Abstract

Herein, the optoelectrical investigation of cadmium zinc telluride (CZT) and indium (In) doped CZT (InCZT) single crystals-based photodetectors have been demonstrated. The grown crystals were configured into photodetector devices and recorded the current-voltage (I-V) and current-time (I-t) characteristics under different illumination intensities. It has been observed that the photocurrent generation mechanism in both photodetector devices is dominantly driven by a photogating effect. The CZT photodetector exhibits stable and reversible device performances to 632 nm light, including a promotable responsivity of 0.38 AW−1, a high photoswitch ratio of 152, specific detectivity of 6.30 × 1011 Jones, and fast switching time (rise time of 210 ms and decay time of 150 ms). When doped with In, the responsivity of device increases to 0.50 AW−1, photoswitch ratio decrease to 10, specific detectivity decrease to 1.80 × 1011 Jones, rise time decrease to 140 ms and decay time increase to 200 ms. Moreover, these devices show a very high external quantum efficiency of 200% for CZT and 250% for InCZT. These results demonstrate that the CZT based crystals have great potential for visible light photodetector applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cadmium zinc telluride (CdZnTe or CZT), a p-type semiconductor have recently gained much attention in the key detector technologies. The main attractive aspect of CZT crystals are (i) wide band gap (~1.68 eV) which is necessary for room temperature operation, (ii) a large photon absorption cross section (∼104 cm2/g for 1 keV photon energy; for photon energy <50 keV the absorption efficiency is >95%) for efficient conversion of optical energy in to electrical energy, and (iii) high resistivity (1010 Ω.cm) to minimize the noise due to limiting the leakage current1,2,3,4,5. These specific properties allow its applications in a wide range of devices such as X-ray or γ-ray detector, nuclear spectroscopy, medical imaging, radiation sensors, photorefractive, etc.6,7,8,9,10. Due to such venerable applications of CZT crystals in detector technology, it has already started to replace the existing X-ray and γ-ray detectors as well as other semiconductors detectors.

However, there are few drawbacks associated with CZT crystals. Firstly, it has relatively high concentrations of impurities and inherent defects that cause small drift length11,12. Secondly, low hole mobility, which caused by the trapping of charge carries13. These downside causes the poor device performance and hence limiting the applications of CZT crystals. Therefore it is essential to compensate these impurities and defects with the introduction of additional donor impurity into the CZT crystals. The additional donor impurity accomplishes a balance between electron and hole concentration and compensate the native defects presents into the CZT crystals14. Indium is considered one of the most promising dopants for CZT crystals in a doping concentration range of 1 × 1019 at./cm3 to 8 × 1019 at./cm3 15.

Recently, silicon and germanium based photodetectors have been widely studied16,17,18,19, but their relatively low external quantum efficiency (EQE), poor responsivity, high dark currents and long response time limit the commercialization of these devices. Most recently, photodetectors based on lead dihalide (LDH)and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMD) have shown promising results but they suffer from environmental instability due to oxygen chemisorption effect20,21,22,23,24. Photodetectors based on PbI2 and PbFI, reported by Tan et al. showed higher photocurrent in a vacuum than those in air25. Similar results were also observed for ternary Ta2NiSe5 based photodetector where photocurrent in vacuum was larger than that in ambient26. Huo and co-workers observed responsivity of 18.8 m A W−1 in vacuum for the tungsten disulfide multilayer based photodetector, which is drastically reduced in the air to 0.2 μA W−1 27. Another study on molybdenum disulfide based phototransistor showed a maximum responsivity of 2200 A W−1 in a vacuum, which was reduced to 780 A W−1 in air28. These studies urges to find an alternate material for a photodetector which is highly efficient as well as have good environmental stability. As discussed above, the CZT owing good optoelectrical properties for radiation detectors, as well as have good environmental stability. Therefore, it is expected that it can also deliver good performance in visible photodetector technology.

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic study on CZT and InCZT based photodetector have been reported so far. In the present work, we have grown the pure and indium doped CZT single crystals and demonstrates the photocurrent generation mechanism in photodetectors based on these crystals. For this, we have measured the illumination dependence current-voltage (I-V) and current-time (I-t) curves and calculated the detectivity, responsivity, EQE, photoconductivity and switching time of photodetectors.

Experimental Details

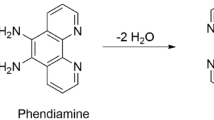

The cut and polished rectangular specimens from grown crystals6,12 were prepared and subjected to X-ray diffractometer (XRD) to confirm the growth direction. A typical photodetector consists of a semiconductor as a channel, with two ohmic contacts affixed to opposite ends of the channel as depicted in Fig. 1(a). For the fabrication of devices, a pair of Au electrodes (~20 nm thick) with 200 μm apart was evaporated by the sputtering unit on the grown rectangular crystals. These electrodes serve as source and drain electrodes for the photodetector device. Gold has a work function of ∼5.0 eV, closely match to the work function of CZT (4.6 eV), which make it a good choice for the injection/collection of charge carriers at the source/drain electrodes29. The performance of the fabricated photodetector devices was analyzed in an optical cryostat (Oxford optistat DN2) under the evacuation of ~10−4 Torr. Programmable digital electrometer (Keithley 6517b) along with an ammeter was used to measure the I-V characteristics of devices. A tungsten lamp linked with a power variance was used to attain the preferred illumination. The whole experimental display is exposed in scheme-I (see Supplementary Data). The effect of light intensity on transient photoconductivity was studied by using the previous circuit shown in scheme-I (see Supplementary Data). The photocurrent as a function of time was measured using the programmable digital electrometer interface with software package 6517 Hi-R Step Response. The rise and decay photocurrent were extracted by subtracting the dark current from the total measured current. The illumination and darkness time were controlled via SR540 digital chopper controller. Hall effect measurement at 300 K was studied on samples by applying the voltage of 10 Volt under the magnetic field of 3700 gauss. The value of the carrier concentration was determined by calculating the value of the Hall coefficient. Hall mobility was calculated by using the values of electrical conductivity and Hall coefficient30. The carrier life time was calculated by transient photoconductivity measurements as reported in previous paper31.

Results and Discussion

XRD patterns of CZT and InCZT rectangular crystals specimens (inset of figures) are displayed in Fig. 2(a,b), respectively. Both patterns display only a single diffraction peak observed at an angle ~24.463° (d = 3.63580 Å) for CZT and 24.230° (d = 3.67021) for InCZT. The observed XRD peaks in both specimens correspond to the cubic crystal system of space group F-43mE (216) and crystals were grown in the direction of (111) plane, confirmed from standard JCPDS# 50–1438.

The energy band diagram for both CZT and InCZT crystals are shown in Fig. 1(b,c), respectively. The band gap of \(C{d}_{1-x}Z{n}_{x}Te\) (CZT) crystal vary from 1.53 eV to 1.65 eV depending upon the value of x according to the relation8:

With x = 0.1 in the present work, the band gap of CZT was calculated to be ∼1.572 eV. Takahashi and Watanabe have reported the ionization potential of CZT crystal ∼4.6 eV32, which leads to the conduction band edge at −3.03 eV and valance band gap edge −4.6 eV as shown in Fig. 1(b,c). The In-doping in CZT create shallow donor levels at 14 meV below the conduction band edge33, as shown in Fig. 1c.

Figure 3(a,b) shows the I-V characteristics of CZT and InCZT based photodetector devices under different power density of laser of 632.8 nm. It is observed from Fig. 3(a) that the dark current Id, for pure CZT photodetector is very small of the order of 1.38 nA, which is good for high-performance photodetectors34,35. On the other hand, In-doping provides additional free carriers which results in a higher dark current of 25 nA for InCZT photodetector. Under the illumination with laser light, electron-hole pairs generated, results in increase of device current as shown in Fig. 3(a,b). It is also visible from Fig. 3(a,b) that after reaching a specific applied bias the current achieved its saturation value and does not further increase with the increase of applied bias. This is because all the photogenerated carriers start moving for this applied bias and participate in photocurrent. There are no free carriers left to participate in current beyond this applied bias. The electrical parameters calculated from Hall effect measurements at room temperature found to be a mobility of μCZT = 1.57 × 102 cm2/V.s and carrier concentration nf = 1.72 × 1011cm−3 for CZT crystal. The InCZT crystal show slightly Improved carrier mobility of μInCZT = 2.34 × 102 cm2/V.s might be due to slightly higher carrier concentration of nf = 2.38 × 1011cm−3. Moreover, the carrier life time in CZT crystal was found to be 7.61 × 10−2 s while a longer life time was measured in InCZT of 9.83 × 10−2 s. The longer life time may be another reason for the improved carrier mobility in InCZT crystal.

Figure 4(a–c) shows the dependency of responsivity (R), external quantum efficiency and detectivity (D*) on incident illumination power density. These three parameters are very important for the evaluation of the sensitivity of photodetector. Responsivity is defined as the ratio of photocurrent generated \(({I}_{p}={I}_{ph}-{I}_{dark})\) to the incident irradiation power (Pin) on the effective area (A) of a photodetector35,36,37:

As it is displayed by Fig. 4(a), the CZT based photodetector exhibits a responsivity of 0.37 AW−1 at illumination intensity of 0.049 mWcm−2 which decreases with the increase of illumination intensity. For the InCZT detector, the responsivity increase to 0.50 AW−1 for the same illumination and follow the identical pattern as CZT detector while remains higher responsivity for all illumination power density. The measured responsivity for our devices are larger than the previously reported values for PbI2 of 1 × 10−4 A W−1 34, MoS2 of 7.5 × 10−3 A W−1 38 and WS2 of 9.2 × 10−5 A W−1 39.

The most important figures of merit for a photodetector is specific detectivity (D*), reflects the photodetectors sensitivity. Specific detectivity was calculated by relation35,36,37:

As shown in Fig. 4(b), the highest measured D* for pure CZT photodetector are calculated to be 6.00 × 1011 Jones at 5V bias. Doping of indium decreases the detectivity to 1.50 × 1011 Jones. As discussed above, the In-doping introduce a trap level below the conduction band in InCZT crystal. The presence of these trap states in the band gap of semiconductor act as the trapping and recombination center for the photogenerated charge carriers. Therefore, InCZT detector need slightly higher power to detect the input signal which results in lower detectivity as compare to pure CZT crystal.

The third figure of merit of a photodetector is EQE which was calculated by the equation35,36,37,40:

Where λ is illumination wavelength, c is speed of light, h is Planck constant and e is the electronic charge. It is observed by Fig. 4(c) that the highest calculated EQE of CZT based photodetector is 200% at 0.049 mWcm−2 illuminations and decreases with the increase of illumination intensity. For the InCZT based device, EQE increases to 250% and remains higher than the pure CZT based photodetector for all intensity. EQE also remains more than 100% for all illumination (except under the 1 mWcm−2 illumination of CZT photodetector). The measured EQE is higher than most of the previously reported devices such as PbI2 single crystal photodetector 49.6%41, MEH-PPV + CdS(Se) quantum dots of 60%42, CuPC/PTCBI of 75%43, PbS quantum dots + PCBM + P3HT of 51%44. The comparison of the key parameters of reported photodetectors with the present work are summarized in Table 1.

The switching behavior of pure and In-doped CZT photodetector devices are shown in Fig. 5(a,b), respectively. The time-dependent photocurrent of the photodetector was obtained by periodically turning ON/OFF the laser for different illumination intensity at 5V. When laser turned “ON” the current quickly increases to a saturation value and rapidly decreases when turned “OFF” and again attain the dark values (1.38 nA for CZT and 25 nA for InCZT). The corresponding rise and decay times are listed in Table 2. Rise time (tr) is defined as the time required to surge the photocurrent from 10% to 90% of saturation value while the decay time (td) is the time required to fall its output from 90% to 10% of final output level45. It is observed from Table 2 that rise time for CZT based detector are in the range of 200–290 ms while decay time are in the range of 150 to 240 ms. For the InCZT based photodetector, the rise time decreases (in the range of 140–250 ms) and decay time increases (in the range of 200–280 ms). The decrease in rise time and increase in decay time for InCZT based detector can be understood in terms of decrease in resistivity or increase in conductivity of InCZT as compare to pure CZT [Fig. 6(b)]. Due to higher conductivity in InCZT, it is easy to start motion of charge carriers (decrease of rise time) when the laser is turned ON and difficult to stop the carriers when laser is turned OFF (an increase of decay time). In order to study the stability of the photodetectors, the laser was switched periodically at a constant interval for multiple cycles. The stability is good after five cycles which shows the robustness and reproducibility of the photodetector. As shown in Fig. 5, the ON/OFF switching behavior retained very well and reversible. The current in CZT photodetector rapidly increased from 1.38 nA to 209 nA as the laser turn on, giving a high photoswitch ratio (Ilight/Idark) of 152. The InCZT based photodetector showed a much lower photoswitch ratio ≈10 with a relatively high dark current of 25 nA.

The different device performance of CZT and InCZT based photodetectors make it keen to further investigate their photocurrent generation mechanism. Various detection mechanisms have been reported, out of them photoconductive effect and photogating effect are the most commonly observed in photodetector devices28,46,47. The photoconductive effect involves a process in which photon absorption by a semiconductor generates excess free carriers and results in an increase in conductivity47. In contrast, photogating effect originates from long-lived charge trap states26,48. In this phenomenon, only one kind of the photogenerated carrier (electrons or holes) contributes to photocurrent while other kind of carriers get trapped in the localized states and induce extra gate voltage49,50.

In general, photoconductive effect involves the relationship that the photocurrent is linearly dependent on the illumination power density ϕ, described by \({I}_{P}\propto {\varphi }^{\beta }\) (β = 1), while photogating effect shows a sub-linear dependency (β < 1) on power density21,22,23,24,25. Therefore, we have plotted photocurrent as a function of illumination power density for both devices depicted in Fig. 6(a). The parameter of β is determined as 0.34 for CZT and 0.168 for InCZT, revealing the photogating effect is the dominant photocurrent generation mechanism in both photodetectors devices. The photogating effect can be explained by the schematic shown in Fig. 7. The low value of β attributed to long-lived charge traps due to higher defects density present in both semiconductors mainly in InCZT6,12. The CZT crystal has relatively higher number of native defects due to Cd and Te vacancies. Szeles et al. have reported that the Cd vacancies are the dominant native shallow acceptor defect with a concentration of ∼1011 cm−3 in CZT51. On the other hand, in addition to Cd-native and Te vacancies, In-doping create a shallow donor level below the conduction band in InCZT crystal as shown in Fig. 1b . These defect play an important role in the electrical compensation and carrier trapping in CZT which is the primary reason for photogating effect52. Figure 7(a) shows the energy band alignment of photodetector devices under external bias in the dark. Presence of traps in the band gap of semiconductor act as the trapping and recombination center for the photogenerated charge carriers. Under the illumination, the photogenerated electron gets trapped in these localized states near the conduction band (CB) edge and only photogenerated hole contribute to the photocurrent as shown in Fig. 7(b)49,50,53,54. The trapped electron act as a local gate and collectively generate a local electric field and therefore reduce the resistivity of devices under illumination as shown in Fig. 6(b). On the other hand, the photogenerated hole can recirculate many times during the lifetime of the trapped electron, leading to a high EQE (>100%) as depicted in Fig. 4(b). The higher value of β for CZT is due to better crystalline quality and a small defect in CZT compare to InCZT crystals6,12. The In-doping introduce additional defects in the crystal lattice of CZT and hence InCZT crystal have higher density of trapped electrons, this leads to a higher EQE of InCZT based devices as compared to CZT.

Conclusions

In summary, we have successfully investigated photodetector performance of grown CZT and InCZT single crystals. The optoelectrical properties have been analyzed by measuring illuminance dependence I-V and I-t characteristics. The CZT photodetector exhibits a sensitive, fast and stable photoresponse to laser light of 633 nm. The In-doping in CZT crystal leads to deterioration of photoswitch ratio and specific detectivity while the improvement in responsivity and EQE of the device. Moreover, we have also investigated the photocurrent generation mechanism in both devices and found that the photogating effect is the dominant mechanism for both devices due to the presence of a large number of defects in the semiconductors. The preliminary results of our devices are superior to many other reported visible detectors, suggest that the CZT based crystal have desirable optoelectrical properties for future visible photodetector devices. The device performance can be further improved by reducing the defects, optimizing the growth parameters and using other dopant.

References

Carcelén, V., Hidalgo, P., Rodríguez-Fernández, J. & Dieguez, E. Growth of Bi doped cadmium zinc telluride single crystals by Bridgman oscillation method and its structural, optical, and electrical analyses. Journal of Applied Physics 107, 093501 (2010).

Yang, G. et al. Effects of In doping on the properties of CdZnTe single crystals. Journal of crystal growth 283, 431–437, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2005.06.035 (2005).

Franc, J. et al. CdTe and CdZnTe crystals for room temperature gamma-ray detectors. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 434, 146–151 (1999).

Foschini, L. Notes on the data analysis in high-energy astrophysics. arXiv preprint arXiv 0910, 2156 (2009).

Rybka, A. et al. Gamma-radiation dosimetry with semiconductor CdTe and CdZnTe detectors. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 531, 147–156 (2004).

Shkir, M. et al. Large Size Crystal Growth, Photoluminescence, Crystal Excellence, and Hardness Properties of In-Doped Cadmium Zinc Telluride. Crystal growth & design 18, 2046–2054, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.7b01483 (2018).

Del Sordo, S. et al. Progress in the development of CdTe and CdZnTe semiconductor radiation detectors for astrophysical and medical applications. Sensors 9, 3491–3526 (2009).

Owens, A. & Peacock, A. Compound semiconductor radiation detectors. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 531, 18–37 (2004).

Szeles, C., Soldner, S. A., Vydrin, S., Graves, J. & Bale, D. S. CdZnTe semiconductor detectors for spectroscopic x-ray imaging. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 55, 572–582 (2008).

Vadawale, S. et al. Hard X-ray continuum from lunar surface: results from high energy X-ray spectrometer (HEX) onboard Chandrayaan-1. Advances in Space Research 54, 2041–2049 (2014).

Schlesinger, T. et al. Cadmium zinc telluride and its use as a nuclear radiation detector material. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 32, 103–189 (2001).

Shkir, M. et al. VGF bulk growth, crystalline perfection and mechanical studies of CdZnTe single crystal: A detector grade materials. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 686, 438–446, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.05.308 (2016).

Asahi, T., Oda, O., Taniguchi, Y. & Koyama, A. Growth and characterization of 100 mm diameter CdZnTe single crystals by the vertical gradient freezing method. Journal of crystal growth 161, 20–27 (1996).

Rodríguez-Fernández, J. et al. Relationship between the cathodoluminescence emission and resistivity in In doped CdZnTe crystals. Journal of Applied Physics 106, 044901 (2009).

Yadong, X. et al. Study on temperature dependent resistivity of indium-doped cadmium zinc telluride. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 42, 035105 (2009).

Ackert, J. J. et al. High-speed detection at two micrometres with monolithic silicon photodiodes. Nature Photonics 9, 393–396 (2015).

Du, C. et al. Piezo‐Phototronic Effect Controlled Dual‐Channel Visible light Communication (PVLC) Using InGaN/GaN Multiquantum Well Nanopillars. Small 11, 6071–6077 (2015).

Huang, C.-C., Ho, C.-L. & Wu, M.-C. Highly uniform photo-sensitivity of large-area planar InGaAs pin photodiodes with low specific contact resistance of gallium zinc oxide. IEEE Electron Device Letters 36, 1066–1068 (2015).

Liu, X. et al. Low‐Voltage Photodetectors with High Responsivity Based on Solution‐Processed Micrometer‐Scale All‐Inorganic Perovskite Nanoplatelets. Small 13, 1700364 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. New UV‐A Photodetector Based on Individual Potassium Niobate Nanowires with High Performance. Advanced Optical Materials 2, 771–778 (2014).

Kind, H., Yan, H., Messer, B., Law, M. & Yang, P. Nanowire ultraviolet photodetectors and optical switches. Advanced Materials 14, 158–160 (2002).

Zhai, T. et al. Recent Developments in One‐Dimensional Inorganic Nanostructures for Photodetectors. Advanced Functional Materials 20, 4233–4248 (2010).

Tao, Y., Wu, X., Wang, W. & Wang, J. Flexible photodetector from ultraviolet to near infrared based on a SnS2 nanosheet microsphere film. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 3, 1347–1353 (2015).

Soci, C. et al. ZnO nanowire UV photodetectors with high internal gain. Nano letters 7, 1003–1009 (2007).

Tan, M. et al. 2D Lead Dihalides for High‐Performance Ultraviolet Photodetectors and their Detection Mechanism Investigation. Small 13, 1702024 (2017).

Li, L. et al. Ternary Ta2NiSe5 Flakes for a High‐Performance Infrared Photodetector. Advanced Functional Materials 26, 8281–8289 (2016).

Huo, N. et al. Photoresponsive and gas sensing field-effect transistors based on multilayer WS 2 nanoflakes. Scientific Reports 4, srep05209 (2014).

Zhang, W. et al. High‐gain phototransistors based on a CVD MoS2 monolayer. Advanced Materials 25, 3456–3461 (2013).

Michaelson, H. B. The work function of the elements and its periodicity. Journal of Applied Physics 48, 4729–4733 (1977).

Ashraf, I., Salem, A. & Al-Juman, M. A. Structure and transport properties of Tl2Te3 single crystals. Results in Physics 10, 281–286 (2018).

Shkir, M., Ashraf, I. M. & AlFaify, S. Surface area, optical and electrical studies on PbS nanosheets for visible light photo-detector application. Physica Scripta 94, 025801 (2019).

Takahashi, T. & Watanabe, S. Recent progress in CdTe and CdZnTe detectors. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 48, 950–959 (2001).

Szeles, C., Cameron, S. E., Ndap, J.-O. & Chalmers, W. C. Advances in the crystal growth of semi-insulating CdZnTe for radiation detector applications. Nuclear Science, IEEE Transactions on 49, 2535–2540 (2002).

Zheng, W. et al. High‐Crystalline 2D Layered PbI2 with Ultrasmooth Surface: Liquid‐Phase Synthesis and Application of High‐Speed Photon Detection. Advanced Electronic Materials 2, 1600291 (2016).

Wang, Y., Gan, L., Chen, J., Yang, R. & Zhai, T. Achieving highly uniform two-dimensional PbI2 flakes for photodetectors via space confined physical vapor deposition. Science Bulletin 62, 1654–1662 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Ultrathin SnSe2 Flakes Grown by Chemical Vapor Deposition for High‐Performance Photodetectors. Advanced Materials 27, 8035–8041 (2015).

Ma, Y. Ultrathin SnSe2 flakes: a new member in two-dimensional materials for high-performance photodetector. Sci. Bull 60, 1789–1790 (2015).

Yin, Z. et al. Single-layer MoS2 phototransistors. ACS Nano 6, 74–80 (2011).

Perea‐López, N. et al. Photosensor device based on few‐layered WS2 films. Advanced Functional Materials 23, 5511–5517 (2013).

Mohd Taukeer, K. et al. High performance visible light photodetector based on TlInSSe single crystal for optoelectronic devices. Physica Scripta 94, 105816 (2019).

Wei, Q. et al. Large-sized PbI2 single crystal grown by co-solvent method for visible-light photo-detector application. Materials Letters 193, 101–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2017.01.049 (2017).

Greenham, N. C., Peng, X. & Alivisatos, A. P. Charge separation and transport in conjugated-polymer/semiconductor-nanocrystal composites studied by photoluminescence quenching and photoconductivity. Physical Review B 54, 17628 (1996).

Peumans, P., Bulović, V. & Forrest, S. Efficient, high-bandwidth organic multilayer photodetectors. Applied Physics Letters 76, 3855–3857 (2000).

Rauch, T. et al. Near-infrared imaging with quantum-dot-sensitized organic photodiodes. Nature Photonics 3, 332 (2009).

Lan, C. et al. Large‐Scale Synthesis of Freestanding Layer‐Structured PbI2 and MAPbI3 Nanosheets for High‐Performance Photodetection. Advanced Materials 29, 1702759 (2017).

Sun, H. et al. Self‐Powered, Flexible, and Solution‐Processable Perovskite Photodetector Based on Low‐Cost Carbon Cloth. Small 13, 1701042 (2017).

Xie, C., Mak, C., Tao, X. & Yan, F. Photodetectors Based on Two‐Dimensional Layered Materials Beyond Graphene. Advanced Functional Materials 27, 1603886 (2017).

Furchi, M. M., Polyushkin, D. K., Pospischil, A. & Mueller, T. Mechanisms of photoconductivity in atomically thin MoS2. Nano letters 14, 6165–6170 (2014).

Konstantatos, G. & Sargent, E. H. Nanostructured materials for photon detection. Nature nanotechnology 5, 391–400 (2010).

Sun, Z. et al. Infrared photodetectors based on CVD‐grown graphene and PbS quantum dots with ultrahigh responsivity. Advanced Materials 24, 5878–5883 (2012).

Szeles, C. Advances in the crystal growth and device fabrication technology of CdZnTe room temperature radiation detectors. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 51, 1242–1249 (2004).

Awadalla, S. A. et al. Isoelectronic oxygen-related defect in CdTe crystals investigated using thermoelectric effect spectroscopy. Physical Review B 69, 075210 (2004).

Luo, F. et al. High responsivity graphene photodetectors from visible to near-infrared by photogating effect. AIP Advances 8, 115106 (2018).

Fang, H. & Hu, W. Photogating in low dimensional photodetectors. Advanced Science 4, 1700323 (2017).

Zhong, M. et al. Flexible photodetectors based on phase dependent PbI 2 single crystals. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 4, 6492–6499 (2016).

Chitara, B., Panchakarla, L., Krupanidhi, S. & Rao, C. Infrared photodetectors based on reduced graphene oxide and graphene nanoribbons. Advanced Materials 23, 5419–5424 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Broadband high photoresponse from pure monolayer graphene photodetector. Nature Communications 4, 1811 (2013).

Wu, J.-J., Tao, Y.-R., Wu, Y. & Wu, X.-C. Ultrathin SnS2 nanosheets of ultrasonic synthesis and their photoresponses from ultraviolet to near-infrared. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 231, 211–217 (2016).

Tsai, D.-S. et al. Few-layer MoS2 with high broadband photogain and fast optical switching for use in harsh environments. ACS Nano 7, 3905–3911 (2013).

Yao, J., Zheng, Z., Shao, J. & Yang, G. Stable, highly-responsive and broadband photodetection based on large-area multilayered WS 2 films grown by pulsed-laser deposition. Nanoscale 7, 14974–14981 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Authors from KKU express their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through research groups program under grant number R.G.P. 2/42/40.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author 1 (Mohd. Shkir): Have synthesized/grown the final product and written the manuscript. Author 2 (Mohd Taukeer Khan): He has contributed in results and discussion part. Author 3 (I.M. Ashraf): Has helped in performing the electrical measurements. Author 4 (Abdullah Almohammedi): He contributed in analysis part. Author 5 (E. Dieguez): has contributed in scientific discussion. Author 6 (S. AlFaify): Has contributed in performing the characterization and analyzing of the final product.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shkir, M., Khan, M.T., Ashraf, I.M. et al. High-performance visible light photodetectors based on inorganic CZT and InCZT single crystals. Sci Rep 9, 12436 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48621-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48621-3

This article is cited by

-

Investigating ions concentration effect on structural and optical characteristics of metal-sulphide’s thinfilms for photonic devices

Journal of Optics (2024)

-

Highly efficient ultraviolet photodetector based on molybdenum-doped nanostructured NiO/ITO thin film

Applied Physics A (2023)

-

Synthesize and characterization of Co-complex as interlayer for Schottky type photodiode

Polymer Bulletin (2022)

-

Influence of In Doping on Physical Properties of Co-precipitation Synthesized CdO NPs and Fabrication of p-Si/n-CdIn2O4 Junction Diodes for Enhanced Photodetection Applications

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

-

Photoactive Copper-Doped Zinc Stannate Thin Films for Ultraviolet–Visible Light Photodetector

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.