Abstract

Interferon-tau (IFNT), serves as a signal to maintain the corpus luteum (CL) during early pregnancy in domestic ruminants. We investigated here whether IFNT directly affects the function of luteinized bovine granulosa cells (LGCs), a model for large-luteal cells. Recombinant ovine IFNT (roIFNT) induced the IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs; MX2, ISG15, and OAS1Y). IFNT induced a rapid and transient (15–45 min) phosphorylation of STAT1, while total STAT1 protein was higher only after 24 h. IFNT treatment elevated viable LGCs numbers and decreased dead/apoptotic cell counts. Consistent with these effects on cell viability, IFNT upregulated cell survival proteins (MCL1, BCL-xL, and XIAP) and reduced the levels of gamma-H2AX, cleaved caspase-3, and thrombospondin-2 (THBS2) implicated in apoptosis. Notably, IFNT reversed the actions of THBS1 on cell viability, XIAP, and cleaved caspase-3. Furthermore, roIFNT stimulated proangiogenic genes, including FGF2, PDGFB, and PDGFAR. Corroborating the in vitro observations, CL collected from day 18 pregnant cows comprised higher ISGs together with elevated FGF2, PDGFB, and XIAP, compared with CL derived from day 18 cyclic cows. This study reveals that IFNT activates diverse pathways in LGCs, promoting survival and blood vessel stabilization while suppressing cell death signals. These mechanisms might contribute to CL maintenance during early pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The corpus luteum (CL) plays a crucial role in the regulation of the reproductive cycle, fertility, and maintenance of pregnancy1. Progesterone secreted by the CL regulates uterine receptivity and promotes elongation, implantation, and survival of the growing embryo2,3,4,5,6. In a non-fertile cycle, prostaglandin F2alpha (PGF2a) secreted from the uterus, causes CL regression and terminates its progesterone production1,7. Our previous studies have highlighted the role of thrombospondins (THBSs) during luteolysis, both THBS1 and THBS2 were up-regulated by PGF2a administration, specifically, in mature, PGF2a-responsive CL but not during the refractory stage (before day 5 of the cycle)8. PGF2a also elevated THBS1 and THBS2 expression in vitro in luteal cell types8,9. Thrombospondins comprise a family of five conserved multidomain, large glycoproteins of which THBS1 and THBS2, are highly homologous, exhibiting similar structural and functional domains10,11,12.

Interferon tau (IFNT) is secreted from the mononuclear trophectoderm of the conceptus during the peri-implantation period and acts as the key signal for extending CL function during early pregnancy in domestic ruminants, a process known as maternal recognition of pregnancy (MRP)13,14,15. Consistent with this idea, administration of IFNT into the sheep uterine lumen or the systemic circulation during MRP extended the CL lifespan16,17,18. IFNT belongs to the type 1 IFN family of peptides, binds type-1 interferon cell-surface receptors (IFNAR1 and IFNAR2), and activates Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription–interferon regulatory factor (JAK–STAT–IRF) signaling resulting in the induction of a large number of classical interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs)19,20,21. The primary distinguishing feature between IFNT and most other type I IFNs is its unique, trophoblast-specific expression pattern ruminants. In cows, IFNT is secreted by the trophoblastic cells throughout days 10–24 of pregnancy14,22. The presence of elevated levels of ISGs in CL of pregnant animals suggested extra-uterine, endocrine effects of IFNT16,18,23,24. In agreement with the model of an endocrine action of IFNT acting directly on the CL during early pregnancy, we have previously demonstrated that recombinant ovine IFNT (roIFNT) enhanced luteal endothelial cell proliferation and suppressed a battery of luteolytic genes in luteal endothelial cells and CL slices25. The CL is a transient endocrine gland that contains multiple cell populations in which two progesterone-producing cells exist—large and small luteal cells1,26,27. Although the large luteal cells represent a minority of the luteal cell numbers, they are the cell type with the greatest luteal volume and are responsible for the majority of progesterone output from the CL27,28,29. Furthermore, unlike small luteal cells, large luteal cells produced progesterone in a LH-independent manner29,30,31, consistent with a key role for this cell type during pregnancy when circulating progesterone is elevated and GnRH and LH pulse frequencies are decreased32.

This study investigated the direct actions of IFNT on large luteal cells, utilizing luteinized granulosa cells (LGCs) as an in vitro model. In addition, we evaluated here CL of early pregnant cows (on day 18) to complement the in vitro data.

Results

IFNT induces STAT1 phosphorylation and ISGs in LGCs

In this study, cells were incubated with various concentrations of roIFNT (0.01–10 ng/mL), and the expression of classical ISGs was assessed to investigate whether IFNT directly affects LGCs. roIFNT dose-dependently, robustly, and markedly elevated the mRNA concentrations of MX2, ISG15, and OAS1Y in LGCs (Fig. 1a–c). Among these ISGs, MX2 exhibited the highest fold induction in response to IFNT, followed by ISG15 and OAS1Y (Fig. 1a–c). In addition, IFNT enhanced the STAT1 phosphorylation (Fig. 1d), at tyrosine 701 already 15 min after treatment. The greatest STAT1 phosphorylation was observed at 45 min after IFNT treatment with declining phosphorylation thereafter (Fig. 1d). The content of the total STAT1 protein remained unchanged during the short-term incubation (~2 h) with IFNT (Fig. 1d); however, total STAT1 protein increased during the prolonged incubation time (24–48 h; Fig. 1e). Furthermore, these cells readily expressed interferon-alpha receptor 1 (IFNAR1; data not shown).

IFNT stimulated STAT1 dependent type-1 interferon pathway in LGCs. (a–c) Cells were incubated for 24 h with either basal media (control) or varying concentrations of roIFNT (0.01–10 ng/mL). Cells were then harvested, and the mRNA expression of (A) MX2, (b) ISG15 and (C) OAS1Y were determined using qPCR. (d) Tyrosine phosphorylated STAT1 (p-STAT1) and (e) total STAT1 proteins were analyzed using specific antibodies in western blotting. Representative images of western blots are presented in the upper panels of D and E. Blots in (d) were cropped from different gels, blots in (e) were cropped from different parts of the same gels. Whole cell extracts from LGCs were incubated with IFNT (1 ng/mL) for different time points as indicated. Quantitative analysis of phospho-STAT1 levels were normalized to total STAT1 and total STAT1 was normalized to total MAPK (p44/42) protein. Asterisks indicate significant differences from either time 0 or basal media (control) or control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

IFNT enhances LGCs survival and positively regulates proangiogenic factors

Treatment with roIFNT (1 ng/mL) doubled viable LGCs numbers compared to the control (basal medium) based on the XTT assay (see Materials and Methods); Fig. 2a). Next, cells were stained with Annexin V–FITC and propidium iodide (PI) and were analyzed by flow cytometry. LGCs incubated for 48 h with 1 ng/mL of roIFNT (Fig. 2b,c) resulted in significantly fewer apoptotic and dead cells and greater numbers of live cells compared to control LGCs (Fig. 2b,c).

IFNT increased LGCs viability and reduced apoptosis. (a) Cells were assayed with XTT 48 h after treatment with 1 ng/mL of roIFNT. (b) Cells were treated with 1 ng/mL of roIFNT and analyzed using FACS with propidium iodide and Annexin V staining (representative plots). (c) Quantification of FACS results. Asterisk indicate significant (*P < 0.05) difference from cells treated in basal media (control).

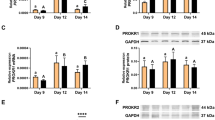

Besides IFNT-mediated antiapoptotic effects, we noted a time-dependent decline in proapoptotic THBS2 mRNA expression8,33, which was sharply reduced by treatment with roIFNT at 24 h remaining low at 36 h after treatment without altering THBS1 mRNA (Fig. 3). In addition, we assessed the effects of roIFNT on several proteins including myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL1) and B-cell lymphoma-extra-large (BCL-xL; anti apoptotic members of the BCL2 family), as well as the proapoptotic protein gamma H2A histone family, member X (gH2AX; Fig. 4a–c). There was a distinct temporal profile of induction for these proteins by IFNT. Treatment with roIFNT increased MCL1 within 24 h with a tendency for increased MCL1 protein at 36 h and numerically greater protein at 48 h. In contrast, there were no differences in BCLxL protein at 24 and 36 h after roIFNT treatment but there was a significant increase in compared with control (P < 0.01) at 48 h after roIFNT treatment. Compared with these two, gH2AX was inhibited by roIFNT (Fig. 4c) 36 and 48 h after treatment. In addition, we observed a marked treatment by time interaction for the gH2AX protein. Subsequently, we assessed whether roIFNT can alter apoptotic activities of THBS1described previously9,34,35. Treatment with THBS1 (250 ng/mL) reduced viable LGCs numbers (Fig. 5), corroborating previous results9. Moreover, treatment with roIFNT alone doubled viable LGCs numbers and decreased THBS1-mediated reduction in LGCs viability (Fig. 5a). These effects were also reflected in measuring X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP); THBS1 decreased XIAP protein levels, while roIFNT markedly increased its basal levels and those suppressed by THBS1 (Fig. 5c). Figure 5d presents additional evidence for the opposing effects of IFNT and THBS1. Levels of cleaved caspase-3 protein, which is a protein that is activated in the apoptotic cell, were significantly decreased by roIFNT and increased in THBS1-treated cells. In addition, treatment with THBS1 combined with roIFNT resulted in amounts of cleaved caspase 3 protein that were not different from roIFNT-treated cells but lower than either control or THBS1-treated cells (Fig. 5d).

Time-dependent effects of IFNT on pro- and antiapoptotic proteins. LGCs were incubated without (control) or with roIFNT (1 ng/mL) for 48 h, (a) MCL1, (b) BCL-xL, and (c) gH2AX protein levels were determined in cell extracts by western blotting and normalized relative to the abundance of total MAPK (p44/42). All blots expect MCL1 were cropped from different parts of the same gels. Results are presented as the means ± SEM from four independent experiments. (d) Representative images of the western blots for each antibody. Asterisks indicate significant differences from their respective controls (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

IFNT induces cell survival and counteracts THBS1 apoptotic actions. LGCs were treated with either with basal media (control), roIFNT (1 ng/mL), human recombinant THBS1 (250 ng/mL), or the combination of IFNT and THBS1 for 48 h. (a) The viable cell number, (b) Representative images of the western blots for each antibody, (c) XIAP and (d) cleaved caspase-3 proteins. Protein levels were determined in cell extracts by western blotting using specific antibodies and normalized relative to the abundance of total MAPK (p44/42). The results represent means ± SEM of four independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences from their respective controls (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Next, we evaluated the effect of IFNT on several proangiogenic factors expressed in LGCs, there was an increase of FGF2 (fibroblast growth factor-2) mRNA (Fig. 6a) and protein (Fig. 6b) in response to roIFNT. Treatment with roIFNT also markedly elevated mRNA concentrations for PDGFB and its receptor PDGFAR (Fig. 6c,d).

IFNT promotes proangiogenic factors in LGCs. LGCs were treated with either basal media (control) or roIFNT (1 and 10 ng/mL). (a,b) FGF2 mRNA and protein levels. (c) PDGFB and (d) PDGFAR mRNA expression. Asterisks indicate significant differences between roIFNT treatment and controls (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Comparison of gene expression in CL collected on day 18 CL from pregnant and non-pregnant cows

To determine whether genes that were stimulated in vitro by roIFNT were also upregulated during early pregnancy in vivo, CL were collected from pregnant cows on day 18 after AI, when IFNT concentrations are expected to be elevated14,22 or in cyclic non-inseminated cows on day 18 of the estrous cycle. Plasma progesterone was not different between pregnant (5.97 ± 0.79 ng/ml, n = 6) and cyclic (5.81 ± 1.10 ng/ml, n = 6) cows, confirming that CL were not undergoing regression at the time of collection. Figure 7a–c shows that day 18 pregnant CL exhibited greater mRNAs levels of MX2 (4.3-fold), ISG15 (4.2-fold), and STAT1 (3.3-fold) compared with non-pregnant cows on day 18, implying that IFNT was indeed elevated in pregnant animals. Besides elevated ISGs, FGF2 (3.4-fold), PDGFB (3.5-fold), and XIAP (1.5-fold) mRNAs were also higher in the CL derived from pregnant cows compared with day 18 cyclic cows (Fig. 7d–f).

Differential gene expression in pregnant and cyclic CL. The levels of (a) ISG15, (b) MX2, (c) STAT1, (d) FGF2, (e) PDGFB, and (f) XIAP mRNAs in day 18 CL from pregnant (P) and cyclic (C) cows. The total RNA was isolated from the tissue, and the mRNA expression were determined using qPCR. Asterisks indicate significant differences between pregnant and cyclic CL (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Discussion

The evidence provided by this study portray IFNT as an important survival factor for the large luteal-like cell. Treatment with IFNT increased viable LGCs numbers, reduced apoptotic cells, and increased prosurvival proteins such as XIAP, MCL1, and BCL-xL, while inhibiting antiapoptotic proteins, active caspase-3, and gH2AX. Notably, IFNT could also rescue THBS1-mediated apoptotic actions in LGCs. Concurrently with its prosurvival effects, IFNT stimulated proangiogenic factors –FGF2, PDGFB, and its receptor –PDGFAR. Although in vitro luteinized granulosa cells were repeatedly shown to be a reliable model for the bovine large luteal cells36,37,38,39,40, future studies employing CL -derived cells may ascertain these mechanisms in the early pregnant CL. In fact, CL derived from day 18 pregnant cows had elevated ISGs levels, along with higher XIAP, FGF2, and PDGFB compared with cyclic cows on day18, corroborating the in vitro data.

In domestic ruminants, IFNT initiates pregnancy recognition signaling, maintaining a favorable uterine environment for the successful establishment of pregnancy41. It is well defined that the primary antiluteolytic actions of IFNT are exerted on the endometrium to prevent the pulsatile release of the PGF2a42,43,44,45. Nevertheless, IFNT has also been detected in the uterine vein serum of ewes on days 15 and 16 of pregnancy, suggesting its presence in circulation17,46. Indeed, extra-uterine or endocrine effects of IFNT have been reported in domestic ruminants. Moreover, elevated ISGs were observed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, liver, mammary glands, lymphatic cells, and CL during early pregnancy16,24,47,48,49. Of these tissues, the CL occupies central significance because of its roles in establishing and maintenance of early pregnancy. More than the stimulation of ISGs, IFNT increased in vitro lymphatic bovine endothelial cell proliferation and capillary-like tube formation, suggesting its involvement in luteal lymph angiogenesis48. Recently it was reported that, IFNT increases IL8 in bovine luteal cells, suggesting that it can change immune microenvironment in the CL49. Furthermore, we have previously showed that IFNT activates the STAT1-dependent type-1 interferon pathway and stimulates ISGs in bovine luteal endothelial cells and CL slices25. The present study further supports this physiological concept, utilizing LGCs, we show that IFNT induces temporal STAT1 phosphorylation and the expression ISGs. Elevated ISGs were also observed in this study in CL of day 18 pregnant cows. Together, these observations provide strong evidence for IFNT responsiveness in CL and in luteal cells and for IFNT action in the CL during early pregnancy.

Apoptosis is convincingly implicated as a mechanism triggering CL demise in ruminant species50,51,52,53,54,55. Conversely, CL maintenance requires the suppression of apoptotic mechanisms and augmentation of survival signals55. Thus, a delicate balance between survival and apoptotic factors determine luteal cell fate. The BCL2 family proteins comprise a network that regulates intrinsic survival/apoptotic responses56 and contains anti- and proapoptotic proteins. There are BCL2 homologs that promote cell survival such as BCL2, BCxL, and MCL1. The proapoptotic BCL2 family members57 contain BH1 to BH4 domains which interact with antiapoptotic BCL2 homologs, preventing mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. XIAP is another major antiapoptotitc protein, which can directly bind and inhibit caspase 9 and the active effector protein caspase-358,59. BCL-xL and XIAP proteins are elevated in the sheep CL on days 12–16 of pregnancy compared with cyclic CL on the same days55. Likewise, we observed in this study that day 18 pregnant bovine CL had higher levels of XIAP than cyclic cows. Furthermore, the endocrine delivery of IFNT to cyclic ewes on day 10 was also found to elevate the mRNA levels of cell survival genes, such as BCL-xL and XIAP, compared with ewes treated with a vehicle only23. Thus, findings of this study demonstrating that IFNT enhanced the levels of MCL1, BCL-xL, and XIAP proteins but decreased cleaved caspase-3, are physiologically meaningful. Another critical apoptotic marker that was effectively suppressed by IFNT was gH2AX, a phosphorylated form of histone H2AX that can function as a sensitive marker for double-strand breaks, and it is highly correlated with the induction of apoptosis60,61.

This study also provides evidence demonstrating the ability of IFNT to reverse the known apoptotic actions of THBS1 on viable LGCs numbers, XIAP, and cleaved caspase-3. Previously we reported that IFNT downregulated THBS1 in bovine CL slices and luteal endothelial cells in vitro25. This study shows that IFNT markedly abolished in LGCs the expression of another THBS member - THBS2, highly expressed in these cells9. These findings are consistent with THBS1, THBS2 and their receptors being significantly downregulated in the CL for the whole duration of the bovine pregnancy62.

We observed that FGF2 was elevated by IFNT in vitro (Fig. 7a) and in early pregnant CL (Fig. 8d). FGF2 plays a vital role in supporting luteal angiogenesis and cell survival in vivo63 and in vitro64,65. Besides their direct antiangiogenic, proapoptotic effects, THBS1 and THBS2 were shown to sequester FGF2 and impair its biological activities (proliferation, survival and migration)8,9,11,66,67. Hence, the fact that IFNT suppressed THBS2 is expected to further augment the biological functions of FGF2, whose levels were induced in vitro and during early pregnancy. THBS1 and THBS2 have similar expression profiles in response to PGF2a and analogous biological functions, yet THBS2 is understudied in CL and it requires future studies.

Illustrative summary depicting IFNT actions balancing life and death of bovine LGCs. IFNT elevates viable LGCs numbers, reduces apoptotic cells, and increases prosurvival proteins including XIAP, MCL1, and BCL-xL. Concurrently with its prosurvival effects, IFNT stimulates proangiogenic factors—FGF2, PDGFB. Conversely, antiapoptotic factors, active caspase-3, THBS2 and gH2AX are inhibited by IFNT. These findings portray IFNT as a prominent luteal survival factor.

Another class of proangiogenic factors is the PDGF–PDGFR axis. In particular, PDGFB is involved in attracting pericytes to new vessels during angiogenesis, which are crucial for the stabilization and maturation of blood vessels68. In luteal endothelial cell network established in vitro, the inhibition of PDGF signaling markedly decreased their formation and sprouting69. Corroborating this notion, this study revealed that PDGFB and PDGFAR were stimulated by IFNT in LGCs and elevated PDGFB was also observed in the CL of day 18 pregnant cows.

In summary, this study establishes that IFNT directly promotes LGCs survival, it also contributes to cell health by counteracting THBSs-mediated apoptotic events. Furthermore, IFNT enhanced the production by LGCs of factors involved in luteal vasculature growth and stabilization. Previously we reported that IFNT also enhanced the survival of luteal endothelial cells and suppressed luteolytic genes in these cells and CL slices25. The actions of IFNT exerted on both luteal steroidogenic and endothelial cells might underline the mechanisms used by this pregnancy recognition signal in the CL to maintain its function during early pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of LGCs

We collected ovaries bearing large follicles (>10 mm in diameter) from a local slaughterhouse, as described previously7,60. Only follicles containing at least 4 million granulosa cells were included in these experiments. Granulosa cells were enzymatically dispersed by using a combination of collagenase I (5000 U), hyaluronidase III (1440 U), and deoxyribonuclease I (390 U; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F-12 containing 1% l-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel). Next, isolated granulosa cells were seeded for overnight incubation in DMEM/F-12 containing 3% fetal calf serum (FCS). The next day, media were replaced with luteinization media containing FCS (1%), insulin (2 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and forskolin (10 μM; Sigma-Aldrich). On day 6 of culture, the cells were washed with PBS and kept for 3–5 h adaptation period in DMEM/F-12 media containing1% FCS. Then cells were incubated for the times indicated in the legends either with basal media (media containing 1% FCS) or with roIFNT (0.01–10 ng/mL; a generous gift from Prof. Fuller W. Bazer, Texas A&M University) or recombinant human THBS1 (rhTHBS1; 250 ng/mL; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) alone or with the combination of rhTHBS1 and roIFNT. At the end of the incubation period, cells were collected for either total RNA extraction or protein for protein analyses, or for flow cytometry as described below.

Experimental procedures with animals and synchronization

The experiment was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations at the Experimental Station Hildegard Georgina Von Pritzelwiltz, located in Londrina, PR, Brazil. The Animal Research Ethics Committee of Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz” (ESALQ)/University of São Paulo approved all procedures involving cows in this study (Protocol #2018.5.1252.11.5).

Non-lactating Bos indicus cows (n = 35) were submitted to a fixed-time AI FTAI protocol GnRH-E2 based. On the day of insemination (Day 0) cows were assigned to the following treatments: Artificial insemination group (n = 20) vs. synchronized non-inseminated group (cyclic; n = 10). Cows from the AI group were inseminated using frozen/thawed semen from two high fertility Aberdeen Angus bulls (Alta Genetics, Uberaba, Brazil). On day 17 after AI and one day before CL collection, blood samples were collected by puncture of the coccygeal vein into evacuated 10 mL tubes containing sodium heparin (Vacutainer, Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Immediately after collection, the tubes were placed on ice and kept refrigerated until processing. Blood samples were centrifuged at 1,700 × g for 15 min and aliquots of plasma were frozen and stored in duplicates at −20 °C until assayed for progesterone. On Day 18 all cows were slaughtered and each horn was flushed using 10 mL of sterile saline solution in the AI group to assure the presence of an embryo. Pregnancy was confirmed by identification of an elongated embryo in uterine flushes and the presence of a functional CL was confirmed by measuring plasma progesterone using a commercial kit (CT Progesterone, MP Biomedicals LLC, Solon, OH, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The CL were collected in cryotubes and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction from six cows in each pregnant (P) and cyclic (C) groups.

Western blot analyses

Proteins were extracted with a sample buffer, separated by 7.5–12.0% SDS–PAGE, and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, as reported previously8. Membranes were blocked for 1 h in TBST (20 mmol/L Tris, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20; pH 7.6) containing 3% BSA or 5% low-fat milk, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following antibodies: goat polyclonal phosphorylated STAT1 (TYR701; 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany); goat polyclonal STAT1 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); rabbit anti-FGF2 antiserum (1:10 00; kindly provided by D. Schams, The Technical University of Munich), rabbit anti-MCL1 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), rabbit anti-gH2AX (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-XIAP (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), BCL-xL (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit anti-p44/42 total mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; 1:50,000; Sigma-Aldrich). The membranes were then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 h at room temperature. A chemiluminescent signal was generated with the SuperSignal Detection Kit for horseradish peroxidase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the signal was captured with ImageQuant LAS 500 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA). The protein bands were analyzed using Gel-Pro 32 Software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and the signal of anti-total MAPK (p44/42) antibody was used to correct for protein loading.

Determination of viable cell numbers

We estimated the viable cell numbers as described previously9, using the XTT Kit (Biological Industries), which measures the reduction of a tetrazolium component by the mitochondria of viable cells. On the day of measurement, XTT was added to the culture media per the manufacturer’s instructions. Plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 3–5 h. Afterwards, the absorbance was read at 450 nm (reference absorbance, 630 nm).

Analysis of cell viability/apoptosis by flow cytometry

We determined the cell viability/apoptosis using the Annexin V–FITC (PE) and PI double-staining apoptosis using the MEBCYTO Apoptosis Kit (Medical and Biological, Woburn, MA). After 48 h of incubation with 1 ng/mL of roIFNT or control media, cells were trypsinized and washed two times with PBS. Then, cells were centrifuged and suspended in 500 μL of binding buffer, after which 5 μL of Annexin V–FITC and PI staining solution were added and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Next, the mixture was analyzed by flow cytometer (FACS) BD FACSCalibur™ (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) within 30 min. Finally, the number of apoptotic cells was defined as the sum of the Annexin V–FITC+/PI− cells and Annexin V–FITC+/PI+ cells.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

The total RNA was isolated from the CL tissue/cells using Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) per the manufacturer’s instructions. As described previously, the total RNA was reverse-transcribed and quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) was performed using the LightCycler 96 System (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) with Platinum SYBR Green (SuperMix, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)25. Table 1 lists the sequences of primers used for quantitative qPCR. All primers were designed to have single-product melting curves, as well as consistent amplification efficiencies between 1.8 and 2.270,71. In addition, all amplicons were verified by sequencing. To select the most stable housekeeping gene, we applied the NormFinder algorithm; we selected GAPDH as a housekeeping gene, as described previously25,71.Furthermore, the threshold cycle number (Ct) was used to quantify the relative abundance of the gene; arbitrary units were calculated as 2−ΔCt = 2−(Ct target gene − Ct housekeeping gene)72.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 6.01 Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Data are presented as means ± SEM. In vitro experiments comprised, at least, three independent repeats; each repeat constituted cells obtained from different follicles (one follicle/cow). Data were analyzed by either Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni’s post-hoc multiple comparison test, when indicated. In this study, differences were considered as significant equal or below P < 0.05. Asterisks or different letters represent statistical significant differences (P < 0.05).

References

Niswender, G. D., Juengel, J. L., Silva, P. J., Rollyson, M. K. & McIntush, E. W. Mechanisms controlling the function and life span of the corpus luteum. Physiol Rev 80, 1–29 (2000).

Forde, N. et al. Progesterone-regulated changes in endometrial gene expression contribute to advanced conceptus development in cattle. Biol Reprod 81, 784–794 (2009).

Satterfield, M. C., Bazer, F. W. & Spencer, T. E. Progesterone regulation of preimplantation conceptus growth and galectin 15 (LGALS15) in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 75, 289–296 (2006).

Forde, N. et al. Effects of low progesterone on the endometrial transcriptome in cattle. Biol Reprod 87, 124 (2012).

Mullen, M. P. et al. Proteomic characterization of histotroph during the preimplantation phase of the estrous cycle in cattle. J Proteome Res 11, 3004–3018 (2012).

Wiltbank, M. C. et al. Physiological and practical effects of progesterone on reproduction in dairy cattle. Animal 8(Suppl 1), 70–81 (2014).

McCracken, J. A., Custer, E. E. & Lamsa, J. C. Luteolysis: a neuroendocrine-mediated event. Physiol Rev 79, 263–323 (1999).

Zalman, Y. et al. Regulation of angiogenesis-related prostaglandin f2alpha-induced genes in the bovine corpus luteum. Biol Reprod 86, 92 (2012).

Farberov, S. & Meidan, R. Functions and transcriptional regulation of thrombospondins and their interrelationship with fibroblast growth factor-2 in bovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod 91, 58 (2014).

Adams, J. C. & Lawler, J. The thrombospondins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3, a009712 (2011).

Colombo, G. et al. Non-peptidic thrombospondin-1 mimics as fibroblast growth factor-2 inhibitors: an integrated strategy for the development of new antiangiogenic compounds. J Biol Chem 285, 8733–8742 (2010).

Rusnati, M., Urbinati, C., Bonifacio, S., Presta, M. & Taraboletti, G. Thrombospondin-1 as a Paradigm for the Development of Antiangiogenic Agents Endowed with Multiple Mechanisms of Action. Pharmaceuticals 3, 1241 (2010).

Hansen, T. R., Sinedino, L. D. P. & Spencer, T. E. Paracrine and endocrine actions of interferon tau (IFNT). Reproduction 154, F45–F59 (2017).

Roberts, R. M., Ealy, A. D., Alexenko, A. P., Han, C. S. & Ezashi, T. Trophoblast interferons. Placenta 20, 259–264 (1999).

Bazer, F. W. Mediators of maternal recognition of pregnancy in mammals. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 199, 373–384 (1992).

Oliveira, J. F. et al. Expression of interferon (IFN)-stimulated genes in extrauterine tissues during early pregnancy in sheep is the consequence of endocrine IFN-tau release from the uterine vein. Endocrinology 149, 1252–1259 (2008).

Bott, R. C. et al. Uterine vein infusion of interferon tau (IFNT) extends luteal life span in ewes. Biol Reprod 82, 725–735 (2010).

Romero, J. J. et al. Pregnancy-associated genes contribute to antiluteolytic mechanisms in ovine corpus luteum. Physiol Genomics 45, 1095–1108 (2013).

Stewart, M. D. et al. Roles of Stat1, Stat2, and interferon regulatory factor-9 (IRF-9) in interferon tau regulation of IRF-1. Biol Reprod 66, 393–400 (2002).

Binelli, M. et al. Bovine interferon-tau stimulates the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway in bovine endometrial epithelial cells. Biol Reprod 64, 654–665 (2001).

Choi, Y. et al. Interferon regulatory factor-two restricts expression of interferon-stimulated genes to the endometrial stroma and glandular epithelium of the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 65, 1038–1049 (2001).

Hirayama, H. et al. Enhancement of maternal recognition of pregnancy with parthenogenetic embryos in bovine embryo transfer. Theriogenology 81, 1108–1115 (2014).

Antoniazzi, A. Q. et al. Endocrine delivery of interferon tau protects the corpus luteum from prostaglandin F2 alpha-induced luteolysis in ewes. Biol Reprod 88, 144 (2013).

Yang, L. et al. Up-regulation of expression of interferon-stimulated gene 15 in the bovine corpus luteum during early pregnancy. J Dairy Sci 93, 1000–1011 (2010).

Basavaraja, R. et al. Interferon-tau promotes luteal endothelial cell survival and inhibits specific luteolytic genes in bovine corpus luteum. Reproduction 154, 559–568 (2017).

Smith, G. W. & Meidan, R. Ever-changing cell interactions during the life span of the corpus luteum: relevance to luteal regression. Reprod Biol 14, 75–82 (2014).

O’Shea, J. D., Rodgers, R. J. & D’Occhio, M. J. Cellular composition of the cyclic corpus luteum of the cow. J Reprod Fertil 85, 483–487 (1989).

Milvae, R. A. & Hansel, W. Prostacyclin, prostaglandin F2 alpha and progesterone production by bovine luteal cells during the estrous cycle. Biol Reprod 29, 1063–1068 (1983).

Meidan, R., Girsh, E., Blum, O. & Aberdam, E. In vitro differentiation of bovine theca and granulosa cells into small and large luteal-like cells: morphological and functional characteristics. Biol Reprod 43, 913–921 (1990).

Mamluk, R., Chen, D., Greber, Y., Davis, J. S. & Meidan, R. Characterization of messenger ribonucleic acid expression for prostaglandin F2 alpha and luteinizing hormone receptors in various bovine luteal cell types. Biol Reprod 58, 849–856 (1998).

Alila, H. W., Corradino, R. A. & Hansel, W. Differential effects of luteinizing hormone on intracellular free Ca2+ in small and large bovine luteal cells. Endocrinology 124, 2314–2320 (1989).

He, W. et al. Hypothalamic effects of progesterone on regulation of the pulsatile and surge release of luteinising hormone in female rats. Sci Rep 7, 8096 (2017).

Mondal, M. et al. Deciphering the luteal transcriptome: potential mechanisms mediating stage-specific luteolytic response of the corpus luteum to prostaglandin F(2)alpha. Physiol Genomics 43, 447–456 (2011).

Farberov, S. & Meidan, R. Thrombospondin-1 Affects Bovine Luteal Function via Transforming Growth Factor-Beta1-Dependent and Independent Actions. Biol Reprod 94, 25 (2016).

Farberov, S., Basavaraja, R. & Meidan, R. Thrombospondin-1 at the crossroads of corpus luteum fate decisions. Reproduction (2018).

Mohammed, B. T., Sontakke, S. D., Ioannidis, J., Duncan, W. C. & Donadeu, F. X. The Adequate Corpus Luteum: miR-96 Promotes Luteal Cell Survival and Progesterone Production. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102, 2188–2198 (2017).

Wu, Y. L. & Wiltbank, M. C. Transcriptional regulation of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene changes from protein kinase (PK) A- to PKC-dependence after luteinization of granulosa cells. Biol Reprod 66, 1505–1514 (2002).

Baufeld, A. & Vanselow, J. Increasing cell plating density mimics an early post-LH stage in cultured bovine granulosa cells. Cell Tissue Res 354, 869–880 (2013).

Sahmi, F. et al. Factors regulating the bovine, caprine, rat and human ovarian aromatase promoters in a bovine granulosa cell model. Gen Comp Endocrinol 200, 10–17 (2014).

Schams, D., Kosmann, M., Berisha, B., Amselgruber, W. M. & Miyamoto, A. Stimulatory and synergistic effects of luteinising hormone and insulin like growth factor 1 on the secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor and progesterone of cultured bovine granulosa cells. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 109, 155–162 (2001).

Bazer, F. W., Spencer, T. E., Johnson, G. A. & Burghardt, R. C. Uterine receptivity to implantation of blastocysts in mammals. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 3, 745–767 (2011).

Mann, G. E. & Lamming, G. E. Progesterone inhibition of the development of the luteolytic signal in cows. J Reprod Fertil 104, 1–5 (1995).

Spencer, T. E., Ott, T. L. & Bazer, F. W. Tau-Interferon: pregnancy recognition signal in ruminants. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 213, 215–229 (1996).

Meyer, M. D. et al. Extension of corpus luteum lifespan and reduction of uterine secretion of prostaglandin F2 alpha of cows in response to recombinant interferon-tau. J Dairy Sci 78, 1921–1931 (1995).

Thatcher, W. W. et al. Antiluteolytic effects of bovine trophoblast protein-1. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 37, 91–99 (1989).

Romero, J. J. et al. Temporal Release, Paracrine and Endocrine Actions of Ovine Conceptus-Derived Interferon-Tau During Early Pregnancy. Biol Reprod 93, 146 (2015).

Matsuyama, S., Kojima, T., Kato, S. & Kimura, K. Relationship between quantity of IFNT estimated by IFN-stimulated gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and bovine embryonic mortality after AI or ET. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 10, 21 (2012).

Nitta, A. et al. Possible involvement of IFNT in lymphangiogenesis in the corpus luteum during the maternal recognition period in the cow. Reproduction 142, 879–892 (2011).

Shirasuna, K. et al. Possible role of interferon tau on the bovine corpus luteum and neutrophils during the early pregnancy. Reproduction 150, 217–225 (2015).

Carambula, S. F. et al. Caspase-3 is a pivotal mediator of apoptosis during regression of the ovarian corpus luteum. Endocrinology 143, 1495–1501 (2002).

Yadav, V. K., Lakshmi, G. & Medhamurthy, R. Prostaglandin F2alpha-mediated activation of apoptotic signaling cascades in the corpus luteum during apoptosis: involvement of caspase-activated DNase. J Biol Chem 280, 10357–10367 (2005).

Juengel, J. L., Garverick, H. A., Johnson, A. L., Youngquist, R. S. & Smith, M. F. Apoptosis during luteal regression in cattle. Endocrinology 132, 249–254 (1993).

Meidan, R., Milvae, R. A., Weiss, S., Levy, N. & Friedman, A. Intraovarian regulation of luteolysis. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 54, 217–228 (1999).

Korzekwa, A. J., Okuda, K., Woclawek-Potocka, I., Murakami, S. & Skarzynski, D. J. Nitric oxide induces apoptosis in bovine luteal cells. J Reprod Dev 52, 353–361 (2006).

Lee, J., Banu, S. K., McCracken, J. A. & Arosh, J. A. Early pregnancy modulates survival and apoptosis pathways in the corpus luteum in sheep. Reproduction 151, 187–202 (2016).

Hata, A. N., Engelman, J. A. & Faber, A. C. The BCL2 Family: Key Mediators of the Apoptotic Response to Targeted Anticancer Therapeutics. Cancer Discov 5, 475–487 (2015).

Barille-Nion, S., Bah, N., Vequaud, E. & Juin, P. Regulation of cancer cell survival by BCL2 family members upon prolonged mitotic arrest: opportunities for anticancer therapy. Anticancer Res 32, 4225–4233 (2012).

Deveraux, Q. L., Takahashi, R., Salvesen, G. S. & Reed, J. C. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature 388, 300–304 (1997).

Srinivasula, S. M. et al. A conserved XIAP-interaction motif in caspase-9 and Smac/DIABLO regulates caspase activity and apoptosis. Nature 410, 112–116 (2001).

Rogakou, E. P., Nieves-Neira, W., Boon, C., Pommier, Y. & Bonner, W. M. Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J Biol Chem 275, 9390–9395 (2000).

Solier, S., Sordet, O., Kohn, K. W. & Pommier, Y. Death receptor-induced activation of the Chk2- and histone H2AX-associated DNA damage response pathways. Mol Cell Biol 29, 68–82 (2009).

Berisha, B., Schams, D., Rodler, D., Sinowatz, F. & Pfaffl, M. W. Expression and localization of members of the thrombospondin family during final follicle maturation and corpus luteum formation and function in the bovine ovary. J Reprod Dev 62(5), 501–510 (2016).

Yamashita, H. et al. Effect of local neutralization of basic fibroblast growth factor or vascular endothelial growth factor by a specific antibody on the development of the corpus luteum in the cow. Mol Reprod Dev 75, 1449–1456 (2008).

Laird, M., Woad, K. J., Hunter, M. G., Mann, G. E. & Robinson, R. S. Fibroblast growth factor 2 induces the precocious development of endothelial cell networks in bovine luteinising follicular cells. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 25, 372–386 (2013).

Woad, K. J. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 2 is a key determinant of vascular sprouting during bovine luteal angiogenesis. Reproduction 143, 35–43 (2012).

Rusnati, M. et al. The calcium-binding type III repeats domain of thrombospondin-2 binds to fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2). Angiogenesis 22, 133–144 (2019).

Farberov, S. & Meidan, R. Fibroblast growth factor-2 and transforming growth factor-beta1 oppositely regulate miR-221 that targets thrombospondin-1 in bovine luteal endothelial cells. Biol Reprod 98, 366–375 (2018).

Raica, M. & Cimpean, A. M. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF)/PDGF Receptors (PDGFR) Axis as Target for Antitumor and Antiangiogenic Therapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 3, 572–599 (2010).

Woad, K. J. et al. FGF2 is crucial for the development of bovine luteal endothelial networks in vitro. Reproduction 138, 581–588 (2009).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3, 1101–1108 (2008).

Kfir, S. et al. Genomic profiling of bovine corpus luteum maturation. PLoS One 13, e0194456 (2018).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Acknowledgements

Supported by a grant from BARD (Binational Agricultural Research & Development Fund - IS-4788-15, RM and MCW) and a grant from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) Project 2018/03798-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B., S.T.M. and R.M. designed the study, conducted and analyzed the in vitro experiments, with the help of K.S. and S.F. The in vivo studies were designed and conducted by J.N.D., R.S. and M.C.W., R.M. and R.B. wrote the manuscript, all other authors reviewed and corrected the manuscript. All authors have approved the submitted version, and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Basavaraja, R., Madusanka, S.T., Drum, J.N. et al. Interferon-Tau Exerts Direct Prosurvival and Antiapoptotic Actions in Luteinized Bovine Granulosa Cells. Sci Rep 9, 14682 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51152-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51152-6

This article is cited by

-

Diverse actions of sirtuin-1 on ovulatory genes and cell death pathways in human granulosa cells

Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (2022)

-

Downregulated luteolytic pathways in the transcriptome of early pregnancy bovine corpus luteum are mimicked by interferon-tau in vitro

BMC Genomics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.