Abstract

There is a wide variation of flowering time among lines of Brassica rapa L. Most B. rapa leafy (Chinese cabbage etc.) or root (turnip) vegetables require prolonged cold exposure for flowering, known as vernalization. Premature bolting caused by low temperature leads to a reduction in the yield/quality of these B. rapa vegetables. Therefore, high bolting resistance is an important breeding trait, and understanding the molecular mechanism of vernalization is necessary to achieve this goal. In this study, we demonstrated that BrFRIb functions as an activator of BrFLC in B. rapa. We showed a positive correlation between the steady state expression levels of the sum of the BrFLC paralogs and the days to flowering after four weeks of cold treatment, suggesting that this is an indicator of the vernalization requirement. We indicate that BrFLCs are repressed by the accumulation of H3K27me3 and that the spreading of H3K27me3 promotes stable FLC repression. However, there was no clear relationship between the level of H3K27me3 in the BrFLC and the vernalization requirement. We also showed that if there was a high vernalization requirement, the rate of repression of BrFLC1 expression following prolonged cold treatments was lower.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flowering is an event that transitions a plant from vegetative to reproductive growth, and is regulated by both internal and external factors1,2. Because plants use the energy accumulated during the vegetative growth period for the reproductive growth phase to propagate offspring, flowering is a crucial developmental process in a plant’s life cycle1,2. Flowering time is also important for the yield of crops or vegetables, and the regulation of flowering time is an important goal of plant breeding2,3. Changes to flowering time can broaden the area or the period of suitable cultivation, and lead to tolerance against changing climatic conditions1,2.

Many plant species require prolonged cold exposure, generally encountered during the course of winter, before flowering and setting seed. Without exposure to a prolonged cold period, flowering is blocked. This process is known as vernalization, which is derived from the Latin word vernalis, meaning ‘of, relating to, or occurring in the spring’4. Variation in the requirement for vernalization exists in plant species1,5,6. A vernalization requirement is an evolutionary adaptation to temperate climates, preventing flowering before encountering a winter season and ensuring flowering occurs under the more favorable weather conditions of spring1,2,6. Vernalization requirement is also important for the quantity and quality of crop production1,2,6. In vegetative crops, early bolting and flowering caused by a low vernalization requirement can limit the potential for increase in yield or devalue the products2,3.

The molecular mechanism of vernalization has been studied extensively in Arabidopsis thaliana, and an abundance of information about its mechanism has been discovered. In A. thaliana, the two genes, FRIGIDA (FRI)7 and FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC)8,9,10, are the major determinants of flowering time1,5. FRI is one of the causative genes of natural variation of vernalization in A. thaliana, and FRI acts as a positive regulator of FLC7. Another flowering regulator, FLC, encodes a MADS-box transcription factor and acts as a floral repressor8,9,10. FLC is expressed before cold exposure and its expression is repressed by vernalization11. Cold exposure induces the formation of a plant homeodomain-polycomb repressive complex 2 (PHD-PRC2) that results in an increased abundance of tri-methylation of the 27th lysine of histone H3 (H3K27me3) at the nucleation region of the FLC locus12,13. Upon return to warm conditions, H3K27me3 spreads over the entire FLC gene and silencing of FLC is maintained14,15.

Varieties of Brassica rapa L. include Chinese cabbage (var. pekinensis), pak choi (var. chinensis), komatsuna (var. perviridis), turnip (var. rapa), and oilseed (var. oleifera). B. rapa is closely related to A. thaliana, both being members of the Brassicaceae family. Bolting caused by low temperature leads to a reduction in the yield and quality of the harvested products of leafy vegetables such as Chinese cabbage, pak choi, and komatsuna or root vegetables such as turnip. Therefore, a line highly resistant to bolting (i.e., possessing a high vernalization requirement) is desirable for the breeding of B. rapa cultivars2,3. Comparative genetic and physical mapping and genome sequencing studies have revealed that the B. rapa genome has undergone a whole-genome triplication, which results in multiple copies of paralogous genes16,17,18. Flowering time genes have been characterized and there are two FRI paralogs in B. rapa19,20. B. rapa has four FLC paralogs (BrFLC1, BrFLC2, BrFLC3, BrFLC5)19,20,21, of which BrFLC5 is a pseudogene in the reference genome due to the deletion of two exons16,21. BrFLC genes are expressed before vernalization and their expression is repressed following vernalization2,3,22. The silencing of the three functional BrFLC paralogs is associated with increased H3K27me3 around the transcription start site22. FLC paralogs co-localized with quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for flowering time in B. rapa23,24,25,26,27. Thus, FLC genes are considered to be key regulators of the vernalization requirement in B. rapa2,3.

In B. rapa, FRI gene function has not yet been confirmed, and how the multiple FLC genes are involved in the vernalization requirements is not fully understood. In this study, we characterized two BrFRI genes, BrFRIa and BrFRIb, and confirmed BrFRIb functions as an activator of FLC. The relationship between expression levels of BrFRIs (BrFRIa + BrFRIb) or BrFLCs (BrFLC1 + BrFLC2 + BrFLC3 + BrFLC5) and days to flowering was examined. We also examined the expression levels of BrFLC genes and the accumulation of H3K27me3, before and after prolonged cold treatment, in two lines that vary in their vernalization requirements. Our results suggest that the steady state of the sum of functional BrFLC expression levels and the level of reduction of this expression by vernalization are key factors in determining the vernalization requirement in B. rapa.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Nine B. rapa lines (RJKB-T02, RJKB-T17, ‘Harunosaiten’, ‘Harusakari’, ‘Natsumaki 50nichi’, ‘Yellow sarson’, BRA2209, Homei, and Osome) were used as plant materials to examine days to flowering after four weeks of cold treatment (Supplementary Table 1). In total, 37 B. rapa lines including the above nine lines were used for sequence determination of BrFRI genes. Genetic distances among 33 of the 37 lines have been examined28 and these 33 lines all need vernalization for flowering (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Seeds were surface sterilized and grown on agar solidified Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates with 1% (w/v) sucrose under long day (LD) conditions (16 h light) at 22 °C. For vernalizing cold treatments, 14-day seedlings on MS plates were treated for 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 8 weeks at 4 °C under LD conditions (16 h light) or four weeks at 4 °C and then seven days in normal growth condition.

To examine the flowering time in the nine lines, seeds were surface sterilized and grown on MS plates with 1% (w/v) sucrose under LD conditions (16 h light) at 22 °C for 14 days, and 14-day seedlings on MS plates were treated for four weeks at 4 °C under LD conditions (16 h light). After cold treatment, the plants were transferred to soil and grown in normal growth conditions. The number of days until the appearance of flower buds was counted and scores were set based on the criteria shown in Supplementary Table 2. More than ten plants of each line were used for examining the flowering time.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR/qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from 1st and 2nd leaves using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega). The cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng total RNA using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (Toyobo). For RT-PCR, the cDNA was amplified using Quick Taq® HS DyeMix (Toyobo). PCR was performed using the following conditions; 1 cycle of 94 °C for 2 min, 25, 30, or 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 30 s. Primer sequences used for RT-PCR are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

RT-qPCR was performed using LightCycler 96 (Roche). cDNA was amplified using FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche). PCR conditions were 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 15 s, and Melting program (60 °C to 95 °C at 0.1 °C/s). After amplification cycles, each reaction was subjected to melt temperature analysis to confirm single amplified products. The expression level of each gene relative to BrACTIN29 was automatically calculated using automatic CQ calling according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche). Data presented are the average and standard error (s.e.) calculated from three biological and experimental replications. Primer sequences used for RT-qPCR are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Sequencing DNA fragments of BrFRI and BrFLC genes

The region covering BrFRIa or BrFRIb was amplified using primers, FRIa-F1/-R1 or FRIb-F1/-R1, respectively, using genomic DNA as templates. DNAs from 37 B. rapa lines were used for the direct sequencing of PCR products (Supplementary Table 1). PCR products were treated by illustra ExoProStar (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and were sequenced using ABI Prism 3130 (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences used for direct sequencing are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Regions covering the coding sequence of each BrFLC paralog in RJKB-T02, RJKB-T17, RJKB-T24, Homei, ‘Harunosaiten’, and BRA2209, were amplified using cDNA as templates (Supplementary Table 1). PCR products were treated by illustra ExoProStar (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and were sequenced using ABI Prism 3130 (Applied Biosystems). PCR was performed using the following conditions; 1 cycle of 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 30 s. Primer sequences used for direct sequencing are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

The genomic regions covering BrFLC1, BrFLC2, and BrFLC3 and their promoter regions were amplified using genomic DNA as a template in BRA2209. PCR products were then cloned into pGEM®-T Easy vector (Promega). Nucleotide sequences of three clones of PCR products were determined with the ABI Prism 3130 (Applied Biosystems), and the data were analyzed using Sequencher (Gene Codes Corporation, MI, USA). PCR was performed using the following conditions; 1 cycle of 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 2 min. Primer sequences and their positions used for PCR and sequencing are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3.

Constructs and plant transformation

Using cDNAs from leaves of RJKB-T24, either BrFRIb or BrFLC1, 2, or 3 cDNA fragments were amplified by RT-PCR using primers designed to add Bam HI and Sac I restriction sites to the 5′- and 3′-ends (Supplementary Table 3), and PCR products were then cloned into pGEM®-T Easy vector (Promega). DNA fragments of BrFRIb or BrFLC1, 2, or 3 cDNA was inserted into Bam HI and Sac I restriction sites of pBI121. These constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105, and transformation of Columbia-0 (Col) accession in A. thaliana was carried out by the floral dip procedure30. Transgenic seedlings were selected through resistance to kanamycin on a selection medium.

Seeds of T2 plants were sown on MS medium with or without four weeks of cold treatment and grown under LD conditions (16 h light) at 22 °C. After growing plants on MS medium, they were transferred to soil and grown under the conditions described above. Flowering time in A. thaliana was expressed as the number of rosette leaves at the time of flowering.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP experiments were performed as described by Buzas et al.31. One gram of non-crosslinked chromatin taken from the 1st and 2nd leaves of Homei and ‘Harunosaiten’ was used (Supplementary Table 1). Mononucleosomes were obtained by MNase digestion and samples were sonicated twice. The samples were incubated with anti-H3K27me3 (Millipore, 07-449) antibodies for 4 h and then with protein A agarose for 2 h at 4 °C with rotation. The protein A agarose was washed, and immunoprecipitated DNAs were eluted by proteinase K treatment followed by a clean-up using Qiagen PCR cleanup kit (Qiagen). We validated the enrichment of purified immunoprecipitated DNAs by ChIP-qPCR using the previously developed positive and negative control primer sets of H3K27me3 (Supplementary Table 3)22. Three independent ChIP experiments were carried out on each sample for biological replicates.

ChIP-qPCR was performed by the same method as the RT-qPCR using the immunoprecipitated DNA as a template. The H3K27me3 level of each BrFLC gene relative to the SHOOT MERISTEMLESS gene (BrSTM)22, which has H3K27me3 accumulation, was automatically calculated using automatic CQ calling according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche). The difference in the amplification efficiency between primer pairs was corrected by calculating the difference observed by qPCR amplifying the input-DNA as a template. Data presented are the average and standard error (s.e.) from three biological and experimental replications. Primer sequences used for ChIP-qPCR are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Amino acid sequence analysis

Using the genome sequences of BrFRIa and BrFRIb in 37 B. rapa lines, predicted amino acid sequences were obtained. The amino acid sequences of BrFRIa and BrFRIb in 37 lines of B. rapa, two BoFRI32, and AtFRI (AF228499.1) were aligned using ClustalW (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/search/clustalw-j.html). A phylogenetic tree was constructed with the neighbor joining method33, and the bootstrap probabilities of 1,000 trials were calculated.

Results

Variation of the days to flower after prolonged cold treatment

To determine the duration of prolonged cold treatment, we determined the days to flowering after prolonged cold treatment. We examined the percentage of plants that had flowered in two early (Homei and RJKB-T02) and two late flowering lines (RJKB-T17 and BRA2209) with different durations of cold treatments, i.e., two, three, four, or five weeks. After two weeks of cold treatment, no line flowered within 100 days (Supplementary Fig. 3). All plants of two early flowering lines flowered after three weeks of cold treatment, while no plant of two late flowering lines flowered (Supplementary Fig. 3). In two late flowering lines, four of six plants of RJKB-T17 flowered following four weeks of cold treatment, while no plant in BRA2209 flowered following four weeks of cold treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3). Following five weeks of cold treatment, all lines flowered even though there were differences in days to flowering (Supplementary Fig. 3). From these data, we determined that four weeks of cold treatment is suitable for detecting differences in vernalization requirement among the B. rapa lines.

Next, we examined the days to flower after four weeks of cold treatment in nine B. rapa lines. Scores were used for the evaluation of flowering time, because some plants in the late flowering line did not flower within 100 days (see Methods). ‘Yellow Sarson’ and Homei were early flowering, while Osome, BRA2209, RJKB-T17, and ‘Harunosaiten’ were late flowering (Fig. 1).

Functional analysis of FRIGIDA in B. rapa

As the early flowering phenotype in some A. thaliana accessions is due to the loss of function of AtFRI, we examined the sequence variation in BrFRI genes using 37 lines of B. rapa including the nine lines whose flowering time had been assessed (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). In the reference genome, Chiifu-401-42, there are two FRI genes, BrFRIa (Bra029192, A03) and BrFRIb (Bra035723, A10). The BrFRIa sequence in the reference genome is comprised of three exons and showed sequence similarity to AtFRI and BoFRIa. BoFRIa32 and AtFRI7 have already been shown to be functional activators of FLC, considering that BrFRIa in Chiifu-401-42 is functional; sharing a high sequence similarity to BoFRIa suggests that BrFRIa may perform a similar function. The nucleotide sequence of BrFRIa in 37 lines was determined by direct sequencing. There was a high sequence similarity of the amino acid sequence of BrFRIa among 37 B. rapa lines (from 97.8% to 100.0%) (Supplementary Table 4). The amino acid sequence identities between BrFRIa and AtFRI were from 56.8% to 57.5% and from 87.9% to 88.1% between BrFRIa and BoFRIa (Supplementary Figs 4, 5, Supplementary Table 4). Lines showing different flowering times had identical amino acid sequences of BrFRIa (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 4), indicating that the differences of vernalization requirements among the nine B. rapa lines are not due to amino acid sequence variation in BrFRIa.

In contrast, the annotated BrFRIb (Bra035723), termed BrFRIbΔ, is comprised of two exons, and appears to lack the 3rd exon (Supplementary Fig. 6). We mapped RNA-seq reads that was previously performed34 using 14-day leaves in RJKB-T23 and RJKB-T24 on the region covering BrFRIbΔ and found another ORF, which contains three exons (Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that an unannotated functional copy of BrFRIb is present in the reference genome sequence. As further evidence of this, transformation of the annotated BrFRIbΔ driven with the 35S CaMV promoter into the Col accession of A. thaliana, which lacks AtFRI function, did not complement the AtFRI function (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating that the annotated BrFRIbΔ is non-functional.

We examined whether the newly identified BrFRIb in this study is functional. We transformed BrFRIb into the Col accession of A. thaliana, and 14 independent T1 plants were obtained. The flowering time segregated in T2 plants that were derived from three independent T1 plants, and the flowering times of T2 plants with the transgene were later than the T2 plants without the transgene or wild type Col (Student t-test, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2A). We also found that T2 plants from some T1 lines did not flower even when the rosette leaf number was greater than 45. We confirmed the induction of AtFLC expression in these late flowering transgenic plants (Fig. 2B). T2 seeds were treated with cold for four weeks, and then examined for flowering time. The flowering time in T2 plants with the transgene was the same as without the transgene (Fig. 2A). Repression of AtFLC by cold treatment was observed in T2 plants with the transgene (Fig. 2B,C), indicating that AtFLC induced by BrFRIb is suppressed by cold treatment. These results indicate that BrFRIb functioned like AtFRI.

Overexpression of BrFRIb causes late flowering and induce AtFLC expression. (A) Number of rosette leaves and flowering-time phenotypes in T2 plants with overexpressing BrFRIb with (V) or without vernalization (NV). +TG and −TG show the presence and absence of transgenes (TG), respectively. **p < 0.01 (Students t-test) (B) RT-PCR analysis showing transcription of BrFRIb and AtFLC before and after four weeks of cold treatment. Non-vernalized Col line is included as a control. AtGAPD was used as a control to demonstrate equal RNA loading. NV, non-vernalized; V, vernalized. (C) RT-qPCR analysis of AtFLC with (V) and without (NV) four weeks of cold treatment. AtFLC expression level relative to AtGAPD is shown in the y-axis. Non-vernalized Col line is included as a control. Data presented are the average and standard error (s.e.) from three biological and experimental replications. **p < 0.01 (Students t-test).

We determined the nucleotide sequence of BrFRIb in 37 lines by direct sequencing. There was a high sequence similarity of the amino acid sequence of BrFRIb among B. rapa lines (from 95.8% to 100.0%) (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 4). The amino acid sequence identity between BrFRIb and AtFRI were from 59.4% to 59.9% and from 85.8% to 87.4% between BrFRIb and BoFRIb (Supplementary Figs 4, 5, Supplementary Table 4). The amino acid sequence identities ranged from 63.1% to 64.3% between BrFRIa and BrFRIb (Supplementary Table 4). Like BrFRIa, lines showing different flowering time had identical amino acid sequences of BrFRIb (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 4), indicating that the difference of vernalization requirement among nine B. rapa lines is not due to the amino acid sequence variation of BrFRIb.

Next, we examined whether transcription levels of BrFRI genes contribute to the difference of vernalization requirement. We examined the transcription levels of BrFRIa, BrFRIb, or BrFRIs (BrFRIa + BrFRIb) by RT-qPCR in 14-day leaves of the nine lines whose flowering time had been measured (Figs 1 and 3A–C). Expression in ‘Yellow sarson’ was the lowest, while RJKB-T17 and BRA2209 had the highest expression levels of BrFRIs, with expression levels in BRA2209 being 6.8 times higher than that in ‘Yellow sarson’ (Fig. 3C). There was a moderate correlation between BrFRIs expression level and flowering time but it was not statistically significant (r = 0.56, p > 0.05) (Fig. 3D). There was no correlation between BrFRIa or BrFRIb expression level and flowering time (Supplementary Fig. 9).

The relationship between the expression levels of BrFRI and flowering time. (A–C) There is variation of the expression levels of BrFRIa, BrFRIb, or BrFRIs (BrFRIa + BrFRIb) among nine B. rapa lines. Expression level of each gene relative to BrACTIN (BrACT) is calculated, and the y-axis shows the ratio against RJKB-T02. Data presented are the average and standard error (s.e.) from three biological and experimental replications. Letters above the bars indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 (Tukey-Kramer test). (D) The relationship between the expression levels of BrFRIs and flowering time score in nine B. rapa lines.

Three FLOWERING LOCUS C paralogs function as floral repressors in B. rapa

We examined whether BrFLC is a key regulator of the differences in vernalization requirements for B. rapa. First, we confirmed all three BrFLCs (BrFLC1, BrFLC2, and BrFLC3) function as floral repressors. Transformation of a 35 S promoter::BrFLC1cDNA, 35 S promoter::BrFLC2cDNA, or 35 S promoter::BrFLC3cDNA construct into the Col accession of A. thaliana, where AtFLC was not expressed because of loss of function of AtFRI, revealed that transgenic plants with overexpressed BrFLC1, BrFLC2, or BrFLC3 showed late flowering (Supplementary Fig. 10), confirming that all three BrFLCs function as floral repressors like AtFLC.

Second, we examined the amino acid sequences of three functional BrFLC paralogs (BrFLC1, BrFLC2, and BrFLC3) in RJKB-T24, which was the line used for testing the 35 S promoter::BrFLC constructs. The amino acid sequence of the early flowering lines, RJKB-T02 and Homei, and the late flowering lines, RJKB-T17, ‘Harunosaiten’, and BRA2209, were also examined. A comparison of the amino acid sequences for each BrFLC paralog showed no sequence differences between lines, indicating that any difference in flowering time is not due to amino acid sequence variation.

Third, we examined the expression levels of BrFLC genes in the nine B. rapa lines whose flowering time had been measured (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1) using a primer set that can amplify all four FLC genes. The lowest level of BrFLCs was in early flowering RJKB-T02 and the highest in late flowering RJKB-T17; the expression level in RJKB-T17 was 3.6 times higher than in RJKB-T02 (Fig. 4A). The expression levels of BrFRIs and BrFLCs showed a weak correlation (r = 0.23, p > 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 11). There was a high correlation between BrFLCs expression level and flowering time (r = 0.73, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the expression level of BrFLCs before cold treatment is associated with the vernalization requirement.

The relationship between the expression level of BrFLCs and flowering time. (A) There is variation of the expression levels of BrFLCs (BrFLC1 + BrFLC2 + BrFLC3 + BrFLC5) among nine B. rapa lines. Expression level of each gene relative to BrACTIN (BrACT) is calculated, and the y-axis shows the ratio against RJKB-T02. Data presented are the average and standard error (s.e.) from three biological and experimental replications. Letters above the bars indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 (Tukey-Kramer test). (B) The steady state expression level of BrFLCs is associated with days to flower after four weeks of cold treatment. The correlation coefficient between BrFLCs and flowering time score is 0.73 (p < 0.05) and if remove the BRA2209 data (outlier) being 0.91 (p < 0.05).

Variation of the vernalization response in BrFLCs

Of nine B. rapa lines whose flowering time had been measured, two early (RJKB-T02, Homei) and two late flowering (BRA2209, ‘Harunosaiten’) lines were selected to examine the BrFLCs expression in different durations of cold treatments. A decrease in BrFLCs expression levels in response to four weeks of cold treatment was from 15.8% to 47.8%, with the weakest repression observed in BRA2209 (Fig. 5A,B). The rate of repression of BrFLCs expression by four weeks of cold treatment was not related to the expression level of BrFLCs before cold treatment (Fig. 5A,B). BrFLC expression levels after four weeks of cold treatment in BRA2209 and ‘Harunosaiten’ were higher than that in RJKB-T02 and Homei (p < 0.05; Tukey-Kramer test) (Fig. 5A). This difference was related to the difference of flowering time after four weeks of cold treatment (Fig. 1). BrFLCs expression levels were reduced following the cold treatment length in all four lines (Fig. 5A). The rate of decrease in BrFLCs expression level was lowest in BRA2209 (Fig. 5B).

Variation of BrFLC repression by cold treatment. (A) Expression pattern of BrFLCs (BrFLC1 + BrFLC2 + BrFLC3 + BrFLC5) in four B. rapa lines before (NV) and after 4, 6, and 8 weeks of cold treatments (4wkV, 6wkV, and 8wkV, respectively). Y-axis represents the relative expression level of BrFLCs compared to BrACTIN (BrACT). Data presented are the average and standard error (s.e.) from three biological and experimental replications. (B) The ratio of the expression level after cold treatment compared to before cold treatment.

Histone modification spreads at the BrFLC locus upon a return to normal growth conditions after vernalization

We selected two lines (Homei, ‘Harunosaiten’) to examine the relationship between H3K27me3 levels at the BrFLC loci and differences in the vernalization requirements. Homei showed low levels of BrFLCs expression before cold treatment and an early flowering phenotype after four weeks of cold treatment, whereas ‘Harunosaiten’ showed high levels of BrFLCs expression before cold treatment and late flowering phenotype after four weeks of cold treatment (Figs 1 and 5). In both lines, the expression levels of BrFLCs decreased following the four weeks of cold treatment and transcriptional repression was maintained upon return to normal temperature (Supplementary Fig. 12).

At the end of four weeks of cold treatment, H3K27me3 accumulation was observed around the transcription start site (TSS) of BrFLC in both lines. The accumulation of H3K27me3 levels in the region around the TSS was maintained in both lines seven days after returning to normal growth conditions (Fig. 6). In the 5th exon regions, H3K27me3 levels slightly increased, but were lower relative to the TSS in both lines at the end of four weeks of cold treatment (Fig. 6). In both lines, H3K27me3 levels increased seven days after returning to normal growth conditions (Fig. 6); the spreading of H3K27me3 regions in the BrFLC loci was observed in Homei and ‘Harunosaiten’ after seven days of normal growth conditions following four weeks of cold treatment (Fig. 6). The accumulation of H3K27me3 was similar between Homei and ‘Harunosaiten’, suggesting that the level of H3K27me3 at the BrFLC loci does not explain the difference in vernalization requirement between these lines.

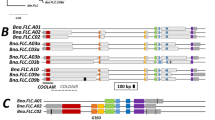

ChIP-qPCR using H3K27me3 antibodies of BrFLC genes before and after four weeks of cold treatment. Upper panel is the gene structure of three BrFLC paralogs. Black boxes represent exon and arrows represent the primer position for ChIP-qPCR. Bottom panel shows the level of H3K27me3 in three BrFLCs before and after four weeks of cold treatment. Y-axis represents the ratio compared to BrSTM, which is an H3K27me3-marked gene. Data presented are the average and standard error (s.e.) from three biological and experimental replications. Statistical tests between NV and 4wkV or between NV and 4wkV + 7d are shown (Student t-test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). NV, non-vernalized; 4wkV, four weeks of cold treatment; 4wkV + 7d, four weeks of cold treatment and then seven days normal growth condition.

Characterization of three functional BrFLC paralogs in BRA2209

We found that the rate of repression of BrFLCs expression by cold treatment was low in BRA2209, and this line showed a high vernalization requirement (Figs 1 and 5). We examined the expression level in each BrFLC paralog in BRA2209 using paralog specific primer sets26. Before cold treatment, BrFLC1 had the highest expression among the four paralogs (Fig. 7). After four weeks of cold treatment, BrFLC1 still had the highest expression level and the suppression rate of BrFLC1 following four weeks of cold treatment was lower than that of other BrFLC paralogs (Fig. 7).

Expression pattern of BrFLC genes in BRA2209 before (NV) and after four weeks of cold treatments (4wkV). Expression level of each BrFLC paralog relative to BrACTIN (BrACT) is calculated. Data presented are the average and standard error (s.e.) from three biological and experimental replications. The ratio of the expression level after cold treatment compared to before cold treatment are shown above the bars. NV, non-vernalized; 4wkV, four weeks of cold treatment.

The sequences of full lengths of the genic regions of BrFLC1, BrFLC2, and BrFLC3 in BRA2209 were determined. In BrFLC1, there was a 410 bp deletion, including part of the 7th exon (31 bp of the 3’ region including stop codon) and a downstream region (Supplementary Fig. 13). Except for two SNPs in the 5th intron, the other exon and intron regions were identical to the reference sequence. There were three SNPs in the 963 bp region upstream of the TSS, and no sequence differences in the 497 bp region downstream from the deleted region in BrFLC1 of BRA2209 (Supplementary Fig. 13). In BrFLC2, there were several substitutions and indels in promoter and intron regions, but no substitutions in the exon regions (Supplementary Fig. 13). In BrFLC3, the promoter region had some sequence differences in comparison to the reference genome and there were some substitutions and indels in the intron regions. However, the coding sequence was identical to the reference genome (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Discussion

High bolting resistance is an important trait for leafy vegetables in B. rapa, and previous reports showed that FLC is a key gene for vernalization2,3. Co-localization of flowering time QTLs with the BrFLC1 or BrFLC2 gene suggests that the loss-of-function of BrFLC causes early flowering2,3. Our study and a previous study revealed that all three BrFLCs function as floral repressors35. The loss-of-function of one of the BrFLC paralogs can result in early flowering, implying that the expression of BrFLC paralogs works to repress flowering in a quantitative manner2,3.

From the reference genome sequence of B. rapa, two BrFRI genes were identified. BrFRIa has three exons and is similar to the functional FRI genes found in other species, while the annotated BrFRIb in the reference genome (BrFRIbΔ) has two exons and appears to be truncated in the C-terminus. As the C-terminus is critical in AtFRI function36, BrFRIbΔ could be non-functional. Indeed, transformation of BrFRIbΔ into the A. thaliana Col accession did not complement the early flowering phenotype. However, we found a third exon by mapping RNA-seq reads against the reference genome. Complementation using this new ORF, termed BrFRIb, confirmed it to be functional, and transformation of BrFRIb into Col delayed flowering. In addition, BrFRIb induced AtFLC transcription and induced AtFLC, which was suppressed by four weeks of cold treatment, indicating that BrFRIb has the same function as AtFRI. We did not find mutations leading to a major defect in the translated protein in any of 37 varieties of B. rapa, and the amino acid sequences of BrFRIa or BrFRIb among these varieties were more than 95% identical. In B. oleracea, BoFRIa has been confirmed to be functional by a complementation experiment32, and has about 88% amino acid sequence identity to BrFRIa, suggesting that BrFRIa is functional. We consider that both BrFRIa and BrFRIb are functional activators of the floral repressor gene FLC in B. rapa.

In our study, the nine lines of B. rapa did not show any positive correlation between the expression levels of the BrFRIs and BrFLCs before cold treatment. These results suggest there is no strong correlation between the expression levels of FRI and FLC before vernalization in the genus Brassica.

There was variation in the flowering time after four weeks of cold treatment among nine lines of B. rapa, suggesting that a cold treatment of four weeks in duration is not saturating for promoting flowering in some lines. In A. thaliana, the variation of flowering time is due to naturally occurring loss-of-function mutations, which have originated independently and result in early flowering accessions (summer annual habit)7,37,38,39,40. It is unlikely that sequence variation in the coding sequences of BrFRIa or BrFRIb influences flowering time variation or the vernalization requirement, because the amino acid sequences are highly conserved and there were no differences in the amino acid sequence between lines showing different flowering times. The absence of an association between BrFRI expression levels and vernalization requirement in this study and the low number of reports showing an association between flowering time QTL and FRI in the genus Brassica41 suggest that the variation of vernalization requirement in B. rapa is not greatly influenced by sequence or transcriptional variation of BrFRI.

All three BrFLCs function as floral repressors; this has been confirmed by other groups in B. rapa35 or B. napus42. These results suggest that we should consider not only each paralogous BrFLC transcript, but also the sum of the three paralogous BrFLC transcripts as an important factor for the vernalization requirement. There is a positive correlation between the expression levels of BrFLC paralogs before cold treatment and the days to flowering after four weeks of cold treatment. This suggests that the expression levels of BrFLC genes before cold treatment may be an indicator of the duration of cold required for vernalization. The rate of suppression of BrFLCs expression by cold treatment was similar among lines except for BRA2209. Generally, if the rate of repression of BrFLC expression is similar among varieties, the expression level before cold treatment is predictive of duration of cold required for vernalization. As a longer cold period will be required to suppress BrFLCs expression in lines having a higher BrFLCs expression prior to cold treatment, the positive correlation between the expression levels of BrFLCs before cold treatment and days to flowering after four weeks of cold treatment supports this idea. However, our experiment assessed nine lines, and we need to verify this possibility by analyzing additional lines.

In BRA2209, expression levels of BrFLCs before cold treatment were not as high as in other lines, but the rate of repression of BrFLCs expression by cold treatment was low, especially of BrFLC1, leading to higher expression levels of BrFLCs after four weeks of cold treatment, consistent with the late flowering phenotype. An extremely late bolting line of B. rapa has a long insertion in the 1st intron of BrFLC2 and BrFLC3, and the rate of decrease in the expression of BrFLC2 and BrFLC3 is low, indicating a weak vernalization response27. We did not identify any sequence difference in the 1st intron of BrFLC1 between BRA2209 and the reference genome. In contrast, we found a 401 bp deletion covering part of the 7th exon and downstream regions in BrFLC1 of BRA2209, suggesting that the 3’ region of BrFLC1 might include a sequence important for the response to prolonged cold.

We have shown that FLC chromatin is enriched with the active histone marks, H3K4me3 and H3K36me3, prior to cold treatment, and that these histone marks are replaced with the repressive histone mark, H3K27me3, during cold exposure22, suggesting that chromatin change is important for the repression of FLC in the vernalization of B. rapa. In A. thaliana, increasing the duration of cold quantitatively enhances the stability of AtFLC repression, and the necessary period of cold treatment varied among accessions. In two different accessions of A. thaliana (FRI Col and Lov-1), the accumulation of H3K27me3 at the entire FLC locus, upon transfer of the plants back to warm conditions after cold treatment, was faster in the accession that requires a shorter period of cold (FRI Col) than in the accession that needs a longer period of cold (Lov-1)43. When treated with four weeks of cold, an enrichment of H3K27me3 was observed around the TSS of the BrFLC loci, but not at the region covering the 5th exon in either line. Upon returning to warm conditions after cold exposure, H3K27me3 accumulation occurred at both TSS and the 5th exon regions in both lines, suggesting that H3K27me3 spreads from the 5’ to 3’ direction in BrFLC genes to maintain FLC repression. The spreading of H3K27me3 in the BrFLC locus is similar to the spreading reported in A. thaliana14,15,43. Unlike the distinct difference in H3K27me3 accumulation reported in A. thaliana, we did not find a difference in the accumulation patterns of H3K27me3 at the BrFLC loci between early and late flowering lines of B. rapa.

Taken together, two factors, the steady state expression levels of BrFLCs and the sensitivity of the repression of BrFLCs by cold treatment, are important for the vernalization requirement in B. rapa. Further study will be required to identify whether variations of these two factors are regulated by cis or trans.

References

Bloomer, R. H. & Dean, C. Fine-tuning timing: natural variation informs the mechanistic basis of the switch to flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 5439–5452 (2017).

Shea, D. J. et al. The role of FLOWERING LOCUS C in vernalization of Brassica: the importance of vernalization research in the face of climate change. Crop Pasture Sci. 69, 30–39 (2018).

Itabashi, E., Osabe, K., Fujimoto, R. & Kakizaki, T. Epigenetic regulation of agronomical traits in Brassicaceae. Plant Cell Rep. 37, 87–101 (2018).

Chouard, P. Vernalization and its relations to dormancy. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 11, 191–238 (1960).

Kim, D. H., Doyle, M. R., Sung, S. & Amasino, R. M. Vernalization: winter and the timing of flowering in plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 25, 277–299 (2009).

Leijten, W., Koes, R., Roobeek, I. & Frugis, G. Translating flowering time from Arabidopsis thaliana to Brassicaceae and Asteraceae crop species. Plants 7, E111 (2018).

Johanson, U. et al. Molecular analysis of FRIGIDA, a major determinant of natural variation in Arabidopsis flowering time. Science 290, 344–347 (2000).

Lee, I. & Amasino, R. M. Effect of vernalization, photoperiod, and light quality on the flowering phenotype of Arabidopsis plants containing the FRIGIDA gene. Plant Physiol. 108, 157–162 (1995).

Michaels, S. D. & Amasino, R. M. FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell 11, 949–956 (1999).

Sheldon, C. C. et al. The FLF MADS box gene: a repressor of flowering in Arabidopsis regulated by vernalization and methylation. Plant Cell 11, 445–458 (1999).

Sheldon, C. C., Rouse, D. T., Finnegan, E. J., Peacock, W. J. & Dennis, E. S. The molecular basis of vernalization: the central role of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 3753–3758 (2000).

Bastow, R. et al. Vernalization requires epigenetic silencing of FLC by histone methylation. Nature 427, 164–167 (2004).

De Lucia, F., Crevillen, P., Jones, A. M. E., Greb, T. & Dean, C. A PHD-polycomb repressive complex 2 triggers the epigenetic silencing of FLC during vernalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16831–16836 (2008).

Finnegan, E. J. & Dennis, E. S. Vernalization-induced trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 at FLC is not maintained in mitotically quiescent cells. Curr. Biol. 17, 1978–1983 (2007).

Angel, A., Song, J., Dean, C. & Howard, M. A Polycomb-based switch underlying quantitative epigenetic memory. Nature 476, 105–108 (2011).

Wang, X. et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat. Genet. 43, 1035–1039 (2011).

Cheng, F. et al. Biased gene fractionation and dominant gene expression among the subgenomes of Brassica rapa. PLoS One 7, e36442 (2012).

Tang, H. et al. Altered patterns of fractionation and exon deletions in Brassica rapa support a two-step model of paleohexaploidy. Genetics 190, 1563–1574 (2012).

Schiessl, S. V., Huettel, B., Kuehn, D., Reinhardt, R. & Snowdon, R. J. Flowering time gene variation in Brassica species shows evolutionary principles. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1742 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and evolutionary analysis of flowering genes in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). BMC genomics 18, 981 (2017).

Schranz, M. E. et al. Characterization and effects of the replicated flowering time gene FLC in Brassica rapa. Genetics 162, 1457–1468 (2002).

Kawanabe, T. et al. Development of primer sets that can verify the enrichment of histone modifications, and their application to examining vernalization mediated chromatin changes in Brassica rapa L. Genes Genet. Syst. 91, 1–10 (2016).

Lou, P. et al. Quantitative trait loci for flowering time and morphological traits in multiple populations of Brassica rapa. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 4005–4016 (2007).

Li, F., Kitashiba, H., Inaba, K. & Nishio, T. A Brassica rapa linkage map of EST-based SNP markers for identification of candidate genes controlling flowering time and leaf morphological traits. DNA Res. 16, 311–323 (2009).

Zhao, J. et al. BrFLC2 (FLOWERING LOCUS C) as a candidate gene for a vernalization response QTL in Brassica rapa. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 1817–1825 (2010).

Kakizaki, T. et al. Identification of quantitative trait loci controlling late bolting in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L.) parental line Nou 6 gou. Breed. Sci. 61, 151–159 (2011).

Kitamoto, N., Yui, S., Nishikawa, K., Takahata, Y. & Yokoi, S. A naturally occurring long insertion in the first intron in the Brassica rapa FLC2 gene causes delayed bolting. Euphytica 196, 213–223 (2014).

Kawamura, K. et al. Genetic distance of inbred lines of Chinese cabbage and its relationship to heterosis. Plant Gene 5, 1–7 (2016).

Fujimoto, R., Sasaki, T. & Nishio, T. Characterization of DNA methyltransferase genes in Brassica rapa. Genes Genet. Syst. 81, 235–242 (2006).

Clough, S. J. & Bent, A. F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743 (1998).

Buzas, D. M., Robertson, M., Finnegan, E. J. & Helliwell, C. A. Transcription-dependence of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation at the Arabidopsis polycomb target gene FLC. Plant J. 65, 872–881 (2011).

Irwin, J. A. et al. Functional alleles of the flowering time regulator FRIGIDA in the Brassica oleracea genome. BMC Plant Biol. 12, 21 (2012).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987).

Shimizu, M. et al. Identification of candidate genes for fusarium yellows resistance in Chinese cabbage by differential expression analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 85, 247–257 (2014).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Delayed flowering time in Arabidopsis and Brassica rapa by the overexpression of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) homologs isolated from Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Plant Cell Rep. 26, 327–336 (2007).

Risk, J. M., Laurie, R. E., Macknight, R. C. & Day, C. L. FRIGIDA and related proteins have a conserved central domain and family specific N-and C-terminal regions that are functionally important. Plant Mol. Biol. 73, 493–505 (2010).

Le Corre, V., Roux, F. & Reboud, X. DNA polymorphism at the FRIGIDA gene in Arabidopsis thaliana: extensive nonsynonymous variation is consistent with local selection for flowering time. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 1261–1271 (2002).

Gazzani, S., Gendall, A. R., Lister, C. & Dean, C. Analysis of the molecular basis of flowering time variation in Arabidopsis accessions. Plant Physiol. 132, 1107–1114 (2003).

Shindo, C. et al. Role of FRIGIDA and FLOWERING LOCUS C in determining variation in flowering time of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138, 1163–1173 (2005).

Méndez-Vigo, B., Picó, F. X., Ramiro, M., Martínez-Zapater, J. M. & Alonso-Blanco, C. Altitudinal and climatic adaptation is mediated by flowering traits and FRI, FLC, and PHYC genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157, 1942–1955 (2011).

Wang, N. et al. Flowering time variation in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) is associated with allelic variation in the FRIGIDA homologue BnaA.FRI.a. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 5641–5658 (2011).

Tadege, M. et al. Control of flowering time by FLC orthologues in Brassica napus. Plant J. 28, 545–553 (2001).

Coustham, V. et al. Quantitative modulation of Polycomb silencing underlies natural variation in vernalization. Science 337, 584–587 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Tomoko Kusumi and Dr. Takahiro Kawanabe for their technical assistance. This work was supported by an Open Partnership Joint Projects of JSPS Bilateral Joint Research Projects, Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (15H04433 & 18H02173) (JSPS) and Hyogo Science and Technology Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T., A.A., E.I., N.N., N.M., H.M., K. Osabe carried out the experiments. D.J.S., M.S. carried out the bioinformatics and statistical analysis of RNA-seq data. R.F., T.T.-Y., T.K., K. Okazaki, E.S.D. planned the experiments. S.T., D.J.S., K. Osabe, T.T.-Y., T.K., K. Okazaki, E.S.D., R.F. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takada, S., Akter, A., Itabashi, E. et al. The role of FRIGIDA and FLOWERING LOCUS C genes in flowering time of Brassica rapa leafy vegetables. Sci Rep 9, 13843 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50122-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50122-2

This article is cited by

-

Dynamic transcriptome analysis provides molecular insights into underground floral differentiation in Adonis Amurensis Regel & Radde

BMC Genomic Data (2024)

-

A transcriptomic time-series reveals differing trajectories during pre-floral development in the apex and leaf in winter and spring varieties of Brassica napus

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Characterization of FLOWERING LOCUS C 5 in Brassica rapa L.

Molecular Breeding (2023)

-

Non-vernalization requirement for flowering in Brassica rapa conferred by a dominant allele of FLOWERING LOCUS T

Theoretical and Applied Genetics (2023)

-

Comparative transcriptome analysis revealed differential gene expression in multiple signaling pathways at flowering in polyploid Brassica rapa

Cell & Bioscience (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.