Abstract

Interest in topological states of matter burgeoned over a decade ago with the theoretical prediction and experimental detection of topological insulators, especially in bulk three-dimensional insulators that can be tuned out of it by doping. Their superconducting counterpart, the fully-gapped three-dimensional time-reversal-invariant topological superconductors, have evaded discovery in bulk intrinsic superconductors so far. The recently discovered topological metal β-PdBi2 is a unique candidate for tunable bulk topological superconductivity because of its intrinsic superconductivity and spin-orbit-coupling. In this work, we provide experimental transport signatures consistent with fully-gapped 3D time-reversal-invariant topological superconductivity in K-doped β-PdBi2. In particular, we find signatures of odd-parity bulk superconductivity via upper-critical field and magnetization measurements— odd-parity pairing can be argued, given the band structure of β-PdBi2, to result in 3D topological superconductivity. In addition, Andreev spectroscopy reveals surface states protected by time-reversal symmetry which might be possible evidence of Majorana surface states (Majorana cone). Moreover, we find that the undoped bulk system is a trivial superconductor. Thus, we discover β-PdBi2 as a unique bulk material that, on doping, can potentially undergo an unprecedented topological quantum phase transition in the superconducting state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the traditional Landau-Ginzburg paradigm, states of matter are defined by the symmetries broken in thermal equilibrium that are preserved by the underlying Hamiltonian, and phase transitions acquire universal features that only depend on the symmetries involved and the spatial dimension. However, this definition proves inadequate for topological phases, in which the ground state wavefunction of the bulk system is characterized by a global, topological quantum number which distinguishes it from a conventional phase with the same symmetries1,2,3. Naturally, critical points separating these phases fall outside the traditional paradigm as well. The most striking consequence of the non-trivial bulk topology is the presence of robust surface states where the bulk terminates.

One of the most celebrated topological phases in condensed matter systems is the time-reversal symmetric strong topological insulator (TI) in three dimensions, which is characterized by a \({{\bf{Z}}}_{2}\) topological invariant ν = odd/even4,5. The surface manifestation of the bulk topology in this phase is the presence of an odd number of pseudo-relativistic, helical surface states (Dirac Cone) that are robust against non-magnetic perturbations. Numerous materials have been predicted to be in this phase, and many of them have been experimentally confirmed. Additionally, several TIs can be tuned into trivial insulators with doping, thus allowing experimental access to the quantum critical point separating them.

A close cousin of the topological insulator is the time-reversal symmetric topological superconductor (TSC) in 3D (Class 3D III)2. Here, the superconducting gap plays the role of the insulating gap of the insulator, the topological invariant is \(\nu \in {\bf{Z}}=\mathrm{0,}\,\mathrm{1,}\,2\ldots \), and the surface hosts ν helical Majorana fermions (Majorana cone) instead of Dirac fermions (Dirac Cone). The sufficient conditions for 3D time-reversal invariant (TRI) topological superconductivity are: One, the normal state Fermi surfaces enclose an odd number of time-reversal invariant momenta, two, the bulk superconductivity is fully gapped, and three, odd-parity6,7. Once these conditions are met, the surface states are spanned by robust, helical Majorana surface states. The 2D Majorana surface states also referred to as the Majorana cone (can be regarded as the superconducting analog of the 2D Dirac cone)— and is distinct from the Majorana Zero Mode (MZM). The transport signatures of 2D Majorana surface states are also distinct from that of MZM8,9. MZM has long been shown to exist in various 1D and 2D heterostructures of s-wave superconductors and spin-orbit coupled systems including topological insulators10,11, and in vortex core of some 2D topological metals12,13.

The main materials platform that has been studied experimentally for 3D/bulk topological superconductivity is the prototypical TI Bi2Se3 doped with Cu14,15,16. Unfortunately, undoped Bi2Se3 does not display superconductivity at ambient pressures, so a topological-to-trivial superconductor phase transition does not occur in this system. A unique bulk material candidate is the intrinsically superconducting topological metal, β-PdBi2— a layered, centrosymmetric, tetragonal compound. Spin-angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (spin-ARPES) and quasiparticle interference imaging have revealed the presence of spin-polarized topological surface states around Ef in the non-superconducting state17,18. Intrinsic spin-orbit-coupling (SOC) and superconductivity robust to different dopants, in addition to a relatively high Tc compared to other systems, make this material an attractive candidate for realizing tunable bulk topological superconductivity. β-PdBi2 already fulfills the first and second sufficient conditions, and can potentially fulfill the third condition. Although existing experiments show that the bulk superconductivity in pristine β-PdBi2 is s-wave19,20, because of intrinsic SOC, it can also be odd-parity. It is now well known that in the presence of SOC, electron-phonon interaction can give rise to even- as well as odd-parity superconductivity pairing21,22,23. Studies have shown that the s-wave, even-parity state invariably onsets at a higher Tc, driving the odd-parity state to T = 021. Suppressing the s-wave pairing channel can promote the odd-parity channel22,23.

In this work, we investigate the superconducting transport properties of β-PdBi2 tuned with K dopants. The main findings is that in layered, centrosymmetric topological metals (i.e with strong SOC), doping can be a tuning parameter between even- and odd-parity superconductivity. Since the parity of the bulk superconductivity is tied to the topological classification, doping can, therefore, drive a ‘trivial’ superconductor into a strong topological superconductor in these unique materials. Specifically in this report, we find signatures of unconventional bulk superconductivity in K-doped β-PdBi2: the upper-critical field exceeds the prediction by the Werthemer-Helfand-Hohenberg (WHH) orbital model for conventional s-wave pairing, but is consistent with the prediction for polar p-wave pairing. With odd-parity superconductivity in the bulk, helical Majorana fermions are expected to emerge as the 2D topological surface states. As the current ARPES systems do not have enough resolution to directly detect in-gap Majorana states, transport experiments via tunneling or Andreev spectroscopy is still the most direct experimental probe. Our point-contact spectroscopy (PCS) experiment in the Andreev spectroscopy regime shows signatures of helical surface states protected by time-reversal symmetry, consistent with the prediction for time-reversal-invariant 3D topological superconductors. Thus, K-doped β-PdBi2 is likely to be a 3D bulk topological superconductor and could undergo an unprecedented topological superconducting phase transition between a trivial (undoped) and a topological (doped) superconductor. If there is an intermediate magnetic phase, the TSC-magnetism critical point would be a condensed matter realization of supersymmetry24.

Bulk Superconducting Transport Properties

Magnetization: Normal state background

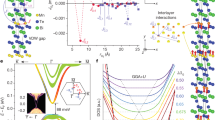

We begin by studying the basic normal state background from which the superconductivity arises in the pristine (onset Tc = 5.3 K) and potassium doped (0.3%) β-PdBi2 (Tc = 4.4 K). Above the superconducting transition temperature, evidence of topological Dirac surface states is found in the magnetoresistance via features of weak antilocalization25. In Fig. 1 we study the magnetization of the superconducting and normal state background. To observe the Meissner effect, we cooled the sample from room temperature down to 1.8 K and applied a small magnetic field ~2 Oe (Zero-Field Cooled, ZFC). The Meissner effect observed in the ZFC measurement on the K-doped sample is displayed in Fig. 1a. From this information, we derived the superconducting volume fraction, estimating that about 93% of the sample volume is superconducting. The magnetization vs magnetic field at 1.8 K displayed in Fig. 1b, shows that the parent (non-superconducting state) of the system is diamagnetic, as expected for topological insulators.

Basic transport properties of K-doped β-PdBi2. (a) Meissner effect in K-doped β-PdBi2. Zero-field-cooled (ZFC) data reveals bulk superconductivity onset at 4.4 K. (b) Magnetization as a function of applied magnetic field (M-B): plot suggests the upper critical field at 1.8 K is 0.68T. The inset shows that the non-superconducting state is diamagnetic. (c) Magnetization of K-doped β-PdBi2 in the non-superconducting state, showing a hump around 30 K. Such feature is characteristic of spontaneous spin ordering. (d) Theintrinsic magnetic susceptibility χ = M/B is calculated from the slope of the plots of isotherms of the magnetization vs magnetic field at several temperatures. The results reveal that the magnetic ordering arising close to low temperatures is intrinsic to the sample.

Shown in Fig. 1c is the temperature dependence of the zero-field-cooled magnetization of the doped sample. A magnetic field of 1T, higher than the upper-critical field, is applied along the c-axis. The sample is diamagnetic, except that at around 30 K, the magnetization displays an anomalous hump. Such a feature— concave hump in magnetization and susceptibility versus temperature— is characteristics of spontaneous spin ordering. To confirm that this hump is intrinsic to the sample26, we performed isothermal magnetization M(B) measurements. The intrinsic magnetic susceptibility χ is then extracted at different temperatures from the slope of the isotherms: M(B) ∝ χB. The hump in χ(T) is found to be intrinsic to the sample as shown in Fig. 1d. We discuss the possible origin of this feature in the discussion section. This magnetic excitation in the vicinity of superconductivity can suppress s-wave pairing in favor of spin-triplet paring.

Magnetization: vortex state

As a first check for the transport signature of the effect of the magnetic excitation in the vicinity of superconductivity, we study the vortex state. We recall that for Type 2 superconductors the vortex state— the intermediate state in which the superconducting state coexist with a ‘lattice’ of vortices created by penetrating magnetic field— is strengthened by doping. Doping creates defects which pin the vortices, increasing the irreversibility field Bhir and reducing the slope of magenetization curves beyond the lower-critical field Bc1. In the Fig. 2a, we illustrate the magnetization curves expected for superconductors; for Type 2 superconductors we emphasized the effects of the disorder. “Pure” type 2 superconductors refers to the limit of clean systems in elemental superconductors, while “Hard” superconductors refer to disordered superconductors. We expect K-doped β-PdBi2 to be relatively disordered compared to the pristine sample, thus exhibiting more of the “hard” Type 2 behaviour.

Vortex State. (a) Bc1 < B < Bc2 is the vortex state: flux vortices start to penetrate the superconductor at Bc1 and form a vortex lattice. Irreversibility of the magnetization loop is due to flux pinning effects. At the irreversibility field, the vortex lattice melts, restoring the reversibility. Doping increases the number of pinning sites and consequently, irreversibility. However, a spin-triplet superconductor does not follow this conventional behaviour; their vortex state is mostly ‘liquid’, resulting in poor flux pinning and reversibility. This behaviour is dubbed Type 1.527. (b–d) Comparison of the normalized magnetization along the B||c plane of both the undoped and doped sample, at 2.5 K and 1.8 K respectively. Beyond Bc1 of K-doped β-PdBi2 the magnetization shows an anomalous rate of increase in magnitude which is at odds with the conventional type-II “alloy” superconductors but consistent with the expectation for spin-triplet pairing.

In Fig. 2b, we compare the magnetization of the pristine crystal with the doped one. Below Bc1, labeled region I, diamagnetization occurs at the same rate for both systems; in region II, however, an anomalous behavior of the rate of magnetization is observed. The magnetization of doped sample behaves as if it is a cleaner sample in comparison with the pristine system!

The magnetization for a spin-triplet superconductor, as demonstrated for CuxBi2Se327, or in magnetic superconductors28 exhibits the so-called Type 1.5 like behavior (Fig. 2a). Consider the effect of the magnetic field induced by the persistent vortex current on the spins of the spin-triplet pairs. The induced magnetic field polarizes the Cooper pairs and an additional spin magnetization arises. The total magnetic flux in the vortex now consists of the current and spin magnetization contributions— and is quantized. The quantization of magnetic flux causes current inversion in parts of the vortex, favoring their formation just above Bc1 by driving an attractive interaction between the vortices. In the study by Das et al.27, the attractive interaction does not occur in s-wave superconductors. This explains the anomalous increase of the magnetization past the Bc1. Because the attractive interaction ‘melts’ the vortex lattice, low irreversibility is often observed in the magnetization vs magnetic field loop of CuxBi2Se315. This proposes that low irreversibility and anomalous magnetization in doped β-PdBi2, which is absent in the pristine sample, can also be explained by spin-triplet pairing.

Upper-critical field limiting effect

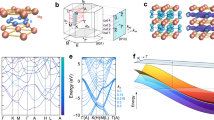

To investigate the transport properties of the bulk superconductivity in more details, we study the upper-critical field limiting effect. In Fig. 3, the upper-critical field Bc2 at different temperatures below Tc is plotted and extrapolated to T = 0 by using the form, Bc2(t) = Bc2(0)(1 − t2)/(1 + t2), where t = T/Tc. Bc2(0) is 0.69T for the pristine β-PdBi2 and a higher value of 0.89T is obtained for K-doped crystal in spite of it’s lower Tc. Backscattering by impurities, even non-magnetic ones, suppresses odd-parity superconductivity as Anderson theorem does not hold29,30. Thus, we first check if the mean free path l is greater than the coherent length ξc2. Using \({B}_{c2}={{\rm{\Phi }}}_{0}/2\pi {\xi }_{c2}^{2}\), where ξc2 is the Ginzburg-Landau coherence length and Φ0 is the flux quantum, we obtain ξ = 19 nm for K-doped β-PdBi2 and ξ = 21 nm for pristine β-PdBi2. Assuming a spherical Fermi surface for simplicity, we have wavenumber kF = (3π2n)1/3. Using n = 4.81 × 1027 m−3 derived from the linear part of ρxy (see25) for K-doped β-PdBi2 and the residual resitivity ρo from the longitudinal resistivity ρxx, the the mean free path \(l=\hslash {k}_{F}/{\rho }_{o}n{e}^{2}\) can be estimated. We find l = 75 nm. This l >> ξ combines contribution from both the surface and bulk state. If we use the only bulk carrier density, n = 3.4 × 1028 m−3 25, we have l = 22 nm, which is still greater than ξ = 19 nm. The doped crystal is sufficiently pure for odd-parity superconductivity. In contrast, we find that for the pristine sample, l = 8 nm < ξ.

Upper-critical field analysis. (a,b), Variation of the upper critical field Bc2 as a function of temperature in pristine and K-doped β-PdBi2. (c) The fit to Bc2(t) = Bc2(0)(1 − t2)/(1 + t2) is shown in red and blue for pristine and K-doped β-PdBi2 respectively. (d) Plot of the reduced upper critical field, b* = Bc2/|dBc2/dt|t=1 as a function of the reduced temperature t = T/Tc. The red dash is the upper-limit for s-wave superconductivity according to the WHH model. A conventional superconductor with finite SOC and Maki parameter will be below the universal WHH model curve. K-doped β-PdBi2 lies above the upper-limit of WHH model and closer to the polar p-wave model, pointing to K-doped β-PdBi2 as an odd-parity superconductor.

Under the BCS theory, superconductivity can be limited by the orbital and spin effect of an external magnetic field. The orbital depairing effect is described by the WHH theory while the spin limiting effect is described by the Pauli paramagnetism formalism by equating the paramagnetic polarization energy to the SC condensation energy \({\chi }_{n}{({B}_{c2}^{p})}^{2}=N\mathrm{[0]}{{\rm{\Delta }}}^{2}\), where N[0] is the density of state, Δ is the SC gap, and from which the polarization field, \({B}_{c2}^{p}\mathrm{(0)}\) = 1.86 Tc, is obtained. Under WHH theory in the clean limit, \({B}_{c2}^{orb}\mathrm{(0)}=0.72{T}_{c}|d{B}_{c2}/dT{|}_{{T}_{c}}\) = 0.75T for the doped sample. This is below the experimental Bc2 value, suggesting that superconductivity is not orbital-limited.

The spin limiting effect is described by the Pauli paramagnetism, \({B}_{c2}^{p}\mathrm{(0)}\) = 1.86 Tc = 8.184T, which is way above the experimental Bc2. So we have the relation: \({B}_{c2}^{orb}\mathrm{(0)}\, < \,{B}_{c2}\mathrm{(0)}\,\ll \,{B}_{c2}^{p}\mathrm{(0)}\), a relation which is also observed in CuxBi2Se316. Now, when both the orbital and Pauli limiting effects are present, then \({B}_{c2}={B}_{c2}^{orb}\mathrm{(0)}/\sqrt{1+{\alpha }^{2}}\) = 0.74T. α here is the Maki parameter31; α = \(\sqrt{2}{B}_{c2}^{orb}\mathrm{(0)/}{B}_{c2}^{p}\mathrm{(0)}\) = 0.13. The expected theoretical Bc2 in the presence of both the orbital and spin limiting effects is lower than the experimental value 0.89T. We can possibly conclude that the Pauli limiting effect is also absent.

We can gain more insight by comparing the Bc2(T) data with the well known theoretical model for s-wave32 and polar p-wave33. Figure 3d is the plot of the reduced upper critical field, b* = Bc2/|dBc2/dt|t=1 versus the reduced temperature t = T/Tc compared to the theoretical models for s-wave and polar p-wave SCs. For the doped crystal, we note that the experimental data exceeds the universal curve (upper-limit) for s-wave WHH model and fits better to the p-wave. The pristine β-PdBi2 in comparison lies below the upper-limit of the s-wave WHH theoretical prediction, as expected. It is important to note that WHH model presented in Fig. 3d is the universal curve (upper-limit), therefore the b* VS t experimental data for s-wave superconductors does not have to fit the WHH model, it only has to be below the limit. The universal curve (upper-limit) is derived for α = λso = 0, where α and λso are the Maki parameter31 and the spin-orbit strength, respectively. Non-zero α and λso moves experimental b* VS t curve below the theoretical universal curve. With non-zero α = \(\mathrm{0.53|}d{B}_{c2}/dT{|}_{{T}_{c}}\) = 0.11 and finite λso34 in β-PdBi2, the pristine crystal can be well described by the WHH model. This is in contrast to the doped crystal where b* lies above the s-wave WHH upper-limit.

These commonly available transport experiments reveal unconventional superconducting properties in doped β-PdBi2, which are a departure from the conventional BCS theory. More direct experimental methods, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for example35, will provide more direct evidence for spin-triplet superconductivity. Once the bulk of our system is topologically nontrivial, bulk-boundary correspondence demands the emergence of topologically protected surface states, which are 2D helical Majorana surface fluid for 3D TRI TSC7,8,36. In the next section, we study the surface states in the superconducting state using Andreev spectroscopy. We briefly note that 2D Majorana surface of a 3D TSC is distinct from the 0D MZM edge state derived from a 1D TSC or from the vortex core of 2D TSC and exhibits distinct transport properties8.

Surface Transport Properties

Andreev spectroscopy

We performed ‘soft’ point-contact spectroscopy37 (see Supplementary Information S1 and S2) on K-doped β-PdBi2 cooled down to 300 mK, studying the magnetic field and temperature dependence of the differential conductance, dI/dV. In point-contact spectroscopy, z is representative of the barrier strength: z = 0 is Andreev spectroscopy; while z = ∞ (z ~ 5 in experiments) is tunneling spectroscopy. Here z = 0.4. We present the magnetic field dependence of dI/dV with current along the ab plane and the magnetic field along the c axis in Fig. 4.

Point-contact spectroscopy. (a) Magnetic field dependence of the dI/dV vs bias voltage for K-doped β-PdBi2 at 0.3 K. (b,c) BTK fitting of the dI/dV spectrum at 0T for 0.3 K and 1.1 K. The fit is poor. In comparison, the fit is good at 0.1T in (d). (e) Field evolution of the quasi-particle lifetime broadening parameter Γ. (f) Close up view of dI/dV vs bias voltage at 0.7T and 0.8T. (g) Attempts to fit the gap with the BCS magnetic field dependence equation.

We note that the spectrum at zero magnetic field is unconventional and looks remarkably different from the rest. In particular, in Fig. 4a (where we have normalized dI/dV to 1 as V → ∞), we see conductance dips at ±1 meV and conductance peaks exceeding the value predicted by the Blonder-Tinkham-Klapwijk (BTK) formalism of Andreev reflection38 for a conventional SC-insulator-normal metal interface (with z = 0.4). In fact, the peaks at 0.3 K exceed the theoretical maximum value of 2 (required by the Andreev process) for a gapped superconductor— indicative of the absence of conventional Andreev process— and thus might be a signature of the presence gapless surface states spanning the topological bulk gap.

To rule out trivial effects, let us recall the known causes of conductance dip in PCS dI/dV spectra. (i) Critical current or heating effect— dips at positions larger than the superconducting energy gap are often found in the spectrum when the contacts on the sample are in the thermal limit39. At the superconducting critical current, the superconductor turns into a normal metal, and when measurements are carried out in the thermal limit, the resistance of the bulk sample is measured in the dI/dV spectrum. Since the critical current required to limit superconductivity reduces with increasing magnetic field and temperature, these dips are found to occur at positions of decreasing lower bias voltage. In our experiments, the dip position does not reduce with increase in temperature and magnetic field (in fact it was only observed at zero magnetic field), so the critical current effect is ruled out (See Supplementary Information S2). (ii) 1D, 2D and 3D TSC — topological superconductors feature dips at ±Δ. A simple physical explanation for this is the transfer of spectra weight from the states near the gap to make up for the in-gap states. In addition to the dips, 1D and 2D TSCs feature zero-bias conductance peak (ZBCP) due to Andreev bound state (ABS), while 3D TRI TSCs do not8,10,14,40,41.

For a finite potential barrier between the contact and an ideal 3D topological superconductor, dI/dV ∝ surface density of states, and differential conductance spectrum should produce a double peak structure8,14,41 — that is, ZBCP is not expected for fully gapped 3D TRI topological superconductors. It should be pointing out, however, that the tunneling conductance can feature a ZBCP due to various effects. In studies for superconducting 3D TI, remnant Dirac fermions from the normal state are found to modify in the superconducting state in two ways: one, it enhances the pair potential resulting in a larger gap for the surface superconductivity42. Two, if the Dirac surface states are well separated from the bulk, it can twist the surface Majorana cone, resulting in the ZBCP41. Furthermore, if the bulk superconductivity is not fully-gapped as is the case for CuxBi2Se3, for example, the tunneling conductance features a ZBCP14. Otherwise, in the ideal case, the differential conductance features a double peak.

Although the exact surface conductance spectrum of topological β-PdBi2, which will take into account the peculiar microscopics of the odd-parity bulk pairing allowed by the irreducible representations of its tetragonal C4 symmetry, has not been theoretically calculated yet; here, the presence of unconventional double conductance peak and nontrivial conductance dips at zero magnetic field are in good agreement with the general theoretical prediction for spin-triplet p-wave pairing for Balian-Werthamer (BW) phase of superfluid He-3 (see Fig. 4 in Yamakage et al.41). 3D TRI TSCs are the electronic analogue of He-3 BW phase. Alternately, we also consider the possibility that the unconventional surface conductance spectrum is a signature of surface helical superconductivity resulting from the Cooper pairing of the singly spin degenerate surface states present in the normal state. Such surface helical superconductivity are not s-waves but p-waves in nature and are considered as 2D topological superconductivity. This will be an intrinsic version of the surface helical superconductivity induced in heterostructures of s-wave superconductor and topological insulators43

Looking beyond the presence of unconventional surface states, we study its response to a time-reversal breaking perturbation, that is, a magnetic field. Analogous to the time-reversed Dirac fermions on the surface of a TI which are protected from backscattering, the superconducting state is expected host helical pairs of Majorana fermions which are robust against non-magnetic disturbances36,43. This physics is captured here: applying a magnetic field breaks time-reversal symmetry— and protection from scattering is lifted. The helical surface states are localized, the surface states are gapped, and the underlying gapped superconductivity described by the usual BTK-like spectrum is uncovered. We see in Fig. 4b–d that the spectrum under 0.1T at 0.3 K fits the BTK model for conventional superconductivity38,44 while that under zero magnetic field does not.

Next, we extracted the superconducting gap by fitting the experimental data at different magnetic fields to the BTK equation and attempted to fit its evolution with the prediction for a conventional Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) superconductor: Δ(B) = Δ0(1 − B/Bc2)1/2. Experimentally, Bc2 is found to be somewhere between 0.7 and 0.8T according to the B field dependence of Andreev reflection as shown in Fig. 4f. However, the gap could not be described by BCS using 0.7T < Bc2 < 0.8T; the misfit for 0.8T is shown in 4g. By making both the Δ0 and Bc2 free parameters, we got the best fit with 0.63T. Clearly, as shown in Fig. 4f the crystal is still superconducting up till at least 0.7T. This proposes that the superconducting state might not be entirely described by conventional BCS theory.

Discussion

In this paper, we have shown that in K-doped β-PdBi2 the bulk superconductivity is unconventional— a necessary condition for 3D topological superconductivity, and that the surface states are helical, a signature of this phase. We now address the question of why the doped system behaves so differently than the undoped one. We recall that sufficient conditions for topological superconductivity in a 3D TRI material are that the normal state Fermi surfaces enclose an odd number of TRIM and the fully-gapped bulk superconductivity pairing be odd under inversion. In pristine β-PdBi2 only the former condition met. Bulk superconductivity is s-wave19,20,45, so bulk topological superconductivity is not expected; instead, in a 2D thin-film one might get a Fu-Kane-like superconductor with edge Majorana zero modes in vortex cores11,13 (see lower-left corner of Fig. 5b), which are distinct from 2D helical Majorana surface states (lower-right corner of Fig. 5b).

3D topological superconducting phase transition. (a) Centrosymmetric, layered materials can possess hidden spin-polarization in the bulk46; ‘hidden’ because the net spin-polarization cancels each other out. Naturally, the surfaces are spin-polarized, as is the case for pristine β-PdBi2 which possess trivial spin-polarized surface-states in addition to the topological surface-states. We proposed here that a net spin-polarization in the bulk can arise due to the doping effect which breaks the local inversion symmetry at random, intermittent sites. (b) Upper-left: topological metal: Fermi level Ef is placed above (or below) the topological surface states (SS). Upper-right: Doping depletes the bulk bands, exposing the SS. Lower-left: even-parity superconductivity in the bulk of a topological metal gaps out the bulk states and the Dirac SS; the superconductivity induced in the singly degenerate surface states resulting in a surface helical superconductivity, which is a 2D topological superconductor. In thin-films or cleaved materials, Majorana zero mode (MZM) (also referred to as Majorana bound state) can be trapped at the ends of the vortex cores. Lower-right: odd-parity bulk superconducting paring turns the bulk system into a 3D topological superconductor, which hosts in-gap, helical Majorana fermion surface states. This is the subject of this paper. While signatures of Majorana zero mode (MZM) have been demonstrated in several experiments, the 2D Majorana surface states unique to 3D TSC has been elusive. We propose that inducing a net spin-polarization in the bulk of centrosymmetric, layered topological metals can be a route to tunable 3D/bulk topological superconductivity in these materials.

Appropriate dopants can introduce Coulomb interaction, and in a layered centrosymmetric material, spin polarization46,47. Introducing either of these in a superconducting topological metal (which can host both s-wave and odd-parity because of intrinsic SOC), will suppress the s-wave pairing channel in favor of an odd-parity channel21,22,23. Here, on doping with K, we find that the c-lattice parameter increases25, indicating that the K + ions have replaced the smaller ions in β-PdBi2. This would lead to local inversion symmetry breaking without breaking the centrosymmetry of the bulk crystal, which is enough to unveil the hidden spin polarizations in the bulk of layered, centrosymmetric systems46,47. See Fig. 5a.

In the centrosymmetric Bi2Se3, superconductivity is induced by intercalating A = Cu, Nb, Sr into the non-superconducting parent compound. Recent transport studies on AxBi2Se3 have shown the evidence of 2-fold pairing symmetry consistent with odd-parity, nematic superconductivity as opposed to the 6-fold symmetry of the hexagonal Bi2Se3 structure35,48,49,50. However, undoped Bi2Se3 does not display superconductivity at ambient pressures, so a topological-to-trivial superconductor phase transition does not occur in this system. The fully-gapped bulk superconductivity intrinsic to β-PdBi2 opens the possibility of an unprecedented topological phase transition in the superconducting state from a trivial to a topological superconductor. In case the topological superconductor first transitions into a magnetic phase, the accompanying critical point will present a unique and robust laboratory realization of emergent supersymmetry24.

In conclusion, we have presented the transport evidence for an intrinsic time-reversal-invariant topological superconductor in three dimensions. In the superconducting state, transport experiments give evidence that there is a different superconducting mechanism involved in the K-doped system compared to the pristine system. The upper-critical field experiments on K-doped β-PdBi2, in contrast to the pristine β-PdBi2, shows that the superconductivity exceeds WHH upper-limit for s-wave superconductivity; a signature of spin-triplet superconductivity. This is the sufficient condition for bulk topological superconductivity given that the normal state Fermi surface of β-PdBi2 encloses an odd number of single time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM). Furthermore, Andreev spectroscopy reveals an unconventional spectrum at zero magnetic field, which possibly reflects the helical nature of 2D Majorana surface fluid, a surface manifestation of the non-trivial topology of the bulk. Different experimental approaches, in addition to material-specific theoretical studies, are required to determine the microscopics of the superconductivity. The coexistence of intrinsic superconductivity, topologically non-trivial bulk bands, and topological surface states in β-PdBi2 presents a unique material platform to study the interplay of Dirac fermions and Majorana fermions quasiparticles in condensed matter settings.

Experimental Methods

Transport measurements

The four-probe technique was used for the longitudinal resistance, Rxx, and the Hall resistance, Rxy, was acquired by the standard method. The magneto-resistance and magnetization measurements were carried out using Quantum Design Inc.’s Physical Properties Measurement System (PPMS. The magnetic properties of the samples were characterized using Quantum Design Inc.’s Magnetic Property Measurement System (MPMS). The device is able to detect small signals (≤10−8 emu) with great accuracy using the superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometry technology. The MPMS can access temperatures as low as 1.8 K and can ramp the magnetic field up to 7T. The ‘soft’ point-contact spectroscopy was performed in an He-3 refrigerator. The current is past through a thin Au wire to the sample through a 30 μm tiny drop of Ag nano-particle epoxy paint. To acquire the dI/dV data, a small AC current is superimposed with a sweeping DC current.

References

Moore, J. E. The birth of topological insulators. Nature 464, 194 (2010).

Schnyder, A. P., Ryu, S., Furusaki, A. & Ludwig, A. W. Classification of topological insulators and superconductors in three spatial dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 78, 195125 (2008).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045 (2010).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Topological insulators with inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 76, 045302 (2007).

Chen, Y. et al. Experimental realization of a three-dimensional topological insulator, Bi2Te3. Science 325, 178–181 (2009).

Sato, M. Topological properties of spin-triplet superconductors and Fermi surface topology in the normal state. Phys. Rev. B 79, 214526 (2009).

Fu, L. & Berg, E. Odd-parity topological superconductors: theory and application to CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 097001 (2010).

Sato, M. & Ando, Y. Topological superconductors: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys 80, 076501 (2017).

Xie, H.-Y., Chou, Y.-Z. & Foster, M. S. Surface transport coefficients for threedimensional topological superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 91, 024203 (2015).

Mourik, V. et al. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductorsemiconductor nanowire devices. Science 336, 1003–1007 (2012).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Yin, J. et al. Observation of a robust zero-energy bound state in iron-based superconductor Fe (Te, Se). Nat. Phys. 11, 543 (2015).

Lv, Y.-F. et al. Experimental signature of topological superconductivity and Majorana zero modes on β-Bi2Pd thin films. Sci. Bull. 62, 852 (2017).

Sasaki, S. et al. Topological superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 217001 (2011).

Kriener, M., Segawa, K., Ren, Z., Sasaki, S. & Ando, Y. Bulk superconducting phase with a full energy gap in the doped topological insulator CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 127004 (2011).

Bay, T. et al. Superconductivity in the doped topological insulator CuxBi2Se3 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 057001 (2012).

Sakano, M. et al. Topologically protected surface states in a centrosymmetric superconductor β-PdBi2. Nat. Commun. 6, 8595 (2015).

Iwaya, K. et al. Full-gap superconductivity in spin-polarised surface states of topological semimetal β-PdBi2. Nat. Commun. 8, 976 (2017).

Kacmarcik, J. et al. Single-gap superconductivity in β-Bi2Pd. Phys. Rev. B 93, 144502 (2016).

Herrera, E. et al. Magnetic field dependence of the density of states in the multiband superconductor β-Bi2Pd. Phys. Rev. B 92, 054507 (2015).

Brydon, P., Sarma, S. D., Hui, H.-Y. & Sau, J. D. Odd-parity superconductivity from phonon-mediated pairing: application to CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. B 90, 184512 (2014).

Kozii, V. & Fu, L. Odd-parity superconductivity in the vicinity of inversion symmetry breaking in spin-orbit-coupled systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 207002 (2015).

Wang, Y., Cho, G. Y., Hughes, T. L. & Fradkin, E. Topological superconducting phases from inversion symmetry breaking order in spin-orbit-coupled systems. Phys. Rev. B 93, 134512 (2016).

Grover, T., Sheng, D. & Vishwanath, A. Emergent space-time supersymmetry at the boundary of a topological phase. Science 344, 280–283 (2014).

Kolapo, A., Hosur, P. & Miller, J. Non-linear Hall effect, high mobility, and weak antilocalization due to topological surface states in doped β-PdBi2. Submitted simultaneous to same journal (2019).

Anand, V., Kim, H., Tanatar, M., Prozorov, R. & Johnston, D. Superconducting and normal-state properties of APd2As2 (A = Ca, Sr, Ba) single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 87, 224510 (2013).

Das, P., Suzuki, Y., Tachiki, M. & Kadowaki, K. Spin-triplet vortex state in the topological superconductor CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. B 83, 220513 (2011).

Tachiki, M., Matsumoto, H. & Umezawa, H. Mixed state in magnetic superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 20, 1915 (1979).

Fay, D. & Appel, J. Coexistence of p-state superconductivity and itinerant ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. B 22, 3173 (1980).

Foulkes, I. F. & Gyorffy, B. p-wave pairing in metals. Phys. Rev. B 15, 1395 (1977).

Maki, K. Effect of Pauli paramagnetism on magnetic properties of high-field superconductors. Phys. Rev. 148, 362 (1966).

Werthamer, N., Helfand, E. & Hohenberg, P. Temperature and purity dependence of the superconducting critical field, Hc2. III. Electron spin and spin-orbit effects. Phys. Rev. 147, 295 (1966).

Scharnberg, K. & Klemm, R. p-wave superconductors in magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 22, 5233 (1980).

Shein, I. R. & Ivanovskii, A. L. Electronic band structure and Fermi surface of tetragonal low-temperature superconductor Bi2Pd as predicted from first principles. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 26, 1–4 (2013).

Matano, K., Kriener, M., Segawa, K., Ando, Y. & Zheng, G.-Q. Spin-rotation symmetry breaking in the superconducting state of CuxBi2Se3. Nat. Phys. 12, 852 (2016).

Qi, X.-L., Hughes, T., Raghu, S. & Zhang, S.-C. Time-reversal-invariant topological superconductors and superfluids in two and three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 187001 (2009).

Daghero, D. & Gonnelli, R. Probing multiband superconductivity by pointcontact spectroscopy. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 23, 043001 (2010).

Blonder, G. E., Tinkham, M. & Klapwijk, T. M. Transition from metallic to tunneling regimes in superconducting microconstrictions: Excess current, charge imbalance, and supercurrent conversion. Phys. Rev. B 25, 4515 (1982).

Sheet, G., Mukhopadhyay, S. & Raychaudhuri, P. Role of critical current on the point-contact Andreev reflection spectra between a normal metal and a superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 69, 134507 (2004).

Kashiwaya, S., Kashiwaya, H., Saitoh, K., Mawatari, Y. & Tanaka, Y. Tunneling spectroscopy of topological superconductors. Physica, E, Low-dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 55, 25–29 (2014).

Yamakage, A., Yada, K., Sato, M. & Tanaka, Y. Theory of tunneling conductance and surface-state transition in superconducting topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 85, 180509 (2012).

Mizushima, T., Yamakage, A., Sato, M. & Tanaka, Y. Dirac-fermion-induced parity mixing in superconducting topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 90, 184516 (2014).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Momentum space imaging of Cooper pairing in a half-Dirac-gas topological superconductor. Nat. Phys. 10, 943–950 (2014).

Dynes, R. C., Narayanamurti, V. & Garno, J. P. Direct measurement of quasiparticlelifetime broadening in a strong-coupled superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 41, 1509 (1978).

Che, L. et al. Absence of Andreev bound states in β-PdBi2 probed by pointcontact Andreev reflection spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 94, 024519 (2016).

Zhang, X., Liu, Q., Luo, J.-W., Freeman, A. J. & Zunger, A. Hidden spin polarization in inversion-symmetric bulk crystals. Nat. Phys. 10, 387 (2014).

Riley, J. M. et al. Direct observation of spin-polarized bulk bands in an inversionsymmetric semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 10, 835 (2014).

Yonezawa, S. et al. Thermodynamic evidence for nematic superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3. Nat. Phys. 13, 123–126 (2017).

Pan, Y. et al. Rotational symmetry breaking in the topological superconductor SrxBi2Se3 probed by upper-critical field experiments. Sci. Rep. 6, 28632 (2016).

Asaba, T. et al. Rotational Symmetry Breaking in a Trigonal Superconductor Nb-doped Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. X 7, 011009 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge R. Forrest, K. Dahal, Y. Lyu, S. Huyan and U. Saparamadu for technical assistance. We thank Prof. W.-P. Su, Prof. C. Ting, and Prof. R. Du for helpful discussions. The work in Houston is supported in part by the State of Texas through the Texas Center for Superconductivity at University of Houston (A.K. and J.H.M.); and the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research Grant No. FA9550-15-1-0236, and the T.L.L. Temple Foundation, the John J. and Rebecca Moores Endowment (A.K.); and by the Division of Research, Department of Physics and the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics at the University of Houston (P.H.). T.L. is supported by NSF grant number DMR-1508644.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. conceived the idea for the project, A.K. and T.L. performed the experiments, A.K., P.H. and J.H.M. interpreted the results, A.K. and P.H. wrote the paper, and J.H.M. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41598_2019_48906_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS: Possible transport evidence for three-dimensional topological superconductivity in doped β-PdBi<Subscript>2</Subscript>

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolapo, A., Li, T., Hosur, P. et al. Possible transport evidence for three-dimensional topological superconductivity in doped β-PdBi2. Sci Rep 9, 12504 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48906-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48906-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.