Abstract

Euphausia superba (Antarctic krill) is a keystone species in the Southern Ocean, but little is known about how it will respond to climate change. Ocean acidification, caused by sequestration of carbon dioxide into ocean surface waters (pCO2), alters the lipid biochemistry of some organisms. This can have cascading effects up the food chain. In a year-long laboratory experiment adult krill were exposed to ambient seawater pCO2 levels (400 μatm), elevated pCO2 levels mimicking near-future ocean acidification (1000, 1500 and 2000 μatm) and an extreme pCO2 level (4000 μatm). Total lipid mass (mg g−1 DM) of krill was unaffected by near-future pCO2. Fatty acid composition (%) and fatty acid ratios associated with immune responses and cell membrane fluidity were also unaffected by near-future pCO2, apart from an increase in 18:3n-3/18:2n-6 ratios in krill in 1500 μatm pCO2 in winter and spring. Extreme pCO2 had no effect on krill lipid biochemistry during summer. During winter and spring, krill in extreme pCO2 had elevated levels of 18:2n-6 (up to 1.2% increase), 20:4n-6 (up to 0.8% increase), lower 18:3n-3/18:2n-6 and 20:5n-3/20:4n-6 ratios, and showed evidence of increased membrane fluidity (up to three-fold increase in phospholipid/sterol ratios). These results indicate that the lipid biochemistry of adult krill is robust to near-future ocean acidification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Euphausia superba (Antarctic krill, hereafter ‘krill’) is a highly abundant keystone species in the Southern Ocean food web1. Their large biomass and dense swarms make them the primary food source for a range of Antarctic mega-fauna (whales, seals and penguins), fish, squid and seabirds. Krill are lipid-rich and contain high concentrations of nutritious long-chain (≥C20) polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA), particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3)2,3.

Krill are likely to be affected by anthropogenic climate change as ocean warming, sea level rise, sea ice melt and biological invasions increase4. Ocean acidification, caused by sequestration of atmospheric CO2 into ocean surface waters, may be particularly severe in polar marine ecosystems5. As atmospheric CO2 emissions rise, approximately 30% of these emissions are absorbed into seawater at the air/ocean interface6. This increase in seawater pCO2 alters the chemical equilibrium of seawater, causing a decrease in seawater pH7. Average ocean pH has already decreased by 0.1 units since the industrial revolution, and is predicted to decrease by another 0.33 units by the year 2300 if CO2 emissions are not mediated8.

Understanding how species may respond to ocean acidification can be assisted by long-term laboratory experiments which expose organisms to predicted future levels of seawater pCO2. Investigating how animals regulate their physiology in response to environmental changes can be examined through lipid biochemistry. Lipids and their associated fatty acids have a diverse range of roles in the metabolism; they are indicators of an organism’s diet and condition9, and can be used to detect biochemical shifts in response to stress10,11. Triacylglycerol (TAG) lipid classes are used for fat storage, while phospholipids (PL) and sterols (ST) make up the structure of cell membranes12. Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA) such as 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid) and 22:6n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid) are abundant anti-inflammatory fatty acids in PL membranes and conserved for reproductive processes13,14. Arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) is a less abundant but equally important LC-PUFA, being the primary precursor of eicosanoids, which regulate the immune system, reproductive processes, and ion flux15. Elevated ratios of n-6/n-3 PUFA in organisms are indicators of inflammation and physiological stress16,17.

Organisms can also alter their cell membrane fatty acid structure in response to environmental stressors18; a process termed ‘homeoviscous adaptation’. The effects of temperature on homeoviscous adaptation are well known18, but recent studies find that the mechanisms of homeoviscous adaptation can also be applied to other stressors such as pH. Bacteria alter their cell membrane fatty acid saturation and chain length as the pH level (acidity) of their environment changes, which may alter the permeability of the cell membrane and control proton influx19,20,21. The effects of decreasing seawater pH (via ocean acidification), and temperature on homeoviscous adaptation have recently been studied in marine sponges, by measuring ratios of polyunsaturated/saturated fatty acids (PUFA/SFA), ratios of PL/ST, and mean carbon chain length (MCL) in these organisms11. The kinked formation of PUFA increases membrane fluidity, while the absence of double bonds in densely packed SFA increases membrane stability22. Sterols can also be incorporated into cell membranes and packed between PUFA to increase membrane thickness18.

Increased pCO2, or a combination of increased pCO2 and temperature, have a range of effects on the lipid biochemistry of marine organisms: phytoplankton23,24,25,26 sponges11, fish27,28, crustaceans29,30, echinoderms31,32, corals33 and molluscs34.

Ocean acidification may result in a transition from high- to low-lipid phytoplankton and zooplankton species, and this could affect the fitness of higher predators13,35, promoting destabilization of the ecosystem.

Krill lipids have been widely studied due to the importance of krill in the food web3,36,37,38, and commercial interest from the Antarctic krill fishery39,40. A recent study showed that adult Antarctic krill are only affected by severe levels of pCO241, but there is no published information on changes in krill lipid contents and fatty acid composition with elevated pCO2. It is essential to understand whether krill lipid composition will be affected by climate change because the Southern Ocean ecosystem is largely fuelled by lipid energy derived from krill.

Our study aimed to investigate the resilience of adult krill by observing the effects of elevated pCO2 on detailed aspects of krill lipid biochemistry. We reared krill for one year (January–December 2016) in ambient pCO2 levels (400 µatm pCO2), those predicted for the near-future (within the next 100–300 years; 1000, 1500 and 2000 µatm pCO2), and an extreme level of 4000 µatm pCO2. We analysed krill samples to observe whether the total lipid and fatty acid composition of krill changed with pCO2 over this long-term experiment. We also investigated whether lipid indicators of (a) homeoviscous adaptation (PUFA/SFA ratios, PL/ST ratios, and MCL) and (b) immune responses (n-3/n-6; 22:6n-3/20:4n-6 ratios and 18:3n-3/18:2n-6 ratios) in krill were altered by seawater pCO2.

Results

Effect of pCO2 on total lipid and phospholipid/sterol ratios in krill

Quantities of total lipid in krill in weeks 1–5 did not differ between pCO2 treatments or weeks (pCO2; p = 0.577, week; p = 0.097; pCO2*week; p = 0.165). During these first five weeks of the experiment, average quantities of total lipid in krill (Fig. 1A) were 57.4 ± 19.8 mg/g dry mass (DM; mean ± SD). During weeks 26–43 (Fig. 1A), there was a fourfold increase in average total lipid in krill to 273.8 ± 75.4 mg/g DM (mean ± SD), and the effect of pCO2 on total lipid differed between weeks (Two Way ANOVA; pCO2*week, p = 0.052).

(A) Total lipid (mg g−1 dry mass; mean ± SE) and (B) phospholipid/sterol ratio (mean ± SE) of Euphausia superba in weeks 1 (January), 2 (February), 4 (February), 5 (February), 26 (July), 39 (October), 41 (November) and 43 (November) of the one-year ocean acidification experiment. For each pCO2 treatment and week n = 3–7. Statistically significant differences to ambient seawater (400 µatm pCO2) are highlighted with an asterisk (p < 0.05).

Krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 seawater had lower quantities of total lipid than krill in all other pCO2 treatments during week 26 (Tukey p < 0.003). They also had lower total lipid than krill in 400 and 2000 µatm pCO2 during week 41 (Tukey p < 0.046). During weeks 39 and 43, the quantities of total lipid in krill did not differ between pCO2 treatments (p > 0.930).

Ratios of PL/ST in krill (Fig. 1B) did not differ between pCO2 treatments during weeks 1–5 (Two Way ANOVA pCO2*week, p = 0.533). Krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 seawater had higher average PL/ST ratios than krill in 400 µatm pCO2 seawater during weeks 26–43, but these were significantly higher only in weeks 39 (Tukey p < 0.001) and 41 (Tukey p < 0.001).

Principal component analysis of fatty acid percentage composition

Fifty-eight fatty acids were found in krill. Only fatty acids at percentages of ≥0.5% of total fatty acids (17 fatty acids) are analysed and presented in the following results.

Fatty acid percentage data for adult krill collected during weeks 1, 2, 4 and 5 (summer) were similar, and data collected during weeks 26–43 (winter and spring) were similar, so data were combined into these two separate groups for principal component analysis (PCA). Results of PCA analyses for individual weeks can be found in Supplementary Figs S1 and S2.

Fatty acid percentage composition of krill did not differ between pCO2 treatments during weeks 1–5 when analysed using PCA (Fig. 2A). Principal component 1 (PC1) separated krill with higher percentages of LC-PUFA from those with higher percentages of 14:0 and medium-chain (C16–C18) monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and PUFA, but no separation of pCO2 treatments was observed along PC1(x-axis) or principal component 2 (PC2; y-axis).

Principal component analyses of the fatty acid percentage composition of Euphausia superba in 400, 1000, 1500, 2000 and 4000 µatm pCO2 during (A) weeks 1–5 (summer) and (B) weeks 26–43 (winter and spring) of the one-year ocean acidification experiment. The amount of variation (%) explained by each principal component (PC) is shown on the x-axis (PC1) and y-axis (PC2).

Krill fatty acid percentage composition differed between pCO2 treatments during weeks 26–43 (Fig. 2B). PC1 clearly separated krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 seawater from krill in other pCO2 treatments (Fig. 2B). Krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 seawater had higher percentages of LC-PUFA 20:4n-6 and 22:6n-3 than krill in 400–2000 µatm pCO2 seawater. Krill in 400–2000 µatm pCO2 treatments had higher percentages of 14:0, 16:1n-7, 18:3n-3 and 18:4n-3 (Fig. 2B). PC2 separated krill with higher percentages of 14:0 and 16:1n-7 (predominantly krill in 400 µatm pCO2) from those with higher percentages of 18:3n-3 and 18:4n-3 (predominantly krill in 1500 µatm pCO2) and those with higher percentages of 18:2n6, 18:1n9 and 20:5n-3 and 22:6n-3 (predominantly krill in 4000 µatm pCO2). Principal component loadings for each fatty acid included in the PCA analyses are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Percentages (mean ± SD) of the eight fatty acids with the highest PCA loadings (14:0, 16:1n-7, 18:3n-3, 18:4n-3, 18:2n-6, 20:4n-6, 20:5n-3, 22:6n-3) in each pCO2 treatment are shown in Supplementary Table S2 (weeks 1–5; no significant differences, p > 0.05) and Table 1 (weeks 26–43).

Fatty acid indicators of homeoviscous adaptation and immune responses in krill

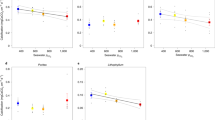

Seawater pCO2 did not affect the MCL, PUFA/SFA ratio, 22:6n-3/20:4n-6 ratio and 18:3n-3/18:2n-6 ratio in krill during weeks 1–5 (Supplementary Table S3), but these ratios were altered during weeks 26–43 (Fig. 3). MCL was higher in krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 than krill in other treatments in week 26 (Two Way ANOVA pCO2*week p = 0.049, Tukey p < 0.05). The PUFA/SFA ratio did not differ between krill in different pCO2 treatments (Two Way ANOVA pCO2*week, p = 0.089; pCO2, p = 0.101). Krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 had a lower 22:6n-3/20:4n-6 ratio than krill in other treatments during weeks 26, 39, 41 and 43 (Two Way ANOVA pCO2*week = 0.571; pCO2, Tukey p < 0.001). Krill in 1500 µatm pCO2 had higher 18:3n-3/18:2n-6 ratios than krill in other treatments (Two Way ANOVA pCO2*week p = 0.100; pCO2 Tukey p < 0.001) and krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 had lower 18:3n-3/18:2n-6 ratios than krill in other treatments during all weeks from 26–43 (ANOVA pCO2*week, p = 0.100; pCO2, Tukey p < 0.05).

Fatty acid indicators of homeoviscous adaptation and immune responses in Euphausia superba exposed to 400, 1000, 1500, 2000 and 4000 µatm pCO2 in experimental weeks 26, 39, 41 and 43, where (A) Mean chain length (MCL); (B) ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids (PUFA/SFA); (C) ratios of docosahexaenoic acid/arachidonic acid (22:6n-3/20:4n-6); (D) alpha-linolenic acid/linoleic acid (18:3n-3/18:2n-6). All values are mean ± SE. For each pCO2 treatment and week, n = 3–5. Statistically significant differences to ambient seawater (400 µatm pCO2) are highlighted with an asterisk (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Krill reared in ambient seawater pCO2 levels (400 µatm pCO2), and those levels predicted for the near-future (100–300 years; 1000–2000 µatm pCO2) did not have significantly different quantities of total lipid (mg g−1 DM) or ratios of PL/ST. We observed no effects of near-future pCO2 on fatty acid composition during weeks 1–5 of the experiment (summer). In winter and spring (weeks 26–43), elevated percentages of C18 fatty acids 18:4n-3 and 18:3n-3 were measured in krill in 400–2000 µatm pCO2 and were highest in krill in 1500 µatm pCO2. Krill in extreme pCO2 (4000 µatm), had a different lipid composition to those in 400–2000 µatm pCO2 treatments during winter and spring. Some krill had lower quantities of total lipid, higher PL/ST ratios and MCL, and all krill had consistently lower ratios of n-3/n-6 fatty acids (22:6n-3/20:4n-6 and 18:3n-3/18:2n-6).

The absence of any pCO2 effect on krill biochemistry during the first five weeks of the experiment suggests that it may take some time before changes can be detected in the lipid profile of adult krill. Numerous short-term ocean acidification studies have, however, detected changes in the lipid and fatty acid profile of other organisms, over time periods substantially shorter than or equal to five weeks23,27,30,34,35. Krill metabolism is controlled by endogeneous rhythms which are cued by seasonal changes in photoperiod, and krill have higher metabolic rates during summer42. A higher metabolic rate may enable krill to more efficiently regulate acid-base balance and other vital functions such as their lipid biochemistry. This could explain why effects of extreme pCO2 on krill biochemistry were not observed during summer, but were most evident in winter (week 26) when metabolic rates are lowest. The interaction between seasonal metabolic rates, lipid biochemistry and increased pCO2 at different time scales is a topic for further study.

Many ocean acidification studies to date have found no effect of near-future pCO2 on total lipid levels in organisms11,31,33,34,43,44,45. Lipids are an important energy source and essential for physiological function and survival, therefore, organisms are likely to maintain relative lipid levels unless they are under substantial physiological stress.

Like other laboratory studies46,47, krill in our study displayed seasonal fluctuations in lipid mass even when given a constant food supply. This occurred in all pCO2 treatments, indicating that endogenous rhythms entrained by the seasonal light cycle were the dominant driver controlling lipid deposition in krill47.

Our finding that near-future pCO2 did not have a significant effect on total lipid mass in adult krill suggests that ocean acidification does not affect their ability to feed or store fat. This corresponds well with a recent study41, which indicates that physiological processes in adult krill are unaffected by near-future acidification. Animals may preferentially retain lipids and utilize protein as an energy source when exposed to near-future pCO243, or maintain lipid and protein levels but grow at a slower rate33. Adult krill in near-future pCO2, however, do not display slow or delayed growth compared with those in ambient seawater41. A previous study found that krill exposed to 750 µatm pCO2 for 24 hours had slightly lower protein content than krill in ambient pCO2 seawater48, suggesting that they may switch from lipid to protein catabolism in high pCO2 conditions.

Near-future pCO2 did not significantly alter the composition of fatty acids associated with immune function (n-3/n-6 ratios) and cell membrane fluidity (MCL, PUFA/SFA and PL/ST) in krill. This is a further indication that these levels of pCO2 do not induce physiological stress. Cell membrane fatty acid composition is tightly regulated by temperature49 and may be driven more by the cold temperatures krill are adapted to14. Ambient seawater temperatures (0.5 °C) were used in this study, which could explain the stability of these fatty acid ratios. Elevated seawater temperatures may influence fatty acid composition more than acidification, although previous studies indicate that krill lipids are not altered by temperatures up to 4 °C above ambient46.

Decreases in total lipid and increases in levels of inflammatory n-6 PUFA in krill reared in 4000 µatm pCO2, suggest that unlike krill in 400–2000 µatm pCO2, these krill were physiologically stressed. Lipid depletion observed during selected weeks in winter and spring corresponds with decreases in quantities of storage lipid (triacylglycerol) in these krill41. Physiological processes such as growth and maturation, along with acid-base regulation required in extreme seawater pCO2, are energetically expensive50 and these processes may have depleted lipid reserves. Feeding in these krill may have also been compromised and caused a decrease in total lipid, although feeding rates were not measured in this study.

Krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 seawater may have been storing 20:4n-6 for production of inflammatory eicosanoids, and for ion transport15,51, in an attempt to regulate immune responses and maintain intra- and extra-cellular pH in this extreme environment. Such increases in n-6 fatty acids have been observed in fish28 and shrimp30 exposed to acidification. Inflammation is important for organism health and tissue repair, but excessive inflammation is maladaptive52.

As levels of n-6 fatty acids in organisms increase, levels of n-3 fatty acids decrease, as the elongation-desaturation pathways for n-3 and n-6 fatty acids compete for the same enzymes53. The lower n-3/n-6 ratios in krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 during winter and spring may, therefore, correspond to a shift in elongation-desaturation pathways used by these krill. The increase in n-3 PUFA in krill up to 1500 µatm pCO2, followed by a decrease down to 4000 µatm pCO2, suggests that 1500 µatm pCO2 may be the point at which krill fatty acid composition switches from an anti-inflammatory status (more n-3 PUFA) to a pro-inflammatory status (more n-6 PUFA).

Cell membrane alteration via homeoviscous adaptation has been most commonly explored with respect to changing temperatures10,54, but other factors such as salinity, hypoxia18, and pH11,21 can alter membrane structure. The higher ratios of PL/ST in krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 in winter and spring suggests that krill may have been actively increasing membrane fluidity, to enable more efficient exchange of ions across their cell membranes and control acid-base balance. Alternatively, the ability of krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 to maintain an optimal ST composition may have been compromised. This could lead to membrane ‘hyper-fluidity’ and disrupt cellular function11. Under hypercapnic stress, homeoviscous adaptation through regulation of lipid class ratios (e.g. PL/ST) may be more energy efficient than modification of PUFA/SFA ratios and MCL, which remained more stable in krill in 4000 µatm pCO2.

The fatty acid profile of krill in our laboratory study also reflects their aquarium diet and does differ to that of wild krill. Ratios of 22:6n-3/20:4n-6, 20:5n-3/22:6n-3, and 18:3n-3/18:2n-6 are higher in wild krill3,36 than were observed for our laboratory reared krill, indicating that wild krill have higher n-3/n-6 ratios. The diet of wild krill is not replicable in the laboratory55, but the higher n-3/n-6 ratios of these krill may influence and even further enhance their resilience to elevated pCO2, due to their higher levels of anti-inflammatory fatty acids. Levels of krill prey in the Southern Ocean also fluctuate spatially and temporally37, and krill in our study were fed a constant supply of food. Krill increase their feeding rates when exposed to high pCO248, possibly to maintain enough energy for physiological processes under pCO2 stress41,48. Changing food levels both seasonally, regionally and with climate change may, therefore, also influence how wild krill respond to ocean acidification.

Krill will be exposed to multiple climate change stressors in the future, in addition to ocean acidification4. Rapid warming is already evident in the West Antarctic Peninsula region56, both at the sea surface57, and in the deep ocean (Antarctic Bottom Water58). In laboratory studies, simulated ocean warming significantly affects the fatty acid composition of some organisms11,26,29,59. A previous long-term laboratory study found only minor differences between the lipid and fatty acid composition of krill reared in −1 °C, 1 °C and 3 °C46. The temperature range used in this study was within the range that krill experience in their natural environment (krill are abundant at South Georgia where seawater temperatures reach 5 °C37), therefore, the temperatures may not have been high enough to detect significant temperature effects. Further studies are needed to establish whether the combined effects of increased seawater temperature and pCO2 affect the lipid and fatty acid composition of krill.

Conclusions

Lipid mass and fatty acid composition in adult krill were unaffected when krill were exposed to near-future levels of pCO2 (1000–2000 µatm) in the laboratory. Extreme pCO2 altered the lipid and fatty acid content and composition of krill, although consistent differences were not observed across all experimental weeks. Extreme pCO2 had no effect on krill lipid biochemistry during summer, but during selected weeks in winter and spring, krill in 4000 µatm pCO2 had elevated levels of inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids and showed evidence of increased membrane fluidity. These observations suggest that krill may be less able to tolerate elevated pCO2 conditions during winter and spring, when metabolic rates are lower and reproductive maturation occurs. Seawater pH levels are also lower in the Antarctic in the winter than summer60, and prey availability is lower in winter in some areas of the Southern Ocean37. Collectively, these factors may influence how krill respond to near-future pCO2 in the wild, and determine their resilience in a future high CO2 world.

Methods

Experimental conditions

Experimental conditions are described in detail in a previous manuscript41. Briefly, krill were collected from the Southern Ocean (66–03°S, 59–25°E and 66–33°S, 59–35°E) on the research and supply vessel (RSV) Aurora Australis, using a mid-water trawl net (sampled within the top 100 m of the water column). They were held in shipboard aquaria using standard husbandry methods61, and transported to the Australian Antarctic Division Krill Aquarium in Tasmania.

For ocean acidification experiments, five 300 L tanks were equilibrated to five pCO2 levels; 400 μatm pCO2 (pH 8.1 control treatment), 1000 μatm pCO2 (pH 7.8), 1500 μatm pCO2 (pH 7.6), 2000 μatm pCO2 (pH 7.4) and 4000 μatm pCO2 (pH 7.1). Seawater temperature of all tanks was held at 0.5 °C (±0.2). Seawater chemistry for the duration of the experiment is reported in the supplementary material of a previous manuscript41. Observational units (CO2 treatment tanks) could not be replicated, due to the large tank size required to achieve the best possible animal husbandry for this pelagic species, and the limited space and resources available for these large tanks over such a long-term study. Tanks were inspected daily, and there was no visual evidence to suggest that tank effects were confounding our experimental results.

Two hundred krill were randomly assigned to each tank on the first day of the experiment (25th January 2016), and reared in these pCO2 treatments until the experiment ended on the 12th December 2016. Light was controlled in the laboratory to mimic the seasonal Southern Ocean light regime (66°S, 30 m depth) and krill were fed six days per week with a mixed microalgal diet of the Antarctic species Pyramimonas gelidicola (2 × 104 cells mL−1), and Reed Mariculture Inc. (USA) cultures of Thalassiosira weissflogii (8.8 × 103 cells mL−1), Pavlova lutheri (4.5 × 104 cells mL−1) and Isochryisis galbana (5.5 × 10 cells mL−1).

Sample collection and lipid extraction

Krill were sampled from the pCO2 treatment tanks in experimental weeks 1, 2, 4 and 5 (summer), 26 (winter), and 39, 41 and 43 (spring). Five to ten krill were sampled from each tank during each sampling week (only three krill were sampled from the 4000 μatm pCO2 tank due to increased mortality in that tank and lower overall numbers of krill41). Individual krill were placed in cryo-tubes and frozen immediately at −80 °C until needed for lipid analysis.

Krill were weighed (wet mass), and the length of each specimen was measured from the tip of the rostrum to the tip of the uropod using measurement ‘Standard Length 1’62. To prevent sample degradation, krill were kept frozen during the measuring process. A dry mass (g) for each krill sample was obtained by multiplying the wet mass by 0.2278 to account for the 77.2% water content in krill2.

Krill specimens were added to separatory funnels and extracted using a modified Bligh and Dyer method63, consisting of a methanol:dichloromethane:water (MeOH:CH2Cl2:H2O) solvent mixture (20:10:7 mL), and overnight extraction. Phase separation was carried out the following day by adding 10 mL CH2Cl2 and 10 mL saline MilliQ H2O to each separatory funnel, giving a final MeOH:CH2Cl2:H2O solvent ratio of 1:1:0.85. The lower layer was drained into a round bottomed flask, and the total solvent extract was concentrated using rotary evaporation. The concentrated extract was transferred into a pre-weighed 2 mL vial and the solvent was blown down under nitrogen (N2) gas to obtain a total lipid extract (TLE) weight. Solvent (CH2Cl2) was added until further procedures were carried out to avoid oxidation.

Lipid class analysis

TLE were used to obtain the lipid class composition of each sample. Aliquots (1 μl) of each TLE were spotted on chromarods and developed in a solvent bath of hexane:diethyl-ether:acetic acid (90:10:0.1 mL, v-v:v) for 25 min, before drying in an oven at 50 °C for 10 min. Chromarods were placed in an Iatroscan MK-5 TLC/FID analyser (Iatron Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) for analysis. A standard solution of known quantities of wax esters (WE), triacylglycerols (TAG), free fatty acids (FFA), sterols (ST), and phospholipids (PL) was used to confirm peak identities and to calibrate the flame ionisation detector. Lipid class peaks were labelled using SIC-480II Iatroscan Integrating Software v.7.0-E, quantified using predetermined linear regressions, and expressed as mg per g of krill dry mass (mg g DM−1). Triacylglycerol data is presented in an earlier manuscript41. Only the PL to ST ratio is presented in this manuscript as we were primarily interested in investigating homeoviscous adaptation in krill.

Fatty acid analysis

To prepare fatty acid methyl esters (FAME), a subsample of the TLE was transferred to a glass test tube fitted with a Teflon lined screw cap, and treated with 3 mL methylating solution (MeOH: CH2Cl2: HCl (hydrochloric acid), 10:1:1, v-v:v). The sample was then heated at 90–100 °C for 1 hr 15 mins. Samples were cooled and 1 mL of H2O and 1.8 mL of C6H14 (hexane): CH2Cl2 solution was added to extract the FAME. Samples were then centrifuged for five minutes at 3000 rpm, and the upper layer containing FAME was transferred to a vial. An additional 1.8 mL of C6H14:CH2Cl2 was added to the test tube and samples were centrifuged again. This process was repeated three times in total, and samples were blown down using N2 gas in between transfers. FAME samples were made up to 1.5 mL with CH2Cl2 and stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Prior to analysis, samples were blown down again using N2 gas and 1.5 mL of internal injection standard (23:0 FAME) was added to each vial.

Samples were analysed via gas chromatography (GC-FID) using an Agilent Technologies 7890 A GC System (Palo Alto, California USA) equipped with a non-polar Equity™−1 fused silica capillary column (15 m × 0.1 mm internal diameter and 0.1 µm film thickness). Samples (0.2 µl) were injected in splitless mode at an oven temperature of 120 °C with helium as the carrier gas. The oven temperature was raised to 270 °C at a rate of 10 °C per minute, then to 310 °C at 5 °C per minute. Agilent Technologies ChemStation software was used to quantify fatty acid peaks, with initial identification based on comparison of retention times with known (Nu Chek Prep mix) and laboratory (fully characterised tuna oil) standards. Fatty acid peaks were expressed as a percentage of the total fatty acid area. Fatty acid quantities (in mg g−1 DM and mg g−1 lipid) were calculated using the internal injection standard (C23:0) of known concentration.

Confirmation of component identification was performed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) of selected samples and was carried out on a ThermoScientific 1310 GC coupled with a TSQ triple quadruple. Samples were injected using a Tripleplus RSH auto sampler using a non polar HP-5 Ultra 2 bonded-phase column (50 m × 0.32 mm i.d. × 0.17 µm film thickness). The HP-5 column was of similar polarity to the column used for GC analyses. The initial oven temperature of 45 °C was held for 1 min, followed by an increase in temperature of 30 °C per minute to 140 °C, then at 3 °C per minute to 310 °C, where it was held for 12 minutes. Helium (He) was used as the carrier gas. The operating conditions of the GC-MS were: electron impact energy 70 eV; emission current 250 µamp, transfer line 310 °C; source temperature 240 °C; scan rate 0.8 scan/sec and mass range 40–650 Da. Thermo Scientific XcaliburTM software (Waltham, MA, USA) was used to process and acquire mass spectra.

Mean fatty acid chain length (MCL) was calculated using the equation from reference11:

Statistical analyses

Principal component analyses (PCA) were carried out in PRIMER 6 (http://www.primer-e.com). Pearson correlation was used due to differences in fatty acid variances, and data were transformed (log x + 1) before analysis. All other statistical analyses were carried out in RStudio (v 1.1.453; www.rstudio.com). Total lipid, specific fatty acids, lipid class and fatty acid ratios were analysed using Two Way ANOVA with pCO2 and week as main effects, and a pCO2*week interaction term. Tukey comparisons or Dunnett’s tests were used to compare levels of pCO2 with one another. On visual assessment of the data, weeks 1–5 were analysed as a group, and weeks 26–43 were analysed as a separate group, as the groups had heterogeneous variances and represented two distinct data sets. Type 3 Sums of Squares were used as the sampling regime was unbalanced. Data were visualised using Q-Q plots and residuals versus fitted values plots, to verify that they met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances. Log or square root transformations were applied when assumptions of normality and/or homogeneity of variances were not met. For Two Way ANOVA of total lipid data, one outlier was removed from the statistical analysis in order to meet assumptions of homogeneity of variances. All tests were two tailed with α = 0.05.

Principal component figures were created in PRIMER 6, and all other figures were created using the RStudio packages ggplot2, plyr and dplyr.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Trathan, P. N. & Hill, S. L. The importance of krill predation in the Southern Ocean. In Biology and Ecology of Antarctic Krill (ed. Siegel, V.) 441 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Virtue, P., Nichols, P. D., Nicol, S., McMinn, A. & Sikes, E. L. The lipid composition of Euphausia superba Dana in relation to the nutritional value of Phaeocystis pouchetii (Hariot) Lagerheim. Antarct. Sci. 5, 169–177 (1993).

Ericson, J. A. et al. Seasonal and interannual variations in the fatty acid composition of adult Euphausia superba Dana, 1850 (Euphausiacea) samples derived from the Scotia Sea krill fishery. J. Crustac. Biol. 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcbiol/ruy032 (2018).

Rintoul, S. R. et al. Choosing the future of Antarctica. Nature 558, 233–241 (2018).

Fabry, V. J., McClintock, J. B., Mathis, J. T. & J.M., G. Ocean acidification at high latitudes: the bellweather. Oceanography 22, 160–171 (2009).

Doney, S. C., Fabry, V. J., Feely, R. A. & Kleypas, J. A. Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 1, 169–192 (2009).

Raven, J. et al. Ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide. (The Royal Society, 2005).

Ciais, P. et al. Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2013).

Dalsgaard, J., St John, M., Kattner, G., Muller-Navarra, D. & Hagen, W. Fatty acid trophic markers in the pelagic marine environment. Adv. Mar. Biol. 46, 225–340 (2003).

Hixson, S. & Arts, M. Climate warming is predicted to reduce omega-3, long-chain, polunsaturated fatty acid production in phytoplankton. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 2744–2755 (2016).

Bennett, H., Bell, J., Davy, S., Webster, N. & Francis, D. Elucidating the sponge stress response; lipids and fatty acids can facilitate survival under future climate scenarios. Glob. Chang. Biol., https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14116 (2018).

Parrish, C. et al. Lipid and phenolic biomarkers in marine ecosystems: analysis and applications. In The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry Vol. 5 Part D Marine Chemistry 193–223 (Springer-Verlag, 2000).

Kattner, G. et al. Perspectives on marine zooplankton lipids. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 64, 1628–1639 (2007).

Corsolini, S. & Borghesi, N. A comparative assessment of fatty acids in Antarctic organisms from the Ross Sea: Occurence and distribution. Chemosphere 174, 747–753 (2017).

Stanley-Samuelson, D. Physiological roles of prostaglandins and other eicosanoids in invertebrates. Biol. Bull. 173, 92–109 (1987).

Calder, P. & Grimble, R. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation and immunity. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 56, S14–S19 (2002).

Van Anholt, R. Dietary fatty acids and the stress response of fish: arachidonic acid in seabream and tilapia. PhD Thesis. (Radboud University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2004).

Ernst, R., Ejsing, C. & Antonny, B. Homeoviscous adaptation and the regulation of membrane lipids. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 4776–4791 (2016).

Bajerski, F., Wagner, D. & Mangelsdorf, K. Cell membrane fatty acid composition of Chryseobacterium frigidisoli PB4T, isolated from Antarctic glacier forefield soils, in response to changing temperature and pH conditions. Front. Microbiol. 8, 677 (2017).

Siliakus, M. F., van der Oost, J. & Kengen, S. W. M. Adaptations of archael and bacterial membranes to variations in temperature, pH and pressure. Extremophiles 21, 651–670 (2017).

Sohlenkamp, C. Membrane homeostasis in bacteria upon pH challenge. In Biogenesis of Fatty Acids, Lipids and Membranes (ed. Geiger, O.) 1–13 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Nelson, D. L. & Cox, M. M. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. (W.H. Freeman and Company, 2012).

Wynn-Edwards, C. et al. Species-specific variations in the nutritional quality of Southern Ocean phytoplankton in response to elevated pCO2. Water 6 (2014).

Bermúdez, R. et al. Long-term conditioning to elevated pCO2 and warming influences the fatty and amino acid composition of the diatom Cylindrotheca fusiformis. PLoS One 10, e0123945 (2015).

King, A. et al. Effects of CO2 on growth rate, C:N:P, and fatty acid composition of seven marine phytoplankton species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 537, 59–69 (2015).

Bi, R., Ismar, S., Sommer, U. & Zhao, M. Simultaneous shifts in elemental stoichiometry and fatty acids of Emiliana huxleyi in response to environmental changes. Biogeosciences 15, 1029–1045 (2018).

Díaz-Gil, C., Catalán, I., Palmer, M., Faulk, C. & Fuiman, L. Ocean acidification increases fatty acids levels of larval fish. Biol. Lett. 11, 20150331 (2015).

Murray, C., Fuimann, L. & Baumann, H. Consequences of elevated CO2 exposure across multiple life stages in a coastal forage fish. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 74, 1051–1061 (2017).

Garzke, J., Hansen, T., Ismar, S. & Sommer, U. Combined effects of ocean warming and acidification on copepod abundance, body size and fatty acid content. PLoS One 11, e0155952 (2016).

Gao, Y. et al. The immune-related fatty acids are responsive to CO2 driven seawater acidification in a crustacean brine shrimp Artemia sinica. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 81, 342–347 (2018).

Matson, P., Yu, P., Sewell, M. & Hofmann, G. Development under elevated pCO2 conditions does not affect lipid utilization and protein content in early life-history stages of the purple sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Biol. Bull. 223, 312–327 (2012).

Verkaik, K., Hamel, J.-F. & Mercier, A. Carry-over effects of ocean acidification in a cold-water lecithotrophic holothuroid. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 557, 189–206 (2016).

Strahl, J., Francis, D., Doyle, J., Humphrey, C. & Fabricius, K. Biochemical responses to ocean acidification contrast between tropical corals with high and low abundances at volcanic carbon dioxide seeps. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, 897–909 (2016).

Valles-Regino, R. et al. Ocean warming and CO2-induced acidification impact the lipid content of a marine predatory gastropod. Mar. Drugs 13, 6019–6037 (2015).

Rossoll, D. et al. Ocean acidification-induced food quality deterioration constrains trophic transfer. PLoS One 7, e34737 (2012).

Hagen, W., Kattner, G., Terbruggen, A. & Van Vleet, E. S. Lipid metabolism of the Antarctic krill Euphausia superba and its ecological implications. Mar. Biol. 139, 95–104 (2001).

Schmidt, K. & Atkinson, A. Feeding and food processing in Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba Dana). In Biology and Ecology of Antarctic Krill (ed. Siegel, V.) 175–224 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Hellessey, N. et al. Seasonal and interannual variation in the lipid content and composition of Euphausia superba Dana 1850 (Euphausiacea) samples derived from the Scotia Sea fishery. J. Crustac. Biol. 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcbiol/ruy053 (2018).

Gigliotti, J. C., Davenport, M. P., Beamer, S. K., Tou, J. C. & Jaczynski, J. Extraction and characterisation of lipids from Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba). Food Chem. 125, 1028–1036 (2011).

Nicol, S., Foster, J. & Kawaguchi, S. The fishery for Antarctic krill - recent developments. Fish Fish. 13, 30–40 (2012).

Ericson, J. A. et al. Adult Antarctic krill proves resilient in a simulated high CO2 ocean. Commun. Biol., https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-018-0195-3 (2018).

Meyer, B. & Teschke, M. Physiology of Euphausia superba. In Biology and Ecology of Antarctic Krill (ed. Siegel, V.) 145–174 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Carter, H. A., Ceballos-Osuna, L., Miller, N. A. & Stillman, J. H. Impact of ocean acidification on metabolism and energetics during early life stages of the intertidal porcelain crab Petrolisthes cinctipes. J. Exp. Biol. 216, 1412–1422 (2013).

Rivest, E. B. & Hofmann, G. E. Effects of temperature and pCO2 on lipid use and biological parameters of planulae of Pocillopora damicornis. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 473, 43–52 (2015).

Ab Lah, R., Kelaher, B. P., Bucher, D. & Benkendorff, K. Ocean warming and acidification affect the nutritional quality of the commercially-harvested turbinid snail Turbo militaris. Mar. Environ. Res. 141, 100–108 (2018).

Brown, M. Growth, Maturation and Physiology of Antarctic Krill. PhD Thesis. (Institute of Antarctic and Southern Ocean Studies, University of Tasmania, 2010).

Höring, F., Teschke, M., Suberg, L., Kawaguchi, S. S. & Meyer, B. Light regime affects the seasonal cycle of Antarctic krill: Impacts on growth, feeding, lipid metabolism and maturity. Can. J. Zool., https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2017-0353 (2018).

Saba, G. K., Schofield, O., Torres, J. J., Ombres, E. H. & Steinberg, D. K. Increased feeding and nutrient excretion of adult Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, exposed to enhanced carbon dioxide (CO2). PLoS One 7, e52224 (2012).

Los, D. A. & Murata, N. Membrane fluidity and its roles in the perception of environmental signals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 1666, 142–157 (2004).

Whiteley, N. M. Physiological and ecological responses of crustaceans to ocean acidification. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 430, 257–271 (2011).

Rowley, A., Vogan, C., Taylor, G. & Clare, A. Prostaglandins in non-insectan invertebrates: recent insights and unsolved problems. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 3–14 (2005).

Calder, C. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes. Nutrients 2, 355–374 (2010).

Monroig, Ó. & Kabeya, N. Desaturases and elongases involved in polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in aquatic invertebrates: a comprehensive review. Fish. Sci. 84, 911–928 (2018).

Hazel, J. Thermal adaptation in biological membranes: is homeoviscous adaptation the explanation? Annu. Rev. Physiol. 57, 19–42 (1995).

Brown, M., Kawaguchi, S., Candy, S. & Virtue, P. Temperature effects on the growth and maturation of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba). Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 57, 672–682 (2010).

Vaughan, D. et al. Recent rapid climate warming on the Antarctic Peninsula. Clim. Change 60, 243–274 (2003).

Meredith, M. P. & King, J. C. Rapid climate change in the ocean west of the Antarctic Peninsula during the second half of the 20th century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32 (2005).

Schmidtko, S., Heywood, K. J., Thompson, A. F. & Aoki, S. Multidecadal warming of Antarctic waters. Science 346, 1227–1231 (2014).

Malekar, V. C. et al. Effect of elevated temperature on membrane lipid saturation in Antarctic notothenioid fish. PeerJ 2018 (2018).

McNeil, B. I. & Matear, R. J. Southern Ocean acidification: a tipping point at 450-ppm atmospheric CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18860–18864 (2008).

King, R., Nicol, S., Cramp, P. & Swadling, K. Krill maintenance and experimentation at the australian antarctic division. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 36, 271–283 (2003).

Kirkwood, J. M. A guide to the Euphausiacea of the Southern Ocean. ANARE Research Notes 1 (Antarctic Division Department of Science and Technology, 1984).

Bligh, E. G. & Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 (1959).

Acknowledgements

We thank Tasha Waller, Ashley Cooper, Blair Smith and Rob King for their invaluable technical assistance in the krill aquarium, and Guang Yang for assistance with daily experimental monitoring. The helpful comments of two anonymous reviewers and the editor are acknowledged and assisted in improving the manuscript. This research was funded by an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant LP140100412 between the Australian Antarctic Division, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (University of Tasmania), Aker Biomarine and Griffith University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to experimental design. J.A.E. completed all experimental work and statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. N.H. assisted with experimental monitoring and lipid analyses. N.H., S.K., P.D.N., S.N., N. Hoem and P.V. assisted with manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ericson, J.A., Hellessey, N., Kawaguchi, S. et al. Near-future ocean acidification does not alter the lipid content and fatty acid composition of adult Antarctic krill. Sci Rep 9, 12375 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48665-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48665-5

This article is cited by

-

Temperature increase alters relative fatty acid composition and has negative effects on reproductive output of the benthic copepod Tachidius discipes (copepoda: Harpacticoida)

Marine Biology (2024)

-

Climate change impacts on Antarctic krill behaviour and population dynamics

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.