Abstract

Seawater pH is undergoing a decreasing trend due to the absorption of atmospheric CO2, a phenomenon known as ocean acidification (OA). Biogeochemical processes occurring naturally in the ocean also change pH and hence, for an accurate assessment of OA, the contribution of the natural component to the total pH variation must be quantified. In this work, we used 11 years (2005–2015) of biogeochemical measurements collected at the Strait of Gibraltar to estimate decadal trends of pH in two major Mediterranean water masses, the Western Mediterranean Deep Water (WMDW) and the Levantine Intermediate Water (LIW) and assess the magnitude of natural and anthropogenic components on the total pH change. The assessment was also performed in the North Atlantic Central Water (NACW) feeding the Mediterranean Sea. Our analysis revealed a significant human impact on all water masses in terms of accumulation of anthropogenic CO2. However, the decadal pH decline found in the WMDW and the NACW was markedly affected by natural processes, which accounted for by nearly 60% and 40% of the total pH decrease, respectively. The LIW did not exhibit a significant pH temporal trend although data indicated natural and anthropogenic perturbations on its biogeochemical signatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) has markedly increased from the beginning of the industrial era due to the release of carbon from combustion of fossil fuels, deforestation and large changes in land-use activities. Anthropogenic emissions in particular, became the dominant source of CO2 to the atmosphere around the mid XX century and continue rising at present1. The global ocean plays a relevant role mitigating this rise through the absorption of around a quarter of the emissions1. Recently, the oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 (CANT) over the period 1994–2007 has been estimated to represent 31% of the global emissions2. Hence, the oceanic withdrawal of atmospheric CO2 alleviates the greenhouse effect, but there is also a downside, as the CO2 absorbed by the ocean changes the chemistry of seawater by lowering its pH and the carbonate ion (CO23−) levels. The chemical reactions derived from the uptake of CO2 are generally termed ocean acidification3 and threaten the overall structure of marine ecosystems at a planetary scale4.

Ocean acidification trends have been already documented through multi-decadal measurements in open ocean marine observatories5. It has been also suggested that certain basins, such as marginal seas, will be more impacted by the phenomenon than others6. This is the case of the Mediterranean Sea (MedSea), whose high sensitivity to acidification has been attributed to particular biogeochemical features and water circulation patterns7,8. The high alkalinity of Mediterranean waters and an active overturning circulation result in both an increased absorption of atmospheric CO2 and an intensified carbon transport from the surface to the ocean interior6,9,10. Moreover, CANT is imported continuously from the North Atlantic through the Strait of Gibraltar (SoG, Fig. 1A)10,11, leading to its accumulation in the basin at a long term.

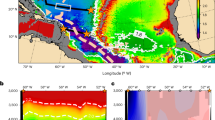

Study area. (A) Location of the Strait of Gibraltar, Gulf of Cadiz (GC) and Alboran Sea (AS); (B) Position of GIFT stations (G1, G2 and G3), Camarinal sill (CS) and Espartel sill (ES). Bathymetry (m) in the channel is indicated with the color contour; (C) Spatial distribution of salinity based on archetypal values. AI and MOW stand for Atlantic inflow and Mediterranean Outflow Water respectively. Ocean Data View software (Schlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, odv.awi.de, 2018) was used to display data.

The MedSea is indeed experiencing a decrease in pH although different declining rates have been reported9,10,12,13,14. Some works have provided a total pH decline between −0.055 and −0.156 pH units9,12 whereas other studies reported values ranging from −0.005 to −0.06 pH10,13. These discrepancies are based on the simulation of the quantity of CANT that is taken up by Mediterranean water masses. This amount cannot be measured directly because it cannot be distinguished from the much larger natural carbon background and it has to be calculated through indirect approaches. The estimation of CANT using methods that combine observable physical and biogeochemical variables or models result then in different acidification rates.

However, seawater pH also varies “naturally” as a consequence of physical and biological processes, such as ocean circulation mechanisms and/or changes in ecosystem metabolism15,16,17. In fact, the pH decline due to biology in Atlantic water masses is of the same order of magnitude than the pH decrease caused by CANT absorption15. Similarly, in the Northeast Pacific coastal ocean, long-term ocean acidification is modulated by the pH variability driven by ecosystem metabolism17. Hence, the accurate assessment of the actual extent of ocean acidification requires the identification of the fraction of the total pH change that is purely due to natural processes and discriminate it from the anthropogenic fraction. This analysis is particularly relevant in the MedSea where biogeochemistry is closely linked to water circulation patterns18,19.

In the current study we examined the relative contribution of both CANT uptake and biology on temporal pH trends in two major Mediterranean water masses, the Western Mediterranean Deep Water (WMDW) and the Levantine Intermediate Water (LIW). They are originated in distant regions, such as the Gulf of Lions located in the Western Mediterranean and the Levantine basin in the Eastern Mediterranean, respectively. Nevertheless, both water masses can be easily tracked in the SoG by their characteristic thermohaline signatures13,20.

More specifically, ocean circulation in the MedSea starts with the entry of surface water from the Atlantic Ocean through the SoG, which flows towards the east while gaining salinity and density. In the Levantine basin the density has reached such an extent that the water sinks to form the LIW, which flows back into the opposite direction in a few 100 m depth. In the Gulf of Lions, high salinity waters cool down regularly in winter reaching enhanced densities and forming the WMDW, with the highly saline LIW acting as a preconditioner for deep water formation21,22. Both water masses leave jointly the MedSea as part of a dense (salinity >38) Mediterranean Outflow Water (MOW) that occupies the bottom layer in the SoG (Fig. 1C). The MOW is compensated by the surface eastward warmer (and less salty) Atlantic Inflow (AI, Fig. 1C) that is mainly constituted by the North Atlantic Central Water (NACW). The MOW and AI are clearly distinguishable within the channel by their different physical and biogeochemical properties, such as potential temperature, salinity, alkalinity, dissolved oxygen, inorganic nutrients and trace gases, as shown by measurements at the Gibraltar Fixed Time series (GIFT, Fig. 1B)11,23,24.

Here, we present the first (to our knowledge) measurement-based temporal evolution of the carbon system parameters in water masses exchanging through the SoG using observations collected between the years 2005–2015, with special emphasis in decadal trends of pH. The anthropogenic (pHnobio) and natural (pHbio) components of the decadal pH change were subsequently obtained in order to identify the relative contribution of both drivers on the pH variability observed in each water mass.

Materials and Methods

Dataset

Data were collected periodically at three stations that form the GIFT time series, G1 (5°58.60W, 35°51.68N), G2 (5°44.75W, 35°54.71N) and G3 (5°22.10W, 35°59.19N) (Fig. 1B), during 26 campaigns conducted over the decade 2005–2015 (Table 1). In 8 cruises (denoted as CARBOGIB in Table 1), 4 more stations of a North-South grid perpendicular to the GIFT section were sampled, (5°44.04W, 35°52.67N), (5°44.36W, 35°53.50N), (5°45.33W, 35°56.56N) and (5°45.56W, 35°58.53N). Even though several analysis have allowed to conclude that monitoring at the GIFT is effective to fully resolve the vertical and horizontal structure of the water column in the area11,23,24, data acquired in the perpendicular leg have been also included in our assessment (Table 1). A total of 5,145 measurements have been used.

Data acquisition procedure was identical for all campaigns. A temperature and salinity profile was obtained with a Seabird 911Plus CTD probe. Seawater was subsequently collected for biogeochemical analysis using Niskin bottles immersed in an oceanographic rosette platform at variable depths (from 5 to 8 levels) depending on the instant position of the interface between the AI and MOW that was identified by the CTD profiles

Biogeochemical analysis

The biogeochemical variables considered in this study have been pH in total scale at 25 °C (pHT25), total alkalinity (AT), Dissolved Oxygen (DO) and inorganic nutrients (phosphate, PO43−, nitrate, NO3− and Silicate, SiO44−).

pHT25 data were obtained by the spectrophotometric method with m-cresol purple as indicator25. Samples were taken directly from the oceanographic bottles in 10 cm path-length optical glass cells and measurements were carried out with a Shimadzu UV-2401PC spectrophotometer containing a 25 °C-thermostated cells holder11. Precision and accuracy of the pH measurements were ± 0.0052 and ± 0.0055 respectively, which were determined from measurements of certified reference material (CRM batches#94, #97 and #136 provided by Prof. Andrew Dickson, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, CA, USA).

For further analysis of the influence of the age of water masses on the pH evolution, the theoretical seawater pH values that would result exclusively from the uptake of atmospheric CO2 were also calculated with the CO2SYS program26 using temperature, pressure, AT, pHT25 and inorganic nutrients as inputs parameters. Atmospheric CO2 levels were taken from the Izaña Observatory (Meteorological State Agency of Spain, AEMET, https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/)

Samples for AT analysis were collected in 500-ml borosilicate bottles, and poisoned with 100 μl of HgCl2-saturated aqueous solution and stored until measurement in the laboratory. AT was measured by potential titration27 with a Titroprocessor (model Metrohm 794). Precision and accuracy of AT measurements were ±0.9 and ±5.4 μmol kg−1 respectively, which were determined from measurements of 54 CRMs of the above mentioned batches.

Concentration of dissolved inorganic carbon c(DIC) and partial pressure of dissolved CO2 (pCO2) were calculated using CO2SYS with the dissociation constants for carbon28,29 and sulphate30.

DO concentration [c(DO)] was determined through automated potentiometric modification of the original Winkler method using the Titroprocessor. Upon collection, flasks were sealed, stored in darkness and measured within 24 h. The error of measurements was ±2 μmol kg−1 (n = 115). Apparent Oxygen Utilization (AOU) values were calculated with the solubility equation31.

Water samples (5 mL, two replicates) for inorganic nutrients determination were taken, filtered immediately (Whatman GF/F, 0.7 μm) and stored frozen32 for later analyses in the shore-based laboratory. Nutrients concentrations were measured with a continuous flow auto-analyzer (SkalarSan ++215) using standard colorimetric techniques33. Analytical precisions were always better than ±3%.

Anthropogenic carbon estimation

CANT concentration was estimated using the back-calculation technique34 by applying the following equation:

where the stoichiometric coefficients RC (−ΔO2/ΔC) = 1.45 and RN (−ΔO2/ΔN)=10.6 were used35. c(AOU)/RC corresponds to the DIC increase due to organic matter oxidation, 1/2(ΔAT + c(AOU)/RN) accounts for the DIC change due to CaCO3 dissolution–precipitation and ΔAT = AT − AT° is the total alkalinity variation since the water mass was formed. Preformed alkalinity (AT°) and the disequilibrium term that stands for the air–sea CO2 difference (ΔCdis) were calculated for each water sample from the mixing proportion of the different water masses. This was carried out by an extended optimum multiparameter analysis (eOMP)36,37. The AT° type values for the NACW were calculated using the approach proposed by38 while those proposed by39 and40 were used in the case of the MOW, by considering existing CFC and CO2 exchange data from the Mediterranean basin, following a previous study37. C°T278 represents the c(DIC) in equilibrium with the preindustrial atmospheric CO2 molar fraction of 278 ppm and was calculated with the proper dissociation constants28,29,30. (ΔCdis) for both NACW and MOW were considered to be −12 ± 5 μmol kg−1 and 0 ± 5 μmol kg−1, respectively11,41. Uncertainty associated to CANT calculation was estimated through an error propagation analysis, resulting in ±5.0 μmol kg−1.

An additional OMP analysis was performed to resolve the water masses structure within the MOW and obtain biogeochemical parameters in the LIW and the WMDW. Potential temperature and salinity chosen as end members for water masses characterization were 13.22, 12.8 °C and 38.56, 38.45 for the LIW and the WMDW respectively13.

Calculation of archetypal concentrations

In order to evaluate the decadal variation of pHT25, CANT, c(AOU), c(DIC) and pCO2 in water masses at the SoG, annual archetypal concentrations were calculated, which correspond to the mixing-weighted average concentrations of a single parameter in a particular water mass42. The archetypal concentrations of a parameter N in a water mass i can be obtained by the equation:

where Nj is the concentration of N in sample j, and xij is the fraction of the water mass i in the sample j. Here, xij of each water mass present in the SoG was obtained by the OMP analysis. Standard deviation (SD) of archetypal concentrations was calculated through the formula:

Anthropogenic and natural components of pH change

The contribution of anthropogenic and natural drivers affecting total pH variation in each water mass was estimated by calculating the effect of non-biological processes on pHT25 changes (pHnobio), extracting the biological contribution as follows:

where \({r}_{{O}_{2}:{C}_{org}}\) is the stoichiometric ratio35 and ΔpH was given an annual average constant value of 0.0025, assuming that surface seawater is in equilibrium with the global mean rate of atmospheric CO2 increase.

Determination of temporal trends and Statistics

Considering the annual archetypal concentrations of each parameter during the 11 years period, annual variation trends were determined by ordinary linear regression and standard errors and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the slopes of the regressions.

Results

Biogeochemistry in waters of the SoG: decadal spatial distribution

Water circulation in the SoG is illustrated in Fig. 2(A–C) where the decadal averaged proportions of the water masses exchanging through the channel have been plotted. The eastward Atlantic inflow (represented here by the fraction of the NACW) invariable occupied the upper layer whereas Mediterranean waters (LIW and WMDW) flew towards the west in depth (Fig. 2A–C). However, the depth and thickness of each water mass varied along the Strait, which is due to the influence of physical mechanisms that act at different temporal scales, such as tidal currents, winds, atmospheric pressure variations and circulation processes forced by bathymetry that ultimately determine the vertical position of water masses20. Thus, the NACW moves upwards toward the easternmost part of the channel, shifting from 200 m at station G1 to around 70 m at station G3 (Fig. 2A). Worth mentioning is the remarkable variability in water types proportion between the Espartel sill (358 m depth) and the Camarinal sill (285 m depth) (ES and CS in Fig. 1B), which is the consequence of the enhanced mixing and turbulence related to the internal hydraulic jump formed during most tidal cycles downstream of Camarinal43,44,45. Moreover, the Atlantic water accelerates in the CS (station G2) and entrains the Mediterranean layer43, which results in appreciable changes in the water masses proportion around this area that can be effectively resolved by the OMP analysis (Fig. 2A–C). Even though horizontal variations in the vertical position of the LIW and the WMDW can be also observed along the channel in response to hydrodynamic features, the former was present at intermediate depths and the latter occupied the bottom layer, which is particularly clear at station G3 (Fig. 2B,C).

Water masses and biogeochemistry in the Strait of Gibraltar. Fraction (%) of the different water masses present in the area (panels A–C) and spatial distribution of decadal averaged concentrations of (D) c(DIC) (μmol kg−1); (E) AT (μmol kg−1); (F) c(AOU) (μmol kg−1); (G) pHT25; (H) pCO2 (μatm) and (I) CANT (μmol kg−1). NACW, LIW and WMDW correspond to North Atlantic central Water, Levantine Intermediate Water and Western Mediterranean Deep Water, respectively. Ocean Data View software (Schlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, odv.awi.de, 2018) was used to display data.

Water masses allocation in the SoG clearly conditions the spatial distribution of the carbon system parameters within the channel, as shown by the vertical gradients of the decadal averaged concentrations (Fig. 2D–I)

The NACW exhibited the lowest averaged c(DIC) and a marked vertical variability (Fig. 2D), with a mean value of 2127 ± 33 μmol kg−1. In contrast, the LIW and the WMDW were characterized by higher and similar mean decadal DIC levels, equivalent to 2322.6 ± 12.7 μmol kg−1 and 2311.7 ± 18.8 μmol kg−1 respectively (Fig. 2D), which match previous discrete measurements reported in different regions of the Mediterranean basin7,9.

AT also increased gradually with depth (Fig. 2E), with lower decadal averaged concentrations being found in the upper NACW (2310 ± 22 μmol kg−1) in relation to those in the LIW and WMDW (2570 ± 14 and 2567 ± 21 μmol kg−1, respectively). The similar pattern followed by AT and c(DIC) with salinity (Figs 1C and 2D,E) is in agreement with the conservative behaviour of these parameters described in the past11,40.

In contrast, pHT25 decreased within the water column (Fig. 2G), and decadal averaged pHT25 values were 7.950 ± 0.043, 7.877 ± 0.015 and 7.891 ± 0.011 in the NACW, LIW and WMDW respectively (Fig. 2G). The mean values obtained in the Mediterranean water masses coincide with earlier observations in the SoG13 and Western Mediterranean7 whereas the higher pH variability observed in the NACW has been associated to the influence of biology into the photic zone and changes in evaporation and mixing46.

As expected according to the pHT25 distribution, pCO2 levels increased in the LIW (Fig. 2H) with respect to the rest of water masses, with decadal averaged pCO2 values being 430 ± 17, 407 ± 13 and 376 ± 30 µatm in the LIW, WMDW and NACW respectively. During the monitoring period, surface Atlantic waters were hence undersaturated with respect to atmospheric CO2 levels, which gradually rose from 379.8 µatm in 2005 to 400.8 µatm in 2015.

The relatively low pHT25 values characterizing Mediterranean waters are taken as an indication of the active organic matter remineralization occurring in the basin47. Our AOU data suggest indeed a remarkable oxidation of organic compounds in Mediterranean water masses, as decadal averaged AOU levels were 65 ± 14 μmol kg−1 in the LIW and 66 ± 7 μmol kg−1 in the WMDW (Fig. 2F). In the case of the NACW, a decadal AOU concentration of 12 ± 22 μmol kg−1 was obtained.

CANT distribution in the SoG (Fig. 2I) was also influenced by the pattern of water exchange and circulation. The highest CANT concentrations were attained in the NACW, particularly in the first 100 m depth at the westernmost side of the channel where mixing with the MOW is insignificant (Fig. 2A). Decadal averaged CANT concentrations were 75 ± 16, 71 ± 11 and 52 ± 8 µmol kg−1 in the NACW, WMDW and LIW respectively.

It is worth noting the appreciable changes in the vertical profiles of the carbon system parameters westwards of station G2 (Fig. 2D–I), which can be attributed to variation in the water masses proportion brought about by the energetic hydrodynamic feature caused the tidal cycle in the CS area (Fig. 2A–C).

Archetypal concentrations trends

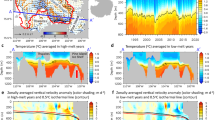

The temporal evolution of archetypal concentrations of the carbon system parameters in the NACW revealed a clear decadal trend (Fig. 3). In particular, pHT25 in this water mass showed a marked decrease over the decade 2005–2015 (Fig. 3A), at an annual rate of −0.0036 ± 0.0005 a−1 (Table 2). Moreover, AOU and DIC concentrations in Atlantic waters increased annually during the period of study (Fig. 3B,C), at rates of 1.1 ± 0.4 and 3.5 ± 0.6 µmol kg−1 a−1, respectively (Table 2). Similarly, CANT concentration in the NACW also rose gradually with time, at an annual rate of 1.5 ± 0.6 µmol kg−1.

Decadal trends of carbon system parameters in water masses of the Strait of Gibraltar. Annual archetypal concentrations of (A) pHT25, (B) c(DIC) (μmol kg−1), (C) c(AOU) (μmol kg−1) and (D) CANT (μmol kg−1) during the 2005–2015 decade in the NACW (blue), LIW (red) and WMDW (grey). Error bars correspond to the standard deviation (SD) of archetypal concentrations of each parameter in all water masses, which were calculated through Eq. 3.

Archetypal concentrations of pHT25, AOU and DIC in the LIW were quite stable during the monitoring period and a clear decadal tendency was not observed in any case (Fig. 3). In fact, c(AOU) and c(DIC) presented the highest annual archetypal levels in relation to those found in the rest of water masses but with negligible annual variation rates (Table 2). On the other hand, a slight temporal increase in the levels of CANT could be detected in the LIW, at a rate of 0.3 ± 0.7 µmol kg−1 a−1.

In contrast, the WMDW exhibited a noticeable acidification trend over the 2005–2015 decade (Fig. 3A), with pHT25 decreasing at a rate of −0.0009 ± 0.0005 a−1 (Table 2) although the significance of the statistics was weak. The gradual drop in pH was accompanied by increases in yearly archetypal concentrations of DIC (Fig. 3C) and CANT (Fig. 3D) at rates of 1.6 ± 1.5 µmol kg−1 a−1 and 0.9 ± 0.5 µmol kg−1 a−1, respectively (Table 2). The c(AOU) also rose during the decade (0.4 ± 0.5 µmol kg−1 a−1).

Annual archetypal concentrations of pCO2 were in opposition to the archetypal pHT25 levels observed in each water mass (not shown). The upper NACW that was characterized by the lowest decadal average pCO2 level (Fig. 2H) presented the highest pCO2 rise during the monitoring period, at a rate of 3.2 ± 0.9 µatm a−1 (Table 2). In the WMDW, pCO2 increased at a rate of 1.2 ± 0.7 µatm a−1 whereas the temporal evolution of pCO2 in the LIW was very smooth (Table 2).

The highest and lowest contribution of the anthropogenic component to the total pH decrease (\({\triangle {pH}}_{{\rm{nobio}}})\) was obtained in the NACW and the LIW, respectively (Table 2). In terms of percentage, the \({\triangle {pH}}_{{\rm{nobio}}}\) in the NACW had a weight of approximately 60% of the total annual decreasing pH rate and around 44% in the case of WMDW. Because of the negligible ΔpHT25 measured in the LIW, \({{pH}}_{{\rm{nobio}}}\) in this water mass did not provide any significant information.

Discussion

Data collected in the SoG during the 2005–2015 decade confirm previous findings indicating that water exchange in the region results in a CANT import from the Atlantic towards the Mediterranean basin10,11 as the NACW was always CANT enriched with respect to the MOW. Our periodic observations are also in agreement with the finding that the North Atlantic is the largest ocean sink for anthropogenic carbon2,48. The absorption of CANT by the NACW contributed to a noticeable decadal reduction of its pH, with the contribution of the anthropogenic component representing 60% of the total pH decline.

The rise in CANT content over time in the NACW spotted at the SoG occurred at a rate of 1.5 µmol kg−1 a−1 (Table 2), which matches quite well the decadal rate estimated previously in this water mass49. This increment in the quantity of anthropogenic carbon was accompanied by parallel increases in the concentration of DIC and AOU, also suggesting an enhanced organic matter oxidation during the 2005–2015 decade. Before crossing the Strait, the NACW transits through the Gulf of Cádiz (GC in Fig. 1A), a basin characterized by a high primary production50. Therefore, regional inputs of organic matter are likely to occur, which could well lead to an intensification in the ecosystem respiration and inorganic carbon accumulation with time. In addition, a considerable discharge of inorganic carbon from the Guadalquivir river estuary to the continental shelf of the GC has been measured51,52, which could be accounted as an extra DIC source for the NACW. These external inputs would contribute to the natural component affecting the decadal pH change in this water mass, which represented 40% of the total pH reduction. It is also worth noting that pCO2 in the NACW rose at a higher rate (3.2 ± 0.9) than the atmospheric CO2 annual trend (approximately 2 ppm)53. This divergence can be related to the air-sea CO2 disequilibrium driven by surface heat fluxes and the balance between the biological carbon uptake and CO2 outgassing46 that becomes larger with time54. Taking into account the atmospheric pCO2 levels during the monitoring period and an average 90% equilibrium with the anthropogenic fraction54, the theoretical pH values in the NACW that would result exclusively from atmospheric CO2 uptake were calculated and compared with the estimated \({{pH}}_{{nobio}}\) values. Comparison performed by a Mean Squared Error (MSE) revealed a difference of 0.0001 between both estimates and a mismatch between dissolved and atmospheric pCO2 concentrations equivalent to 8 years. This finding provides more evidence for local ecosystem drivers of pH fluctuations, as described elsewhere, particularly in coastal regions17,53.

Multi-decadal declines of pH in surface Atlantic waters have been observed in the open ocean5 yet few studies have quantified the relative importance of biological processes to modulate the pH change over time15. The acidification rate calculated here in the NACW from 2005 to 2015 (0.0036 pH a−1 Table 2) is of the same order of magnitude than others obtained in distant Atlantic basins although higher5 (e.g. 0.0026 and 0.0025 pH a−1 in the Irminger Sea and CARIACO basin, respectively). Interestingly, the rate of change of the anthropogenic component (pHnobio, 0.0021 pH a−1, Table 2) is quite similar to the total rates attained in the Atlantic time series where the rates of dissolved pCO2 rise resembled the current atmospheric CO2 increase5,53. The influence of regional biogeochemical processes on the carbon content of the NACW possibly amplified the temporal pH change and accounted for by the increased acidification trend found with our sustained observations, although this hypothesis remains to be tested.

On the other hand, the decadal rate of pH decrease in the WMDW is comparable to that reported for the Mediterranean finger print in the North Atlantic55,56 and lies between the limits established in Mediterranean bottom waters10. It can be argued that the pH tendency observed here is not fully supported by the regression statistics. However, it has been recognized that the statistical significance of seawater carbonate chemistry trends in time-series can be weak due to several reasons, such as the irregularity of sampling, non-uniform time intervals between cruises and seasonality in the measurements5,53. A further analysis conducted to remove seasonality and identify potential bias of sampling in our databse revealed no seasonal effect on the estimated trends (not shown).

Previous works have already concluded that the MedSea is experiencing an acidification process9,10,12,13,14,57 although the pattern of pH change is not uniform at a basin scale9,10, which can be attributable to both the west to east decreasing productivity gradient58 and water circulation mechanisms9,12.

Each winter, deep waters are formed in both the Eastern and Western Mediterranean. The recently formed waters mix with older and resident water masses, which change their chemical and physical properties; hence, it is not simple to anticipate the effect of water formation events on pH changes. In the particular case of the WMDW, several mechanisms impacting pH at distinct temporal scales must be taken into account, which ultimately complicates the identification of a significant temporal tendency. The WMDW is formed regularly by two processes, deep convection and dense shelf water cascading. The former induces direct downward transport of newly formed organic matter from the surface layer, which is enriched in labile and easily oxidizable material whose decomposition leads to significant CO2 release59,60. Hence, the WMDW receives a significant amount of pCO2 from organic matter degradation that is transported down during the formation event. Furthermore, the active ecosystem metabolism occurring in the Alboran sub-basin (AS in Fig. 1) where this water mass resides before leaving the basin61 is likely to increase its pCO2 bulk. In the Alboran Sea, a high primary production in the upper layer62 is coupled to a significant export to deep of organic material58 and a strong remineralization in the bottom layer59,63, which is indeed occupied by the WMDW61 (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the WMDW must gain a significant amount of pCO2 from natural processes before crossing the SoG. Both mechanisms, decomposition of labile organic matter at formation site and the cascading effect during residence time in the Alboran sub-basin would explain the strong biological component (around 60%) of the total pH decline found. The high AOU values measured in the WMDW here and concordant with previous measurements18 support this assumption.

Nevertheless, the process of the deep water mass formation in the Gulf of Lions is subject to a marked interannual variability, and thus, pH temporal evolution in the WMDW may not be regular, as evidenced in our time series. Our database identifies a clear pH decline during 2013 (Fig. 3A), which is also evident in the LIW. This particular year marks the occurrence of the Western Mediterranean Transition (WMT) at the SoG64. This phenomenon started with a strong WMDW production in the Gulf of Lions during the extreme cold winters of 2005 and 2006 that originated a remarkable deep convection. This deep water enriched in labile organic carbon18 arrived to the Alboran Sea and remained in the bottom layer. A subsequent cycle of deep convection during the harsh winters of 2012 and 2013 resulted in newly formed WMDW that was warmer, saltier and denser than the old one64 and caused its uplifting and propagation towards the Strait upon arrival in Alboran. The lower pH values observed in the WMDW in 2013 can be interpreted as the footprint of the older (and more acidified) fraction of this water mass after being almost entirely replaced by the more recent fraction. Moreover, it was inferred that the younger WMDW spilled over the SoG in 201564, which would explain the rise in pH observed in this water mass that year (Fig. 3A), corresponding to the signature of a less acidified fraction. The decrease observed in both CANT and c(AOU) in 2015 (Fig. 3B,D) is consistent with the presence of a water mass that was rapidly formed and sunk and remained in the AS a lower period of time. This interannual variability in the WMDW time series possibly blurs the identification of statistically significant long term tendencies. Changes in the proportion of fractions of WMDW carrying different levels of both natural and anthropogenic CO2 would also account for the discrepancy found between the acidification rate provided here and the one we observed previously in the SoG using three years (from 2012 to 2015) of continuous pH measurements within the MOW13. In fact, in the former study considering a shorter period of time, we reported a higher annual pH decline and drastic changes in the proportion of the WMDW during 3 years, which can be related to the influence of the WMT and the subsequent cycle of deep formation events. A thorough investigation of the hydrographic profiles available in our database would certainly contribute to unravel the observed pH variability in the WMDW and strengthen our conclusions but it is not the scope of the present study.

The WMT caused a near-complete renewal of the WMDW64 and possibly also some mixing with the LIW, thereby lowering its pH. Blurring of the LIW signal within the MOW has been identified in the SoG and diagnosed through salinity changes20, thus mixing between both water masses in the area is a common phenomenon.

Interestingly, during the monitoring period, the LIW exhibited similar pHT25 values than those in the WMDW although the temporal evolution of its pH was smoother, as observed in our earlier study13. The LIW originates in a distant sub-basin and crosses the entire Mediterranean basin before arriving at the SoG. Therefore, during transit, changes in pH, AOU and pCO2 are expected to proceed due to physical and biological processes. The LIW route from formation site is complicated as it follows different pathways65,66: first it moves westward from the Levantine basin forming two veins, one that flows to the Adriatic Sea and a second one that crosses the Strait of Sicily and enters in the Tyrrhenian. This vein eventually emerges from the Sardinian Channel, reaches the Ligurian Sea, the Gulf of Lions and finally flows towards the Algerian basin65. During this journey, changes in biogeochemical parameters, mainly dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and AOU, have been indeed found in response to the different trophic status of the sub-basins crossed18. In particular, the LIW passes by areas of strong organic matter remineralization that cause minimum contents of DOC and maximum levels of AOU18. The c(AOU) measured in the LIW during the 2005–2010 decade (within the range 60–70 µmol kg−1) are possibly the final result of all the biological changes experienced during transit, which modified original pH as well. Furthermore, as the LIW remains at intermediate depths in the SoG (Fig. 2B), Algerian and Alboran sub-basins61 the additional contribution of cascading processes to its pCO2 bulk cannot be totally neglected. Therefore, re-ventilation mechanisms suffered by the LIW, vertical transport of carbon by diffusion and mixing with the WMDW must alter its original biogeochemical characteristics and consequently lower its pH.

In fact, when the ages of the WMDW and the LIW are estimated, similar values are obtained and equivalent to 32 ± 8 and 34 ± 8 years, respectively (MSE < 0.0001). Alternatively, age calculation based on available CFC data39 yields estimates of 18 years for the WMDW and 21 years for the LIW. Although there is no consensus about the exact ages of Mediterranean water masses and discrepant values have been provided67,68, it is clear that our calculated ages for the LIW are lower than that expected for a water mass that has crossed the entire basin. Actually, the age of the LIW in the Western basin has been proposed to be in the range of 82–120 years67.

These findings and the fact that appreciable CANT levels were measured in the LIW support the occurrence of re-ventilaton and/or mixing with younger water masses. If we consider that the LIW currently spotted at the SoG corresponds to a water mass that sank originally in the Eastern basin and lost contact with the atmosphere roughly one century ago, it is plausible to assume that its CANT content would be negligible, as it was exposed to a very low atmospheric CO2 concentration upon formation (resembling the CO2 pre-industrial level). During transit, its position within the water column prevented any new contact with the atmosphere, thus hampering the absorption of the rising atmospheric CO2. Therefore, the LIW must gain anthropogenic carbon by other processes, and the most likely candidates are re-ventilation and mixing with more recently formed water masses, such as the Cretan Intermediate Water (CIW) in the Ionian Sea18 and the WMDW in the SoG20. This would alter the original biogeochemical characteristics of this water mass and in turn, estimations of its age and anthropogenic signals.

As the drivers of anthropogenic forcing and natural variability are not entirely constrained and their signals cannot be discerned at a statistically significant level, identification of acidification trend in the LIW would require a longer time period of periodic observations, as it has been recently shown in a number of time series53.

Conclusions

Our study evidences the presence of an anthropogenic impact on two major Mediterranean water masses, as appreciable CANT levels were measured in the WMWD and the LIW using 11 years of sustained observations at the Strait of Gibraltar. However, a clear acidification trend could only be identified in the former, with the contribution of the anthropogenic driver to the total pH change representing 40% of the decadal decline. As the LIW is an old water mass with no contact with the current atmosphere, its CANT content may be attributable to further contamination during transit across the basin from formation site. Longer monitoring period than that encompassed by our study and observations in the Eastern Mediterranean are required to detect long term pH variations in the LIW and constrains the relative importance of the natural and anthropogenic signals on its pH evolution.

It is plausible that the acidification phenomenon in the MedSea could be exacerbated in the future, as our assessment also shows that the incoming Atlantic water suffered a marked acidification trend over the decade. In this case, reduction in the pH of the NACW was dominated by the anthropogenic component, which accounted for by 60% of the total decrease. Regional biogeochemical processes might amplify natural pH variability in this water mass, resulting in higher acidification rates in relation to others observed in surface Atlantic waters.

Regardless of the relative contribution of the drivers affecting pH decline in Atlantic and Mediterranean waters, our findings are in support of the current concerns regarding the fate of marine ecosystems due to the increase in acidity of the seawater. Particularly, iconic habitats of cold water corals of the North Atlantic69 and Mediterranean Sea70 are expected to be highly impacted by the phenomenon, which is now corroborated by our assessment.

Hence, even though further work should be directed at improving upon our estimates by increasing the length of sustained observations, our decadal records still provide a starting point for future calculations of ocean acidification trends in Mediterranean waters and reveal the importance of long time series in this marginal sea.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Le Quéré, C. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 2141–2194 (2018).

Gruber, N. et al. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science 363(6432), 1193–1199 (2019).

Doney, S. C., Fabry, V. J., Feely, R. A. & Kleypas, J. A. Ocean Acidification: The Other CO2 Problem. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 1(1), 169–192 (2009).

IGBP, IOC, SCOR. Ocean Acidification Summary for Policymakers – Third Symposium on the Ocean in a High-CO2 World. International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, Stockholm, Sweden (2013).

Bates, N. R. et al. A time-series view of changing ocean chemistry due to ocean uptake of anthropogenic CO2 and ocean acidification. Oceanog. 27(1), 126–141 (2014).

Lee, K. et al. Roles of marginal seas in absorbing and storing fossil fuel CO2. Energy Environ. Sci. 4(4), 1133–1146 (2011).

Álvarez, M. et al. The CO2 system in the Mediterranean Sea: a basin wide perspective. Ocean Sci. 10(1), 69–92 (2014).

Hainbucher, D. et al. Hydrographic situation during M84/3 and P414. Ocean Sci. 10, 669–682 (2014).

Hassoun, A. E. R. et al. Acidification of the Mediterranean Sea from anthropogenic carbon penetration. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 102, 1–15 (2015).

Palmiéri, J. et al. Simulated anthropogenic CO2 storage and acidification of the Mediterranean Sea. Biogeosciences 12(3), 781–802 (2015).

Huertas, I. E. et al. Anthropogenic and natural CO2 exchange through the Strait of Gibraltar. Biogeosciences 6(4), 647–662 (2009).

Touratier, F. & Goyet, C. Impact of the Eastern Mediterranean Transient on the distribution of anthropogenic CO2 and first estimate of acidification for the Mediterranean Sea. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 58(1), 1–15 (2011).

Flecha, S. et al. Trends of pH decrease in the Mediterranean Sea through high frequency observational data: indication of ocean acidification in the basin. Sci. Rep. 5, 16770 (2015).

Yao, K. M. et al. Time variability of the north-western Mediterranean Sea pH over 1995–2011. Mar. Environ. Res. 116, 51–60 (2016).

Ríos, A. F. et al. Decadal acidification in the water masses of the Atlantic Ocean. P.N.A.S. 112(32), 9950–9955 (2015).

Baumann, H. & Smith, E. M. Quantifying metabolically driven pH and oxygen fluctuations in US nearshore habitats at diel to interannual time scales. Est. Coasts 41, 1102–1117 (2017).

Lowe, A. T., Bos, J. & Ruesink, J. Ecosystem metabolism drives pH variability and modulates long-term ocean acidification in the Northeast Pacific coastal ocean. Sci. Rep. 9, 963 (2019).

Santinelli, C., Nannicini, L. & Seritti, A. DOC dynamics in the meso and bathypelagic layers of the Mediterranean Sea. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 57(16), 1446–1459 (2010).

Schneider, A., Tanhua, T., Roether, W. & Steinfeldt, R. Changes in ventilation of the Mediterranean Sea during the past 25 year. Ocean Sci. 10(1), 1–16 (2014).

García-Lafuente, J., Sánchez Román, A., Díaz del Río, G., Sannino, G. & Sánchez Garrido, J. Recent observations of seasonal variability of the Mediterranean outflow in the Strait of Gibraltar. J. Geophys. Res. 112(C10), C10005 (2007).

MEDOC group. Observation of Formation of Deep Water in the Mediterranean Sea, 1969. Nature 227(5262), 1037–1040 (1970).

Leaman, K. D. & Schott, F. A. Hydrographic Structure of the Convection Regime in the Gulf of Lions: Winter 1987. J. Phys. Oceanog. 21(4), 575–598 (1991).

Huertas, I. E. et al. Atlantic forcing of the Mediterranean oligotrophy. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26(2), GB2022 (2012).

de la Paz, M., Huertas, I. E., Flecha, S., Ríos, A. F. & Pérez, F. F. Nitrous oxide and methane in Atlantic and Mediterranean waters in the Strait of Gibraltar: Air-sea fluxes and inter-basin exchange. Prog. Oceanog. 138(Part A), 18–31 (2015).

Clayton, T. D. & Byrne, R. H. Spectrophotometric seawater pH measurements: total hydrogen ion concentration scale calibration of m-cresol purple and at-sea results. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 40(10), 2115–2129 (1993).

Lewis, E., Wallace, D. & Allison, L.J. Program developed for CO2 system calculations, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, managed by Lockheed Martin Energy Research Corporation for the US Dep. of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tenn (1998).

Mintrop, L., Pérez, F. F., González-Dávila, M., Santana-Casiano, J. M. & Körtzinger, A. Alkalinity determination by potentiometry: Intercalibration using three different methods. Cien. Mar. 26(1), 23–27 (2000).

Mehrbach, C., Culberson, C. H., Hawley, J. E. & Pytkowicx, R. M. Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmospheric pressure. Limnol. Oceanogr. 18(6), 897–907 (1973).

Dickson, A. G. & Millero, F. A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep-Sea Res. Part A 34(10), 1733–1743 (1987).

Dickson, A. G. Standard potential of the reaction: AgCl(s) + 1/2 H2(g) = Ag(s) + HCl(aq), and the standard acidity constant of the ion HSO4 − in synthetic sea water from 273.15 to 318.15 K. Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics. 22, 113–127 (1990).

Benson, B. B. & Krause, D. The concentration and isotopic fractionation of oxygen dissolved in freshwater and seawater in equilibrium with the atmosphere. Limnol. Oceanogr. 29(3), 620–632 (1984).

Knap, A., Michaels, A., Close, A., Ducklow, H. & Dickson, A. Protocols for the joint global ocean flux study (JGOFS) core measurements, JGOFS, Reprint of the IOC Manuals and Guides. No. 29, UNESCO 1994, 19 (1996).

Hansen, H. P. & Koroleff, F. Determination of nutrients. In Grasshof, K., Kremling, K. & Ehrhardt, M. (eds) Methods of seawater analysis. WILEY-VCH, Weilheim, 159–228 (1999).

Gruber, N., Sarmiento, J. L. & Stocker, T. F. An improved method for detecting anthropogenic CO2 in the oceans. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 10(4), 809–837 (1996).

Anderson, L. A. & Sarmiento, J. L. Redfield ratios of remineralization determined by nutrient data analysis. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 8(1), 65–80 (1994).

Poole, R. & Tomczak, M. Optimum multiparameter analysis of the water mass structure in the Atlantic Ocean thermocline. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 46(11), 1895–1921 (1999).

Flecha, S. et al. Anthropogenic carbon inventory in the Gulf of Cádiz. J. Mar. Syst. 92(1), 67–75 (2012).

Pérez, F. F., Álvarez, M. & Ríos, A. F. Improvements on the back-calculation technique for estimating anthropogenic CO2. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 49, 859–875 (2002).

Rhein, M. & Hinrichsen, H. Modification of Mediterranean Water in the Gulf of Cadiz, studied with hydrographic, nutrient and chlorofluoromethane data. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 40(2), 267–291 (1993).

Santana-Casiano, J. M., Gonzalez-Davila, M. & Laglera, L. M. The carbon dioxide system in the Strait of Gibraltar. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 49(19), 4145–4161 (2002).

Lee, K. et al. An Updated Anthropogenic CO2 Inventory in the Atlantic Ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17(4) (2003).

Álvarez-Salgado, X. A. et al. New insights on the mineralization of dissolved organic matter in central, intermediate, and deep water masses of the northeast North Atlantic. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58(2), 681–696 (2013).

Bruno, M. et al. The boiling-water phenomena at Camarinal Sill, the strait of Gibraltar. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 49(19), 4097–4113 (2002).

García‐Lafuente, J., Sánchez‐Román, A., Naranjo, C. & Sánchez‐Garrido, J. C. The very first transformation of the Mediterranean outflow in the Strait of Gibraltar. J. Geophys. Res. 116(C7), C07010 (2011).

Macias, D., Garcia, C. M., Echevarrıia, F., Vazquez-Escobar, A. & Bruno, M. Tidal induced variability of mixing processes on Camarinal Sill (Strait of Gibraltar). A pulsating event. J. Mar. Sys. 60, 177–192 (2006).

Jones, D. C., Ito, T., Takano, Y. & Hsu, W. C. Spatial and seasonal variability of the air-sea equilibration timescale of carbon dioxide. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 8(11), 1163–1178 (2014).

Bethoux, J. P., El Boukhary, M. S., Ruiz-Pino, D., Morin, P. & Copin-Montégut C. Nutrient, Oxygen and Carbon Ratios, CO2 Sequestration and Anthropogenic Forcing in the Mediterranean Sea, in The Mediterranean Sea, edited by A. Saliot, pp. 67–86, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg (2005).

Khatiwala, S. et al. Global ocean storage of anthropogenic carbon. Biogeosciences 10(4), 2169–2191 (2013).

Woosley, R. J., Millero, F. J. & Wanninkhof, R. Rapid anthropogenic changes in CO2 and pH in the Atlantic Ocean: 2003–2014. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 30(1), 70–90 (2016).

Navarro, G. & Ruiz, J. Spatial and temporal variability of phytoplankton in the Gulf of Cadiz through remote sensing images. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 53(11), 1241–1260 (2006).

Ribas-Ribas, M., Anfuso, E., Gomez-Parra, A. & Forja, J. M. Tidal and seasonal carbon and nutrient dynamics of the Guadalquivir estuary and the Bay of Cádiz (SW Iberian Peninsula). Biogeosciences 10, 4481–4491 (2013).

Flecha, S., Huertas, I. E., Navarro, G., Morris, E. P. & Ruiz, J. Air–Water CO2 Fluxes in a highly heterotrophic estuary. Est. Coasts 38, 2295–2309 (2015).

Sutton, A. J. et al. Autonomous Seawater pCO2 and pH Time Series From 40 surface buoys and the emergence of anthropogenic trends. Earth System Science Data, 421–439 (2019).

Matsumoto, K. & Gruber, N. How accurate is the estimation of anthropogenic carbon in the ocean? An evaluation of the ΔC* method. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19(3) (2005).

González-Dávila, M., Santana-Casiano, J. M., Rueda, M. J. & Llinás, O. The water column distribution of carbonate system variables at the ESTOC site from 1995 to 2004. Biogeosciences 7(10), 3067 (2010).

Vázquez-Rodríguez, M., Pérez, F., Velo, A., Ríos, A. & Mercier, H. Observed acidification trends in North Atlantic water masses. Biogeosciences 9(12), 5217–5230 (2012).

Kapsenberg, L., Alliouane, S., Gazeau, F., Mousseau, L. & Gattuso, J.-P. Coastalocean acidification and increasing total alkalinity in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Science 13(3), 411–426 (2017).

Powley, H. R., Krom, M. D. & Van Cappellen, P. Understanding the unique biogeochemistry of the Mediterranean Sea: Insights from a coupled phosphorus and nitrogen model. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31(6), 1010–1031 (2017).

Sanchez‐Vidal, A. et al. Impact of dense shelf water cascading on the transfer of organic matter to the deep western Mediterranean basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L05605 (2008).

Pusceddu, A. et al. Ecosystem effects of dense water formation on deep Mediterranean Sea ecosystems: an overview. Adv. Oceanog. Limnol. 1(1), 67–83 (2010).

Naranjo, C., Sammartino, S., García-Lafuente, J., Bellanco, M. J. & Taupier-Letage, I. Mediterranean waters along and across the Strait of Gibraltar, characterization and zonal modification. Deep-Sea Res Part I 105, 41–52 (2015).

Skliris, N. & Beckers, J. M. Modelling the Gibraltar Strait/Western Alboran Sea ecohydrodynamics. Oce. Dyn. 59(3), 489–508 (2009).

Luna, G. M. et al. The dark portion of the Mediterranean Sea is a bioreactor of organic matter cycling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26(2), GB2017 (2012).

Schroeder, K., Chiggiato, J., Bryden, H., Borghini, M. & Ismail, S. B. Abrupt climate shift in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Reports 6, 23009 (2016).

Millot, C. Models and data: a synergetic approach in the western Mediterranean Sea. In Ocean Processes in Climate Dynamics: Global and Mediterranean Examples (pp. 407–425). Springer, Dordrecht (1994).

Millot, C. Circulation in the western Mediterranean Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 20(1–4), 423–442 (1999).

Stratford, K., Williams, R. G. & Drakopoulos, P. G. Estimating climatological age from a model-derived oxygen–age relationship in the Mediterranean. J. Mar. Syst. 18(1–3), 215–226 (1998).

Stöven, T. & Tanhua, T. Ventilation of the Mediterranean Sea constrained by multiple transient tracer measurements. Ocean Sci. 10, 439–457 (2014).

Perez, F. F. et al. Meridional overturning circulation conveys fast acidification to the deep Atlantic Ocean. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25493 (2018).

Hayes D. R. et al. Review of the Circulation and Characteristics of Intermediate Water Masses of the Mediterranean: Implications for Cold-Water Coral Habitats. In Orejas, C., Jiménez, C. (eds) Mediterranean Cold-Water Corals: Past, Present and Future. Coral Reefs of the World, vol 9. Springer, Cham (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the crews of all the research vessels involved in this study. We also thank Maria Ferrer, Antonio Moreno and David Roque for their assistance with sample collection and analysis. Funding for this work was provided by the European Commission through the projects CARBOOCEAN (FP6-511176), CARBOCHANGE (FP7-264879), PERSEUS (FP7-287600) and COMFORT (H2020-820989) and by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (CTM2006-28141-E/MAR, CTM2016-75487-R). S.F acknowledges the financial support of Canon Foundation in Europe Research Fellowships Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.F. and I.E.H. contributed equally to this work. They both conceived of research, collected and analysed data and wrote the manuscript. F.F.P. and A.M. interpreted and discussed data. Ah. M. provided data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Flecha, S., Pérez, F.F., Murata, A. et al. Decadal acidification in Atlantic and Mediterranean water masses exchanging at the Strait of Gibraltar. Sci Rep 9, 15533 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52084-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52084-x

This article is cited by

-

Contrasting patterns in pH variability in the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2024)

-

Anthropogenic acidification of surface waters drives decreased biogenic calcification in the Mediterranean Sea

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

pH trends and seasonal cycle in the coastal Balearic Sea reconstructed through machine learning

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.