Abstract

Modern megaherbivore community richness is limited by bottom-up controls, such as resource limitation and resultant dietary competition. However, the extent to which these same controls impacted the richness of fossil megaherbivore communities is poorly understood. The present study investigates the matter with reference to the megaherbivorous dinosaur assemblage from the middle to upper Campanian Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada. Using a meta-analysis of 21 ecomorphological variables measured across 14 genera, contemporaneous taxa are demonstrably well-separated in ecomorphospace at the family/subfamily level. Moreover, this pattern is persistent through the approximately 1.5 Myr timespan of the formation, despite continual species turnover, indicative of underlying structural principles imposed by long-term ecological competition. After considering the implications of ecomorphology for megaherbivorous dinosaur diet, it is concluded that competition structured comparable megaherbivorous dinosaur communities throughout the Late Cretaceous of western North America.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The question of which mechanisms regulate species coexistence is fundamental to understanding the evolution of biodiversity1. The standing diversity (richness) of extant megaherbivore (herbivores weighing ≥1,000 kg) communities appears to be mainly regulated by bottom-up controls2,3,4 as these animals are virtually invulnerable to top-down down processes (e.g., predation) when fully grown. Thus, while the young may occasionally succumb to predation, fully-grown African elephants (Loxodonta africana), rhinoceroses (Ceratotherium simum and Diceros bicornis), hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius), and giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) are rarely targeted by predators, and often show indifference to their presence in the wild5. Rather, food resources tend to be limiting to such large animals, particularly during the dry season when food is less abundant2,3.

It is axiomatic that our understanding of modern megaherbivore ecology is based entirely on the study of mammal communities, these being the only megaherbivores alive today5. However, for most of the Mesozoic, only dinosaurs occupied this category, and it is not obvious that megaherbivorous dinosaur communities were similarly immune to those same top-down processes that their living counterparts shirk today. Of particular note is the fact that dinosaurian predators were much larger than those of today6 (Fig. 1), and likely would have posed a significant threat to even the largest herbivores of their time (with the possible exception of the biggest sauropods). This is especially true if large theropods were capable of cooperative hunting, a hypothesis that has garnered some support from both bonebed and trackway evidence7,8,9. Large theropod bite marks have also been recorded on the bones of massive ceratopsids, hadrosaurids, sauropods, and stegosaurs (although at least some instances are undoubtedly the result of scavenging)10,11.

Ratios of log-transformed body mass of largest herbivore (in blue) to largest carnivore (in orange) for select fossil and modern ecosystems. Examples (A) and (B) illustrate dinosaur ecosystems; examples (C)–(E) illustrate mammal ecosystems. Note that herbivore:carnivore size ratios are closer to 1 in the dinosaur ecosystems; that is, predator and prey are more nearly equal in size. Silhouettes not to scale. Abbreviation: Fm, Formation.

The community ecology, and particularly the coexistence of its constituent species, has proved especially perplexing as it relates to the megaherbivorous dinosaur assemblage of the Late Cretaceous island continent of Laramidia. This diminutive landmass (4 million–7.7 million km2 12,13) resulted from the flooding of the North American Western Interior between approximately 100 and 66 million years ago. Megaherbivorous ankylosaurs, ceratopsids, and hadrosaurids were particularly abundant here, and account for the majority of the fossil assemblage, in terms of both diversity and biomass. The megaherbivore diversity of various well-sampled terrestrial mammal assemblages pales by comparison, even given larger habitable areas14 (Fig. 2). The problem of megaherbivore coexistence on Laramidia is further compounded by the large nutritional requirements of these animals14,15,16, and their high population densities17,18,19, which would have placed increased pressure on the resource base.

Predatory dinosaurs were common on Laramidia20, but only the large (2,000–8,000 kg) tyrannosaurids were capable of felling the megaherbivores. However, whether they did so with such frequency as to shape the structure of the megaherbivore assemblage is unclear. If the megaherbivorous dinosaurs were instead resource-limited, as contended here, then the following argument might be proffered:

P1. If dietary resources on Laramidia were limiting to megaherbivores, then species overlap in ecomorphospace should have been minimized, which would have reduced resource competition and facilitated dietary niche partitioning among sympatric species.

P2. Where like ecomorphotypes did coexist, their sympatry should have been short-lived or implicated only rare taxa, due to competitive constraints.

P3. Overlap in ecomorphospace was limited.

P4. Similar ecomorphotypes were incapable of prolonged coexistence.

C: Therefore, dietary resources were limiting and competition regulated megaherbivore diversity on Laramidia.

In this syllogism, P1 and P2 follow from Gause’s competitive exclusion principle21. P1 assumes that ecomorphotype reflects niche occupation, which is generally well-supported22. P1 and P3 are insufficient to run the argument on their own because it is possible that negligible overlap in ecomorphospace can occur stochastically via migration, despite any underlying organizing principles23; the multidimensionality of niche hyperspace is such that the probability that any two species will occupy the same space is low due to chance alone24. Therefore, to demonstrate the effect of competition for limited resources, it is also necessary to show that like ecomorphotypes cannot coexist indefinitely (P2), owing to the preoccupation of niche space. The remainder of this paper will focus on demonstrating P3 and P4, which are simply the manifestations of P1 and P2, respectively.

Materials and Methods

Model system

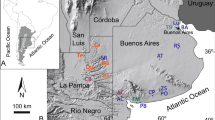

Laramidia stretched from what is now the North Slope of Alaska to Mexico. Dinosaur assemblages from intermontane, alluvial and coastal plain deposits have been found throughout this ancient landmass, but among the best sampled and consequently most diverse is that of the Dinosaur Park Formation (DPF, middle to upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. The DPF is an alluvial-coastal plain deposit that records the third order transgressive event of the Western Interior Seaway (Bearpaw phase). Recent estimates, based on 40Ar/39Ar dating, place the lower boundary of the DPF at ~77 Ma and the upper at ~75.5 Ma25. At present, over 30 herbivorous and omnivorous dinosaur species are recognized from the DPF26. Ongoing biostratigraphic work has shown that these taxa were not all contemporaneous, but that different species are restricted to different horizons within the formation27,28 (Fig. 3). Mallon et al.29 used ordination and clustering methods to divvy the megaherbivore assemblage of the DPF into two zones, the older Megaherbivore Assemblage Zone 1 (MAZ-1) and the younger Megaherbivore Assemblage Zone 2 (MAZ-2). Despite minor discrepancies, these closely matched the zones previously identified by Ryan and Evans27 based on a qualitative assessment of species distribution. Establishment of the MAZs limits the confounding effects of time-averaging to a scale of approximately 600 Kyr29, while creating an objective and meaningful framework in which to consider ecological interactions within the DPF megaherbivore assemblage. The representative fauna, high biodiversity, and exceptional stratigraphic control thus combine to make the DPF an ideal model system for studying species interactions during the Late Cretaceous of Laramidia. These conditions are not currently met elsewhere in the fossil record of the North American Western Interior or, indeed, elsewhere in the dinosaur fossil record.

Biostratigraphy of megaherbivores from the Dinosaur Park Formation, in the area of Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta. Note that stratigraphic overlap between members of the same family (in the case of ankylosaurs) or subfamily (in the case of ceratopsids and hadrosaurids) is limited, only involving examples of rare or short-lived species. Abbreviations: MAZ, Megaherbivore Assemblage Zone. Modified from Mallon et al.29.

Analysis

The megaherbivore assemblage of the DPF has been the subject of intense interest lately, particularly as it relates to the matter of niche partitioning. Recent studies of this assemblage (primarily stemming from the PhD research of Mallon30), have examined variability in feeding height31, skull and beak morphology32,33, tooth wear34, and jaw mechanics35. In order to discern more completely the matter of megaherbivore niche partitioning, data from these studies were combined into a single meta-analysis. Body mass is also of great ecological importance5,36, and was estimated for each specimen, where possible. This was done using the R package MASSTIMATE37, which estimates body mass using the limb bone scaling formula of Campione and Evans38. Twenty-one variables were considered in total (Table 1). To minimize the amount of missing information while maximizing the size of the dataset, only those specimens with ≥50% missing data were included, for a total of 75 specimens representing 14 genera. The complete 21 × 75 matrix is available in Supplementary Data S1.

To assess the extent to which different taxonomic groups occupied ecomorphospace, non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was used to ordinate the data with the metaMDS() function in the vegan package39 for R v. 0.99.90240. NMDS was chosen because it is robust to missing data and can handle mixed variable datasets on account of its use of ranked distances over the original distance values. The variables were both left untransformed and subjected to z-score transformation to equalize their weights41,42. Arguably, the former approach better captures the ecological relationships of the taxa considered here because it does not suppress those variables that have a dominant effect on niche differentiation (e.g., body mass)5,36. A Euclidean distance metric was used in the calculation of the initial dissimilarity matrix, and dimensionality (k) was allowed to vary between k = 2 and k = 4 to assess its influence on morphospace reconstruction. Because NMDS is easily trapped on local optima, the analysis was run iteratively using a minimum of 10,000 random starts until two convergent solutions were reached (no convergent solutions were reached at k > 4 for the untransformed data). Unlike the more conventional principal component analysis, NMDS does not yield eigenvectors; rather, its axes are arbitrary, and variable loadings on those axes cannot be deduced43. The relationships of variables to axes were instead estimated using Kendall’s tau rank correlation41,44.

The distribution of the data was considered at different taxonomic (family/subfamily + suborder/family + genus) and temporal (time-averaged/MAZ-1/MAZ-2) scales to seek compromise between resolution and sample size. Numerous studies31,32,33,34,35 were unable to demonstrate significant ecomorphological differences at the species level, so those differences were not investigated here. Comparisons were also made of taxa between MAZ-1 and -2 to assess changes in ecomorphospace occupation through time. Significant (α = 0.05) taxonomic and temporal differences in NMDS scores were sought using one-way permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), and post-hoc pairwise comparisons were made with and without partial Bonferroni correction. Statistical comparisons and correlations were conducted in PAST v. 3.1545.

Results

Time-averaged ecomorphospace

The results obtained here are broadly consistent with those reported elsewhere using subsets of the current dataset31,32,33,34,35. Likewise, the results stemming from the untransformed data largely agree with those from the transformed data, and so only the former are reported here. Full statistical details are provided in Supplementary Data S1 (untransformed data) and S2 (transformed data). NMDS stress values vary from poor (0.23) at k = 2 to good (0.13) at k = 4 (Fig. 4), although the ordination results are all generally comparable. At all values of k, there is statistical support for taxonomic separation in the time-averaged ecomorphospace (p < 0.0001). Pairwise comparisons show that Ankylosauria, Ceratopsidae, and Hadrosauridae are all significantly distinct from one another (p < 0.0001 for all k), and there is limited or no overlap between them in ecomorphospace (Fig. 5). Ankylosaurs consistently plot well apart from ceratopsids along the first NMDS axis (most strongly and positively correlated with metrics of facial length, skull height, and coronoid process height; Fig. 6) with hadrosaurids (particularly lambeosaurines) spanning the distance between them. Ceratopsids are best separated from hadrosaurids along the second axis (most strongly correlated with metrics of posterior skull breadth, minimum relative bite force, and beak shape; Fig. 6), with some overlap occurring at higher values of k. Ankylosaurs plot between them. At k = 3 and k = 4, there is some overlap of Ceratopsidae and Hadrosauridae (particularly Hadrosaurinae) along the second axis (Fig. 5).

Kendall’s tau correlation map showing relationships between NMDS scores and the 21 ecomorphological variables used in this study. Abbreviations after Table 1.

There is generally good taxonomic separation even within these higher level taxa (Table 2). For all values of k, ankylosaurids and nodosaurids are well separated along the second NMDS axis, with minimal overlap (Fig. 5), although statistical significance is manifest only at k = 2 and k = 3 (p < 0.05, uncorrected), likely reflective of small sample size. Hadrosaurines and lambeosaurines also occupy distinct (p < 0.001 for all k), yet overlapping, areas of morphospace; they are best separated along the first (for k = 2) or second (for k = 3 and k = 4) axes. The separation of centrosaurines and chasmosaurines is weak; the two groups are statistically distinguishable (p < 0.05, uncorrected) only at k = 4, although the p-value at k = 3 approaches significance (Table 2), and all p-values are likely affected by small sample size. Chasmosaurines plot more distally on axis 2 than centrosaurines, particularly at higher values of k (Fig. 5). Taxonomic separation is reduced along higher NMDS axes (i.e., 3 and 4; Supplementary Data S1), and axis score correlation with the original ecomorphological variables is correspondingly depressed (Fig. 6). Additionally, there is statistically poor separation of genera within the ankylosaur families, and within the ceratopsid and hadrosaurid subfamilies (Supplementary Data S1).

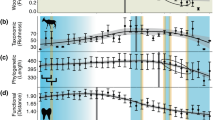

Temporal comparisons

The patterns observed in the time-averaged sample above are largely stable through time, such that the various ankylosaurs, ceratopsids, and hadrosaurids occupy the same general regions of ecomorphospace between the lower (MAZ-1) and upper (MAZ-2) parts of the DPF, a timespan of approximately 1.5 Myr (Fig. 7). At k = 2, there is a small but significant (N = 7, F = 3.65, p < 0.05) shift of Chasmosaurinae along the second axis between MAZ-1 and -2. There are notably fewer individuals sampled within MAZ-2, reflective of taphonomic and sampling biases in the muddy host unit28. Nodosaurids are entirely absent from the MAZ-2 sample, and ankylosaurids (N = 1) and centrosaurines (N = 2) are likewise rare.

Time-constrained ecomorphospace comparisons between MAZ-1 and -2 for different values of k. Dashed lines in MAZ-2 ecomorphospaces indicate original taxon distribution in MAZ-1. Note that megaherbivore distribution in ecomorphospace varies little through time. Silhouettes not to scale. Colours after Fig. 5.

Further insight can be gained by cross-referencing the biostratigraphic distribution of megaherbivores in the DPF with the ecomorphological patterns observed in MAZ-1 and -2. At any horizon within the DPF, there is typically only a single contemporaneous species of Ankylosauridae, Nodosauridae, Centrosaurinae, Chasmosaurinae, Hadrosaurinae, and Lambeosaurinae (Fig. 3). Thus, the ecomophological patterns and relationships seen in Figs 5 and 7 are likely representative of the megaherbivore standing crop at any given time. Where exceptions to this pattern occur, they typically involve very rare (e.g., Panoplosaurus mirus, Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus, Chasmosaurus canadensis, Lambeosaurus clavinitialis, Parasaurolophus walkeri) or short-lived (e.g., Corythosaurus intermedius) species (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Palaeoecology of the DPF megaherbivore assemblage

If resources were limiting during the Late Cretaceous of western North America, there should be minimal evidence for significant ecomorphological overlap among sympatric megaherbivores. Or, where overlap occurs, it should be short-lived on account of competitive exclusion. Both of these premises (P1 and P2 in the introductory syllogism) are borne out in this study (P3 and P4), suggesting both that competition had a role in shaping the megaherbivore community structure of the Late Cretaceous, and that the high megaherbivore standing diversity (richness) reported here was enabled through niche partitioning. This is not a trivial discovery; it has been hypothesized that the high megaherbivore diversity on Laramidia resulted from (non-limiting) resource abundance, due to elevated primary productivity46, to the exceptionally low metabolic requirements of dinosaurs12,16, or both46,47. Predation and disease are also capable of reducing herbivore abundance and alleviating pressure on the resource base48,49, but these mechanisms have not been implicated in the structuring of dinosaur communities. Regardless, none of these hypotheses predict the structural patterns noted here. Although dietary niche partitioning has been posited in other ancient, non-mammalian communities42,50,51, this study is among the first to demonstrate its operation within a single assemblage using a meta-analytic approach. Further evidence for resource limitation during the Late Cretaceous stems from a consideration of ecological energetics14,52.

Ankylosaurs and ceratopsids appear to have been most ecologically distinct, given how far they plot from one another in the NMDS analyses. In a sense, this might be surprising: ankylosaurs and ceratopsids are both large, obligate quadrupeds that fed low to the ground31, so one might expect that they would share similar ecologies, particularly when compared to the facultatively quadrupedal hadrosaurids. Nevertheless, there also exists a bevy of ecomorphological differences between the first two taxa. Ankylosaurs had smaller, relatively wider skulls with broader muzzles that would have allowed them to feed less selectively32,33. Ankylosaur dentaries were relatively deeper than those of ceratopsids, yet were capable of producing far lower bite forces35. Their tooth rows were shorter, and the teeth were simple and loosely arranged compared to the elongate and complex dental batteries of the ceratopsids, whose dentition was strictly limited to shearing, as reflected by the microwear34. These functional differences allowed ankylosaurs and ceratopsids to partition the low browsing guild.

The fact that hadrosaurids share certain features in common with ankylosaurs (e.g., wide muzzles33, higher dental microwear pit counts34) and others in common with ceratopsids (e.g., large and elongate skulls32, elevated bite forces35, tooth batteries34), and the fact that they exhibit a particularly large area of ecomorphospace, suggests that hadrosaurids had comparatively catholic herbivorous diets. Indeed, it is reasonable to suspect that they may have occasionally shared resources with both ankylosaurs and ceratopsids. Nevertheless, hadrosaurids were quite distinct in that they could feed at heights of up to 5 m above ground31, and their teeth were capable of crushing, grinding, and shearing34, enabling these animals access to plants not available to the other megaherbivores. In light of their particularly large sizes, generalist diets (see ‘Megaherbivorous dinosaur diets’ below), and propensity to form herds18,53,54, hadrosaurids may have had the greatest impact on structuring plant communities and the smaller fauna that inhabited them. In this sense, hadrosaurids might have served as ecosystem engineers55, much like modern elephants56,57.

Even within these higher level taxa, there is evidence for niche partitioning, particularly between members of different families and subfamilies. Ankylosaurids and nodosaurids were both restricted to low browsing, yet the former differed from the latter in having wider, squarer beaks33, weaker jaws35, and smaller, more cusp-like teeth34,58. Hadrosaurines and lambeosaurines were able to exploit a wider range of vegetation strata31, and could therefore divvy food resources in that way. Hadrosaurines are further distinguishable from lambeosaurines in having larger skulls with less ventrally deflected beaks32, and more numerous, but finer microwear scratches34. The evidence for niche partitioning between centrosaurines and chasmosaurines is slim, but statistically significant (Table 2), in spite of the fact that previous studies failed to find significant ecomorphological differences between the two groups. In this case, it appears that near-significant results from those previous studies multiplicatively combined to yield significance here. Thus, although Mallon and Anderson32 could not demonstrate that centrosaurines have deeper skulls than chasmosaurines (p = 0.077), and Mallon and Anderson34 could not quite show that centrosaurines have statistically higher microwear scratch counts than chasmosaurines (p = 0.051), the synthesis of these data in a larger meta-analysis more convincingly establishes the distinct ecomorphologies of the two groups. This point echoes that made by Fraser and Theodor59 concerning ungulate dietary proxies.

There is no statistical evidence for niche partitioning below the family level among ankylosaurs or below the subfamily level among ceratopsids and hadrosaurids. This insignificance is not a simple upshot of low sample size because genera within these clades overlap considerably in morphospace (but not temporally).

Megaherbivorous dinosaur diets

In light of the evidence for dietary niche partitioning presented here, the question naturally arises as to what the megaherbivores of the DPF ate. Redundancy in the form-function complex60, lack of modern analogues, and incomplete knowledge of Late Cretaceous terrestrial environments in North America greatly hamper efforts to reconstruct the dietary habits of these dinosaurs. This has not prevented anyone from trying (Table 3). What follows is an attempt to say something constructive about the diets of the DPF megaherbivores, using a total evidence approach. To the extent that the ecomorphotypes considered here are not descriptive of clade members that occur outside the DPF (e.g., narrow-snouted, non-ankylosaurine ankylosaurids58), or that other fossil assemblages contain potential foodstuffs not present in the study area (e.g., palms, cycadophytes), these comments do not apply. The inferences are necessarily broad, owing to the incomplete nature of the fossil record. Dietary subtleties between closely related species, or that vary with geography or seasonality, are wholly ignored.

Ankylosauria

Because of their small and supposedly weak teeth, ankylosaurs have traditionally been attributed a diet of soft, possibly aquatic plants (Table 3). However, this seems unlikely for two reasons. First, distribution data indicate that ankylosaurs may have preferred inland settings29,61,62 and probably did not habitually dwell in the wet, swampy coastal plain settings where aquatic plants were most common (but see Butler and Barrett63). Second, ankylosaurs exhibit a suite of features suggestive of a more resistant plant diet, including a transversely wide skull, deep mandible with dorsally bowed tooth row32, and ossified secondary palate64,65, all of which would have dissipated stress associated with resilient foodstuffs. The phylliform teeth of ankylosaurs, although similar to those of iguanines in shape, are also heavily worn, indicating that ankylosaurs were more effective at comminuting plant material than their lepidosaurian counterparts34. Finally, the laterally expanded gut of the ankylosaurs would have increased both retention time and the space available for cellulolytic microflora, further aiding in the breakdown of resistant plants66.

In fact, given differences in the cranial anatomy of ankylosaurids and nodosaurids, ankylosaur diets were probably more varied than traditionally assumed. Ankylosaurids (represented in the DPF by Euoplocephalus tutus and the rare Anodontosaurus lambei and Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus) are interpreted here as consumers of low-growing ferns (Polypodiales), as evidenced by several features. First, all ankylosaurs were restricted to feeding at heights < 1 m above the ground31, and must therefore have browsed within the herb layer. Second, the wide, square beaks of ankylosaurids33 are suggestive of high intake rates typically associated with consumers of low-quality (high-fibre) vegetation. The data of Hummel67 indicate that, compared to most other vascular plants, ferns are less nutritious, being lower in metabolizable energy and higher in fibre. They therefore seem likely as ankylosaurid fodder. Ferns and other ‘pteridophytes’ from the DPF comprise ~39% of the total palynofloral diversity68, and include examples of Osmundaceae (cinnamon ferns), Schizaeaceae (climbing ferns), Gleicheniaceae, and Cyatheaceae, among others69. The interpretation of ankylosaurids as fern consumers agrees with a cololite found inside the gut of a small (~300 kg70), Early Cretaceous ankylosaurid from Australia71. In addition to an abundance of vascular tissue (possibly leaves), the fossil contains angiosperm fruits, small seeds, and probable fern sporangia. It is likely that, on account of their much larger size (~2,300 kg72), the DPF ankylosaurids could tolerate low-quality fern material in much greater proportion.

One way that nodosaurids (represented in the DPF by Panoplosaurus mirus and Edmontonia rugosidens) differ from ankylosaurids (particularly Late Cretaceous ankylosaurines) is in having narrower, more rounded beaks33,58,73,74,75,76. Nodosaurids therefore appear to have been more selective than these ankylosaurids, and probably consumed more nutritious vegetation, such as shrubby dicotyledonous (dicot) browse. This interpretation would also account for other aspects of nodosaurid morphology. For example, the taller coronoid process suggests the ability to generate higher bite forces possibly associated with a diet of woody browse32,35,58, and the distally dilated process of the vomers may have dissipated stresses associated with those higher bite forces77,78. The mesiodistally expanded, bladed teeth of nodosaurids also suggest an incipient ability to cope with the crack-stopping mechanism of woody plant material34,79. To be sure, nodosaurids do not share the same highly-modified morphology of ceratopsids for rending woody browse (see Ceratopsidae below), so it is unlikely that nodosaurids fed exclusively on this type of vegetation. Instead, both ankylosaurids and nodosaurids likely consumed mostly herbaceous ferns, with the latter supplementing their diet with dicot browse. The relatively high number of dental microwear pits in both these taxa indicates that they may also have eaten fruits or seeds on occasion34.

Ceratopsidae

Several lines of evidence point to the fact that ceratopsids subsisted on particularly tough vegetation. The skull was massive—more so than in any other animal from the DPF—indicating that these animals could generate absolutely high bite forces32. The lower jaw was also constructed in such a way as to produce relatively high bite forces35. The triangular beak was narrow, and could be used to selectively crop coarse plant matter33, a feeding strategy shared with black rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis). Yet, probably more than any other feature, the shearing dentition of ceratopsids has played a key role in the inference to their diets. It is commonly and correctly understood that their dentition was particularly suitable to fracturing the toughest plant tissues34,80,81. Among the plant foods most regularly attributed to ceratopsid diets are cycadophytes and palms (Arecaceae; Table 3); the fronds of the former are very fibrous and not particularly nutritious82. However, probably neither of these was consumed by ceratopsids from the DPF for the simple reason that compelling evidence for the existence of these plants in the formation is lacking69,83,84,85,86. Furthermore, living cycads are particularly toxic87,88, and it is likely that their fossil forbearers were as well. Therefore, even if cycads were available, they were probably not frequently eaten.

In light of these considerations, Dodson83,84,85 suggested that ceratopsids most regularly consumed woody angiosperms. This seems like a more reasonable interpretation for various reasons. First, angiosperms were widespread by the Late Cretaceous, and were particularly abundant in the floodplain environments89 that ceratopsids are known to have frequented61,62,90. Second, it is likely that angiosperms from the DPF were herbaceous or shrubby in habit because angiosperm wood corresponding to trees is unknown from the formation69. These flowering plants were therefore easily within reach of the ceratopsid cropping mechanism31. Third, the woody branches and twigs of angiosperm shrubs would have required a bladed dentition for fracture79, and the ceratopsid dental battery appears optimally suited to the task34,81. Common angiosperms in the DPF include relatives of maples (Aceraceae), beeches (Fagaceae), elms (Ulmaceae), lilies (Liliaceae), sedges and reeds (Cyperaceae), among others69. Conifer (Pinales) and ginkgo (Ginkgoaceae) saplings may have been consumed as well, though probably less frequently, given their generally slower replacement rates88. Although some66,91 have posited coevolutionary scenarios between early angiosperms and ornithischian dinosaurs (including ceratopsids), there is no solid evidence for this92,93.

Possible evidence for dietary niche partitioning between coexisting centrosaurines and chasmosaurines comes by way of their different skull proportions and dental microwear signatures; centrosaurines appear to have slightly shorter, deeper crania than chasmosaurines32, and higher microwear scratch counts34. These data are consistent with the interpretation that centrosaurines ate tougher, more fibrous vegetation than chasmosaurines, requiring more oral processing94. The high-angled slicing surfaces of centrosaurine predentaries13,95 further support this interpretation.

Hadrosauridae

Previous attempts at inferring hadrosaurid diets have varied widely (Table 3). Accordingly, hadrosaurids are interpreted as having been the least selective of the megaherbivores from the DPF; they likely subsisted on a broad range of plant tissues. Evidence for this comes by way of their large body sizes96 (which typically equates to a broad dietary range5), correspondingly large feeding envelopes31, intermediate beak morphologies32,33, efficient jaw mechanics35, and complex tooth batteries capable of crushing, grinding, and shearing functions34. Hadrosaurids also appear to have been most cosmopolitan in their distribution along the alluvial-coastal plain62,90, and were therefore tolerant of a wide range of habitats.

Although hadrosaurids could have effectively eaten any plants within reach, it makes sense that they would have preferred more digestible plants in order to maximize their energy intake and meet their large nutritional requirements. Hummel et al.82 provide data on Mesozoic plant digestibility, derived from living relatives of fossil taxa. Accounting for such limiting factors as temporal and geographic availability, and growth height, hadrosaurids most likely favoured horsetails (Equisetum spp.), forbs, ginkgo and conifer (pines, cypresses, and cheirolepids) saplings, and dicot browse, which were the most nutritious plants available. Hummel et al.82 suggested that horsetails were unlikely fodder for dinosaurs that chewed their food (e.g., ceratopsids and hadrosaurids) because the high silica content would have produced excessive tooth wear. However, the rapid tooth replacement rates of these animals, on the order of every 50–80 days97, probably would have offset this problem.

Reported examples of hadrosaurid gut contents9,97,98 include abundant conifer material, although the origin of this material (whether autochthonous or not) remains questionable. However, coprolites attributable to hadrosaurids99,100 also contain abundant conifer material (including fungally decayed wood), and it is likely that these plants formed a staple of hadrosaurid diets. Angiosperm seeds and fruits also have been reported in hadrosaurid gut contents98,101, as well as unidentified leaf material102. Bearing in mind the difficulties associated with interpreting these fossils103, these contents lend credibility to the interpretation of hadrosaurids as generalist browsers, perhaps even occasionally including animal protein in their diets104.

Coexisting hadrosaurines and lambeosaurines from the DPF differ markedly in the development of their cranial ornamentation27,105, but the morphological differences that distinguished their feeding ecologies are somewhat more subtle. To this end, hadrosaurines had relatively larger and more protracted skulls than lambeosaurines, with less ventrally deflected beaks32,106. These features may suggest that lambeosaurines spent more time feeding on herbaceous vegetation near to the ground, while hadrosaurines habitually extended their long jaws into the boughs of shrubs and trees. Given their broad feeding envelopes31, these subfamilies were certainly capable of avoiding niche overlap in this way. Dental microwear evidence further supports this reasoning; scratches on the teeth of the hadrosaurine Prosaurolophus maximus are fewer and finer than those of the contemporaneous lambeosaurine Lambeosaurus lambei34, which correlates with higher browsing in living ungulates107.

Spatiotemporal patterns of the Laramidian megaherbivore assemblage

To what extent were the patterns and processes that operated within the DPF megaherbivore assemblage representative of other assemblages in Laramidia? This question may be considered from both spatial and temporal perspectives.

A recent review of the geochronology of the Western Interior of North America by Fowler25 suggests that the Judithian (middle to upper Campanian) DPF is penecontemporaneous with the fossiliferous upper Two Medicine and upper Judith River formations in Montana, the lower to middle Kaiparowits Formation in Utah, and the middle Aguja Formation in Texas. Of these, the local biostratigraphy has been presented for the first three formations25,108,109,110. Although the megaherbivore assemblages from each of these formations are relatively poorly sampled and not necessarily time-equivalent, they are nonetheless close enough to warrant comparison. Examination of the respective assemblages reveals the same predictable suite of sympatric ankylosaurids and nodosaurids, centrosaurines and chasmosaurines, and hadrosaurines and lambeosaurines reported in the DPF (albeit, with different representative species, where determinable) (Table 4). Typically, there is, at most, only one common representative of these taxa; where there are two or more representative species, all but one at most are rare. Thus, the megaherbivore community structure noted in the DPF does not appear to be spatially restricted within Laramidia.

The time at which the predictable community structure noted here became established remains elusive. The diverse megaherbivore assemblage of the DPF is effectively the earliest such assemblage known from Upper Cretaceous deposits. Slightly earlier deposits (e.g., Milk River, Foremost, and Oldman formations in Alberta, lower Two Medicine and lower Judith River formations in Montana, Wahweap Formation in Utah, lower Aguja Formation in Texas) are comparatively poorly sampled, and although they contain evidence for various ankylosaurs, ceratopsids, and hadrosaurids111, the structure of these communities is not well understood.

The megaherbivore community structure exemplified by the DPF evidently evolved in a gradual and piecemeal fashion. Nodosaurids and ankylosaurids date back to the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of North America, respectively, although their points of origin are ambiguous112. Their co-occurrence likewise dates to the Early Cretaceous in both Europe and North America113,114. The feeding apparatus of both clades is known to have evolved over the ensuing tens of millions of years, as did their presumed ecological roles58. Ceratopsids originated in the early to middle Campanian (Late Cretaceous) in North America, which coincides with the first appearance of centrosaurines115,116,117. Chasmosaurines did not appear until the middle Campanian in North America25,118, although their ghost lineage presumably extended back to the early Campanian. The first known co-occurrence of centrosaurines and chasmosaurines dates to the middle Campanian25. The earliest hadrosaurines are early Campanian in age119,120, and the first lambeosaurines date to the late Santonian/early Campanian121, both from North America. They may have co-occurred as early as the middle Campanian111,122. The earliest known assemblage of ankylosaurs, ceratopsids, and hadrosaurids is from the upper Santonian Foremost Formation of Alberta123,124,125.

Following the deposition of the DPF, the predictable community structure noted here continued essentially intact. The same suite of ankylosaurids, nodosaurids, centrosaurines, chasmosaurines, hadrosaurines, and lambeosaurines was present throughout the Kirtlandian, represented primarily by deposits of the uppermost Fruitland and Kirtland formations in New Mexico126,127 (Table 4). Notably, the enormous (ca. 70,000 kg) sauropod Alamosaurus sanjuanensis also appeared at this time128, possibly an immigrant from South America129, but its ecological relationship to the other megaherbivores is unclear.

This community structure continued into the Edmontonian, seen in the lower deposits (uppermost Campanian) of the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, where the same typical suite of megaherbivores persisted (Table 4). Megaherbivore diversity appears to wane higher in section, but this is at least partly due to taphonomic biases in the Carbon and Whitemud members130. Nonetheless, the loss of both centrosaurines and hadrosaurines around this time (ca. 68 Ma) appears genuine, as these taxa do not postdate this time elsewhere in North America25. Interestingly, Brown and Henderson131 demonstrated that the chasmosaurine Regaliceratops peterhewsi was morphologically convergent on the centrosaurine cranial plan, and it is possible that it filled not only a similar behavioural role to the vacated centrosaurines, but a similar ecological role as well. Although the lower jaws of R. peterhewsi are unknown, those of other triceratopsin chasmosaurines that radiated at this time are distinctly longer and lower than those of other chasmosaurines, with taller coronoid processes132,133. This new configuration resulted in higher stress production in the lower jaw, but the ecological ramifications that followed are unclear.

The depauperate nature of the megaherbivore fauna of the Lancian (uppermost Maastrichtian) in Laramidia is well documented134,135,136; centrosaurines and lambeosaurines are definitively absent (although lambeosaurines are known to have survived elsewhere121). Some of the remaining groups likewise appear to be locally extirpated from certain well-sampled localities (e.g., nodosaurids from the Hell Creek Formation, Montana; hadrosaurines from the Scollard Formation, Alberta) (Table 4), but this phenomenon may reflect habitat preferences or local sampling biases as opposed to genuine declines in numbers. The regional loss of species richness and beta diversity preceding the end-Cretaceous extinction is causally ambiguous, but plausibly attributed to the reestablishment of gene flow following the regression of the Western Interior Seaway the concomitant availability of larger habitats, and overall climate equability137,138,139. These larger habitats also fostered larger body sizes among herbivores (e.g., Triceratops spp., Edmontosaurus annectens, Ankylosaurus magniventris) and their predators (e.g., Tyrannosaurus rex). Body size correlates positively with dietary breadth among herbivores5, and thus the corresponding reduction in niche availability may have compounded the deleterious effects of increased gene flow on species diversity.

Implications for the structuring of Late Cretaceous ecosystems

The DPF megaherbivore community appears to have been stable for the ~1.5 Myr deposition of the formation, evidenced by the continuous presence of ankylosaurids and nodosaurids (the latter are known from high in section, based on microsite material140), centrosaurines and chasmosaurines, and hadrosaurines and lambeosaurines. It was partly on this basis that Brinkman et al.141 and Mallon et al.29 described the fossil assemblage of the DPF as a chronofauna, defined as “a geographically restricted, natural assemblage of interacting animal populations that has maintained its basic structure over a geologically significant period of time”142. In fact, the same could be said for the entire Campanian-Maastrichtian vertebrate fossil assemblage of Laramidia143, which, in addition to the above taxa, supported the same predictable suite of fishes, lizards, snakes, turtles, champsosaurs, crocodilians, small ornithischians and theropods, and tyrannosaurids12,135,144. Olson142 linked chronofaunal persistence to stable environmental conditions, yet the Campanian-Maastrichtian of Laramidia was anything but stable, having witnessed extended periods of orogenic activity138, frequent forest fires145, and climatic fluctuations that resulted in changes to leaf physiognomy89 and reptile diversity146,147, among others. It may be that the ecological relationships examined here lent structure to the Late Cretaceous megaherbivore chronofauna, enabling its persistence148.

The regulating effects of competition on community structure may have further promoted faunal endemism during the Late Cretaceous (especially during the Campanian) of the North American western interior. Several authors12,13,149 have noted the existence of distinct faunal provinces across the ancient landscape of Laramidia (but see Lucas et al.150), but the associated diversity drivers remain elusive. Among those implicated are habitat fragmentation due to sea-level rise or orogeny, and floral zonation due to climatic gradients12,135,138,149,151. Longrich152 further argued for a role for competitive exclusion in explaining Laramidian provincialism, whereby species were prevented from immigrating into already established communities due to competition from the native fauna, leading to community isolation and increased beta diversity. He noted two predictions that follow from the competition hypothesis: (1) coordinated replacement in the fossil record, as older species are replaced by newer ones, and (2) geographic range expansion of species during times of reduced beta diversity (and thus, reduced competition). Prediction 1 is borne out by the present study, and is further supported by the demonstration of ecomorphological overlap between closely related species. Prediction 2 is likewise upheld by recent work, as discussed above. Thus, competition not only served to structure local megaherbivore communities, but also may have driven increases in beta diversity across the face of the Late Cretaceous western interior of North America.

Megaherbivore ecology.

Although both mammalian and dinosaurian megaherbivore communities appear to be shaped by bottom-up processes (i.e., limiting resources), this is hardly a foregone conclusion. Dinosaurs are not mammals, and the physiologies of the non-avian dinosaurs in particular likely ran the gamut from poikilothermy to homeothermy153. Thus, the mass-specific nutritional requirements of the megaherbivorous dinosaurs were, in all likelihood, less than those of their modern mammalian counterparts52. Further, the large body sizes of many of the carnivorous theropods, surpassing those of most modern carnivores (Fig. 1), means that even the megaherbivorous dinosaurs were not necessarily safe from top-down predation. However, the fact that predation did not entirely alleviate competitive interactions between the megaherbivores suggests that theropods may have favoured feeding on small or young individuals11,67,154. Finally, elevated atmospheric CO2 levels during the Late Cretaceous would have enhanced terrestrial primary productivity155,156,157,158, potentially reducing competitive strain among herbivores. In light of these considerations, the finding that both megaherbivorous mammals and dinosaurs were similarly resource-limited, despite their different evolutionary histories, physiologies, and exposure to otherwise very different conditions, is remarkable. It underscores the importance of resource availability in sustaining large herbivore diversity, independent of phylogeny.

Conclusions

The model presented here is among the first to find quantitative support for competition-mediated megaherbivore community structure among dinosaurs. Like any model, it is only as good as the premises on which it is built, and its applicability both within and beyond the DPF is subject to testing with additional fossil discoveries. As the basic tenets of competitive exclusion are not in imminent danger of refutation, the model proposed here can be falsified by demonstrating (1) that megaherbivore species overlapped significantly in morphospace, and (2) that this overlap involved common taxa and persisted over time. Precisely what length of time is required to refute this model is difficult to say, but 300–600 Kyr seems reasonable, which is the average temporal range of a megaherbivore species within the DPF29. Where average species ranges are longer (e.g., 1.5–2 Myr in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation130), the amount of temporal overlap required to refute the proposed model would be correspondingly longer.

Further predictions might be teased from the present model. If megaherbivore niches were truly broader as a result of increased body size during the Maastrichtian (see Discussion), this might be reflected in the tooth wear or isotopic signals of Ankylosaurus magniventris, Edmontosaurus annectens, and Triceratops spp., particularly when compared to their Campanian predecessors. Exploratory work along these lines is certainly warranted.

Importantly, this study is based entirely on adult fossil material; immature individuals were excluded from this analysis (and those that preceded it) due to their rarity and incompleteness. Nonetheless, the young of megaherbivorous dinosaur species would have played an important role in their respective ecosystems, and may have been important competitors for the small herbivore species159,160. Follow-up studies on ontogenetic niche shifts in the megaherbivorous species, and their competitive likelihood at small body sizes, would further help to extend the present model.

It is worth stressing that this study does not attempt to explain how those ecomorphological differences arose among would-be competitors; it shows only that they arose, and explores the ecological implications that followed. Whether those differences between closely related (e.g., confamilial) taxa resulted from ecological displacement is worthy of investigation, but is beyond the scope of the present study. To this end, it would be interesting to investigate whether the feeding apparatuses of the clades examined here became more dissimilar to each other through their evolutionary histories, potentially reflecting character displacement due to ecological competition. It may be further possible to test whether more closely related (i.e., more ecomorphologically similar) taxa are more likely to go extinct as a result of sympatry, bolstering the character displacement hypothesis. Megaherbivore coexistence was evidently not a major evolutionary driver of cranial ornamentation during the Late Cretaceous161, but its role in promoting ecomorphological disparity via competition cannot yet be discounted.

References

Tokeshi, M. Species Coexistence: Ecological and Evolutionary Perspectives (Blackwell Science, 1999).

Pradhan, N. M. B., Wegge, P., Moe, S. R. & Shrestha, A. K. Feeding ecology of two endangered sympatric megaherbivores: Asian elephant Elephas maximus and greater one-horned rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis in lowland Nepal. Wildl. Biol. 14, 147–154 (2008).

Landman, M., Schoeman, D. S. & Kerley, G. I. H. Shift in black rhinoceros diet in the presence of elephant: evidence for competition? PLOS ONE 8, e69771 (2013).

Owen-Smith, N., Cromsigt, J. P. G. M. & Arsenault, R. Megaherbivores, competition and coexistence within the large herbivore guild. In Conserving Africa’s Mega-diversity in the Anthropocene (eds Cromsigt, J. P. G. M., Archibald, S. & Owen-Smith, N.) 111–134 (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Owen-Smith, R. N. Megaherbivores: the Influence of Very Large Body Size on Ecology (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Van Valkenburgh, B. & Molnar, R. E. Dinosaurian and mammalian predators compared. Paleobiology 28, 527–543 (2002).

Currie, P. J. & Eberth, D. A. On gregarious behavior in Albertosaurus. Can. J. Earth Sci. 47, 1277–1289 (2010).

Lingham-Soliar, T., Broderick, T. & Ahmed, A. A. K. Closely associated theropod trackways from the Jurassic of Zimbabwe. Naturwissenschaften 90, 572–576 (2003).

McCrea, R. T. et al. A ‘terror of tyrannosaurs’: the first trackways of tyrannosaurids and evidence of gregariousness and pathology in Tyrannosauridae. PLOS ONE 9, e103613 (2014).

Jacobsen, A. R. Feeding behaviour of carnivorous dinosaurs as determined by tooth marks on dinosaur bones. Hist. Biol. 13, 17–26 (1998).

Hone, D. W. E. & Rauhut, O. W. M. Feeding behaviour and bone utilization by theropod dinosaurs. Lethaia 43, 232–244 (2010).

Lehman, T. M. Late Campanian dinosaur biogeography in the Western Interior of North America in Dinofest International: Proceedings of a Symposium Sponsored by Arizona State University (eds Wolberg, D. L., Stump E. & Rosenberg, G. D.) 223–240 (Academy of Natural Sciences, 1997).

Sampson, S. D. & Loewen, M. A. Unraveling a radiation: a review of the diversity, stratigraphic distribution, biogeography, and evolution of horned dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) in New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: the Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium (eds Ryan, M. J., Chinnery-Allgeier, B. J. & Eberth, D. A.) 405–427 (Indiana University Press, 2010).

Coe, M. J., Dilcher, D. L., Farlow, J. O., Jarzen, D. M. & Russell, D. A. Dinosaurs and land plants in The Origins of Angiosperms and their Biological Consequences (eds Friis, E. M., Chaloner, W. G. & Crane, P. R.) 225–258 (Cambridge University Press, 1987).

Farlow, J. O. A consideration of the trophic dynamics of a Late Cretaceous large‐dinosaur community (Oldman Formation). Ecology 57, 841–857 (1976).

Farlow, J. O., Dodson, P. & Chinsamy, A. Dinosaur biology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 26, 445–471 (1995).

Horner, J. R. & Makela, R. Nest of juveniles provides evidence of family structure among dinosaurs. Nature 282, 296–298 (1979).

Lockley, M. G., Young, B. H. & Carpenter, K. Hadrosaur locomotion and herding behavior: evidence from footprints in the Mesaverde Formation, Grand Mesa Coal Field, Colorado. Mountain Geol. 20, 5–14 (1983).

Eberth, D. A., Brinkman, D. B. & Barkas, V. A centrosaurine mega-bonebed from the Upper Cretaceous of southern Alberta: implications for behavior and death events in New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: the Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium (eds Ryan, M. J., Chinnery-Allgeier, B. J. & Eberth, D. A.) 495–508 (Indiana University Press, 2010).

Currie, P. J. Theropods, including birds in Dinosaur Provincial Park: a Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed (eds Currie, P. J. & Koppelhus, E. B.) 367–397 (Indiana University Press, 2005).

Gause, G. F. The Struggle for Existence (Williams & Wilkins Company, 1934).

Wainwright, P. C. & Reilly, S. M. (eds) Ecological Morphology: Integrative Organismal Biology (University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Hubbell, S. P. The Unified Neutral Theory of Species Abundance and Diversity (Princeton University Press, 2001).

Hutchinson, G. E. Concluding remarks. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 22, 415–427 (1957).

Fowler, D. W. Revised geochronology, correlation, and dinosaur stratigraphic ranges of the Santonian-Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) formations of the Western Interior of North America. PLOS ONE 12, e0188426 (2017).

Brown, C. M., Ryan, M. J. & Evans, D. C. A census of Canadian dinosaurs: more than a century of discovery in All Animals are Interesting: a Festschrift Celebrating the Career of Anthony P. Russell (eds Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P., Powell, G. L., Jamniczky, H. A., Bauer, A. M. & Theodor, J. M.) 151–209 (BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität, 2015).

Ryan, M. J. & Evans, D. C. Ornithischian dinosaurs in Dinosaur Provincial Park: a Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed (eds Currie, P. J. & Koppelhus, E. B.) 312–348 (Indiana University Press, 2005).

Currie, P. J. & Russell, D. A. The geographic and stratigraphic distribution of articulated and associated dinosaur remains in Dinosaur Provincial Park: a Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed (eds Currie, P. J. & Koppelhus, E. B.) 537–569 (Indiana University Press, 2005).

Mallon, J. C., Evans, D. C., Ryan, M. J. & Anderson, J. S. Megaherbivorous dinosaur turnover in the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 350, 124–138 (2012).

Mallon, J. C. Evolutionary palaeoecology of the megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Calgary, 2012).

Mallon, J. C., Evans, D. C., Ryan, M. J. & Anderson, J. S. Feeding height stratification among the herbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. BMC Ecol. 13, 14, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6785-13-14 (2013).

Mallon, J. C. & Anderson, J. S. Skull ecomorphology of megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. PLOS ONE 8, e67182 (2013).

Mallon, J. C. & Anderson, J. S. Implications of beak morphology for the evolutionary paleoecology of the megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 394, 29–41 (2014).

Mallon, J. C. & Anderson, J. S. The functional and palaeoecological implications of tooth morphology and wear for the megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. PLOS ONE 9, e98605 (2014).

Mallon, J. C. & Anderson, J. S. Jaw mechanics and evolutionary paleoecology of the megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. J. Vert. Paleontol. 35, e904323 (2015).

Peters, R. H. The Ecological Implications of Body Size (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

Campione, N. E. MASSTIMATE: body mass estimation equations for vertebrates. R package version 1.3, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MASSTIMATE (2016).

Campione, N. E. & Evans, D. C. A universal scaling relationship between body mass and proximal limb bone dimensions in quadrupedal terrestrial tetrapods. BMC Biol. 10, 60 (2012).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.4–6, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2018).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/ (2017).

Carrano, M. T., Janis, C. M. & Sepkoski, J. J. Jr. Hadrosaurs as ungulate parallels: lost lifestyles and deficient data. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 44, 237–261 (1999).

Button, D. J., Rayfield, E. J. & Barrett, P. M. Cranial biomechanics underpins high sauropod diversity in resource-poor environments. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20142114 (2014).

Legendre, P. & Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology (Elsevier Science, 1998).

Kendall, M. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 30, 81–89 (1938).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 9, http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm (2001).

Ostrom, J. H. A reconsideration of the paleoecology of hadrosaurian dinosaurs. Am. J. Sci. 262, 975–997 (1964).

Sampson, S. D. Dinosaur Odyssey: Fossil Threads in the Web of Life (University of California Press, 2009).

Sinclair, A. R. E. Does interspecific competition or predation shape the African ungulate community? J. Anim. Ecol. 54, 899–918 (1985).

Dobson, A. The ecology and epidemiology of rinderpest virus in Serengeti and Ngorongoro crater conservation area in Serengeti II: Research, Management and Conservation of an Ecosystem (eds Sinclair, A. R. E. & Arcese, P.) 485–505 (University of Chicago Press, 1995).

Fiorillo, A. R. Dental microwear patterns of the sauropod dinosaurs Camarasaurus and Diplodocus: evidence for resource partitioning in the Late Jurassic of North America. Hist. Biol. 13, 1–16 (1998).

Goswami, A., Flynnbae, J. J., Ranivoharimananac, L. & Wyss, A. R. Dental microwear in Triassic amniotes: implications for paleoecology and masticatory mechanics. J. Vert. Paleontol. 25, 320–329 (2005).

Farlow, J. O. Speculations about the diet and digestive physiology of herbivorous dinosaurs. Paleobiology 13, 60–72 (1987).

Eberth, D. A., Evans, D. C. & Lloyd, D. W. H. Occurrence and taphonomy of the first documented hadrosaurid bonebed from the Dinosaur Park Formation (Belly River Group, Campanian) at Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada in Hadrosaurs (eds Eberth, D. A. & Evans, D. C.) 502–523 (Indiana University Press, 2014).

Ullmann, P. V., Shaw, A., Nellermoe, R. & Lacovara, K. J. Taphonomy of the Standing Rock hadrosaur site, Corson County, South Dakota. Palaios 32, 779–796 (2017).

Arbour, V. M. & Mallon, J. C. Unusual cranial and postcranial anatomy in the archetypal ankylosaur Ankylosaurus magniventris. FACETS 2, 764–794 (2017).

Jones, C. G., Lawton, J. H. & Shachak, M. Organisms as ecosystem engineers. Oikos 69, 373–386 (1994).

Haynes, G. Elephants (and extinct relatives) as earth-movers and ecosystem engineers. Geomorphology 157, 99–107 (2012).

Ősi, A., Prondvai, E., Mallon, J. & Bodor, E. R. Diversity and convergences in the evolution of feeding adaptations in ankylosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia). Hist. Biol. 29, 539–570 (2017).

Fraser, D. & Theodor, J. M. Comparing ungulate dietary proxies using discriminant function analysis. J. Morphol. 272, 1513–1526 (2011).

Lauder, G. V. On the inference of function from structure in Functional Morphology in Vertebrate Paleontology (ed. Thomason, J. J.) 1–18 (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Dodson, P. Sedimentology and taphonomy of the Oldman Formation (Campanian), Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta (Canada). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 10, 21–74 (1971).

Brinkman, D. B., Ryan, M. J. & Eberth, D. A. The paleogeographic and stratigraphic distribution of ceratopsids (Ornithischia) in the upper Judith River Group of western Canada. Palaios 13, 160–169 (1998).

Butler, R. J. & Barrett, P. M. Palaeoenvironmental controls on the distribution of Cretaceous herbivorous dinosaurs. Naturwissenschaften 95, 1027–1032 (2008).

King, G. Reptiles and Herbivory (Chapman and Hall, 1996).

Vickaryous, M. K., Maryańska, T. & Weishampel, D. B. Ankylosauria in The Dinosauria, second edition (eds Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H.) 363–392 (University of California Press, 2004).

Bakker, R. T. The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and their Extinction (Zebra Books, 1986).

Hummel, J. & Clauss, M. Megaherbivores as pacemakers of carnivore diversity and biomass: distributing or sinking trophic energy? Evol. Ecol. Res. 10, 925–930 (2008).

Jarzen, D. M. Palynology of Dinosaur Provincial Park (Campanian) Alberta. Syllogeus 38, 1–69 (1982).

Braman, D. R. & Koppelhus, E. B. Campanian palynomorphs in Dinosaur Provincial Park: a Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed (eds Currie, P. J. & Koppelhus, E. B.) 101–130 (Indiana University Press, 2005).

Paul, G. S. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (Princeton University Press, 2010).

Molnar, R. E. & Clifford, H. T. An ankylosaurian cololite from the Lower Cretaceous of Queensland, Australia in The Armored Dinosaurs (ed. Carpenter, K.) 399–412 (Indiana University Press, 2001).

Benson, R. B. J. et al. Rates of dinosaur body mass evolution indicate 170 million years of sustained ecological innovation on the avian stem lineage. PLOS Biol. 12, e1001853 (2014).

Carpenter, K. Skeletal and dermal armor reconstructions of Euoplocephalus tutus (Ornithischia: Ankylosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous Oldman Formation of Alberta. Can. J. Earth Sci. 19, 689–697 (1982).

Carpenter, K. Ankylosauria in Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs (eds Currie, P. J. & Padian, K.) 16–20 (Academic Press, 1997).

Carpenter, K. Ankylosaurs in The Complete Dinosaur (eds Farlow, J. O. & Brett-Surman, M. K.) 307–316 (Indiana University Press, 1997).

Carpenter, K. Redescription of Ankylosaurus magniventris Brown 1908 (Ankylosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior of North America. Can. J. Earth Sci. 41, 961–986 (2004).

Carpenter, K. Ankylosaur systematics: example using Panoplosaurus and Edmontonia (Ankylosauria: Nodosauridae) in Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives (eds. Carpenter, K. & Currie, P. J.) 281–298 (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Vickaryous, M. K. New information on the cranial anatomy of Edmontonia rugosidens Gilmore, a Late Cretaceous nodosaurid dinosaur from Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta. J. Vert. Paleontol. 26, 1011–1013 (2006).

Lucas, P. W. Dental Functional Morphology: How Teeth Work (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Ostrom, J. H. A functional analysis of jaw mechanics in the dinosaur Triceratops. Postilla 88, 1–35 (1964).

Erickson, G. M. et al. Wear biomechanics in the slicing dentition of the giant horned dinosaur Triceratops. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500055 (2015).

Hummel, J. et al. In vitro digestibility of fern and gymnosperm foliage: implications for sauropod feeding ecology and diet selection. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 1015–1021 (2008).

Dodson, P. Comparative craniology of the Ceratopsia. Am. J. Sci. 293A, 200–234 (1993).

Dodson, P. The Horned Dinosaurs: a Natural History (Princeton University Press, 1996).

Dodson, P. Neoceratopsia in Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs (eds Currie, P. J. & Padian, K.) 473–478 (Academic Press, 1997).

Braman, D. pers. comm. (2012).

Mustoe, G. E. Coevolution of cycads and dinosaurs. Cycad Newsl. 30, 6–9 (2007).

Gee, C. T. Dietary options for the sauropod dinosaurs from an integrated botanical and paleobotanical perspective in Biology of the Sauropod Dinosaurs: Understanding the Life of Giants (eds Klein, N., Remes, K., Gee, C. T. & Sander, P. M.) 34–56 (Indiana University Press, 2010).

Upchurch, G. R. Jr. & Wolfe, J. A. Cretaceous vegetation of the Western Interior and adjacent regions of North America. Geol. Assoc. Can. Spec Pap. 39, 243–281 (1993).

Brinkman, D. B. Paleoecology of the Judith River Formation (Campanian) of Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada: evidence from vertebrate microfossil localities. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimat. Palaeoecol. 78, 37–54 (1990).

Bakker, R. T. Dinosaur feeding behaviour and the origin of flowering plants. Nature 274, 661–663 (1978).

Barrett, P. M. & Willis, K. J. Did dinosaurs invent flowers? Dinosaur-angiosperm coevolution revisited. Biol. Rev. 76, 411–447 (2001).

Butler, R. J., Barrett, P. M., Kenrick, P. & Penn, M. G. Diversity patterns amongst herbivorous dinosaurs and plants during the Cretaceous: implications for hypotheses of dinosaur/angiosperm coevolution. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 446–459 (2009).

Henderson, D. M. Skull shapes as indicators of niche partitioning by sympatric chasmosaurine and centrosaurine dinosaurs. In New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: the Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium (eds. Ryan, M. J., Chinnery-Allgeier, B. J. & Eberth, D. A.) 293–307 (Indiana University Press, 2010).

Nabavizadeh, A. & Weishampel, D. B. The predentary bone and its significance in the evolution of feeding mechanisms in ornithischian dinosaurs. Anat. Rec. 299, 1358–1388 (2016).

Brown, C. M., Evans, D. C., Campione, N. E., O’Brien, L. J. & Eberth, D. A. Evidence for taphonomic size bias in the Dinosaur Park Formation (Campanian, Alberta), a model Mesozoic terrestrial alluvial‐paralic system. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 372, 108–122 (2012).

Erickson, G. M. Incremental lines of von Ebner in dinosaurs and the assessment of tooth replacement rates using growth line counts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93, 14623–14627 (1996).

Currie, P. J., Koppelhus, E. B. & Muhammad, A. F. Stomach contents of a hadrosaur from the Dinosaur Park Formation (Campanian, Upper Cretaceous) of Alberta, Canada in Sixth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Short Papers (eds. Sun, A. & Wang, Y.) 111–114 (China Ocean Press, 1995).

Chin, K. & Gill, B. D. Dinosaurs, dung beetles, and conifers: participants in a Cretaceous food web. Palaios 11, 280–285 (1996).

Chin, K. The paleobiological implications of herbivorous dinosaur coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana: why eat wood? Palaios 22, 554–566 (2007).

Kräusel, R. D. Nahrung von Trachodon: Paläontol. Z. 4, 80 (1922).

Tweet, J. S., Chin, K., Braman, D. R. & Murphy, N. L. Probable gut contents within a specimen of Brachylophosaurus canadensis (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana. Palaios 23, 624–635 (2008).

Sander, P. M., Gee, C. T., Hummel, J. & Clauss, M. Mesozoic plants and dinosaur herbivory in Plants in Mesozoic Time: Morphological Innovations, Phylogeny, Ecosystems (ed. Gee, C. T.) 331–359 (Indiana University Press, 2010).

Chin, K., Feldmann, R. M. & Tashman, J. N. Consumption of crustaceans by megaherbivorous dinosaurs: dietary flexibility and dinosaur life history strategies. Sci. Rep. 7, 11163 (2017).

Dodson, P. Taxonomic implications of relative growth in lambeosaurine hadrosaurs. Syst. Biol. 24, 37–54 (1975).

Chapman, R. E. & Brett-Surman, M. K. Morphometric observations on hadrosaurid ornithopods in Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives (eds Carpenter, K. & Currie P. J.) 163–177 (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Solounias, N. & Semprebon, G. Advances in the reconstruction of ungulate ecomorphology with application to early fossil equids. Am. Mus. Novit. 3366, 1–49 (2002).

Sampson, S. D., Loewen, M. A., Roberts, E. M. & Getty, M. A. A new macrovertebrate assemblage from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of southern Utah. In At the Top of the Grand Staircase: the Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah (eds Titus, A. L. & Loewen, M. A.) 599–620 (Indiana University Press, 2013).

Trexler, D. Two Medicine Formation, Montana: geology and fauna in Mesozoic Vertebrate Life (eds Tanke, D. H. & Carpenter, K.) 298–309 (Indiana University Press, 2001).

Mallon, J. C., Ott, C. J., Larson, P. L., Luliano, E. & Evans, D. C. Spiclypeus shipporum gen. et sp. nov., a boldly audacious new chasmosaurine ceratopsid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Judith River Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Campanian) of Montana, USA. PLOS ONE 11, e0154218 (2016).

Weishampel, D. B. et al. Dinosaur distribution in The Dinosauria, second edition (eds Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H.) 517–606 (University of California Press, 2004).

Arbour, V. M. & Currie, P. J. Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 14, 385–444 (2016).

Barrett P. M. & Maidment, S. Wealden armoured dinosaurs in English Wealden Fossils (ed. Batten, D. J.) 391–406 (Palaeontological Association, 2011).

Carpenter, K., Bartlett, J., Bird, J. & Barrick, R. Ankylosaurs from the Price River Quarries, Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), east-central Utah. J. Vert. Paleontol. 28, 1089–1101 (2008).

Williamson, T. E. A new Late Cretaceous (early Campanian) vertebrate fauna from the Allison Member, Menefee Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. New Mex. Mus. Nat. Hist. Sci. Bull. 11, 51–59 (1997).

Loewen, M. A. et al. Ceratopsid dinosaurs from the Grand Staircase of southern Utah in At the Top of the Grand Staircase: the Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah (eds Titus, A. L. & Loewen, M. A.) 488–503 (Indiana University Press, 2013).

Brown, C. M. Long-horned Ceratopsidae from the Foremost Formation (Campanian) of southern Alberta. PeerJ 6, e4265 (2018).

Longrich, N. R. Judiceratops tigris, a new horned dinosaur from the middle Campanian Judith River Formation of Montana. Bull., Peabody Mus. Nat. Hist. 54, 51–65 (2013).

Gates, T. A., Horner, J. R., Hanna, R. R. & Nelson, C. R. New unadorned hadrosaurine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the Campanian of North America. J. Vert. Paleontol. 31, 798–811 (2011).

Xing, H., Mallon, J. C. & Currie, M. L. Supplementary cranial description of the types of Edmontosaurus regalis (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae), with comments on the phylogenetics and biogeography of Hadrosaurinae. PLOS ONE 12, e0175253 (2017).

Prieto-Marquez, A. Global historical biogeography of hadrosaurid dinosaurs. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 159, 503–525 (2010).

Gates, T. A., Jinnah, Z., Levitt, C. & Getty, M. A. New hadrosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) specimens from the lower-middle Campanian Wahweap Formation of southern Utah in Hadrosaurs (eds Eberth, D. A. & Evans, D. C.) 156–173 (Indiana University Press, 2014).

Russell, L. S. Fauna of the upper Milk River beds, southern Alberta. Trans. R. Soc. Can. Ser. 3(29), 115–127 (1935).

Russell, L. S. & Landes, R. W. Geology of the southern Alberta plains. Geol. Surv. Can., Mem. 221, 1–223 (1940).

Baszio, S. Palaeo-ecology of dinosaur assemblages throughout the Late Cretaceous of South Alberta, Canada. Cour. Forsch. Inst. Senckenberg 196, 1–31 (1997).

Sullivan, R. M. & Lucas, S. G. The Kirtlandian land-vertebrate “age”–faunal composition, temporal position and biostratigraphic correlation in the nonmarine Upper Cretaceous of western North America. New Mex. Mus. Nat. Hist. Sci. Bull. 35, 7–29 (2006).

Arbour, V. M. et al. A new ankylosaurid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Kirtlandian) of New Mexico with implications for ankylosaurid diversity in the Upper Cretaceous of Western North America.”. PLOS ONE 9, e108804 (2014).

Fowler, D. W. & Sullivan, R. M. The first giant titanosaurian sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of North America. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 56, 685–690 (2011).

Tykoski, R. S. & Fiorillo, A. R. An articulated cervical series of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from Texas: new perspective on the relationships of North America’s last giant sauropod. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 15, 339–364 (2017).

Eberth, D. A. et al. Dinosaur biostratigraphy of the Edmonton Group (Upper Cretaceous), Alberta, Canada: evidence for climate influence. Can. J. Earth Sci. 50, 701–726 (2013).

Brown, C. M. & Henderson, D. M. A new horned dinosaur reveals convergent evolution in cranial ornamentation in Ceratopsidae. Curr. Biol. 25, 1641–1648 (2015).

Maiorino, L., Farle, A. A., Kotsakis, T., Teresi, L. & Piras, P. Variation in the shape and mechanical performance of the lower jaws in ceratopsid dinosaurs (Ornithischia, Ceratopsia). J. Anat. 227, 631–646 (2015).

Maiorino, L., Farke, A. A., Kotsakis, T. & Piras, P. Macroevolutionary patterns in cranial and lower jaw shape of ceratopsian dinosaurs (Dinosauria, Ornithischia): phylogeny, morphological integration, and evolutionary rates. Evol. Ecol. Res. 18, 123–167 (2017).

Russell, D. A. The gradual decline of the dinosaurs—fact or fallacy? Nature 307, 360–361 (1984).

Archibald, J. D. Dinosaur Extinction and the End of an Era: What the Fossils Say (Columbia University Press, 1996).

Brusatte, S. L., Butler, R. L., Prieto-Márquez, A. & Norell, M. A. Dinosaur morphological diversity and the end-Cretaceous extinction. Nat. Commun. 3, 804 (2012).

Vavrek, M. J. & Larsson, H. C. E. Low beta diversity of Maastrichtian dinosaurs of North America. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 107, 8265–8268 (2010).

Gates, T. A., Prieto-Márquez, A. & Zanno, L. E. Mountain building triggered Late Cretaceous North American megaherbivore dinosaur radiation. PLOS ONE 7, e42135 (2012).

Brusatte, S. L. et al. The extinction of the dinosaurs. Biol. Rev. 90, 628–642 (2015).

Brinkman, D. B. pers. comm. (2019)

Brinkman, D. B., Russell, A. P., Eberth, D. A. & Peng, J. Vertebrate palaeocommunities of the lower Judith River Group (Campanian) of southeastern Alberta, Canada, as interpreted from vertebrate microfossil assemblages. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 213, 295–313 (2004).

Olson, E. C. The evolution of a Permian vertebrate chronofauna. Evolution 6, 181–196 (1952).

Bakker, R. T. The Belly River Suite: final chronofauna of Mesozoic deep time in Dinosaur Park Symposium: Short papers, Abstracts, and Program (eds Braman, D. R., Therrien, F., Koppelhus, E. B. & Taylor, W.) 1–2 (Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, 2005).

Wing, S. L. & Sues, H. D. Mesozoic and early Cenozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems in Terrestrial Ecosystems through Time: Evolutionary Paleoecology of Terrestrial Plants and Animals (eds Behrensmeyer, A. K. et al.) 327–416 (University of Chicago Press, 1992).

Brown, S. A. E., Collinson, M. E. & Scott, A. C. Did fire play a role in formation of dinosaur-rich deposits? An example from the Late Cretaceous of Canada. Paleobiodivers. Paleoenviron. 93, 317–326 (2013).

Brinkman, D. B. & Eberth, D. A. Turtles of the Horseshoe Canyon and Scollard formations, further evidence for a biotic response to Late Cretaceous climate change. Fossil Turtle Res. 1, 11–18 (2006).

Larson, D. W., Brinkman, D. B. & Bell, P. R. Faunal assemblages from the upper Horseshoe Canyon Formation, an early Maastrichtian cool-climate assemblage from Alberta, with special reference to the Albertosaurus sarcophagus bonebed. Can. J. Earth Sci. 47, 1159–1181 (2010).

DiMichele, W. A. et al. Long-term stasis in ecological assemblages: evidence from the fossil record. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 285–322 (2004).

Gates, T. A. et al. Biogeography of terrestrial and freshwater vertebrates from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) Western Interior of North America. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 291, 371–387 (2010).

Lucas, S. G., Sullivan, R. M., Lichtig, A. J., Dalman, S. G. & Jasinski, S. E. Late Cretaceous dinosaur biogeography and endemism in the Western Interior Basin, North America: a critical re-evaluation. New Mex. Mus. Nat. Hist. Sci. Bull. 71, 195–213 (2016).

Horner, J. R., Varricchio, D. J. & Goodwin, M. B. Marine transgressions and the evolution of Cretaceous dinosaurs. Nature 358, 59 (1992).

Longrich, N. R. The horned dinosaurs Pentaceratops and Kosmoceratops from the upper Campanian of Alberta and implications for dinosaur biogeography. Cretaceous Res. 51, 292–308 (2014).

Grady, J. M., Enquist, B. J., Dettweiler-Robinson, E., Wright, N. A. & Smith, F. A. Evidence for mesothermy in dinosaurs. Science 344, 1268–1272 (2014).

Farlow, J. O. & Holtz, T. R. Jr. The fossil record of predation in dinosaurs. Paleontol. Soc. Pap. 8, 251–266 (2002).

Beerling, D. J. Modelling palaeophotosynthesis: Late Cretaceous to present. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. B 346, 421–432 (1994).

Briggs, J. C. Global biogeography. Devel. Palaeontol. Stratig. 14, 1–452 (1995).

Decherd, S. M. Primary productivity and forage quality of Ginkgo biloba in response to elevated carbon dioxide and oxygen – an experimental approach to mid-Mesozoic paleoecology (Ph.D. dissertation, North Carolina State University, 2006).

Gill, F. L., Hummel, J., Sharifi, A. R., Lee, A. P. & Lomax, B. H. Diets of giants: the nutritional value of sauropod diet during the Mesozoic. Palaeontology 61, 647–658 (2018).

Codron, D., Carbone, C., Müller, D. W. H. & Clauss, M. Ontogenetic niche shifts in dinosaurs influenced size, diversity and extinction in terrestrial vertebrates. Biol. Lett. 8, 620–623 (2012).

O’Gorman, E. J. & Hone, D. W. E. Body size distribution of the dinosaurs. PLOS ONE 7, e51925 (2012).

Knapp, A., Knell, R. J., Farke, A. A., Loewen, M. A. & Hone, D. W. E. Patterns of divergence in the morphology of ceratopsian dinosaurs: sympatry is not a driver of ornament evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20180312 (2018).

Swain, T. Angiosperm-reptile co-evolution in Morphology and Biology of Reptiles (eds Bellairs, A. d’A. & Cox, C. B.) 107–122 (Academic Press, 1976).

Nopcsa, F. Palaeontological notes on reptiles. Geol. Hungar., Ser. Palaeontol. 1, 1–84 (1928).

Russell, L. S. Edmontonia rugosidens (Gilmore), an armoured dinosaur from the Belly River Series of Alberta. Univ. Toronto Stud., Geol. Ser. 43, 1–28 (1940).

Haas, G. On the jaw musculature of ankylosaurs. Am. Mus. Novit. 2399, 1–11 (1969).

Maryańska, T. Ankylosauridae (Dinosauria) from Mongolia. Palaeontol. Pol. 37, 85–151 (1977).

Russell, D. A. A vanished world: the dinosaurs of western Canada. Natl. Mus. Can. Nat. Hist. Ser. 4, 1–142 (1977).

Krassilov, V. A. Changes of Mesozoic vegetation and the extinction of dinosaurs. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 34, 207–224 (1981).