Abstract

Phosphorus (P) is the second most important macronutrient that limits the plant growth, development and productivity. Inorganic P fertilization in podzol soils predominantly bound with aluminum and iron, thereby reducing its availability to crop plants. Dairy manure (DM) amendment to agricultural soils can improve physiochemical properties, nutrient cycling through enhanced enzyme and soil microbial activities leading to improved P bioavailability to crops. We hypothesized that DM amendment in podzol soil will improve biochemical attributes and microbial community and abundance in silage corn cropping system under boreal climate. We evaluated the effects of organic and inorganic P amendments on soil biochemical attributes and abundance in podzol soil under boreal climate. Additionally, biochemical attributes and microbial population and abundance under short-term silage corn monocropping system was also investigated. Experimental treatments were [P0 (control); P1: DM with high P2O5; P2: DM with low P2O5; P3: inorganic P and five silage-corn genotypes (Fusion RR, Yukon R, A4177G3RIB, DKC 23-17RIB and DKC 26-28RIB) were laid out in a randomized complete block design in factorial settings with three replications. Results showed that P1 treatment increased acid phosphatase (AP-ase) activity (29% and 44%), and soil available P (SAP) (60% and 39%) compared to control treatment, during 2016 and 2017, respectively. Additionally, P1 treatments significantly increased total bacterial phospholipids fatty acids (ΣB-PLFA), total phospholipids fatty acids (ΣPLFA), fungi, and eukaryotes compared to control and inorganic P. Yukon R and DKC 26-28RIB genotypes exhibited higher total bacterial PLFA, fungi, and total PLFA in their rhizospheres compared to the other genotypes. Redundancy analyses showed promising association between P1 and P2 amendment, biochemical attributes and active microbial population and Yukon R and DKC 26-28RIB genotypes. Pearson correlation also demonstrated significant and positive correlation between AP-ase, SAP and gram negative bacteria (G−), fungi, ΣB-PLFA, and total PLFA. Study results demonstrated that P1 treatment enhanced biochemical attributes, active microbial community composition and abundance and forage production of silage corn. Results further demonstrated higher active microbial population and abundance in rhizosphere of Yukon R and DKC 26-28RIB genotypes. Therefore, we argue that dairy manure amendment with high P2O5 in podzol soils could be a sustainable nutrient source to enhance soil quality, health and forage production of silage corn. Yukon R and DKC 26-28RIB genotypes showed superior agronomic performance, therefore, could be good fit under boreal climatic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fertilizers are crucial inputs affecting the soil fertility, health and quality to optimize agricultural production. However, the minimal inputs of organic nutrient sources and dependency on inorganic fertilizers generally reduce soil organic carbon (SOC) and total microbial biomass (TMB) resulting in reduced soil health and overall crop productivity1. Therefore, to uplift the soil health and physiochemical properties, management practices such as manure application, crop residue incorporation2,3,4. Sustainable cropping systems involves the integrated use of organic (manure or crop residues) and inorganic fertilizer inputs to improve the ecosystem functioning and microbial activities in nutrients provisioning to growing plants5. For example, dairy manure (DM) and inorganic fertilizer used as organic and inorganic soil amendments can restore SOC and soil health6,7. Organic amendments substantially improve the soil C retention resulting in higher crop harvests8, retain C in the surface soil, and increase crop yields9. Furthermore, soil organic amendments could reduce the dependency on inorganic fertilizers10. Thus, amending soil with appropriate organic mineral source could be a better strategy to improve soil C and soil health through active microbial community structure under low fertility as well as in shallow soils4,11. DM and other organic mineral sources provide the essential plant nutrients through improved soil aggregations and aeration, adding organic matter (OM) and maintain soil pH particularly in acidic soils12,13,14.

Phosphorus (P) is the second important macronutrient limiting the plant growth and is least mobile nutrient plant rhizosphere15. Despite P being quite abundant in many soils, it is largely unavailable for plant uptake because P forms insoluble complexes with cations under acid and alkaline conditions. As a result, a large amount of inorganic P fertilizers has been applied to sustain agricultural production systems. Currently, global P fertilization is approximately 50 million tons with a projected annual increase of 20 million tons by 2030. It is also important to note the import of inorganic P fertilizers in areas such as Newfoundland where all inorganic P comes from mainland with significant dollar amount. Excessive P fertilization contributes to greenhouse gases and has a direct negative impact on surface waters that influence the functioning of ecosystems. This creates a challenge for the goal of increasing crop production while using inputs in such a way as to avoid environmental problems. Excessive or little P application led to severe and negative impacts on environment by causing by land degradation under P deficient conditions and eutrophication under excessive application16. The global crop productivity has strong relationship with soil fertility and most of the world soils are P deficient hence leading to lower crop productivity, however P deficiency is more often found in old weathered soils. Podzolic soils typically have a coarse-sandy texture and high acidity, with pH in the topsoil layer around 4 to 4.517. These conditions signal a poor nutrient supply for agricultural crops. However, climatic changes might cause a northward shift of warmer weathers to provide enough crop heat units to exploit the agricultural resources, such as marginal lands in the boreal ecosystem characterized with podzol soils18,19. Such expansions of agricultural farmlands in the boreal ecosystem is one of the prime objectives to enhance the food production and food security; however, the marginal shallow agricultural lands with acidic soils are considered main limiting factor in production20,21. Hence, there is a need to investigate the effects of agricultural practices on soil health, quality and crop production for sustainable agriculture in the podzolic soils of the boreal ecosystem. Owing to P role in cell division as a component of nucleoproteins, it is involved in the cell reproduction, vegetative as well as reproductive development22. DM application increased soil acid phosphatase (AP-ase) and soil available phosphorus (SAP)23,24, and AP-ase is directly related to soil microbial activities25, and play major role in organic matter (OM) degradation, mineralization processes and plant nutrients availability26. TMB influences the physiochemical and biochemical soil properties; for instance, nutrient cycling and micro aggregation, thereby altering the soil biochemical environment and enhancing the crop production1,27,28. Hence, the presence of microbes and their richness is considered as a key tenet of soil quality in agricultural production systems. Different fertilization regimes affect soil microbial community (SMC) composition and structure, as bacteria is predominantly adapted to high available C and rich nutrient conditions whereas; fungi seem to be more adapted to recalcitrant C sources29. Different fertilization regimes affect SMC composition and structure, as bacteria is predominantly adapted to high available C and rich nutrient conditions, whereas, fungi seem to be more adapted in recalcitrant C sources30,31. Furthermore, chemical fertilizers applications may have potential effects on TMB and activities32. Very little is currently known concerning how DM and inorganic fertilizer amendment as P source affect soil biochemistry (enzymes, SAP, pH) and active microbial community composition in podzols used for agriculture production in boreal climates33.

Crop rotations could result in enhanced soil health in long-term agricultural production systems through regulating microbial community structures17. Such effects originated by selective root exudations by growing crop to build-up active microbes in rhizosphere34,35,36. There is substantial body of knowledge on effects of long-term mono-cropping, intercropping, crop rotation and cropping sequence on microbial community composition and abundance. However, there is a scarcity of information on the effects of short-term cultivations of silage corn on soil biochemical properties and the active microbial community composition and diversity in podzols under cool climates in boreal ecosystem37. Podzolic soils are coarse and sandy in texture with low pH38. Generally, the podzols are found in boreal ecosystem and temperate regions representing about 4% of total land surface area39. Podzolic soils are characterized humified OM in illuviated B horizons along with aluminum and iron, often seen as light colored Ae horizon38. Such conditions signal a poor nutrient supply and soil health for agricultural production systems. However, changing demands for agricultural land use due to climate-change and its northward shift necessitate the conversion of podzolic soils for agriculture production to meet the food security challenges in the 21st century21. Considering podzols are not traditionally used for agriculture, there is limited knowledge related to how different management practices and genotypes affect the active soil microbial population and biochemical properties.

We hypothesized that organic and inorganic P amendments would change the soil biochemical attributes and health by modulating the active microbial composition and abundance and nutrient availability of silage-corn cultivated in boreal ecosystem. To test the hypothesis, a field experiment was conducted: (i) to investigate the effects of DM and inorganic P (IP) amendments on biochemical attributes and active microbial community composition and abundance (ii) to determine the response of silage corn genotypes cultivated as short term monocrop on the soil biochemical properties and the active microbial community composition and abundance amended with different P amendments.

Results

Biochemical attributes

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that genotypes (G) and phosphorus amendments (P) interaction significantly (p < 0.001) influenced soil rhizosphere pH during 2016 and 2017 (Supplementary Information, Table S1). In 2016, higher pH was observed in the rhizosphere of Fusion RR genotype amended with inorganic P fertilizer, compared to lowest soil pH observed in the rhizosphere of DKC26-28RIB genotype. However, A4177G3 RIB and DKC23-17RIB genotype exhibited higher and lower soil rhizosphere pH following IP fertilizer in 2017 (Table 1). Phosphatase enzymes hydrolyze various organic and inorganic phosphate esters and played important role in the P-cycle. G × P interaction had significant (p < 0.001) effects on AP-ase activity during 2016 (Table S1). Higher AP-ase was observed when Yukon R was amended with high P2O5 manure, whereas the lowest AP-ase was found in DKC 23-17RIB in control treatment (Table 1). In 2017, G × P interaction had no significant effects on AP-ase (Table S1). However, G × P interaction had significant (p < 0.01) effects on SAP during 2016 (Table S1). Higher SAP level (129.36 mg/kg) was observed when Yukon R was amended with high P2O5 manure, and lowest (49.67 mg/kg) was found when A4177G3RIB genotype was cultivated in control treatment (Table 2). In 2017, G × P interaction had no significant effects on SAP whereas, genotypes and P sources individually had significant effects on SAP (Table S1). Among genotypes, higher SAP was noted in the rhizosphere of Yukon R while the lowest was found in DKC23-17RIB. Among P amendments, both high and low P2O5 manure applications resulted in higher SAP compared to the control treatment (Supplementary information, Table S2).

Total soil carbon and nitrogen

Genotypes and G x P interaction had nonsignificant effects on total soil C during 2016 and 2017 growing seasons, whereas organic and inorganic P amendments exhibited significant changes in total soil C (Table S1). In 2016, P1 and P2 treatments showed 21% and 16% higher total soil C than control (Table 3), whereas, 22% and 12% total soil carbon increase was observed in P1 and P2 treatments compared to control during 2017 (Table 3). Results further demonstrated that genotypes and P amendment exhibited significant effects on total soil N (Table S1). In 2016 and 2017, total soil N (0.31% and 0.33%) was higher in the rhizosphere of Yukon R, whereas lowest total soil N was observed in DKC 23-17 RIB (Table 4). In 2016, P1, P2 and P3 amendment exhibited 30%, 24% and 14% higher total soil N compared to control (Table 1), whereas during 2017, P1, P2 and P3 amendments showed 35%, 19% and 9% higher total soil nitrogen than control (Table 3).

Soil PLFA profiles

ANOVA showed that G × P interaction had no significant effects on active soil microbial community during both years. However, P amendments had significant effects on total PLFA (ΣPLFA), total bacterial PLFA (ΣB-PLFA), gram negative (G−) bacteria, and fungi during 2016 and significantly affected ΣPLFA, ΣB-PLFA, fungi, G−, gram positive (G+) and eukaryotes during 2017 (Table S3). Silage corn genotypes also significantly affected the ΣPLFA, ΣB-PLFA, gram positive (G+), gram negative (G−) bacteria, fungi, eukaryotes, and G+:G− ratio during 2016 and ΣPLFA, ΣB-PLFA, gram positive (G+), gram negative (G−) bacteria, fungi, and F:B ratio during 2017 (Table S3). P1 treatment (DM with high P2O5) enhanced ΣPLFA, ΣB-PLFA, G+, fungal PLFA, and eukaryotes compared to control and IP treatments during 2016, and increased G− bacteria in addition to other microbial attributes mentioned above during 2017 (Fig. 1). Moreover, G × P interaction had significantly (p < 0.01) affected fungi and F:B ratio during 2017 (Table S3). Higher fungal PLFA was observed in the rhizosphere of Yukon R amended with high P2O5 manure (Table S4). Regarding genotypes, Yukon R exhibited significantly higher ΣPLFA and G− compared to other genotypes. Yukon R also produced higher ΣB-PLFA, G+, fungal PLFA and eukaryotes however, statistically at par with DKC26-28RIB during 2016 (Table 4; Fig. 2). In 2017, Yukon R produced lower ΣPLFAs and ΣB-PLFA compared to 2016, but produced higher Σ PLFA, ΣB-PLFA, G−, G+, fungal PLFA and eukaryotes compared to other genotypes. DKC 23-17RIB produced minimum ΣPLFA, ΣB-PLFA, G−, G+, fungal PLFA and eukaryotes among all genotypes during 2017 (Table 4; Fig. 2). It is pertinent to mention here that higher F:B ratio was observed when Fusion RR was amended with low P2O5 manure compared to the lower F:B ratio recorded in the same genotype under control treatment (Table S4). Apparently, it seems that manure application influenced F:B ratio than genotypes.

Variations of the total PLFA (gray wide bars), total bacterial PLFA (white narrow bars), gram negative bacteria (gray wide bars), gram positive bacteria (white narrow bars), fungi (gray wide bars) and eukaryotes (white narrow bars) under organic and inorganic phosphorus fertilizer amendments during 2016 (left) and 2017 (right). Error bars in each graph represents ± SE (n = 3). Different letters above bars indicate significant differences between organic and inorganic phosphorus sources at P < 0.05.

Variations of the total PLFA (gray wide bars), total bacterial PLFA (white narrow bars), gram negative bacteria (gray wide bars), gram positive bacteria (white narrow bars), fungi (gray wide bars) and eukaryotes (white narrow bars) in silage corn genotypes during 2016 (left) and 2017 (right). Error bars in each graph represents ± SE (n = 3). Different letters above bars indicate significant differences among silage-corn genotypes at P < 0.05.

Association between soil biochemical properties and the active microbial population in podzolic soil

Soil pH showed no significant relationship with AP-ase, SAP and soil microbial communities in 2016, whereas significant relationship of soil pH with SAP, G+, G−, ΣB-PLFA and ΣPLFA was observed in 2017 (Table 5). Positive and strong correlations between SAP, AP-ase, G−, eukaryotes, fungi, ΣB-PLFA and ΣPLFA were observed during 2016, whereas, significant and strong positive correlations between SAP, AP-ase, fungi, eukaryotes and F:B ratio were noted during 2017. SAP was significantly and positively correlated with G−, G+, eukaryotes, ΣB-PLFA and ΣPLFA. Likewise, AP-ase showed positive and strong correlation with G−, fungi, eukaryotes, ΣB-PLFA and ΣPLFA during 2016 and with fungi, eukaryotes and F:B ratio during 2017 (Table 5). PCA showed a clear separation of P amendments and genotypes in different quadrants in both years (Fig. 3a,b). Redundancy analysis was carried out between biochemical attributes, PLFAs, P amendments and silage corn genotypes for 2016 and 2017 (Fig. 4). Of the total variation between biochemical attributes and the active microbial community composition, 40.81% and 26.32% was observed in first and second axis respectively, during 2016 (Fig. 4a). In 2017, 40.93% and 18.37% of the total variation in the first and second axis was observed between biochemical, and PLFA parameters (Fig. 4b). Manure amendments (P1 & P2) showed strong and positive relationship with SAP, AP-ase, fungi, G−, total PLFA and total bacterial PLFA in both years which indicates that manure applications either with high or low P2O5 concentration significantly improved SAP, AP-ase and active microbial biomass, community and abundance (Fig. 5a,b). Similarly, Yukon R and DKC26-28RIB showed strong association with G−, total PLFA, total bacterial PLFA, fungi, eukaryotes, SAP, pH and AP-ase compared to other genotypes during 2016 (Fig. 4a). In 2017, Yukon R and DKC26-28RIB showed strong association with total PLFA, G−, total bacterial PLFA, soil pH, SAP, eukaryotes and fungi compared to other genotypes (Fig. 4b).

Redundancy analyses (RDA) of the correlations between biochemical attributes and microbial community composition in silage corn genotypes during 2016 (a), 2017 (b). Arrows with dotted line indicate the genotypes had strong and significant effects on biochemical attributes and arrows with solid line indicate strong and significant effects on microbial community composition (P < 0.05).

Redundancy analyses (RDA) of the correlations between biochemical attributes and microbial community composition between organic and inorganic phosphorus amendments during 2016 (a), 2017 (b). Arrows with dotted line indicate organic and inorganic phosphorus sources had strong and significant effects on biochemical attributes and arrows with solid line indicate strong and significant effects on microbial community composition (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Biochemical attributes

Soil enzymes are instrumental in catalyzing organic matter decomposition reactions and nutrients turnover. Therefore, they can be used as early indicators of land use changes and soil health determinants caused by agricultural practices40. For example, AP-ase and other enzymes activities fluctuate rapidly due to fertilizers application, complex rhizosphere processes, biological properties, and environmental conditions41. Manure contains organic P that is mineralized by phosphatases to IP before plants uptake that; soil microbial and enzyme activities significantly affect P hydrolysis23. Soil and plants microorganisms have evolved several mechanistic means to solubilize bound inorganic P and mobilize organic P through exudation of secondary metabolites such as oxalate and citrate42. In the present study, it seems that root exudates potential vary among the silage corn genotypes, which affected the solubilization of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus, and shaped the microbial community to decompose the manure by secretion of various enzymes. Therefore, we observed higher AP-ase in Yukon R rhizosphere amended with high P2O5 manure and lowest in DKC 23-17RIB genotype cultivated in the control treatment (Table 2). Previous studies also reported that AP-ase activity was stimulated by root exudates and manure application43,44. Increased AP-ase and SAP with high P2O5 manure application in the present study could be attributed to enhanced microbial activities by providing organic sources, such as C, N and P1,16,33. Results of the present study also demonstrate that high P2O5 manure amendment enhanced AP-ase and SAP availability compared to IP and control treatment (Table 2). Pearson’s correlation also showed significant and positive correlation between AP-ase activity and SAP (Table 5).

Soil pH determines the availability of macro and micronutrients42, modify soil physiochemical properties and microbial community composition45. In acidic soils or near neutral soils, manure generally maintain or increase soil pH through liming effect46. Whereas, Dong et al.12 observed that inorganic fertilizers application to soil (alkaline in nature) may return some alkaline substance which may lead to increased soil pH. In the present study, interactive effects of inorganic phosphorus (P3) and silage corn genotypes increased the soil rhizosphere pH, although it was statistically at par with high P2O5 manure (P1 treatment) (Table 1), suggesting that either silage corn roots or microbial communities released specific organic compounds in the rhizosphere that might have altered the soil pH. Shen et al.47 also observed that plant roots exude organic metabolites and some specific signaling compounds, which are key drivers of various rhizosphere processes. Additionally, preferential uptake of cations and anions by different crop genotypes or species under different nutrient regimes might have altered soil rhizosphere pH42,48.

Soil microbial PLFA

Several PLFA based studies reported significant differences in soil microbial community composition and abundance under different fertilizer management practices49,50. Soil microbial community (SMC) are sensitive to external application of N and P51,52. Phosphorus fertilization significantly increased microbial community, diversity and abundance in pastures tropical forest, and grasslands ecosystems51,52. We observed higher ΣPLFA, ΣB-PLFA, and fungi in high P2O5 manure (P1 treatment) than the control and IP treatment (Fig. 1), additionally, organic P amendments stimulated total microbial biomass and AP-ase activities which enhance SAP and silage corn forage production (Fig. 6). Agricultural soils are generally C limited and manure application stimulate the growth of microbes by enhancing SOC, N and P pool in soil (Tables 3, 4), which most probably serve as major energy sources for microorganisms53. In the present study, it seems that high P2O5 manure application not only provided readily available substrate for the microbial community rather other macro and micronutrients particularly high CN (Tables 3, 4), whereas, inorganic P fertilization probably contains small labile organic C which might be not enough to stimulate the substantial growth of microorganisms31. In typical intensively cultivated agricultural soils, bacterial biomass was higher while fungal biomass was lower54. It has been observed that manure application significantly increased G− relative to G+ bacterial biomass, probably due to higher availability of C (Tables 3, 4) over longer periods during the growing season than inorganic fertilization50. Moreover, higher population of G− bacteria usually occur when there is a shift from nutrient deficient condition to nutrient rich conditions, and this pattern was observed in soil amended with P fertilizers55. In the present study, we found significant differences in G− bacterial biomass with low nutrient to rich nutrient manure and IP fertilizer amendment. High P2O5 manure amendment proliferated G− bacterial biomass and was higher than control and IP application in both years (Fig. 1). Role of fungi in agricultural ecosystems is pivotal, particularly in C and nutrient cycling and are sensitive to fertilizers application31. In general, fungal to bacteria ratio is relatively low and is common phenomenon in agricultural ecosystems due to intensive physical disturbance and changes in amount, type and source of fertilizers inputs54,56. In the current experiment, we observed similar pattern of reduced F/B ratios from 0.087–0.094 during 2016 and 0.072–0.084 during 2017 with organic and inorganic P amendments in podzols (Table 6). Our results substantiate the findings of57 who reported lower values for inorganic fertilizers than manure amendments. Particularly, organic amendment (manure) substantially enhanced growth of fungi and thus increased F/B ratios whereas, inorganic mineral source reduced the F/B ratio58. Higher fungal PLFA in manure than in IP fertilizer amended plots (Fig. 1), might be due to additional C added by manure amendment which served as a major source of energy for fungi whereas, inorganic fertilization reduced fungal biomass due to small labile organic C51. In crux, P1 treatment (organic P amendment) exhibited higher total microbial biomass (52.12 nmol g−1 soil), AP-ase activity (50.59 µmol PNP g−1 min−30), SAP and consequently 30% higher forage production than control, whereas, inorganic P amendment showed 47.42 nmol g−1 soil total microbial biomass, 42.24 µmol PNP g−1 min−30 AP-ase activity, 75.27 mg kg−1 SAP and contributed 8% increase in forage production over control (Fig. 6). Enhanced soil microbial biomass, AP-ase, and SAP resulted in higher forage production in organic amended soils compared to control or inorganic P. Organic P amendments increased 14–30% forage production of silage corn whereas only 8% in case of inorganic P as (Fig. 6). Due to the complex soil rhizosphere system and presence of multiple microbial groups, relationship between soil microbes, their abundance and function is not straight forward59. Agricultural management practices may change the dynamics of soil microbial community composition, and function, and eventually crop growth and productivity36,60,61. For instance, different plant species and genotypes release significant number of secondary metabolites in the rhizosphere, which spur the growth of dormant microbial species62,63 A considerable portion (up to 21%) of photosynthetic C as root exudates in the form of soluble sugars, amino acids, or secondary metabolites are utilized by the SMC in the plants rhizosphere64,65,66. Furthermore, a variety of rhizosphere exudates released by plant roots attract specific microbes resulting in alteration of microbial communities and their abundance67,68, as observed in maize genotypes69,70. In the present study, Yukon R might have released some specific organic compounds to attract and select specific microbes, which in turn altered microbial composition and abundance, consequently exhibiting higher ΣPLFA, ΣB-PLFA, and fungi compared to the other genotypes (Table 7). Our results substantiate the findings of71, who reported substantial variation in bacterial richness, diversity and relative abundance in the maize rhizosphere of different inbred lines. Moreover, plants release specific secondary metabolites and organic compounds that shape and drive the microbial structure34,35,36 Furthermore, we observed strong association between ΣB-PLFA, ΣPLFA, soil enzyme (AP-ase), and SAP with Yukon R genotype during 2016. In 2017, Yukon and DKC 26-28RIB showed similar trend with microbial communities and soil biochemical attributes (Fig. 4a,b). To further elucidate and underpin the role of organic compounds released by silage corn genotypes in selecting and attracting specific microbial community and function should be the direction of future research when cultivated on podzolic soils under cool climatic conditions in boreal ecosystem.

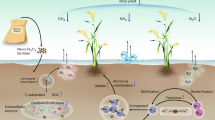

A stylized framework illustrating the effects of organic and inorganic phosphorus amendments stimulating total microbial biomass and acid phosphatase activities, which enhance soil available phosphorus and consequently silage corn forage production. The values are averaged over two growing seasons (2016 & 2017), whereas percent increase forage production in organic and inorganic P amendments was calculated keeping control as base value (P1 – P0/P0 × 100; P2 – P0/P0 × 100; P3 – P0/P0 × 100). The green and orange background shows increase in microbial biomass carbon, acid phosphatase activity, soil available P and forage production in organic and inorganic phosphorus amendments over control.

Conclusion

In two years field research trial, organic and inorganic P amendments significantly influenced the soil biochemical attributes, soil microbial community composition and abundance in silage-corn production systems in podzolic soil under boreal climate. Results suggest that P1 treatment (DM with high P2O5, N and C) significantly enhanced active microbial community composition and abundance, AP-ase, and SAP compared to control and inorganic P amendment. Redundancy analyses also demonstrated strong association among P1 and P2 treatments, AP-ase, SAP, total bacterial PLFA, total PLFA and fungi suggesting that organic P amendment could be a sustainable management practice effective strategy for attaining higher forage yield of silage corn in podzolic soils under boreal climate. Results further suggest that Yukon R and DKC 26-28RIB exhibited higher total PLFA, total bacterial PLFA and fungal biomass, in their soil rhizospheres and showed superior agronomic performance compared to the other genotypes. Taking all together, we can conclude that DM amendment could be a sustainable nutrient management strategy to enhance soil quality, health and forage production of silage corn in podzol soils under boreal climate. We also argue that Yukon R and DKC 26-28RIB genotypes could be good fit to attain higher forage production in boreal climate.

Material and Methods

Experimental design

Field research trials were conducted at Pynn’s Brook Research Station (49.50° N, 57.33° W), Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), Canada during 2016 and 2017 growing season. Soil texture was determined to be characterized with 82% sand, 12% silt, and 6% clay particles (loamy-sand). Soil analyses prior to crop seeding during both study years are given in Table 8. Mean average temperature and rainfall during 2016 and 2017 growing seasons were 12.2 °C, 11.8 °C, and 704 mm and 496 mm, respectively (Fig. 7). The experimental treatments were: 1) DM with high P conc. (P1); 2) DM with low P conc. (P2); 3) Inorganic P (P3); 4) control (P0) and five silage-corn cultivars (Fusion RR, Yukon R, A4177G3RIB, DKC 23-17RIB, and DKC 26-28RIB). Experimental plots were fertilized with dairy manure @ 30,000 L ha−1 considering the local dairy farmer’s practice and mixed in the upper 15-20 cm soil one day before seeding. Triple super phosphate (TSP; 0-46-0) was used as IP source @ 110 kg ha−1. Ammonium nitrate (AN) and murate of potash (MOP) were used as nitrogen (N), and potash (K) source to fulfill the mineral requirement of crop. Full K and half N was applied at seeding, while remaining half N was applied at twelve leaf stage following regional recommendation, soil test report and results obtained from manure analyses reports. It is pertinent to mention here that experimental treatment plots were geo-referenced to keep the same plots during both years of study to avoid any treatment effects. The individual experimental treatment plot was comprised of 3 × 5 m dimensions with four rows of silage corn, and plots were orientated in east-west directions. Experiments were laid-out in randomized complete block design (RCBD) with four replications; however, one replication was omitted from data analysis (Fig. 8). Manure with high and low P2O5 concentrations were chosen after analyzing 13 dairy farms manure samples as organic P source and designated as P1 (high P2O5) and P2 (low P2O5). Detailed dairy manure analysis reports are given in Table 9.

Soil sampling and analysis

A composite soil sample was prepared by gently removing the root adhered soil from three uprooted silage-corn plants in each treatment. The collected soil samples were placed in a cooler containing ice then transported immediately to boreal ecosystems research facility located at Grenfell Campus Memorial University. Composite soil samples were then sieved (2 mm mesh) to remove any debris or inert material and divided into three subsamples. First subsample was dried at 25 °C to determine soil pH and SAP. The second subsample was stored at 4 °C prior to measure the AP-ase activity in rhizosphere and third subsample was stored at −20 °C to determine the active microbial community composition and abundance using phospholipid fatty acid analyses (PLFAs).

Biochemical attributes

Soil pH was determined from air dried soil with calcium chloride (0.01 M) in 1:2 ratio. Soil solution was then mixed for 30 min on an orbital shaker (Innova™ 2300 Platform Shaker, NB, USA) at 120 rpm, then allowed to stand for 1 h and pH readings were recorded with Mettler Toledo, Canada pH meter72. AP-ase activity was measured through determination the p-nitrophenol-phosphate (PNP) as described by73. One mL of 0.09 M citrate buffer was used to extract 100 mg soil sample in 15 mL polypropylene tubes followed by centrifugation at 5000 rpm (10 min). An aliquot (50 µL) of the supernatant was added to 96-well microplate along with PNP (50 µL) and citrate buffer (30 µL). After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, NaOH (20 µL) was dispensed in all wells to terminate the further reaction followed by absorbance recording (450 nm) with BioTek Cytation 3 spectrophotometer. The absorbance was used to calculate the AP-ase in the sample and the values expressed in µM p-nitrophenol g−1 soil min−30. SAP was analyzed using the extraction method described by74. Soil was extracted with Mehlich-3 solution in 1:10 proportion in 50 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. The resulting mixture was then agitated on an orbital shaker at 120 rpm (Innova™ 2300 Platform Shaker, NB, USA) for 5 min. The solution was filtered using Whatman 42 filter papers (Sigma Aldrich, ON. Canada). Aliquots of the filtrate was diluted 50 times then analyzed with an AA3 Continuous Flow Analytical System (AA3HR, SEAL Analytical USA) to determine SAP (mg/kg) level in the root rhizosphere.

Active microbial community assessment

The phospholipid fatty acid (PLFAs) concentrations (nmol g−1) were recorded to assess the active microbial community and abundance in soil samples75,76. Total microbial mass was estimated using the total concentrations of PLFAs (nmol g−1). The PLFAs were then categorized into different taxonomic groups following the published literature on biomarkers (Table 10)77. For this purpose, the 4 g soil was extracted with chloroform methanol (10 mL; 2:1 v/v) in 20 ml glass vials. The samples were homogenized with a sonicator for 5 minutes (amplitude 50; pulse on time: 5 seconds; and pulse off time; 10 seconds) while being cooled simultaneously in an ice bath. The sonicated samples were allowed to settle down at room temperature (24 h). The collected supernatants were then filtered and dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen. Extracted lipids were dissolved in chloroform (2 mL) and neutral lipids, glycolipids and phospholipids were fractioned by solid phase on silicic acid columns (Discovery® DSC- Si SPE tube, 50 µm, 70 Å, 100 mg/mL; ThermoScientific, Brampton, Canada) extraction using chloroform (2.5 mL), acetone (4 mL) and methanol (2.5 mL). The separated phospholipids were then dried under a nitrogen gas stream. The phospholipids were dissolved in methyl tertiary-butyl ether (500 µL) and 100 µL aliquots placed in a screw-cap vials along with trimethyl sulfonium hydroxide (50 µL) as derivatization agent to convert the fatty acids to FAMEs. The sample was then vortexed, mixed (30 sec) for reaction (30 min). Methyl nonadeconate (10 µL; 19:0 @ 160 µg mL−1) was used as internal standard and the samples analyzed with GC-FID (gas chromatography-flame ionization detection) or GC coupled to a tripple quadrouple tandem mass spectrometer (GC-GC/MS-MS) by Trace 1300 gas chromatograph (TSQ 8000 mass spectrometer; ThermoScientific, Brampton, Canada).

Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis with GC-FID

The methylated fatty acids were fractioned with a DB-23 high resolution column (Agilent Technologies, Canada) by supplying helium as carrier (continuous flow rate of 1 mL min−1). Tri-plus auto sampler was used to inject 1 μL of each samples by splitless GC injector mode. The oven temperature varied in time spans (50 °C min; rise to 175 °C considering 20 °C min−1; held for 1 min followed by another rise to 230 °C at the rate of 4 °C and held for 5 min). The commercial standards (NIST database; Thermo Scientific, ON. Canada; Supelco-37 component fatty acid methyl ester mix; bacterial acid methyl ester mixed Sigma Aldrich, ON Canada) were used to identify the methylated PLFAs considering retention time and mass spectra. Methylated PLFA were quantified using internal standards and the results expressed in nmol g−1 soil. We have identified 47 PLFAs whereas, 27 were used to identify and quantify active microbial composition and abundance (Table 10)

Statistical analysis

The effects of P amendments and silage corn genotypes on biochemical attributes and active soil microbial community composition and abundance were assessed. First, the Shapiro-Wilk test was performed to check the normality of the data set on each variable under study. The statistics calculation was conducted using Statistix-10 (Analytical Software, US) with the level of significance set at P < 0.05. P-value smaller than 0.05 indicates that the possibility of assumption is greater than 95%. Association between soil biochemical parameters and microbial community structure was quantified by Pearson’s correlation analyses. Principal component analyses (PCA) and Redundancy analyses (RDA) was performed using XLSTAT (Addinsoft, New York, USA), to assess the effects and relationships of silage corn genotypes and P amendments on soil biochemical parameters and the active soil microbial populations. Sigma plot 14.0 (Systat Software Inc.) and XLSTAT (Addinsoft, New York, USA) were used to make graphs.

References

Zhang, Q. et al. Effects of different organic manures on the biochemical and microbial characteristics of albic paddy soil in a short-term experiment. PLoS One 10, 1–19 (2015).

Yan, X. et al. Carbon sequestration efficiency in paddy soil and upland soil under long-term fertilization in southern China. Soil Tillage Res. 130, 42–51 (2013).

Huang, M., Zhou, X., Cao, F., Xia, B. & Zou, Y. No-tillage effect on rice yield in China: A meta-analysis. F. Crop. Res. 183, 126–137 (2015).

Wang, W., Lai, D. Y. F., Wang, C., Pan, T. & Zeng, C. Effects of rice straw incorporation on active soil organic carbon pools in a subtropical paddy field. Soil Tillage Res. 152, 8–16 (2015).

Drinkwater, L. E. & Snapp, S. S. Nutrients in agroecosystems: rethinking the management paradigm. Adv. Agron. 92, 163–186 (2007).

Mandal, A., Patra, A. K., Singh, D., Swarup, A. & Ebhin Masto, R. Effect of long-term application of manure and fertilizer on biological and biochemical activities in soil during crop development stages. Bioresour. Technol. 98, 3585–3592 (2007).

Wang, Q. et al. Soil chemical properties and microbial biomass after 16 years of no-tillage farming on the Loess Plateau, China. Geoderma 144, 502–508 (2008).

Papadopoulos, A., Bird, N. R. A., Whitmore, A. P. & Mooney, S. J. Does organic management lead to enhanced soil physical quality? Geoderma 213, 435–443 (2014).

Bhattacharyya, R. et al. Conservation agriculture effects on soil organic carbon accumulation and crop productivity under a rice-wheat cropping system in the western Indo-Gangetic Plains. Eur. J. Agron. 70, 11–21 (2015).

Almagro, M. & Martínez-Mena, M. Litter decomposition rates of green manure as affected by soil erosion, transport and deposition processes, and the implications for the soil carbon balance of a rainfed olive grove under a dry Mediterranean climate. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 196, 167–177 (2014).

Yuan, L. et al. Responses of rice production, milled rice quality and soil properties to various nitrogen inputs and rice straw incorporation under continuous plastic film mulching cultivation. F. Crop. Res. 155, 164–171 (2014).

Dong, W. et al. Effect of different fertilizer application on the soil fertility of paddy soils in red soil region of southern China. PLoS One 7, 1–9 (2012).

Yan, F., Schubert, S. & Mengel, K. Soil pH increase due to biological decarboxylation of organic anions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28, 617–624 (1996).

Hirzel, J. & Walter, I. Availability of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium from poultry litter and conventional fertilizers in a volcanic soil cultivated with silage corn. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 68, 264–273 (2008).

Holford, I. C. R. Soil phosphorus: its measurement, and its uptake by plants. Soil Res. Res. 35, 227–240 (1997).

Li, Q. song et al. Biochemical and microbial properties of rhizospheres under maize/peanut intercropping. J. Integr. Agric. 15, 101–110 (2016).

DeBruyn, J. M., Nixon, L. T., Fawaz, M. N., Johnson, A. M. & Radosevich, M. Global biogeography and quantitative seasonal dynamics of Gemmatimonadetes in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6295–6300 (2011).

Perez, L., Nelson, T., Coops, N. C., Fontana, F. & Drever, C. R. Characterization of spatial relationships between three remotely sensed indirect indicators of biodiversity and climate: a 21years’ data series review across the Canadian boreal forest. Int. J. Digit. earth 9, 676–696 (2016).

Tchebakova, N. M., Chuprova, V. V., Parfenova, E. I., Soja, A. J. & Lysanova, G. I. Evaluating the agroclimatic potential of central Siberia in. in Novel Methods for Monitoring and Managing Land and Water Resources in Siberia (eds Mueller, L., Sheudshen, A. K. & Eulenstein, F.) 287–305 (Springer International, 2016).

Prestele, R. et al. Hotspots of uncertainty in land-use and land-cover change projections: a global-scale model comparison. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 3967–3983 (2016).

King, M. et al. Northward shift of the agricultural climate zone under 21st -century global climate change. Sci. Rep. 8, 7904 (2018).

Azeem, K. et al. The Impact of different P fertilizer sources on growth, yield and yield component of maize varieties. Agric. Res. Technol. 13, 1–5 (2018).

Waldrip, H. M., He, Z. & Griffin, T. S. Effects of organic dairy manure on soil phosphatase activity, available soil phosphorus, and growth of sorghum-sudangrass. Soil Sci. 177, 629–637 (2012).

Colvan, S. R., Syers, J. K. & O’Donnell, A. G. O. Effect of long-term fertiliser use on acid and alkaline phosphomonoesterase and phosphodiesterase activities in managed grassland. Biol. Fertil. Soils 34, 258–263 (2001).

Dinesh, R., Srinivasan, V., Hamza, S. & Manjusha, A. Short-term incorporation of organic manures and biofertilizers influences biochemical and microbial characteristics of soils under an annual crop [Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.)]. Bioresour. Technol. 101, 4697–4702 (2010).

Gil-Sotres, F., Trasar-Cepeda, C., Leiros, M. C. & Seoane, S. Different approaches to evaluating soil quality using biochemical properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 37, 877–887 (2005).

White, P. M. & Rice, C. W. Tillage effects on microbial and carbon dynamics during plant residue decomposition. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 73, 138 (2009).

Mikha, M. M. & Rice, C. W. Tillage and manure effects on soil and aggregate-associated carbon and nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 68, 809 (2004).

Lima, A. C. R., Brussaard, L., Totola, M. R., Hoogmoed, W. B. & de Goede, R. G. M. A functional evaluation of three indicator sets for assessing soil quality. Appl. Soil Ecol. 64, 194–200 (2013).

Liu, Z., Rong, Q., Zhou, W. & Liang, G. Effects of inorganic and organic amendment on soil chemical properties, enzyme activities, microbial community and soil quality in yellow clayey soil. PLoS One 12 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Response of soil organic carbon fractions, microbial community composition and carbon mineralization to high-input fertilizer practices under an intensive agricultural system. PLoS One 13, 1–16 (2018).

Geisseler, D. & Scow, K. M. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms - A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 75, 54–63 (2014).

Zhang, Q. et al. Distribution of soil nutrients, extracellular enzyme activities and microbial communities across particle-size fractions in a long-term fertilizer experiment. Appl. Soil Ecol. 94, 59–71 (2015).

Bakker, P. A. H. M., Berendsen, R. L., Doornbos, R. F., Wintermans, P. C. A. & Pieterse, C. M. J. The rhizosphere revisited: root microbiomics. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 165 (2013).

Berendsen, R. L., Pieterse, C. M. J. & Bakker, P. A. H. M. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 478–486 (2012).

Chaparro, J. M., Sheflin, A. M., Manter, D. K. & Vivanco, J. M. Manipulating the soil microbiome to increase soil health and plant fertility. Biol. Fertil. Soils 48, 489–499 (2012).

Sauer, D. et al. Podzol: Soil of the year 2007. A review on its genesis, occurrence, and functions. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 170, 581–597 (2007).

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Canadian Agricultural Services Coordinating Committee. Soil Classification Working Group, National Research Council Canada. The Canadian system of soil classification (No. 1646). NRC Research Press. (1998).

Driessen, P., Deckers, J., Spaargaren, O. & Nachtergaele, F. Lecture notes on the major soils of the world. (2000).

Paz-Ferreiro, J., Trasar-Cepeda, C., Leiros, M. C., Seoane, S. & Gil-Sotres, F. Biochemical properties of acid soils under native grassland in a temperate humid zone. New Zeal. J. Agric. Res. 50, 537–548 (2007).

Paz-Ferreiro, J., Trasar-Cepeda, C., del Carmen Leiros, M., Seoane, S. & Gil-Sotres, F. Intra-annual variation in biochemical properties and the biochemical equilibrium of different grassland soils under contrasting management and climate. Biol. Fertil. Soils 47, 633–645 (2011).

Hinsinger, P. Bioavailibility of soil inorganic P in the rhizosphere as effected by root-induced chemical changes. Plant Soil 237, 173–195 (2001).

Juma, N. G. & Tabatabai, M. A. Effects of Trace Elements on Phosphatase Activity in Soils1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 41, 343346 (1977).

Tarafdar, J. C. & Jungk, A. Phosphatase activity in the rhizosphere and its relation to the depletion of soil organic phosphorus. Biol. Fertil. Soils 3, 199–204 (1987).

Gregory, P. J. & Hinsinger, P. New approaches to studying chemical and physical changes in the rhizosphere: An overview. Plant Soil 211, 1–9 (1999).

Moore, P. A. & Edwards, D. R. Long-term effects of poultry litter, alum-treated litter, and ammonium nitrate on phosphorus availability in soils. J. Environ. Qual. 36, 163–174 (2007).

Shen, J. et al. Phosphorus dynamics: from soil to plant. Plant Physiol. 156, 997–1005 (2011).

Li, Y. F., Luo, A. C., Wei, X. H. & Yao, X. G. Changes in phosphorus fractions, pH, and phosphatase activity in rhizosphere of two rice genotypes. Pedosphere 18, 785–794 (2008).

Ai, C., Liang, G., Sun, J., Wang, X. & Zhou, W. Responses of extracellular enzyme activities and microbial community in both the rhizosphere and bulk soil to long-term fertilization practices in a fluvo-aquic soil. Geoderma 173–174, 330–338 (2012).

Peacock, A. D., Mullen, M. D., Ringelberg, D. B., Tyler, D. D. & Hedrick, D. B. Soil microbial community responses to dairy manure or ammonium nitrate applications. Soil Biol. Biochem. 33, 1011–1019 (2001).

Liu, L. et al. Interactive effects of nitrogen and phosphorus on soil microbial communities in a tropical forest. PLoS One 8 (2013).

Pan, Y. et al. Impact of long-term N, P, K, and NPK fertilization on the composition and potential functions of the bacterial community in grassland soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 90, 195–205 (2014).

Demoling, F., Figueroa, D. & Baath, E. Comparison of factors limiting bacterial growth in different soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 2485–2495 (2007).

Bardgett, R. The biology of soil: a community and ecosystem approach, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198525035.001.0001 (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Tan, H. et al. Long-term phosphorus fertilisation increased the diversity of the total bacterial community and the phoD phosphorus mineraliser group in pasture soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 49, 661–672 (2013).

Mbuthia, L. W. et al. Long term tillage, cover crop, and fertilization effects on microbial community structure, activity: Implications for soil quality. Soil Biol. Biochem. 89, 24–34 (2015).

Ngosong, C., Jarosch, M., Raupp, J., Neumann, E. & Ruess, L. The impact of farming practice on soil microorganisms and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: Crop type versus long-term mineral and organic fertilization. Appl. Soil Ecol. 46, 134–142 (2010).

Buyer, J. S., Teasdale, J. R., Roberts, D. P., Zasada, I. A. & Maul, J. E. Factors affecting soil microbial community structure in tomato cropping systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 831–841 (2010).

Nannipieri, P. et al. Microbial diversity and soil functions. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 54, 655–670 (2003).

Bossio, D. A., Scow, K. M., Gunapala, N. & Graham, K. J. Determinants of soil microbial communities: effects of agricultural management, season, and soil type on phospholipid fatty acid profiles. Microb. Ecol. 36, 1–12 (1998).

Franco-Otero, V. G., Soler-Rovira, P., Hernandez, D., Lopez-de-Sa, E. G. & Plaza, C. Short-term effects of organic municipal wastes on wheat yield, microbial biomass, microbial activity, and chemical properties of soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 48, 205–216 (2012).

Li, X. et al. Functional potential of soil microbial communities in the maize rhizosphere. PLoS One 9, 1–9 (2014).

Szoboszlay, M. et al. Comparison of root system architecture and rhizosphere microbial communities of Balsas teosinte and domesticated corn cultivars. Soil Biol. Biochem. 80, 34–44 (2015).

Badri, D. V. & Vivanco, J. M. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant, Cell Environ. 32, 666–681 (2009).

Badri, D. V., Chaparro, J. M., Zhang, R., Shen, Q. & Vivanco, J. M. Application of natural blends of phytochemicals derived from the root exudates of arabidopsis to the soil reveal that phenolic-related compounds predominantly modulate the soil microbiome. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 4502–4512 (2013).

Chaparro, J. M. et al. Root exudation of phytochemicals in Arabidopsis follows specific patterns that are developmentally programmed and correlate with soil microbial functions. PLoS One 8, e55731 (2013).

Broeckling, C. D., Broz, A. K., Bergelson, J., Manter, D. K. & Vivanco, J. M. Root Exudates Regulate Soil Fungal Community Composition and Diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 738–744 (2008).

Houlden, A., Timms-Wilson, T. M., Day, M. J. & Bailey, M. J. Influence of plant developmental stage on microbial community structure and activity in the rhizosphere of three field crops. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 65, 193–201 (2008).

Bouffaud, M. L. et al. Is diversification history of maize influencing selection of soil bacteria by roots? Mol. Ecol. 21, 195–206 (2012).

Wang, P. et al. Shifts in microbial communities in soil, rhizosphere and roots of two major crop systems under elevated CO2 and O3. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–12 (2017).

Peiffer, J. A. et al. Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 6548–6553 (2013).

Hendershot, W. H., Lalande, H. & Duquette, M. Soil reaction and exchangeable acidity. in In Soil sampling and methods of analysis (eds Carter, M. R. & Gregorich, E. G.) 173–178, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479708006546 (2006).

Tabatabai, M. A. & Bremner, J. M. Use of p-nitrophenyl phosphate for assay of soil phosphatase activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1, 301–307 (1969).

Mehlich, A. Mehlich 3 soil test extractant: A modification of the Mehlich 2 extractant. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 15, 1409–1416 (1984).

Folch, J., Lees, M. & Stanley, G. H. S. Preparation of lipide extracts from brain tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 (1957).

Gomez-brandon, M. L. M. & Dominguez, J. Tracking down microbial communities via fatty acids analysis: analytical strategy for solid organic samples. Curr. Res. Technol. Educ. Top. Appl. Microbiol. Microb. Biotechnol. 1502–1508 (2010).

Moeskops, B. et al. Soil microbial communities and activities under intensive organic and conventional vegetable farming in West Java, Indonesia. Appl. Soil Ecol. 45, 112–120 (2010).

Sheng, M., Hamel, C. & Fernandez, M. R. Cropping practices modulate the impact of glyphosate on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizosphere bacteria in agroecosystems of the semiarid prairie. 1001, 990–1001 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Invariant community structure of soil bacteria in subtropical coniferous and broadleaved forests. Sci. Rep. 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19071 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. Alterations in soil microbial community composition and biomass following agricultural land use change. Sci. Rep. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36587 (2016).

Huygens, D. et al. Drying – rewetting effects on N cycling in grassland soils of varying microbial community composition and management intensity in south central Chile. Appl. Soil Ecol. 48, 270–279 (2011).

Papatheodorou, E. M. et al. Differential responses of structural and functional aspects of soil microbes and nematodes to abiotic and biotic modifications of the soil environment. Appl. Soil Ecol. 61, 26–33 (2012).

Kujur, M. & Patel, A. K. PLFA Profiling of soil microbial community structure and diversity in different dry tropical ecosystems of Jharkhand. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 3, 556–575 (2014).

Wu, Z., Haack, S. E., Lin, W., Li, B. & Wu, L. Soil microbial community structure and metabolic activity of Pinus elliottii plantations across different stand ages in a subtropical area. PLoS One 10, 1–11 (2015).

Brockett, B. F. T., Prescott, C. E. & Grayston, S. J. Soil moisture is the major factor influencing microbial community structure and enzyme activities across seven biogeoclimatic zones in western Canada. Soil Biol. Biochem. 44, 9–20 (2012).

Lasater, A. L., Carter, T. & Rice, C. Effects of drought conditions on microbial communities in native rangelands. (University of Arkansas, 2017).

Kaur, A., Chaudhary, A., Kaur, A., Choudhary, R. & Kaushik, R. Phospholipid fatty acid – A bioindicator of environment monitoring and assessment in soil ecosystem. Curr. Sci. 89, 1103–1112 (2005).

Moreno, J. L., Ondono, S., Torres, I. & Bastida, F. Compost, leonardite, and zeolite impacts on soil microbial community under barley crops. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 17, 214–230 (2017).

Joergensen, R. G. & Potthoff, M. Microbial reaction in activity, biomass, and community structure after long-term continuous mixing of a grassland soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 37, 1249–1258 (2005).

Mckinley, V. L., Peacock, A. D. & White, D. C. Microbial community PLFA and PHB responses to ecosystem restoration in tallgrass prairie soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 37, 1946–1958 (2005).

Schindlbacher, A. et al. Experimental warming effects on the microbial community of a temperate mountain forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43, 1417–1425 (2011).

Buyer, J. S. & Sasser, M. High throughput phospholipid fatty acid analysis of soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 61, 127–130 (2012).

Wu, L. et al. Assessment of shifts in microbial community structure and catabolic diversity in response to Rehmannia glutinosa monoculture. Appl. Soil Ecol. 67, 1–9 (2013).

Zelles, L. Fatty acid patterns of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides in the characterisation of microbial communities in soil: a review. Biol Fertil Soils 111–129 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported by Research & Development Corporation of Newfoundland (RDC-ignite # 5404.1789.101, 2014), and Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA # BDF-208422), Canada. Authors are thankful to Adrian Reid and Danny Brock for assisting in field preparation and seeding of field experiment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. conceived the research idea, managed funding and supervised the overall research project; M.N., V.K. and W.A. performed the layout and seeding of field experiment; W.A., M.N., W.A., S.S.M.G. and S.R.K. assisted in sampling and data collection. R.T., T.H.P., M.Z. and W.A. performed soil and plant analysis. All authors reviewed manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, W., Nadeem, M., Ashiq, W. et al. The effects of organic and inorganic phosphorus amendments on the biochemical attributes and active microbial population of agriculture podzols following silage corn cultivation in boreal climate. Sci Rep 9, 17297 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53906-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53906-8

This article is cited by

-

Salicylic Acid Acts Upstream of Auxin and Nitric Oxide (NO) in Cell Wall Phosphorus Remobilization in Phosphorus Deficient Rice

Rice (2022)

-

Fermented potato fertilizer modulates soil nitrification by shifting the niche of functional microorganisms and increase yield in North China

Plant and Soil (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.