Abstract

Deficiency of propionyl-CoA carboxylase causes propionic acidemia and deficiencies of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase or its cofactor adenosylcobalamin cause methylmalonic acidemia. These inherited disorders lead to pathological accumulation of propionyl-CoA which is converted in Krebs cycle to methylcitrate (MCA) in a reaction catalyzed by citrate synthase. In healthy individuals where no propionyl-CoA accumulation occurs, this enzyme drives the condensation of acetyl-CoA with oxaloacetate to produce citric acid (CA), a normal Krebs cycle intermediate. The competitive synthesis of CA and MCA through the same enzymatic mechanism implies that increase in MCA production is accompanied by decrease in CA levels. In this study, we assessed MCA concentration and the ratio of MCA/CA as plausible markers for propionic and methylmalonic acidemias. We measured MCA and CA in dried blood spots using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. The reference ranges of MCA, CA and MCA/CA in 123 healthy individuals were ≤0.63 µmol/L, 36.6–126.4 µmol/L and 0.0019–0.0074, respectively. In patients with propionic and methylmalnic acidemias (n = 7), MCA concentration ranged between 1.0–12.0 µmol/L whereas MCA/CA was between 0.012–0.279. This is the first report to describe the potential role of MCA and MCA/CA in dried blood spots as diagnostic and monitoring biomarkers for inherited disorders of propionyl-CoA metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Propionic acidemia (PA) and methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) are inborn errors of propionyl-CoA metabolism caused by defects in enzymes required for correct catabolism of branched-chain amino acids, odd chain fatty acids and cholesterol1. Mutations in genes encoding propionyl-CoA carboxylase, a biotin-requiring enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of propionyl-CoA to methylmalonyl-CoA cause PA2,3. MMA is a more etiologically heterogeneous disorder that can present as isolated MMA or in combination with homocystinuria. The former is caused by genetic defects in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase or its cofactor adenosylcobalamin. Combined MMA and homocystinuria is due to genetic anomalies affecting adenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin, the two biologically active forms of vitamin B12. Other less common causes of MMA have also been reported1,4,5.

Patients with PA and MMA typically present in the neonatal period with high anion gap metabolic acidosis, ketosis, and hyperammonemia. Severe life-threatening complications including progressive neurological dysfunction or early death are common6,7,8. Early diagnosis is critical as presymptomatic treatment is associated with better outcomes9,10. The biochemical hallmarks of PA include accumulation of glycine, propionylcarnitine, propionylglycine, 3-hydroxypropionic acid, and methylcitrate (MCA). In MMA, accumulation of methylmalonic acid together with elevated glycine, propionylcarnitine, 3-hydroxypropionic acid and MCA is diagnostic1,3,11.

Management of PA and MMA aims at reducing toxic metabolites and maintaining normal growth and development. Protein restriction, optimal calorie intake, carnitine supplementation and suppressing microbial propionate production represent the treatment mainstay. Some MMA patients are vitamin B12 responsive and benefit from hydroxycobalamin treatment. Monitoring methylmalonic acid levels in these patients is an essential part of the management plan. Regrettably, a suitable biochemical marker to monitor PA patients is currently lacking.

Recently we developed methods for the analysis of MCA in dried blood spot (DBS) and dried urine spot samples and showed that this marker improves newborn screening for disorders of propionate metabolism12,13,14. MCA and its physiological counterpart, citric acid (CA) are produced in Krebs cycle in a reaction catalyzed by the same enzyme, namely citrate synthase15,16. In this work, we used liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to simultaneously determine CA and MCA in DBS in the same analytical run. This allowed for the calculation of MCA/CA ratio, a novel biomarker that may potentially apply for all disorders of propionate metabolism. The diagnostic and monitoring potential of these biomarkers was evaluated using specimens collected from controls and patients with established diagnosis of PA and MMA.

Results

Sample analysis

Optimum derivatization conditions for CA and its deuterium labeled internal standard (d4-CA) with 4-[2-(N,N-dimethylamino)ethylaminosulfonyl]-7-(2-aminoethylamino) -2,1,3-benzoxadiazole (DAABD-AE) were similar to those previously reported12,14,17,18. Infusion of the derivatization reaction mixture into the first quadrupole revealed intense ions at mass to charge ratio (m/z) of 485 and 489 corresponding to DAABD-AE derivatives of CA and d4-CA. Collision induced dissociation and subsequent scanning by the second resolving quadrupole revealed m/z 151 as an intense and common fragment to both CA and d4-CA. These results are in agreement with the fragmentation pattern obtained with MCA and its deuterium labeled analogue d3-MCA12. Chromatographic conditions were optimized so that CA and MCA derivatives are eluted away from other substances with potential ion suppression effect. CA and MCA eluted at 3.6 and 3.7 min, respectively. Surging the organic content to 95% was required to wash out late eluting compounds from the column. After each sample, the column was re-equilibrated for 2 min giving an injection-to-injection time of 8 min. Figure 1 shows extracted mass chromatograms obtained with a DBS sample from a healthy individual (Fig. 1A–D), and a DBS sample from a patient with MMA (Fig. 1E–H).

Assay performance

Linear relationships between the area ratios of analyte to internal standard versus concentration in DBS were established by spiking blood in the range of 2.5–200 µmol/L for CA and 0.25–16 µmol/L for MCA. Given that endogenous CA was at 92.8 µmol/L, the overall linearity range (endogenous + spiked) was up to 292.8 µmol/L. For MCA, the endogenous concentration was 0.23 µmol/L, therefore and the overall linearity range (endogenous + spiked) was up to 16.23 µ µmol/L. Linear regression equations for CA and MCA of y = 0.0065x-0.0041 (r = 0.995) and y = 0.0046x + 0.0009 (r = 0.997), respectively, were obtained with y as peak area ratio, x as the added analyte concentration (µmol/L) and r as the correlation coefficient.

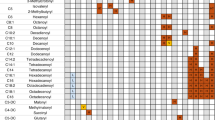

Accuracy, intraday (n = 12) and interday (n = 12) imprecisions of CA and MCA in spiked DBS specimens are shown in Table 1. The analytical recovery calculated from these measurements ranged between 98–105% for MCA and 95–110% for CA.

Analysis of controls and patients’ samples

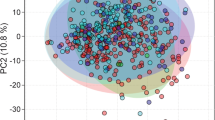

Table 2 shows the median, range and 95% reference ranges of CA, MCA and MCA/CA ratio in DBS from controls (n = 123) and patients (n = 7) with confirmed inborn error of propionate metabolism. Figure 2 shows the distribution of MCA and the ratio of MCA/CA in the study population. Figure 3 shows the results of MCA and MCA/CA measured in consecutive DBS samples collected daily from two MMA patients before and after starting IM hydroxycobalamin (1.0 mg/day). Shown for comparison purpose, methylmalonic acid was also analyzed according to known methods19.

Methylmalonic acid (A), MCA (B) and MCA/CA (C) in daily consecutive DBS samples (n = 11) collected from a vitamin B12 responsive MMA patient before and after starting treatment with IM hydroxycobalamin (1.0 mg/day). Methylmalonic acid (D), MCA (E) and MCA/CA (F) in daily consecutive DBS samples (n = 34) collected from a vitamin B12 non-responsive MMA patient before and after starting treatment with IM hydroxycobalamin (1.0 mg/day).

Discussion

Propionylcarnitine, a diagnostic biomarker common to both PA and MMA, is not recommended as follow up marker to guide clinical patient management6. While ammonia, blood gases and calculated anion gap are non-specific markers that also occur in other disorders1,3,6, a number of complications occur in PA and MMA patients despite these biomarkers being within therapeutic targets. Measuring methylmalonic acid, unique to MMA, provides important clues on response to treatment, vitamin B12 responsiveness and compliance20. On the other hand, the challenge in managing PA patients is confounded by the lack of a reliable biomarker for monitoring and prognostication.

Formed as a consequence of propionyl CoA accumulation, MCA is a characteristic abnormal metabolite that is common to all inborn errors of propionyl-CoA metabolism including PA and MMA. Citrate synthase, the enzyme catalyzing the physiological production of CA in Krebs cycle is responsible of forming MCA as a result of condensation of the pathologically accumulating propionyl CoA with oxaloacetate15,16. Elevated MCA and deficient CA are implicated in the pathogenesis of MMA and PA. Brain cell cultures derived from wild type mouse embryos challenged with MCA showed alterations of the developing brain morphology, increased ammonium concentrations and apoptotic cell death21,22. Given the role of propionate metabolism in anaplerosis of the citric acid cycle through provision of succinyl-CoA and sequestration of oxaloacetate by propionyl-CoA, severe deficiency of citric acid cycle intermediates is anticipated in patients with defects of propionate metabolism3. A biomarker that takes these observations into account, should arguably be more clinically useful.

In a previous work, we reported a novel method for the analysis of MCA in neonatal DBS specimens using LC-MS/MS, a technology commonly available in clinical laboratories12,13. In the current work, we extended our method to include the simultaneous analysis of CA, the structural and biological counterpart of MCA with implications for the management of patients with PA and MMA23. Given the physicochemical similarities of these tricarboxylic acids, CA was also derivatized with DAABD- AE using the conditions established earlier for MCA12,14. The sample preparation was minimal and consisted of a single step encompassing both extraction and derivatization. The resultant DAABD derivatives of CA and MCA were well resolved by reversed phase chromatography in less than 4 min (Fig. 1). The reference range of CA in DBS obtained in this work of 36.6–126.4 µmol/L was comparable to that previously reported in plasma of 128.2 ± 31.1µmol/L24. In DBS samples from patients with inborn error of propionate metabolism, CA that ranged from 26.2–89.1 µmol/L was significantly lower than controls (p < 0.01). Our assay was adequately reproducible with CV (%) measured at various concentrations of ≤15.1% (Table 1). The use of deuterium labelled analogues as internal standards improved the overall performance of this assay.

The study presented here is the first to evaluate the potential of MCA and its ratio to CA as monitoring markers of disorders of propionate metabolism. The competitive synthesis of CA and MCA through the same enzymatic mechanism implies that the increase in MCA production is accompanied by a decrease in CA levels. Therefore, this inverse relation disrupts the resultant MCA/CA ratio and may serve as an important indictor to assess the disease course and/or severity. As a proof of concept, we assessed MCA and MCA/CA as monitoring biomarkers in consecutive DBS samples from two MMA patients, one known to be vitamin B12 responsive and the other is vitamin B12 non-responsive. We compared our results with methylmalonic acid, the routinely used follow up marker (Fig. 3). The vitamin B12 responsive patient was initially admitted due to metabolic decompensation caused by non-compliance with the prescribed therapy. As part of the intervention, the patient received daily IM hydroxycobalamin (1.0 mg). DBS samples were collected at admission and daily thereafter for a total of 11 days. As shown in Fig. 3A–C, MCA and MCA/CA ratio, adequately predicted the response to treatment in the first five days as well as the metabolic derangement and consequent accumulation of MCA which was triggered by a nosocomial infection (day 6 and 7). This pattern was in agreement with that obtained with methylmalonic acid. In the patient who is non-responsive to vitamin B12 treatment (Fig. 3D–F), methylmalonic acid, MCA and MCA/CA ratio remained elevated despite the daily administration of hydroxycobalamin (1.0 mg IM). One may argue that MCA and MCA/CA are potentially superior to MMA as routine biomarkers due to the simple sample preparation required and universal applicability to all inborn errors of propionate metabolism including PA.

Although MCA alone seems adequate to discriminate patients from controls as shown in Fig. 2, the MCA/CA ratio proposed in this work might be superior as it can be conveniently calculated using instrument readout without the need for demanding calibration curve procedures. Further, measuring both analytes in the same run improves the analytical process and compensates for instrumental or sample preparation variations. We also believe that the use of MCA/CA ratio that depends on two competitively-synthesized and inversely-related markers may allow for improved ascertainment of patients with milder disease variants associated with subtle MCA elevations.

Nevertheless, to establish these markers in DBS as predictors of disease course and/or therapeutic outcomes, additional studies are required to assess their clinical validity and utility using larger sample size from patients with other relevant disorders, and across different pathophysiological circumstances.

In conclusion, this is the first report on the use of MCA and its ratio to CA as novel markers with potential diagnostic and monitoring roles in patients of inherited disorders of propionyl-CoA metabolism. Stratification of MCA levels using CA as denominator provides valuable clues on PA and MMA as these inversely related metabolites are competitively synthesized by the same enzyme system. The combined use of MCA concentration and the ratio of MCA stratified with CA significantly improved the specificity of our method while maintaining 100% sensitivity. The performance of MCA and its ratio to CA as follow up markers for our MMA patients was comparable to that of the routinely used methylmalonic acid. These novel biomarkers could prove more versatile as they can be used also in PA patients. After validation with more patients’ samples, our simple and robust approach can be efficiently included as part of care of patients with inherited propionyl-CoA metabolic defects.

Methods

Chemicals

Cambridge Isotopes Laboratories (Tewksbury, Massachusetts, USA) was the source of MCA, d3-MCA and d4-CA. Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) supplied us with water, acetonitrile and methanol (LC-MS/MS grade). The following chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany): CA, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), 4-(dimethylamino) pyridine (DMAP), DAABD-AE and N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC). Stock solutions of CA, MCA and the deuterium labeled internal standards were prepared in acetonitrile:water (1:1, v/v) at 1.0 mg/mL and diluted to the desired concentrations using the same solvent. These solutions were protected from light and stored at −20 °C for 6 months as previously described14.

Study samples

Al Ain Medical District Human Research Ethics Committee granted approval for this study (ERH-2017–5494 17-01). All experiments were carried out according to applicable rules and regulations. Participants, parents or legal guardians provided informed consent for study participation. For the determination of reference ranges, DBS samples from control subjects (n = 123) were analyzed. DBS samples (n = 50) from seven confirmed patients with MMA (n = 3) and PA (n = 4) were also studied. Of these fifty, consecutive daily DBS specimens before and after starting hydroxycobalamin treatment (1.0 mg/day intramuscular injection, IM) were collected from MMA patient-1 (n = 11) and MMA patient-2 (n = 34). DBS specimens were prepared by spotting 70 µL of blood on Whatman 903 filter paper cards using an Eppendorf pipette. These specimens were dried at ambient temperature for at least 4 hours and placed in sealed plastic bags with desiccant at 4 °C until analysis.

Sample pretreatment

CA and MCA were measured in DBS samples as derivatives of DAABD-AE using a modified version of our previously described method12. In brief, a 3.2 mm circle was excised from the DBS specimen, placed in an Eppendorf Snap-Cap microcentrifuge tube (1.5 mL) and incubated for 45 min at 65 °C with the following: 20 µL of d3-MCA and d4-CA (24 µmol/L in 50% acetonitrile) and 100 µL of a mixture of 25 mmol/L EDC in water, 2 mmol/L DAABD-AE in 90% acetonitrile, and 25 mmol/L DMAP in acetonitrile (1:2:1,v/v/v) as we previously described14. After adding 900 μL of methanol:water (1:9, v/v) containing 0.5 g/L of PFOA to stop the reaction, 2 µL of the mixture were injected into the LC-MS/MS system.

LC-MS/MS analysis

In this work, we used our previously described14 LC-MS/MS system which consists of a Nexera X2 UHPLC interfaced with an LC-MS 8060 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ion source (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Chromatography was accomplished using an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 µm, Waters, Milford, USA) maintained at 40 °C during analysis.

Chromatographic analysis of CA, MCA and their stable isotope labeled internal standards was achieved using 2% methanol containing 0.5 g/L PFOA for 4 min as mobile phase. The methanol concentration was increased to 85% at 4 min and to 95% at 6 min using linear gradient. A 2 min column re-conditioning step with 2% methanol containing 0.5 g/L PFOA was included after each injection. A constant flow rate of 400 μL/min was used in all experiments.

Analysis by MS/MS was in the positive ion mode using argon as collision gas with collision energy of 22 eV, capillary voltage of 3.4 kV and cone voltage of 35 V. Desolvation temperature of 120 °C and ion source temperature of 350 °C were applied. Detection was in the multiple reaction monitoring mode with m/z of 485 > 151 and 489 > 151 for CA and d4-CA, respectively. MCA and d3-MCA were detected using m/z 499 > 151 and 502 > 151 as previously described12,14.

Method validation

DBS calibrators used to create the standard curves were prepared using control blood spiked with CA and MCA in the range of 2.5–200 µmol/L and 0.25–16 µmol/L, respectively. Unspiked DBS samples were included in the analysis to account for analyte concentrations that present naturally in blood. To determine the intraday (n = 12) and interday (n = 12) variations, quality control DBS samples spiked with target analytes (Table 1) were used. To assess the analytical recovery, we analyzed DBS samples before and after enrichment at known analyte concentrations. Accuracy expressed as % error was determined from DBS specimens containing known analyte concentrations using the following formula: [Accuracy (%) = 100 × (concentration measured – concentration added)/concentration added].

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the manuscript. If required, additional data will be made available on reasonable request from the corresponding author [O.Y.A.].

References

Deodato, F., Boenzi, S., Santorelli, F. M. & Dionisi-Vici, C. Methylmalonic and propionic aciduria. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 142C, 104–112 (2006).

Wongkittichote, P., Ah Mew, N. & Chapman, K. A. Propionyl-CoA carboxylase – A review. Mol Genet Metab. 122, 145–152 (2017).

Longo, N. et al. Anaplerotic therapy in propionic acidemia. Mol Genet Metab. 122, 51–59 (2017).

Rossi, A. et al. Early-onset combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria: neuroradiologic findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 22, 554–563 (2001).

Fowler, B., Leonard, J. V. & Baumgartner, M. R. Causes of and diagnostic approach to methylmalonic acidurias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 31, 350–360 (2008).

Baumgartner, M. R. et al. Proposed guidelines for the diagnosis and management of methylmalonic and propionic acidemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 9, 130 (2014).

Kölker, S. et al. The phenotypic spectrum of organic acidurias and urea cycle disorders. Part 1: the initial presentation. J Inherit Metab Dis. 38, 1041–1057 (2015).

Kölker, S. et al. The phenotypic spectrum of organic acidurias and urea cycle disorders. Part 2: the evolving clinical phenotype. J Inherit Metab Dis. 38, 1059–1074 (2015).

Hori, D. et al. Clinical onset and prognosis of Asian children with organic acidemias, as detected by analysis of urinary organic acids using GC/MS, instead of mass screening. Brain Dev. 27, 39–45 (2005).

Schulze, A., Matern, D. & Hoffmann, G. F. Newborn Screening. In Pediatric Endocrinology and Inborn Errors of Metabolism.,Sarafoglou, K., Hoffmann, G.F., Roth, K.S., Eds., McGraw-Hill Medical: New York, USA, pp. 17–32 (2009).

Fraser, J. L. & Venditti, C. P. Methylmalonic and propionic acidemias: clinical management update. CurrOpinPediatr. 28, 682–693 (2016).

Al-Dirbashi, O. Y. et al. Analysis of methylcitrate in dried blood spots by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Inherit Metab Dis Rep. 16, 65–73 (2014).

Al-Dirbashi, O. Y., McIntosh, N. & Chakraborty, P. Quantification of 2-methylcitric acid in dried blood spots improves newborn screening for propionic and methylmalonic acidemias. J Med Screen 24, 58–61 (2017).

Al Dhahouri, N. et al. Quantification of methylcitrate in dried urine spots by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry for the diagnosis of propionic and methylmalonic acidemias. Clin Chim Acta. 487, 41–5 (2018).

Weidman, S. W. & Drysdale, G. R. The biosynthesis of methylcitrate. Biochem J. 177, 169–174 (1979).

Bhagavan, N. V. & Ha, C. E. Lipids I: Fatty acids and eicosanoids. In Essentials of Medical Biochemistry with Clinical Cases.Bhagavan, N.V., Ha, C.E., Eds., Academic Press: San Diego, USA, pp. 269–97 (2015).

Al-Dirbashi, O. Y., Santa, T., Al-Qahtani, K., Al-Amoudi, M. & Rashed, M. S. Analysis of organic acid markers relevant to inherited metabolic diseases by ultra-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry as benzofurazan derivatives. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 21, 1984–1990 (2007).

Al-Dirbashi, O. Y. et al. Diagnosis of glutaric aciduria type 1 by measuring 3-hydroxyglutaric acid in dried urine spots by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Inherit Metab Dis. 34, 173–180 (2011).

Turgeon, C. T. et al. Determination of total homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, and 2-methylcitric acid in dried blood spots by tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 56, 1686–1695 (2010).

Caruso, U., Lupino, S., Schiaffino, M. C. & Romano, C. Capillary GC-MS-stable isotope dilution analysis of methylmalonic acid in plasmas: a candidate reference method for the diagnosis and the follow-up of methylmalonic acidaemias. Chromatographia. 36, 212–214 (1993).

Jafari, P. et al. Brain damage in methylmalonic aciduria: 2-methylcitrate induces cerebral ammonium accumulation and apoptosis in 3D organotypic brain cell cultures. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 8, 4 (2013).

Cudré-Cung, H. P. et al. Ammonium accumulation is a primary effect of 2-methylcitrate exposure in an in vitro model for brain damage in methylmalonic aciduria. Mol Genet Metab. 119, 57–67 (2016).

Cheema-Dhadli, S., Leznoff, C. C. & Halperin, M. L. Effect of 2-methylcitrate on citrate metabolism: implications for the management of patients with propionic acidemia and methylmalonic aciduria. Pediatr Res. 9, 905–908 (1975).

Fraenkl, S. A. et al. Plasma citrate levels as a potential biomarker for glaucoma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 27, 577–580 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by UAE University grants 31M314 and 31M326 (OY Al-Dirbashi and F Al-Jasmi) and by funding from the DietmarHopp Foundation (JG Okun and GF Hoffmann).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.Y.A., M.A., A.A., J.H., J.G.O., G.F.H., and F.A. conceptualized the work and designed the experiments; N.A., Z.A., and C.D.L. performed the experiments; O.Y.A., M.A., K.A.T, A.A., J.H., J.G.O., G.F.H., and F.A. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Dirbashi, O.Y., Alfadhel, M., Al-Thihli, K. et al. Assessment of methylcitrate and methylcitrate to citrate ratio in dried blood spots as biomarkers for inborn errors of propionate metabolism. Sci Rep 9, 12366 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48885-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48885-9

This article is cited by

-

Anaplerosis in action

Nature Metabolism (2023)

-

Disrupted propionate metabolism evokes transcriptional changes in the heart by increasing histone acetylation and propionylation

Nature Cardiovascular Research (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.