Abstract

Boron carbide is among the most promising ceramic materials nowadays: their mechanical properties are outstanding, and they open potential critical applications in near future. Since sinterability is the most critical drawback to this goal, innovative and competitive sintering procedures are attractive research topics in the science and technology of this carbide. This work reports the pioneer use of the laser-floating zone technique with this carbide. Crystallographic, microstructural and mechanical characterization of the so-prepared samples is carefully analysed. One unexpected output is the fabrication of a B6C composite when critical conditions of growth rate are adopted. Since this is one of the hardest materials in Nature and it is achievable only under extremely high pressures and temperatures in hot-pressing, the use of this technique offers a promising alternative for the fabrication. Hardness and elastic modulus of this material reached to 52 GPa and 600 GPa respectively, which is close to theoretical predictions reported in literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Boron carbide (B4C) ceramics have been widely considered as high performant ceramic materials thanks to its ultra-high hardness, low density and other promising properties like high elastic modulus, wear resistance and melting point, good thermal stability and somewhat low material cost. This is the reason why boron carbide is the first potential candidate for several structural applications like tribo-component ceramics, nuclear radiation shields, ceramic armours for ballistic protection of both personnel and vehicles1,2,3. It is quite known that the mechanical properties of boron carbide which make it demanding ceramics strongly depend on porosity, composition, microstructure and fabrication process4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Purity is an attractive goal, because pure ceramics normally exhibit optimal mechanical properties and can be studied rigorously due to their reproducibility. In this sense, it is also important from a basic viewpoint because their intrinsic properties (unaltered by additives) are attainable. Therefore, fabrication of pure and near full-dense boron carbide ceramic with retaining its unique properties is the main challenge nowadays. As a main limitation, densification of B4C is rather difficult in the pure state by conventional solid-state sintering methods like pressureless sintering or hot-pressing: in fact, very extreme sintering conditions are required to this purpose1,2. Until now, electric field sintering techniques have been found to be the promising method in general, especially for these hard to-sinter ceramics7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. However, the industrial upscale of the technology is limited due to the reduced size of the samples attainable and the material heterogeneities in large samples and especially the finished cost does not sound reasonable.

The laser floating zone (LFZ) technique is a well-established crystal growth method in materials research, able to produce very high melting point materials with extremely high purity and low cost compared to other advanced techniques. In this method, ceramics grown from melt are found to be near fully dense with fine and homogeneous microstructure. In addition to this, the final pieces present higher potential regarding their mechanical properties20,21. This method is found as a powerful one to grow a long list of oxide ceramics and their composites and eutectics20,21. Recently, boride and carbide eutectic ceramics, specially boron carbide eutectic systems, have been fabricated with this technique with the aim of fabricating hard and high-melting point B4C based ceramics with the properties close to those of pure boron carbide22,23,24. However, there is no attempt to grow a pure and monolithic polycrystalline boron carbide ceramic. This option would thus seem to in principle be more desirable with a view to retaining its intrinsic ultra-high hardness, a largely desired objective for these advanced ceramics.

In this study, we aim to investigate firstly the possibility of fabrication of pure B4C ceramics by laser floating zone technique. Secondly the comprehensive understanding of the microstructure, composition and some preliminary mechanical properties of grown boron carbide with variable growth rates are performed.

Results and Discussion

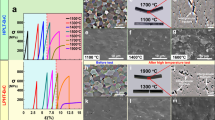

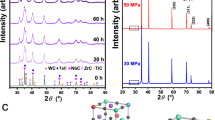

The idealized structure of boron carbide is commonly described as a rhombohedral unit cell that contains one icosahedral B12 unit and one C-B-C chain. The B12 units are composed of crystallographically distinct boron atoms, named as equatorial and polar, in a D3d environment. However, this is an ideal archetype. Due to the wide range of substitutional carbon composition which can be accommodated in the lattice, significant deviations from the idealized model can be found25. In our case, Rietveld refinements of the boron carbide ceramics grown at different velocities are provided in Fig. 1. The crystallographic results after iterative fitting for all samples are displayed in Table 1. Our results show that growth velocity has strong effects on the boron carbide structure and stoichiometry. For low growth rate of 150 mm/h, the structure fits into a model of combination of 73% B11CE icosahedra and 27% B12 icosahedra with chains of C-B-C or C–C. (E stands for “equatorial” position and is a vacancy). 12% vacancies are found in the boron positions of chains and the final stoichiometry is estimated as B4.45C, which is close to the simple structural formula B4C (Fig. 1A). However, a slight increase of boron content and carbon loss is detected at this growth rate. At higher growth velocities, the carbon loss becomes evident and the ceramic approaches to a boron-rich boron carbide structure with the additional presence of some elementary boron. The peaks of this element exhibit a tiny angle difference and overlap with those of boron carbide (Fig. 1B-inset). More precisely, for 300 mm/h growth rate, 51% B11CE icosahedra and 49% B12 icosahedra with chains of C-B-C are the outputs provided by Rietveld analysis (Fig. 1B) which is formulated as B4.98C (~B5C). 22 wt% of elementary boron with the same space group of R \(\bar{3}\) m and rhombohedral cell structure is also detected. At 500 mm/h growth rate, 17% B11CE icosahedra and 83% B12 icosahedra are predicted, with chains composed of C-B-C giving rise to a stoichiometry of B5.91C (~B6C). At this growth rate, the amount of elementary boron increases to 32 wt% (Fig. 1C). This trend of shifting to higher boron-rich boron carbide phase breaks down when the growth rate reaches 750 mm/h. This fact can be inferred from the systematic increase of the lattice parameter with the growth rate until 500 mm/h, which drops for a growth rate of 750 mm/h (Table 1). This is a logical finding due to the difference in the atomic radius between carbon and boron: thus boron-rich boron carbides are expected to have slightly expanded lattice, as reported in literature17,18,25. For 750 mm/h growth rate, the structure fits into a model of again high percentage of B11CP icosahedra (80%) and B12 icosahedra (20%). Now the suffix “P” stands for “polar” position (see Table 1). In this case, the chains are randomly distributed into either C-B-C (81.3%), C-B-B (13.2%) or C-C-C (4.3%) (Fig. 1D). The stoichiometry approaches to B4.36C which again is close to the common B4C formula. The amount of elementary boron is decreased to ~11 wt%. In addition to this, the presence of an ultra-boron-rich boron carbide with formula B10C as a minor second phase is detected. The peaks related to this phase are shown in Fig. 1D-inset and the amount is estimated around 1.31 wt%. In general, no trace of boron oxide or residual carbon is found in any pattern. We tried to find the new theoretically predicted B14C but our fitting is not compatible with their structural parameters and symmetry26.

Figure 2 compares representative FE-SEM images of the B4C ceramics grown at different velocities; the summary of microstructural features is listed in Table 2. At a low growth rate of 150 mm/h that corresponds to the less boron-rich sample (100 wt% B4.45C), equiaxial grains with an average grain size of ~12 µm are found in the centre of the grown rod (Fig. 2A) and there is a border of ~130–150 µm with coarser grains of 37 µm in size (Fig. 2B). The presence of pores is observed in the interior of the grown rod at this growth rate. Contrary to what is expected for directional solidification of ceramics, i.e. the higher growth rate, the finer the microstructure, is not valid in our case and here the microstructure is strongly dependent on boron carbide composition. At the growth rate of 300 mm/h, average grain size in the centre of grown rod reaches to ~19 µm (Fig. 2C), suggesting important grain growth under the influence of the presence of a boron-rich boron carbide of ~B5C with 20 wt% of elementary boron. The grain size in the border grows up to ~61 µm that is a substantial grain growth as well (Fig. 2D). Finer pores are observed in the interior of the grown rod at this growth rate. It is reported before17,18,19, that very low porosity and a remarkable grain growth occurs in boron-rich boron carbide ceramics because of the improvement of bulk diffusion in the presence of additional boron. This tendency continues for higher growth rate of 500 mm/h, thus providing grown rods richer in boron content (~B6C) and higher amount of elementary boron (~32 wt%) and porous-free and average grain sizes in the centre and border estimated to be around 23 µm and 98 µm, respectively (Fig. 2E,F). This is the first time that this elusive phase of boron carbide can be straightforwardly fabricated. Within the uncertainty of our experimental set-up (±50 mm/h), 500 mm/hr is the optimal growth rate for B6C obtention.

Representative FE-SEM micrographs of the boron carbide ceramics grown at (A) 150 mm/h-centre of the rod, (B) 150 mm/h-border of the rod (C) 300 mm/h-centre of the rod, (D) 300 mm/h-border of the rod, (E) 500 mm/h-centre of the rod (F) 500 mm/h-border of the rod (G) 750 mm/h-centre of the rod and (D) 750 mm/h-border of the rod.

At higher grown rate of 750 mm/h, the trend breaks down: the average grain size goes down to ~9 µm and ~24 µm in the centre and border of grown rods, respectively (Fig. 2G,H) and larger pores are found in the microstructure. This is consistent with the composition found for this ceramic, which is recovering a carbon-rich boron carbide structure (~B4.4C). Therefore, diminished grain growth is expected. However, a 11 wt% of metallic boron and the trace of second phase (~1.3 wt%) with highest boron rich boron carbide structure of B10C is detected. In all growth rates, the thickness of border is almost similar (~150–300 µm).

In order to assess the changes in microstructure with growth rate, let us now compare complementary SEM-EBSD results (Fig. 3). In general, for all band contrast maps from EBSD data, the very bright and dark features in the micrographs are pores and shadowing from the grains next to the pores. Planar features/twins are observed in many grains for all velocities. However, there is a higher percentage of planar defects/twins for growth rates of 300 and 500 mm/h which corresponds to boron-rich boron carbide composition (Fig. 3C,E). Our previous results have shown the presence of twins in sintered boron carbide ceramics which controls the kinetics of grain growth13. The dominant role of twins on room temperature27 and high temperature mechanical behaviour of this ceramic28,29 has been proved. More recently, it is reported that boron-rich boron carbides are more disposed to form planar defects during sintering and due at least in part to their lower stacking fault energy which tends to form growth twins19. At this regard, it is important to emphasize that the local composition close to twin boundaries can be altered due to the stress field of this. This is a pending problem out of the scope of this work which deserves studying.

To confirm that the lamella structures observed in the band contrast maps for different velocities and compositions are really twins, the orientations maps from the red rectangular area in Fig. 3 are shown in Fig. 4. The results of misorientation angle across the interfaces for all compositions support that the measured angle for twins is all around 72–73° (Fig. 4B,D,F) that is in good agreement with the known twin relationship in boron carbide30. However, the misorientation of interfaces which correspond to regular grain boundaries are lower or higher than this value.

Respectively, orientation map and the measured misorientation across the interfaces shown by black arrows from the area represented by red rectangular in Fig. 3 for boron carbide ceramics grown at (A,B) 300, (C,D) 500 and (E,F) 750 mm/h.

The analysis of pole figures (see Fig. 5) shows an increasing tendency to texturing: an inspection of the pole figures centred in (0001) shows that normal of planes are progressively more closed to that direction in the reciprocal lattice. Figure 5A shows the poles of higher density, which have been identified and reported in the (0001) zone axis plot. They correspond mostly to low index planes, i.e. planes de high density. In the case of Fig. 5C, the one corresponding to the B6C phase, the texturing is obvious: the longer c axes of grains are aligned along the direction of grown rods, in a columnar growth-type. This increasing tendency correlates with the monotonous increase of the lattice parameters with the growth rate and it breaks down when the growth rate is 750 mm/h and the B10C phase is formed. No dominant texture is detected in the zone axes normal to the (0001). This result is congruent with the preferential crystallographic orientations determined by the March-Dollase approach31. According to this analysis, displayed in Table 1, the orientation of directions increases with the growth velocities, although it decreases slightly for the specimen grown at the highest velocity.

In terms of mechanical properties, hardness and elastic modulus of boron carbide rods grown at variable velocities measured by nanoindentation using a 250 mN load and the results are listed in Table 2. Since all samples have almost ten or more than ten micro-meter grain size, therefore the grain size dependence of hardness is minimized and here the composition of boron carbide has stronger influence on hardness values. For this reason, nano-indentation tests were performed to find the intrinsic hardness for each composition. The results show that increasing the growth rate to 500 mm/h hardness and elastic modulus are increasing to 52 GPa and 600 GPa, respectively, and later at higher velocity of 750 mm/h both parameters drop again to 33 GPa and 450 GPa, respectively. This behaviour can be explained with the change of composition. It means boron-rich boron carbides which contain higher densities of twins and lower porosity get higher hardness and elastic modulus. Furthermore, elementary boron with rhombohedral cell structure also is well-known to have high hardness of around 40 GPa32 which reinforce intrinsic ultra-hard character of boron-rich boron carbide ceramics. High density planar defects have been reported to further improve the hardness of boron-based ceramics33 and specifically boron carbide systems34. Furthermore, ab-initio calculations have also confirmed that the hardness of boron-rich boron carbide with stoichiometry of B6C can reach very high values (48 GPa), much more than conventional B4C (32–35 GPa)35. Regarding the elastic modulus, our results can be compared with those reported by McClellan36 et al. in B5.6C single crystals grown by optical floating zone. Their results show a very high anisotropic Young’s modulus which varies in-between 420–520 GPa. The isotropic elastic modulus derived by the Voigt, Reuss or Hill approximations from the single crystals elastic constants is found to be 460.07 GPa. They are significantly smaller than our results for this quantity. The difference can be related to the different stoichiometry, or more likely, to the strong strengthening induced by twinning in polycrystals29.

Finally, two pieces of consideration must be remarked: the laser-floating zone method, contrary to other successful fabrication methods for boron carbide like SPS, has great practical interest since it can readily be transferred to the ceramics industry due to its potential scalability. On the other hand, this research work opens interesting basic questions: what is the microscopic mechanism driving the formation of such unusual phase? Are there other rare phases accessible through this technique? In the case of boron carbide, one hint which allows a partial response to the first question: according to quantum chemical calculations, boron-rich phases of boron carbide are energetically more stable than those with replacement of boron with carbon25. For sure, laser enhances the tendency to removing carbon, although the detailed mechanism for removal is not known. Information of this mechanism will certainly help to answer the second question. This is for sure the objective of further research in the forthcoming future.

Conclusions

Boron carbide ceramics were grown by the LFZ method with the aim of studying their sinterability, stoichiometry, microstructure and properties. Based on the experimental results and analyses, the following conclusions can be addressed:

-

1.

LFZ is a competitive and efficient technique to fabricate several boron-rich phases of boron carbide ceramics. Moreover, it has been put forth that a careful selection of the processing conditions permits controlling the stoichiometry of this material.

-

2.

A superhard B6C can be fabricated under certain experimental conditions determined in this work. The Young modulus and the nanoindentation hardness are by far the largest ever measured in this material, and very close to the theoretical limit predicted in literature.

Experimental Procedure

The starting materials were commercially available B4C powder (Grade HD20, H. C. Starck, Germany with average particle size around 500 nm). Precursor rods of diameters ~1.8–2 mm and up to 5 cm length were prepared by cold isostatic pressing for 5 min at 200 MPa followed by pre-sintering in a tubular furnace (TermoLab TH1700, Portugal) under a flowing atmosphere of ultra-high purity Ar at 1525 °C for 2 h in order to achieve handling strength.

Boron carbide rods were grown by solidification from the melt using the laser-heated floating zone (LFZ) method with a CO2 laser21. The rods were grown in argon atmosphere and the growth chamber was kept with a slight overpressure of 0.25 bar above ambient pressure in order to avoid the appearance of voids in the solidified rods. A variable growth rate between 150 and 750 mm/h was chosen to evaluate its effect on the composition, stoichiometry, average grain size, hardness of the resulting boron carbide ceramics. A nominal laser output power of ~220 W has been used to maintain a constant feed and very small molten zone. All B4C rods were grown with rotation of the pre-sintered ones with 50 rpm and rods of ~1.3 mm was fabricated.

X-ray powder diffraction patterns were recorded with a Philips X’Pert-Pro diffractometer to analyze the structural changes of grown boron carbide ceramics. In order to determine the crystallographic data and accurate compositions of grown samples in growth rates, Rietveld refinement, using the FullProf program was performed37. The Rietveld method is a mathematical tool which consists of a least square numerical fitting of all the diffraction data of intensities of a diffractogram assuming one structural model as well as several parameters accounting for the experimental set-up. The method is an iterative protocol in which the researcher introduces as an input the space group, lattice parameters and a model of crystal lattice. In this model the tentative position of vacancies is introduced. This mode permits calculating the structure factor, which ultimately is assessed by minimalization of the residual difference between experimental and theoretical values of the diffraction intensities38.

Even though B and C are contiguous in the periodic table, the boron/carbon interchange can be detected unambiguously since it implies the replacement of carbon atoms in 6c by Boron ones in 18 h. In addition to this, the reliability of the detection was assessed thoroughly through PowderCell.

The microstructure was studied in polished cross-sections of grown boron carbide ceramics using the electron images obtained in a field-emission scanning electron microscopy ((FE-SEM) (model Merlin, Carl Zeiss, Germany). The polished surfaces had previously been electro-chemically etched with a solution of 1% KOH. The orientation relationships of grown phases were determined by electron back-scattered diffraction experiments (EBSD). The experiments were performed on polished and non-etched transverse cross-sections using an EBSD system (model HKL from Oxford Instruments, United Kingdom) integrated in a Merlin field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) from Carl Zeiss (Germany). The Channel 5 software was used to index the patterns, build up the orientation maps and obtain the pole figures and orientation relationships39.

Furthermore, nanoindentation tests (Agilent Technologies G200, USA equipped with a Berkovich indentor) at 250 mN with constant loading rate of 0.5 mN/s were done to measure hardness and elastic modulus from loading-unloading curves. The values of hardness and elastic modulus measured by nanoindentor were obtained by average of 30 indentation tests at different positions to minimize the effect of sample surface roughness and grain orientation.

Data Availability

All data are available to the interested researchers on request.

References

Thevenot, F. Boron carbide –a comprehensive review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 6, 205 (1990).

Suri, A. K., Subramanian, C., Sonber, J. K. & Murthy, T. S. R.-C. H. Synthesis and consolidation of boron carbide: a review. Int. Mater. Rev. 55, 4 (2010).

Domnich, V., Reynaud, S., Haber, R. A. & Chhowalla, M. Boron carbide: structure, properties, and stability under stress. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 94, 3605 (2011).

Domnich, V., Gogotsi, Y., Trenary, M. & Tanaka, T. Nanoindentation and Raman spectroscopy studies of boron carbide single crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 3783 (2002).

Chen, M., McCauley, J. W. & Hemker, K. J. Shock-induced localized amorphization in boron carbide. Science. 299, 1563 (2003).

Speyer, R. F., Cho, N. & Bao, Z. Density- and hardness-optimized pressureless sintered and post-HIPed B4C. J. Mat. Res. 20, 2110 (2005).

Ghosh, D., Subhash, G., Sudarshan, T. S., Radhakrishnan, R. & Gao, X. L. Dynamic indentation response of fine-grained boron carbide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 90, 1850 (2007).

Hayun, S., Paris, V., Dariel, M. P., Frage, N. & Zaretzky, E. Static and dynamic mechanical properties of boron carbide processed by spark plasma sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 29, 3395 (2009).

Kim, K. H., Chae, J. H., Park, J. S., Ahn, J. P. & Shim, K. B. Sintering behavior and mechanical properties of B4C ceramics fabricated by spark plasma sintering. J. Ceram. Proc. Res. 10, 716 (2009).

Hayun, S., Kalabukhov, S., Ezersky, V., Dariel, M. P. & Frage, N. Microstructural characterization of spark plasma sintered boron carbide ceramics. Ceram. Inter. 36, 451 (2010).

Moshtaghioun, B. M. et al. Effect of spark plasma sintering parameters on microstructure and room-temperature hardness and toughness of fine-grained boron carbide (B4C). J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 33, 361 (2013).

Moshtaghioun, B. M., Ortiz, A. L., Gómez-García, D. & Domínguez-Rodríguez, A. Densification of B4C nanopowder with nanograin retention by spark-plasma sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 35, 1991 (2015).

Moshtaghioun, B. M., Gómez-García, D. & Domínguez-Rodríguez, A. Exotic grain growth law in twinned boron carbide under electric field. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 38, 4590 (2018).

Ortiz, A. L., Sánchez-Bajo, F., Candelario, V. M. & Guiberteau, F. Comminution of B4C powders with a high-energy mill operated in air in dry or wet conditions and its effect on their spark-plasma sinterability. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 37, 3873 (2017).

Madhav Reddy, K. et al. Enhanced mechanical properties of nanocrystalline boron carbide by nanoporosity and interface phases. Nat. Commun. 3, 1052 (2012).

Cho, N. et al. Densification of carbon-rich boron carbide nanopowder compacts. J. Mat. Res. 22, 1354 (2007).

Roszeitis, S., Feng, B., Martin, H. P. & Michaelis, A. Reactive sintering process and thermoelectric properties of boron rich boron carbide. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 34, 327 (2014).

Cheng, C. H., Reddy, K. M., Hirata, A., Fujita, T. & Chen, M. Structure and mechanical properties of boron-rich boron carbides. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 37, 4514 (2017).

Xie, K. Y. et al. Microstructural characterization of boron-rich boron carbide. Acta. Mater. 136, 202 (2017).

Dhanaraj, G., Byrappa, K., Prasad, V. & Dudley, M. Springer Handbook of Crystal Growth. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (2010).

Llorca, J. & Orera, V. M. Directionally solidified eutectic ceramic oxide. Prog. Mater. Sci. 51, 711 (2006).

Gunjishima, I., Akashi, T. & Goto, T. Characterization of directionally solidified B4C-TiB2 composites prepared by a floating zone method. Mater. Trans. 43, 712 (2002).

Bogomol, I., Nishimura, T., Vasylkiv, O., Sakka, Y. & Loboda, P. Microstructure and high temperature strength of B4C-TiB2 composites prepared by crucibleless zone melting method. J. Alloys. Comp. 485, 677 (2009).

White, R. M., Kunkle, J. M., Polotai, A. V. & Dickey, E. Microstructure and hardness scaling in laser-processed B4C-TiB2 eutectic ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 31, 1227 (2011).

Balakrishnarajan, M. M., Pancharatna, P. D. & Hoffmann, R. Structure and bonding in boron carbide: The invincibility of imperfections. New J. Chem. 31, 473 (2007).

Yang, X., Goddard, W. A. III. & An, Q. Structure and properties of boron-rich boron carbides: B12 icosahedra linked through CBBB Chains. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 2448 (2018).

Moshtaghioun, B. M., Gómez-García, D., Domínguez-Rodríguez, A. & Todd, R. I. Grain size dependence of hardness and fracture toughness in pure near fully-dense boron carbide ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 36, 1829 (2016).

Moshtaghioun, B. M., Gómez-García, D., Domínguez-Rodríguez, A. & Padture, N. P. High-temperature creep deformation of coarse-grained boron carbide ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 35, 1423 (2015).

Moshtaghioun, B. M., Gómez-García, D. & Domínguez-Rodríguez, A. High-temperature deformation of fully-dense fine-grained boron carbide ceramics: experimental facts and modeling. Mater. Des. 88, 287 (2015).

Xie, K. et al. Atomic-level understanding of asymmetric twins in boron carbide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 175501 (2015).

Zolotoyabko. Determination of the degree of preferred orientation within the March-Dollase approach. J. Appl. Crystall. 42, 513 (2009).

Oganov, A. R. & Solozhenko, V. L. Boron: a hunt for superhard polymorphs. J. Superhard Mater. 31, 285 (2009).

Tian, Y. et al. Ultrahard nanotwinned cubic boron nitride. Nature 493, 385 (2013).

An, Q. et al. Superstrength through nanotwinning. Nano Lett. 16, 7573 (2016).

Xia, K. et al. Superhard and superconducting B6C. Mater. Today. Phys. 3, 76 (2017).

McClellan, K. J., Chu, F., Roper, J. M. & Shindo, I. Room temperature single crystal elastic constant of boron carbide. J. Mater. Sci. 36, 3403 (2001).

Rodriguez-Carbajal, J. FULLPROF: a program for Rietveld refinement and pattern matching analysis. In: Abstract of the satellite meeting on powder diffraction of the xv congress of the IUCR, pp. 127 (1990).

Rietveld, H. W. Line profiles of neutron powder diffraction peaks for structure refinement. Acta Crystall 22, 151 (1967).

HKL Technology. Channel 5. Oxford Instrument HKL®. Denmark: HKL Technology (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Government of Spain) and FEDER Funds under Grants Nos MAT2015-71411-R and MAT2016-77769-R. B.M.M. wants to acknowledge the support of the Spanish MINECO by means of a “Juan de la Cierva-Incorporación” fellowship during her sabbatical stay in Zaragoza.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.M.M. designed the experiments. B.M.M. and J.I.P. grew the B4C ceramics by LFZ. F.L.C analyzed X-ray diffraction experiments. B.M.M. and D.G.G. performed microstructural characterization and analysis. B.M.M. performed mechanical tests. B.M.M. and D.G.G. wrote the manuscript with the input from all the other co-authors. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moshtaghioun, B.M., Cumbrera, F.L., Gómez-García, D. et al. Elusive super-hard B6C accessible through the laser-floating zone method. Sci Rep 9, 13340 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49985-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49985-2

This article is cited by

-

Boron-rich boron carbide from soot: a low-temperature green synthesis approach

Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.