Abstract

The Mohr-Coulomb (M-C) stress criterion is widely applied to describe the pressure sensitivity of bulk metallic glasses (BMGs). However, this criterion is incapable of predicting the variation in fracture angles under different loading modes. Moreover, the M-C criterion cannot describe the plastic fracture of BMGs under compressive loading because the nominal stress of most BMGs remains unchanged after the materials yield. Based on these limitations, we propose a new generalized M-C strain criterion and apply it to analyze the fracture behaviors of two typical Zr-based BMG round bar specimens under complex compressive loading. In this case, the predicted initial yielding stress is in good agreement with the experimental results. The theoretical results can also describe the critical shear strain and fracture angle of BMGs that are associated with the deformation mode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among current advanced materials, bulk metallic glasses (BMGs) have attracted wide attention and have great applications in functional and structural materials due to their outstanding mechanical, chemical, and physical properties1,2,3,4,5. In particular, metallic glasses have a high strength approaching the theoretical limit and have a uniquely high capacity to store elastic energy6,7,8,9,10. However, due to localized shear bands, the limited global plasticity of BMGs restricts the application of BMGs as a structural material. Thus, many studies in the last two decades were dedicated to overcoming this barrier and understanding the plasticity of BMGs. Many factors and ideas have been proposed to improve the ductility of BMGs, such as the BMG composition11,12,13,14, electrodeposition15, confining pressure16,17, and atomic scale effects18. Moreover, it is also important to investigate the fracture mechanism and fracture criteria of BMGs19,20,21 and to provide safe reference for their potential application. The existing fracture criteria, such as the traditional stress Mohr-Coulomb (M-C) criterion22,23, ellipse criterion24, and hyperbola criterion25, focus on describing the pressure sensitivity of BMGs16,26,27,28. The elastic-perfectly plastic behavior of BMGs under compressive loading is always ignored in these stress criteria because of the limited plasticity of previous BMGs11,29,30. However, the considerable plasticity of newly developed BMGs cannot be ignored; as the cross-sectional area increases under compressive loading, the nominal stress of BMGs remains unchanged, and the Cauchy stress decreases. This finding indicates that the stress criteria cannot accurately predict the failure behaviors of the newly developed BMGs. In addition, the existing criteria usually focus on fracture behavior under simple loading, but materials always suffer complex loading in engineering applications. Moreover, experiments under complex loading show that the macroscopic plasticity of BMGs will be enhanced with increasing superimposed confining pressure16,17. This finding indicates that the loading mode is important to the fracture behavior of BMGs. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a more suitable compression fracture criterion and a method to analyze the fracture behavior of BMGs under complex compressive loading.

Among the criteria introduced above, the M-C stress criterion is widely accepted and applied by scholars because of its simple form and clear physical meaning16,19,21,31. Therefore, we provide a new generalized M-C strain failure criterion for BMGs. By taking a round bar as the research object, the fracture behavior of BMGs under complex compressive loading will be discussed in this paper. According to the stress state shown in Fig. 1, we can assume that the normal of the fracture plane is located at the x1-x3 plane due to the symmetry of the round bar. The confining pressure is proportional to the axial stress: S22 = S33 = ρS11(S11 < 0), where ρ is the proportionality coefficient between the axial stress S11 and the confining pressure S33.

Results

Generalized Mohr-Coulomb strain failure criterion

To describe the fracture behaviors of BMGs under complex compressive loading, the M-C criterion should be improved due to the following aspects:

-

(1)

Compression experiments of round bar specimens of BMGs show that the axial nominal stress S11(as shown in Fig. 1(a)) always remains unchanged once the material yields11,26,32, correspondingly, the Cauchy stress decreases as the cross-sectional area increases. In this case, the relation between the stress state and the strain state of BMGs is no longer one-to-one once the material yields. This finding indicates that the strain state is more suitable than the stress state for predicting the fracture behaviors of BMGs.

-

(2)

The traditional M-C stress criterion is τ = τ0 + μσ, where σand τ are the normal stress and shear stress on the fracture plane, respectively; τ0 is the pure shear strength; and μ is an important constant to measure the influence of normal stress, which is directly related to the frictional (fracture) angle θ (μ = tanθ). However, experiments show that the fractures in BMGs occur along different angles under different loading modes21,31. This finding means that the parameter μ in the traditional M-C criterion should not be a constant but should vary with the loading or deformation mode.

-

(3)

Due to the different production processes, there is a very large gap in the plasticity of different types of BMGs, which should be considered in the new criterion. Hence, to describe the fracture behaviors of BMGs, we propose a generalized M-C strain criterion that can be expressed as

where ε and γ/2 are the normal strain and the shear strain along the fracture plane, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1(b). The strain state (ε,γ/2) is related to the normal strain ε1 and ε3, which can be expressed as \(\gamma /2=({\varepsilon }_{3}-{\varepsilon }_{1})\,\sin \,2\theta /2\) and \(\varepsilon =({\varepsilon }_{3}+{\varepsilon }_{1})/2+({\varepsilon }_{3}-{\varepsilon }_{1})\cos \,2\theta /2\). Here, we define a parameter ρ′ = ε3/ε1 to describe the deformation state, and αC = αC0(1 + ρ′) is a new form of intrinsic pressure-sensitivity parameter, which is related to the deformation mode. Note that γCf is the critical shear strain, which describes the ability of materials to resist shear deformation and can be approximately expressed as

where γC0 is the critical shear strain for ρ′ = −1 and β is a material constant. The generalized M-C strain criterion (Eq. (1)) describes the shear failure accompanied by the influence of pressure sensitivity. The fracture of BMGs occurs once the shear strain along the fracture plane reaches the critical value γCf.

The new generalized M-C strain criterion predicts the fracture behaviors of BMGs by the strain state along the fracture plane. However, the strain state along the fracture plane cannot be directly obtained in engineering applications. Thus, it is also important to predict the location of the fracture plane under different deformation modes. Our previous studies provide a universal formula that predicts the location of the most dangerous plane by seeking the tangent to the fracture line33,34. This formula can be rewritten as

F(ε,γ/2) is the fracture function, which can be expressed as

Substituting the above equation into Eq. (3), we can obtain the fracture angle for different deformation modes, which can be expressed as

For the new criterion (Eq. (1)), the dependence between the shear strain γ/2 and the normal strain ε is no longer linear. Specifically, the material parameters in the traditional M-C stress criterion are independent of the loading mode, but these parameters are related to the deformation mode according to the current criterion. As illustrated in Fig. 2, two M-C lines (dashed lines) correspond to two different deformation modes (point A represents the pure shear state and point B represents one of the general cases). The fracture occurs at the time that the critical strain in the Mohr’s circle is tangent to the fracture line of the new fracture function F. The fracture angle and the fracture strain state can be obtained from the tangent point. Thus, the new generalized M-C strain criterion is different from the traditional M-C criterion. The new criterion does not directly indicate the fracture curve of BMGs but gives the critical tangent point in the Mohr’s circle for different deformation modes. The complete fracture line shown in Fig. 2 (red line) is the trajectory of the tangent point in different deformation modes.

Yield criterion and constitutive relation

Once we know the strain state of a material, the new criterion can provide a reference for their safety. However, in many cases, we only know the stress state of a material but cannot directly obtain their strain state16,26. Thus, the corresponding constitutive relationship also needs to be discussed. In this paper, we choose the Drucker-Prager (D-P) criterion to describe the yield of BMGs because this criterion considers the influence of triaxial stress (pressure sensitivity) on material yielding. The nominal stress Sij is used to replace Cauchy stress because the Cauchy stress decreases during deformation. The new form of the D-P criterion is

where \({T}_{e}=\sqrt{{T}_{ij}^{\text{'}}{T}_{ij}^{\text{'}}/2}\) is the effective stress, \({T}_{ij}^{\text{'}}={T}_{ij}-{T}_{m}{\delta }_{ij}\) is the deviatoric stress, Tm = Tkk/3 is the mean stress, and the stress tensor Tij = (Sij + Sji)/2. The parameter α represents the pressure sensitivity of yielding, and the yield strength f0 represents the ability of materials to resist yielding under pure shear loading. Both αC and α are pressure-sensitivity parameters, but they correspond to two different mechanical behaviors, fracture and yield, respectively. The plastic deformation of BMGs obeys the plastic normality rule, which indicates the direction of the plastic strain increment. Thus, the strain rate tensor Dij can be written as

where G and K are the elastic shear modulus and the bulk modulus, respectively (the specific derivations are shown in the Methods section).

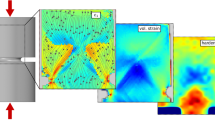

Fracture behaviors of Vit-105 BMGs

With the constitutive relation (Eq. (7)) and the fracture criterion (Eq. (1)), the fracture behaviors of Vit-105 round bars under different loading modes can be obtained. The material constants are shown in Table 1 (additional details about the calculations are provided in the Methods section). The dependence between the fracture strain and the proportionality coefficient ρ is illustrated in Fig. 3. On the one hand, as ρ increases, both the axial elastic strain |ε11e| and the plastic strain |ε11p|continually increase. On the other hand, due to the Poisson effect, the radial elastic strain |ε22e| is a tensile strain when ρ is small, and it will continue to decrease as ρ increases, eventually becoming a compressive strain. The variation in radial plastic strain |ε22p| with respect to ρ is also shown in Fig. 3(b), which exhibits an increasing trend. The shear strain along the fracture plane versus the proportionality coefficient ρ is shown in Fig. 4. Both the elastic strain and the plastic shear strain increase with increasing ρ, and the latter increases faster than the former. The increase in confining pressure is equivalent to exerting a stronger constraint on the specimen; therefore, the specimen requires more deformation to fracture.

Comparison of the theoretical and experimental results of Vit-1 BMG

The complex compressive loading experiments for another typical Vit-1 BMG were reported in the literature16,26. The round bars were 12.7 mm in length and 6.35 ± 0.02 mm in diameter and were subject to quasistatic compression with a preapplied superimposed pressure. The loading method in these experiments is somewhat different from the proportional loading discussed in this paper. However, due to the elastic-perfectly plastic behavior of BMGs, the nominal yielding stress can be determined directly once the material yields. The preapplied hydrostatic pressure does not cause material yielding, and the constitutive relationship in the elastic deformation of the material is independent of the loading path. Thus, the experimental results can be compared directly with the case of proportional loading. The material constants are shown in Table 2, and more experimental data and calculations are shown in the Methods section. The theoretical and experimental results of Vit-1 are in good agreement, as shown in Fig. 5. Specifically, the axial stress and the normal stress on the fracture plane increase significantly with increasing pressure, whereas the fracture angle and the shear stress on the fracture plane remain approximately constant the scope of study.

Analysis results vs. experimental data (Vit-1). (a) Variations in the axial fracture stress with respect to the confining pressure. (b) Variations in the fracture angle with respect to the confining pressure. (c) Variations in the normal stress on the fracture plane with respect to the confining pressure. (d) Shear stress on the fracture plane with respect to the confining pressure.

Discussion

The above results clearly describe the fracture behaviors of BMG round bar specimens under different loading modes. Actually, as a strain criterion, the present fracture criterion can directly predict the fracture behaviors of different deformation states. By substituting Eq. (5) into Eq. (1), the axial fracture strain of the round bar with different deformation modes (ρ′) can be obtained, which can be expressed as

where χ = (1 − ρ′)/(1 + ρ′). The radial strain ε3 can be given by the relation ε3 = ρ′ε1. With the fracture strain and the fracture angle, the fracture strain state along the fracture plane can be derived, and the dependence between the normal strain and the shear strain is illustrated by the red line in Fig. 6. Furthermore, eight blue points are also marked on the red line, which represent the fracture deformation states of the different loading modes (ρ = −0.1, …, 0.7). The Mohr’s circles and the M-C fracture lines shown in Fig. 6 correspond to cases where the material is subjected to uniaxial compression and pure shear loading, respectively. The fracture angle can be obtained from the slope of the M-C lines. The M-C lines in Fig. 6 indicate that the fracture angle tends to decrease with increasing pressure. When the fracture angle is reduced, the shear strain along the fracture plane becomes larger to reduce the inhibiting effect of confining pressure on the material failure. When ρ is small, we also note that the distribution of blue points is denser. In this case, the effect of the loading mode on fracture is not obvious. This result can qualitatively explain why the change in the fracture angle is not obvious in the uniaxial compression experiments with a preapplied superimposed pressure (the maximum value of ρ is 0.23)16.

The analysis above shows that the predictions of the generalized M-C strain criterion strongly depend on the material constants αC and β and the deformation state coefficient ρ′. Though ρ′ is defined as ρ′ = ε3/ε1 to study the fracture behaviors of the round bar in this work, this definition can also be extended to more general cases. The deformation state of materials can always be given by the three principal strains εI > εII > εIII, and the maximum shear strain is determined only by the first principal stain εI and the third principal strain εIII. Thus, the definition of ρ′ in general cases can be expressed as ρ′ = εI/εIII. Moreover, the parameter αC is the intrinsic parameter reflecting the effect of material pressure sensitivity25, which is closely related to the fracture angle. In addition to αC, it is also necessary to deepen the understanding of the meaning of β. We adopt the basic parameters of Vit-105 and then change β to obtain different results, as shown in Fig. 7. The results show that elastic fracture will change to plastic fracture as β increases, which indicates that the parameter β is related to the intrinsic plasticity of materials. Usually, for low values of β, BMGs tend to exhibit brittle fractures with limited macroscopic plasticity, such as La-based BMGs32,35. However, some newly developed BMGs with higher values of β can be made by adjusting the component proportion of BMGs or introducing a second crystalline phase into liquid BMGs11,12,36, providing greater global plasticity under uniaxial compression.

Conclusions

We proposed a new generalized M-C strain criterion to predict the fracture behaviors of BMGs under complex compressive loading. The present strain criterion accounts for both pressure sensitivity and deformation mode. To be more specific, α reflects the pressure sensitivity, whereas the intrinsic material constant β describes the plasticity of different BMGs. To validate this new criterion, we analyzed the fracture behaviors of round bar specimens and compared the theoretical results to the experimental results of typical Vit-1 BMGs. The predicted fracture strength is consistent with the experimental results. This new generalized M-C strain criterion can predict both the fracture strength and the fracture angle, which assists the engineering application of BMG materials.

Methods

Derivation of the constitutive relation

The constitutive relation of BMGs can be obtained by combining the yield criterion and the plastic normality rule. The normality rule gives the direction of plastic strain increment, which can be expressed as

This normality rule is described by the nominal stress. Note that f is the flow potential (Eq. (6)) and λ is a coefficient. By substituting the flow potential into the normality rule, we can obtain a relation between the plastic deformation rate and Tij stress, which can be expressed as

The effective plastic strain rate can be expressed as

Similar results can be found in another paper37. Considering the elastic deformation, the strain rate can be written as shown in Eq. (7).

Material constants of Vit-105 BMG

There are three important constants in the generalized M-C strain criterion: αC0, γC0, and β. Note that αC0 and β can be given by the axial fracture strain ε1 and the fracture angle θ of one deformation mode experiment (ρ′), which can be formulized as

where χ = (1 − ρ′)/(1 + ρ′). The pure shear strain (γC0 = τ0/G = 0.0261), the fracture angle (θuni = 43°) and the uniaxial compressive strain (ε1uni = −5%) can be obtained directly from the experiments31,38. Another important proportionality coefficient ρ′ can be given by calculating the radial strain, which can be obtained by the constitutive relationship (Eq. (7)) of BMGs. We assume that BMGs exhibit elastic-perfectly plastic behavior under different loading modes; therefore, the nominal stress remains unchanged once the material yields (\({\dot{S}}_{11}={\dot{S}}_{33}=0\)). Therefore, according to Eq. (7), the plastic strain rate is

With α = 0.03, the corresponding radial strain can be obtained as ε1uni = 2.31. Finally, other parameters (αC0 = 0.13 and β = 3.23) can be given by these data.

Material constants of Vit-1 BMG

Complex compressive loading experiments for another typical Vit-1 BMG were performed in the literature16,26, and the results are listed in Table 3. The axial fracture stress, the radial fracture stress, and the stress proportionality coefficient ρ can be obtained from these basic data, and the results are listed in Table 4. There are three material constants α, αC0, and β that need to be determined before comparing the theoretical results with the experiments by the new criterion. The pressure-sensitivity constant α in the yield criterion can be obtained by two yield stresses of different loading modes. By substituting the first (uniaxial compression) and third (pressure = 450 MPa) experimental data into the yield criterion (Eq. (6)), one can obtain α = 0.0819 and f0 = τ0 = 1.1 GPa. Moreover, αC0 and β can be obtained by the same method as discussed before. In this part, we chose the fracture strain of the third experimental data (pressure = 450 MPa) to determine these material constants. The axial fracture strain ε1(p=450MPa) = −0.042916, the calculated radial fracture strain ε2(p=450MPa) = 0.0180, and the calculated pure shear strain γC0 = τ0/G = 0.0294. Finally, αC0 = 0.3038 and β = 1.6421 can be obtained.

References

Schuh, C. A., Hufnagel, T. C. & Ramamurty, U. Mechanical behavior of amorphous alloys. Acta Materialia 55, 4067–4109, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2007.01.052 (2007).

Ashby, M. F. & Greer, A. L. Metallic glasses as structural materials. Scripta Materialia 54, 321–326, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2005.09.051 (2006).

Trexler, M. M. & Thadhani, N. N. Mechanical properties of bulk metallic glasses. Progress in Materials Science 55, 759–839, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2010.04.002 (2010).

Demetriou, M. D. et al. A damage-tolerant glass. Nature materials 10, 123 (2011).

Wang, W. H., Dong, C. & Shek, C. H. Bulk metallic glasses. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 44, 45–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mser.2004.03.001 (2004).

Chen, H., He, Y., Shiflet, G. J. & Poon, S. J. Deformation-induced nanocrystal formation in shear bands of amorphous alloys. Nature 367, 541–543 (1994).

Flores, K. M. & Dauskardt, R. H. Local heating associated with crack tip plasticity in Zr–Ti–Ni–Cu–Be bulk amorphous metals. Journal of materials research 14, 638–643 (1999).

Hays, C. C., Kim, C. P. & Johnson, W. L. Microstructure Controlled Shear Band Pattern Formation and Enhanced Plasticity of Bulk Metallic Glasses Containing in situ Formed Ductile Phase Dendrite Dispersions. Physical Review Letters 84, 2901–2904 (2000).

Steif, P. S., Spaepen, F. & Hutchinson, J. W. Strain localization in amorphous metals. Acta Metallurgica 30, 447–455, https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(82)90225-5 (1982).

Xing, L. Q., Li, Y., Ramesh, K. T., Li, J. & Hufnagel, T. C. Enhanced plastic strain in Zr-based bulk amorphous alloys. Physical Review B 64, 180201 (2001).

Schroers, J. & Johnson, W. L. Ductile Bulk Metallic Glass. Physical Review Letters 93, 255506 (2004).

Park, E. S. & Kim, D. H. Phase separation and enhancement of plasticity in Cu–Zr–Al–Y bulk metallic glasses. Acta Materialia 54, 2597–2604 (2006).

Yang, W. et al. Mechanical properties and structural features of novel Fe-based bulk metallic glasses with unprecedented plasticity. Scientific Reports 4, 6233, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06233 (2014).

Das, J. et al. “Work-Hardenable” Ductile Bulk Metallic Glass. Physical Review Letters 94, 205501, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.205501 (2005).

Ren, L. W. et al. Enhancement of plasticity in Zr-based bulk metallic glasses electroplated with copper coatings. Intermetallics 57, 121–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intermet.2014.10.009 (2015).

Caris, J. & Lewandowski, J. J. Pressure effects on metallic glasses. Acta Materialia 58, 1026–1036, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2009.10.018 (2010).

Lu, J. & Ravichandran, G. Pressure-dependent flow behavior of Zr41.2Ti13.8Cu12.5Ni10Be22.5 bulk metallic glass. Journal of Materials Research 18, 2039–2049, https://doi.org/10.1557/JMR.2003.0287 (2003).

Sarac, B. et al. Origin of large plasticity and multiscale effects in iron-based metallic glasses. Nature Communications 9, 1333, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03744-5 (2018).

Schuh, C. A. & Lund, A. C. Atomistic basis for the plastic yield criterion of metallic glass. Nature Materials 2, 449, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat918 (2003).

Xu, B., Falk, M. L., Li, J. F. & Kong, L. T. Predicting Shear Transformation Events in Metallic Glasses. Physical Review Letters 120, 125503, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.125503 (2018).

Zhang, Z. F., He, G., Eckert, J. & Schultz, L. Fracture Mechanisms in Bulk Metallic Glassy Materials. Physical Review Letters 91, 045505, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.045505 (2003).

Donovan, P. E. A yield criterion for Pd40Ni40P20 metallic glass. Acta Metallurgica 37, 445–456, https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(89)90228-9 (1989).

Yu, M.-H. Advances in strength theories for materials under complex stress state in the 20th Century. Applied Mechanics Reviews 55, 169–218, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1472455 (2002).

Zhang, Z. F. & Eckert, J. Unified Tensile Fracture Criterion. Physical Review Letters 94, 094301, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.094301 (2005).

Qu, R. T. & Zhang, Z. F. A universal fracture criterion for high-strength materials. Scientific Reports 3, 1117 (2013).

Lewandowski, J. J. & Lowhaphandu, P. Effects of hydrostatic pressure on the flow and fracture of a bulk amorphous metal. Philosophical Magazine A Volume 82, 3427–3441, https://doi.org/10.1080/01418610208240453 (2002).

Donovan, P. Compressive deformation of amorphous Pd40Ni40P20. Materials Science and Engineering 98, 487–490 (1988).

Liu, C. T. et al. Test environments and mechanical properties of Zr-base bulk amorphous alloys. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 29, 1811–1820, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-998-0004-6 (1998).

Bruck, H. A., Christman, T., Rosakis, A. J. & Johnson, W. L. Quasi-static constitutive behavior of Zr41.25Ti13.75Ni10Cu12.5Be22.5 bulk amorphous alloys. Scripta Metallurgica et Materialia 30, 429–434, https://doi.org/10.1016/0956-716X(94)90598-3 (1994).

Hufnagel, T. C., Jiao, T., Li, Y., Xing, L. Q. & Ramesh, K. T. Deformation and Failure of Zr57Ti5Cu20Ni8Al10 Bulk Metallic Glass Under Quasi-static and Dynamic Compression. Journal of Materials Research 17, 1441–1445, https://doi.org/10.1557/JMR.2002.0214 (2002).

Chen, C., Gao, M., Wang, C., Wang, W.-H. & Wang, T.-C. Fracture behaviors under pure shear loading in bulk metallic glasses. Scientific Reports 6, 39522 (2016).

Wu, W. F., Li, Y. & Schuh, C. A. Strength, plasticity and brittleness of bulk metallic glasses under compression: statistical and geometric effects. Philosophical Magazine 88, 71–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/14786430701762619 (2008).

Yu, L. & Wang, T.-C. Fracture Behaviors of Bulk Metallic Glasses Under Complex Tensile Loading. Journal of Applied Mechanics 85, 011003-011003-011006, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4038286 (2017).

Yu, L. & Wang, T.-C. A new strain fracture criterion for bulk metallic glasses under complex compressive loading. International Journal of Solids and Structures (2018).

Jiang, Q. K. et al. La-based bulk metallic glasses with critical diameter up to 30mm. Acta Materialia 55, 4409–4418, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2007.04.021 (2007).

Choi-Yim, H. & Johnson, W. L. Bulk metallic glass matrix composites. Applied physics letters 71, 3808–3810 (1997).

Rudnicki, J. W. & Rice, J. R. Conditions for the localization of deformation in pressure-sensitive dilatant materials. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 23, 371–394, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(75)90001-0 (1975).

Qu, R. T., Eckert, J. & Zhang, Z. F. Tensile fracture criterion of metallic glass. Journal of Applied Physics 109, 083544, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3580285 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Nos 11702295, 11790292, 11602272, 11602270] and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences [Grant No. XDB22040503].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.C. Wang proposed the idea and outline of the research. L. Yu carried out the calculations. T.C. Wang and L. Yu conducted the theoretical analysis and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, L., Wang, TC. Generalized Mohr-Coulomb strain criterion for bulk metallic glasses under complex compressive loading. Sci Rep 9, 12554 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49085-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49085-1

This article is cited by

-

An Extension Strain Type Mohr–Coulomb Criterion

Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering (2021)

-

Generalized Mohr-Coulomb strain criterion for bulk metallic glasses under complex compressive loading

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.