Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a heterogenic, functional gastrointestinal disorder of the gut-brain axis characterized by altered bowel habit and abdominal pain. Preclinical and clinical results suggested that, in part of these patients, pain may result from fungal induced release of mast cell derived histamine, subsequent activation of sensory afferent expressed histamine-1 receptors and related sensitization of the nociceptive transient reporter potential channel V1 (TRPV1)-ion channel. TRPV1 gating properties are regulated in lipid rafts. Miltefosine, an approved drug for the treatment of visceral Leishmaniasis, has fungicidal effects and is a known lipid raft modulator. We anticipated that miltefosine may act on different mechanistic levels of fungal-induced abdominal pain and may be repurposed to IBS. In the IBS-like rat model of maternal separation we assessed the visceromotor response to colonic distension as indirect readout for abdominal pain. Miltefosine reversed post-stress hypersensitivity to distension (i.e. visceral hypersensitivity) and this was associated with differences in the fungal microbiome (i.e. mycobiome). In vitro investigations confirmed fungicidal effects of miltefosine. In addition, miltefosine reduced the effect of TRPV1 activation in TRPV1-transfected cells and prevented TRPV1-dependent visceral hypersensitivity induced by intracolonic-capsaicin in rat. Miltefosine may be an attractive drug to treat abdominal pain in IBS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abdominal pain is the key contributing factor to severity of IBS and, mainly due to the lack of pathophysiological insight, a major unmet clinical need1,2. Visceral hypersensitivity, diagnosed as a decreased threshold of discomfort to colorectal distension, is observed in ~50% of patients and thought to be an underlying mechanism for abdominal pain3. We recently showed intestinal mycobiome dysbiosis in hypersensitive IBS patients and addressed the possible importance of this finding in the rat maternal separation model for IBS-like visceral hypersensitivity4. Not only did we observe profound mycobiome dysbiosis in maternal separated rats but also provided evidence for the functional relevance of dysbiosis by conducting fecal transfer experiments in fungicide treated animals. In addition, post stress hypersensitivity to colorectal distension was reversed by blocking host recognition of particulate β-glucans. Innate immune cells recognize these fungal cell wall components via the C-type lectin receptor dectin-1 that signals via spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk). The in vivo use of soluble β-glucans that antagonize dectin-1 activation and a Syk inhibitor independently inhibited the pain response. Subsequent ex vivo experiments then indicated that particulate β-glucans trigger mast cell degranulation. Earlier studies in the maternal separation model already showed that mast cell degranulation and subsequent histamine receptor-1 activation are key events in post stress visceral hypersensitivity5,6. A role for mast cells in IBS was confirmed some years ago7,8,9. More recently, Wouters et al. used the histamine receptor-1 antagonist ebastine to reduce visceral hypersensitivity and abdominal pain in IBS patients10. In the same investigation, live calcium imaging experiments with patient rectal biopsies suggested that the underlying mechanism involves histamine receptor-1 mediated sensitization of TRPV1. Indeed, an important role for this nociceptive ligand-gated cation channel was already predicted in the maternal separation model, where post stress visceral hypersensitivity was reversed by a specific TRPV1 antagonist6.

Taken together, the above data suggest that post stress visceral hypersensitivity results from immune recognition of an aberrant mycobiome via the dectin-1/Syk pathway, leading to mast cell degranulation and subsequent activation of histamine-1 receptors on sensory neurons, which in turn leads to sensitization of TRPV1 and pain signaling. The process of drug development for newly identified targets such as the ones described here is costly and time-consuming. Repurposing of existing drugs with established side effects may partly circumvent these issues11. In search for candidate drugs to treat abdominal pain complaints in IBS, we evaluated the FDA approved compound miltefosine. This alkyl-phospholipid was, largely unsuccessful, developed as an antitumor drug but is now approved as an oral treatment of visceral leishmaniasis12,13. Miltefosine however, was also shown to have broad-spectrum in vitro and in vivo fungicidal activity by triggering metacaspase (MCA1)-dependent apoptosis in fungal target cells14,15. Thus, in vivo administration of this compound may lead to favorable mycobiome modulation in dysbiotic subjects. Miltefosine also inhibited in vitro mast cell activation, and oral and topical administration were successfully evaluated in mast cell driven skin conditions16,17,18,19. Mast cells are modulated in the cytosol by inhibition of Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C (cPKC)18 and, due to insertion of this phosphatidylcholine analogue, at the plasma membrane were it behaves as a lipid raft modulator13,20. Lipid rafts are specialized membrane microdomains that are formed by tightly packed aggregates of phospholipids, glycolipids and cholesterol together with protein receptors, which can be included or excluded depending on their affinity. These rafts act as signal transduction moieties21. In trigeminal sensory neurons and TRPV1 transfected cell lines, disruption of raft integrity affected TRPV1 receptor activation by inhibiting opening properties of the cation channel22. Although raft disrupting strategies other than miltefosine were used, these result suggest that miltefosine, in addition to direct targeting of the mycobiome and mast cells, may also interfere with TRPV1 receptor activation to alleviate abdominal pain in IBS.

Here, we evaluated the effect of miltefosine treatment in two different models of visceral hypersensitivity. In the rat maternal separation model, we addressed the possible correlation between miltefosine-induced reversal of post-stress visceral hypersensitivity and fecal myco- and microbiome alterations. Reported fungicidal and bactericidal effects of miltefosine15,23 were confirmed with in vitro agar disk diffusion tests. Finally, we evaluated whether miltefosine reduces the effect of TRPV1 activation in TRPV1-transfected cells, and investigated its effect on in vivo TRPV1-dependent visceral hypersensitivity in a rat model of intracolonic capsaicin.

Results

Miltefosine treatment reverses post-stress visceral hypersensitivity in maternal separated rats

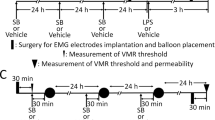

To address the possible therapeutic potential of miltefosine, we first evaluated its effects in the rat maternal separation model (experimental setup depicted in Fig. 1A). Similar to our previous investigations4,5,6,24,25, WA-stress at adult age did not lead to enhanced visceromotor response to colorectal distension in nonhandled rats (Fig. 1B, day 0 vs day 1). Moreover, 7 days post-WA treatment with vehicle or miltefosine (10 mg/kg/day) did not change the visceral sensitivity status of these nonhandled animals (day 1 vs day 8). Compared to pre WA, all 4 maternal separation groups showed enhanced visceromotor response to distension after WA-stress (Fig. 1C, day 0 vs day 1). This response was reversed after 7 day treatment with 1 mg miltefosine/kg (day 1 vs day 8), but not by vehicle, 0.1 and 10 mg miltefosine/kg. Lack of significant reversal in the 10 mg/kg treatment group may be due to relatively low post-stress visceral sensitivity at day 1. The latter is illustrated by comparing the mean difference in area under the curve (AUC in arbitrary units) between day 0 and day 1 (i.e. pre- vs post-WA) of the 1 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg treatment groups; Δ AUC 42 and 20 respectively.

Miltefosine treatment reversed post water avoidance (WA) visceral hypersensitivity in maternally separated rats. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental set-up; the visceromotor response (VMR) to distension was measured before and 24 hours after WA, and after 7 day miltefosine or vehicle treatment. Data shown in histograms (B,C) reflect results of nonhandled and maternal separated rats respectively. Data are given as area under the curve of the relative response to colorectal distension. All data are mean +/− SD, n = 7–10, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Repeated Measures one-way ANOVA, Sidak’s post hoc test).

Miltefosine inhibits in vitro growth of Candida albicans and Bacillus subtilis

Fungicidal and bactericidal activity may be relevant to the observed miltefosine-induced reversal of post-stress visceral hypersensitivity in maternal separated rats. Therefore, we carried out radial diffusion assays to confirm antibiotic activity. In C. albicans seeded agar, the inhibitory effect of nystatin justified the use of this assay as an anti-fungal readout (Fig. 2A). Compared to vehicle (i.e. phosphate-buffered saline; PBS), 250 µM, 1000 µM and 10 mM miltefosine induced a dose dependent inhibition of fungal growth. B. subtilis seeded agar was then used to evaluate possible bactericidal activity. The positive control, a penicillin/streptomycin mixture, as well as 1 mM and 10 mM miltefosine induced significant growth inhibition (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these results confirmed earlier reports on the anti-fungal and anti-bacterial activity of miltefosine15,23.

Miltefosine induced in vitro C. albicans and B. subtilis growth inhibition and in vivo differences in post-treatment myco- and microbiome composition. Right side photographs show agar disk diffusion assays with C. albicans (A) and B. subtilis (B). Arrows indicate direction of miltefosine concentration series (50, 250, 1000 and 10000 µM). Controls: phosphate buffered solution (PBS), nystatin (nyst) and penicillin/streptomycin (p/s). Histograms (A,B) show the average diameter of resulting halos (mean +/− SD, n = 3, ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc test). Visualization of the fecal myco- and microbiome of maternally separated rats subjected to vehicle or miltefosine is shown in (C,D) respectively. The Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index was used to generate the left side dendrograms and right side non-metric multidimensional scaling plots.

Miltefosine treatment modulates the intestinal microbiota in maternal separated rats

The in vitro fungicidal and bactericidal properties of miltefosine prompted us to explore whether successful miltefosine treatment in the maternal separation model associated with intestinal myco- and microbiome differences. We performed high-throughput rDNA sequencing of fungal ITS-1 and bacterial ribosomal 16S genes. Amplicons were generated with DNA isolated from fecal pellets of vehicle treated and miltefosine (10 mg/kg/day) treated maternal separated rats, obtained on day 8 post treatment. One DNA sample of the vehicle group did not generate sufficient amount of sequencing reads for mycobiome analysis.

Hierarchical clustering based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index and the UPGMA algorithm was performed on classified fungal species. The resulting dendrogram (left panel Fig. 2C) showed two main clusters. The upper cluster contained 7 (out of 8) vehicle treated and 2 (out of 9) miltefosine treated maternally separated rats. The lower cluster contained 1 vehicle treated and 7 miltefosine treated maternally separated rats. Similar results were obtained by non-metric multidimensional scaling (right panel Fig. 2C). Spatial patterns obtained with this ordination technique revealed two diffuse but separate clusters for vehicle and miltefosine treated rats. One way PERMANOVA multivariate statistics indicated a significant difference between groups (p = 0.0009, F = 6.6). To compare the bacterial microbiome of maternally separated rats treated with either miltefosine or vehicle, we again performed clustering based on the bray Curtis dissimilarity index and UPGMA algorithm. Compared to the mycobiome analysis, the resulting dendrogram (left panel Fig. 2D) showed less clear separation into treated and untreated clusters. Nevertheless, non-metric multidimensional scaling (right panel Fig. 2D) revealed differential spatial patterns for the two treatment groups. One way PERMANOVA showed significant difference between groups (p = 0.0001, F = 4.1). Collectively, our data suggest that miltefosine treatment modulates both the fecal myco- and microbiome.

Miltefosine affects in situ mast cell staining intensity in colonic mucosa

Although the in vivo effect of miltefosine may depend on mycobiome and microbiome modulation, a direct effect on mast cells may also be relevant16,17,18,19. We performed Toluidine Blue stainings on colonic mucosa of vehicle and miltefosine treated maternal separated rats, and assessed differences in mast cell (granule)-staining intensity as indirect measure for in vivo mast cell degranulation (example stainings in Fig. 3A). Upon miltefosine treatment, we observed higher number of darkly stained mast cells and lower number of mast cells with medium staining intensity (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that post-stress mast cell degranulation was partly prevented by miltefosine treatment.

The % of intensely stained mast cells was higher in miltefosine treated tissues. Arrows in left side photographs (A) indicate representative examples of different mast cell staining intensities obtained with Toluidine Blue. (B) Shows % mucosal mast cells per staining intensity when comparing tissue sections of miltefosine and vehicle treated maternal separated rats. Data are in median & range, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Miltefosine affects in vitro TRPV1 activation by capsaicin

The TRPV-1 ion channel, sensitized via the histamine-1 receptor, is an essential nociceptor in the rat maternal separation model and IBS patients5,6,10. Because the opening properties of TRPV1 are lipid raft dependent, the analgesic effect of miltefosine may partly result from altered TRPV1 gating22,26. We first addressed this possibility in an in vitro model system. Comparing wildtype SH-SY5Y and TRPV1 transfected SH-SY5YhTRPV1 neuroblastoma cells, we showed dose-dependent capsaicin-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels in TRPV1 transfected but not in wildtype cells (Fig. 4A). Based on this experiment, the 32 nM capsaicin concentration was used in further investigations. To confirm strict TRPV1 dependence of the capsaicin response, SH-SY5YhTRPV1 cells were then pre-incubated with SB-70549827. This selective TRPV1 antagonist prevented the capsaicin-induced increase of cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 4B). Next, SH-SY5YhTRPV1 cells were pre-incubated with different concentrations of miltefosine, which dose-dependently decreased capsaicin-induced TRPV1 activation (Fig. 4C).

Miltefosine interfered with in vitro and in vivo capsaicin-induced TRPV1 activation. (A) Intracellular free calcium levels in response to different dosages of capsaicin in wildtype- and TRPV-1 transfected SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. (B) Capsaicin-induced activation of SH-SY5YhTRPV1 cells in the presence of a specific TRPV1 antagonist (SB-705498). (C) Capsaicin-induced activation of SH-SY5YhTRPV1 cells, pre-incubated with different dosages of miltefosine (mean +/− SD, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s post hoc test). (D) Schematic representation of experiments performed in the intracolonic capsaicin model and results of colorectal distensions in this model. Results are given as area under the curve of the relative response to distension (mean +/− SD, n = 9–10, ***P < 0.001, Repeated Measures one-way ANOVA, Sidak’s post hoc test).

In vivo TRPV1 dependent visceral hypersensitivity is prevented by miltefosine treatment

TRPV1 activation is highly relevant in post stress visceral hypersensitivity of the maternal separation model6. However, from the results shown in Fig. 1, it cannot be dissected whether or not TRPV1 was an in vivo target for miltefosine. Earlier, we administered intracolonic capsaicin to nonhandled Long Evans rats and showed that the resulting visceral hypersensitivity is strictly TRPV1 dependent24. Here, we first subjected normal Long Evans rats to a 1 week miltefosine treatment protocol (gavage 10 mg/kg/daily) and then applied 0.1% intracolonic capsaicin. The experimental setup of the experiment is depicted on the right side of Fig. 4D. In vehicle treated rats, capsaicin induced an enhanced response to colonic distension that was not observed when rats were pretreated with miltefosine. These findings suggest that miltefosine’s in vivo mode of action may involve targeting of TRPV1.

Discussion

Treatment of IBS is challenging due to the heterogeneous nature of the disorder and, perhaps as a result thereof, lack of truly efficacious therapies. In at least part of the IBS patients, abdominal pain may arise due to immune recognition of an aberrant gut mycobiome. In response, mast cells release histamine and, via the histamine 1 receptor, sensitize TRPV1 on afferent sensory neurons leading to abdominal pain4,5,6,9,10. In search for novel treatment options, we identified miltefosine as a candidate drug because it reversed post stress visceral hypersensitivity in the IBS-like rat model of maternal separation. In follow up experiments we showed that it may have targeted several of the different mechanisms leading to fungal-induced visceral hypersensitivity (schematic overview in Fig. 5). In line with miltefosine’s fungicidal and bactericidal activity, reversal of visceral hypersensitivity associated with altered gut microbiome composition. In addition, miltefosine affected stress-induced degranulation of mucosal mast cells. Finally, this drug inhibited TPRV1 activation in TRPV1 transfected neuroblastoma cells, and prevented in vivo capsaicin-induced TRPV1 activation and resulting visceral hypersensitivity in normal rats. Thus, miltefosine may exert its analgesic effect by acting on 3 different levels of mycobiome-induced visceral hypersensitivity.

Miltefosine-targets identified in the maternal separation model. Miltefosine affected the fecal myco- and microbiome (1), mast cell degranulation (2) and the TRPV1 ion channel (3). Effects on the histamine 1 receptor (H1R) may have been relevant as well but were not addressed in the current investigations.

Similar to any other animal model, the maternal separation model in rat has its limitations when trying to mimic a complex and enigmatic disorder like IBS. Nevertheless, targets identified in earlier pre-clinical investigations, i.e. mast cells and the histamine 1 receptor, were successfully translated to human5,6,9,10. Therefore, we used this rat model to assess whether orally administered miltefosine, which crosses the intestinal epithelium by a non-specific passive paracellular pathway28, should be a drug candidate to alleviate abdominal pain in IBS. Previous investigations showed fungicide-mediated reversal of post stress visceral hypersensitivity in maternal separated rats. Maternal separated and nonhandled Long Evans rats also differed in gut mycobiome composition, and fecal transfer experiments indicated that the observed mycobiome dysbiosis was relevant for visceral hypersensitivity4. Thus, compounds capable of inducing mycobiome changes may also affect visceral hypersensitivity. Indeed, miltefosine treatment led to reversal of hypersensitivity while the post treatment mycobiome of miltefosine- and vehicle treated rats differed. Whether these mycobiome associations were causally relevant cannot be deduced from the current data. Yet, the fluconazole/nystatin induced reversal of hypersensitivity that we showed earlier, also associated with compositional changes of the gut mycobiome4. In addition, the miltefosine findings are reminiscent of results obtained with a mixture of essential oils from Mentha x piperita L. and Carum carvi. The main components of these oils are menthol and (+)-carvone respectively. Both components were published to have fungicidal activity which we confirmed by agar disk diffusion assays29,30. Indeed, when maternal separated rats were treated with the oil combination, reversal of hypersensitivity associated with a shift in mycobiome composition31. In parallel with these essential oil results, miltefosine treatment not only led to fungal but also bacterial microbiome changes. Because previous experiments showed an essential role for immune recognition of fungal β-glucans, we suggest that the bacterial microbiome is not the main cause for visceral hypersensitivity in these animals4. Alterations of the bacterial microbiome may however also affect the gut mycobiome32, and it cannot be excluded that initial bactericidal effects of miltefosine led to secondary but relevant mycobiome changes.

In the maternal separation model, gut mycobiome dysbiosis is essential for the activation of mast cells which eventually leads to visceral hypersensitivity4,5,6. Others have shown that miltefosine is capable of inhibiting in vitro mast cell activation and successfully used this compound as a therapeutic intervention strategy for mast cell mediated diseases16,17,18,19. In order to further expand knowledge on possible in vivo targets of miltefosine we mainly focused on mechanisms and cell types other than mast cells. We did perform however in situ Toluidine Blue stainings that suggested a lower level of degranulation in miltefosine treated rats. Whether this was due to direct targeting of mast cells, or an indirect effect via microbiome modulation cannot be concluded from this limited evaluation. One mechanism via which miltefosine may have affected mast cells directly is via insertion into lipid rafts13,18,20. These rafts provide the optimal microenvironment for ligand receptor interactions and subsequent recruitment of cell signaling molecules. Moreover, in case of ion channels, lipid rafts can regulate channel function21,33. Using a selective TRPV1 antagonist, we previously showed an important role for this afferent expressed nociceptive cation channel in post stress visceral hypersensitivity of maternal separated rats6. Others provided evidence that interactions between TRPV1 and lipid raft interfaces regulate its gating properties22,26. Indeed, our in vitro results showed that selective capsaicin-induced TRPV1 activation can be inhibited by miltefosine treatment. The latter suggests that miltefosine may have targeted TRPV1 in the maternal separation model as well. Unfortunately however, we are unable to assess the relative contributions, if any, of miltefosine mediated mycobiome-, mast cell- and TRPV1 modulation in the maternal separation setting. Nevertheless, results obtained with the intracolonic capsaicin model confirmed that miltefosine is capable of interfering with in vivo TRPV1 activation. Concerning the role of this ion channel it is important to note that histamine 1 receptor ligation leads to sensitization of TRPV1 and subsequent visceral hypersensitivity in IBS patients10. Because sensitization depends on intracellular signaling pathways, it can be envisaged that TRPV1 and the histamine 1 receptor translocate to the same lipid rafts for optimal interaction. Although our previous investigations showed the relevance of the histamine 1 receptor in the maternal separation model5, we did not address whether miltefosine also interfered with this TRPV1 sensitization mechanism.

Because miltefosine is not specifically targeting TRPV1 containing lipid rafts, signaling pathways not necessarily relevant to abdominal pain may have been affected as well. The cell membrane however, holds many different types of highly dynamic and coexisting rafts with associated proteins34 and miltefosine microdomain affinity may differ according to dissimilarities in composition. Although this suggests that not all raft assemblies and associated events were targeted to the same extent, unwanted side effects should be considered. During a 4 week, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial, Magerl et al. tested the use of orally administered miltefosine in chronic spontaneous urticaria16. In this mast cell and histamine dependent skin condition, the urticaria-activity-score levels and number of weals were substantially more reduced in miltefosine treated patients when compared to placebo treatment. The highest daily treatment dose was 150 mg (average patient weight 84.2 kg), which resembles the 1 mg/kg dose used in the maternal separation model. Although no serious adverse events were reported, mild to moderate adverse events, including nausea and vomiting, were frequent in miltefosine and placebo treatment groups. In addition, beneficial effects of miltefosine over placebo were lost within four weeks after discontinuation of treatment. It can be envisaged that also in IBS long term miltefosine treatment may be needed for a continued effect on TRPV1 dependent pain, but this is not preferable considering the unwanted side effects. Alternatively, miltefosine may be used as a lead compound for the development of drugs effectively modifying TRPV1 responses in the absence of side effects. Yet, this contradicts our original intension of repurposing an existing drug for IBS therapy. Knowing however that miltefosine targets the gut microbiome as well, we suggest that short term treatment should be considered in order to induce a favorable reset of the mycobiome. Our previous results suggested that this can also be achieved with fungicides like fluconazole and nystatin, which are clinically used to treat fungal infections4. Fungal resistance against these compounds is however on the rise, and using them for a non-lethal but highly prevalent disorder like IBS may further shorten their clinical life span35. Since this would lead to a further increase of infection related deaths, alternative compounds like miltefosine should be considered for IBS therapy. Prior to embarking on patient studies however, the long-term persistence of miltefosine treatment-induced mycobiome changes should be monitored in a relevant preclinical setting, preferably in rats with humanized IBS gut micro/mycobiome. In case such results are sufficiently gratifying, we suggest that future clinical trials monitor post treatment symptom improvement and duration thereof, and correlate these results to persistence of mycobiome changes.

Abdominal pain in IBS is an unmet clinical need, and development of novel drugs is highly time consuming and costly. The recent identification of novel targets made it possible to evaluate an existing non-selective but FDA approved drug with known safety profile. Treatments with so-called ‘dirty drugs’ are often avoided. However, off target effects can be used in a meaningful manner, because they enable repurposing of existing therapeutic compounds to other disorders11. Moreover, promiscuous drugs might be more effective than single target drugs11,36. In an animal model with proven predictive value for IBS, we showed that miltefosine changed the gating properties of the nociceptor TRPV1 and affected mast cell activation and the gut mycobiome. Our results suggest that miltefosine should be evaluated for the treatment of abdominal pain in IBS.

Methods

Animals

Long-Evans rats (Harlan, Horst, The Netherlands) used for the current manuscript (n = 7–10/group), were bred at our local animal facility (Amsterdam UMC, Location AMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). All rats shared the same room and were kept in open cages. Research was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of the AMC/University of Amsterdam (Reference Protocol Number 100998).

Measurement of the visceromotor response to colonic distension and data analysis

Visceral hypersensitivity in patients is diagnosed as an increased sensitivity to rectal distension, contributing to abnormal perception of pain and discomfort3. During distensions, self-rating questionnaires (i.e. visual analogue score) are often used to evaluate pain scores, but these cannot be used in rat. However, due to a spinal reflex, colorectal distensions in rats will induce abdominal muscle contractions (the visceromotor response) that we quantified by electromyography (EMG) recording37. To quantitate the absolute response to colorectal distension, EMG data obtained during 20 second tracing periods, prior to distension and during distension, were extracted from the raw data sets, properly processed and subtracted. Next, the response to the first maximum volume distension (i.e. pre-stress or pre-capsaicin 2 mL distension) was defined as the 100% response, and all other responses of the same animal were related to this (as such, the post-stress maximum-volume response of a maternal separated rat will most likely be higher than 100%). The AUC of these relative responses was calculated for individual rats and used for statistical analyses. For extensive description and technical details of this technique and data analysis, please refer to our earlier publications4,5,6,25.

Colonic distension protocol

Distensions were performed at adult age (≥4 months) with a latex balloon (Ultracover 8F, International Medical Products BV, Zutphen, The Netherlands) and carried out as described before4,5,6,25. In short, after insertion of the balloon-catheter under short isoflurane anesthesia, rats were allowed to recover for 20 minutes. Next, the balloon was distended with graded volumes of water (1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mL). During maximum distension, length and diameter of the balloon were 18 and 15 mm, respectively. After each 20 sec distension period, water was quickly removed and rats were allowed to an 80 sec resting period.

Post water avoidance (WA) miltefosine treatment in the maternal separation model

In humans, early adverse life events are associated with IBS at adult age and stress is a trigger for visceral hypersensitivity in IBS patients38,39. These features of IBS are mimicked in the maternal separation model where Long Evans rats are subjected to neonatal maternal separation, followed by an acute WA-stress at adult age. The combined insults were shown to result in post stress visceral hypersensitivity to colorectal distension that is not observed when nonhandled rats are subjected to WA25. For the current experiments, dams were separated from their pups for a period of 3 hours per day from post-natal day 2 to 14. During separation, the dam was placed in a different room while the litter remained in its own cage, placed upon a heat mat to maintain body temperature of the pups. Nonhandled control rats were nursed normally. Pups were weaned at postnatal day 22, and further experiments were carried out at a minimum age of 4 months. Distension protocols were performed pre-WA, 24 hours post-WA and post 7 days treatment. During 1 hour WA, rats were placed on a pedestal surrounded by water4,5,6,25. Miltefosine (JADO Technologies, Dresden, Germany) was dissolved in demineralized water and administered once daily by oral gavage, starting 30 minutes after the first post-WA distension protocol. Maternally separated rats received vehicle or 0.1, 1 or 10 mg miltefosine/kg daily, nonhandled rats received vehicle or 10 mg miltefosine/kg daily. A schematic representation of these experiments is given in Fig. 1A. Our dosing strategy was based on a successful clinical trial performed in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. In this trial, oral miltefosine medication was, depending on tolerability and timing in the 4 weeks treatment protocol, 0.6, 1.2 or 1.8 mg/kg/daily16.

Prophylactic miltefosine treatment in a rat model of intracolonic capsaicin

Investigations in the maternal separation model and IBS patients showed the relevance of the TRPV1 cation channel for visceral hypersensitivity6,10. In an earlier investigation, we used the specific TRPV1-antagonist SB-705498 to show that intracolonic capsaicin-induced visceral hypersensitivity is strictly TRPV1 dependent24. Here we used the same capsaicin model to address the possible TRPV1 modulating capacity of miltefosine. After performing a baseline distension protocol at day 0, miltefosine (10 mg/kg) or vehicle were administered daily per oral gavage. A second distension protocol was then carried out at day 6. Subsequently, capsaicin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was administered under short isoflurane anesthesia. First we applied Vaseline (Boots Healthcare, Hilversum, The Netherlands) to the perianal area to avoid stimulation of somatic areas. Next, 100 µL 0.1% capsaicin (dissolved in 10% ethanol, 10% Tween-80, 80% saline) was given through a fine cannula with a rounded tip inserted rectally, 2 cm from the anus. Animals were allowed to recover for 90 min, after which the last distension protocol was performed. A schematic representation of the intracolonic capsaicin protocol is given in Fig. 4D.

DNA extraction

In our previous investigations we compared the fecal mycobiome of nonhandled and maternally separated rats and observed profound differences between groups4. In the present investigations we compared the myco- and microbiome of maternally separated rats treated with either vehicle or miltefosine (10 mg/kg daily). DNA was isolated from fecal pellets that were collected directly from the anus on day 8 of the treatment protocol and stored at −80 °C until use. Importantly, isolation of fungal/yeast DNA requires more harsh methods than isolation of bacterial DNA. We used a lyticase-based method to catalyze fungal cell lysis, exact details of which are described earlier4. Isolated DNA was then used for ITS-1 as well as 16S sequencing.

Fungal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions sequencing and visualization of results

Preparation of fungal amplicons was performed as described previously4. In summary, a two-step PCR was designed: the first PCR amplified ITS-1 regions, the second PCR generated Nextera XT tagmentation-compatible ITS-1 fragments40. These PCR products were additionally amplified (10 cycles, Ta = 49 °C). Reaction products were cleaned, and 8 bp Illumina sequencing adapters were ligated according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Nextera XT Index Kit; Illumina, San Diego, CA). Subsequently, barcoded products were quantified, and pooled at equal concentrations. After gel purification (Qiaquick spin kit; Qiagen), pooled samples were sequenced (250 bp paired-end sequencing, MiSeq; Illumina).

Raw fastq files were processed by demultiplexing, quality fiterling, and further analysed using Mothur and implanted modules41. The RDP-II Naïve Bayesian Classifier was used to taxonomically classify unique sequences42, using a 60% confidence threshold against the UNITE database (v7)43. The Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index was used for classical clustering (UPGMA algorithm) to assess and visualize distances between ITS compositions. PAST (v3.034) was used to generate nun-metric multidimensional scaling plots. One-way permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was done on the resulting Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. All raw sequencing data will be uploaded in the European Nucleotide Archive.

Bacterial 16S sequencing and visualization of results

The hypervariable V4 region of the 16S-rRNA gene of the rat fecal DNA was amplified, sequenced by Illumina MiSeq (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and processed using modules implemented in the Mothur software platform, version 1.31.2 and Btrim41,44. First, reads were checked and quality trimmed (quality threshold 30) by using the ‘Btrim’ command. Next, read pairs were merged (‘make.contigs’), and merged reads with a length of 240–260 base pairs were aligned (‘align.seqs’) to a SILVA reference database. Visualization based upon Bray-Curtis dissimilarity was carried out analogous to ITS visualization described above.

Agar disk diffusion assay to address antifungal and antibacterial properties of miltefosine

The antifungal and antibacterial qualities of miltefosine, were assayed at 4 different concentrations (50, 250 and 1000 µM and 10 mM). Methodology was similar to our earlier publication31 and is given in short only. To test fungicidal activity, C. albicans was diluted in top agar, spread in petri dishes and left to solidify. Next, 3 mm holes were punched and filled with 8 µl miltefosine, vehicle or the fungicide nystatin that was used as positive control. Plates were incubated 24 to 48 hour before the halo of inhibition, visible as a zone of clearing around a punched hole, was measured (diameter in mm). To test bactericidal activity, B. subtilis was diluted in 0.3% TBS/1% Agar/0.02% Tween, spread in petri dishes and left to solidify. Next, 3 mm holes were made and filled with miltefosine, vehicle or positive control (penicillin/streptomycin mixture containing 1000 units/ml and 1000 µg/ml respectively). After diffusion into the plates, dishes were covered with a top layer and further incubated for 18 to 24 hours, after which the halo-diameter was measured.

Semi quantitative assessment of in situ mast cell activation status

Mucosal mast cells were stained following a staining protocol described by Wingren and Enerbäck45. As the distension took place in the distal part of the colon, paraffin sections were cut from proximal colon (thickness 4 μm) in order to rule out any role for distension-induced mast cell degranulation. Sections were processed for staining and incubated for 6 days in Toluidine Blue in 0.5N HCL (pH = 0.5). To semi-quantitatively assess mast cell activation, every 5th section, with a total of 5 sections per rat, was evaluated in a double-blind manner. A total of 50 mast cells were counted per section and each mast cell was categorized as either dark staining intensity, medium staining intensity or light staining intensity (example stainings are shown in Fig. 3A). Results of the 5 individual sections were averaged per rat to give a representative outcome. Final results are given as a percentage per category of total mast cells counted.

Assessment of in vitro TRPV1 activation and modulation, by fluorimetric measurement of intracellular free calcium

Capsaicin-induced activation of TRPV1 and modulation thereof was monitored with the help of the Indo-1 AM calcium indicator (Invitrogen, Bleiswijk, the Netherlands). In short, TRPV1 recombinant SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5YhTRPV1, kindly provided by GlaxoSmithKline, Stevenage, UK)46 were detached with the aid of trypsin free cell dissociation buffer (Gibco, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands), resuspended in HEPES-buffered HBBS and incubated with 10 μg/ml Indo-1 AM (30 minutes, 37 °C). Next, cells were washed and rested (30 minutes, room temperature) to allow complete de-esterification of intracellular esters. Hereafter, cells were re-suspended to 107 cells/ml, supplemented with 1.2 mM CaCl2 and allowed to adapt to 37 °C for 10 minutes. Miltefosine (50, 70, 100 µM) was added 10 minutes before stimulating cells with capsaicin (32 nM, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Similar to our earlier investigations6,24, we used the selective TRPV-1 antagonist SB-705494 (5 µM, kind gift of GlaxoSmithKline)27 as positive control for TRPV1 inhibition. Optimal dosage of capsaicin was first established using wildtype SH-SY5Y and SH-SY5YhTRPV1 cells. Analyses were performed with NOVOstar analyzer (BMG Labtech GmbH, Offenburg, Germany; excitation, 320 nm; emission, 405 nm and 520 nm). Cytosolic free calcium/calcium influx is represented as the change in fluorescence at 405 nm divided by that at 520 nm = Δ405/520.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.03, Graphpad software, San Diego, USA). All data, excluding myco- and microbiome compositions, were tested for normality using D’Agostino & Pearson normality test. Visceromotor response data were analyzed with the Repeated Measures one-way ANOVA, and tested post-hoc with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Anti-microbial activity and calcium measurement data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. Toluidine Blue staining intensity data were analyzed with the Mann Whitney U test, comparing the percentages of mast cells in each group.

References

Drossman, D. A. et al. International Survey of Patients With IBS Symptom Features and Their Severity, Health Status, Treatments, and Risk Taking to Achieve Clinical Benefit. Journal of clinical gastroenterology 43, 541–550, https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e318189a7f9 (2009).

Morgan, B. Drug development: A healthy pipeline. Nature 533, S116–117, https://doi.org/10.1038/533S116a (2016).

Keszthelyi, D., Troost, F. J. & Masclee, A. A. Irritable bowel syndrome: methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology. Methods to assess visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 303, G141–154, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00060.2012 (2012).

Botschuijver, S. et al. Intestinal Fungal Dysbiosis Is Associated With Visceral Hypersensitivity in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Rats. Gastroenterology 153, 1026–1039, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.004 (2017).

Stanisor, O. I. et al. Stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity in maternally separated rats can be reversed by peripherally restricted histamine-1-receptor antagonists. PloS one 8, e66884, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066884 (2013).

van den Wijngaard, R. M. et al. Essential role for TRPV1 in stress-induced (mast cell-dependent) colonic hypersensitivity in maternally separated rats. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 21, 1107–e1194, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01339.x (2009).

Barbara, G. et al. Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 126, 693–702, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.055 (2004).

Barbara, G. et al. Mast cell-dependent excitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 132, 26–37, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.039 (2007).

Klooker, T. K. et al. The mast cell stabiliser ketotifen decreases visceral hypersensitivity and improves intestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 59, 1213–1221, https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.213108 (2010).

Wouters, M. M. et al. Histamine Receptor H1-Mediated Sensitization of TRPV1 Mediates Visceral Hypersensitivity and Symptoms in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 150, 875–887 e879, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.034 (2016).

Bastos, L. F. & Coelho, M. M. Drug repositioning: playing dirty to kill pain. CNS drugs 28, 45–61, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-013-0128-0 (2014).

Dorlo, T. P., Balasegaram, M., Beijnen, J. H. & de Vries, P. J. Miltefosine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of leishmaniasis. J Antimicrob Chemother 67, 2576–2597, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dks275 (2012).

van Blitterswijk, W. J. & Verheij, M. Anticancer mechanisms and clinical application of alkylphospholipids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1831, 663–674, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.10.008 (2013).

Biswas, C. et al. Functional disruption of yeast metacaspase, Mca1, leads to miltefosine resistance and inability to mediate miltefosine-induced apoptotic effects. Fungal genetics and biology: FG & B 67, 71–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fgb.2014.04.003 (2014).

Widmer, F. et al. Hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine) has broad-spectrum fungicidal activity and is efficacious in a mouse model of cryptococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50, 414–421, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.50.2.414-421.2006 (2006).

Magerl, M. et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and efficacy of miltefosine in antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV 27, e363–369, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04689.x (2013).

Maurer, M., Magerl, M., Metz, M., Weller, K. & Siebenhaar, F. Miltefosine: a novel treatment option for mast cell-mediated diseases. The Journal of dermatological treatment 24, 244–249, https://doi.org/10.3109/09546634.2012.671909 (2013).

Rubikova, Z., Sulimenko, V., Paulenda, T. & Draber, P. Mast Cell Activation and Microtubule Organization Are Modulated by Miltefosine Through Protein Kinase C Inhibition. Frontiers in immunology 9, 1563, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01563 (2018).

Weller, K. et al. Miltefosine Inhibits Human Mast Cell Activation and Mediator Release Both In Vitro and In Vivo. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 129, 496–498, https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2008.248 (2009).

Heczkova, B. & Slotte, J. P. Effect of anti-tumor ether lipids on ordered domains in model membranes. FEBS letters 580, 2471–2476, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.079 (2006).

Varshney, P., Yadav, V. & Saini, N. Lipid rafts in immune signalling: current progress and future perspective. Immunology 149, 13–24, https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12617 (2016).

Saghy, E. et al. Evidence for the role of lipid rafts and sphingomyelin in Ca2+-gating of Transient Receptor Potential channels in trigeminal sensory neurons and peripheral nerve terminals. Pharmacological research 100, 101–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2015.07.028 (2015).

Llull, D., Rivas, L. & Garcia, E. In vitro bactericidal activity of the antiprotozoal drug miltefosine against Streptococcus pneumoniae and other pathogenic streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51, 1844–1848, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01428-06 (2007).

van den Wijngaard, R. M. et al. Possible role for TRPV1 in neomycin-induced inhibition of visceral hypersensitivity in rat. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 21, 863–e860, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01287.x (2009).

Welting, O., Van Den Wijngaard, R. M., De Jonge, W. J., Holman, R. & Boeckxstaens, G. E. Assessment of visceral sensitivity using radio telemetry in a rat model of maternal separation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 17, 838–845, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00677.x (2005).

Szoke, E. et al. Effect of lipid raft disruption on TRPV1 receptor activation of trigeminal sensory neurons and transfected cell line. European journal of pharmacology 628, 67–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.11.052 (2010).

Rami, H. K. et al. Discovery of SB-705498: a potent, selective and orally bioavailable TRPV1 antagonist suitable for clinical development. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 16, 3287–3291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.030 (2006).

Menez, C., Buyse, M., Dugave, C., Farinotti, R. & Barratt, G. Intestinal absorption of miltefosine: contribution of passive paracellular transport. Pharmaceutical research 24, 546–554, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-006-9170-7 (2007).

Morcia, C., Malnati, M. & Terzi, V. In vitro antifungal activity of terpinen-4-ol, eugenol, carvone, 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) and thymol against mycotoxigenic plant pathogens. Food additives & contaminants. Part A, Chemistry, analysis, control, exposure & risk assessment 29, 415–422, https://doi.org/10.1080/19440049.2011.643458 (2012).

Sokovic, M. D. et al. Chemical composition of essential oils of Thymus and Mentha species and their antifungal activities. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 14, 238–249, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules14010238 (2009).

Botschuijver, S. et al. Reversal of visceral hypersensitivity in rat by Menthacarin((R)), a proprietary combination of essential oils from peppermint and caraway, coincides with mycobiome modulation. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 30, e13299, https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13299 (2018).

Sam, Q. H., Chang, M. W. & Chai, L. Y. The Fungal Mycobiome and Its Interaction with Gut Bacteria in the Host. International journal of molecular sciences 18, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020330 (2017).

Dart, C. Lipid microdomains and the regulation of ion channel function. The Journal of physiology 588, 3169–3178, https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191585 (2010).

Sezgin, E., Levental, I., Mayor, S. & Eggeling, C. The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 18, 361–374, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2017.16 (2017).

Robbins, N., Caplan, T. & Cowen, L. E. Molecular Evolution of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Annual review of microbiology 71, 753–775, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-micro-030117-020345 (2017).

Frantz, S. Drug discovery: playing dirty. Nature 437, 942–943, https://doi.org/10.1038/437942a (2005).

Christianson, J. A. & Gebhart, G. F. Assessment of colon sensitivity by luminal distension in mice. Nature protocols 2, 2624–2631, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.392 (2007).

Park, S. H. et al. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with irritable bowel syndrome and gastrointestinal symptom severity. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 28, 1252–1260, https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12826 (2016).

Posserud, I. et al. Altered visceral perceptual and neuroendocrine response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome during mental stress. Gut 53, 1102–1108, https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.017962 (2004).

Bokulich, N. A. & Mills, D. A. Improved selection of internal transcribed spacer-specific primers enables quantitative, ultra-high-throughput profiling of fungal communities. Applied and environmental microbiology 79, 2519–2526, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03870-12 (2013).

Schloss, P. D. et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Applied and environmental microbiology 75, 7537–7541, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01541-09 (2009).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Applied and environmental microbiology 73, 5261–5267, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00062-07 (2007).

Abarenkov, K. et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi–recent updates and future perspectives. The New phytologist 186, 281–285, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03160.x (2010).

Kong, Y. Btrim: a fast, lightweight adapter and quality trimming program for next-generation sequencing technologies. Genomics 98, 152–153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.05.009 (2011).

Wingren, U. & Enerback, L. Mucosal mast cells of the rat intestine: a re-evaluation of fixation and staining properties, with special reference to protein blocking and solubility of the granular glycosaminoglycan. The Histochemical journal 15, 571–582, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01954148 (1983).

Lam, P. M. et al. Activation of recombinant human TRPV1 receptors expressed in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells increases [Ca(2+)](i), initiates neurotransmitter release and promotes delayed cell death. Journal of neurochemistry 102, 801–811, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04569.x (2007).

Acknowledgements

W.J.D.J. is supported by Marie Curie ETN Grant No. 641665. S.B. and S.v.D. were supported by The Netherlands Digestive Diseases Foundation, Project No. 1CDP005. I.v.T. was supported by an internal Tytgat Institute grant. Z.Y. was sponsored by the China Exchange Programme of The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW, Project Number 11CDDP005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., S.v.D., I.v.T., R.O.E., W.d.J. and R.v.d.W. designed experiments; S.B., S.v.D., I.v.T., R.S., A.S., Z.Y., D.M.F., O.W., S.H. and F.S. conducted in vitro experiments and preclinical research; S.B. and F.S. performed ITS and 16S sequencing, analysis and statistics; G.J. supplied test compounds; all authors contributed to data analysis; S.B., S.v.D., I.v.T. and R.v.d.W. wrote the paper; all authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

W.J.D.J., received consultancy fees from GlaxoSmithKline and research support from Galvani Bioelectronics, GlaxoSmithKline and Mead Johnsson Nutrition Pediatric Institute. Although G.J. used to be employed by JADO Technologies GmbH, there is no competing interest as the interest (JADO) no longer exists and no successor interests exist either (the discovery of anti-inflammatory effects of miltefosine in mastocytosis, atopic dermatitis and urticaria are in the public domain). All other authors declare no financial competing interests. All authors declare no non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Botschuijver, S., van Diest, S.A., van Thiel, I.A.M. et al. Miltefosine treatment reduces visceral hypersensitivity in a rat model for irritable bowel syndrome via multiple mechanisms. Sci Rep 9, 12530 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49096-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49096-y

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.