Abstract

We present precipitation isotope data (δ2H and δ18O values) from 19 stations across the tropics collected from 2012 to 2017 under the Coordinated Research Project F31004 sponsored by the International Atomic Energy Agency. Rainfall samples were collected daily and analysed for stable isotopic ratios of oxygen and hydrogen by participating laboratories following a common analytical framework. We also calculated daily mean stratiform rainfall area fractions around each station over an area of 5° x 5° longitude/latitude based on TRMM/GPM satellite data. Isotope time series, along with information on rainfall amount and stratiform/convective proportions provide a valuable tool for rainfall characterisation and to improve the ability of isotope-enabled Global Circulation Models to predict variability and availability of inputs to fresh water resources across the tropics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background & Summary

This database is an outcome of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) coordinated Research Project (CRP) F31004 on ‘Stable isotopes in precipitation and paleoclimatic archives in tropical areas to improve regional hydrological and climatic impact models’. The project was conducted from 2012–2017 with participation from the following member States: Argentina, Australia, Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Japan, Singapore, United States of America (USA) and Vietnam.

The stable isotopes of water (i.e., 18O/16O and 2H/1H, expressed as δ18O and δ2H values hereafter) are effective integrating tracers of regional-scale hydroclimate processes1,2. The key objective of the CRP was to improve understanding of the links between stable isotopes in precipitation and the hydroclimatic factors controlling them in tropical regions from daily to annual timescales and site to regional spatial scales. To achieve this objective the CRP initiative collected daily precipitation samples for analysis of stable isotope ratios of oxygen and hydrogen across the tropics. Several sampling stations with no prior rainfall isotope observations were established. It is noteworthy that this data set is the first systematic effort to capture ground-based daily isotope record of tropical rainfall in all phases (i.e. neutral, warm, and cool) of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Furthermore, the 2015–2016 ENSO event was one of the strongest on record3.

The availability of Global Circulation Models (GCMs) incorporating isotope physics provided a promising framework to study isotopic variability in precipitation4,5,6,7,8. To evaluate the stable isotope fields simulated by such GCMs, the IAEA’s Global Network of Isotopes in Precipitation (GNIP) database9,10 has recurrently been used as the major comprehensive source of data. While isotope-enabled GCMs simulate modern isotopic patterns in global precipitation on monthly and inter-annual time scales reasonably well over mid and high latitude regions, simulations of tropical rainfall need further development6,8. A major reason for this problem is that the physical mechanisms controlling the spatial and temporal isotopic variations in tropical precipitation are still not fully understood. In addition, the poor spatial and temporal coverage of precipitation isotope data in tropical regions poses a challenge to explore the primary drivers of isotope variability. Therefore, an expanded monitoring network in the tropics is required, not only to identify the key controls of isotopic variability, but to improve the reproducibility of GCMs simulations. This improvement may help elucidate the mechanisms (e.g. sub-cloud evaporation, moisture convergence and entrainment) that control isotopic changes in precipitation and enhance the capabilities of climate models to predict variability and availability of fresh water resources. In addition, better understanding of the controls on precipitation isotope variability will lead to improvements in our interpretation of isotope-based proxies in terrestrial and maritime paleoarchives (e.g., caves, corals, lake sediments, and potentially tree-rings)11.

In the tropics, precipitation isotopes mainly correlate negatively with precipitation amounts on a monthly scale. This empirical low-latitude inverse correlation between water isotope ratios and the amount of rainfall, known as the ‘amount effect'12, has been used as a rationale to infer wet and dry paleo-hydroclimate periods based on available maritime and terrestrial paleo proxies across the tropics13. However, the amount effect is not universal over the tropical regions. For example, in SE Asia the effect is relatively strong at two marine island stations (Palau and Bali) but relatively weak at continental coastal stations (e.g., Bangkok and Da Nang)14. Furthermore, the correlation between precipitation amount and isotopic composition is commonly weaker or non-existent on a daily basis compared to monthly time scales2,14,15. This is because the linear regression approach neglects other processes such as moisture convergence and entrainment, resulting in weak correlations across the tropics with >80% of the variance unexplained when using daily data, whereas stronger correlations (30–70% variance explained) are reported when computing monthly means2. These complexities indicate that the isotopic variations in precipitation, even at tropical islands where a pronounced amount-effect is observed, are not directly controlled by rainfall amount but is rather influenced by the other convection related processes (e.g. cloud microphysics, cloud type, moisture transport). This conclusion is supported by several recent studies which have demonstrated that the isotopic variability is associated with regional, rather than local, convective activity (e.g. in North Africa16, Tibet17, Borneo1, Pacific Ocean18,19, India20,21, Australia22, Brazil23 and Costa Rica15). In Costa Rica, isotopic variations also exhibited more complex interactions between variable moisture sources, humidity and orographic lifting15. A gradual decrease in δ18O values of precipitation with cumulative rainfall along upstream air mass trajectories over several days was reported in Tibet17, Northern Australia22, and Southeast Asia24. On the other hand, in some amount-effect-dominated regions, changes in moisture source and air mass trajectories largely influenced sub-monthly or seasonal isotopic variations (e.g. East Africa25,26, Japan27, Namibia28).

It is well known that intra-seasonal isotopic variations are clearly seen in many tropical regions (e.g. Borneo1, Western Pacific19, Northern Australia22). These variations typically manifest as negative excursions in δ18O and δ2H values and typically, but not exclusively, correspond to the wet phases of the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO). Cyclonic lows (i.e., hurricanes, typhoons) may also produce extreme rainfall and negative δ18O and δ2H anomalies. Within the MJO wet phase, large organised convective cloud systems, referred to as mesoscale convective systems (MCSs), account for a large portion of tropical rainfall. Stratiform rainfall associated with MCSs has been shown to be mainly associated with large negative excursions of δ18O and δ2H values in tropical rainfall19,29. Negative isotope anomalies in stratiform rainfall have been linked to deposition of 18O- and 2H-depleted water vapour onto ice particles at altitude which, as they fall, aggregate and melt at mid tropospheric levels29,30. Most recently, the relative influence of bulk precipitation microphysics, cloud type, and surface moisture transport on precipitation amounts and 18O/16O ratios was assessed in the tropics2. This analysis showed that bulk precipitation microphysics and cloud type (i.e., stratiform rain fraction) exert comparable influences on the isotopic composition of precipitation, whereas moisture transport plays an important secondary role in regions of deep atmospheric convection. Reduced Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR) values are indicative of stronger MCS activity and often correlate with low δ18O values in rainfall20,22. Based on these results, we can hypothesise that stratiform rainfall is a major driver of isotopic variability over the amount-effect dominated region. However, currently both spatial and temporal coverage of precipitation isotope data is insufficient to adequately test the hypothesis.

Here we present stable isotope data for daily precipitation collected at nineteen stations at both maritime and continental locations within the tropics; ten stations are (near-) coastal and nine are located from ≈ 80 to 600 km inland. We also calculated daily mean stratiform rainfall area fractions at these stations using TRMM and Global Precipitation Mapping (GPM) satellite observations.

Methods

Sampling and analysis

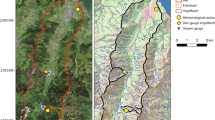

Details of the sampling stations including location, updated Köppen-Geiger climate zone classification31, mean annual precipitation and temperature, sampling period and number of samples collected are provided in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Rainfall samples were usually collected at 9am local time but variations of up to a few hours occurred on some occasions for practical reasons.

Map of the 19 sampling stations (green dots) and 229 GNIP (Global Network of Isotopes in Precipitation) tropical stations (pink dots; ranging from 23.76°N/23.83°S and 90.30°W/125.26°E). Geographical coordinates for stations of this study are provided in Table 1.

Table 2 provides sampling, laboratory and instrumental details along with the analytical precision claimed by the individual laboratories. Most stations used the IAEA-designed rain collector32 (Palmex, Zagreb, Croatia) which minimises secondary evaporation from the sample.

All isotope data are reported as δ2H and δ18O values (in ‰) relative to the VSMOW/SLAP scale with δVSMOW defined as the zero point: δ = ((Rsample-RVSMOW)-1)*1000 (‰), where R corresponds to the absolute isotope abundance ratios of 2H/1H and 18O/16O.

Calculation of Stratiform Rainfall Fraction

The daily mean stratiform rainfall area fraction (Fst) was calculated to examine the influence of stratiform rainfall on the daily isotopic variability. Fst is defined as the average percent of rainfall area covered by stratiform rainfall over the 5° x 5° longitude/latitude box centered over each isotope monitoring station. We used the Ku-band Precipitation Radar (KuPR) convective/stratiform classification data from version 5, level 2 product of GPM (Global Precipitation Measurement) Core Observatory (https://pmm.nasa.gov/GPM), which is a successor of the TRMM Precipitation Radar. The GPM satellite flies at an altitude of 407 km in a non-sun-synchronous orbit and completes roughly 16 orbits per day between 65° N and 65° S. The KuPR’s horizontal footprint size along a track (swath width) is 245 km. Based on this swath width, 164 orbits are required to cover the whole equator (roughly 40,000 km) corresponding to around 10 days. This means that only a few GPM orbits pass through the domain (5° x 5° longitude/latitude box) within 10 days and so we cannot obtain daily convective/stratiform classification data from the satellite. As an alternative approach, we used area averaged (5° x 5° box) daily precipitation to estimate the daily Fst. In the tropics, stratiform rainfall area is significantly larger than the convective rainfall area, and the increase in rain area is more likely to result in larger total rain amounts33,34. We found statistically significant relationships of area-averaged rainfall amount (Parea) to Fst over the study domains at fourteen stations (i.e., Cairns, Darwin, 28 Millas, Heredia, Barisal, Cox´s Bazar, Port Blair, Nanyang Tech., Mulu, Ho Chi Minh City (HCM City), Kuala Terengganu., Kuching, Abetifi, and Amedzofe) from 2014 to 2017 (p < 0.05, R2 range = 0.25–0.72, mean R2 = 0.53). As shown in Fig. 2, combining data from the 14 stations show a strong correlation between Parea and Fst (R2 = 0.87, p < 0.01). However, at five inland or slightly extra-tropical stations (i.e., Rio Claro, Addis Ababa, Windhoek, Nagoya and SP Reyes) the relationships were weak, and we excluded these stations from further analysis. We then applied the correlation shown in Fig. 2 to a satellite-based daily precipitation dataset to estimate the daily Fst over the study domain at 14 stations. A Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) Multi-satellite Precipitation Analysis product, namely TMPA 3B42, was used to estimate area-averaged daily precipitation at each station. The TMPA 3B42 product has a 3-hourly temporal resolution and a 0.25° spatial resolution35. Original data are available online at http://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datacollection/TRMM_3B42_V7.shtml.

Relationship between stratiform rainfall area fraction (Fst) and the area-averaged rainfall amount (Parea) over the 5° × 5° longitude/latitude box centred on each station during the period where rainfall was sampled for isotopic analysis. Orange dots represent each individual data. Blue circles with error bars represent the average and standard deviation in precipitation intensity bins for each 0.05 mm/h interval up to 1.5 mm/h. Solid curved line shows a logarithmic regression of averaged values.

Figure 3 shows the correlation between the 10-day moving average rainfall isotope data and stratiform rainfall area fractions >0.01 for 14 tropical stations. Since there is a time lag for organized convective cloud systems (MCSs) in the upwind region to arrive at rainfall sampling stations, the moving average improves correlation compared to using the daily data at most stations. The stations Heredia and 28 Millas in Costa Rica, Darwin and Cairns in Australia, Amedzofe in Ghana, Nanyang Tech in Singapore, Mulu in Malaysia and HCM City in Vietnam had the strongest correlations (R2 = 0.28–0.58) while the remaining stations had weaker or insignificant correlations (p > 0.05) (Table 3). Figure 4 shows a time series for the 10-day moving averages of rainfall isotope data and stratiform rainfall area fraction at Cairns, where a relatively strong anti-phase variation of these two parameters (R2 = 0.43) is observed.

Technical Validation

All laboratory analyses were carried out using infrared laser-absorption spectrometry either by Off-Axis Integrated Cavity Output Spectroscopy (Los Gatos Research, San Jose, CA, USA) or by Cavity Ring Down Spectroscopy (Picarro, Santa Clara, CA, USA). These spectrometers can produce accurate and precise results provided that volatile organic compounds do not cause spectral interferences. However, such interferences are generally absent from rainfall samples and can easily be monitored using instrument software.

The datasets presented here were quality controlled by the individual investigators and laboratories. During the CRP participants were provided with guidance on the production, use and calibration of in-house (secondary) standard waters traceable to the International Measurement Standards VSMOW and SLAP (IAEA 2019) to ensure analytical accuracy and optimise quality control procedures. Most of the CRP’s laboratories participated in the IAEA Water Isotope Inter-Comparison WICO201636 as well as an unofficial CRP-wide inter-comparison.

Data Records

Data sets are available at figshare.com (https://figshare.com/s/fdfabb43a844cad530a5). The file ‘CRP isotopes’ contains stable isotope data in daily rainfall at 19 stations sampled within the period 2012 to 2017. They are recorded in the following order: Local sampling start date/time (YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM), local sampling end date/time (YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM), precipitation δ18O (‰ VSMOW), precipitation δ2H (‰ VSMOW), precipitation d-excess (‰ VSMOW), precipitation amount (mm). Note that at some stations only the sampling end date was recorded (sampling of 24-hr rainfall occurred at 9:00 local time). Empty cells indicate that no data was obtained.

The file ‘CRP stratiform P’ contains calculated stratiform precipitation area fraction for the subset of 14 stations for which this fraction could be calculated (five stations were excluded, see above). They are recorded in the following order: Local sampling start date/time (YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM), local sampling end date/time (YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM), sampled precipitation amount (mm), precipitation δ2H (‰ VSMOW), precipitation δ18O (‰ VSMOW), precipitation d-excess (‰ VSMOW), satellite observation date (YYYY-MM-DDT), daily mean area-averaged precipitation amount (mm), daily mean stratiform precipitation area-fraction, moving 10-day average precipitation δ18O (‰ VSMOW), moving 10-day average stratiform precipitation area-fraction. Stratiform rainfall area fractions <0.01 were disregarded due to their high uncertainty. Empty cells indicate that no data was obtained.

Usage Notes

We encourage interested parties to contact the site investigators to explore possible collaboration opportunities based on these data. It is noted that some data have been published in peer-reviewed journals.

References

Moerman, J. W. et al. Diurnal to inter annual rainfall δ18O variations in northern Borneo driven by regional hydrology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 369–370, 108–119 (2013).

Konecky, B. L., Noone, D. C. & Cobb, K. M. The influence of competing hydroclimate processes on stable isotope ratios in tropical rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 1622–1633 (2019).

Santoso, A., Mcphaden, M. J. & Cai, W. The defining characteristics of ENSO extremes and the strong 2015/2016 El Niño. Rev. Geophys. 55(4), 1079–1129 (2017).

Joussaume, S., Sadourny, R. & Jouzel, J. A general circulation model of water isotope cycles in the atmosphere. Nature 311, 24–29 (1984).

Hoffmann, G. & Heimann, M. Water isotope modelling in the Asian monsoon region. Quat. Int. 37, 115–128 (1997).

Risi, C., Bony, S., Vimeux, F. & Jouzel, J. Water-stable isotopes in the LMDZ4 general circulation model: model evaluation for present-day and past climates and applications to climatic interpretations of tropical isotopic records. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 115, 1–27 (2010).

Risi, C. et al. Process-evaluation of tropospheric humidity simulated by general circulation models using water vapor isotopologues: 1. Comparison between models and observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 117, 1–26 (2012).

Putman A. L., Fiorella, R. P., Bowen, G. J., Cai, Z. A global perspective on local meteoric water lines: Meta‐analytic insight into fundamental controls and practical constraints. Water Resour. Res., 55, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR025181 (2019).

International Atomic Energy Agency. Global Network of Isotopes in Precipitation (GNIP). https://www.iaea.org/services/networks/gnip (accessed 2019-04-14)

Terzer, S., Wassenaar, L. I., Araguás-Araguás, L. J. & Aggarwal, P. K. Global isoscapes for δ18O and δ2H in precipitation: improved prediction using regionalized climatic regression models. Hydrol. Earth Sys. Sci. 17, 4713–4728 (2013).

Nott, J. Palaeotempestology: the study of prehistoric tropical cyclones - a review and implications for hazard assessment. Env. Int. 30, 433–447 (2004).

Dansgaard, W. Stable isotopes in precipitation. Tellus 16, 436–468 (1964).

Tharammal, T., Bala, G. & Noone, D. Impact of deep convection on the isotopic amount effect in tropical precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 1505–1523 (2017).

Kurita, N., Ichiyanagi, K., Matsumoto, J., Yamanaka, M. D. & Ohata, T. The relationship between the isotopic content of precipitation and the precipitation amount in tropical regions. J. Geochem. Explor. 102, 113–122 (2009).

Sanchez-Murillo, R. et al. Key drivers controlling daily stable isotope variations in precipitation of Costa Rica: Caribbean Sea versus eastern Pacific Ocean moisture sources. Quat. Sci. Rev. 131(B), 250–261 (2016).

Risi, C. et al. What controls the isotopic composition of the African monsoon precipitation? Insights from event-based precipitation collected during the 2006 AMMA field campaign. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L24808 (2008).

Gao, J., Masson-Delmotte, V., Risi, C., He, Y. & Yao, T. What controls precipitation δ18O in the southern Tibetan Plateau at seasonal and intra-seasonal scales? A case study at Lhasa and Nyalam. Tellus 65, 21043 (2013).

Conroy, J. L., Cobb, K. M. & Noone, D. Comparison of precipitation isotope variability across the tropical Pacific in observations and SWING2 model simulations. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 5867–5892 (2013).

Kurita, N. Water isotopic variability in response to mesoscale convective system over the tropical ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 1–15 (2013).

Lekshmy, P. R., Midhun, M., Ramesh, R. & Jani, A. R. 18O depletion in monsoon rain relates to large scale organized convection rather than the amount of rainfall. Sci. Rep. 4(5661), 1–5 (2014).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Atmospheric controls on the precipitation isotopes over the Andaman Islands, Bay of Bengal. Sci. Rep. 6, 19555 (2016).

Zwart, C., Munksgaard, N. C., Kurita, N. & Bird, M. I. Stable isotopic signature of Australian monsoon controlled by regional convection. Quat. Sci. Rev. 151, 228–235 (2016).

Gastmans, D. et al. Controls over spatial and seasonal variations on isotopic composition of the precipitation along the central and eastern portion of Brazil. Iso. Environ. Health Studies 53(5), 518–538 (2017).

Cai, Z., Tian, L. & Bowen, G. J. ENSO variability reflected in precipitation oxygen isotopes across the Asian Summer Monsoon region. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 475, 25–33 (2017).

Levin, N. E., Zipser, E. & Cerling, T. Isotopic composition of waters from Ethiopia and Kenya: Insights into moisture sources for eastern Africa. J. Geophys. Res. 114, D23306 (2009).

Soderberg, K. et al. Using atmospheric trajectories to model the isotopic composition of rainfall in central Kenya. Ecosphere 4(3), 1–18 (2013).

Kurita, N., Fujiyoshi, F., Nakayama, T., Matsumi, Y. & Kitagawa, H. East Asian Monsoon controls on the inter-annual variability in precipitation isotope ratio in Japan. Clim. Past. 11, 339–353 (2015).

Kaseke, K. F. et al. Precipitation Origins and Key Drivers of Precipitation Isotope (18O, 2H, and 17O) Compositions Over Windhoek. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 123, 7311–7330 (2018).

Aggarwal, P. K. et al. Proportions of convective and stratiform precipitation revealed in water isotope ratios. Nature Geosci. 9, 624–629 (2016).

Lekshmy, P. R., Midhun, M. & Ramesh, R. Influence of stratiform clouds on δD and δ18O of monsoon water vapour and rain at two tropical coastal stations. J. Hydrology 563, (354–362 (2018).

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Sys. Sci. Disc. 4(2), 439–473 (2007).

Gröning, M. H. et al. A simple rain collector preventing water re-evaporation dedicated for δ18O and δ2H analysis of cumulative precipitation samples. J. Hydrol. 448, 195–200 (2012).

Schumacher, C. & Houze, R. A. J. Stratiform rain in the tropics as seen by the TRMM precipitation radar. J. Climate 16, 1739–1756 (2003).

Rapp, A. D., Peterson, A. G., Frauenfeld, O. W., Quiring, S. M. & Roark, E. B. Climatology of Storm Characteristics in Costa Rica using the TRMM Precipitation Radar. J. Hydrometeor. 15, 2615–2633 (2014).

Huffman, G. J., Bolvin, D. T. TRMM and other data precipitation data set documentation. NASA, Greenbelt, USA, 28 (2.3), p.1 (2013).

Wassenaar, L. I. et al. Seeking excellence: An evaluation of 235 international laboratories conducting water isotope analyses by isotope‐ratio and laser‐absorption spectrometry. Rapid Comm. Mass Spect. 32, 393–406 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial and logistical support from the IAEA Isotope Hydrology Section (Dr. P.K. Aggarwal, Dr. S. Terzer and Dr. L.I. Wassenaar). MB and CZ received support from the Australian Research Council (FL140100044 and an Australian Postgraduate Award). LW acknowledges support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (IIA-1427642 and EAR-1554894). DG acknowledges support from the Brazilian FAPESP Sao Paulo Research Foundation (project 2015/15749-2). RS-M acknowledges support from Universidad Nacional (Heredia, Costa Rica) through grants SIA-0482-13, SIA-0378-14, and SIA-0101-14 and IAEA Technical Cooperation Project (COS7005: Ensuring water security and sustainability of Costa Rica).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.C.M., N.K., R.S.-M., N.A., L.A., D.L.B., M.I.B., S.C., N.K.C., K.M.C., S.A.E., G.E.-H., S.Y.G., J.G., D.G., K.F.K., S.K., M.R.M., M.M., S.C.P., V.d.S., H.S., L.W., H.Y. and C.Z. contributed to data collection, methodology and commented on the manuscript. N.C.M., N.K. and R.S.-M. drafted the manuscript and main figures. N.K. extracted TRMM/GPM satellite data and calculated stratiform rainfall fractions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

N.C.M., N.K., R.S.-M., N.A., L.A., D.L.B., M.I.B., S.C., N.K.C., K.M.C., S.A.E., G.E.-H., S.Y.G., J.G., D.G., K.F.K., S.K., M.R.M., M.M., S.C.P., V.d.S., H.S., L.W., H.Y. and C.Z. declare no competing interest, financial and non-financial.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Munksgaard, N.C., Kurita, N., Sánchez-Murillo, R. et al. Data Descriptor: Daily observations of stable isotope ratios of rainfall in the tropics. Sci Rep 9, 14419 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50973-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50973-9

This article is cited by

-

imc-precip-iso: open monthly stable isotope data of precipitation over the Indonesian Maritime Continent

Journal of Data, Information and Management (2024)

-

Shift in groundwater recharge of the Bengal Basin from rainfall to surface water

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Isotopic variability in tropical cyclone precipitation is controlled by Rayleigh distillation and cloud microphysics

Communications Earth & Environment (2022)

-

Distinguishing the Regional Atmospheric Controls on Precipitation Isotopic Variability in the Central-Southeast Portion of Brazil

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2022)

-

Hydroclimatic vulnerability of peat carbon in the central Congo Basin

Nature (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.