Abstract

Endemism is one of the most important concepts in biogeography and is of high relevance for conservation biology. Nevertheless, our understanding of patterns of endemism is still limited in many regions of high biodiversity. This is also the case for Iran, which is rich in biodiversity and endemism, but there is no up-to-date account of diversity and distribution of its endemic species. In this study, a comprehensive list of all endemic vascular plant species of Iran, their taxonomic composition and their geographical distribution are presented. To this end, a total of 2,597 (sub)endemic vascular plant species of Iran were documented and their distribution in three phytogeographical regions, two biodiversity hotspots and five areas of endemism were analysed. The Irano-Turanian phytogeographical region harbours 88% of the Iranian endemics, the majority of which are restricted to the Irano-Anatolian biodiversity hotspot (84%). Nearly three quarters of the endemic species are restricted to mountain ranges. The rate of endemism increases along an elevational gradient, causing the alpine zone to harbour a disproportionally high number of endemics. With increasing pastoralism, urbanization, road construction and ongoing climate change, the risk of biodiversity loss in the Iranian mountains is very high, and these habitats need to be more effectively protected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of endemism, which describes that a taxon is restricted in its distribution to a distinct area, is central in biogeography1. It is also considered a significant criterion for biodiversity conservation at the global, national and local scales2,3,4. Biodiversity is unevenly distributed both around the Earth and among the different lineages of the tree of life5,6. Areas with high concentration of narrowly distributed species are of high priority to preserve biodiversity3,7, and identification of areas with high priority for conservation is a fundamental task of conservation biogeography8,9. The number of endemic species in a biogeographic region is a first step for assessing the conservation situation of that region10. Documenting endemic richness in a biodiversity hotspot or area of endemism is important not only for setting their conservation priorities11, but also for understanding the evolutionary and ecological processes that have shaped the biodiversity hotspots in general and areas of endemism in particular12,13.

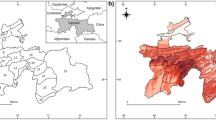

This study focuses on Iran, a vast country in Southwest Asia (Fig. 1a) with very diverse landscapes14,15,16 comprising a large number of arid to semi-arid mountain ranges. It is home to a high plant and animal diversity with more than 8,000 vascular plant taxa, approximately 30% of which are endemics17, and more than 1,000 species of mainland vertebrates14. Moreover, Iran is at the crossroads of three major phytogeographic regions (the Irano-Turanian, the Saharo-Sindian and the Euro-Siberian regions sensu White and Léonard18), covers parts of two global biodiversity hotspots, i.e. Irano-Anatolian and Caucasus7, and harbours five areas of endemism19. These areas of endemism are clearly associated with the major mountain ranges of the Iranian Plateau, harbouring the majority of the Iranian endemic flora19. The Iranian Plateau is one of the hotspots of evolutionary and biological diversity of the Old World and serves as a bridge for migration of many plants, connecting the eastern and western floras of Eurasia20. Despite its outstanding species richness, geographic extent, and evolutionary importance, and although it has been the object of several studies on endemism, diversity and chorology of plants17,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, there is no updated and comprehensive work available summarizing the diversity and distribution of endemic vascular flora in Iran as a whole, in its phytogeographical regions, in biodiversity hotspots and also in areas of endemism.

Global biodiversity hotspots, phytogeographic regions and areas of endemism in Iran. (a) Topographic map of Iran and adjacent regions showing the Irano-Anatolian and the Caucasus biodiversity hotspots. (b) Topographic map of Iran indicating phytogeographical regions (Irano-Turanian region indicated as yellow shaded area, the Saharo-Sindian region and the Euro-Siberian region indicated as unshaded areas south and north, respectively, of the Irano-Turanian region) and areas of endemism, well associated with high mountain ranges of Iran (indicated by outlines and their names).

In this study, we provide a complete and updated list of all endemic vascular plant species of Iran with their geographical distributions. Documenting all vascular plant species endemic to Iran, we can (1) uncover the taxonomic composition of the Iranian endemic flora, (2) estimate the number of Iranian endemics per phytogeographic region, biodiversity hotspot and area of endemism, (3) assess the floristic connections between areas of endemism, (4) quantify the contribution of large taxonomic groups to each area of endemism, (5) record the elevational distribution of endemic species, and finally (6) construct life form spectra in the biogeographical regions of Iran.

Results and Discussion

Taxonomic distribution of endemic diversity

The Iranian vascular flora includes a total of 2,597 endemic or subendemic species (32% of all native species), belonging to 359 genera within 65 families. There are no endemic families, but 26 endemic and subendemic genera (Table 1). Of those (sub)endemic genera, 19 are monotypic, two are ditypic and the remaining five multitypic. The highest number of (sub-)endemic genera is found in Apiaceae and Brassicaceae with 13 and 7 genera, respectively. However, data on endemic genera need to be viewed with caution because of uncertainty in taxonomic circumscription, for example generic re-alignments in Brassicaceae33,34,35,36 or addition of species to Parrotia37. Dicots contain 2,421 endemic species in Iran (93% of all vascular plant endemics) out of 6,889 species, monocots contain 175 endemics (7% of all vascular plant endemics) out of 1,164 species, and gymnosperms have only one endemic out of 10 species. None of the 53 pteridophyte species occurring in Iran is endemic. The percentage of endemism in dicots (35%) is much higher than in monocots (15%) and gymnosperms (10%). This likely is due to the high number of endemic species in a few eudicot genera, such as Astragalus (Fabaceae) and Cousinia (Astercaeae). The 10 largest families in terms of number of endemic species comprise 82% of the total Iranian endemic vascular flora (Fig. 2). Fabaceae is the number one in terms of endemic species (687 endemic species), which is due to the hyperdiverse genus Astragalus with ca. 800 species (70% endemics; Fig. 3), thus covering ca. 21% of the Iranian endemic vascular flora. The second largest family in terms of endemics is Asteraceae (Fig. 2), comprising 618 endemic species (48% of Asteraceae species). Cousinia is by far the largest genus of this family in Iran with 294 species (81% endemics; Fig. 3), encompassing 9% of the Iranian endemic species. Further families with high numbers of endemics are Lamiaceae (155), Apiaceae (127), Caryophyllaceae (127), Scrophulariaceae (96), Brassicaceae (88), Alliaceae (84), Boraginaceae (70), Rosaceae (69), and Plumbaginaceae (65; Fig. 2). Whereas these are all large families with respect to number of species present in Iran, Poaceae, which is the third biggest family in terms of total number of species (comprising 519 species) has only 28 endemic species (5%; Fig. 2). Although these numbers may decrease due to taxonomic revision27,38, new endemic species continue to be described17, rendering it unlikely that the overall pattern will change in the future.

The number of endemic species and the degree of endemism in the Iranian vascular flora is similar to Turkey, but twice that of Greece and the Iberian Peninsula (Table 2). Considering the smaller size of Turkey (about half of Iran), Turkey is proportionally richer than Iran. Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, Caryophyllaceae and Brassicaceae are among the ten richest families in the Mediterranean countries and in Iran, but differ in their order (Table 3). In all five Mediterranean regions, Asteraceae contains the highest number of endemic species (Table 3), as is typical for non-tropical regions39, but in Iran the high diversity of Astragalus renders Fabaceae the most endemic-rich family.

The ten richest genera in terms of endemic species account for 47% of the total number of endemics of Iran (Fig. 3). The largest genera of the vascular flora usually also comprise the largest number of endemic species (e.g., Astragalus, Cousinia, Allium). Exceptions are smaller genera with high proportion of endemics, such as Dionysia (Primulaceae) with 39 species and about 90% endemism (Fig. 3), and species-rich genera with few endemics, such as Carex, Trifolium, and Vicia, whose species tend to be widespread rendering those genera species-rich but endemic-poor also in other Mediterranean areas such as the Iberian Peninsula40.

Richness across the territories

The majority of the endemic vascular plant species of Iran (88%) are restricted to the Irano-Turanian region, whereas only 5% and 4% are restricted to the Saharo-Sindian and the Euro-Siberian regions, respectively; 3% is shared between the regions (Table 4). The Irano-Turanian region is richer than the two others, which is due to the size of this region as well as its topography, as it contains numerous mountain ranges, which generally are rich in endemics41,42. Some of the species-rich genera more strongly represented in this region are Astragalus (Fabaceae), Cousinia (Asteraceae), Acantholimon (Plumbaginaceae) and Allium (Alliaceae; Fig. 4a). A typical representative of the Euro-Siberian region is Alchemilla (Rosaceae), with nearly 90% of its endemics being found in this region. Akhani, et al.43 suggests for the Hyrcanian forests (within the Euro-Siberian region) a number of ca. 280 endemic and subendemic species, which is almost three times more than we found (Table 4). As they do not provide any species list, we cannot assess the source for this discrepancy, but contributing factors may include the geographic coverage of the study by Akhani, et al.43 also including areas outside of Iran (southeastern Azerbaijan) or taxonomic differences, but still the discrepancy is remarkable. In the Saharo-Sindian region, the proportion of Echinops (Asteraceae) species is high compared to other regions (Fig. 4a).

Patterns of endemism in global biodiversity hotspots present in Iran reflect those observed for biogeographic regions. Specifically, 84% of the Iranian vascular plant endemics are restricted to the Irano-Anatolian hotspot, which is inside the Irano-Turanian region, whereas only 4% of the Iranian vascular plant endemics are restricted to the Caucasian hotspot inside the Euro-Siberian region.

With respect to areas of endemism, Zagros is the richest, harbouring 45% of the Iranian vascular plant endemics, the majority of which is restricted to this region (Figs 5, 6 and Table 5). Zagros is a continuous mountain range connecting the Azerbaijan Plateau and Alborz in the north to the Yazd-Kerman massifs in the south (Fig. 1). However, the connectivity is more contiguous in the montane zone and diminishes and eventually ceases with increasing elevation (Fig. 1). This increased isolation coincides with increased endemism, resulting in high endemic richness in areas with high elevational range (Noroozi et al. 2018), and an overall uneven distribution of endemic richness across Zagros. All of the ten most endemic-rich genera of Iran except Oxytropis (Fabaceae) are well-represented in Zagros (Fig. 4b).

Endemic vascular plant species of Iran in areas of endemism. Endemic vascular plant species restricted to an area of endemism are indicated in dark grey, whereas those shared with other areas of endemism are indicated in light grey, their numbers being given in the bars connecting pie charts corresponding to areas of endemism.

The second-richest area is Alborz, which harbours 29% of all Iranian vascular plant endemics nearly half of them being restricted to Alborz (Figs 5, 6 and Table 5). If taking area size into account, Alborz is richer than other regions. This is particularly evident for range-restricted endemics (here species which are only in maximally three grid cells of 0.5° × 0.5°), where, compared to Zagros, Alborz has half the number of endemics on one fifth the area (Fig. 5; Table 5). Generally, Central Alborz has the highest concentration of endemics in the Iranian Plateau (Noroozi et al. 2018). Alborz is a narrow, but very high and contiguous east-west oriented mountain range (Fig. 1) that borders on lowland deserts in the south and on the Caspian Sea in the north. A wide elevational range, high topographic complexity and strong environmental heterogeneity explain its high plant diversity and great richness of endemics19. Alborz connects Kopet Dagh-Khorassan mountains in the east with the Azerbaijan Plateau and Zagros in the west (evident also in the high numbers of endemic species shared between Alborz and at least one of these regions; Fig. 6), thus acting as a corridor between Central Asia and Caucasus plus Anatolian mountains. Therefore, Alborz not only harbours a high number of local endemics, but also many elements showing biogeographic connections east- and/or westwards.

In the Azerbaijan Plateau, 21% of Iranian vascular plant endemics are found, half of which are endemic to this area (Figs 5, 6 and Table 5). The Azerbaijan Plateau has a fragmented orography caused by different tectonic and volcanic activities44. Although three times larger than Alborz, the Azerbaijan Plateau contains fewer endemics and range-restricted endemics (Fig. 5; Table 5). This area is close to the border of Iran and is connected to eastern Turkey and the Armenian mountains. Consequently, there are many species in this area shared with eastern Turkey, Transcaucasus and Caucasus22,45. Moreover, it is floristically linked to Alborz in the east and to Zagros in the south (Fig. 6). Nevertheless, it is diverse in local endemics, especially at higher elevations, which likely is due to the strong level of geographic isolation of single high summits (e.g., Sahand, Sabalan, Kiamaki). The Azerbaijan Plateau is the centre of diversification of Astragalus (Fabaceae; Fig. 4b)25,26.

The Kopet Dagh-Khorassan harbours 13% of Iranian vascular plant endemics, two thirds of which are restricted to this area (Figs 5, 6 and Table 5). Although of similar size to Alborz, Kopet Dagh-Khorassan harbours only about half as many endemics. This might be due to the lower topographic complexity and the smaller elevational range. Most of the endemic species of Kopet Dagh-Khorassan are range-restricted and rare. A high proportion of those endemics is from Cousinia (Asteraceae; Fig. 4b), which has its centre of diversification in these mountains38,46,47. Floristically, Kopet Dagh-Khorassan is most closely linked to Alborz among Iranian areas of endemism (Fig. 6).

The smallest proportion of vascular plant endemics is found in the Yazd-Kerman comprising 12% of Iranian vascular plant endemics, only one third of which is restricted to this area (Figs 5, 6 and Table 5). This area comprises several high elevation areas in southern Iran, topographically and thereupon floristically well connected to southern Zagros (Fig. 6). This spatial proximity to Zagros probably explains the relatively low proportion of endemics restricted to this region. At high elevations, the number of local endemics increases considerably, especially in Hezar and Lalezar Mts.48,49 and Shirkuh Mts. (Noroozi et al., unpublished data). A typical representative of the local endemic flora is Acantholimon (Plumbaginaceae; Fig. 4b), which is highly diverse in this area50,51. Additionally, the Yazd-Kerman harbours isolated occurrences of species otherwise distributed in Hindukush and Central Asian mountains, especially in alpine regions30,49,52,53.

Considerable differences can be observed among areas of endemism with respect to the richness of the 10 largest genera of the Iranian endemic vascular flora (Fig. 4b), as shall be illustrated with the following examples. Astragalus (Fabaceae), Allium (Alliaceae) and Centaurea (Asteraceae) are well represented in the Azerbaijan Plateau, but Acantholimon (Plumbaginaceae), Cousinia (Asteraceae) and Echinops (Asteraceae) are underrepresented in this area. Acantholimon, Echinops and Nepeta (Lamiaceae) are very well represented in Yazd-Kerman and Cousinia is very diverse in Kopet Dagh-Khorassan. Oxytropis (Fabaceae) is diverse in both Alborz and Kopet Dagh-Khorassan, but very poor in Zagros. The proportion of Silene (Caryophyllaceae) is high in Zagros, and Dionysia (Primulaceae) is a Zagros element with 29 endemic species in this mountain range, three species in Yazd-Kerman and only one species in Alborz.

Elevational distribution of endemics

The elevational distributions of surface area, non-endemic and endemic vascular plant species of Iran are displaced and peak at different elevations, as has already been found before on a taxonomically much smaller data set19. Despite a high proportion of surface area in lowlands (−26 to 1400 m), the proportions of non-endemics and especially of endemics in this elevation zone are low (Fig. 7). At mid elevations (1400 to 2800 m a.s.l.), the proportion of both non-endemics and endemics are high. At high elevations (2800 to 5671 m a.s.l.), although comprising only 1% of the surface area, the proportion of endemics becomes higher at the expense of the proportion of non-endemics. This confirms the importance of alpine habitats as endemism centres for vascular plants17.

Life forms

Hemicryptophytes are the most dominant life form (60%) among the endemic vascular plant species, followed by chamaephytes (26%), geophytes (6%), therophytes (5%) and phanerophytes (3%). There are considerable differences in the proportion of life forms in the three phytogeographical regions (Fig. 8a). Hemicryptophytes are dominant to almost equal extents in all three regions, whereas chamaephytes are very poor in the Euro-Siberian region. The Euro-Siberian region with its high precipitation and temperate climate is covered by Hyrcanian forests, resulting in an overrepresentation of phanerophytes and an underrepresentation of chamaephytes, geophytes and therophytes compared to the other two regions. The majority of chamaephytes of the Iranian vascular flora are thorn-cushions, a life form adapted to windswept slopes in the regions with Mediterranean precipitation regimes54; such chamaephytes are dominant in the mountains of the Irano-Turanian region54,55,56,57,58. Geophytes are underrepresented and therophytes are prominent in the Saharo-Sindian region.

In areas of endemism, the life form spectra are roughly similar among the areas (Fig. 8b). Exceptions are the Yazd-Kerman area with a high proportion of therophytes, Kopet Dagh-Khorassan with a low proportion of therophytes, and the Azerbaijan Plateau with a low proportion of phanerophytes compared to the other areas or to the average for Iran (Fig. 8b). The higher proportion of therophytes in Yazd-Kerman might be due to the longer warm and dry season on these mountains, which allows penetration by elements from the Saharo-Sindian region, whose flora is rich in therophytes.

Conclusion

Mountains influence the distribution and diversification of species and also maintain biodiversity over time59. Half of all the biodiversity hotspots are situated in mountains3, and our results indicate that 74% of all endemic vascular plant species of Iran are restricted to its mountains, which represent only about 42% of the country’s surface (elevations above 1400 m a.s.l.; Fig. 7). Generally, mountains with diverse micro-climates and topographic complexity promote high biodiversity and endemism60,61, which appears also to be the case for Iranian mountains19. The environmental heterogeneity provides diverse niche space allowing more species to coexist62, acts as trigger for diversification, resulting from isolation or adaptation to diverse environmental conditions63, and also enables the existence of particular habitats through longer time periods supporting relics64. The complex topography and the large elevational range potentially allowed Iranian plants to survive the Quaternary glaciations, as only the high elevations were covered with ice65 and lowlands could act as refugia for many relict elements such as Parrotia in the Hyrcanian Forests66. Additionally, Quaternary climatic fluctuations and associated shifts in habitats and vegetation zones may have triggered species diversification as, for instance, suggested for a group of steppe species within the hyperdiverse genus Astragalus67. However, understanding the origin of the biodiversity of the mountains of Iran requires molecular phylogenetic studies of their characteristic mega-genera. Until then, the evolutionary history of the taxa inhabiting these mountains remains one of the least understood fields of global biogeography, even though it is crucial for explaining the origin of plant diversity in mountains of Eurasia.

In Mediterranean mountain ranges, species richness has decreased during the past decade68. As the overall climate conditions in Iran are similar to those from Mediterranean regions, a decline of high-altitude habitats in the course of climate warming and reduced water availability can be expected in this region. Furthermore, pastoralism causes dramatic disturbance of mountain habitats of Iran. Pastoralism dates back to the Neolithic period69,70, since when it was extreme in several phases71. Pastoralism has already reduced the habitats of tree species like Quercus macranthera (Fagaceae) at the upper limit of the Hyrcanian forests and Juniperus excelsa (Cupressaceae) in the treeline zone of the southern slopes of Alborz72. Thus, with increasing anthropogenic pressure via pastoralism, urbanization, and road construction as well as ongoing global warming, mountain species are under increasing threat and need to be more strongly protected. According to the IUCN Red List, about one hundred species of the vertebrate fauna in Iran are considered vulnerable or already endangered73. For plants, nearly 60% of endemic vascular plant species of Iran are range-restricted and can be categorized as IUCN threatened species. Our knowledge about the centres of endemism in the Iranian Plateau is, however, still limited and future efforts will be needed to identify hotspots at a finer scale, “hotspots-within-hotspots”8,74,75, to aid practical conservation management.

Materials and Methods

Study area

Iran, with a surface area of c. 1.6 million km², is located between Central Asia and Himalaya in the east and Caucasus and Anatolia in the west. Iran displays considerable geologic and lithospheric heterogeneity, owing to its complex tectonic history76. One of the main tectonic events that influenced the geology and topography of Iran is the Arabia-Eurasia collision, which caused the uplift of numerous mountain ranges in the region, especially between the middle Miocene and the Pliocene77. The five major mountainous areas of Iran are the Azerbaijan Plateau, Alborz, Kopet Dagh-Khorassan, Zagros and the Yazd-Kerman massifs which are well associated with five areas of endemism (Fig. 1b). The elevation in Iran ranges from 26 m b.s.l. along the shore of the Caspian Sea up to 5,671 m a.s.l. at Damavand Mt. in Central Alborz. The climate is diverse and ranges from hot and dry deserts with precipitation of less than 25 mm/yr in central Iran to sub-tropical humid climates at the southern shore of the Caspian Sea with precipitation exceeding 1,800 mm/yr78. Nevertheless, major parts of Iran are characterised by continental climate with hot and dry summers, cold and harsh winters, and low precipitation66,79. Based on the Global Bioclimatic Classification System80,81 Iran is at the crossroad of three macrobioclimates (i.e. Mediterranean, tropical and temperate), correlating with the Irano-Turanian, Saharo-Sindian and Euro-Siberian biogeographical regions, respectively79,82.

Diverse climate and topography are paralleled by a multitude of vegetation types including desert and semidesert steppes, montane grasslands, wetlands, subalpine, alpine and subnival habitats, different types of shrublands and woodlands, deciduous temperate to subtropical forests, halophyte and even mangrove vegetation types66. These vegetation types are distributed in different elevational zones from 26 m b.s.l. up to 4,850 m a.s.l.72. Most of the biodiversity of Iran is centred within the two global biodiversity hotspots, i.e. the Irano-Anatolian and Caucasus hotspots (Fig. 1a), on five groups of mountain ranges (Fig. 1b). Iran covers 54% of the Irano-Anatolian hotspot and around 10% of the Caucasus hotspot (Fig. 1a). The species richness is not evenly distributed over the country and five areas of endemism have been identified, all of which are located in the Irano-Anatolian hotspot, and are well associated with major mountain ranges Fig. 1b;19. Azerbaijan Plateau, Alborz, Central Alborz, Zagros, the and Kopet Dagh-Khorassan were identified as areas of endemism in the Iranian Plateau based on data from Asteraceae19. Using the same approach (endemicity analysis) on the entire endemic vascular flora of Iran and a finer grid cell size, Yazd-Kerman is identified as an additional area of endemism (Noroozi et al., unpublished data), and is considered as such in this study. The Talysh mountains, which are located between Alborz and Azerbaijan, have a transitional situation, but their vascular flora is more linked to the Azerbaijan Plateau than to Alborz (Noroozi et al., unpublished data).

Species distribution data

All endemic and subendemic vascular plant species of Iran were documented. A species was considered endemic if its range is restricted to Iran, and considered subendemic if its main distribution (>80% of the known range or occurrences) lies within this country. We considered only taxa at the species level, but not subspecies or varieties. The documentation of species and the characterization of their geographical and altitudinal ranges were based on Flora Iranica83, Flora of Iran84 and monographs published after these floras until the end of 2016 (see Appendix S1, S2). The Flora Iranica taxonomic system is followed for family and genus level. The localities of all species were geo-referenced with a precision of at least 0.25° using Google Earth. Presence of species was then recorded on the basis of a grid with cell size of 0.5° × 0.5°. Species present in maximally three grid cells were considered as range-restricted endemics even if the grid cells were non-adjacent. We compared area size of Iran, number of total vascular plant species, number of vascular plant endemic species and the ten largest vascular plant families of Iran with those from other countries and regions in the west with similar climate, i.e. Mediterranean (Turkey, Greece, Italy, Morocco and Iberian Peninsula). The number of endemic vascular plant species of Iran and their restriction to the three phytogeographical regions18, two biodiversity hotspots7, and five areas of endemism19 (but not distinguishing Central Alborz, as it is geographically nested within Alborz, but additionally recognizing Yazd-Kerman) were analysed. Using the life form system of Raunkiaer85, the following five categories were used: chamaephytes, geophytes, hemicryptophytes, phanerophytes, and therophytes.

References

Anderson, S. Area and endemism. The Quarterly Review of Biology 69, 451–471 (1994).

Lamoreux, J. F. et al. Global tests of biodiversity concordance and the importance of endemism. Nature 440, 212–214, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04291 (2006).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858, https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501 (2000).

Riemann, H. & Ezcurra, E. Plant endemism and natural protected areas in the peninsula of Baja California, Mexico. Biological Conservation 122, 141–150, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2004.07.008 (2005).

Gotelli, N. J. et al. Patterns and causes of species richness: a general simulation model for macroecology. Ecology Letters 12, 873–886, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01353.x (2009).

Lévêque, C. & Mounolou, J.-C. Biodiversity (Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2007).

Mittermeier, R. A. et al. Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions (Conservation International, 2005).

Cañadas, E. M. et al. Hotspots within hotspots: Endemic plant richness, environmental drivers, and implications for conservation. Biological Conservation 170, 282–291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.12.007 (2014).

Morrone, J. J. The spectre of biogeographical regionalization. Journal of Biogeography 45, 282–288, https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13135 (2018).

Treurnicht, M., Colville, J. F., Joppa, L. N., Huyser, O. & Manning, J. Counting complete? Finalising the plant inventory of a global biodiversity hotspot. PeerJ 5, e2984, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2984 (2017).

Marshall, C. A. M., Wieringa, J. J. & Hawthorne, W. D. Bioquality hotspots in the tropical African flora. Current Biology 26, 3214–3219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.045 (2016).

Harold, A. S. & Mooi, R. D. Areas of endemism: definition and recognition criteria. Systematic Biology 43, 261–266, https://doi.org/10.2307/2413466 (1994).

Morrone, J. J. Evolutionary Biogeography: An Integrative Approach with Case Studies (Columbia University Press, 2008).

Firouz, E. The Complete Fauna of Iran (Tauris, I. B., 2005).

Frey, W., Kürschner, H. & Probst, W. In Encyclopaedia Iranica (ed Yarshater, E.) 43–63 (Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa, 1999).

Zohary, M. In Plant Life of South-West Asia (eds Davis, P. H., Harper. P. C., & Hedge, I. C.) 43–52 (Botanical Society of Edinburgh, 1971).

Noroozi, J., Moser, D. & Essl, F. Diversity, distribution, ecology and description rates of alpine endemic plant species from Iranian mountains. Alpine Botany 126, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00035-015-0160-4 (2016).

White, F. & Léonard, J. Phytogeographical links between Africa and Southwest Asia. Flora et Vegetatio Mundi 9, 229–246 (1991).

Noroozi, J. et al. Hotspots within a global biodiversity hotspot - areas of endemism are associated with high mountain ranges. Scientific Reports 8, 10345, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28504-9 (2018).

Manafzadeh, S., Salvo, G. & Conti, E. A tale of migrations from east to west: the Irano-Turanian floristic region as a source of Mediterranean xerophytes. Journal of Biogeography 41, 366–379, https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12185 (2014).

Akhani, H. A new spiny, cushion-like Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) from south-west Iran with special reference to the phytogeographic importance of local endemic species. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 146, 107–121, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2004.00310.x (2004).

Akhani, H. Diversity, biogeography, and photosynthetic pathways of Argusia and Heliotropium (Boraginaceae) in South-West Asia with an analysis of phytogeographical units. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 155, 401–425, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2007.00707.x (2007).

Freitag, H. Notes on the distribution, climate and flora of the sand deserts of Iran and Afghanistan. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Section B: Biological Sciences 89, 135–146, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269727000008976 (1986).

Hedge, I. C. & Wendelbo, P. Patterns of distribution and endemism in Iran. Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh 36, 441–464 (1978).

Mahmoodi, M., Maassoumi, A. A. & Hamzeh’ee, B. Geographical distribution of Astragalus (Fabaceae) in Iran. Rostaniha 10, 112–132 (2009).

Mahmoodi, M., Maassoumi, A. A. & Jalili, A. Distribution patterns of Astragalus in the Old World based on some selected sections. Rostaniha 13, 39–56 (2012).

Memariani, F., Akhani, H. & Joharchi, M. R. Endemic plants of Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province in Irano-Turanian region: diversity, distribution patterns and conservation status. Phytotaxa 249, 31–117, https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.249.1.5 (2016).

Memariani, F., Zarrinpour, V. & Akhani, H. A review of plant diversity, vegetation, and phytogeography of the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province in the Irano-Turanian region (northeastern Iran–southern Turkmenistan). Phytotaxa 249, 8–30, https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.249.1.4 (2016).

Noroozi, J., Akhani, H. & Breckle, S.-W. Biodiversity and phytogeography of the alpine flora of Iran. Biodiversity and Conservation 17, 493–521, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-007-9246-7 (2008).

Noroozi, J., Pauli, H., Grabherr, G. & Breckle, S.-W. The subnival–nival vascular plant species of Iran: a unique high-mountain flora and its threat from climate warming. Biodiversity and Conservation 20, 1319–1338, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-011-0029-9 (2011).

Sales, F. & Hedge, I. C. Generic endemism in South-West Asia: an overview. Rostaniha 14, 22–35 (2013).

Wendelbo, P. In Plant Life of South-West Asia (eds Davis, P. H., Harper, P. C., & Hedge, I. C.) 29–41 (Botanical Society of Edinburgh., 1971).

Al-Shehbaz, I. A. A generic and tribal synopsis of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae). Taxon 61, 931–954 (2012).

Hedge, I. C. In The Biology and Chemistry of the Cruciferae (eds J.G. Vaughan, A. J. Mac Leod, & B. M. G. Jones) 1–45 (Academic Press, 1976).

Moazzeni, H., Zarre, S., Al-Shehbaz, I. A. & Mummenhoff, K. Seed-coat microsculpturing and its systematic application in Isatis (Brassicaceae) and allied genera in Iran. Flora 202, 447–454, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2006.10.004 (2007).

Mummenhoff, K., Al-Shehbaz, I. A., Bakker, F. T., Linder, H. P. & Mühlhausen, A. Phylogeny, morphological evolution, and speciation of endemic Brassicaceae genera in the Cape flora of southern Africa. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 92, 400–424 (2005).

Li, J. & Del Tredici, P. The Chinese Parrotia: a sibling species of the Persian Parrotia. Arnoldia 66, 2–9 (2008).

Mehregan, I. & Kadereit, J. W. Taxonomic revision of Cousinia sect. Cynaroideae (Asteraceae, Cardueae). Willdenowia 38, 293–362, https://doi.org/10.3372/wi.38.38201 (2008).

Hobohm, C. Endemism in Vascular Plants. (Springer, 2014).

Buira, A., Aedo, C. & Medina, L. Spatial patterns of the Iberian and Balearic endemic vascular flora. Biodiversity and Conservation 26, 479–508, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1254-z (2017).

Hobohm, C. & Tucker, C. M. In Endemism in Vascular Plants (ed Carsten Hobohm) 3–9 (Springer, 2014).

Spehn, E. M., Rudmann-Maurer, K. & Körner, C. Mountain biodiversity. Plant Ecology & Diversity 4, 301–302, https://doi.org/10.1080/17550874.2012.698660 (2011).

Akhani, H., Djamali, M., Ghorbanalizadeh, A. & Ramezani, E. Plant biodiversity of Hyrcanian relict forests, N Iran: An overview of the flora, vegetation, palaeoecology and conservation. Pakistan Journal of Botany 42, 231–258 (2010).

Innocenti, F., Manetti, P., Mazzuoli, R., Pasquaré, G. & Villari, L. In Andesites: Orogenic Andesites and Related Rocks (ed. Thorpe, R. S.) 327–349 (John Wiley & Sons, 1982).

Noroozi, J., Willner, W., Pauli, H. & Grabherr, G. Phytosociology and ecology of the high-alpine to subnival scree vegetation of N and NW Iran (Alborz and Azerbaijan Mts.). Applied Vegetation Science 17, 142–161, https://doi.org/10.1111/avsc.12031 (2014).

Knapp, H. D. On the distribution of the genus Cousinia (Compositae). Plant Systematics and Evolution 155, 15–25, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00936283 (1987).

López-Vinyallonga, S., Mehregan, I., Garcia-Jacas, N. & Kadereit, J. W. Phylogeny and evolution of the Arctium-Cousinia complex (Compositae,Cardueae-Carduinae). Taxon 58, 153–171, https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.581016 (2009).

Noroozi, J., Ajani, Y. & Nordenstam, B. A new annual species of Senecio (Compositae-Senecioneae) from subnival zone of southern Iran with comments on phytogeographical aspects of the area. Compositae Newsletter 48, 43–62 (2010).

Rajaei, P., Maassoumi, A. A., Mozaffarian, V., Nejad Sattari, T. & Pourmirzaei, A. Alpine flora of Hezar mountain (SE Iran). Rostaniha 12, 111–127 (2011).

Assadi, M. Distribution patterns of the genus Acantholimon (Plumbaginaceae) in Iran. Iranian Journal of Botany 12, 114–120 (2006).

Moharrek, F., Kazempour-Osaloo, S., Assadi, M. & Feliner, G. N. Molecular phylogenetic evidence for a wide circumscription of a characteristic Irano-Turanian element: Acantholimon (Plumbaginaceae: Limonioideae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 184, 366–386, https://doi.org/10.1093/botlinnean/box033 (2017).

Ajani, Y., Noroozi, J. & Levichev, I. G. Gagea alexii (Liliaceae), a new record from subnival zone of southern Iran with key and notes on sect. Incrustatae. Pakistan Journal of Botany 42, 67–77 (2010).

Doostmohammadi, M. & Kilian, N. Lactuca pumila (Asteraceae, Cichorieae) revisited—additional evidence for a phytogeographical link between SE Zagros and Hindu Kush. Phytotaxa 307, 133–140, https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.307.2.4 (2017).

Kürschner, H. The subalpine thorn-cushion formations of western South-West Asia: ecology, structure and zonation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B. Biological Sciences 89, 169–179, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269727000009003 (1986).

Klein, J. C. Les pelouses xérophiles d’altitude du flanc sud de l’Alborz central (Iran). Phytocoenologia 15, 253–280 (1987).

Klein, J. C. Les groupements à grandes ombellifères et à xérophytes orophiles: Essai de synthèse à l’échelle de la région irano-touranienne. Phytocoenologia 16, 1–36 (1988).

Noroozi, J., Akhani, H. & Wıllner, W. Phytosociological and ecological study of the high alpine vegetation of Tuchal Mountains (Central Alborz, Iran). Phytocoenologia 40, 293–321, https://doi.org/10.1127/0340-269X/2010/0040-0478 (2010).

Noroozi, J., Hülber, K. & Willner, W. Phytosociological and ecological description of the high alpine vegetation of NW Iran. Phytocoenologia 47, 233–259, https://doi.org/10.1127/phyto/2017/0108 (2017).

Hoorn, C., Perrigo, A. & Antonelli, A. Mountains, Climate and Biodiversity (Wiley-Blackwell, 2018).

Irl, S. D. H. et al. Climate vs. topography – spatial patterns of plant species diversity and endemism on a high-elevation island. Journal of Ecology 103, 1621–1633, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12463 (2015).

Steinbauer, M. J. et al. Topography-driven isolation, speciation and a global increase of endemism with elevation (Forthcoming). Global Ecology and Biogeography 25, 1097–1107, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12469 (2016).

Tews, J. et al. Animal species diversity driven by habitat heterogeneity/diversity: the importance of keystone structures. Journal of Biogeography 31, 79–92, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0305-0270.2003.00994.x (2004).

Hughes, C. & Eastwood, R. Island radiation on a continental scale: Exceptional rates of plant diversification after uplift of the Andes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 10334–10339, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601928103 (2006).

Fjeldså, J., Bowie, R. C. K. & Rahbek, C. The role of mountain ranges in the diversification of birds. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 43, 249–265, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145113 (2012).

Becker, D., Verheul, J., Zickel, M. & Willmes, C. LGM paleoenvironment of Europe - Map. CRC806-Database, https://doi.org/10.5880/SFB806.15 (2015).

Zohary, M. Geobotanical Foundations of the Middle East 2. (Gustav Fischer, 1973).

Bagheri, A., Maassoumi, A. A., Rahiminejad, M. R., Brassac, J. & Blattner, F. R. Molecular phylogeny and divergence times of Astragalus section Hymenostegis: An analysis of a rapidly diversifying species group in Fabaceae. Scientific Reports 7, 14033, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14614-3 (2017).

Pauli, H. et al. Recent plant diversity changes on Europe’s mountain summits. Science 336, 353–355, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1219033 (2012).

Diamond, J. Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature 418, 700–707, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01019 (2002).

Zeder, M. A. & Hesse, B. The initial domestication of goats (Capra hircus) in the Zagros Mountains 10,000 years ago. Science 287, 2254–2257, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.287.5461.2254 (2000).

Djamali, M. et al. A late Holocene pollen record from Lake Almalou in NW Iran: evidence for changing land-use in relation to some historical events during the last 3700 years. Journal of Archaeological Science 36, 1364–1375, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.01.022 (2009).

Noroozi, J. & Körner, C. A bioclimatic characterization of high elevation habitats in the Alborz mountains of Iran. Alpine Botany 128, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00035-018-0202-9 (2018).

Jowkar, H., Ostrowski, S., Tahbaz, M. & Zahler, P. The conservation of biodiversity in Iran: threats, challenges and hopes. Iranian Studies 49, 1065–1077, https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2016.1241602 (2016).

Harris, G. M., Jenkins, C. N. & Pimm, S. L. Refining biodiversity conservation priorities. Conservation Biology 19, 1957–1968, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00307.x (2005).

Murray-Smith, C. et al. Plant diversity hotspots in the Atlantic coastal forests of Brazil. Conservation Biology 23, 151–163, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01075.x (2009).

Stöcklin, J. Structural history and tectonics of Iran; a review. AAPG Bulletin 52, 1229–1258 (1968).

Berberian, M. & King, G. C. P. Towards a paleogeography and tectonic evolution of Iran. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 18, 210–265, https://doi.org/10.1139/e81-019 (1981).

Djamali, M. Palaeoenvironmental Changes in Iran During the Last Two Climatic Cycles (Vegetation-Climate-Anthropisation). Unpublished PhD thesis. (Aix-Marseille, 2008).

Djamali, M., Brewer, S., Breckle, S. W. & Jackson, S. T. Climatic determinism in phytogeographic regionalization: A test from the Irano-Turanian region, SW and Central. Asia. Flora 207, 237–249, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2012.01.009 (2012).

Rivas-Martínez, S. Syntaxonomical synopsis of the potential natural plant communities of North America, I:(Compedio sintaxonómico de la vegetación natural potencial de Norteamérica, I). Itinera Geobotanica 10, 5–148 (1997).

Rivas-Martínez, S., Sánchez-Mata, D. & Costa, M. Boreal and western Temperate forest vegetation (syntaxonomical synopsis of the potential natural plant communities of North America II). Itinera Geobotanica 12, 3–311 (1999).

Djamali, M. et al. Application of the Global Bioclimatic Classification to Iran: implications for understanding the modern vegetation and biogeography. Ecologia Mediterranea 37, 91–114 (2011).

Rechinger, K. H. Flora Iranica. Vol. 1–181 (Akad. Druck- Verlagsanstalt. & Naturhist. Mus. Wien, 1963–2015).

Assadi, M., Khatamsaz, M., Maassoumi, A. A. & Mozaffarian, V. Flora of Iran. (Research Institute of Forests & Rangelands, 1989–2018).

Raunkiaer, C. The Life Forms of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography. (Clarendon Press, 1934).

Acknowledgements

We thank the numerous colleagues for contributing to the data set of the flora of Iran. Financial support by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, P28489-B29 to G.M.S.) is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.N. conceived the ideas; J.N., A.T., M.D. and Z.A. collected the data; J.N. analyzed the data, and led the writing with all co-authors contributing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noroozi, J., Talebi, A., Doostmohammadi, M. et al. Endemic diversity and distribution of the Iranian vascular flora across phytogeographical regions, biodiversity hotspots and areas of endemism. Sci Rep 9, 12991 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49417-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49417-1

This article is cited by

-

The amount of antioxidants in honey has a strong relationship with the plants selected by honey bees

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Consequence of habitat specificity: a rising risk of habitat loss for endemic and sub-endemic woody species under climate change in the Hyrcanian ecoregion

Regional Environmental Change (2024)

-

Climate change impacts on optimal habitat of Stachys inflata medicinal plant in central Iran

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Alien flora of Iran: species status, introduction dynamics, habitats and pathways

Biological Invasions (2023)

-

Habitat characteristics, ecology and biodiversity drivers of plant communities associated with Cousinia edmondsonii, an endemic and critically endangered species in NE Iran

Community Ecology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.