglycerides in adipose tissue and muscle during periods of negative energy balance and exercise53. Fuelling and pre-departure godwits were likely in positive energy balance, albeit the higher metabolic rates before flight. Thus, glycerol levels may have decreased due to high rates of fat deposition. This is consistent with a study with captive western sandpipers (Calidris mauri) showing that plasma glycerol was negatively related to mass gain54.

The significant increase in uric acid levels at the pre-departure stage likely indicates that birds increased their intake of dietary protein prior to endurance flight, given that uric acid is the final product of protein catabolism in birds and correlates closely with protein consumption55. Nonetheless, higher uric acid concentrations in pre-departure godwits could have also resulted from the breakdown of proteins that originate from body tissue. This seems to be the case for other birds that change body composition while preparing for a migratory flight20,56,57, suggesting a common pattern in allocation of lean body mass prior to endurance flight. Notably, bar-tailed godwits preparing to depart exhibit a reduction in size of digestive tissues, possibly to fly with a total mass as low as possible19,20. Overall, changes in plasma β-hydroxybutyrate and uric acid concentrations suggest that during the premigratory period energy expenditure entails catabolism of lipids and proteins rather than a shift in fuel substrate. Indeed, the similar RQ in fuelling and pre-departure individuals indicates that they used predominantly, but not solely, fat as fuel. Unfortunately we did not measured BMR in overwintering birds, so we do not know whether they increased their BMR throughout the entire pre-migratory period. However, pre-departure godwits had higher BMR than fuelling godwits, probably reflecting changes in the size or metabolic activity of different organs and tissues associated with migratory disposition18,58. Interestingly BMR increased with mass in females, but not in males. Sexual dimorphism in BMR has been reported for several bird species59,60. Such sex differences in the relationships between BMR and body mass may result from between-sex differences in metabolically inactive tissues such as fat (males had larger fat scores than females at pre-departure) and/or differences in the amount of energy required for energetically demanding tasks, such as migration and reproduction18,59.

Although the relationship between the rate of oxygen consumption and the generation of ROS is currently unresolved61,62,63, some studies have found support for a functional relationship between mass-specific metabolic rates and oxidative status31,64. For example, Sabat et al.31 showed that increased salt intake elicited changes in the BMR of Rufous-collared sparrows (Zonotrichia capensis), which were in turn coupled with an increase in the activity of mitochondrial enzymes and changes in oxidative status. Although we did not find a significant relationship between mass-independent BMR and oxidative status, we found that mass-independent BMR correlated positively with COX activity in mitochondria from red blood cells, suggesting that the rate of oxygen consumption is to some extent driven by tissue-specific metabolic demands. This supports the notion that avian erythrocytes possess functional mitochondria in terms of respiratory activities and ROS production65,66. Moreover, mitochondrial parameters (such as mitochondrial O2 consumption, the capacity of the electron transport system and the capacity to produce ATP via oxidative phosphorylation) measured in red blood cells correlated to those measured in the pectoral muscle in free-ranging king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonica)34. Hence, measures of mitochondrial function in red blood cells may reflect what is happening in other tissues (e.g., pectoral muscle), and thus provide general information at the organismal level34. This warrants further investigation since blood enzyme activities could represent informative non-invasive markers for monitoring the rate of energy expenditure in free-ranging birds, only requiring a small volume (~30 μl) of blood. In addition, we found that TBARS increased, yet TAC decreased, with COX activity during the wintering period. This finding indicates that greater enzyme activity can result in greater oxidative damage outside the migration period. Conversely, we found the opposite pattern for CS. The reason of this contradictory result is puzzling. A recent study67 found CS activity in blood cells of chicks of yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis) was negatively correlated with mtDNA damage, indicating a negative relationship between oxidative damage and mitochondrial activity. Nevertheless, biochemical variables and oxidative damage in gull chicks were also correlated with growth rate. Thus, we cannot rule out that the negative association between CS and oxidative damage found in overwintering godwits was caused by other physiological processes (such as tissue growth and repair) occurring in parallel. It is important to note that blood enzyme activities did not increased prior to endurance flight. Along this line, adult western sandpipers ready to migrate did not alter flight muscle catabolic enzymes (including CS activity) from earlier in the winter, suggesting that modulation of several physiological characteristics occur after migratory movements began68. Likewise, the levels of CS in semipalmated sandpipers preparing to migrate non-stop from eastern Canada to wintering sites on the northwest coast of South America in late summer do not change before their transoceanic flight, suggesting that changes in body composition can occur without an increase in mitochondrial enzymes69. Together, these findings imply that before spring migration, different shorebirds may be unable to adjust their metabolic enzyme activity in anticipation of future demands68.

Our findings provide an exciting opportunity for future work to test the hypothesis that high levels of ROS will drive potential long-term costs of oxidative stress in animals responding the challenges of a demanding migration, which must be scheduled optimally around other activities such as reproduction, moult, and territory acquisition3. To better understand the oxidative costs and defences, one important challenge in the future will be to determine how oxidative status may affect timing of migration and thus reproduction. Further studies should also examine how this physiological parameter is balanced between parents and offspring70. In this context, a longitudinal approach examining the oxidative status of organisms throughout the different stages of their annual cycle will be valuable. In the face of rapid and extensive human-induced environmental change, understanding how migratory animals accrue adequate energy stores and regulate the levels of pro-oxidants and antioxidants have far-reaching implications for evolutionary and population ecology, as well as for animal conservation and related policy decisions.

In conclusion, our study shows that trans-hemispheric migrant birds can increase circulating antioxidant capacity and reduce oxidative damage in anticipation of extreme non-stop flights. Our results indicate that godwits do not experience greater levels of oxidative stress during intense fuelling. They also suggest that alleviation of the accumulation of oxidative damage seems to start early in the pre-migration season, which may be a selective advantage for individuals that have higher rates of aerobic respiration. While extreme non-stop migration can represent an oxidative challenge for animals, protective mechanisms like increasing antioxidant defences and decreasing oxidative damage seem to occur in Hudsonian godwits. This might represent an adaptation to diminish the physiological costs of endurance migration.

References

Hedenström, A. Extreme endurance migration: what is the limit to non-stop flight? PLoS Biol. 8, e1000362 (2010).

Piersma, T. Why marathon migrants get away with high metabolic ceilings: towards an ecology of physiological restraint. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 295–302 (2011).

Conklin, J. R., Senner, N. R., Battley, P. F. & Piersma, T. Extreme migration and the individual quality spectrum. J. Avian Biol. 48, 19–36 (2017).

Costantini, D. Oxidative stress and hormesis in evolutionary ecology and physiology. Oxidative Stress and Hormesis in Evolutionary Ecology and Physiology, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-54663-1 (2014).

Finkel, T. & Holbrook, N. J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408, 239–247 (2000).

Costantini, D. Oxidative stress in ecology and evolution: Lessons from avian studies. Ecol. Lett. 11, 1238–1251 (2008).

Buttemer, W. A., Abele, D. & Costantini, D. From bivalves to birds: Oxidative stress and longevity. Funct. Ecol. 24, 971–983 (2010).

Skrip, M. M. & McWilliams, S. R. Oxidative balance in birds: An atoms-to-organisms-to-ecology primer for ornithologists. J. F. Ornithol. 87, 1–20 (2016).

Costantini, D., Cardinale, M. & Carere, C. Oxidative damage and anti-oxidant capacity in two migratory bird species at a stop-over site. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 144, 363–371 (2007).

Eikenaar, C., Hegemann, A., Packmor, F., Kleudgen, I. & Isaksson, C. Not just fuel: energy stores are correlated with immune function and oxidative damage in a long-distance migrant. Curr. Zool., https://doi.org/10.1093/cz/zoz021 (2019).

Jenni-Eiermann, S., Jenni, L., Smith, S. & Costantini, D. Oxidative stress in endurance flight: An unconsidered factor in bird migration. PLoS One 9, 1–6 (2014).

Skrip, M. M. et al. Migrating songbirds on stopover prepare for, and recover from, oxidative challenges posed by long-distance flight. Ecol. Evol. 5, 3198–3209 (2015).

Alonso-Alvarez, C. et al. Increased susceptibility to oxidative stress as a proximate cost of reproduction. Ecol. Lett. 7, 363–368 (2004).

Vagasi, C. et al. Longevity and life history coevolve with oxidative stress in birds. Funct. Ecol. 33, 152–161 (2019).

Costantini, D., Metcalfe, N. B. & Monaghan, P. Ecological processes in a hormetic framework. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1435–1447 (2010).

Eikenaar, C., Jönsson, J., Fritzsch, A., Wang, H. L. & Isaksson, C. Migratory refueling affects non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity, but does not increase lipid peroxidation. Physiol. Behav. 158, 26–32 (2016).

Eikenaar, C., Källstig, E., Andersson, M. N., Herrera-Dueñas, A. & Isaksson, C. Oxidative challenges of avian migration: A comparative field study on a partial migrant. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 90, 223–229 (2017).

Swanson, D. L. Seasonal metabolic variation in birds: functional and mechanistic correlates. Curr. Ornithol. 17, 75–129 (2010).

Piersma, T. & Gill, R. E. Guts Don’t Fly: Small Digestive Organs in Obese Bar-Tailed Godwits. Auk 115, 196–203 (1998).

Landys-Ciannelli, M. M., Piersma, T. & Jukema, J. Strategic size changes of internal organs and muscle tissue in the Bar-tailed Godwit during fat storage on a spring stopover site. Funct. Ecol. 17, 151–159 (2003).

Jenni-Eiermann, S., Jenni, L. & Piersma, T. Plasma metabolites reflect seasonally changing metabolic processes in a long-distance migrant shorebird (Calidris canutus). Zoology 105, 239–246 (2002).

Landys, M. M. et al. Metabolic profile of long-distance migratory flight and stopover in a shorebird. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 295–302, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.2952 (2005).

Lyons, J. E., Collazo, J. A. & Guglielmo, C. G. Plasma metabolites and migration physiology of semipalmated sandpipers: refueling performance at five latitudes. Oecologia 155, 417–27 (2008).

Senner, N. R., Hochachka, W. M., Fox, J. W. & Afanasyev, V. An exception to the rule: Carry-over effects do not accumulate in a long-distance migratory bird. PLoS One 9 (2014).

Walker, B. M., Senner, N. R., Elphick, C. S. & Klima, J. Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica). In The Birds of North America Online (ed. Poole, A.) (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2011).

Navedo, J. G. et al. Assessing the effects of human activities on the foraging opportunities of migratory shorebirds in Austral high-latitude bays. PLoS One 14, 1–16 (2019).

Navedo, J. G. et al. Unravelling trophic subsidies of agroecosystems for biodiversity conservation: Food consumption and nutrient recycling by waterbirds in Mediterranean rice fields. Sci. Total Environ. 511, 288–297 (2015).

Meissner, W. A classification scheme for scoring subcutaneous fat depots of shorebirds. J. F. Ornithol. 80, 289–296 (2009).

Peig, J. & Green, A. J. New perspectives for estimating body condition from mass/length data: The scaled mass index as an alternative method. Oikos 118, 1883–1891 (2009).

Isaksson, C., Sturve, J., Almroth, B. C. & Andersson, S. The impact of urban environment on oxidative damage (TBARS) and antioxidant systems in lungs and liver of great tits, Parus major. Environ. Res. 109, 46–50 (2009).

Sabat, P. et al. Coping with salt water habitats: Metabolic and oxidative responses to salt intake in the rufous-collared sparrow. Front. Physiol. 8 (2017).

Cohen, A., Klasing, K. & Ricklefs, R. Measuring circulating antioxidants in wild birds. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 147, 110–121 (2007).

Costantini, D. On the measurement of circulating antioxidant capacity and the nightmare of uric acid. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2, 321–325 (2011).

Stier, A. et al. How to measure mitochondrial function in birds using red blood cells: A case study in the king penguin and perspectives in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 1172–1182 (2017).

Peña-Villalobos, I., Nuñez-Villegas, M., Bozinovic, F. & Sabat, P. Metabolic enzymes in seasonally acclimatized and cold acclimated rufous-collared sparrow inhabiting a Chilean Mediterranean environment. Curr. Zool. 60, 338–350 (2014).

Swanson, D., Zhang, Y. & King, M. Mechanistic drivers of flexibility in summit metabolic rates of small birds. PLoS One 9 (2014).

Sabat, P. et al. The interplay between ambient temperature and salt intake affects oxidative status and immune responses in a ubiquitous Neotropical passerine, the rufous-collared sparrow. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. -Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 234, 50–59 (2019).

Bradford, M. A rapid and sensitive assay of protein utilizing the principle of bye dying. Anal. Biochem. 28–264 (1976).

Jenni-Eiermann, S. & Jenni, L. Plasma metabolite levels predict individual body-mass changes in a small long-distance migrant, the Garden warbler. Auk 111, 888–899 (1994).

Gutiérrez, J. S., Abad-Gómez, J. M., Sánchez-Guzmán, J. M., Navedo, J. G. & Masero, J. A. Avian BMR in marine and non-marine habitats: A test using shorebirds. PLoS One 7 (2012).

Lighton, J. R. B. Measuring metabolic rates: a manual for scientists. Measuring metabolic ates: a manual for scientists, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195310610.001.0001 (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model selection and multi-model inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. (2nd ed. Springer, 2002).

Grueber, C. E., Nakagawa, S., Laws, R. J. & Jamieson, I. G. Multimodel inference in ecology and evolution: Challenges and solutions. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 699–711 (2011).

Barton, K. MuMIn: multi-model inference. R package version 1.42.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn (2018).

Micael, J. & Navedo, J. G. Macrobenthic communities at high southern latitudes: Food supply for long-distance migratory shorebirds. Austral Ecol. 43, 955–964 (2018).

Martínez-Curci, N. S., Azpiroz, A. B., Isacch, J. P. & Elías, R. Dietary relationships among Nearctic and Neotropical migratory shorebirds in a key coastal wetland of South America. Emu 115, 326–334 (2015).

Senner, N. R. & Coddington, K. S. C. Habitat use and foraging ecology of Hudsonian Godwits Limosa haemastica in southern South America. Wader Study Gr. Bull. 118, 105–108 (2011).

Moraes, T. B. et al. Antioxidant properties of the mucus secreted by Laeonereis acuta (Polychaeta, Nereididae): A defense against environmental pro-oxidants? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 142, 293–300 (2006).

Pamplona, R. & Costantini, D. Molecular and structural antioxidant defenses against oxidative stress in animals. Am. J. Physiol. - Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 301, R843–R863 (2011).

Beaulieu, M. & Schaefer, H. M. Rethinking the role of dietary antioxidants through the lens of self-medication. Anim. Behav. 86, 17–24 (2013).

Jenni-Eiermann, S. & Jenni, L. Metabolic differences between the postbreeding, moulting and migratory periods in feeding and fasting passerine birds. Funct. Ecol. 10, 62–72 (1996).

Robinson, A. M. & Williamson, D. H. Physiological roles of ketone bodies as substrates and signals in mammalian tissues. Physiol. Rev. 60, 143–87 (1980).

Stevens, L. Avian Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Avian Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511525773 (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Williams, T. D., Guglielmo, C. G. & Martyniuk, C. J. Plasma lipid metabolites provide information on mass change over several days in captive Western sandpipers. Auk 116, 994–1000 (1999).

Alan, R. R. & McWilliams, S. R. Oxidative stress, circulating antioxidants, and dietary preferences in songbirds. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 164, 185–193 (2013).

Jehl, J. R. Cyclical Changes in Body Composition in the Annual Cycle and Migration of the Eared Grebe Podiceps nigricollis. J. Avian Biol., https://doi.org/10.2307/3677306 (2007).

Piersma, T., Gudmundsson, G. A. & Lilliendahl, K. Rapid changes in the size of different functional organ and muscle groups during refueling in a long-distance migrating shorebird. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 72, 405–15 (1999).

Kvist, A. & Lindstrom, A. Basal metabolic rate in migratory waders: intra-individual, intraspecific, interspecific and seasonal variation. Funct. Ecol. 15, 465–473 (2001).

Mathot, K. J., Martin, K., Kempenaers, B. & Forstmeier, W. Basal metabolic rate can evolve independently of morphological and behavioural traits. Heredity (Edinb). 111, 175–181 (2013).

Maloney, S. K. & Dawson, T. J. Sexual dimorphism in basal metabolism and body temperature of a large bird, the Emu. Condor 95, 1034–1037 (1993).

Speakman, J. R. & Garratt, M. Oxidative stress as a cost of reproduction: Beyond the simplistic trade-off model. BioEssays 36, 93–106 (2014).

Jimenez, A. G. “The same thing that makes you live can kill you in the end”: Exploring the effects of growth rates and longevity on cellular metabolic rates and oxidative stress in mammals and birds. Integr. Comp. Biol. 58, 544–558 (2018).

Salin, K. et al. Individuals with higher metabolic rates have lower levels of reactive oxygen species in vivo. Biol. Lett. 4–7, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0538 (2015).

Fletcher, Q. E. et al. Oxidative damage increases with reproductive energy expenditure and is reduced by food-supplementation. Evolution 67, 1527–1536 (2013).

Stier, A. et al. Avian erythrocytes have functional mitochondria, opening novel perspectives for birds as animal models in the study of ageing. Front. Zool. 10, 33 (2013).

Nikinmaa, M. Vertebrate Red Blood Cells: Adaptations of Function to Respiratory Requirements. (Springer-Verlag, 1990).

Velando, A., Noguera, J. C., da Silva, A. & Kim, S. Y. Redox-regulation and life-history trade-offs: scavenging mitochondrial ROS improves growth in a wild bird. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–9 (2019).

Guglielmo, C. G., Haunerland, N. H., Hochachka, P. W. & Williams, T. D. Seasonal dynamics of flight muscle fatty acid binding protein and catabolic enzymes in a migratory shorebird. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 282, R1405–R1413 (2002).

Driedzic, R., Crowe, A. N. D. H. L., Hicklin, W. & Sephton, H. Adaptations in pectoralis muscle, heart mass, and energy metabolism during premigratory fattening in semipalmated sandpipers (Calidris pusilla). Can. J. Zool. 71, 1608 (1993).

Blount, J. D., Vitikainen, E. I. K., Stott, I. & Cant, M. A. Oxidative shielding and the cost of reproduction. Biol. Rev. 91, 483–497 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Bird Ecology Lab for assistance in the field and in the lab and member of CECPAN for essential logistic support. J.S.G. would like to thank Lucy Hawkes, Phil Battley and Jon Blount for helpful discussions on the oxidative challenges of migration. José A. Masero, Andrea Soriano-Redondo and two anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This study was supported by the Universidad Austral de Chile (Grant No. SE-2018-01 to J.S.G.), and FONDECYT grants to J.G.N. (No. 1161224) and P.S. (No. 1160115). J.S.G. was supported by the Government of Extremadura while writing (Grant No. TA18001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.G. and J.G.N. designed the research and collected the samples. J.S.G. and L.E.C. measured metabolic rates. P.S. designed biochemical analyses. C.C., L.N. and I.P.-V. performed lab analyses. J.S.G. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with contributions and revisions by all authors. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutiérrez, J.S., Sabat, P., Castañeda, L.E. et al. Oxidative status and metabolic profile in a long-lived bird preparing for extreme endurance migration. Sci Rep 9, 17616 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54057-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54057-6

This article is cited by

-

The oxidative balance and stopover departure decisions in a medium- and a long-distance migrant

Movement Ecology (2023)

-

Effect of urbanization on individual condition of a threatened seabird: the Olrog’s Gull Larus atlanticus

Urban Ecosystems (2023)

-

Intra-urban variation in body condition, body size and oxidative status of Rufous-collared sparrow relate to urban green space attributes in a Latin American metropolis

Urban Ecosystems (2023)

-

Wild common crossbills produce redder body feathers when their wings are clipped

BMC Zoology (2022)

-

Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation response overrides glucocorticoid-induced stress in a reptile

Journal of Comparative Physiology B (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.