Abstract

After hatching, juveniles of most sea turtle species undertake long migrations across ocean basins and remain in oceanic habitats for several years. Assessing population abundance and demographic parameters during this oceanic stage is challenging. Two long-recognized deficiencies in population assessment are (i) reliance on trends in numbers of nests or reproductive females at nesting beaches and (ii) ignorance of factors regulating recruitment to the early oceanic stage. To address these critical gaps, we examined 15 years of standardized loggerhead sighting data collected opportunistically by fisheries observers in the Azores archipelago. From 2001 to 2015, 429 loggerheads were sighted during 67,922 km of survey effort. We used a model-based approach to evaluate the influence of environmental factors and present the first estimates of relative abundance of oceanic-stage juvenile sea turtles. During this period, relative abundance of loggerheads in the Azores tracked annual nest abundance at source rookeries in Florida when adjusted for a 3-year lag. This concurrence of abundance patterns indicates that recruitment to the oceanic stage is more dependent on nest abundance at source rookeries than on stochastic processes derived from short term climatic variability, as previously believed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Knowledge of a species’ abundance and demography is essential for population assessment and designing effective conservation strategies. However, understanding demographic processes is challenging, especially for species with complex life histories that involve large scale migrations (e.g. tuna1; sharks2,3; whales4; seabirds5; and sea turtles6). The loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) is a good example of a highly migratory species with a complex life cycle characterized by successive ontogenetic habitat shifts from terrestrial habitats where nesting and embryonic development occur to developmental and foraging habitats in the open ocean and, later, in neritic waters7,8,9,10. Loggerhead sea turtles are distributed throughout tropical and temperate regions worldwide and, for management purposes, are subdivided into nine distinct population segments (DPS), which are classified as either threatened or endangered11. Age at sexual maturity for males and females is about 36 to 42 years12.

Of all loggerhead sea turtle life stages, the post-hatchling and oceanic juvenile stages are the least understood8. Oceanic-stage juveniles generally occur in low densities over vast oceanic areas9,13, which strongly hampers their study. As a consequence, the abundance and demography of oceanic-stage juveniles are poorly known, and population models continue to rely heavily on a set of assumptions regarding critical parameters (e.g. stage-specific survival rates, for details14). Trends in abundance of sea turtle populations have relied almost entirely on counts of nesting females and/or the nests they deposit10. In the Northwest Atlantic loggerhead population, sexual maturity is reached after 36–38 years in females12. Thus, any changes in abundance in juvenile stages as a result of new sources or intensities of mortality such as from marine pollution and fisheries15,16, will not be recognized until that age class reaches sexual maturity and arrives at the nesting beach. The importance of monitoring population trends of oceanic-stage juveniles as part of an “early warning system” – as we do for the first time in this paper – has been identified as a high priority10,17,18,19,20.

A key life-history transition is that of recruitment from nesting beaches to the oceanic juvenile stage. This transition is thought to be associated with high mortality (19–51%13,21,22,23,24) and encompasses several demographic processes and potential hazards such as nest destruction, hatchling emergence success, hatchling and neonate survival, and dispersal patterns driven by ocean currents7. These processes could be either density-dependent or -independent and could have a large stochastic component10. With this complexity in mind, we considered two basic and contrasting recruitment scenarios to characterise this transition, recognizing that reality may lie somewhere in between: (i) stable recruitment, with a recruitment rate that is a constant, predictable function of nest production in source rookeries, and (ii) variable recruitment, with a recruitment rate that is highly variable, dependent on stochastic events, and therefore largely unpredictable. Under stable recruitment, nest production is the main driver determining the number of individuals that enter the oceanic juvenile stage, and fluctuations in survival throughout this transition are small. Variable recruitment suggests a transition that is determined by largely stochastic processes, which can conceivably be linked to environmentally mediated mortality and survival rates. Sweepstakes recruitment is a particular example of this latter mechanism in which a small and often changing proportion of the population successfully contributes to the replenishment of the entire population in each year under influence of environmental stochasticity25. Such sweepstake effect has been reported in sea urchins26, sardines and anchovies27 and may exist in West Atlantic green turtles28.

Contemporary population models for Northwest Atlantic loggerheads rely heavily on nest counts in the source rookeries, and assume minimal variation in annual survival rates within the oceanic realm and therefore relatively stable recruitment from oceanic to neritic habitats after approximately the first decade of life14,29. These assumptions have been challenged by recent modeling studies that inferred a predominantly variable recruitment determined by highly variable neonate survival under influence of climate forcing30,31. The lack of empirical data on the abundance and recruitment of oceanic juveniles has so far precluded assessing these contrasting hypotheses directly, despite the fundamental importance for conservation planning.

The Azores archipelago is an important feeding and developmental ground for oceanic-stage loggerhead sea turtles9,13,32. Genetic work has revealed that the loggerheads found here mainly belong to the Northwest Atlantic DPS and originate from the southeastern United States (90%33,34) namely in Florida, one of the two largest nesting aggregations of loggerheads in the world35. Between late June and early November each year, loggerhead hatchlings with a curved carapace length (CCL) of about 5 cm emerge from approximately 1500 km of nesting beaches from Florida to North Carolina36 and enter the sea to be dispersed into the North Atlantic Gyre by the Gulf Stream9,32. In the Azores, recorded sizes of loggerhead sea turtles range from 8.5 to 82 cm CCL13 and the duration of the oceanic juvenile phase is estimated to average between 9 to 12 years37,38. These juveniles are primarily epipelagic9 and appear to actively explore the vicinity of seamounts and peaks39, which are common features in the region40.

Since 2001, the Azores Fishery Observer Program (POPA - Programa de Observação das Pescas dos Açores) has collected sighting data under a standardised protocol to document the occurrence of loggerhead sea turtles during operations of the pole and line tuna fishery. Based on these data, the objectives of the present study were (1) to present the first time series of relative abundance of oceanic juvenile stage loggerhead sea turtles in the North Atlantic; and (2) to assess the correlation with contemporary nest counts from the major source rookeries to investigate whether recruitment to the oceanic juvenile stage is stable or variable. The results will allow us to evaluate the use of opportunistic platforms to monitor low density aggregations such as oceanic juvenile stage loggerheads.

Methods

Study area

The Azores archipelago comprises nine volcanic islands divided into three groups (eastern, central and western) separated by deep waters (>2000 m). Shallow waters (<600 m) cover <1% of the almost 1 million km2 of the Azorean EEZ. The region is largely dominated by two eastward flows originating from the Gulf Stream: the cold North Atlantic Current in the North, and the warm Azores Front/Current system to the South. Mean sea surface temperature varies between 15 to 20 °C in winter and 20 to 25 °C in summer.

Survey design

The data were collected under the Azorean Fisheries Observer Program (POPA; www.popaobserver.org) and consisted of dedicated visual transects for sea turtles, which were performed following a fixed protocol by fishery observers on-board pole-and-line tuna vessels41. The pole-and-line tuna fleet operated in the Azores between May and November and was subject to observer coverage of 50–100%. The data consisted of 15-minute visual transects which were performed up to 6 times a day (every 2 hours, i.e. at 09:00, 11:00, 13:00, 15:00, 17:00 and 19:00). Transects had no predetermined track and were only performed when the vessels were travelling or searching for tuna, and when weather conditions were favourable (i.e. sea state < 6 Beaufort). Sea turtle sightings were recorded from the flying bridge, approximately 8 m above sea level, on both sides of the vessel. Observers were equipped with Bushnell Marine binoculars (7 × 50) with integrated compass and a GPS device. Sighting angle (°) was calculated from the recorded compass heading of the vessel (°N) and the sighting (°N), while distance (m) from the vessel was estimated visually. At the beginning and at the end of each transect, observers recorded geographic location, time, sea and weather conditions (sea state – Beaufort scale, glare and visibility). Weather conditions were estimated using a categorical scale following standard POPA procedures. All observers received an intensive 10-day training before being deployed.

Data filtering

The database covered the period from 2001 to 2015 and contained 22,341 transects (Fig. 1) and 515 turtle sightings. The great amount of data generated by this methodology is counterbalanced by one obvious limitation: the lack of experimental design inherent to this opportunistic methodology results in an unbalanced spatial and temporal coverage that is driven by the fishing activity. The data were cleaned and subsequently filtered in order to reduce the effect of the sampling bias using the following steps: 1) transects were filtered using the distance between the beginning and end point to obtain credible, semi-linear transects with lengths ranging between 1.35 and 5.40 km, corresponding to average vessel speeds between 5.40 and 21.60 km h−1, respectively; 2) transects conducted with sea conditions above 3 Beaufort were discarded42,43; and 3) kernel density estimation with reference bandwidth selection was used to eliminate spatial outliers using the 95% area contour44.

Map of the study area showing locations of the standardised line transects performed between 2001 and 2015 by fishery observers from the Azores Fishery Observer Program (POPA - Programa de Observação das Pescas dos Açores) onboard pole-and-line tuna vessels before (top panel) and after (bottom panel) filtering. The black line shows the 95% Kernel area contour for the filtered data. The dashed line shows the 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone.

Environmental data

Environmental variables used in the analysis were expected to influence the distribution of loggerheads (e.g.45). In addition to the four environmental factors that were recorded by the observers at the time of observation (Beaufort sea state, glare, visibility and the time of day), we included eight environmental factors: depth, seabed slope, distances to the coast (DcoastKm), to the 500 m (D500Km) and to the 1000 m (D1000Km) isobaths, sea surface temperature (SST), net primary productivity (NPP) and sea surface height deviation (SSHd). Depth was available at a 0.0027 degree grid cell resolution and was derived from acoustic bathymetric data analyzed in Vasquez et al.46. Slope, DcoastKm, D500Km and D1000Km were calculated from these bathymetric data using ESRI ArcGIS 10.1, and were included to indicate proximity to topographic features like seamounts and oceanic islands. Remote sensing data products (SST, NPP and SSHd) were obtained from NOAA’s Coast Watch program (http://coastwatch.pfeg.noaa.gov/). Daily SST was obtained at 0.25 degree grid cell resolution from the Reynolds Optimum Interpolation V2 high-resolution blended analyses, which used data from the NOAA National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR). Monthly averaged NPP (in mg C m-2 day-1) was obtained at 0.1 degree grid cell resolution, and was calculated from Chlorophyll-a concentration and photo-synthetically available radiation (PAR) measured by the SeaWiFS sensor and SST measurements from the NOAA Pathfinder Project. Daily SSHd was a merged product from various altimetric missions (Topex/Poseidon, ERS-1/2, Geosat Follow-On, Envisat and Jason-1) and was provided by Aviso at a 0.25 degree grid cell resolution. SSHd was included to indicate meso-scale phenomena such as eddies. Loggerhead sea turtle counts were spatially allocated to the average geographic position of each transect, and intersected with environmental data. Besides these environmental variables we also included latitude and longitude in the models to account for unexplained spatial variance. To evaluate the effect of time of day, we created a categorical variable in which the six daily periods were divided into three groups (09:00 and 11:00: morning; 13:00 and 15:00: midday and 17:00 and 19:00: afternoon).

Probability of detection

The detection probability of loggerhead sea turtles during transects was estimated using conventional (CDS) and multiple-covariate distance sampling (MCDS)47,48,49.

After a preliminary analysis of the distance data, smearing was applied to the recorded sighting angles and distances to account for rounding errors resulting from the visual estimation, so called heaping47,48. Uniform smearing was applied over the sector defined by the angle range (Ө − ф, Ө + ф) and distance range (r*(1 − s), r*(1 + s)), where Ө and r are the measured angle and distance to the sighting, ф is the smearing angle and s is the proportional sector of distance to use as the basis for smearing. Since the observed angle and distance distributions showed marked spikes at 10-degree and 10-meter intervals respectively, smear parameters were set to ф = 5° angle and s = 0.2 m distance. Perpendicular distance of the sightings to the transect line was calculated as d = r*sin θ47. Data truncation was applied at 100 m in order to eliminate outliers and improve model fitting48, resulting in a strip width of 200 m.

Hazard-rate and half-normal detection functions with null, cosine and polynomial adjustments were fitted to the perpendicular distance data (n = 429 detections) grouped into distance bins (0–5, 5–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50 and 50–100 m), along with covariates that could influence the detection of turtles (Beaufort sea state, glare and vessel speed). Best model fit was selected using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and the final model fit was assessed using diagnostic plots and goodness-of-fit chi-square test50. All analyses were performed using the “Distance” package in R51.

Data analysis

Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs) were used to relate the density of loggerheads with topographic, environmental and spatially explicit variables in order to derive an unbiased index of relative abundance for the study area between 2001 and 2015. Such approach is particularly useful for surveys from opportunistic platforms, when the survey design cannot be randomised52,53. The density of loggerhead sea turtles was modelled using the number of loggerheads sighted as the response variable and the logarithm of the effective area surveyed (i.e. transect length x strip width x sighting probability) as offset term53,54. Candidate explanatory variables consisted of the year, vessel speed and the environmental variables. The observer ID was included as a random effect to account for any observer effect, whereas inclusion of vessel ID did not improve the models. Sightings were modelled as count data assuming a zero-inflated Poisson distribution (ZIP-GAMM), because Poisson and negative binomial distributions were shown to impose incorrect assumptions on the data. Data examination revealed a high proportion of zero counts (98%, n = 17419) and the distribution was over-dispersed (i.e. variance > mean) compared to the traditional Poisson distribution (i.e. variance = mean). ZIP models were considered appropriate for the data, because a ZIP distribution allows for over-dispersion and calculates relative abundance as a mixed process with binary and Poisson distributions55. Through model selection, one-stage zero-inflated Poisson models (ziP link function in mgcv56) were shown to outperform two-stage models (ziplss link function in mgcv56). The GAMM models were built by backward selection of individual smooth terms and tensor product smooths. Model selection was based on information criteria (AIC) because model parameters were fitted using penalized likelihood maximization (gam function from the mgcv package56). To reduce chances of overfitting, the number of knots of the smoothers were adjusted whenever appropriate. Nested models were compared using significance testing (Chi-square test). Model assumptions were evaluated through the inspection of diagnostic plots. Annual estimates of relative abundance were derived from the model estimates for each year. All analyses were performed in R57.

Nonparametric bootstrap (“boot” package in R58) was used to estimate the true variance in the annual estimates of relative abundance obtained from the models53,54. Both the detection function and GAMM were refitted for each of 1000 new datasets which were resampled from the original data, with replacement and independently for each year. The bootstrap standardised errors (BSE) of the annual estimates are reported, while the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles were used as the 95% confidence intervals (BCI), making no assumptions about the underlying distribution53,54.

To explore the relationship between model estimates of relative abundance for the Azores and nest counts from Florida core index beaches (FCIB, data courtesy of S. Ceriani, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Index Nesting Beach Survey Program Database as of 25 Sept. 2016) the model derived annual estimates of relative abundance were lag-plotted against annual nests counts for 0- to 12-year lags and the cross-correlation calculated using the astsa package for R59.

Results

Data filtering

After filtering, the dataset consisted of 17,761 transects covering 67,992 km within a 95% kernel core area of 198,401 km2. This dataset contained sightings of 429 loggerheads that were recorded along 393 transects (Fig. 1). Details on the number of transects and sightings retained for analysis per filtering step and per year are summarized in supplementary material (Table S1). The mean annual number of transects included in the analysis over the 15 yr. was 1184.1 (SD ± 361.5) for a mean annual effort of 4528.14 km (SD ± 1338.02) and mean transect length of 3.82 km (SD ± 0.87). The dataset further showed some considerable variability in the number and spatial distribution of transects in relation to the different years and months (supplementary material Figs S1–S2).

Probability of detection

The detection function with lowest AIC was the hazard-rate function with null adjustment and with Beaufort sea state as a covariate. The average probability of detection per transect was 0.148 (±0.020 SE) and varied between 0.113 (Beaufort 2) and 0.274 (Beaufort 0) according to Beaufort sea state (Fig. 2). The chi-square value of the goodness of fit test was marginally significant (p = 0.03) owing to a lack of observations between 5 and 10 m, but was not deemed sufficient to prevent using the model for inference.

Observed distances and fitted detection function for loggerhead sea turtles during visual line transects performed between 2001 and 2015 by fishery observers from the Azores Fishery Observer Program (POPA - Programa de Observação das Pescas dos Açores) onboard pole-and-line tuna vessels. The line shows the average detection function, while the points represent the estimates in function of the Beaufort sea state.

Data analysis

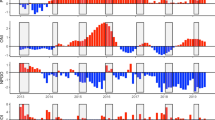

The results of the final ZIP-GAMM are summarized in Table 1. The independent variables that were retained after model selection and validation were year, time of day, sea state, SST and distance to the coast. The model explained approximately 75.6% of the variability. Plots of the partial effects of the different covariates are included in Figs 3 and 4. The model showed a strong effect of sea conditions on the observed density of loggerhead sea turtles, i.e. an increase with decreasing sea state measured in Beaufort. The effect of SST displays a strong negative trend over the range from 18° to 25 °C. The relationship with distance to coast indicates a lower density of sea turtles up to approximately 10 km from the coast line. For the influence of time of day, the model shows higher values during midday relatively to morning and afternoon periods.

GAMM generated partial effects of Beaufort sea state (top left), Time of day (top center), distance from the coast (top right) and SST (bottom left) on the density of loggerhead sea turtles in the Azores calculated from the POPA visual sightings database (2001–2015). The QQ-plot (bottom right) shows the Gaussian quantiles of the observer effect.

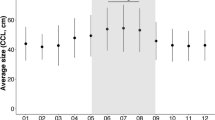

GAMM derived annual indices of relative abundance (Ind./0.1 km2; ±BSE) of loggerhead sea turtles in the Azores calculated from the POPA visual sightings database (2001–2015), compared with annual nest counts from Florida core index beaches (Index Nesting Beach Survey - Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission; 1998–2012). The X-axis shows the year of the POPA sightings, matched with the year from the annual nest counts from Florida core index beaches in parentheses, assuming a 3-year lag. Blue – POPA visual sightings; Grey - annual nest counts from Florida core index beaches.

The analysis further revealed a significant effect of year on the relative abundance of loggerheads (Fig. 4). The relative abundance of loggerhead sea turtles in the Azores region declined 67% (18%–84% BCI) from 0.0689 Ind./0.1km2 (±0.0277 BSE) in 2001 to 0.0229 Ind./0.1km2 (±0.0106 BSE) in 2009. From 2012 to 2015 the relative abundance increased 342% (87%–801% BCI) to 0.0808 Ind./0.1km2 (±0.0289 BSE). This pattern showed a very close correspondence when lag plotted against the annual nest counts from Florida core index beaches (Fig. 4). Lag-analysis showed the highest cross-correlation (r = 0.82) for a 3-year lag between nest counts and the modelled relative abundance based on sightings from Azorean tuna vessels (Fig. 5; Supplementary material Fig. S3). While the lagged relative abundance in the Azores generally tracked annual nest counts very closely (e.g. 2008 and 2012), despite some evident departures such as for the years 2010 and 2014, it is important to note that such correlation does not establish a causal relationship.

Panel A: Cross-correlation between the GAMM derived annual relative abundance of loggerhead sea turtles in the Azores calculated from the POPA visual sightings database (2001–2015), and annual nest counts from Florida core index beaches (Index Nesting Beach Survey - Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission; 1989–2015) for 0 to 12 year lags. Panel B: Lagged scatter plot for a 3-year lag (astsa package in R) of the GAMM derived annual index of relative abundance of loggerhead sea turtles in the Azores (2001–2015), versus annual nest counts from Florida core index beaches (1998–2012).

Discussion

This study provides the first assessment of relative abundance of oceanic-stage juvenile sea turtles. Based on 15 years of standardised visual transects performed on opportunistic platforms, this study provides important information for this key life stage for which little demographic information is currently available. Since Archie Carr’s landmark study on the “lost year(s)”32, the importance of the Azores for the Northwest Atlantic loggerhead population has been extensively studied and documented9,13,33,36,37,3860. However, this is the first study to establish a quantitative link in addition to the already established genetic link33,34 between oceanic-stage juvenile loggerheads in the archipelago and source rookeries 5000 km away.

The model revealed the existence of a strong effect of the year on the relative abundance of loggerhead sea turtles in the study area and a close correspondence with the pattern of nest counts in source rookeries in Florida. Nest counts recorded on Florida core index beaches displayed a dramatic decline by 43% between 1998 and 2006 and have been recovering since61. Concurrently, relative abundance of oceanic juvenile stage loggerheads displayed a lagged response with a 67% (18%–84% BCI) decrease and subsequent increase. Besides this general trend, it appears that even smaller oscillations in relative abundance (e.g. 2008 and 2012) were predictable based on nest counts from corresponding years. We therefore conclude that the relative abundance of oceanic juvenile stage loggerheads was largely driven by the production of nests in the source rookeries and that recruitment was largely stable during the studied period.

The effect of climate forcing on demographic processes in sea turtles has received considerable emphasis, in particular its influence on sex determination62,63, nest distribution64, nesting activity65,66,67 and growth rates68,69,70. A possible link between declining annual nest counts of loggerheads in the Northwest Atlantic and the observed environmental regime shift, which was responsible for declining growth rates in three Atlantic sea turtle species70, has also been hypothesised and still requires further evaluation68. Alternatively, recent modelling studies have proposed a strong effect of historical climate forcing on neonate survival, mediated through oceanic current dynamics, to explain trends in annual nest counts30,31. However, the latter mechanism implies a highly variable neonate survival30,31 and consequently a variable recruitment to the open ocean, which would be expected to offset the observed correlation between nest abundance and the relative abundance in the open ocean. Hence, it appears unlikely that population growth has depended decisively on variable, climate-mediated survival during the first year of life30,31. Our study thus provides empirical evidence for the key assumption of minimal variability in survival rates during the early oceanic stage which supports contemporary conservation planning for Northwest Atlantic loggerhead sea turtles.

Overall, stochastic effects appear to be less important than would be expected based on their influence on individual processes such as nest destruction, hatching and emergence success, and dispersion by ocean currents71,72,73,74,75. Variable recruitment has been extensively documented for marine invertebrates and fish species with productive, r-selected life histories76,77,78,79,80, as opposed to loggerhead sea turtles, which are long-lived, late maturing organisms with low fecundity29. Although neonates are largely inactive, low energy, float-and-wait foragers9,43,81, potential behavioural plasticity between active and passive behaviours in early juveniles may further contribute to their resilience against environmental fluctuations9,82.

The 3-year lag between nest counts and abundance estimates in the Azores corresponds approximately to the age of loggerheads with 25 cm CCL12,36, which is in line with the observed detection size of sea turtles from Azorean tuna vessels13,60. The reported age distribution assessed between 1990 and 1992 in the Azores showed that approximately 50% (between 43% and 60% for individual years) of the individuals sampled on pole-and-line tuna vessels were between 2 and 4 years of age13, so that a 3-year lag seems justified. Nevertheless, further analysis and contemporary characterization of the demography in terms of age distribution and origin will be necessary to fully reconcile the presence of multiple age classes in the Azores and the close correspondence with nest counts from Florida core index beaches.

Our model was able to explain a large proportion (75.6%) of the variability in the sighting data. Since the effect of sea conditions on the detection probability was adjusted for in the detection function, the environmental variables that were retained were likely either linked to availability (time of day, Beaufort sea state and SST) and habitat characteristics (SST and distance to coast). Availability for detection depends on the time sea turtles spend at the surface, and is likely influenced by the time of day and the sea state. Surface behaviour of oceanic-stage loggerheads satellite tagged off Madeira was shown to vary seasonally, was more frequent during the day, particularly during spring and summer, and was positively associated to conditions favouring absorption of solar radiation, such as low wind and elevated air temperature83. The decreasing number of observed loggerheads with SST higher than 18 °C is consistent with satellite tracking data in the North Pacific84. This negative trend in function of SST in combination with its range and low resolution suggests a seasonal effect, with a higher observed density during spring compared to summer. While this seasonal pattern can be related to availability bias83, it also challenges the concept of a closed population during the tuna fishing season. Juvenile loggerheads are known to display wide ranging movements83,85,86, including in the study area87, but seasonal dynamics remain poorly understood and will require further investigation.

Some variables that were expected to influence the relative abundance were not retained during model procedures (e.g., latitude and longitude), or could not be included because of issues with collinearity (e.g., NPP). The spatial and temporal scales considered in the present study are an important factor and may not coincide with those on which we expect certain environmental variables and drivers to act (e.g., SSHd as proxy for meso-scale features45,84,85,87). For example, the variables that served as proxy for the presence of seamounts (i.e. slope, distance to the 500 m and 1000 m isobaths) were not retained, notwithstanding previously reported associations39. One of the reasons may be the high density of seamounts in the area in combination with their different levels of attraction to oceanic visitors and the variable scale of their influence radius88, which are likely to obscure their effects. Similarly, the effect of nest counts on the relative abundance is more likely to be detected when nest productivity itself undergoes significant change, as is the case for the Northwest Atlantic population. Longer time series are undoubtedly necessary to fully understand regulatory mechanisms and the effect of long-term climate forcing on recruitment.

Even though departures from the relationship with nest counts (e.g., 2010 and 2014) may be simply due to a lack of accuracy of the estimates, alternative explanations may relate to a low number of transects (e.g. 2014), variation in fisheries operations (e.g. 2010 and 2014), and/or possible distributional range shifts due to climate forcing (e.g. 2010). The years 2010 and 2014 were anomalous in terms of the tuna fisheries in the region. The year 2010 was characterized by an exceptional capture of skipjack tuna, by far the highest in the last 12 years, and an extension of the fishing season until November, whereas an average season ends towards the end of September89. In 2014, tuna landings in the Azores were the lowest in the last decade and consequently vessels operated mostly outside the Azores EEZ. In addition, the scarcity of tuna influenced boat captains to adapt their fishing operations (e.g., deep hand-lining with live bait and FAD-style concentration of fish under the vessel). Together, these operational changes resulted in a much lower number of visual transects (~−40%). The winter of 2009/2010 was also characterized by an exceptionally negative phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which was responsible for anomalous low SSTs in the central North Atlantic that were noticeable for several months90,91,92. Given the strong influence of SST on loggerhead distribution and behaviour (e.g.93,94,95,96), it is likely that the higher than expected relative abundance was also linked to some climate driven shift in distributional range or habitat compression80,97, as reported for pelagic fish such as sardines and anchovies98.

The present study corroborates the adequacy of standard visual sightings from opportunistic platforms as a useful tool for assessing the relative abundance of juvenile oceanic stage loggerhead sea turtles. The method allows for a sufficiently high sighting effort necessary to assess this low density life stage. This is particularly relevant due to the importance of sea state variables on detectability and availability, since suitable sea conditions can be a limitation. The filtered dataset represents a cumulative 4440.25 hours of visual sighting effort, or 296.02 hours/yr (SD ± 90.38). A dedicated annual survey with comparable effort, seasonal and spatial coverage is usually not feasible due to financial and logistical constraints. Simultaneous data collection on multiple platforms by fisheries observers represents a valid alternative as it allows sharing resources with fishery observer programs, which are often mandatory, and achieving a broad spatial coverage. In contrast, its dependence on fishing activity can be a limitation for consistent and long term monitoring, when fishing operations or fishery monitoring obligations change.

Continued monitoring of oceanic juvenile stage loggerheads is critical. Current assessment of loggerhead sea turtle populations relies too heavily on abundance estimates of nesting females10. Our study demonstrates that monitoring the oceanic juvenile stage can provide an additional assessment stage in the long life cycle of loggerheads, allowing the detection of population disturbances during the first years of life (“early warning system”), either from anthropogenic or natural causes. Further improvements of the assessment can be expected through the generation of credible estimates of absolute abundance for the area47,48. This progress depends on the verification of the method’s assumptions and the quantification of availability bias, which is linked to surface behaviour and mediated by environmental variables99. Obtaining reasonable and reliable absolute abundance estimates would be an important step, as it would allow a more thorough interpretation of mortality from by-catch or other anthropogenic threats.

Data Availability

Sea turtle sighting data from the Fisheries Observer Program of the Azores POPA41 are accessible through the OBIS (http://www.iobis.org/) and EMODnet (http://www.emodnet-biology.eu/) open access repositories.

References

Block, B. A. et al. Electronic tagging and population structure of Atlantic bluefin tuna. Nature 434, 1121–1127, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03463 (2005).

Vandeperre, F., Aires-da-Silva, A., Lennert-Cody, C., Santos, R. S. & Afonso, P. Essential pelagic habitat of juvenile blue shark (Prionace glauca) inferred from telemetry data. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 1605–1625, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10321 (2016).

Vandeperre, F. et al. Movements of blue sharks (Prionace glauca) across their life history. PLoS ONE 9, e103538, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103538 (2014).

Silva, M. A., Prieto, R., Jonsen, I., Baumgartner, M. F. & Santos, R. S. North Atlantic Blue and Fin Whales Suspend Their Spring Migration to Forage in Middle Latitudes: Building up Energy Reserves for the Journey? PLoS ONE 8, e76507, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076507 (2013).

Montevecchi, W. A. et al. Tracking seabirds to identify ecologically important and high risk marine areas in the western North Atlantic. Biol. Conserv. 156, 62–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.12.001 (2012).

Hays, G. C. & Scott, R. Global patterns for upper ceilings on migration distance in sea turtles and comparisons with fish, birds and mammals. Funct. Ecol. 27, 748–756, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12073 (2013).

Chaloupka, M. Y. Stochastic simulation modelling of southern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population dynamics. Ecol. Model. 148, 79–109, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(01)00433-1 (2002).

Bolten, A. B. Variation in sea turtle life history patterns: neritic vs. oceanic developmental stages. In The Biology of Sea Turtles, vol. II (eds Lutz, P. L., Musick, J. A. & Wyneken, J.) 243–257, Boca Raton, FL,https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420040807.ch9 (2003).

Bolten, A. B. Active swimmers – passive drifters: the oceanic juvenile stage of loggerheads in the Atlantic system. In Loggerhead Sea Turtles (eds Bolten, A. B., Witherington, B. E.) 63–78, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press (2003).

National Research Council (Committee on the Review of Sea Turtle Population Assessment Methods). Assessment of Sea-Turtle Status and Trends Integrating Demography and Abundance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/12889 (2010).

NOAA-NMFS. Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta): NOAA Fisheries http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/turtles/loggerhead.html (2017).

Avens, L. et al. Age and size at maturation and adult stage duration for loggerhead sea turtles in the western North Atlantic. Mar. Biol. 162, 1749–1767, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-015-2705-x (2015).

Bjorndal, K. A., Bolten, A. B. & Martins, H. R. Estimates of survival probabilities for oceanic-stage loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in the North Atlantic. Fish. Bull. 101, 732–736 (2003).

Conant, T. A. et al. Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) 2009 status review under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Silver Spring: Loggerhead Biological Review Team, National Marine Fisheries Service (2009).

Wallace, B. P. et al. Impacts of fisheries bycatch on marine turtle populations worldwide: toward conservation and research priorities. Ecosphere 4, 40, https://doi.org/10.1890/ES12-00388.1 (2013).

Pham, C. K. et al. Plastic ingestion in oceanic-stage loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) off North Atlantic subtropical gyre. Mar. Pollut. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.06.008 (2017).

Turtle Expert Working Group. Assessment Update for the Kemp’s Ridley and Loggerhead Sea Turtle Populations in the Western North Atlantic. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS- SEFSC-444, Southeast Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2000).

Turtle Expert Working Group. 2009 An Assessment of the Loggerhead Turtle Population in the Western North Atlantic Ocean. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS SEFSC-575, South- east Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2009).

Bjorndal, K. A. et al. From crisis to opportunity: Better science needed for restoration in the Gulf of Mexico. Science 331, 537–538, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199935 (2011).

OSPAR, OSPAR Recommendation 2013/7 on furthering the protection and conservation of the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) in Regions IV and V of the OSPAR maritime area. OSPAR Commission, source OSPAR(2) 13/4/1, Annex 10 (2013).

Crouse, D. T., Crowder, L. B. & Caswell, H. A stage-based population model for loggerhead sea turtles and implications for conservation. Ecology 68, 1412–1423, https://doi.org/10.2307/1939225 (1987).

Heppell, S. S., Crowder, L. B., Crouse, D. T., Epperly, S. P. & Frazer, N. B. Population models for the Atlantic loggerhead. In Loggerhead Sea Turtles (eds Bolten, A. B. & Witherington, B. E.) 255–273, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press (2003).

Sasso, C. R., Braun-McNeill, J., Avens, L. & Epperly, S. P. Effects of transients on estimating survival and population growth in juvenile loggerhead turtles. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 324, 287–292, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps324287 (2006).

Sasso, C. R. & Epperly, S. P. Survival of pelagic juvenile Loggerhead turtles in the open ocean. J. Wildl. Manage. 71, 1830–1835, https://doi.org/10.2193/2006-448 (2007).

Hedgecock, D. Does variance in reproductive success limit effective population sizes of marine organisms? In Genetics and Evolution of Aquatic Organisms (ed. Beaumont, A. R.) 122–134 (Chapman & Hall 1994).

Flowers, J. M., Schroeter, S. C. & Burton, R. S. The recruitment sweepstakes has many winners: genetic evidence from the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Evolution 56, 1445–1453, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01456.x (2002).

Grant, W. S. & Bowen, B. W. Shallow Population Histories in Deep Evolutionary Lineages of Marine Fishes: Insights From Sardines and Anchovies and Lessons for Conservation. J. Hered. 89, 415–426, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/89.5.415 (1998).

Bjorndal, K. A. & Bolten, A. B. Annual variation in source contributions to a mixed stock: Implications for quantifying connectivity. Mol.Ecol. 17, 2185–2193, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03752.x (2008).

Arendt, M. D., Schwenter, J. A., Witherington, B. E., Meylan, A. B. & Saba, V. S. Historical versus contemporary climate forcing on the annual nesting variability of loggerhead sea turtles in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. PLoS ONE 8, e81097, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081097 (2013).

Van Houtan, K. S. & Halley, J. M. Long-term climate forcing in loggerhead sea turtle nesting. PLoS ONE 6, e19043, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019043 (2011).

Ascani, F., Van Houtan, K., Lorenzo, E. D., Polovina, J. J. & Jones, T. T. Juvenile recruitment in loggerhead sea turtles linked to decadal changes in ocean circulation. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 3529–3538, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13331 (2016).

Carr, A. F. Rips, FADs and little loggerheads. BioSci. 36, 92–100, https://doi.org/10.2307/1310109 (1986).

Bolten, A. B. et al. Transatlantic Developmental Migrations of Loggerhead Sea Turtles Demonstrated by mtDNA Sequence Analysis. Ecol. Appl. 8, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.2307/2641306 (1998).

Okuyama, T. & Bolker, B. M. Combining genetic and ecological data to estimate sea turtle origins. Ecol. Appl. 15, 315–325, https://doi.org/10.1890/03-5063 (2005).

Ehrhart, L. M., Redfoot, W., Bagley, D. & Mansfield, K. Long-Term Trends in Loggerhead (Caretta caretta) Nesting and Reproductive Success at an Important Western Atlantic Rookery. Chel. Conserv. Biol. 13, 173–181, https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-1100.1 (2014).

Bjorndal, K. A., Bolten, A. B., Dellinger, T., Delgado, C. & Martins, H. R. Compensatory Growth in Oceanic Loggerhead Sea Turtles: Response to a Stochastic Environment. Ecology 84, 1237–1249, https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1237:cgiols]2.0.co;2 (2003).

Bjorndal, K. A., Bolten, A. B. & Martins, H. R. Somatic growth model of juvenile loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta: duration of pelagic stage. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 202, 265–272, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps202265 (2000).

Avens, L. et al. Complementary skeletochronology and stable isotope analyses offer new insight into juvenile loggerhead sea turtle oceanic stage duration and growth dynamics. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 491, 235–251, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps10454 (2013).

Santos, M. A., Bolten, A. B., Martins, H. R., Riewald, B. & Bjorndal, K. A. Air-breathing visitors to seamounts: sea turtles. In Seamounts: Ecology Fisheries and Conservation (eds Pitcher, T. J., Morato, T., Hart, P. L. B., Clark, M. R., Haggan, A. & Santos, R.) 239–243, Blackwell publishing (2007).

Morato, T. et al. Abundance and distribution of seamounts in the Azores. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 357, 17–21, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps07268 (2008).

Machete, M. POPA-Fisheries Observer Program of the Azores: Turtle sightings in the Azores tuna fishery from 2000 on during navigation or search mode. Institute of Marine Research (IMAR), 10.14284/13 (2016).

Eguchi, T., Gerrodette, T., Pitman, R. L., Seminoff, J. A. & Dutton, P. H. At-sea density and abundance estimates of the olive ridley turtle Lepidochelys olivacea in the eastern tropical Pacific. Endang. Species Res. 3, 191–203, https://doi.org/10.3354/esr003191 (2007).

Witherington, B. E., Hirama, S. & Hardy, R. F. Young sea turtles of the pelagic Sargassum-dominated drift community: Habitat use, population density, and threats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 463, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09970 (2012).

Kie, J. G. A rule-based ad hoc method for selecting a bandwidth in kernel home-range analysis. Anim. Biotelem. 1–13; https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-3385-1-13 (2013).

Kobayashi, D. R. et al. Pelagic habitat characterization of loggerhead sea turtles, Caretta caretta, in the North Pacific Ocean (1997-2006): Insights from satellite tag tracking and remotely sensed data. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 356, 96–114, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2007.12.019 (2008).

Vasquez, M. et al. Broad-scale mapping of seafloor habitats in the north-east Atlantic using existing environmental data. J. Sea Res. 100, 120–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2014.09.011 (2015).

Buckland, S. T., Anderson, D. R., Burnham, K. P. & Laake, J. L. Distance Sampling: Methods and Applications. (Chapman and Hall, London, 1993).

Buckland, S. T. et al. Introduction to distance sampling: estimating abundance of biological populations. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001).

Buckland S. T. et al. Advanced Distance Sampling. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Second edition, Springer-Verlag, New York, https://doi.org/10.1007/b97636 (2002).

Miller, D. L., Rexstad, E., Thomas, L., Marshall, L. & Laake, J. L. Distance Sampling in R. J Stat. Software 89, 1–28, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v089.i01 (2019).

Marques, F. Estimating wildlife distribution and abundance from line transect surveys conducted from platforms of opportunity. PhD Thesis (2001).

Hedley, S. L. & Buckland, S. T. Spatial models for line transect sampling. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 9, 181–199, https://doi.org/10.1198/1085711043578 (2004).

Durant, S. M. et al. Long-term trends in carnivore abundance using distance sampling in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 1490–1500, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02042.x (2011).

Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R. Chapman and Hall/CRC (2006).

Wood, S. N., Pya, N. & Saefken, B. Smoothing parameter and model selection for general smooth models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 111, 1548–1575, https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2016.1180986 (2016).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/ (2018).

Canty, A. & Ripley, B. Boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions. R package version 1.3-20; https://cran.r-project.org/package=boot (2017).

Stoffer, D. astsa: Applied Statistical Time Series Analysis. R package version 1.8; http://cran.r-project.org/package=astsa (2014).

Bolten, A. B., Martins, H. R., Bjorndal, K. A. & Gordon, J. Size distribution of pelagic-stage loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in the waters around the Azores and Madeira. Arquipélago Life Mar. Sci. 2, 49–54 (1993).

Witherington, B. E., Kubis, P., Brost, B. & Meylan, A. Decreasing annual nest counts in a globally important loggerhead sea turtle population. Ecol. Appl. 19, 30–54, https://doi.org/10.1890/08-0434.1 (2009).

Santidrián Tomillo, P. et al. High beach temperatures increased female-biased primary sex ratios but reduced output of female hatchlings in the leatherback turtle. Biol. Conserv. 176, 71–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.05.011 (2014).

Wyneken, J. & Lolavar, A. Loggerhead sea turtle environmental sex determination: implications of moisture and temperature for climate change based predictions for species survival. J Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 324, 295–314, https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.b.22620 (2015).

Pike, D. A. Climate influences the global distribution of sea turtles nesting. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 22, 555–566, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12025 (2013).

Weishampel, J. F., Bagley, D. A. & Ehrhart, L. M. Earlier nesting by loggerhead sea turtles following sea surface warming. Glob. Chang. Biol. 10, 1424–1427, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0732-0 (2004).

Chaloupka, M. Y., Kamezaki, N. & Limpus, C. J. Is climate change affecting the population dynamics of the endangered Pacific loggerhead sea turtle? J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 356, 136–143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2007.12.009 (2008).

Putman, N. F., Bane, J. M. & Lohmann, K. J. Sea turtle nesting distributions and oceanographic constraints on hatchling migration. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 3631–3637, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.1088 (2010).

Bjorndal, K. A. et al. Temporal, spatial, and body size effects on growth rates of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in the Northwest Atlantic. Mar. Biol. 160, 2711–2721, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-013-2264-y (2013).

Bjorndal, K. A. et al. Somatic growth dynamics of West Atlantic hawksbill sea turtles: A spatio-temporal perspective. Ecosphere 7, e01279, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1279 (2016).

Bjorndal, K. A. et al. Ecological regime shift drives declining growth rates of sea turtles throughout the West Atlantic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 0, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1111/gbc.13712 (2017).

Milton, S. L., Leone-Kabler, S. L., Schulman, A. & Lutz, P. L. Effects of Hurricane Andrew on the Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches of South Florida. Bull. Mar. Sci. 54, 974–81 (1994).

Van Houtan, K. S. & Bass, O. L. Stormy oceans are associated with declines in sea turtle hatching. Curr. Biol. 17, 590–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.021 (2007).

Pike, D. A. & Stiner, J. C. Sea turtle species vary in their susceptibility to tropical cyclones. Oecologia 153, 471–478, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0732-0 (2007).

Brost, B. et al. Sea turtle hatchling production from Florida (USA) beaches, 2002–2012, with recommendations for analyzing hatching success. Endanger. Species Res. 27, 53–68, https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00653 (2015).

Lasker, R. Factors contributing to variable recruitment of the northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax) in the California Current: contrasting years, 1975 through 1978. Rapp. P-V Réun. Cons. Int. Explor. Mer 178, 375–388 (1981).

Fogarty, M. J., Sissenwine, M. P. & Cohen, E. B. Recruitment variability and the dynamics of exploited marine populations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 6, 241–246, https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(91)90069-a (1991).

Hare, S. R. & Mantua, N. J. Empirical evidence for North Pacific regime shifts in 1977 and 1989. Prog. Oceanogr. 47, 103–145, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6611(00)00033-1 (2000).

Weijerman, M., Lindeboom, H. & Zuur, A. F. Regime shifts in marine ecosystems of the North Sea and Wadden Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 298, 21–39, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps298021 (2005).

Ripley, B. J. & Caswell, H. Recruitment variability and stochastic population growth of the soft-shell clam, Mya arenaria. Ecol. Modell. 193, 517–530, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.07.033 (2006).

Perretti, C. T. et al. Regime shifts in fish recruitment on the Northeast US Continental Shelf. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 574, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12183 (2017).

Witherington, B. E. Ecology of neonate loggerhead turtles inhabiting lines of downwelling near a Gulf Stream front. Mar. Biol. 140, 843–853, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-001-0737-x (2002).

Mansfield, K. L., Wyneken, J., Porter, W. P. & Luo, J. First satellite tracks of neonate sea turtles redefine the ‘lost years’ oceanic niche. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20133039, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.3039 (2014).

Freitas, C., Caldeira, R. & Dellinger, T. Surface behaviour of pelagic juvenile loggerhead sea turtles in the eastern North Atlantic. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 510, 73–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2018.10.006 (2019).

Polovina, J. J., Kobayashi, D. R., Parker, D. M., Seki, M. P. & Balazs, G. H. Turtles on the edge: Movement of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) along oceanic fronts, spanning longline fishing grounds in the central North Pacific, 1997–1998. Fish. Oceanogr. 9, 71–82, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2419.2000.00123.x (2000).

Mansfield, K. L., Saba, V. S., Keinath, J. & Musick, J. A. Satellite telemetry reveals a dichotomy in migration strategies among juvenile loggerhead sea turtles in the northwest Atlantic. Mar. Biol. 156, 2555–2570, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-009-1279-x (2009).

Varo-Cruz, N. et al. New findings about the spatial and temporal use of the Eastern Atlantic Ocean by large juvenile loggerhead turtles. Divers. Distrib. 22, 71–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12413 (2016).

Chambault, P. et al. Swirling in the ocean: Immature loggerhead turtles seasonally target old anticyclonic eddies at the fringe of the North Atlantic gyre. Prog. in Oceanogr. 175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2019.05.005 (2019).

Morato, T., Hoyle, S. D., Allain, V. & Nicol, S. J. Seamounts are hotspots of pelagic biodiversity in the open ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9707–9711, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0910290107 (2010).

POPA - Programa de Observação para as Pescas dos Açores. Relatório de actividades, Horta (2010).

Osborn, T. J. Winter 2009/2010 temperatures and a record-breaking North Atlantic Oscillation index. Weather 66, 19–21, https://doi.org/10.1002/wea.666 (2011).

Taws, S. L., Marsh, R., Wells, N. C. & Hirschi, J. Re-emerging ocean temperature anomalies in late-2010 associated with a repeat negative NAO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL048978 (2011).

Buchan, J., Hirschi, J. J.-M., Blaker, A. T. & Sinha, B. North Atlantic SST Anomalies and the Cold North European Weather Events of Winter 2009/10 and December 2010. Mon. Weather Rev. 142, 922–932, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-13-00104.1 (2014).

Polovina, J. J. et al. Forage and migration habitat of loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) sea turtles in the central North Pacific Ocean. Fish Oceanogr. 13, 36–51, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2419.2003.00270.x (2004).

Hawkes, L. A., Broderick, A. C., Coyne, M. S., Godfrey, M. H. & Godley, B. J. Only some like it hot - quantifying the environmental niche of the loggerhead sea turtle. Diver. Distrib. 13, 447–457, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00354.x (2007).

Pirhalla, D. E., Sheridan, S. C., Ransibrahmanakul, V. & Lee, C. C. Assessing Cold-Snap and Mortality Events in South Florida Coastal Ecosystems: Development of a Biological Cold Stress Index Using Satellite SST and Weather Pattern Forcing. Est. Coast. 38, 2310–2322, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-014-9918-y (2014).

Smolowitz, R. J., Patel, S. H., Haas, H. L. & Miller, S. A. Using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to observe loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) behavior on foraging grounds off the mid-Atlantic United States. J.Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 471, 84–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2015.05.016 (2015).

Báez, J. C. The North Atlantic Oscillation and sea surface temperature affect loggerhead abundance around the Strait of Gibraltar. Sci. Mar. 75, 571–575, https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.2011.75n3571 (2011).

Alheit, J. Climate variability drives anchovies and sardines into the North and Baltic Seas. Prog. Oceanogr. 96, 128–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2011.11.015 (2012).

Barlow, J. Inferring trackline detection probabilities, g(0), for cetaceans from apparent densities in different survey conditions. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 31, 923–943, https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12205 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted within the framework of the projects COSTA, Consolidating Sea Turtle conservation in the Azores (US Fish and Wildlife Service, Marine Turtle Conservation Fund, n° F15AP00577, F16AP00626, F17AP00403, F18AP00321; Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research through funds from Disney Conservation Fund), and MISTIC’SEAS, Macaronesia Islands Standard Indicators and Criteria – Reaching Common Grounds on Monitoring Marine biodiversity in Macaronesia (EU DG-ENV/MSFD 11.0661/2015/712629/SUB/ENVC.2). We acknowledge the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) for the Post-doctoral grant (SFRH/BPD/110294/2015) attributed to FV and the funds provided through the strategic project (FCT/UID/MAR/04292/2013) granted to MARE. We would like to thank the former coordinator, R. Ferraz, and fishing observers of the Fisheries Observer Program of the Azores POPA, as well as the captains and crews of the Azorean tuna fleet. We would also like to thank Dr Helen Martins for her inspiration and contribution to sea turtle research in the Azores.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.V. and A.B.B. designed the study. M.M. and M.S. organised and coordinated the data acquisition. F.V. and H.P. conducted the statistical analysis. F.V., H.P., C.K.P., M.S., K.A.B. and A.B.B. interpreted the results. F.V. and H.P. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. F.V., H.P., C.K.P., K.A.B. and A.B.B. revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vandeperre, F., Parra, H., Pham, C.K. et al. Relative abundance of oceanic juvenile loggerhead sea turtles in relation to nest production at source rookeries: implications for recruitment dynamics. Sci Rep 9, 13019 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49434-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49434-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.