Abstract

Methodological and technological advances in EPR spectroscopy have enabled novel insight into the structural and dynamic aspects of integral membrane proteins. In addition to an extensive toolkit of EPR methods, multiple spin labels have been developed and utilized, among them Gd(III)-chelates which offer high sensitivity at high magnetic fields. Here, we applied a dual labeling approach, employing nitroxide and Gd(III) spin labels, in conjunction with Q-band and W-band double electron-electron resonance (DEER) measurements to characterize the solution structure of the detergent-solubilized multidrug transporter MdfA from E. coli. Our results identify highly flexible regions of MdfA, which may play an important role in its functional dynamics. Comparison of distance distribution of spin label pairs on the periplasm with those calculated using inward- and outward-facing crystal structures of MdfA, show that in detergent micelles, the protein adopts a predominantly outward-facing conformation, although more closed than the crystal structure. The cytoplasmic pairs suggest a small preference to the outward-facing crystal structure, with a somewhat more open conformation than the crystal structure. Parallel DEER measurements with the two types of labels led to similar distance distributions, demonstrating the feasibility of using W-band spectroscopy with a Gd(III) label for investigation of the structural dynamics of membrane proteins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Distance measurement by DEER (double electron-electron resonance, also called PELDOR) is an established technique to track macromolecular structures1. It reports on the dipolar interaction between two electron spins, which can be converted into a distance due to its r−3 dependence, where r is the inter-spin distance. DEER measurements yield distance distributions, on the 1.5–8.0 nm scale, that can be extracted from the data using multiple approaches2,3. Two paramagnetic labels that are commonly, but not necessarily, of the same type are attached to proteins via site directed spin labeling (SDSL) to the thiol groups of native or genetically engineered cysteines4. The most commonly used spin label in DEER applications to proteins is MTSSL (S-(1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate). Its spectroscopic as well as biochemical advantages are well known and established5,6,7. However, there are instances when MTSSL is not the optimal spin label such as for in-cell applications where the paramagnetic nitroxide group is reduced to a diamagnetic hydroxyl amine8. Additionally, at high frequencies, like W-band (95 GHz), which are advantageous for high sensitivity9, data analysis of nitroxide DEER measurements can be complicated by orientation selection10. Therefore, alternatives to nitroxide spin labeling have been introduced in the past decade11,12,13, among them Gd(III) chelates, which are suitable for Q- and W-band frequencies (34 and 95 GHz, respectively) measurements14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Notably, at W-band they exhibit high sensitivity34 and the DEER traces are free of orientation selection effects35. Gd(III) is stable in reducing environments and so far most of the reported in-cell DEER measurements have employed Gd(III) labels16,29,36,37,38,39,40,41. Finally, having the choice of different spin labels allows for labeling strategies that afford measurement of three independent distances per sample as opposed to one distance provided by the standard two spin labels approach42.

DEER employing the MTSSL spin label has been applied to diverse membrane proteins with first applications appearing as early as 200443,44,45 in various environments including detergents46,47, bicelles48, nanodiscs49, lipodiscs50, nanoparticles50, and cell membranes51, with emphasis on the conformational states underlying transport mechanisms52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. The application of Gd(III) spin labels to membrane proteins have so far been limited to studying the oligomeric state of proteorhodopsin, showing that they are immune to multi-spin effects, which introduce uncertainties in the data analysis24. In addition, using a membrane embedded transmembrane model peptide25, it was shown that labeling the same two positions with Gd(III) spin labels or nitroxide spin labels yielded distance distributions different than those predicted, presumably because of their different interactions with the membrane owing to their different hydrophobicity. Therefore, employing DEER with different types of spin labels yields more detailed spatial information and possibly resolving context-dependent spin label effects.

In this work we applied DEER with MTSSL, measured at Q-band, and with a Gd(III) spin label, Gd-C2 (Fig. 1) measured at W-band. Using these labels we characterized the conformational behavior of the membrane protein MdfA, an Escherichia coli secondary multidrug transporter (Mdr)60. In addition, the suitability of Gd(III) spin labels for the study of membrane proteins was explored. Multidrug transporters are membrane proteins that are able to export a variety of structurally dissimilar compounds out of cells61. They play a vital role in cellular protection against a variety of potential cytotoxic compounds, including antibiotics. The prototypic secondary Mdr transporter MdfA operates as substrate/H+ antiporter, importing one equivalent H+ in every export cycle61.

MdfA is composed of 410 amino acid residues, organized in 12 transmembrane (TM) helices, with both N- and C- termini located in the cytoplasm62. Previous studies have suggested that MdfA is unusually flexible61, which may explain why the wild type protein has never yielded highly diffracting crystals. A hypothetical 3D model for wild type MdfA63 has received direct support from the high-resolution crystal structure of an MdfA mutant, MdfA(Q131R) with a trapped ligand (pdb 4ZP0) in an inward facing structure (If)64. This structure shows that, indeed, MdfA shares general structural characteristics of major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters65. These include the canonical MFS fold with two domains of six consecutive trans-membrane (TM) helices, termed the N- and C- domains, which exhibit a two-fold pseudosymmetry. More recently, a new structure of native MdfA bound to a FAB has been reported (pdb 6GV1) in an outward open conformation (Oo)66. The current model posits that during its transport cycle MdfA undergoes a conformational cycle which involves both the If and Oo conformations, with the Oo conformation possibly capturing the state that releases substrates into the periplasm67. Following its protonation, MdfA probably assumes a ligand occluded If conformation. Thus, the two structures offer a partial view on the conformational behavior of MdfA. Further crystallization efforts as well as biochemical and spectroscopic studies are needed to reveal additional conformational states. Specifically, understanding the functional dynamics of MdfA in its natural environment requires accurate distance constraints between regions in the protein that undergo movement during substrate binding and release.

We used DEER to elucidate the solution conformation of MdfA solubilized in detergent, in light of the recently published crystal structures64,66,68. For this purpose, we have labeled a series of double cysteine MdfA mutants with both MTSSL and C2-Gd, a Gd(III) tag (Fig. 1)69,70. Our studies included 13 double mutants labeled with both MTSSL and C2-Gd; eight of them designed to probe the periplasmic face of MdfA, and five, the cytoplasmic region. In addition, one more C2-Gd(III) and one more MTSSL labeled constructs were prepared and characterized. This labeling approach is similar to that used on the pioneering DEER application to lactose permease, LacY46. Distance distributions were evaluated to assess agreement with the two published crystal structures (see Fig. 2). Both spin labels show that the periplasmic side of detergent-solubilized MdfA has a structure more similar to the Oo conformation, while for the cytoplasmic face, the DEER distances show only a subtle preference for the Oo structure. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first extensive comparison of the two types of labels and it reveals a relatively general agreement between distances determined from the two types.

Results

Construction and characterization of spin-labeled variants of MdfA

Guided by the crystal structure of MdfA(Q131R)64, we modified several sites at the cytoplasmic or periplasmic edges of the TMs by cysteines (Fig. 2A), in the background of an active cysteine-less version of MdfA71. Initially, we assessed the Mdr activity of single cysteine mutants (Fig. S1) and those that retained function were selected for further analyses, including expression tests (Fig. S2A) and MTSSL accessibility (Fig. S2B). Single cysteine mutations were combined to generate double cysteine mutants at sites that did not compromise function and enabled efficient labeling at distances amenable to DEER measurements. Nine double cysteine mutants on the periplasmic side and six on the cytoplasmic side were selected based on their level of expression (Figs 2 and S3A) and Mdr activity (Fig. S3B). These mutants were overexpressed, purified as described earlier67, and labeled with either MTSSL or the C2-Gd tag (Fig. 1). Labeled samples were flash-frozen in liquid N2 for EPR studies. Table S1 in the Supplementary Information (SI) lists all the double mutants and their identification in terms of transmembrane helix location.

DEER measurements

In order to compare the various constructs and the different spin labels, all the EPR experiments were conducted at slightly alkaline pHs (7.2–7.5), under which the functional acidic residues are likely deprotonated72. Eight MdfA double cysteine variants were labeled in the periplasmic side with MTSSL, in the following referred to as NO, and C2-Gd, for a total of 16 constructs. Additionally, another double-mutant was labeled with only C2-Gd. Five pairs on the cytoplasmic side were labeled with both labels and one more with NO only (see Table S1). Examples of W-band and Q-band echo-detected EPR spectra of MdfA labeled with C2-Gd and NO, respectively, are shown in Fig. 3 with indicated positions of the pump and observe pulses in the DEER sequence. The C2-Gd labeled samples gave rather similar phase memory times in the range of 1.0–1.6 µs, allowing DEER evolution times as long as 4–5 μs.

Echo-detected EPR spectrum of (a) MdfA TM5163–TM9307 labeled with C2-Gd (10 K, W-band). The positions and range of the chirp pump pulses are indicated in light blue and the position of the observe pulses are indicated by an arrow. (b) MdfA TM5163–TM9307 labeled with NO (83 K, Q-band). The region affected by pump pulse is indicated in light blue, and the observe position is indicated by an arrow.

Figures 4 and 5 show the NO-NO and Gd(III)-Gd(III) DEER form factors obtained after background removal and the derived distance distributions of all measurements on the periplasmic and cytoplasmic side of the protein, respectively. The primary DEER data with the background correction function are shown in Figs S4 and S5. The data quality for the two types of labels is similar in terms of DEER signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), with the low modulation depth observed for C2-Gd compensated by the large echo intensity and enhanced by the use of an Arbitrary Waveform Generator (AWG) to produce shaped (linear chirp) pump pulses37,73,74. The distance distributions shown in Figs 4 and 5 were derived by model fitting to Gaussians using the DD software75. The results are similar to those derived by Tikhonov regularization obtained using the DeerAnalysis software2 (Figs S6 and S7). The DEER traces recorded on MdfA labeled with C2-Gd were typically longer (3.0–3.5 µs) than their NO counterparts (1.4–2.2 µs) owing to the longer distances of MdfA labeled with C2-Gd76. The data were analyzed to assess: (i) the agreement between the NO and C2-Gd results and (ii) their agreement with the distance distributions calculated using the crystal structures. In these comparisons we mostly referred to the maximum of the DEER distance distribution, represented by rmax, and in cases where the distance distribution was bimodal, we considered the major component. Table S1 lists all the rmax values.

DEER data for the periplasmic spin label pairs. (left panels) DEER form factors for MdfA labeled with either C2-Gd (upper panels, black traces) or NO (lower panels, green traces). Red traces indicate the fit using the distance distribution on the right; (right panels) DEER-derived distance distributions. The results were analyzed using DD and compared to a distance distribution calculated from the crystal structures 4ZP0 (If, red) and 6GV1 (Oo, blue). The shaded gray area denotes the confidence bands for the distance distribution.

DEER data for the cytoplasmic spin label pairs. (left panels) DEER form factors for MdfA labeled with either C2-Gd (upper panels, black traces) or NO (lower panels, green traces). Red traces indicate the fit using the distance distribution on the right; (right panels) DEER-derived distance distributions. The results were analyzed using DD and compared to a distance distribution calculated from the crystal structures 4ZP0 (If, red) and 6GV1 (Oo, blue). The shaded gray area denotes the confidence bands for the distance distribution.

Comparison of MdfA-C2-Gd and MdfA-NO distance distributions

C2-Gd and MTSSL differ in a number of properties that affect the DEER traces and consequently the resulting distance distributions. First, the distance between the spin bearing moiety and the cysteine sulfur in C2-Gd is longer than in MTSSL (0.93 nm vs 0.69 nm for an extended label conformation). Second, C2-Gd is larger than the MTSSL, and is positively charged compared to the hydrophobic neutral MTSSL. Yet, despite these different properties, Figs 4 and 5 show that in most cases the distance distributions measured with the two labels report similar structural information. A general trend of broad distance distributions emerged for both labels consistent with the expected conformational heterogeneity of MdfA. Figure 6a shows a correlation plot where the rmax values for MdfA labeled with C2-Gd are plotted against those of MdfA labeled with NO (considering rmax of the major distance component). While the correlation improves for longer distances, we observed notable differences for short distances. These differences could partially arise from the effect of the pseudo-secular terms of the dipolar interaction for short distances and small zero-field splitting although these were shown to mostly broaden the distance distribution rather than shifting the average distance20,77. Moreover, local perturbations due to the size of the Gd(III) label are expected to be independent of the distance between the labels.

(a) Plot of rmax for the C2-Gd labeled mutants vs rmax for the NO labeled ones. When more than 1 Gaussian appeared in the distance distribution, we considered only the major one. The blue, dashed line corresponds to a perfect match, whereas the red line is a linear fit. Mutant TM120–TM10335, which was removed from subsequent analysis as described in the text, is indicated by a black circle. (b) Plot of Δ(C2-Gd, NO)exp for each mutant studied, except for TM120–TM10335.

Figure 6b shows the difference between the position of the main distance distribution peak of NO and that of C2-Gd, Δ(C2-Gd,NO)exp = rmax(C2-Gd)-rmax(NO). This plot highlights that, in most cases, rmax for C2-Gd is larger as expected, but there is a variation in Δ(C2-Gd,NO)exp, on the range of 0–1.2 nm with large deviation for the construct TM120–TM10335. For four constructs we observed C2-Gd distances slightly shorter than those of the NO counterparts with TM6191-TM7222 showing the largest difference of 0.4 nm, indicating significant contributions from the labels’ relative orientations, conformation and local repacking. Correlation plots derived from distance distributions obtained by Tikhonov regularization show the same trend (Fig. S8). We observed that the construct TM120–TM10335, which showed a large difference between C2-Gd and NO, also exhibits a large deviation between the calculated and experimental distance distribution for C2-Gd, while for the NO results match reasonably well (see below). We suspect that the steric accommodation of the large Gd-C2 label at the buried TM10335 position is at the origin of this deviation. Thus, data from this mutant with C2-Gd will not be included further in the analysis.

Comparison of the width of the distance distributions for the two labels did not reveal a discernable overall trend suggesting that the width may be context dependent. For example, the distance distribution reported by the NO for TM144–TM9307 is significantly broader than that of C2-Gd. In contrast for TM5168–TM11373 and TM3101–TM8252 the trend is the opposite, with C2-Gd showing a broader width, while the width is comparable for the other pairs. We note that for distance distributions below 4 nm there could be artificial broadening contributions to the distance distributions of C2-Gd due to deviations from the weak-coupling approximation20,78.

Comparison of distance distributions with the crystal structures

To determine whether the structure of MdfA solubilized in detergent micelles in the apo state at pH 7.2–7.5 resembles either of the two crystal, we compared the experimental distance distributions with calculated distance distributions from the two crystal structures 4ZP0 and 6GV1 which are referred to as If and Oo, respectively (see Figs 4 and 5). The predicted distance distributions for the NO pairs were obtained using MMM79, whereas those for C2-Gd pairs were obtained using a different approach described in the experimental section. Correlation plots of the predicted rmax(NO) vs. predicted rmax(C2-Gd) for each of the crystal structures of MdfA, If and Oo, (Fig. S9) show that the calculated C2-Gd distances are larger than the corresponding NO distances, with a spread of 0 ≤ Δ(Gd,NO) ≤ 1 nm.

To highlight the differences between the two structures expected for each spin label pair, plots of Δ(If, Oo)calc, Gd = rmax(If, C2-Gd)calc − rmax(Oo, C2-Gd)calc and Δ(If, Oo)calc, NO = rmax(If, NO)calc − rmax(Oo, NO)calc are shown in Fig. 7. In the periplasm, there is a general trend towards larger distances in the Oo structure that is reflected by segregated negative data points. Differences above 1 nm are expected for 4 mutants labeled with NO and 3 mutants labeled with C2-Gd. In general, the calculated NO distances span a larger difference range than the C2-Gd distances, suggesting that it is more sensitive to the structural difference between If and Oo. In contrast, the differences are less conspicuous for the cytoplasmic mutants, where only one mutant, TM120–TM8280, is expected to exhibit a large difference. Here however, Gd-C2 is more sensitive to the change, except for TM120-TM8280. Thus, opening/closing of MdfA is less pronounced in the cytoplasmic region, at least for the selected pairs. Figure 7 highlights the advantages of using two different spin labels, showing that for a particular pair, the two spin labels can show different sensitivities to differences between the structures, such as in the case of TM120-TM8280.

Plots of Δ(If, Oo)calc for each of the mutants studied. It shows the expected change in the distance distribution between the two crystal structures. Pairs for which Δ(If, Oo)calc~0 are not sensitive in distinguishing between the two crystal structures. For mutants indicated with an asterisk (*), only NO or C2-Gd experimental data are available.

In order to assess the correlation between the experimental data and the crystal structures, we plotted the calculated rmax from the crystal structures against the rmax from the measured data (see Fig. 8). We observed a more robust agreement with the Oo crystal structure for both spin labels (panels a and c). For NO a linear fit gave a slope of 0.96 and a R2 of 0.86, which is close to the slope of 1, as would be expected for direct correspondence. For C2-Gd, the correlation is less ideal, yielding a slope of 1.42 with a R2 of 0.76. The correlations with the If structure, shown in panels b and d, yielded a slope of 0.49 with an R2 of 0.11 for C2-Gd and a slope of 0.45 with an R2 of 0.40 for NO, indicating a quantitative agreement between the DEER data and the Oo conformation, but not the If conformation.

Comparison of the experimental and crystal structure derived rmax values for C2-Gd and rmax calculated from the (a) Oo structure, (b) If structure and the same for the NO labels (c,d) respectively. When more than one Gaussian appeared in the distance distribution, we considered only the major one. The dashed blue line corresponds to a perfect match, whereas the red line is a linear fit.

To allow for a more detailed comparison with the crystal structures, Fig. 9 highlights the differences between the crystal structures and the experimental rmax values for each spin label pair, Δ(Oo, exp)C2-Gd = rmax(Oo, C2-Gd)calc − rmax(C2-Gd)exp, Δ(Oo, exp,)NO = rmax(Oo, NO)calc − rmax(NO)exp and accordingly for If. Several general trends are noted: (i) the overall deviation from the crystal structure (indicated by larger absolute values) is larger for the periplasmic face of the If structure, and the scatter between NO and C2-Gd data is comparable. (ii) The correspondence with the structures is more similar for the cytoplasmic face mutants.

Plots showing the difference between the predicted and experimental rmax values (a) for the Oo structure for the mutants studied (red symbols are for C2-Gd, Δ(Oo, exp)C2-Gd, and black for NO, Δ(Oo, exp)NO); (b) the same for the If structure (Δ(If, exp)C2-Gd, (Δ(If, exp)NO). The vertical dotted blue lines mark the zero lines (perfect agreement) and the horizontal black lines represent the division between periplasmic and cytoplasmic pairs. The mutants marked with * were labeled with only one type of spin label.

Comparison to the Oo crystal structure (Fig. 9a) shows that for the periplasmic pairs the majority of the points are positive, indicating a more closed conformation of detergent-solubilized MdfA compared to the crystal structure. The C2-Gd labeled TM5168–TM9310 is identified as the largest outlier on the periplasmic side (0.9 nm). Also notable are the constructs TM5163–TM10315 and TM120–TM7222, on the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides, respectively, which exhibit the largest difference between NO and C2-Gd distances. On the cytoplasmic face, the majority of the points are negative, suggesting a more open conformation as compared to the Oo crystal structure. Here the C2-Gd labeled mutant TM120–TM8280 (~0.9 nm) as well as the NO-labeled TM120–TM7222 (~0.6 nm) display the largest deviation.

Figure 9b shows the same data for the If crystal structure. In contrast to Oo, most points are negative indicating longer distances in the periplasmic side for the detergent solubilized conformations. The largest absolute deviation in the periplasm was found for mutants TM144–TM9307 and TM144–TM10315 (~1.8 nm each) for C2-Gd and, TM144–TM10315 (~2.0 nm) for NO. The largest scatter between NO and C2-Gd in the periplasm is observed for the mutant TM5163–TM11373 (0.7 nm) and is in the same order of magnitude as for the Oo conformation. In the cytoplasm, most of the points are negative, with three on the positive side with large deviations. TM120–TM8280 yields the largest absolute deviation (1.5 nm) as well as the largest Δ(C2-Gd, NO)exp scatter (1.8 nm). TM120–TM7222, which showed the largest scatter in the Oo conformation, shows a similarly large deviation at 1.5 nm. While a clear distinction between the two structures was observed for the periplasmic pairs, the cytoplasmic pairs show only a slight preference towards the Oo structure, suggesting a somewhat more open conformation. This is in agreement with Fig. 7, which shows that the difference between the structures for the cytoplasmic pairs is expected to be small.

Interestingly, while for TM5163–TM9307 both labels deviate significantly from the Oo predictions (0.5 nm for both C2-Gd and NO), they agree with the If prediction (Fig. 9b). The spin label pairs that are predicted to show the largest differences between the structures are TM144–TM9307, TM120–TM8280 and TM3101–TM11373 (see also Fig. 7). Out of these only TM3101–TM11373 gives an excellent agreement with Oo and a poor one with If for both labels. Similar discrimination is reported by NO-labeled TM120–TM8280, but not its C2-Gd counterpart. We also compared the experimentally determined distance distributions calculated with Tikhonov regularization (Figs S10 and S11), and obtained similar results, reinforcing our conclusion that that the DEER measurements agree significantly better with the Oo structure, as compared to the If structure for the periplasmic face.

Discussion

In this work, we have explored the conformation of MdfA solubilized in detergent at pH = 7.2-7.5. We used two different spin labels with very different chemical properties and sizes in order to eliminate label-specific effects on the distance distribution and to test the applicability of Gd(III) spin labeling to membrane proteins in a systematic way. The results reported by the two labels are consistent and show that in the apo state MdfA favors the Oo crystal structure66. Nonetheless, there are some notable differences between the predicted and the experimental distance distributions: (i) While the periplasmic pairs show a clear preference for the Oo structure, the cytoplasmic pairs exhibit only a marginal preference for the Oo structure (Fig. 9); (ii) The periplasmic region seems to be more “closed” in detergent solution than in the Oo crystal structure, whereas the cytoplasmic side is more open. This opposite movement of the periplasmic and cytoplasmic faces is consistent with the alternating access model found earlier on for LacY46 and it shows that in the apo state the protein solubilized in detergent is in a conformation ready for the uptake of the substrate. (iii) The largest deviations for both labels were observed with TM5163–TM9307 and TM5168–TM11373, and for TM5168–TM9310 which was labeled only with C2-Gd. This is not surprising, because residues 163 and 168 are located at the periplasmic edge of TM5, which was proposed to exhibit major movements during the transition from the If conformation to the Oo one66. On the cytoplasmic face, distance distributions for the TM120–TM7222 pair exhibit the largest discrepancy between C2-Gd and NO and are incongruent with the predicted distance distributions of either Oo or If crystal structures, indicating the possibility of spin label distortion of local structure. We suspect that the large size of the C2-Gd label led to a significant structural distortion at the cytosolic site TM10335, which is located close to the putative recognition pocket.

The differences between the crystal structures and the measured DEER distances in detergent-solubilized MdfA may reflect the imposed constraints on the protein in the crystalized state. In the Oo structure this could be the Fab fragment, which freezes the cytoplasmic face in a certain conformation. In the If crystal structure the insertion of a rather inactivating mutation67 possibly locked the protein in an inactive crystallisable conformation. In both cases, the crystal structures might not represent the most probable natively occurring steady state conformations of MdfA.

While the discussion above focused on rmax values, the width of the distance distribution is another parameter that can report directly on flexible, disordered parts of the transporter. Large deviations from the calculated width, which account for the contributions of the flexibility of the spin-label tether, may indicate local disorder in the protein. The calculated distance distribution (Figs 4 and 5) shows that for C2-Gd the width is somewhat larger (gross estimates, 20–50%) than for NO except for TM144–TM9307. In general, the experimental distance distributions are broader than the calculated ones, particularly for the cytoplasmic pairs (except for TM120–TM8280), suggesting increased flexibility on this side of the transporter. There are cases where the two spin labels exhibit significant width, and others such as TM5168–TM11373 and TM3101–TM8252 that are broader for C2-Gd and TM144–TM9307 and TM5163–TM11373 that are broader for NO. TM3101–TM11373 displays a relatively narrow distance distribution, in agreement with the calculated one. Finally, lipids have been demonstrated to shift the equilibrium between conformational states54, thus, a detailed investigation of MdfA conformational dynamics will require studies in membrane mimetics such as liposomes or nanodiscs.

Conclusions

DEER measurements on a series of double mutants of MdfA labeled with two different spin labels, nitroxide and C2-Gd, were carried out in order to compare the conformation and flexibility of MdfA solubilized in detergent solution to the two crystal structures. To our knowledge, this study represents the most extensive comparison of DEER data, obtained with Gd(III) and nitroxide spin labels, on a protein. Both labels, which are dissimilar in their structures, sizes, charge and hydrophobicities, yielded consistent results. In addition to revealing the flexibility of detergent-solubilized MdfA, the results show that the periplasmic side has a similar structure to the Oo conformation reported by the 6GV1 crystal structure, though somewhat more closed, and is quite different from the If crystal structure. For the cytoplasmic face the results show only a slight preference for the Oo with a more open conformation.

Methods

Strains, plasmids, and mutants

All experiments were conducted with E. coli UTL280 derivative (UTL2mdfA::Kan). Plasmid pT7-5/200us/CL-mdfA-6His was used for resistance, expression and analysis of protein labeling experiments. Plasmid pUC18/Para/CL-mdfA-6His was used for overexpression. All mutants were generated using a standard PCR method with mutagenic oligonucleotide primers and a plasmid encoding cysteine-less (CL) MdfA as a template71. The plasmids were verified by sequencing.

Drug resistance assay

Antibacterial resistance was assayed as described81. Briefly, E. coli UTL2mdfA::Kan harboring empty vector or expressing MdfA variants were grown aerobically to A600 of ~1 and a series of 10-fold dilutions was prepared. 4 μl of the serial dilutions were spotted on drug-containing LB-agar plates and tested for growth after overnight incubation at 37 °C.

Expression analysis

Overnight cultures of E. coli UTL2mdfA::Kan harboring empty vector or expressing CL-MdfA or variants were diluted 1:100 and grown to A600 of 0.8–1. Cells were harvested and resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol), supplemented with 1 mM PMSF. Cells were sonicated three times at 50%, 10 s on, 10 s off and debris were removed by centrifugation (5 min, top speed in a table-top centrifuge, at 4 °C). The supernatant was then centrifuged at 244,000 g for 30 min to pellet the membranes. Membranes were resuspended in buffer A and the total membrane protein concentration was analyzed by Lowry. Samples (20 µg or total membrane protein) were then subjected to 12.5% (w/v) SDS/PAGE, electroblotting, and detection using India HisProbe-horseradish peroxidase (Pierce) and ECL.

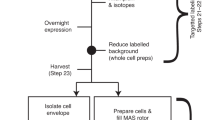

MdfA expression and purification

For all experiments, E. coli cells, harboring plasmid pUC18/Para/CL-mdfA-6His or any of the mutated constructs, were grown at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (200 μg/mL) and kanamycin (30 µg/ml). Overnight cultures were diluted to ~ 0.05 A600 units, grown to 0.8 A600 units, and induced with 0.2% (w/v) arabinose for 1.5 h at 37 °C. For C2-Gd experiments, E. coli cells were grown at 37 °C in LB supplemented with ampicillin (200 μg/mL) and kanamycin (30 μg/mL) until an OD of 0.8 was reached, transferred to 16 °C and induced with 0.2% (w/v) arabinose overnight. Exceptions were made for mutants TM5163–TM10315, TM120–TM7222, and TM120–TM10335 as part of an upgraded protocol. Here, E. coli cells were grown at 37 °C in Terrific Broth rich medium supplemented with ampicillin (200 μg/mL) and kanamycin (30 μg/mL) overnight. Subsequent induction was performed with 0.2% (w/v) arabinose for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Cell pellets were centrifuged for 30 min at 6,000 g and resuspended in 50 mM KPi pH 7.3 supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4. DNAse, 10 μg/mL, and PMSF, 1 mM, were then added and the cells passed three times through a pressure cell homogenizer (Stansted) at 15 kPsi for disruption. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (15 min, 20,000 g), and the membranes were collected by ultracentrifugation (1 h, 167,000 g). The membranes were suspended by homogenization in 20 mM tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

For MdfA purification, 5 mM of imidazole and 2 mM of β-mercaptoethanol were added to thawed membranes, which were then solubilized by addition of 20% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM, Anatrace) to a final concentration of 1.1%. Insoluble material was discarded by ultracentrifugation (30 min, 167,000 g) and the soluble fraction was mixed with solubilization buffer-equilibrated Talon beads (Clontech) (typically 0.5 mL bed volume for 2.5 gm of thawed membranes). Next, the mixture was agitated for 2 hr at 4 °C and the suspension was poured into a column and washed with 30 column volumes of solubilization buffer (20 mM tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM imidazole, 0.1% DDM). MdfA was eluted in 20 mM tris-HCl pH 7.2 or 7.5, 0.12 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% DDM, 200 mM imidazole. Protein concentration was determined by measuring A280 (1 mg/mL ~ 2.1 A280)82.

Labeling with MTSSL and preparation of DEER samples

Labeling was done by adding 20-fold molar excess of MTSSL (100 mM, in DMF) to the eluted protein. The sample was then incubated at room temperature (RT) for 1.5 h after which 20-fold molar excess of MTSSL was added again, and the protein was incubated for an additional 1 h at RT. The sample was kept on ice overnight. The protein was loaded onto Superdex 200 10/30 GL (GE Healthcare) size exclusion chromatography column in 20 mM tris-HCl pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.03% DDM. The protein was then concentrated to 75–100 μM using a 100 K MWCO concentrator (Amicon) and glycerol was added to a final concentration of 23.78% (v/v). SEC elution profiles are shown in Fig. S12. In each case, the major monodispersed fraction was collected and used for the experiment.

Labeling with C2-Gd and preparation of DEER samples

C2 was synthesized as reported earlier69,70. Labeling was done by adding 10-fold molar excess of the C2 label previously loaded with Gd3+ (50 mM in H2O) to the eluted protein. The sample was incubated for 12 h at 4 °C followed by 12 h of dialysis against dialysis buffer (20 mM tris-HCl pH 7.2, 0.12 M NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.01% DDM). In the next step the protein was incubated with Talon beads (Clonetech). Bed volume was in the range of 100–150 μl, depending on the volume of the sample after dialysis. The mixture was agitated for 2 h at 4 °C, washed, and consequently eluted with elution buffer (20 mM tris-HCl pH 7.2 or 7.5, 0.12 M NaCl, 10% glycerol-d8, 0.1% DDM, 200 mM imidazole, D2O). Protein concentration was determined by measuring A280 (1 mg/mL ~ 2.1 A280)82 and the protein concentrated to a final concentration of 20–50 μM using a 100 K MWCO concentrator (Amicon) and the sample loaded in 0.6 mm quartz capillaries.

Analysis of protein labeling

Membranes were prepared as described above, the total membrane concentration was adjusted to 3.5 µg/µl and aliquoted to 400 µl. Membranes were then solubilized by adding 20% DDM to a final concentration of 1.1% and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with tilting. Solubilized protein was recovered by centrifugation (100,000 g, 30 min, 4 °C), and divided into two equal portions. MTSSL (50 mM, 50% DMSO) was added to one of the portions at a final concentration of 1.25 mM and the same volume of 50% DMSO without MTSSL was added to the second portion. The two samples were then incubated at RT for 2 hr, after which 20 µl of suspended Talon beads (Clontech) were added to each, and incubated at 4 °C, for 1 h. Unbound protein was removed by centrifugation (700 g, 2 min) and the beads were washed twice with 300 µl of solubilization buffer. The protein was eluted with 2 × 32.5 µl of elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2, 0.12 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 150 mM imidazole, 0.1% DDM). SDS was then added to both samples, at a final concentration of 1%, and Mal-PEG(5000) (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 2 mM. Samples were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C, and for an additional 1 h and 45 min at RT in the dark. Non-reducing sample buffer was then added, incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, and 20 µl of the entire reaction was then subjected to 12.5% (w/v) SDS/PAGE, electroblotting, and detection using India HisProbe-horseradish peroxidase and ECL.

DEER measurements

C2-Gd DEER experiments were performed on a home-built 95 GHz (W-band) EPR spectrometer equipped with two microwave channels and a 2 W solid-state amplifier83,84 using the controller software SpecMan85. Shaped pulses were generated by a Chase Scientific DA12000 Arbitrary Waveform Generator (AWG) with a sampling rate of 2 GS/s in an incoherent manner. Details on the AWG set-up and performance have been published elsewhere37,73.

The C2-Gd DEER experiments were recorded at 10 K with (i) the standard dead-time free DEER sequence86 (ii) a 4-pulse DEER sequence where the pump pulse was replaced with a linear chirp73,74, referred to as AWG DEER or (iii) rDEER, where the shaped pump pulse is swept between the primary echo and the first refocusing pulse37. An 8-step phase cycling on the observer pulses was used; the observer pulse lengths were tπ, obs = 30 ns while the pump pulse lengths as well as other parameters varied. The experimental details on the different experiments are shown in Table S2.

NO DEER experiments were performed on E-580 Q-band EPR spectrometer (Bruker) at 83 K with the standard 4-pulse, dead-time free DEER sequence86. Two-step phase cycling on the observer pulses was used with observer pulse lengths of tπ/2,obs = 12 ns and tπ,obs = 24 ns.

The raw data was analyzed with DeerAnalysis 20182 using Tikhonov regularization (Figures in the SI) and with the DD program (Figures in the main text)3,75. Validation was performed with DeerAnalysis 2018 using 10 trials of level 1.5 white noise, and 11 trials of background starting from 500 ns–700 ns up to 1400 ns–1600 ns (exact numbers depend on the trace length).

Calculation of Gd-Gd distance distributions from crystal structures

To directly relate the measured DEER distance distributions to the crystal structures of MdfA, we modelled the most likely distance distributions between spin labels by taking into account the physicochemical properties of the tags using a procedure described previously87. First, the C2-Gd tag was grafted onto a single cysteine residue. Second, tag conformations were generated by random variation of the dihedral angles between the Cα atom and the amide of the of the ethylene thio linker of the C2-Gd tag, allowing free rotation around the N-C bond while restricting the sampling to staggered conformations around C-C bonds and dihedral angles of 90° or −90° for the S-S bond with an uncertainty range of ±10°. The protein coordinates were kept fixed and conformers with steric clashes between tag and protein were eliminated. To account for possible sidechain mobility of neighbouring residues in the structure, van der Waals radii in these calculations were scaled down by 10%. For each tag position 5000 random variations were calculated to obtain >400 conformers without steric clashes. Gd-Gd distance distribution were then calculated from all pair-wise distances of the Gd positions in the different tag conformations at two labelling positions.

References

Jeschke, G. Distance Measurements in the Nanometer Range by Pulse EPR. Chem. Phys. Chem. 3, 927–932, https://doi.org/10.1002/1439-7641(20021115)3:11<927::AID-CPHC927>3.0.CO;2-Q (2002).

Jeschke, G. et al. DeerAnalysis2006 - a Comprehensive Software Package for Analyzing Pulsed ELDOR Data. Appl. Magn. Reson. 30, 473–498 (2006).

Brandon, S., Beth, A. H. & Hustedt, E. J. The Global Analysis of DEER Data. J. Magn. Reson. 218, 93–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2012.03.006 (2012).

Jeschke, G. DEER Distance Measurements on Proteins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 63, 419–446, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143716 (2012).

McHaourab, H. S., Steed, P. R. & Kazmier, K. Toward the Fourth Dimension of Membrane Protein Structure: Insight into Dynamics from Spin-Labeling EPR Spectroscopy. Structure 19, 1549–1561, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2011.10.009 (2011).

Polyhach, Y. et al. High Sensitivity and Versatility of the DEER Experiment on Nitroxide Radical Pairs at Q-Band Frequencies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 10762–10773, https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cp41520h (2012).

Bordignon, E. In EPR Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Methods Vol. 1 (eds Daniella Goldfarb & Stefan Stoll) Ch. 14, 277 (Wiley-VCH, 2018).

Azarkh, M., Okle, O., Eyring, P., Dietrich, D. R. & Drescher, M. Evaluation of Spin Labels for in-Cell EPR by Analysis of Nitroxide Reduction in Cell Extract of Xenopus Laevis Oocytes. J. Magn. Reson. 212, 450–454, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2011.07.014 (2011).

Cruickshank, P. A. et al. A Kilowatt Pulsed 94 GHz Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectrometer with High Concentration Sensitivity, High Instantaneous Bandwidth, and Low Dead Time. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 80, 103102, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3239402 (2009).

Polyhach, Y., Godt, A., Bauer, C. & Jeschke, G. Spin Pair Geometry Revealed by High-Field DEER in the Presence of Conformational Distributions. J. Magn. Reson. 185, 118–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2006.11.012 (2007).

Yang, Z. et al. Pulsed ESR Dipolar Spectroscopy for Distance Measurements in Immobilized Spin Labeled Proteins in Liquid Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9950–9952, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja303791p (2012).

Ghosh, S., Lawless, M. J., Rule, G. S. & Saxena, S. The Cu2+-Nitrilotriacetic Acid Complex Improves Loading of Alpha-Helical Double Histidine Site for Precise Distance Measurements by Pulsed ESR. J. Magn. Reson. 286, 163–171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2017.12.005 (2018).

Banerjee, D., Yagi, H., Huber, T., Otting, G. & Goldfarb, D. Nanometer-Range Distance Measurement in a Protein Using Mn2+ Tags. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 157–160, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz201521d (2012).

Prokopiou, G. et al. Small Gd(III) Tags for Gd(III)-Gd(III) Distance Measurements in Proteins by EPR Spectroscopy. Inorg. Chem. 57, 5048–5059, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00133 (2018).

Mahawaththa, M. C. et al. Small Neutral Gd(III) Tags for Distance Measurements in Proteins by Double Electron-Electron Resonance Experiments. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 23535–23545, https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cp03532f (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. A Reactive, Rigid Gd(III) Labeling Tag for in-Cell EPR Distance Measurements in Proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 2914–2918, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201611051 (2017).

Yang, Y. et al. Generic Tags for Mn(II) and Gd(III) Spin Labels for Distance Measurements in Proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 26944–26956, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cp04311b (2017).

Welegedara, A. P. et al. Double-Arm Lanthanide Tags Deliver Narrow Gd3+ -Gd3+ Distance Distributions in Double Electron-Electron Resonance (DEER) Measurements. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 11694–11702, https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201702521 (2017).

Feintuch, A., Otting, G. & Goldfarb, D. Gd3+ Spin Labeling for Measuring Distances in Biomacromolecules: Why and How? Methods Enzymol. 563, 415–457, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.mie.2015.07.006 (2015).

Dalaloyan, A. et al. Gd(III)-Gd(III) EPR Distance Measurements - the Range of Accessible Distances and the Impact of Zero Field Splitting. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 18464–18476, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5cp02602d (2015).

Abdelkader, E. H. et al. A New Gd3+ Spin Label for Gd3+-Gd3+ Distance Measurements in Proteins Produces Narrow Distance Distributions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 5016–5021, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02451 (2015).

Abdelkader, E. H. et al. Protein Conformation by EPR Spectroscopy Using Gadolinium Tags Clicked to Genetically Encoded P-Azido-L-Phenylalanine. Chem. Commun. 51, 15898–15901, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5cc07121f (2015).

Goldfarb, D. Gd3+ Spin Labeling for Distance Measurements by Pulse EPR Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 9685–9699, https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cp53822b (2014).

Edwards, D. T. et al. Determining the Oligomeric Structure of Proteorhodopsin by Gd3+-Based Pulsed Dipolar Spectroscopy of Multiple Distances. Structure 22, 1677–1686, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2014.09.008 (2014).

Matalon, E. et al. Gadolinium(Iii) Spin Labels for High-Sensitivity Distance Measurements in Transmembrane Helices. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 11831–11834, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201305574 (2013).

Yagi, H. et al. Gadolinium Tagging for High-Precision Measurements of 6 Nm Distances in Protein Assemblies by EPR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10418–10421, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja204415w (2011).

Potapov, A. et al. Nanometer-Scale Distance Measurements in Proteins Using Gd3+ Spin Labeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 9040–9048, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja1015662 (2010).

Potapov, A. et al. Distance Measurements in Model Bis-Gd(III) Complexes with Flexible “Bridge”. Emulation of Biological Molecules Having Flexible Structure with Gd(III) Labels Attached. J. Magn. Reson. 205, 38–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2010.03.019 (2010).

Mascali, F. C., Ching, H. Y., Rasia, R. M., Un, S. & Tabares, L. C. Using Genetically Encodable Self-Assembling Gd(III) Spin Labels to Make in-Cell Nanometric Distance Measurements. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 11041–11043, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201603653 (2016).

Barthelmes, D. et al. Encoded Loop-Lanthanide-Binding Tags for Long-Range Distance Measurements in Proteins by Nmr and EPR Spectroscopy. J. Biomol. NMR 63, 275–282, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10858-015-9984-x (2015).

Gmeiner, C., Dorn, G., Allain, F. H. T., Jeschke, G. & Yulikov, M. Spin Labelling for Integrative Structure Modelling: A Case Study of the Polypyrimidine-Tract Binding Protein 1 Domains in Complexes with Short Rnas. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 28360–28380, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cp05822e (2017).

Shah, A. et al. A Gadolinium Spin Label with Both a Narrow Central Transition and Short Tether for Use in Double Electron Electron Resonance Distance Measurements. Inorg. Chem. 58, 3015–3025, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02892 (2019).

Song, Y. et al. Pulsed Dipolar Spectroscopy Distance Measurements in Biomacromolecules Labeled with Gd(III) Markers. J. Magn. Reson. 210, 59–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2011.02.010 (2011).

Raitsimring, A. et al. Optimization of Pulsed-DEER Measurements for Gd-Based Labels: Choice of Operational Frequencies, Pulse Durations and Positions, and Temperature. Appl. Magn. Reson. 44, 649–670, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00723-012-0434-6 (2013).

Raitsimring, A. M. et al. Gd3+ Complexes as Potential Spin Labels for High Field Pulsed EPR Distance Measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14138–14139, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja075544g (2007).

Yang, Y., Yang, F., Li, X. Y., Su, X. C. & Goldfarb, D. Distance Measurements on Ubiquitin Labeled with a Rigid Pymta-Gd(III) Tag. J. Phys. Chem. B 123, 1050–1059, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b11442 (2019).

Bahrenberg, T., Yang, Y., Goldfarb, D. & Feintuch, A. rDEER: A Modified DEER Sequence for Distance Measurements Using Shaped Pulses. Magnetochemistry 5, https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5010020 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. High Sensitivity in-Cell EPR Distance Measurements on Proteins Using an Optimized Gd(III) Spin Label. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 6119–6123, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b02663 (2018).

Theillet, F. X. et al. Structural Disorder of Monomeric Alpha-Synuclein Persists in Mammalian Cells. Nature 530, 45–50, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16531 (2016).

Qi, M., Gross, A., Jeschke, G., Godt, A. & Drescher, M. Gd(III)-Pymta Label Is Suitable for in-Cell EPR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15366–15378, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja508274d (2014).

Martorana, A. et al. Probing Protein Conformation in Cells by EPR Distance Measurements Using Gd3+ Spin Labeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13458–13465, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja5079392 (2014).

Wu, Z. et al. Selective Distance Measurements Using Triple Spin Labeling with Gd3+, Mn2+, and a Nitroxide. J Phys Chem Lett 8, 5277–5282, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b01739 (2017).

Jeschke, G., Wegener, C., Nietschke, M., Jung, H. & Steinhoff, H. J. Interresidual Distance Determination by Four-Pulse Double Electron-Electron Resonance in an Integral Membrane Protein: The Na+/Proline Transporter Putp of Escherichia Coli. Biophys. J. 86, 2551–2557, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3495(04)74310-6 (2004).

Hilger, D. et al. Assessing Oligomerization of Membrane Proteins by Four-Pulse DEER: Ph-Dependent Dimerization of NhaA Na+/H+ Antiporter of E. coli. Biophys. J. 89, 1328–1338, https://doi.org/10.1529/biophysj.105.062232 (2005).

Xu, Q., Ellena, J. F., Kim, M. & Cafiso, D. S. Substrate-Dependent Unfolding of the Energy Coupling Motif of a Membrane Transport Protein Determined by Double Electron-Electron Resonance. Biochemistry 45, 10847–10854, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi061051x (2006).

Smirnova, I. et al. Sugar Binding Induces an Outward Facing Conformation of Lacy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16504–16509, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708258104 (2007).

Pliotas, C. et al. Conformational State of the MscS Mechanosensitive Channel in Solution Revealed by Pulsed Electron-Electron Double Resonance (PELDOR) Spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E2675–2682, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1202286109 (2012).

Georgieva, E. R., Ramlall, T. F., Borbat, P. P., Freed, J. H. & Eliezer, D. Membrane-Bound Alpha-Synuclein Forms an Extended Helix: Long-Distance Pulsed ESR Measurements Using Vesicles, Bicelles, and Rodlike Micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 12856–12857, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja804517m (2008).

Zou, P. & McHaourab, H. S. I. Sensitivity and Extended Range of Distance Measurements in Spin-Labeled Membrane Proteins: Q-Band Double Electron-Electron Resonance and Nanoscale Bilayers. Biophys. J. 98, L18–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4193 (2010).

Sahu, I. D. et al. DEER EPR Measurements for Membrane Protein Structures Via Bifunctional Spin Labels and Lipodisq Nanoparticles. Biochemistry 52, 6627–6632, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi4009984 (2013).

Joseph, B. et al. Distance Measurement on an Endogenous Membrane Transporter in E. coli Cells and Native Membranes Using EPR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 6196–6199, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201501086 (2015).

Timachi, M. H. et al. Exploring Conformational Equilibria of a Heterodimeric ABC Transporter. Elife 6, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.20236 (2017).

Verhalen, B. et al. Energy Transduction and Alternating Access of the Mammalian ABC Transporter P-Glycoprotein. Nature 543, 738–741, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21414 (2017).

Martens, C. et al. Lipids Modulate the Conformational Dynamics of a Secondary Multidrug Transporter. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 744–751, https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3262 (2016).

Kusakizako, T. et al. Structural Basis of H+-Dependent Conformational Change in a Bacterial MATE Transporter. Structure, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2018.10.004 (2018).

Claxton, D. P., Jagessar, K. L., Steed, P. R., Stein, R. A. & McHaourab, H. S. Sodium and Proton Coupling in the Conformational Cycle of a MATE Antiporter from Vibrio Cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E6182–e6190, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1802417115 (2018).

Mishra, S. et al. Conformational Dynamics of the Nucleotide Binding Domains and the Power Stroke of a Heterodimeric ABC Transporter. Elife 3, e02740, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.02740 (2014).

Hanelt, I., Wunnicke, D., Bordignon, E., Steinhoff, H. J. & Slotboom, D. J. Conformational Heterogeneity of the Aspartate Transporter Glt(Ph). Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 210–214, https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2471 (2013).

Masureel, M. et al. Protonation Drives the Conformational Switch in the Multidrug Transporter LmrP. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 149–155, https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1408 (2014).

Yardeni, E. H., Zomot, E. & Bibi, E. The Fascinating but Mysterious Mechanistic Aspects of Multidrug Transport by MdfA from Escherichia Coli. Res. Microbiol. 169, 455–460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2017.09.004 (2018).

Fluman, N. & Bibi, E. Bacterial Multidrug Transport through the Lens of the Major Facilitator Superfamily. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794, 738–747, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.020 (2009).

Adler, J. & Bibi, E. Membrane Topology of the Multidrug Transporter MdfA: Complementary Gene Fusion Studies Reveal a Nonessential C-Terminal Domain. J. Bacteriol. 184, 3313–3320 (2002).

Sigal, N. et al. 3d Model of the Escherichia Coli Multidrug Transporter MdfA Reveals an Essential Membrane-Embedded Positive Charge. Biochemistry 44, 14870–14880, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi051574p (2005).

Heng, J. et al. Substrate-Bound Structure of the E. coli Multidrug Resistance Transporter MdfA. Cell Res. 25, 1060–1073, https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2015.94 (2015).

Yan, N. Structural Biology of the Major Facilitator Superfamily Transporters. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 44, 257–283, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-033901 (2015).

Nagarathinam, K. et al. Outward Open Conformation of a Major Facilitator Superfamily Multidrug/H+ Antiporter Provides Insights into Switching Mechanism. Nat. Commun. 9, 4005, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06306-x (2018).

Zomot, E. et al. A New Critical Conformational Determinant of Multidrug Efflux by an Mfs Transporter. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 1368–1385, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2018.02.026 (2018).

Nagarathinam, K. et al. The Multidrug-Resistance Transporter MdfA from Escherichia Coli: Crystallization and X-Ray Diffraction Analysis. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 73, 423–430, https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053230x17008500 (2017).

Lee, M. D. et al. Compact, Hydrophilic, Lanthanide-Binding Tags for Paramagnetic Nmr Spectroscopy. Chem. Sci. 6, 2614–2624, https://doi.org/10.1039/C4SC03892D (2015).

Graham, B. et al. DOTA-Amide Lanthanide Tag for Reliable Generation of Pseudocontact Shifts in Protein Nmr Spectra. Bioconjugate Chem. 22, 2118–2125, https://doi.org/10.1021/bc200353c (2011).

Adler, J. & Bibi, E. Determinants of Substrate Recognition by the Escherichia Coli Multidrug Transporter MdfA Identified on Both Sides of the Membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8957–8965, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M313422200 (2004).

Fluman, N., Ryan, C. M., Whitelegge, J. P. & Bibi, E. Dissection of Mechanistic Principles of a Secondary Multidrug Efflux Protein. Mol. Cell 47, 777–787, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.018 (2012).

Bahrenberg, T. et al. Improved Sensitivity for W-Band Gd(III)-Gd(III) and Nitroxide-Nitroxide DEER Measurements with Shaped Pulses. J. Magn. Reson. 283, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2017.08.003 (2017).

Doll, A. et al. Gd(III)-Gd(III) Distance Measurements with Chirp Pump Pulses. J. Magn. Reson. 259, 153–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2015.08.010 (2015).

Stein, R. A., Beth, A. H. & Hustedt, E. J. A Straightforward Approach to the Analysis of Double Electron-Electron Resonance Data. Methods Enzymol. 563, 531–567, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.mie.2015.07.031 (2015).

Fluman, N., Cohen-Karni, D., Weiss, T. & Bibi, E. A Promiscuous Conformational Switch in the Secondary Multidrug Transporter MdfA. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32296–32304, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.050658 (2009).

Cohen, M. R. et al. Overcoming Artificial Broadening in Gd3+-Gd3+ Distance Distributions Arising from Dipolar Pseudo-Secular Terms in DEER Experiments. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 12847–12859, https://doi.org/10.1039/c6cp00829a (2016).

Manukovsky, N., Feintuch, A., Kuprov, I. & Goldfarb, D. Time Domain Simulation of Gd3+-Gd3+ Distance Measurements by EPR. J. Chem. Phys. 147, 044201, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4994084 (2017).

Jeschke, G. MMM: A Toolbox for Integrative Structure Modeling. Protein Sci. 27, 76–85, https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3269 (2018).

Beja, O. & Bibi, E. Functional Expression of Mouse Mdr1 in an Outer Membrane Permeability Mutant of Escherichia Coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 5969–5974 (1996).

Sigal, N., Fluman, N., Siemion, S. & Bibi, E. The Secondary Multidrug/Proton Antiporter MdfA Tolerates Displacements of an Essential Negatively Charged Side Chain. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6966–6971, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M808877200 (2009).

Sigal, N., Lewinson, O., Wolf, S. G. & Bibi, E. E. coli Multidrug Transporter MdfA Is a Monomer. Biochemistry 46, 5200–5208, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi602405w (2007).

Goldfarb, D. et al. HYSCORE and DEER with an Upgraded 95 GHz Pulse EPR Spectrometer. J. Magn. Reson. 194, 8–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2008.05.019 (2008).

Mentink-Vigier, F. et al. Increasing Sensitivity of Pulse EPR Experiments Using Echo Train Detection Schemes. J. Magn. Reson. 236, 117–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2013.08.012 (2013).

Epel, B., Gromov, I., Stoll, S., Schweiger, A. & Goldfarb, D. Spectrometer Manager: A Versatile Control Software for Pulse EPR Spectrometers. Concepts Magn. Reson. B 26B, 36–45, https://doi.org/10.1002/cmr.b.20037 (2005).

Pannier, M., Veit, S., Godt, A., Jeschke, G. & Spiess, H. W. Dead-Time Free Measurement of Dipole-Dipole Interactions between Electron Spins. J. Magn. Reson. 142, 331–340, https://doi.org/10.1006/jmre.1999.1944 (2000).

Kaminker, I. et al. Spectroscopic Selection of Distance Measurements in a Protein Dimer with Mixed Nitroxide and Gd3+ Spin Labels. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 4355–4358, https://doi.org/10.1039/C2CP40219J (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development to E.B. (GIF, Grant Number I-1202-248.9/2012), the Clore Center of Biological Physics at the Weizmann Institute of Science to D.G. and E.B., by a grant from the United States - Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), Jerusalem, Israel to H.S.M. and E.B., and by a grant from the Minerva Foundation to D.G. E.H.Y is the recipient of a Professor Rahamimoff Travel Grant from the United States - Israel Binational Science Foundation. T.B. acknowledges financial support from the Minerva Foundation. The authors would like to thank Dr. Akiva Feintuch for his support with Gd(III) AWG-DEER measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.H.Y. and E.Z. planned, constructed and characterized the mutants. E.H.Y., S.M. and E.Z. prepared and purified double mutants labeled with MTSL. T.B. prepared Gd(III) labeled double mutants (expression, purification, labeling), carried out all W-band DEER measurements and analyzed the data. R.A.S carried out all Q-band DEER measurements and analyzed the data. B.G. and K.L.T. synthesized the Gd-C2 spin label, T.H. wrote the software for simulating distance distributions for the Gd-C2 spin label. E.B., H.S.M. and D.G. conceived and supervised the study. E.H.Y., T.B., E.B., H.S.M. and D.G. wrote the manuscript. All other authors contributed to the writing or proof read the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yardeni, E.H., Bahrenberg, T., Stein, R.A. et al. Probing the solution structure of the E. coli multidrug transporter MdfA using DEER distance measurements with nitroxide and Gd(III) spin labels. Sci Rep 9, 12528 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48694-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48694-0

This article is cited by

-

Structure and mechanism of membrane transporters

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.