Abstract

We investigated the impact of high pressure and high-temperature annealing on lithium-vanadium-iron-phosphate (LiFe0.75V0.10PO4) glass materials, proposed for the use in cathodes for high-performance batteries. The treatment was carried out below the glass transition temperature (Tg ≈ 483 °C) at P = 1 GPa pressure, in an argon atmosphere. It led to the multifold electrical conductivity increase. Broadband dielectric spectroscopy (BDS) measurements before and after the process revealed the strong DC-conductivity increase across the whole studied frequency range by two orders of magnitude. The phenomenon is explained using Mott’s theory of polaron hopping in disordered solids containing transition metal oxides. The pressure evolution of the glass transition temperature and the crystallisation temperature above Tg is shown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The change of the transportation systems towards electric cars fleet and inherently intermittent nature of many renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind electric power, requires breakthroughs in the development of innovative batteries characterised by a higher power and energy density matched with lower costs. Since lithium-iron-phosphate (LiFePO4) was indicated theoretically by Goodenough et al.1 to have a high electrochemical capacity, it became one of the most promising materials for Li-ion battery cathodes. However, its practical performance remains limited due to the relatively low electronic conductivity. This severe drawback has been addressed by numerous approaches, mainly based on carbon additives, structural modifications, and doping2,3,4. Whittingham et al.5 showed that small addition of vanadium has a positive impact on its gravimetric capacity. The following notable possibility offers the application of materials in the amorphous state instead of the crystalline one. The use of amorphous/glass material for electrodes results in isotropic properties avoids the detrimental role of grain-boundaries. Furthermore, glasses have ‘open structure’ with larger free volume, and they are characterised by the decoupling between ionic conduction and the structural mode relaxation6,7. To increase the electric conductivity of such glasses, Garbarczyk et al.8,9 developed the novel way of preparation of the electrodes, in which the increase of the electric conductivity is associated with the nucleation of nano-crystallites within the amorphous matrix. In particular, this method led to a giant (9 orders of magnitude) increase in electrical conductivity of LiFe0.75V0.10PO4 glass due to its thermal nano-crystallisation10. The nano-crystallisation was achieved by an exploration of the characteristic feature of glass-forming systems that exhibit a crystallisation zone in the ultraviscous domain above glass transition temperature Tg, that emerges upon heating from the solid glass state11,12. In particular, rapid heating followed by a subsequent quench led to the formation of the composite system with LiFe0.75V0.10PO4 nano-crystallites within the residual solid amorphous matrix.

The mechanism of the observed significant increase of electric conductivity was explained within the classical Mott’s theory of electron (polaron) hopping in oxide glasses containing transition metal oxides (e.g., Fe and V)13, which was also adopted to nanomaterials14. In this approach, electrical conductivity is given by the formula13,14:

where R is the average distance between hopping centres, α is the inverse localisation length of the electron wave function, c is the fraction of occupied hopping sites for electrons (e.g., Fe2 + or V4 + ions), and Ea is the activation energy of electronic conduction.

The activation energy can be expressed by13,14

where wD is the average difference in energy of the two hopping centres caused by a disorder (e.g., in glassy or nano-crystalline material), εp – relative electric permittivity of a polaron, up – its radius.

As indicating by Eqs (1) and (2) the composition and the structure of materials play a significant role in the electrical conductivity because they affect the average distance between hopping centres R and their concentration c. Furthermore, shells of nano-grains have a significant volumetric impact on the charge transfer process, due to strongly disordered interfacial regions which are characterised by higher densities of hopping centres. The disordered interfacial structure and small values of R might explain significantly higher values of electrical conductivity and lead to lower activation energies.

To investigate further the above-described hopping conductivity mechanism and the possibility of achieving even higher electrical conductivity increases, in this work we focus on the impact of compressing on electrical properties of LiFe0.75V0.10PO4 glasses and its nano-crystallite–glass composites.

In general, high pressures can lead to unique, and often exotic features15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 such as the appearance of metallic hydrogen phase20,21 or polymeric nitrogen22,23. While these phenomena are scientifically fascinating, they often require pressures of the order hundreds of GPa, i.e., similar to those present in the centre of the Earth. The practical use of the pressure path pressure for the development of new materials has to address 3 essential problems: (i) pressures leading to significant effects are often within extreme, multi-GPa, domain, (ii) such extreme-pressures compression limits the number of transformed materials to few milligrams, (iii) unique properties disappear when returning to ambient conditions15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. However, there is a notable exception to these limitations. Recently, it was shown that in the case of oxide glasses the high pressure (HP, ~1–2 GPa) and high temperature (HT, 600–800 °C) annealing at the adequately selected temperatures below the glass transition temperature Tg could permanently increase the glass density, the surface hardness and the cracking-resistance24,25,26.

Therefore, in this work, we examine the potential of combining the high-pressure and high-temperature annealing with the nano-crystallisation scheme recalled above for glassy LiFe0.75V0.10PO4 glasses.

Results and Discussion

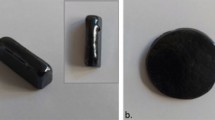

Glassy samples were synthesised from inorganic pre-dried precursors according to the routine described in detail in ref.27, providing melting in the inert atmosphere and fast cooling with melt-quenching technique. This process resulted in a reference glassy sample processed at atmospheric pressure (P = 0.1 MPa). Subsequently, such sample was pressurised at P = 1GPa, at a temperature just below Tg(P), then it was fast heated up to Tcryst(P) and later fast cooled down to Tg(P) − 50 K where the sample was annealed for Δt = 2hours. Finally, the sample was cooled to room temperature.

For the differential thermal analysis (DTA, Fig. 1) under high pressure and temperature, glassy samples were placed into a graphite melting pot. During this process, the composite (amorphous matrix + nano-crystallites) appeared.

Subsequently, high-pressure and high-temperature (HP-HT) studies were carried to reveal the glass transition temperature and the crystallisation domain dependence as the function of pressure. These results, obtained via the differential thermal analysis (DTA) under pressure, are shown in Fig. 2. The glass transition temperature and the maximal crystallisation follow the following dependencies: Tg = 57.5P + 432.5 (°C) and the temperature Tcr.78.5P + 488.5 (°C). Borders of the crystallisation zone are indicated in Fig. 2. The HP-HT annealing discussed below took into account conditions defined by Fig. 2, within the P-T plane.

Figure 3 shows the results of XRD analysis of samples after the temperature formation under atmospheric pressure and after the HP-HT annealing. One can conclude that nano-crystalline samples after pressurising exhibited a structure of lithium-iron-phosphate olivine with impurities of NASICON-like Li3Fe2(PO4)3 phase. The amount of the impurities was considerably lower in the sample heat-treated at the high-pressure P = 1 GPa. XRD results suggest that changes in the conductivity are caused by microscopic charge transfer mechanism based on electron hopping. These results are consistent with the activation energy comparison for both samples, presented below. According to Eq. (2) compressing can induce the increase of the electric conductivity, what is associated with the decrease of the activation energy, itself related to the decrease in an average distance between hopping centres (R).

The frequency dependences of the electric conductivity after the ‘standard’ thermal treatment under atmospheric pressure and after the HP-HT treatment are shown in Fig. 4. Both samples exhibit the ‘universal’ pattern of electric conductivity for ionic, conductive, systems28,29:

where the horizontal low-frequency part is related to DC electric conductivity.

Electric conductivity as the function of frequency for LiFe0.75V0.10PO4 glassy composite system: the amorphous, glass matrix + nano-crystallites with the olivine structure at a temperature T = 100 °C. Results are for the thermal treatment at the atmospheric pressure P = 0.1 MPa  and for the pressure processing at P = 1 GPa

and for the pressure processing at P = 1 GPa  , as described in the report. The horizontal part is for the DC electric conductivity. The inset shows the derivative of experimental data from the central part of the given figure, to show fine details of the behaviour.

, as described in the report. The horizontal part is for the DC electric conductivity. The inset shows the derivative of experimental data from the central part of the given figure, to show fine details of the behaviour.

The analysis of the data in the power-law regions using the linear regression fit in the logarithmic scale part yielded exponents n ≈ 0.80 for P = 0.1MPa and n ≈ 0.88 as shown by blue and red lines. The low-frequency plateaus in Fig. 4 represent DC electric conductivity. Remarkably, there is a dramatic increase from \({\sigma }_{DC}^{0.1MPa}\approx 2.89\cdot {10}^{-8}\) S·cm−1 to \({\sigma }_{DC}^{1GPa}\approx 1.51\cdot {10}^{-6}\) S·cm−1 due to the above described HP-HT treatment. Moreover, the HP-HT treatment extends the DC electric conductivity domain. Its onset for the thermal treatment at P = 0.1 MPa is related to fon ≈ 100 Hz where after the HP-HT treatment fon ≈ 5 kHz.

The inset in Fig. 4 shows the derivative of experimental data from the central part of the plot, yielding the distortion-sensitive insight into its frequency dependence. The most notable features are that it reveals the significant violation of Josher’s ‘universal’ scaling28,29 relation for the frequency-dependent ‘DC part’ of electric conductivity, which according to Eq. (3) should manifest itself via the horizontal dependence with the value related to the exponent n. This means that the scaling’ behaviour in the main part of the plot should be treated instead as the ‘effective’ portrayal. Regarding the DC conductivity, the expected constant value of electric conductivity, i.e. d log10σ(f)/d log f = 0, occurs only for the HP-HT processed sample. For the samples, processed under atmospheric pressure, there is the small upward shift showing that is the case of the ‘almost-DC’ samples with ∼σDC ∝ f1.02.

Figure 5 shows the temperature evolution of the DC conductivity showing the clear Arrhenius type evolution:

where Ea stands for the activation energy.

Notable, that after HP-HT treatment, the activation energy is equal to 44% of the one observed the one noted due to the temperature treatment under atmospheric pressure.

Concluding, this report presents the first-ever pressure dependence of the glass transition temperature and the crystallisation temperature (Tcr. > Tg) for the Li-ion based glass formers. The new way of treatment of LiFe0.75V0.10PO4 glass matrix + nano-inclusions with olivine structure based on the HP-HT treatment led to the appearance of a set of favourable for applications features, in comparison with the standard treatment under atmospheric pressure. Notable is the range of applied temperatures and pressures, enabling the direct scaling at least to the pilot scale. All these indicate that the application of the properly designed high-pressure/high-temperature treatment can be considered as the new way in the challenge for innovative batteries solutions.

Methods

We used Novocontrol Alpha Impedance Analyzer (model 2015 or broadband dielectric spectroscopy (BDS) measurements over the frequency range 10−1Hz < f107Hz. Samples were placed between two flat-parallel capacitor’s plates made from Invar with a diameter 2r = 10 mm and a thickness d = 1 mm and using a measurement voltage U = 1V. The high-pressure (HP) and high-temperature (HT) processing were carried out using large-volume (V ~1 L) HP-HT facilities with gas nitrogen (N2) medium designed and built within IHHP PAS with a protocol described in refs24,25,26.

References

Padhi, A. K., Nanjundaswamy, K. S. & Goodenough, J. B. Phospho-olivines as positive-electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 1188–1194 (1997).

Chekannikov, A. A. et al. Research of Lithium Iron Phosphate as Material of Positive Electrode of Lithium-Ion Battery. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 11, 2219–2229 (2016).

Hagberg, J. et al. Lithium iron phosphate coated carbon fibre electrodes for structural lithium-ion batteries. Comp. Sci. and Technol. 162, 235–243 (2018).

Hu, L.-H., Wu, F.-Y., Lin, C.-T., Khlobystov, A. N. & Li, L.-J. Graphene-modified LiFePO4 cathode for lithium-ion battery beyond theoretical capacity. Nat. Comm. 4, 1687 (2013).

Omenya, F. et al. Can vanadium be substituted into LiFePO4. Chem. Mat. 23, 4733–4740 (2011).

Afyon, S., Krumeich, F., Mensing, C., Borgschulte, A. & Nesper, R. New High Capacity Cathode Materials for Rechargeable Li-Ion Batteries: Vanadate-Borate Glasses. Sci. Rep. 4, 7113 (2014).

Braga, M. H., Murchison, A., Ferreira, J. A., Singh, P. & Goodenough, J. B. Glass-Amorphous Alkali-Ion Solid Electrolytes and Their Performance in Symmetrical Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 948–954 (2016).

Pietrzak, T. K. et al. Electrical properties vs. microstructure of nanocrystallized V2O5-P2O5 glasses. J. Power Sources 194, 73–80 (2009).

Pietrzak, T. K., Wasiucionek, M., Michalski, P. P., Kaleta, A. & Garbarczyk, J. E. Highly conductive cathode materials for Li-ion batteries prepared by thermal nanocrystallization of selected oxide glasses. Mat. Sci. and Engin. B 213, 140–147 (2016).

Garbarczyk, J. E. et al. High electronic conductivity in nanostructured materials based on lithium-iron-vanadate-phosphate glasses. Solid State Ionics 272, 53–59 (2015).

Rzoska S. J. & Mazur V. (eds.). Soft Matter under Exogenic Impacts (Springer, Berlin, 2007).

Rzoska, S. J., Mazur, V. & Drozd-Rzoska A. (eds.), Metastable Systems under Pressure (Springer Verlag, Berlin, 2010).

Mott, N. F. Electrons in disordered structures. Adv. Phys. 50, 865–945 (2001).

Pietrzak, T. K. et al. Nature of electronic conductivity in olivine-like glasses and nanomaterials of Li2O-FeO-V2O5-P2O5 system. Solid State Ionics 302, 45–48 (2017).

Chen, J. Lower-mantle materials under pressure. Science 351, 122–123 (2016).

Walsh, J. P. S. & Freedman, D. E. High-Pressure Synthesis: A New Frontier in the Search for Next-Generation Intermetallic Compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 1315–1323 (2018).

Amsler, M., Hegde, V. I., Jacobsen, S. D. & Wolverton, C. Exploring the high-pressure materials genome. Phys. Rev. X 8, 041021 (2018).

Li, B. et al. Diamond anvil cell behaviour up to 4 Mbar. Proc. Natl. Soc. USA 115, 1713–1717 (2018).

Tyagi, A. K. & Banerjee, S. Materials Under Extreme Conditions. Recent Trends And Future Prospects (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2017).

Dias, R. P. & Silvera, I. F. Observation of the Wigner-Huntington transition to metallic hydrogen. Science 355, 715–718 (2017).

Ball, P. Metallic hydrogen in the spotlight. Nat. Mat. 16, 288 (2017).

Eremets, M., Gavriliuk, A., Trojan, I., Dzivenko, D. & Boehler, R. Single-bonded cubic form of nitrogen. Nat. Mat. 3, 558 (2004).

Li, Y. et al. Route to high-energy density polymeric nitrogen t-N via He−N compounds. Nat, Comm, 9, 722 (2018).

Smedskjaer, M. M., Bauchy, M., Mauro, J. C., Rzoska, S. J. & Bockowski, M. Unique effects of thermal and pressure histories on glass hardness: Structural and topological origin. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 164505 (2015).

Januchta, K. et al. Discovery of Ultra-Crack-Resistant Oxide Glasses with Adaptive. Networks. ACS Chem. Mat. 29, 5865–5876 (2017).

Kapoor, S. et al. Combining high hardness and crack resistance in mixed network glasses through high-temperature densification. Phys. Rev. Matt. 2, 063603 (2018).

Pietrzak, T. K., Wasiucionek, M., Gorzkowska, I., Nowiński, J. L. & Garbarczyk, J. E. Novel vanadium-doped olivine-like nanomaterials with high electronic conductivity. Solid State Ionics 251, 40–46 (2013).

A. K. Jonsher, Dielectric Relaxation in Solids (Chelsea Dielectrics Press., London, 1983).

Habasaki, J., Leon, C. & Ngai, K. L. Dynamics of Glassy, Crystalline and Liquid Ionic Conductors (Springer, Berlin 2017).

Acknowledgements

Work or PK, SR and SS was supported by the Polish National Science Centre POLONEZ program which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 665778. Works of AD-R was supported by the NCN OPUS grant 2017/25/B/ST3/02458.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P. B. and T.K.P. prepared the glassy sample. M.B. carried out high-pressure treatment. S.S. measured electrical parameters using BDS method. S.S., A.D.R., S.J.R. and P.K. analyzed data and wrote the main part of this manuscript. T.K.P. and J.E.G. discussed the data, basing on Mott’s model.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baranowski, P., Starzonek, S., Drozd-Rzoska, A. et al. Multifold pressure-induced increase of electric conductivity in LiFe0.75V0.10PO4 glass. Sci Rep 9, 16607 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53232-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53232-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

for glass-forming LiFe0.75V0.10PO4. Dashed lines indicate the borders of the crystallisation zone.

for glass-forming LiFe0.75V0.10PO4. Dashed lines indicate the borders of the crystallisation zone.