Abstract

Climate change threatens coral survival by causing coral bleaching, which occurs when the coral’s symbiotic relationship with algal symbionts (Symbiodiniaceae) breaks down. Studies on thermal adaptation focus on symbionts because they are accessible both in vitro and in hospite. However, there is little known about the physiological and biochemical response of adult corals (without Symbiodiniaceae) to thermal stress. Here we show acclimatization and/or adaptation potential of menthol-bleached aposymbiotic coral Platygyra verweyi in terms of respiration breakdown temperature (RBT) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) enzyme activity in samples collected from two reef sites with contrasting temperature regimes: a site near a nuclear power plant outlet (NPP-OL, with long-term temperature perturbation) and Wanlitong (WLT) in southern Taiwan. Aposymbiotic P. verweyi from the NPP-OL site had a 3.1 °C higher threshold RBT than those from WLT. In addition, MDH activity in P. verweyi from NPP-OL showed higher thermal resistance than those from WLT by higher optimum temperatures and the activation energy required for inactivating the enzyme by heat. The MDH from NPP-OL also had two times higher residual activity than that from WLT after incubation at 50 °C for 1 h. The results of RBT and thermal properties of MDH in P. verweyi demonstrate potential physiological and enzymatic response to a long-term and regular thermal stress, independent of their Symbiodiniaceae partner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reef-building corals are generally distributed in tropical oceans with stable seawater temperatures and low nutrients and make up one of earth’s complicated but highly productive ecosystems1. The success of scleractinian corals in oligotrophic seawater is primarily attributed to their association with dinoflagellate algae1, previously assigned to the genus Symbiodinium and recently changed to family Symbiodiniaceae2. This association is highly sensitive to climate change-induced rising seawater temperatures3. A mere 1~2 °C increase in summer average seawater temperatures coupled with moderate to high irradiance disrupts this symbiotic relationship by expelling the symbiotic algae from the coral host, resulting in so-called coral bleaching4,5. Increased incidences of repeated above-threshold seawater temperature has led to more frequent coral bleaching events covering wider areas—for example, the Great Barrier Reef6 in recent years—further highlighting the threat of thermal impact on coral survival and thus evoking intensive attention to the coral’s ability and mechanisms for adapting to a warming environment.

The mechanisms that underpin coral adaptation to rising temperatures are more complicated than in the other aquatic organisms because of the holobiont nature of corals, wherein in addition to their symbiosis with Symbiodiniaceae, they are also associated with a multitude of other microbes7. Current understanding of how corals respond to thermal stress has shown that at least some species and/or populations have the capacity to acclimatize and/or adapt to warmer conditions by shifting to acquire algal species with a higher thermal tolerability, or by adjusting the physiological performance or genetic structures of coral hosts (for details see the review8 and references therein). Surveys of different Symbiodiniaceae species have also suggested that some of them (e.g., Durusdinium trenchii) are more capable of preventing or repairing photosynthetic damage induced by thermal stress9,10,11,12. Many ecological studies have also confirmed that the resistance of corals to thermal bleaching is highly correlated with the abundance of thermal-tolerant algal species and a greater prevalence of D. trenchii in several bleaching resistant or warm-water symbioses13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 and in some cases prevalence of certain species of Cladocopium (for example, in corals present in Persian/Arabian Gulf23).

Despite the breadth of knowledge on Symbiodiniaceae algae, what we know of how coral hosts respond to thermal stress is derived merely from the studies on coral holobionts (coral + symbionts including bacteria) and non-symbiotic larvae24,25,26,27, but not on aposymbiotic (in this paper this means without Symbiodiniaceae) adult coral colonies due to the lack of an algal-exclusive culture technique. However, several lines of evidence from the studies on coral holobionts have also suggested that coral hosts might respond to heat stress by regulating photo-protective and antioxidant systems4,28, increased heterotrophy29, and symbiont cell densities30, as well as associated bacterial community (see31). Coral hosts are also capable in upregulating the expression of stress-related genes (e.g., heat shock proteins and ROS scavengers) under heat stress24,25,32,33. Given that corals are long-lived organisms, the role of individual acclimatization rather than genetic adaptation was widely expected to play a leading role in their response to global warming24. However, inter-latitudinal crosses of coral parents from warmer and cooler locations clearly demonstrated thermal tolerance of coral is heritable and evolvable25,34,35. In addition, a high correlation between thermal tolerance and genetic changes was observed at a number of loci within the same population of Acropora hyacinthus that inhabited different pools with high and moderate temperature variation and no dispersal barriers in between36. Though genomic evidence strongly supports temperature adaptation in corals, no information has been presented to directly link protein adaptation in coral hosts to thermal stress, which has been widely described in the other aquatic organisms37,38,39,40,41,42.

Temperature is suggested to be a major driving force in evolution43. Accordingly, organisms are expected to adjust their physiological or enzymatic performance to acclimatize and/or adapt to the effects of elevated temperature43. It has been suggested that physiological performance is a powerful approach to examine the evolution of thermal tolerance44. Many studies have demonstrated that respiration performance is a feasible physiological indicator of thermal acclimatization to climate changes in marine invertebrates45, fishes46, plants47 and soil microbes48. Moreover, at the molecular level, enzyme activity is closely linked to metabolic rate and food availability in fishes and marine invertebrates45,46,47,48,49. Temperature adaptation of proteins, especially the enzymes critical to energy metabolism, have been documented in many aquatic ectothermic taxa inhabiting a wide range of thermal habitats37,38,39,40,41,42. Studies have shown that only one or two amino acid substitutions is enough to increase thermal stability in malate dehydrogenase (MDH)42, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)50 or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)51. A recent study52 further demonstrated that protein adaptation to temperature could be quantified by applying a molecular dynamics simulation to analyze the degree of a protein’s structural flexibility.

Herein we demonstrate, in an aposymbiotic coral host (artificially bleached using menthol) its potential physiological and enzymatic response to long-term thermal stress. We compared respiratory physiology and enzyme characteristics of MDH in a menthol-treated aposymbiotic brain coral, Platygyra verweyi53, between a reef located adjacent to a nuclear power plant outlet (NPP-OL, 2~3 °C elevated seawater temperature) and a nearby reef at Wanlitong (WLT) in the Kenting National Park, southern Taiwan. NPP-OL is a natural mesocosm with seawater temperature similar to the scenario forecasted for ocean temperatures in 205025.

Previous studies have shown that the coral assemblage composition in the shallow reef (<3 m in depth) near NPP-OL not only became dominated by stress-tolerant species, but also to had concurrent associations with the tolerant Symbiodiniaceae belonging to D. trenchii.20. Platygyra verweyi is one of the stress-tolerant species associated primarily with D. trenchii (formally type D1a) nearby NPP-OL, and with Cladocopium C3 at WLT54. P. verweyi shows location-based specificity with the type of Symbiodiniaceae genera it associates with19. Studies also have shown that there is no genetic differentiation19,54 between the hosts within and between NPP-OL and WLT in the Kenting National Park, which implies that coral host-symbiont combinations are responsible for coral’s long-term acclimatization and/or adaptation19,51,54. Location-based specificity in association with different symbionts also makes hosts associated with Cladocopium C3 susceptible to bleaching and mortality during prolonged temperature stress54. So, there might be other mechanisms, such as host-specific responses through physiological or enzymatic performance, involved in the local acclimatization and/or adaptation of P. verweyi-symbiont combinations.

Materials and Methods

Study sites, sample collection, and aposymbiotic corals by menthol bleaching

Brain coral, P. verweyi, was sampled at a depth of 2–3 meters from 2 locations; one next to the 3rd nuclear power plant outlet (NPP-OL, 120°44′13″E, 21°56′4″N) and the other at Wanlitong (WLT, 120°41′43″E, 21°59′5″N) in the Kenting National Park, Taiwan. The reef at NPP-OL has experienced 2–3 °C higher seawater temperature than the ambient environment every summer since 1984 due to the operation of the 3rd NPP. In addition, due to the tidally-induced upwelling in Nanwan55, the maximum daily seawater temperature fluctuation at NPP-OL can be more than 8 °C in the summer54. In contrast, WLT, located on the west coast of the Kenting National Park, has an average summer (June to August) seawater temperature similar to NPP-OL, while the intervals of extreme temperature events (≥30 °C) and daily seawater temperature fluctuations are shorter and less extreme than NPP-OL56. Collected corals were acclimated in an aquarium maintained at the conditions as described previously53 for at least 4 days before use.

The menthol-bleaching method53 was used to create aposymbiotic corals. Briefly, small fragments of corals were incubated in 300 ml menthol-supplemented artificial sea water (ASW, Instant Ocean, Aquarium Systems, Sarrebourg Cedex, France). The menthol/ASW medium was prepared by diluting a 20% (w/v) menthol stock (in ethanol) with ASW. Incubation in menthol was ended (at 3 weeks) when the coral was completely bleached (Fig. S1). The bleached coral host samples were used to determine the respiration breaking temperature within a week.

In order to collect enough enzyme for final kinetic analysis, more than 10 runs of purification process were carried out. At each run of purification, nubbins (approximate size = 7 × 7 cm) from 7–8 different colonies were used. Since enzyme kinetic analysis requires large amount of purified enzyme, which is almost not possible for a coral colony to provide, and each purification process is time consuming process, the experiment did not have any biological replicates as well as controls.

Respiration breaking temperature (RBT) of coral host

Aposymbiotic coral nubbins were subjected to heat treatment by incrementally increasing its temperature. Coral nubbins were incubated in a respiratory chamber immersed in a water bath at room temperature for 10 min. Heat treatment was initiated by transferring coral nubbins from room temperature directly into another respiration chamber with preheated (about +2 °C) and aerated artificial seawater (ASW) medium. At each temperature treatment, coral nubbins were incubated for 15 min (5 min for temperature equilibrium and 10 min for oxygen consumption measurement) before being transferred to the next higher temperature treatment. The heating process was ended at 42–43 °C. ASW temperature was measured to 0.01 °C precision with a digital thermometer (TM-907A, Lutron, Taiwan) connected to a thermocouple (TP-100, Lutron, Taiwan). While measuring oxygen consumption, ASW medium in the respiration chamber was mixed with an underwater magnetic stirrer. Changes in oxygen content were measured with an optical dissolved oxygen instrument (YSI ProODO, USA) to avoid electrode polarization, and the signal was channeled to a computer for data collection. RBT was determined by calculating the intercept of two linear regression lines developed respectively from the increase and decrease in respiration rate when the temperature was elevated (Fig. 1A).

Respiration response of aposymbiotic Platygyra verweyi to temperature elevation. (A) An example plot of the changes in respiration rate at different incubation temperatures, in which the respiration breaking temperature (RBT) was determined by the intercept calculated from the linear regression equations of increasing and decreasing respiration rate on temperatures. (B) RBT of the corals collected from a reef near the nuclear power plant outlet (NPP-OL) and an ambient location, Wanlitong (WLT), away from the thermal effluence. The RBT values are shown as mean ± S.D. Numbers of replicated colonies were listed on top of each bar.

Purification of malate dehydrogenase (MDH)

To answer if the differences in thermal sensitivity of respiration physiology between the coral samples from NPP-OL and WLT was linked to the modification of enzymes, MDH, a key enzyme in aerobic energy metabolism in P. verweyi, host tissue extract was analyzed with isozyme composition and Kinetic performance to temperature. MDH was isolated by blasting symbiotic coral with ice-cold ASW and homogenizing the tissue slurry with a hand-held glass tissue grinder. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 4 °C (x15,000 rpm) for 15 min to separate symbiotic algae and tissue debris, then the fraction was collected in 30–80% saturation of ammonium sulfate, re-suspending in 3.2 M (NH4)2SO4 containing 80 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and 0.1 M EDTA, and storing at 4 °C before use.

The isoforms of MDH were examined with a diethylaminoethanol (DEAE) SepharoseTM (Fast Flow, GE healthcare) column (2.6 × 30 cm), and the major MDH fraction was further purified following the modified methods described in57,58. Practically, MDH was purified with a serial column chromatography, including DEAE, CL-6B column, hydroxyapatite, and Sephacryl S-200 column. The detail chromatography condition is described in the supplement. MDH activity in the eluate was measured at 25 °C by adding 50 µl enzyme solution into a substrate solution mixed with 50 µl 3 mM NADH, 50 µl 1 mM oxaloacetate (OAA) and 900 µl 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.0. The enzyme activity was determined by the decrease in 340 nm absorbance recorded by time scanning mode in a spectrophotometer (Hitachi U1900) and standardized with protein concentration determined with Bradford Assay. The changes in 280 nm absorbance and salt concentration of the eluate gradient were determined with a spectrophotometer (Hitachi U1900) and a refractometer, respectively.

SDS-PAGE in 12.5% gel visualized with coomassie blue staining was used to determine the purity and molecular weight of MDH in the Sephacryl S-200 eluate. The molecular weight of native MDH was determined by Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration after comparing with a set of purified protein markers included ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa,) and albumin (66.5 kDa). Protein concentration was determined by a Bradford Assay (Bio-Rad Protein Assay, Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Effects of temperature on enzyme kinetic parameters and stability

The enzyme reaction was determined as described in the purification section, except that OAA concentration was varied from 14 to 29 μM with a fixed NADH concentration (3 mM) to determine OAA’s substrate concentration (Km) and saturating substrate concentration (Vmax), and NADH varied from 38 to 95 µM with a fixed OAA concentration (1 mM) to determine NADH’s Km and Vmax. All reaction rates were obtained from the mean of triplicate reactions. The reaction temperature in the cuvette was maintained using a water jacket cuvette holder connected to a thermostatic bath (YIH DER, BL-720). Prior to each thermodynamic analysis, a digital thermometer was used to confirm temperature stability in the cuvette three times when mixing 100 µl substrate, 50 µl enzyme and 900 µl buffer (maintained in a thermostatic bath at the reaction temperature).

Obtained Vmax values were further used to calculate the activation energy required for MDH catalysis (Eacat) and that for inactivating MDH activity (Eainact) by temperature with the Arrhenius equation. Eacat and Eainact values were usually used to evaluate the thermostability of enzymes in different organisms. The Eacat was determined by plotting natural-logarithmically (ln) transformed Vmax on T−1 in °K, in which the Vmax data were obtained from pre-optimum temperature. The Eainact was calculated by plotting the ln-transformed inactivation rate constants k on T−1 in °K. The k values were determined by subtracting each Vmax obtained at the post-optimum temperature from the Vmax at optimum temperature and converted to per second. The fitness of the kinetic data to the Arrhenius equation, [ln (Vmax or k) = ln(A) − (Ea/R)(1/T)], was examined by a linear regression of ln(Vmax or k) against T−1 (R = 8.314 J mol−1 °K−1).

The thermal stability of MDH isolated from NPP-OL and WLT coral samples were compared by incubating the diluted enzyme solution (in 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.0) containing activity of about 20 nmol min−1 at 50 °C for 60 min. Residual activities of MDH in percentages were determined with the ratio of MDH activity at each time interval compared to the original. Triplicate measurements of enzyme activity at every time interval were made under the condition described in the purification section.

Statistical analysis

Respiration performances of P. verweyi coral hosts between NPP-OL and WLT were compared with a Student’s t-test. Differences in the slopes of linear regression of ln(Vmax), ln(Km) and ln(k) on temperature in °K were analyzed by Minitab statistical software.

Results

Thermal experience shapes the response of coral host respiration to temperature

The respiration rate of aposymbiotic P. verweyi initially rose linearly when incubation temperature was increased, but started to decrease at higher temperature when reaching the RBT (Fig. 1A). All datasets showed high regression coefficient r2 values, 0.970 ± 0.024 (mean ± SD, N = 10) and 0.982 ± 0.018 (N = 16) for NPP-OL and WLT respectively. The mean RBT of P. verweyi from NPP-OL samples was 36.7 ± 1.4 °C (mean ± SD, N = 5), which was significantly higher than the 33.6 ± 2.0 °C (N = 8) from WLT (t11 = 2.9153, P < 0.05, df = 11) (Fig. 1B).

MDH chromatography pattern and purity

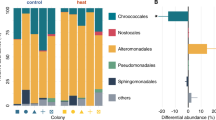

Both NPP-OL and WLT samples displayed a consistent profile that contained only two MDH fractions (Fig. 2). The two MDH fractions could not be further separated using a linear gradient of different NaCl concentrations (data not shown). Thus, only the major MDH isozyme (peak II) which contained >75% of total activity was collected for further purification. MDH in the DEAE eluate from both NPP-OL and WLT samples displayed only one peak and almost identical elution conditions in the following Sepharose CL-6B, hydroxyapatite and Sephacryl S-200 column chromatographies (Figs S2–S4). In the Sephacryl S-200 gel chromatography, the MDH activities of both NPP-OL and WLT samples were eluted synchronously with A280 absorbance, indicating that the enzymes had been highly purified at both sites. MDH purity in the Sephacryl S-200 eluate was estimated to be >90% by SDS-PAGE and coomassie blue stain, as shown in Fig. S4, and only one clear band was visualized at about 39 kDa for the NPP-OL sample and 38 kDa for the WLT one. With calibration to standard proteins by Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration (Fig. S5), the molecular weight of the native MDH form was about 67 kDa and 64 kDa for the NPP-OL and WLT samples, respectively, indicating that the major MDH of P. verweyi was a typical dimer. Finally, the overall purification process described above increased the specific MDH activities from about 2 µmol min−1 mg−1 in the tissue extract to 77 (from NPP-OL) and 111 µmol min−1 mg−1 (from WLT) in the Sephacryl S-200 eluates; these purified enzyme solutions were used for further kinetic analysis at the different temperatures.

Enzyme kinetics and thermal susceptibility

The apparent Km and Vmax of MDH varied around 27 °C for the samples from NPP-OL and WLT; this was 7.5 and 12.7 µM for the Km of NADH, 9.4 and 5.7 µM for the Km of OAA, 24.6 and 22.9 nmol min−1 for the Vmax of NADH, and 31.2 and 28.9 nmol min−1 for the Vmax of OAA. When the reaction temperature rose, the Arrhenius plot with ln(Vmax) on T−1 in °K showed a linear increase and then decrease at some higher temperatures, as shown in Fig. 3. The data’s fitness to linear regression model and regression parameters are described in Table S1. According to the intersection of the Arrhenius plot in Fig. 3, samples from NPP-OL performed at a 4.7~10.6 °C higher optimum temperature than those from WLT, depending on substrates. However, the activation energy for MDH catalysis (Eacat), calculated from the data in Fig. 3, were as shown in Table 1 for the Eacat of OAA and NADH, respectively, and did not display significant differences between the two sampling locations (P > 0.05). When plotting ln(Km) for temperature in T−1 (°K) (Fig. S6), Km initially displayed a linear increase, but, different from the performance of Vmax in Fig. 3, came to a plateau after the optimum temperature. Therefore, the sensitivity of Km to rising temperatures was examined with the data sets obtained from pre-optimum temperatures. The Km dataset’s fitness to linear regression model and regression parameters are described in Table S2. In Fig. 4, the slopes of the MDH Km values did not differ significantly between sites (P > 0.05), regardless of whether they were plotted with ln(Km) on T−1 (°K) or Km on T (°C) (in inset), implying that samples from NPP-OL and WLT had comparable temperature sensitivities.

Effect of temperature on the apparent Km of pre-inactivated malate dehydrogenase from Platygyra verweyi at pH 7.0. Conditions for determining apparent Km of pre-inactivated malate dehydrogenase are described as in Fig. 3. Results obtained with various OAA concentrations are shown in (A) and NADH are shown in (B). Results displayed in degree C are also shown in the inset.

The activation energy for thermal inactivation (Eainact) and the enzyme stability at 50 °C were investigated to further compare the differences in thermal sensitivity of MDH between NPP-OL and WLT. Eainact of MDH was determined with the Arrhenius plot of ln(k) on T−1 (°K), as shown in Fig. 5, in which all four data sets fit the linear regression model well (see regression parameters and coefficients in Table S3). MDH displayed significantly different slopes between NPP-OL and WLT for both substrates (Fig. 5, P < 0.05). Calculated Eainact indicated that MDH from NPP-OL samples required almost two times higher activation energy to inactivate the enzyme than MDH from WLT, as shown in Table 1. When MDH was incubated at 50 °C, the enzyme activity of the samples from WLT decreased with time faster than that of samples from NPP-OL, as shown in Fig. 6. Moreover, residual activity for the MDH from NPP-OL samples was 64 ± 9% (mean ± S.D., n = 3), which was nearly two times higher than that from WLT (32 ± 2%).

Arrhenius plot for thermal inactivation of malate dehydrogenase from Platygyra verweyi at pH 7.0. Conditions for determining apparent Vmax of malate dehydrogenase are described as in Fig. 3. Inactivation rate constant k was determined by subtracting the Vmax at each incubation temperature post enzyme inactivation from the Vmax at optimum temperature and converting it to per second.

Thermal stability of malate dehydrogenase in Platygyra verweyi at pH 7.0. Malate dehydrogenase (ca. 20 nmol min−1) obtained from Sephacryl S-200 eluate, as described in Fig. S3, was incubated in a 50 °C water bath for 1 h, and residual enzyme activities were determined periodically.

Discussion

This study clearly demonstrates that coral hosts have the potential to acclimatize and/or adapt physiologically and enzymatically to long-term thermal stress. The 3rd nuclear power plant, operating since 1984, has been discharging thermal effluent from the outlet (NPP-OL), resulting in 2.0–3.0 °C warmer summer water temperatures in the adjacent reef compared to other nearby reefs, such as WLT. The RBT of aposymbiotic Platygyra verweyi in NPP-OL was also nearly 3.0 °C higher than that in WLT, suggesting that coral hosts in NPP-OL, despite the high percentage of individuals that associate with thermal-tolerant Durusdinium spp20, might have also physiologically adapted and/or acclimatized after being impacted by the consistent warmer SST for over 30 years. The critical temperature RBT (also named Arrhenius Breaking Temperature, ABT43) for the mitochondria of aquatic organisms is shown to be highly correlated with their maximum habitat or acclimation temperature, and the species adapted to warmer temperatures would perform the RBT closer to that temperature43. Consistent with the other aquatic organisms, the higher RBT values in aposymbiotic P. verweyi from NPP-OL than from WLT might be a response to the variation in local temperature between two conspecific populations.

Results of MDH bioassays provide some insights, although preliminary, into the protein adaptations that underpins performance differences between the thermal physiologies of Platygyra verweyi collected from different temperature regimes. Results clearly indicated that MDH of P. verweyi from NPP-OL was more thermally stable than that from WLT. The kinetic analyses showed that the MDH isolated from P. verweyi in NPP-OL displays a 4.7 or 10.6 °C higher optimum temperature and 1.8 fold higher Ea of thermal inactivation than that from WLT, depending on substrates. In addition, the MDH of P. verweyi from NPP-OL showed 2 times higher residual activity than that from WLT after 1 h at 50 °C. When the enzyme’s adaptation to temperature was examined, the ligand affinity as measured by apparent Michaelis–Menten constants (Km) was usually modified to respond to environmental temperatures38,40,41,42,44,51,59,60. The MDH was also proposed to be functionally and structurally more sensitive to temperature perturbation than another ATP-generating related enzymes in mussels50. However, Km’s responses to temperature were comparable between the purified P. verweyi MDH in NPP-OL and that in WLT. Consistent with the response of Km to temperature, the catalytic Ea of MDH from P. verweyi in NPP-OL was not significantly different from that of WLT samples. When the Vmax of MDH from P. verweyi in NPP-OL was calculated from the equations derived from Fig. 3 with the optimum temperature of that from WLT (42.4 and 38.4 °C for that of NADH and OAA, respectively), the results indicated that the Vmax values were very close between two sites (NPP-OL/WLT: 50/53 and 91/97 for NADH and OAA, respectively). A study on Antarctic notothenioid fish showed that A4-lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) decreased activation energy and substrate affinity (i.e., increase in Km) for adapting to cold temperature51, this suggests that, in order to provide comparable Vmax by balancing between stability and flexibility, adaptation to temperature might be achieved by modifying enzyme structure to increase Km and decrease catalytic Ea. Similar to the response of Km to temperature, catalytic Ea and Vmax at the same temperature between the MDH from NPP-OL and WLT samples suggest that higher thermal resistant performance in the MDH from NPP-OL than WLT samples might not be attributed to temperature adaptation mechanisms described in the literature6,40,41,42,44,51,59,60.

Second, configuration analysis also indicated that the genes coding the MDH of Platygyra verweyi may be different from those in published studies in other marine invertebrates50,59. Both MDH samples from NPP-OL and WLT consistently showed two distinct MDH fractions with about 25 and 75% of total activity, according to the DEAE profile, suggesting that the different respiration physiology performances might not be attributed to the variations between the two fractions. In addition, only one MDH isoform was obtained in the sample from NPP-OL and WLT, respectively, when the major MDH fraction (peak II) was purified. The purified MDH from both sites were all in the dimer form. In current available coral genome60,61, Stylophora pistillata contains two MDH isoforms with very similar monomer molecular weights (33.6 and 36.1 kDa) within at least 4 MDH genes61. However, the genome data could not manifest if these monomers were constructed into dimer as found in the MDH sample from P. verweyi. Although in the literature, MDH adaptation was shown to be achieved with 1 or 2 amino acid mutations. A nearly 1 kDa difference in MDH molecule between that from NPP-OL and WLT might be attributed to two alternative possibilities. One possibility is acclimatization scenario with 2 MDH enzymes with very similar molecular weight, but with different thermal stability in the P. verweyi from NPP-OL and WLT. Another possibility is adaptation scenario in which MDH from NPP-OL contains roughly 9 amino acid mutations compared to that from WLT. The proposed hypothesis can be tested through direct protein sequencing or cloning the target gene for further DNA sequencing. At present, we do have analysis carried out using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and this information will be using in the future studies to clone MDH gene for further sequencing. Therefore, genetic analysis of the genes encoding the MDH should be conducted before we can conclude whether MDH genes of P. verweyi from NPP-OL already show signs of acclimatization and/or adaptation.

Even though changes in the algal symbiont from thermal sensitive to tolerant genotypes (e.g., Durusdinium sp.) were highlighted as a potential mechanism of coral acclimatizing to high temperature15,24, the species compositions of corals in NPP-OL were dramatically changed with long-term exposure to high temperatures and concurrent associations with tolerant Durusdinium spp20. P. verweyi is one of few coral species in NPP-OL that has not only survived, but prospered19. If the more thermally stable MDH isoform found in NPP-OL inhabiting P. verweyi was a result of selection from the regular thermal stress in the summer, would it be possible to acclimatize a population in WLT to survive in NPP-OL? Reciprocal transplantations of P. verweyi between NPP-OL and WLT54 suggest that heating period duration was also important to the P. verweyi survival rate when transplanted from WLT to NPP-OL. We conducted two reciprocal transplantations in April of 2014 and 2015 so the transplanted corals could have 3~4 months to acclimatize to the warmer water occurring in the summer. The results of the transplantation indicated that the survival rates of P. verweyi transplanted from WLT to NPP-OL depends highly on the duration of the warm period54. If the accumulating heat stress is prolonged beyond a threshold—for example, 10.43 degree of heating week (DHW)—P. verweyi would barely survive, even if shuffled from the thermally liable symbiont to stress tolerant D. trenchii54. Conversely, the NPP-OL colonies transplanted to WLT displayed a higher growth rate than conspecific NPP-OL and WLT native populations. Therefore, in order to understand how coral will adapt to changing climate and increased occurrences of high seawater temperatures, it is important to resolve the puzzle involving mechanisms behind aposymbiotic coral host acclimatization and/or adaptation, symbiont population dynamics and its contribution to coral stress response and the duration of heating period. To completely understand if a given coral species can survive the intensity and duration of temperature stress, insights from aposymbiotic host mechanisms will pay way for a better understanding of the nature of stress resistance and contribution to the same from the coral host perspective.

Data Availability

All additional data from the experiment are provided in “Supplementary Materials”.

References

Knowlton, N. The future of coral reefs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 5419–5425 (2001).

LaJeunesse, T. D. et al. Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 28, 1–11 (2018).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. In press. IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P. R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds)]. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 32 pp.

Fitt, W. K., Brown, B. E., Warner, M. E. & Dunne, R. P. Coral bleaching: interpretation of thermal tolerance limits and thermal thresholds in tropical corals. Coral Reefs 20, 51–65 (2001).

Lesser, M. P. & Farrell, J. H. Exposure to solar radiation increases damage to both host tissues and algal symbionts of corals during thermal stress. Coral Reefs 23, 367–377 (2004).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature 556, 492–496 (2018).

Rohwer, F., Seguritan, V., Azam, F. & Knowlton, N. Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 243, 1–10 (2002).

Hoey, A. S. et al. Recent advances in understanding the effects of climate change on coral reefs. Diversity 8, 12 (2016).

Tchernov, D. et al. Membrane lipids of symbiotic algae are diagnostic of sensitivity to thermal bleaching in corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13531–13535 (2004).

Takahashi, S. et al. Different thermal sensitivity of the repair of photodamaged photosynthetic machinery in cultured Symbiodinium species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3237–3242 (2009).

McGinty, E. S. et al. Variations in reactive oxygen release and antioxidant activity in multiple Symbiodinium types in response to elevated temperature. Microb. Ecol. 64, 1000–1007 (2012).

Krueger, T. et al. Antioxidant plasticity and thermal sensitivity in four types of Symbiodinium sp. J. Phycol. 50, 1035–1047 (2014).

Baker, A. C. Reef corals bleach to survive change. Nature 411, 765–766 (2001).

Fabricius, K. E., Mieog, J. C. & Colin, P. L. Identity and diversity of coral endosymbionts (zooxanthellae) from three palauan reefs with contrasting bleaching, temperature and shading histories. Mol. Ecol 13, 2445–2458 (2004).

Berkelmans, R. & van Oppen, M. J. H. The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: a ‘nugget of hope’ for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 273, 2305–2312 (2006).

Mieog, J. C. et al. Real-time PCR reveals a high incidence of Symbiodinium clade D at low levels in four scleractinian corals across the Great Barrier Reef: implications for symbiont shuffling. Coral Reefs 26, 449–457 (2007).

Jones, A. M. et al. Community change in the algal endosymbionts of a scleractinian coral following a natural bleaching event: Field evidence of acclimatization. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 1359–1365 (2008).

Silverstein, R. N., Correa, A. M. S. & Baker, A. C. Specificity is rarely absolute in coral-algal symbiosis: implications for coral response to climate change. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 279, 2609–2618 (2012).

Keshavmurthy, S. et al. Symbiont communities and host genetic structure of the brain coral Platygyra verweyi, at the outlet of a nuclear power plant and adjacent areas. Mol. Ecol 21, 4393–4407 (2012).

Keshavmurthy, S. et al. Can resistant coral-Symbiodinium associations enable coral communities to survive climate change? A study of a site exposed to long-term hot water input. PeerJ 2, e327 (2014).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Ecologically differentiated stress-tolerant endosymbionts in the dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae) clade d are different species. Phycologia 53, 305–319 (2014).

Boulotte, N. M. et al. Exploring the Symbiodinium rare biosphere provides evidence for symbiont switching in reef-building corals. ISME J. 2693–2701, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2016.54 (2016).

Hume, B. C. C. et al. Symbiodinium thermophilum sp. nov., a thermotolerant symbiotic alga prevalent in corals of the world’s hottest sea, the Persian/Arabian Gulf. Sci. Rep. 5, 8562, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08562 (2015).

Palumbi, S. R., Barshis, D. J., Traylor-Knowles, N. & Bay, R. A. Mechanisms of reef coral resistance to future climate change. Science 344, 895–898 (2014).

Dixon, G. B. et al. Genomic determinants of coral heat tolerance across latitudes. Science 348, 1460–1462 (2015).

Bellantuono, A. J., Hoegh-Guldberg, O. & Rodriguez-Lanetty, M. Resistance to thermal stress in corals without changes in symbiont composition. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 279, 1100–1107 (2012).

Polato, N. R. et al. Location-specific responses to thermal stress in larvae of the reef-building coral Montastraea faveolata. PLoS One 5, e11221 (2010).

Linan-Cabello, M. A. et al. Seasonal changes of antioxidant and oxidative parameters in the coral Pocillopora capitata on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Mar. Ecol. 31, 407–417 (2010).

Grottoli, A. G., Rodrigues, L. J. & Palardy, J. E. Heterotrophic plasticity and resilience in bleached corals. Nature 440, 1186–1189 (2006).

Cunning, R. et al. Dynamic regulation of partner abundance mediates response of reef coral symbioses to environmental change. Ecology 96, 1411–1420 (2015).

Shiu, J.-H. et al Dynamics of coral-associated bacterial communities acclimated to temperature stress based on recent thermal history. Sci. Rep. 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14927-3 (2017).

Barshis, D. J. et al. Genomic basis for coral resilience to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1387–1392 (2013).

Kenkel, C., Meyer, E. & Matz, M. Gene expression under chronic heat stress in populations of the mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides) from different thermal environments. Mol. Ecol. 22, 4322–4334 (2013).

Kirk, N. L., Howells, E. J., Abrego, D., Burt, J. A. & Meyer, E. Genomic and transcriptomic signals of thermal tolerance in heat-tolerant corals (Platygyra daedalea) of the Arabian/Persian Gulf. Mar. Ecol. 27, 5180–5194 (2018).

Manzello, D. P. et al. Role of host genetics and heat-tolerant algal symbionts in sustaining populations of the endangered coral Orbicella faveolata in the Florida Keys with ocean warming. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 1016–1031 (2018).

Bay, R. A. & Palumbi, S. R. Multilocus adaptation associated with heat resistance in reef-building corals. Curr. Biol. 24, 2952–2956 (2014).

Place, A. R. & Powers, D. A. Genetic variation and relative catalytic efficiencies: lactate dehydrogenase B allozymes of Fundulus heteroclitus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 76, 2354–2358 (1979).

Fields, P. A. & Somero, G. N. Hot spots in cold adaptation: localized increases in conformational flexibility in lactate dehydrogenase A4 orthologs of Antarctic notothenoid fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95, 11476–11481 (1998).

Fields, P. A. et al. Temperature adaptation in Gillichthys (Teleost: Gobiidae) A4 lactate dehydrogenases: identical primary structures produce subtly different conformations. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 1293–1303 (2002).

Johns, G. C. & Somero, G. N. Evolutionary convergence in adaptation of proteins to temperature: A4-lactate dehydrogenases of Pacific damselfishes (Chromis spp.). Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 314–320 (2004).

Fields, P. A., Rudomin, E. L. & Somero, G. N. Temperature sensitivities of cytosolic malate dehydrogenases from native and invasive species of marine mussels (genus Mytilus): sequence-function linkages and correlations with biogeographic distribution. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 656–667 (2006).

Dong, Y. & Somero, G. N. Temperature adaptation of cytosolic malate dehydrogenases of limpets (genus Lottia): differences in stability and function due to minor changes in sequence correlate with biogeographic and vertical distributions. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 169–177 (2009).

Hochachka, P. W. & Somero, G. N. Biochemical Adaptations. (Oxford: Oxford University Press) (2002).

Somero, G. N. The physiology of climate change: how potentials for acclimatization and genetic adaptation will determine ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 912–920 (2010).

Stillman, J. H. Acclimation capacity underlies susceptibility to climate change. Science 301, 65 (2003).

Pörtner, H. O. Climate change and temperature-dependent biogeography: oxygen limitation of thermal tolerance in animals. Naturwissenschaften 88, 137–146 (2001).

Atkin, O. K. & Tjoelker, M. G. Thermal acclimation and the dynamic response of plant respiration to temperature. Trend Plant Sci 8, 343–351 (2003).

Crowther, T. W. & Bradford, M. A. Thermal acclimation in widespread heterotrophic soil microbes. Ecol. Lett. 16, 469–477 (2013).

Dahlhoff, E. P. Biochemical indices of stress and metabolism: applications for marine ecological studies. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 66, 183–207 (2004).

Lockwood, B. L. & Somero, G. N. Functional determinants of temperature adaptation in enzymes of cold- versus warm-adapted mussels (genus Mytilus). Mol. Biol. Evol. 10, 3061–3070 (2012).

Fields, P. A. & Houseman, D. E. Decreases in activation energy and substrate affinity in cold adapted A4-lactate dehydrogenase: evidence from the Antarctic notothenioid fish Chaenocephalus aceratus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 2246–2255 (2004).

Dong, Y.-W. Structural flexibility and protein adaptation to temperature: Molecular dynamics analysis of malate dehydrogenases of marine molluscs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, 1274–1279 (2018).

Wang, J.-T. et al. Physiological and biochemical performances of menthol-induced aposymbiotic corals. PLoS ONE 7(9), e46406 (2012).

Kao, K.-W. et al. Repeated and prolonged temperature anomalies negate Symbiodiniaceae genera shuffling in the coral Platygyra verweyi (Scleractinia; Merulinidae). Zool. Stud. 57, 55 (2018).

Lee, H.-J., Chao, S.-Y., Fan, K.-L., Wang, Y.-H. & Liang, N.-K. Tidally induced upwelling in a semi-enclosed basin: Nan Wan Bay. J Oceanogr 53, 467–480 (1997).

Hsu, C.-M. et al. Temporal and spatial variations in symbiont communities of catch bowl coral Isopora palifera (Scleractinis: Acroporidae) on reefs in Kenting National Park, Taiwan. Zool. Stud. 51, 1343–1353 (2012).

Tayeh, M. A. & Madigan, M. T. Malate dehydrogenase in phototrophic purple bacteria: purification, molecular weight, and quaternary structure. J. Bacteriol. 169, 4196–4202 (1987).

Yueh, A. Y., Chung, C.-S. & Lai, Y.-K. Purification and molecular properties of malate dehydrogenase from the marine diatom Nitzschia alba. Biochem. J. 258, 221–228 (1989).

Fields, P. A., Dong, Y., Meng, X. & Somero, G. N. Adaptations of protein structure and function to temperature: there is more than one way to ‘skin a cat’. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 1801–1811 (2015).

Cunning, R. et al. Comparative analysis of the Pocillopora damicornis genome highlights role of immune system in coral evolution. Sci. Rep 8, 16134 (2018).

Voolstra, C. R., Li, Y. & Liew, Y. J. Comparative analysis of the genomes of Stylophora pistillata and Acropora digitifera provides evidence for extensive differences between species of corals. Sci. Rep 7, 17583 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Mr. Noah Last for editing the manuscript for English editing. This research was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 104-2621-B-127 -001 -MY3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T.W. and C.A.C. conceived the experimental design. J.T.W., S.K. and C.A.C. developed the idea and wrote the manuscript. Y.T.W. conducted the experiment. P.J.M. was involved in developing the idea and all technical support.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, JT., Wang, YT., Keshavmurthy, S. et al. The coral Platygyra verweyi exhibits local adaptation to long-term thermal stress through host-specific physiological and enzymatic response. Sci Rep 9, 13492 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49594-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49594-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.