Abstract

Male infertility might be caused by genetic and/or environmental factors that impair spermatogenesis and epididymal sperm maturation. Here we report that heterozygous deletion of the nuclear receptor coactivator-5 (Ncoa5) gene resulted in decreased motility and progression of spermatozoa in the cauda epididymis, leading to infertility in male mice. Light microscopic and ultrastructural analysis revealed morphological defects in the spermatozoa collected from the cauda epididymis of Ncoa5+/− mice. Immunohistochemistry showed that interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression in epithelial cells of Ncoa5+/− epididymis was higher than wild type counterparts. Furthermore, heterozygous deletion of Il-6 gene in Ncoa5+/− male mice partially improved spermatozoa motility and moderately rescued infertility phenotype. Our results uncover a previously unknown physiological role of NCOA5 in the regulation of epididymal sperm maturation and suggest that NCOA5 deficiency could cause male infertility through increased IL-6 expression in epididymis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Male fertility counts on effective production of mature spermatozoa that is capable of fertilizing the egg. Infertility affects about 10 to 15% couples worldwide, about 50% of which are attributed to male fertility defects, mostly due to abnormal spermatogenesis1,2. Spermatogenesis is a complex stepwise sequence of events in which spermatogonia develop into mature spermatozoa, also called sperm cells, through the path of mitosis and meiosis in the seminiferous tubules of the testes3. Spermatozoa subsequently travel to the caput and the corpus of epididymis where sperm maturation takes place. Finally, the sperm cells are stored in the cauda epididymis. After spermatogenesis, sperm are morphologically complete but immotile and unable to carry out oocyte fertilization4. It is only after the transit through the epididymis that the spermatozoon acquires its fertilization ability5, by undergoing a discrete series of post-gonadal differentiation stages controlled by the surrounding epididymal environment. Such extracellular control of gamete differentiation is called epididymal sperm maturation6.

The processes of spermatogenesis and sperm maturation are influenced by numerous local factors including hormone fluctuation and aberrant productions of cytokines due to metabolic syndromes and infectious diseases5,7,8,9. Accumulating evidence suggests that cytokines produced and secreted by inflammatory cells in the male urogenital tract can disturb sperm function and motility. Especially, chronic epididymitis leads to decreased sperm count and motility and is more related to male fertility than inflammation or infection of prostate and seminal vesicles10. Of particular interest is interleukin 6 (IL-6) that is a multifunctional cytokine involved in both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory actions11. It is mainly expressed in immune cells including monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes, but also expressed in many non-immune cells such as epithelial cells, astrocytes, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells and fibroblasts in various tissues12. IL-6 was found to be expressed in spermatogonia, spermatocytes and interstitial cells in the testicular tissues of both immature and mature mice and its expression was decreased in testicular tissues of mature mice as compared to immature mice13. Human sperm cells were demonstrated to be capable of secreting IL-6. The production of IL-6 by testicular cells and its presence in seminal fluid have implicated IL-6 in the regulation of growth, differentiation and function of sperm. Indeed, IL-6 was reported to significantly reduce progressive motility at higher concentrations in a dose- and time-dependent manner14. IL-6 has been suggested to inhibit DNA synthesis in meiotic spermatocytes and spermatogonia within the seminiferous epithelium of rat15. Moreover, increased IL-6 in the semen has been reported in infertile men with varicocele16 and patients with infection of accessory genital glands17. However, little is known regarding the expression and function of IL-6 in the epididymis.

Nuclear receptor co-activator 5 (NCOA5) is a unique nuclear receptor co-activator with both co-activation and co-repression functions and regulates transcriptional activities of nuclear receptors such as estrogen receptors and liver X receptor18,19,20. Our previous study showed that NCOA5 is involved in the regulation of IL-6 transcription in liver Kupffer cells21. Ncoa5+/− male mice developed glucose intolerance, hepatic steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which can be partially reversed by heterozygous deletion of Il-6 gene21,22. Intriguingly, we observed that Ncoa5+/− male mice were barely able to father litters when mated with female mice, while Ncoa5+/−Il6+/−male mice could. Thus, we aimed to determine whether heterozygous deletion of Ncoa5 affects sperm development and whether IL-6 expression mediates the effect of NCOA5 on fertility of male mice.

Results

Heterozygous deletion of Ncoa5 results in decreased sperm mortality and infertility in male mice

Since Ncoa5−/− mice were not generated by breeding genetically-engineered Ncoa5+/− male and female mice21, we explored whether heterozygous deletion of Ncoa5 causes mouse infertility. According to the data in the Human Protein Atlas (www.proteinatlas.org), NCOA5 is expressed in seminiferous ducts and Leydig cells in testis, as well as in epithelial cells in the epididymis. To this end, we first compared expression of NCOA5 in the testis and epididymis between Ncoa5+/+ and Ncoa5+/− male littermates using Western blot. As expected, we found that the protein levels of NCOA5 in Ncoa5+/− testis were decreased (Fig. S1A,B). To determine the fertility of Ncoa5+/− male mice, we bred a group of wild-type (WT) and Ncoa5+/− male littermates with Ncoa5+/− female mice over a period of 6 months. Although, there were about 13% of Ncoa5+/− male mice (4/30) that were able to father a litter with 2–4 pups per litter at their earlier ages, the majority of Ncoa5+/− male (26/30) mice at ages of 2–8 months were not able to father a litter, whereas all Ncoa5+/+ male mice were able to father multiple litters with 5–8 pups per litter (Fig. 1A). Even when bred with wild type female mice, just about 30% of Ncoa5+/− male mice (3/10) were capable of fathering a litter (Fig. 1A). In contrast to Ncoa5+/− males, Ncoa5+/− females are fertile, as they were used for maintaining the Ncoa5+/− breeding colony. This result indicates that the fertility of Ncoa5+/− male mice is severely impaired. Analysis of sperm isolated from cauda epididymis showed that the concentration of sperm in WT and Ncoa5+/− males is comparable (Fig. 1B). However, the percentage of motile sperm, as well as the percentage of progressively motile sperm, are significantly decreased in Ncoa5+/− male mice compared to age-matched WT males (Fig. 1C,D). Taken together, these results suggest that Ncoa5+/− male mice are infertile, at least in part, due to a decrease in the number of motile sperm.

Ncoa5+/− male mice were infertile. (A) Percentages of fertile WT (n = 30) or Ncoa5+/− (n = 30) male mice bred with Ncoa5+/− female mice and percentage of fertile Ncoa5+/− (n = 10) male bred with WT female mice for 6 months. n = the number of mice. Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, **P < 0.01, N.S.: no significance. (B) Comparison of cauda epididymis sperm concentrations between 4-month-old WT (n = 3) and Ncoa5+/− male mice (n = 3). n = the number of mice. Values are mean ± SEM, N.S.: no significance. (C) Comparison of percentages of motile sperm of 4-month-old WT (n = 3) and Ncoa5+/− male mice (n = 3). n = the number of mice. Values are mean ± SEM, **P < 0.01. (D) Comparison of percentages of progressive sperm of 4-month-old WT (n = 3) and Ncoa5+/− male mice (n = 3). n = the number of mice. Values are mean ± SEM, **P < 0.01. (E) Phase contrast images of sperm collected from 4-month-old WT and Ncoa5+/− mice. Red arrows indicated the abnormal head of Ncoa5+/− male sperm. Sybr green stains the head of the sperm, while Mito track stains the mitochondria of the sperm. (F) Percentages of sperm with normal head in WT (n = 3) and Ncoa5+/− male mice (n = 3). n = the number of mice. Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Ncoa5 +/− male mice display abnormal sperm morphology

We next examined the gross anatomy and histology of H & E stained sections of WT and Ncoa5+/− testes. WT and Ncoa5+/− mice displayed comparable testis size and weight. No significant differences in histology of H & E stained sections were observed between the WT and Ncoa5+/− testes (Fig. S2A). However, when the spermatozoa collected from the cauda epididymis were examined under the phase contrast microscope, a significant proportion of spermatozoa from Ncoa5+/− mice apparently displayed abnormal morphology compared with Ncoa5+/+ sperm (Fig. 1E,F). Sybr green and Mito track staining of sperm showed that the heads of many Ncoa5+/− sperm were misshapen as compared with WT sperm (Fig. 1E). To uncover structural defects in Ncoa5+/− sperm, we compared the ultra-structure of Ncoa5+/− sperm with that of WT sperm using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Under SEM, the heads of some of Ncoa5+/− sperm, in contrast to those of Ncoa5+/+ controls (Fig. 2A), appeared to have roughly uneven surface and bend over with the tip of the head toward the tail or to curl like a “golf stick” (Fig. 2B). Some of Ncoa5+/− sperm curled as a disk-like structure by wrapping around the head with the neck and middle parts of the tail (Fig. 2B–D). In aid of the observations with light microscopic and SEM, TEM showed that the middle piece consists of disrupted mitochondria and axoneme wrapped around the bent head and neck of Ncoa5+/− sperm compared to the head of WT sperm (Fig. 2E–H). In addition, we determined where the sperm developed the abnormal morphology. TEM analysis showed that the morphology of Ncoa5+/− sperm collected from testis was comparable to that of WT (Fig. 3A,B). However, Ncoa5+/− sperm harvested from caput epididymis had started to exhibit abnormal morphology (Fig. 3C,D). Furthermore, the Ncoa5+/− sperm collected from corpus epididymis had severe deformed morphology compared to that of WT sperm (Fig. 3E–H). Therefore, Ncoa5+/− sperm appear to acquire the abnormal morphology in the course of the post-gonadal stages of sperm differentiation during transit from the head to the tail of the epididymis, while the morphological structure of epididymis was comparable in Ncoa5+/− and Ncoa5+/+ male mice (Fig. S3).

Ultrastructure analyses of WT and Ncoa5+/− sperm. (A–D) Representative SEM analytic images of WT (A) and Ncoa5+/− epididymal sperm (B–D). Inserts are the higher magnification images of the head and neck region of the sperm. Scale bars: 5 μm (A,B); 1 μm (C,D); inserts: 1 μm. (E–H) Representative TEM analytic images of WT (E) and Ncoa5+/− epididymal sperm (F–H). Scale bars: 1μm. Cross-section of the cytoplasmic droplet (CD) of a WT spermatozoon (E). 1: Outer membrane of the CD; 2: middle piece of the sperm containing mitochondrial sheath and axoneme; 3: vacuoles within the CD; Cross-sections of Ncoa5+/− bent sperm head and neck region wrapped around by the tail (F–H). 4: nucleus; 5: middle piece containing mitochondria and axoneme wrapped around the bent head and neck; 6: disrupted mitochondria of the middle piece; 7, 8 and 9: outer membrane of the droplet; 10 and 11: acrosome; 12 and 13: wrapped-around middle piece containing mitochondria and axoneme; 14: large membranous vacuoles.

Representative TEM images of Ncoa5+/− sperm from different parts of the urinary tract. (A,B) Representative TEM images of sperm from testis showed comparable morphology between WT (A) and Ncoa5+/− (B), Scale bars (A): 1μm, (B): 2 μm, (C,D) TEM images of sperm from WT (C) and Ncoa5+/− (D) caput epididymis. Scale bars (C,D): 2 μm, (E–H) TEM images of sperm from WT (E) and Ncoa5+/− (F–H) corpus epididymis, lower magnification (E,F), higher magnification (G,H). Scale bars (E,F): 5 μm, (G,H): 1μm. Red arrow indicates the abnormal morphology of sperm in Ncoa5+/− epididymis.

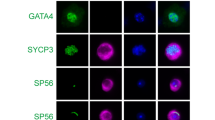

Expression of IL-6 in the epithelium was increased in Ncoa5 +/− epididymis

We previously reported that the mRNA and protein levels of IL-6 were elevated in the liver of Ncoa5+/− male mice and that heterozygous deletion of Il-6 gene rescued glucose intolerance and hindered HCC development in Ncoa5+/− male mice21. We therefore compared IL-6 expression in the epididymis between Ncoa5+/+ and Ncoa5+/− male mice using Western blot and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses. Expression of IL-6 was significantly increased in epididymis of Ncoa5+/− male, compared to epididymis of age-matched Ncoa5+/+ male mice (Figs 4A,B). IL-6 IHC staining in the epithelium was significantly increased in the caput, corpus and cauda of the epididymis of Ncoa5+/− male mice (Fig. 4C,g–l) compared with those of Ncoa5+/+ male mice (Fig. 4C,a–f), whereas no apparent IL-6 IHC staining was detected in both Ncoa5+/+ and Ncoa5+/− testes (Fig. S5). These results suggest that IL-6 expression is elevated in the epithelial cells of the epididymis in the Ncoa5+/− mice.

IL-6 expression in epididymis of WT and Ncoa5+/− male mice. (A) Western blot analysis of IL-6 expression in epididymis of age-matched 13–15 months old WT (n = 5, lanes 1–5) and Ncoa5+/− (n = 6, lanes 6–11) male mice using anti-IL-6 and anti-β-actin antibodies. Each lane represents a single tissue lysate of the whole epididymis from a mouse. Cropped blots from the same gel are shown. Uncropped blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4. The same blot membrane was stripped and blotted with the same method except without adding the primary antibodies as control (Supplementary Fig. S4C). (B) Quantification of data from (A). n = the number of mice. **P < 0.01. Error bar ± SEM. (C) Representative IL-6 IHC staining of WT, Ncoa5+/− and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mouse epididymides. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on epididymis from 4.5 months old WT (n = 2), Ncoa5+/− (n = 3) and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− (n = 3) male mice using an anti-IL-6 antibody. n = the number of mice. Representative IL-6 IHC staining images of WT (a–f), Ncoa5+/− (g–l) and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− (m–r) epididymal caput (segments 1–2) at lower (a, g and m) and higher (b, h and n) magnification, corpus (segments 7) at lower (c, i and o) and higher (d, j and p) magnification, and cauda (segments 8–9) at lower (e, k and q) and higher (f, l and r) magnification. Black squares specify the areas that are magnified and displayed as high magnification pictures. Scale bars: 50 µm. Immunohistochemical analysis without using IL-6 antibody was performed on epididymis from an Ncoa5+/− mouse and a representative image is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

Heterozygous deletion of Il-6 improves fertility of Ncoa5 +/− male mice

To determine whether increased IL-6 expression is responsible for the phenotypes observed in Ncoa5+/− mice, we generated mice bearing dual heterozygous deletions of Il-6 and Ncoa5 genes by crossing Ncoa5+/− with Il-6−/− (B6.129S6-Il-6tm1Kopf) mice. As expected, IHC staining showed that the epididymal expression of IL-6 was apparently reduced in Ncoa5+/− Il-6+/− mice (Fig. 4Cm–r). Strikingly, we found that 5 out of 6 Ncoa5+/− Il-6+/− male mice were able to father litters with 2 to 8 pups per litter when mating with Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− female mice (Fig. 5A), in contrast to Ncoa5+/− male mice shown in Fig. 1A. Analysis of epididymal cauda sperm revealed that sperm from Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice displayed both increased motility and progressive motility compared to age-matched Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/+ male sperm (Fig. 5C,D). As expected, there was no significant difference in the sperm concentration between Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/+ (Fig. 5B). Consistent with increased and progressive motility, the ultrastructure of sperm from Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice appeared to be significantly improved as shown by the SEM and TEM scanning analyses (Figs 5E–H and 6). These results suggest that the phenotypes of morphologically abnormal sperm and poor fertility observed in Ncoa5+/− male mice were due, at least in part, to IL-6 overexpression in the epididymis.

Heterozygous Il-6 deletion improves fertility and sperm morphology of Ncoa5+/− male mice. (A) Percentages of fertile Ncoa5+/+Il-6+/+ male mice or Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice bred with Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− female mice for six months. White bar, Ncoa5+/+Il-6+/+ male mice (n = 7). Black bar, Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice (n = 6). n = the number of mice. Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, N.S.: no significance. (B) Epididymal cauda sperm concentrations of 4-month-old Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/+ and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice (n = 3). n = the number of mice. N.S.: no significance. (C) Percentage of motile sperm of 4-month-old Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/+ and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice (n = 3). (D) Percentage of progressive sperm of 4-month-old Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/+ and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice (n = 3). n = the number of mice. All values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05. (E,F) Representative scanning EM analysis of Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− epididymal cauda sperm. Insert (F) is the higher magnification image of the head and neck region of the sperm. Scale bars: 5 μm; insert: 1 μm. (G,H) Representative TEM analysis of Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− epididymal cauda sperm. Scale bars: 500 nm.

Representative TEM images of corpus epididymal sperm from Ncoa5+/+Il-6+/+, Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/+ and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice. (A) TEM of Ncoa5+/+Il-6+/+ corpus epididymal sperm. Blue arrows indicate the normal morphology of the cytoplasmic droplet. (B) TEM of Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/+ corpus epididymal sperm. Red arrows indicate the abnormal morphology of sperm with the head wrapped around by the tail. (C) TEM of Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− corpus epididymal sperm. The presence of both blue (normal) and red (abnormal) arrows indicates the number of normal sperm increases in Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− male mice. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Discussion

Genetic abnormalities and/or inflammation in male reproductive organs including epididymitis, orchitis, prostatitis, varicocoele, and testicular torsion as well as drug therapy and lifestyle choices have been known to cause male infertility in human. Nonetheless, it has been reported that 30–75% of infertile male patients are idiopathic23,24,25. It is generally believed that novel inherited and/or acquired mutations in genes involved in spermatogenesis could be the etiological factors in these cases. However, identification of novel inherited genetic abnormalities has been limited because the penetration of such mutations into populations is relatively rare. Herein, using a genetically-engineered mouse model of heterozygous Ncoa5 deletion, we demonstrated that NCOA5 plays an essential role in male fertility, at least in part through the regulation of IL-6 expression in epididymis. Our results suggest a critical role of NCOA5 in epididymal sperm maturation and further implicate NCOA5 deficiency as a possible etiological risk in human male infertility.

A number of previous studies have indicated roles of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 in male reproductive function14. Although the immune system may be the major source of these cytokines, other cells in the reproductive tract such as epididymal epithelial cells and spermatozoa may also secrete cytokines. Existing evidence has implicated that cytokines including IL-6 can modulate and influence sperm activity and male fertility, as the IL-6 concentration in seminal plasma of infertile men was found to be significantly higher than that of fertile men26. Moreover, it was reported that higher level of IL-6 in seminal plasma was negatively correlated with spermatozoa vitality and motility in men27. NCOA5 was previously shown to be assembled on the promoter of IL-6 gene and negatively regulate its transcription in hepatic macrophages and heterozygous deletion of Ncoa5 resulted in increased IL-6 expression in the livers of male mice21. Thus, it is possible that NCOA5 may also play an inhibitory role in the regulation of IL-6 expression in epididymal epithelial cells and its inhibition may result in elevated expression of IL-6 in mouse epididymis. In agreement with the previous observations, we showed that IL-6 expression was elevated in the epididymis of Ncoa5+/− male mice. Concomitantly, the motility, progression and morphology of the sperm in Ncoa5+/− epididymis appeared abnormal. Significantly, we demonstrated for the first time that heterozygous deletion of Il-6, partially rescued male mouse infertility phenotype through improving sperm morphology and increasing the sperm motility and progression. This provides in vivo evidence to reinforce a causative role of IL-6 overexpression in male infertility. Given the fact that the development of sperm motility and maturation is completed through progressive steps in epididymis6 and IL-6 could impact on cell differentiation through the SOCS3/STAT3 signaling pathway28, we postulate that elevated IL-6 may contribute to sperm malfunction and infertility of Ncoa5+/− male mice through impairing sperm motility and quality. However, it remains to be determined how increased IL-6 expression in epididymis affects development of sperm motility and maturation.

While resulting in this partial improvement of fertility phenotypes, heterozygous deletion of Il-6 gene was, however, incapable of increasing the activity of Ncoa5+/− sperm to the levels comparable to those of WT sperm, suggesting that additional pathogenic effects caused by NCOA5 deficiency may contribute to the development of abnormal sperm in Ncoa5+/− male mice. Since Ncoa5+/− livers in male mice exhibited chronic inflammation with increased macrophage infiltration and expression of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α21, it is possible that Ncoa5+/− epididymis may also develop chronic inflammation with increased expression of multiple inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, we do not rule out the possibility that other cytokines expressed in Ncoa5+/− epididymis may also affect the development of sperm in Ncoa5+/− male mice. Given the role of NCOA5 in ERα-mediated transcription18,19, NCOA5 deficiency might possibly influence expression of other genes regulated by ERα, contributing to the development of infertility. Indeed, significantly reduced levels of proteins such as the sodium/hydrogen exchanger SLC9A3, sodium/bicarbonate cotransporter SLC4A4 and CAR14 in the initial segment of epididymis were observed in ERα knockout (Esr1KO) mice29,30,31. Esr1KO mice are infertile due to significantly reduced sperm motility and progressive motility as well as morphological changes of sperm29. Thus, further research is needed to explore whether reduced expression of these three proteins occurs in Ncoa5+/− epididymis and also accounts for infertility of Ncoa5+/− male mice.

In summary, we have demonstrated that heterozygous deletion of Ncoa5 resulted in decreased sperm motility and progression and severely impaired fertility in male mice, which were partially rescued by heterozygous deletion of Il-6 gene. These results suggest NCOA5 as a critical regulator that controls epididymal sperm maturation through regulates IL-6 expression in the epididymis. Our findings not only offer a molecular mechanism underlying male infertility, but also provide a specific target for development of novel therapeutic approaches for human male infertility.

Materials and Methods

Mouse mating and reproduction for determination of fertility

Detailed information of generation of Ncoa5+/− and Ncoa5+/−Il-6+/− mice was described in a previous publication21. All mice were housed in microisolator cages at Michigan State University animal facility. To determine the fertility of male mice, 2-month-old male mouse was housed with age-matched female mouse as monogamous pair and monitored for pup birth for 6 months. Pups in each litter were counted and weaned by 21 days. All experimental procedures on mice were in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Morphologic analysis

Histological analyses of mouse testis and epididymis were carried out as described previously21. Briefly, tissues were dissected and fixed in 10% formalin solution. Fixed tissues were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned and H & E stained by the Histopathology laboratory at Michigan State University. H & E staining was examined under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse E600) by S.G, H.X., and G.I.P who is a certified veterinarian with extensive experience in mouse reproduction research. For the examination of epididymal sperm, cauda epididymides were collected in M2 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) and immediately transferred into HTF medium (Human Tubal Fluid, EMD Millipore, MA, USA) followed by incubating at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 1 hour. An aliquot of sperm suspension (10 µl) was fixed and examined under a phase contrast microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-U inverted microscope).

Cauda epididymal sperm analysis

Cauda epididymides were harvested from male mice and washed once in M2 medium. Microdrops of HTF medium were prepared at least four hours before, covered with light mineral oil (Chemicon, MilliporeSigma, MA, USA) and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Cauda epididymides were placed individually to microdrops of equilibrated HTF medium, and the sperm was released by gently puncturing the epididymides with a needle under a dissecting scope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-U inverted microscope). Sperm were then capacitated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 1 hour. Capacitated sperm were mixed with M2 medium for a dilution (1:20), 10 µl of sperm were then added to a slide and analyzed under the Integrated Visual Optical System (IVOS, Hamilton Thorne, Inc, Beverly, MA, USA). About 200 sperm were counted. The concentration, motility and progression of each sperm sample were collected from the IVOS software. Sperm that are highly motile with progressive motility or move fast and progressively are counted as motile or progressively motile respectively.

Ultrastructural analyses

TEM and SEM analyses were performed according to previously described methods32 with minor changes. Specifically, for TEM, the concentration of paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde used in our protocol was 2.5%. For dehydration, the blocks were washed with 30%, 50%, 70%, 95% and 100% acetone for 10 min at each concentration. For SEM, CPD 030 Critical Point Dryer (Bal-TEC AG, FL, USA) was used. The EMSCOPE SC500 Sputter coater (Ashford, Kent, Great Britain) was used to coat the sample. Transmitting electron microscope (JEOL100 CXII, JEOL USA, Inc, MA, USA) and scanning electron microscope (JEOL 6610LV, JEOL USA, Inc, MA, USA) were utilized for the electron microscopic analyses and the morphometric images were analyzed by S.G and G.I.P.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Mouse tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, sectioned in the Histopathology laboratory at Michigan State University. IHC analyses of IL-6 were performed according to the protocol supplied by Cell Signaling Technology (CA, USA).

Western-blot analysis

Mice were euthanized and then epididymides were harvested and homogenized. Whole protein lysates were subjected to Western-Blot analysis. Western blots were performed and developed by Odyssey infrared scanner according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Li-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) as described previously33. Briefly, fluorescent intensity of bands was determined using Odyssey Infrared Imagine System Application Software v3.0, and the expression level for protein of interest was calculated as the ratio of fluorescent intensity between protein of interest and endogenous control protein. NCOA5 (A300–790A 1:1000 dilution), IL-6 (SC-1265, 1:500 dilution) or β-actin (SC-47778, 1:1000 dilution) antibodies were purchased from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX, USA) or Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), respectively. For the control experiment shown in Fig. S4C conducted to confirm the specificity of secondary antibodies, the membrane was firstly stripped with Li-COR NewBlot PVDF Stripping Buffer according to manufacturer’s protocols.

Statistical analysis

The differences between groups were analyzed using unpaired Student’s 2-tailed t test or two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. n = the number of mice per group. Values are expressed as Mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

References

Agarwal, A., Mulgund, A., Hamada, A. & Chyatte, M. R. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 13, 37 (2015).

Ogawa, S. et al. Abolition of male sexual behaviors in mice lacking estrogen receptors alpha and beta (alpha beta ERKO). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97, 14737–14741 (2000).

Pang, X. H. et al. Preoperative levels of serum interleukin-6 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 58, 1687–1693 (2011).

Xu, B., Washington, A. M. & Hinton, B. T. PTEN signaling through RAF1 proto-oncogene serine/threonine kinase (RAF1)/ERK in the epididymis is essential for male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 18643–18648 (2014).

Borg, C. L., Wolski, K. M., Gibbs, G. M. & O’Bryan, M. K. Phenotyping male infertility in the mouse: how to get the most out of a ‘non-performer’. Hum Reprod Update 16, 205–224 (2010).

Dacheux, J. L. & Dacheux, F. New insights into epididymal function in relation to sperm maturation. Reproduction 147, R27–42 (2014).

Choy, J. T. & Eisenberg, M. L. Male infertility as a window to health. Fertil Steril 110, 810–814 (2018).

Kasturi, S. S., Tannir, J. & Brannigan, R. E. The metabolic syndrome and male infertility. J Androl 29, 251–259 (2008).

Franze, K. et al. Neurite branch retraction is caused by a threshold-dependent mechanical impact. Biophys J 97, 1883–1890 (2009).

Haidl, G., Allam, J. P. & Schuppe, H. C. Chronic epididymitis: impact on semen parameters and therapeutic options. Andrologia 40, 92–96 (2008).

Wolf, J., Rose-John, S. & Garbers, C. Interleukin-6 and its receptors: a highly regulated and dynamic system. Cytokine 70, 11–20 (2014).

Hibi, M. et al. Molecular cloning and expression of an IL-6 signal transducer, gp130. Cell 63, 1149–1157 (1990).

Potashnik, H. et al. Interleukin-6 expression during normal maturation of the mouse testis. Eur Cytokine Netw 16, 161–165 (2005).

Lampiao, F. & du Plessis, S. S. TNF-alpha and IL-6 affect human sperm function by elevating nitric oxide production. Reprod Biomed Online 17, 628–631 (2008).

Hakovirta, H., Syed, V., Jegou, B. & Parvinen, M. Function of interleukin-6 as an inhibitor of meiotic DNA synthesis in the rat seminiferous epithelium. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 108, 193–198 (1995).

Nallella, K. P. et al. Relationship of interleukin-6 with semen characteristics and oxidative stress in patients with varicocele. Urology 64, 1010–1013 (2004).

Matalliotakis, I. et al. Interleukin-6 in seminal plasma of fertile and infertile men. Arch Androl 41, 43–50 (1998).

Sauve, F. et al. CIA, a novel estrogen receptor coactivator with a bifunctional nuclear receptor interacting determinant. Mol Cell Biol 21, 343–353 (2001).

Jiang, C. et al. TIP30 interacts with an estrogen receptor alpha-interacting coactivator CIA and regulates c-myc transcription. J Biol Chem 279, 27781–27789 (2004).

Gillespie, M. A. et al. An LXR-NCOA5 gene regulatory complex directs inflammatory crosstalk-dependent repression of macrophage cholesterol efflux. EMBO J 34, 1244–1258 (2015).

Gao, S. et al. NCOA5 haploinsufficiency results in glucose intolerance and subsequent hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 24, 725–737 (2013).

Dhar, D., Seki, E. & Karin, M. NCOA5, IL-6, type 2 diabetes, and HCC: The deadly quartet. Cell Metab 19, 6–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.010 (2014).

Ferlin, A., Arredi, B. & Foresta, C. Genetic causes of male infertility. Reprod Toxicol 22, 133–141 (2006).

Kothandaraman, N., Agarwal, A., Abu-Elmagd, M. & Al-Qahtani, M. H. Pathogenic landscape of idiopathic male infertility: new insight towards its regulatory networks. NPJ Genom Med 1, 16023, https://doi.org/10.1038/npjgenmed.2016.23 (2016).

Fainberg, J. & Kashanian, J. A. Recent advances in understanding and managing male infertility. F1000Res 8, doi:F1000 Faculty Rev-670 (2019).

Camejo, M. I., Segnini, A. & Proverbio, F. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) in seminal plasma of infertile men, and lipid peroxidation of their sperm. Arch Androl 47, 97–101 (2001).

Duan, Y. G. et al. Dendritic cells in semen of infertile men: association with sperm quality and inflammatory status of the epididymis. Fertil Steril 101, 70–77 (2014).

Huang, G. et al. IL-6 mediates differentiation disorder during spermatogenesis in obesity-associated inflammation by affecting the expression of Zfp637 through the SOCS3/STAT3 pathway. Sci Rep 6, 28012 (2016).

Joseph, A. et al. Absence of estrogen receptor alpha leads to physiological alterations in the mouse epididymis and consequent defects in sperm function. Biol Reprod 82, 948–957 (2010).

Joseph, A., Shur, B. D., Ko, C., Chambon, P. & Hess, R. A. Epididymal hypo-osmolality induces abnormal sperm morphology and function in the estrogen receptor alpha knockout mouse. Biol Reprod 82, 958–967 (2010).

Joseph, A., Shur, B. D. & Hess, R. A. Estrogen, efferent ductules, and the epididymis. Biol Reprod 84, 207–217 (2011).

Zheng, H. et al. Lack of Spem1 causes aberrant cytoplasm removal, sperm deformation, and male infertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 6852–6857 (2007).

Li, A. et al. TIP30 loss enhances cytoplasmic and nuclear EGFR signaling and promotes lung adenocarcinogenesis in mice. Oncogene 32, 2273–2281 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Chen Chen for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the Center for Advanced Microscopy, Michigan State University and Andalucian Laboratory of Cellular Reprogramming, Seville, Spain for their help in ultrastructure analysis. This work was supported by the NIH grant (R01CA188305) and the NIH grant (R21CA185021) to H. X. Y. Z. was supported by the Continuation Fellowship award from Michigan State University, and the Aitch Fellowship award from the Aitch Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. and G.P. performed, analyzed and designed all experiments, and prepared Figs 1–6, Y.Z. performed experiments in Fig. 4A,B. C.Y. and H.X. analyzed and interpreted data. S. G. and H.X. wrote the paper. C.Y. and G.P. edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, S., Zhang, Y., Yang, C. et al. NCOA5 Haplo-insufficiency Results in Male Mouse Infertility through Increased IL-6 Expression in the Epididymis. Sci Rep 9, 15525 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52105-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52105-9

This article is cited by

-

Could NCOA5 a novel candidate gene for multiple sclerosis susceptibility?

Molecular Biology Reports (2023)

-

Recent advances in anti-inflammatory active components and action mechanisms of natural medicines

Inflammopharmacology (2023)

-

Interleukin-6 deficiency modulates testicular function by increasing the expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) in mice

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Sperm biology and male reproductive health

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.