Abstract

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus develop in the same aquatic sites where they encounter microorganisms that influence their life history and capacity to transmit human arboviruses. Some bacteria such as Wolbachia are currently being considered for the control of Dengue, Chikungunya and Zika. Yet little is known about the dynamics and diversity of Aedes-associated bacteria, including larval habitat features that shape their tempo-spatial distribution. We applied large-scale 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to 960 adults and larvae of both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes from 59 sampling sites widely distributed across nine provinces of Panama. We find both species share a limited, yet highly variable core microbiota, reflecting high stochasticity within their oviposition habitats. Despite sharing a large proportion of microbiota, Ae. aegypti harbours higher bacterial diversity than Ae. albopictus, primarily due to rarer bacterial groups at the larval stage. We find significant differences between the bacterial communities of larvae and adult mosquitoes, and among samples from metal and ceramic containers. However, we find little support for geography, water temperature and pH as predictors of bacterial associates. We report a low incidence of natural Wolbachia infection for both Aedes and its geographical distribution. This baseline information provides a foundation for studies on the functions and interactions of Aedes-associated bacteria with consequences for bio-control within Panama.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The arboviral disease vectors of Dengue (DENV) and chikungunya (CHIKV) viruses, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus are invasive mosquitoes that utilise the same habitats and hosts as they expand and naturalise. This includes the use of water-filled containers around human settlements for immature development, where larvae compete for space and resources, feeding on microorganisms or detritus in the water. However, little descriptive information exists to date about whether Aedes species exhibit niche partitioning in the microorganisms they encounter and utilise. Furthermore, since mosquitoes acquire a large proportion of their bacterial microbiota as larvae, resource use in aquatic habitats are likely to impact the core microbiota of adult mosquitoes1,2. This is important since the capability of a female mosquito to transmit pathogens to humans (e.g., vectorial capacity) is directly influenced by the microbiota, through the production of metabolites3, resource competition4, regulation of miRNA’s5,6 and alteration of the insect immune response7. Yet, very little is known currently as to how the larval microbial community influences the microbiota of adult mosquitoes. Resident microbiota can also alter mosquito life history traits important for ecological success and disease transmission, impacting on host fitness through nutrient acquisition8, reproduction9, development1,10,11 and predator and pathogen defence12,13. Hence, microbial communities could influence the outcome of inter-specific competition at the larval stage and the vectorial capacity of adult Aedes mosquitoes, ultimately leading to changes in human risk of exposure to arboviral diseases such as Dengue, Chikungunya and Zika. Decoding features of the larval habitat that shape Aedes-bacterial interactions and understanding the tempo-spatial dynamics of Aedes microbes, including within and between-species differences, provides the foundation on which to unravel their epidemiological impact.

Because mosquito-associated bacteria could alter disease transmission, there is interest in using intrinsic bacteria to modify vector populations. This provides an alternative to chemical spray, which is compromised by the widespread development of insecticide resistance. The intracellular bacterium Wolbachia has been proposed as a strategy to diminish disease transmission through the infection of Aedes mosquitoes. Wolbachia can inhibit the replication of Yellow Fever (YFV), Dengue, Chikungunya and Zika viruses both in vitro14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 and in vivo23. Moreover, Wolbachia has been proposed as a means to control mosquito populations through the sterility induced by cytoplasmic incompatibility. The strain of Wolbachia currently proposed for mosquito control, wMelPop, successfully spreads through the population because of a fitness advantage conferred by the infected female. This occurs because males infected with the wMelPop strain cannot produce viable eggs on reproduction with un-infected females while infected females are able to produce eggs that hatch with both infected and uninfected males24. The effective spread of introduced Wolbachia among natural populations relies on a gene drive system that can be impacted by the interaction of different Wolbachia strains and bacterial community members, producing variable fitness consequences25,26. Therefore, establishing the natural occurrence and geographic distribution of Wolbachia is central to the design and implementation of vector/disease mitigation strategies. Although commonly found in wild Ae. albopictus27, natural infection with Wolbachia in Ae. aegypti has only been recently described1, which could be perhaps due to a lack of studies specifically targeting Wolbachia in wild populations of Ae. aegypti at a global scale.

Herein, we conduct extensive collections of Aedes mosquitoes across the entire country of Panama and use 16S rRNA metabarcoding to characterise their microbiota. To date, efforts to characterise the bacterial community of wild mosquitoes have been limited to over a small geographic scale1,2,25,28,29,30,31,32,33. This includes very little related work on the arboviral disease vectors Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, despite their considerable impact on public health34,35,36. In Panama, the two species have different population histories; Ae. aegypti has been present since the 17th Century34,37, whereas Ae. albopictus was recently introduced into Panama in 2002. There is also evidence for repeated introductions into Panama of both species from the Americas and Europe38. Preliminary data on mosquito occurrence across Panama supports an on-going pattern of competitive displacement, whereby the invasive spread of Ae. albopictus has modified the species distribution of Ae. aegypti; species are rarely found in the same oviposition site throughout their geographic range while Ae. aegypti are more associated with populated areas.

Since the geographical distribution of Aedes species (e.g., co-existence) has not been fully characterised across Panama, our intention is not to test whether bacteria are shared across the same oviposition sites, but rather we use country-wide data i) to describe the intra- and inter-species microbial communities associated with larval and adult stages of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, and ii) to determine whether features of larval habitats including geographic location, type of container material and physical variables of the water (pH and temperature) influence the microbiota of these mosquitoes. Furthermore, given the interest in using Wolbachia as a biocontrol strategy to diminish arboviral disease in Panama, we use conventional PCR and Sanger sequencing on 16S Wolbachia positive samples to describe Wolbachia strain composition and geographic distribution across the country. Therefore, in addition to its ecological and epidemiological consequences, characterisation of the bacterial community of Aedes mosquitoes would provide valuable baseline information for trials of vector population control with genetically-engineered bacteria.

Results

Composition and structure of Aedes-associated bacterial communities

Preliminary sequencing of seven pools of six mosquitoes each captured a comparable level of bacterial diversity to individual component mosquitoes (Mann Whitney U of Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity values, W = 58, P > 0.05), therefore informing our decision to process a larger number of individuals by pooling mosquitoes of the same species from the same oviposition site. In total, 4,921,352 sequence reads of bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicons were generated from DNA pools and individually processed mosquitoes representing 960 samples of immature and adult Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus. This included 75 pools of Ae. albopictus representing 30 sampling sites, 79 pools of Ae. aegypti representing 30 sampling sites, 20 individual adult Ae. albopictus from seven sites and 16 individuals of adult Ae. aegypti from six sites. In total, we sampled 59 widely distributed natural habitats across Panama (Fig. 1, Table S1) and recorded co-existence of both Aedes at eight of the same oviposition sites in Panama, Los Santos and Chiriquí on the border with Costa Rica (~5%). The mean number of reads per pool or individual sample was 27,341 ± SE 3,310. Rarefaction curves were close to saturation at a sampling depth of 1,000, indicating that the bacterial diversity present in Aedes mosquitoes was captured (Figs 2, S1). After quality filtering, 3,568,301 sequences were retained from 681 samples, including 58 pools (26% larvae) and 10 individual adult Ae. aegypti and 51 pools (29% larvae) and 17 individual adult Ae. albopictus. These samples comprised 721 unique operational taxonomic units (OTUs), averaged at 48 to 52 OTU’s per individual or mosquito pool.

Sampling locations of Aedes mosquitoes across provinces and indigenous territories (also known as “Comarcas”) of Panama, including those confirmed to be infected with Wolbachia: Bocas del Toro (BOC), Chiriquí (CHI), Veraguas (VER), Herrera (HER), Los Santos (LOS), Coclé (COC), Colón (COL), Panamá Oeste (PAO), Panamá (PAN), Darién (DAR), Ngöbe Buglé (NGO), Kuna Yala (KUN), and Emberá (EMB).

Alpha diversity of the bacterial communities found in larvae and adults of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus collected from human inhabited environments across Panama as distinguished by the province from which they were collected. Mean Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (±SE) of each sample group is shown across different sequencing depths.

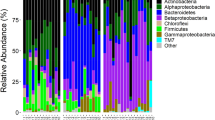

In total, the bacterial communities analysed composed 12 phyla, 24 classes, 51 orders, 76 families and 115 genera (Table S2). Only 16 genera had a relative abundance over 1%, suggesting that few bacterial groups are able to colonise the mosquito (Table S2). We found that members of Proteobacteria dominated the communities, composing upwards of 88% of the identified OTU’s for each of the two mosquito species, while Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were also represented although at lower relative abundances. All other Phyla had an overall relative abundance of less than 2% (Fig. 3, Table S3).

Aedes intra- and inter-species bacterial diversity

We found a high degree of intraspecific variation in the bacterial community of both Aedes species, demonstrated by high average Bray-Curtis distances of 0.80 and 0.84 for Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, respectively. In support of this, certain bacteria members were prevalent in one pool of individuals but rare or entirely absent from another, with the highest variation between members of Flavobacteriales, Rhodocyclales, Rhodospirillales and Aeromonadales (Fig. 4). For instance, Flavobacteriales (Bacteroidetes) and Rhodospirillales (Proteobacteria) although frequently found in smaller proportions, dominated three pools of adult Ae. aegypti from the Azuero Peninsula, and two pools of adult Ae. albopictus from Chiriquí, respectively, contributing between 52 and 90% of the bacterial OTU’s in these places. Furthermore, we observed a higher bacterial diversity in larvae with a significantly different microbial community than newly emerged adults in both Ae. aegypti (PERMANOVA of unweighted UNIFRAC distances, pseudo-F = 5.16, P < 0.01) and Ae. albopictus (PERMANOVA of unweighted UNIFRAC distances, pseudo-F = 3.35, P < 0.05) (Tables 1, S1, Fig. S1).

Bar plot to show the proportion of different bacterial classes within each mosquito or pool of mosquitoes tested from. (a) Western Panama including Bocas del Toro, Chiriquí, Herrera and Veraguas. (b) Los Santos and (c). Eastern Panama including Colón, Coclé, Darién and the province of Panama. Bacterial classes with an overall relative abundance of at least 1% within either species are specified. * Indicate an inter-species comparison of equivalent sampling sites.

A large proportion of bacterial OTU’s (67.7%) were shared between samples of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus overall, although a lesser extent was shared between species on comparison of either only adults or larvae (59.4% and 47.8% of OTU’s, respectively) (Fig. 5). Of the 8 of 59 oviposition sites where both species co-occurred, three out of eight (~38%) oviposition sites retained in the analysis after quality filtering, provided a one to one species comparison of adult mosquitoes and revealed the same trend of shared bacterial community members, yet high intraspecific variability (Fig. 4). Despite species sharing a considerable proportion of bacteria, we found several rare taxa unique to Ae. aegypti, reflected in a higher bacterial diversity within both adults (Mann-Whitney U of Faith’s PD, W = 1917, P < 0.01) and larvae (Mann-Whitney U of Faith’s PD, W = 216, P < 0.01) of this species when compared to Ae. albopictus (Tables 1, S4, Fig. S1). This trend holds within the three sites of co-existence, with a higher Faith’s phylogenetic distance for Ae. aegypti (4.05 ± 1.28) compared to Ae. albopictus (3.56 ± 1.51). Furthermore, random forest analysis can successfully assign adult Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus to the correct species class with a high accuracy of 0.82 for both although estimates for larvae were less exact, with predicted accuracies of 0.67 and 1.00, respectively. The fact that this accuracy is particularly lower for Ae. aegypti than for Ae. albopictus supports a higher degree of bacterial variability at the immature stage than as emergent adults with Bray-Curtis distances of 0.79 and 0.76, for this species respectively. Indicator species analysis did not identify any OTU’s characteristic of Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus after Benjamini & Hochberg correction for multiple tests (Tables S5 and S6).

Larval habitat features and bacterial composition

We observed few pertinent differences between both the bacterial community of larvae and adult Aedes species due to larval habitats features including geographic distribution, type of container material and associated environmental variables of the water. Principle Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) revealed no clear differences between the bacterial communities for the majority of compared categories, with only few statistically significant comparisons based on PERMANOVA between oviposition sites having different container materials and geographic distribution (Tables S7, S8, Fig. 6). For instance, PCoA revealed that mosquito species developing in containers with metal and ceramic tend to harbour a distinct community of microbes. Indeed, a greater proportion of Bacteroidia and Saprospirae were isolated from Ae. aegypti developing in metal containers while a greater proportion of Alphaproteobacteria, namely Rhizobiales, Sphingomonadales, Rhodocyclales and Rhodobacterales, were isolated from Ae. albopictus developing in ceramic (Fig. 6).

Water temperature and pH of the larval habitat had no significant effect on the microbiota acquired by the mosquito host (Fig. S3).

Wolbachia occurrence and distribution

We found Wolbachia 16S rRNA positive samples in both Aedes species. This included 11 pools and five individuals of Ae. albopictus (~15% samples), of both adults and larvae originating from plastic and ceramic containers and used-tyres widespread across Panama. Wolbachia 16S rRNA was also amplified and sequenced from one adult of Ae. aegypti originating from a plastic container in Veracruz, Panama (Fig. 1). Amplification of the wsp gene in 11 samples of Ae. albopictus from the provinces of Panama, Los Santos and Chiriquí revealed that all tested individuals were infected with the same strain of Wolbachia (wAlB) within supergroup B, known to occur naturally and widely in Ae. albopictus (Strain id 1847 included within the https://pubmlst.org database). The wsp gene could not be amplified from Ae. aegypti, for which Wolbachia was detected at a very low relative abundance (0.003%) compared to Ae. albopictus (0.4% overall or between 0.01–0.8% per wsp positive sample).

Discussion

Dynamics and diversity of Aedes-associated bacteria

Here, we provide the first descriptive study of the bacterial community within the arboviral disease vectors, Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus in Panama. We reveal that the core microbiota of both Aedes species is underpinned by extensive intraspecific variation including notable differences between conspecific mosquitoes collected from the same geographical location and comparable oviposition sites. This outcome suggests that individuals of both species acquire the basis of their microbiota during larval development although many OTU’s are either rare or variable in space and time, thus reflecting a high degree of stochasticity in their natural environment. The core microbiota of Aedes species was dominated by few bacterial phyla, which is similar to that previously described for Anopheles, Culex and Aedes mosquitoes25,29,31,39,40,41,42,43. Furthermore, in agreement with previous studies, we found that bacterial classes associated with Aedes mosquitoes included gram-negative Gammaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Bacteroidia and Flavobacteria and gram-positive Actinobacteria, suggesting that these microbes have either evolved a close relationship or are the more prolific bacterial types within the mosquito host25,44.

We found differences between the bacterial composition of larvae and adults in both Aedes species, with a higher taxonomic diversity present in the former life stage. This is expected given that along with permanent bacteria, transient bacteria acquired for nutrition will also be detected in larvae, if they remain undigested in the gut, and because adult mosquitoes lose bacterial diversity as they shed their skin on pupal emergence45. Since we pooled whole larvae, we cannot determine whether the OTU’s differentially abundant between the life stages are gut microbes. However, findings indicate that Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus share a fairly similar niche in terms of the bacterial community they host at the larval and adult stages, except for the presence of some rare and unique bacterial community members in Ae. aegypti. That Ae. aegypti has a higher bacterial diversity than Ae. albopictus at the larvae and adult stages suggests it could be more a generalist aquatic feeder or has a higher tolerance of bacterial commensalism for which its members may have evolved specific functions44. However, that these mosquitoes tend to share a large proportion of bacterial types signals the need for further work to understand whether resource competition in association with bacterial acquisition can impact on mosquito development and survival.

Variation in the microbiota of mosquitoes at the intra- and interspecific levels has been previously linked to environmental variation in container breeding sites, with three mosquito species showing a more similar microbial profile at nearby versus more distant sites in the south-eastern United States and local clustering of meta-bacterial profiles of Anopheles in Burkina Faso1,28. However, in the case of invasive and ecologically similar Aedes species, the outcomes of high intraspecific and low interspecific bacterial variation cannot be easily explained by differences in larval habitat features, including geographic distribution, type of container material and associated environmental variables of the water. We observed few meaningful differences between categories of larval habitat features, with the only significant differences observed between bacterial communities of Ae. aegypti from metal containers and Ae. albopictus from ceramic containers. Moreover, we found no support for geography and water environmental variables as meaningful predictors of Aedes bacterial associates. However, it is likely that many small effects from biotic and abiotic factors act in combination to explain the core microbiota of Aedes mosquitoes, including a variety of unexplored factors such as bacterial competition in the host, interspecific competition in the aquatic environment, variation in the water and surrounding environment and genetic background46,47,48.

The role of bacteria in shaping Aedes phenotype

The high variation in the microbial community among mosquito pools of the same species could translate to high variation in vector competence within Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus. Studies relating variation in the microbial community to the arboviral competence of Aedes mosquitoes has the potential to reveal bacterial members important in either mitigating or facilitating disease dissemination. Information on the intraspecific variability of vector competence of either Aedes is currently lacking within Panama. Yet, if the microbial community is a strong determinant of disease transmission ability and based on the high intrapopulation variability that we have observed, it is expected that vector competence would likewise be highly variable within a single population. Previous studies have demonstrated high intraspecific variation in vector competency in Brazilian populations of Ae. aegypti49,50,51, which could be mediated by intrinsic bacteria. For example, members of the genus Serratia, which we found to be 1% prevalent in Ae. aegypti, have been shown to increase DENV-2 susceptibility in the females of this species52.

The microbiota identified in both mosquito species should be the target of further experimental work in order to investigate their functions and role in mosquito fitness. Bacterial residents can contribute to the hosts fitness by influencing their development1,10,11,53, reproduction54 and nutrition55,56 with those present in a wide-range of taxa potentially involved in their basic functions57. Little is currently known about the functional roles and interactions of bacteria within mosquito hosts, but several microbes identified in this study have been previously implicated in blood and nectar assimilation (e.g. Corynebacterium, Serratia), known to fix nitrogen (e.g. Xanthobacter, Novispirillum), act as an attractant to gravid females (e.g. Enterobacter, Acinetobacter) or have the ability to impact on reproduction (e.g. Stenotrophomonas)44,46,54,58,59,60 (Table S2). Additionally, it has been found that the presence of a particular bacteria (eg. Wolbachia, Chromobacteria, Proteus, Paenibacillus) can inhibit or promote infection with viruses61,62,63. Exploration of the relationship between mosquito bacterial communities and intraspecific disease competence would be of value along with work targeting the ecological factors that underpin the relevant variability in their microbiota.

Implications for Wolbachia bio-control in Panama

The presence of Wolbachia in Aedes mosquitoes has important ramifications for attempts at biocontrol that introduce either naturally occurring or modified Wolbachia strains to reduce the transmission of Dengue17,20,64, Chikungunya14,17,18 and Zika viruses65. So as to drive Wolbachia spread through a natural mosquito population on the basis of cytoplasmic incompatibility, there must be sufficient infected males present to confer a fitness advantage to the infected female66. The wALBb strain we have observed has the potential to facilitate arboviral control and may indeed prove a more acceptable disease control strategy than other genetically modified Wolbachia strains, given its natural occurrence within Panama. Infection with wALBb is known to reduce DENV replication within Ae. aegypti67, although further investigation is needed to understand its impact on viral replication within Ae. albopictus, including its implications for other arboviruses and population specific effects to be considered for biocontrol. We have observed widespread natural infection of Wolbachia wALBb within Ae. albopictus across Panama, although this is not as common as in previous studies, which report infection rates of over 90% in populations sampled from USA29, Malaysia27, Thailand68 and La Reunion69. Disease control using wALBb induced cytoplasmic incompatibility would therefore require the release of a large number of laboratory infected mosquitoes in order to push the infection rate over the required threshold. The presence of naturally occurring Wolbachia has the potential to interfere with cytoplasmic compatibility induced by introduced Wolbachia strains, or alternatively alter fitness effects and so the dynamics of the proposed gene drive system26. However, if the release of the proposed strain for population control, wMelPop, is considered within Panama, the presence of wALBb is unlikely to hinder control efforts, given that it is able to stably co-infect the mosquito host with minimal fitness costs70.

Until recently, it was widely accepted that Ae. aegypti does not habour natural infections of Wolbachia, although infection has since been reported in mosquitoes from Jacksonville and Houston, USA1,32. We found one individual of Ae. aegypti infected with Wolbachia in Veracruz, Panama, suggesting that although uncommon, it does occur and further screening would possibly yield further positives. A full scale assessment is required within Panama, with future work focused on understanding of the prevalence of natural Wolbachia infections acquired during the adult life stage and any potential barriers to mosquito dispersal, since these can impact on the success of Wolbachia spread66,71.

Limitations of the study

There are potentially finer scale interspecific differences between Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus that are difficult to assess without controlling for the high degree of intraspecific bacterial variability we have observed within these mosquitoes. A better understanding of determinant factors including temporal changes in relation to the bacterial composition of habitat water is required to account for variability in individuals from the same oviposition site. Furthermore, there may be inter-specific differences acquired during the adult life stage, which were not the focus of this study44. Since there was limited information on Aedes distributions across Panama, we sampled mosquitoes systematically across the entire country in order to decipher both the competition landscape and bacterial associations under different habitat conditions. We found few sites of co-existence, highlighting biological competition as a potentially important determinant of species distributions. However, this could have limited our ability to decipher inter-species differences. Future studies may focus on areas of Aedes co-existence at the landscape and microhabitat levels, including within the Azuero Peninsula, Panama City or Colon. The resolution of the data depends on variability at the 16S rRNA region, primer affinity, and composition of the bacterial database72. Therefore, the exploration of Aedes bacterial communities with multiple genomic markers and culture dependent approaches with different media has the potential to increase the number or relative abundance of discoverable genera.

Conclusion

Resident bacteria are likely to impact on mosquito host fitness, influence the outcome of biological competition and impact on vector competence, yet research efforts to gain insight into the dynamics and diversity of Aedes associated bacteria have been limited so far. Our study provides the basis for understanding the bacterial associations of Aedes mosquitoes across Panama, while highlighting the many avenues that remain to be explored. An understanding of the biological and ecological factors influencing bacterial associations will be paramount to resolve the consequences of the microbiota for mosquito-borne disease.

Materials and Methods

Mosquito collection and sample preparation

All Aedes mosquitoes were collected as larvae through the active surveillance of natural breeding sites around settlements across 37 locations and 59 oviposition sites in Panama (Fig. 1, Table S1). At the time of collection, the water temperature and pH were taken three times and averaged to account for variability in the readings. Additional details about our sampling protocol can be obtained from Eskildsen et al.38. Mosquitoes from each collection site were brought to the laboratory and reared to adulthood under standardized conditions (e.g., LD 12:12 hours, 85% relative humidity, and 30 °C, which are similar to those encountered throughout natural sites in Panama) in separate plastic glasses and the habitat water. On reaching fourth instar, larvae were placed on blotting paper and rinsed three times with distilled water to remove any surface bacteria. Larvae were stored dry in separate Eppendorf tubes or in 70% ethanol. Each emergent adult was placed at -20 °C for 20 minutes to induce death before transfer to a sterilised Eppendorf tube. Both larvae and adults were identified to species level using the morphological key of Rueda et al.73 and stored at −20 °C until DNA was extracted.

DNA extraction, 16S rRNA gene library and sequencing

To assess whether pooling mosquitoes could capture the same level of bacterial diversity as processing individual mosquitoes, preliminary sequence data was captured for 7 pools of six Ae. aegypti and the component individual mosquitoes of those pools using the methods and computational processing described below. To analyse the whole-body microbial community of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, the DNA of 960 mosquitoes (470 Ae. albopictus and 490 Ae. aegypti) were extracted individually using a Biosprint® 96 DNA Blood kit (Qiagen). DNA pools were made by combining 2 µl of DNA extract from each of six individual mosquitoes from the same oviposition site (creating 75 sample pools of Ae. albopictus and 79 pools of Ae. aegypti). In addition, 20 Ae. albopictus and 16 Ae. aegypti, originating from oviposition sites with few mosquitoes, were processed individually. Pooled or individual DNA was then used to amplify the V4 region of the 16S rRNA74 locus in triplicate 12.5 μl reactions using a two-step PCR protocol. PCR 1 included 5 µl of 2X Maxima HotStart PCR Master Mix (Thermo), 0.2 µl of each primer (which included an Illumina sequencing primer on the 5′ end (10 mM)), and 1 µl of DNA. Cycling conditions had an initial denaturation step of 3 min at 94 °C proceeding 25 cycles of 94 °C for 45 sec, 50 °C for 60 sec, and 72 °C for 90 sec, followed by 10 min at 72 °C extension. The resulting triplicate PCR products were pooled and 1 µl used as template for a second PCR of six cycles to add on unique barcodes and Illumina sequencing adaptors. Resulting reactions were cleaned and normalized using PCR Normalization plates (Charm Biotech), pooled into a single species library and concentrated using Kapa magnetic beads. DNA concentration was verified with the Qubit HS assay (Invitrogen) and the quality checked with a Bioanalyzer dsDNA High Sensitivity assay. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq on a 2 × 250 paired end run.

Data Analysis of 16S Metadata

The majority of analysis of sequences reads was performed using the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) software package versions 1.9.1 and 2.075 using the forward reads of the V4 hypervariable region. The reverse reads were not used due to their reduced data quality, but results based on their analysis are provided for comparison as supplementary information. Quality control was performed with the Dada2 pipeline with forward sequences trimmed to 230 base pairs after the visual inspection of base quality score plots. The identities of OTU’s were designated using a Naive Bayes classifier trained on the Greengenes 99% sequence similarity database v13.8, where sequences were trimmed to 251 base pairs of the sequenced 16S regions bound by the 515F and 806R primer pair. Low abundance OTU’s (0.005%) were filtered from the resulting OTU table, recommended to remove potential sequencing errors76.

Informed by rarefaction curves, the feature table was standardised to a sequencing depth of 1000 before alpha and beta diversity values were calculated using the diversity core-metrics function in Qiime275. Significance between the alpha diversity of metadata groups was determined using a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for two group comparisons in the R package Stats77. Significance differences between the beta diversity of metadata groups were calculated with PERMANOVA on both Bray-Curtis and unweighted UNIFRAC distance matrixes, as a widely applied and distribution-free test. To visualise dissimilarity between beta-diversity distance matrixes, Principle Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) plots were generated using unweighted UNIFRAC distances in the R program Phyloseq78. Heat maps were generated in Qiime 1 to visualise the profile of the microbial community with increasing values of water pH and temperature. To determine whether Aedes species could be accurately classified according to their microbial profile, a Random Forests regression model was run using the supervised learning classifier in Qiime2 with our microbial OTU data as a training dataset. Analysis was performed in the R package indicspecies79 to identify the bacterial OTU’s significantly indicative of the different Aedes species.

Wolbachia PCR

Individual mosquitoes within pools positive for 16S Wolbachia were tested for the presence of the Wolbachia surface protein gene (wsp) in a PCR reaction using Maxima Hot Start Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) under the guidelines and PCR cycling conditions provided in Baldo et al.80. Positive PCR products were cut from an agarose gel, digested with GELase and purified with Serapure beads before sequencing on an ABI 3500XL Sanger Sequencer using BigDye Terminator chemistry. Resulting Wolbachia wsp sequences were edited and aligned in Geneious v11.0.5, assigned allele numbers and identified to strain using the Wolbachia wsp database (https://pubmlst.org/wolbachia). Data is available in GenBank (Accession numbers MH392327-MH392336).

Data Availability

The 16S amplicon sequence datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Genbank repository (BioProject PRJNA523634). Wolbachia wsp sequences are also available (Accession numbers MH392327-MH392336).

References

Coon, K. L., Brown, M. R. & Strand, M. R. Mosquitoes host communities of bacteria that are essential for development but vary greatly between local habitats. Mol. Ecol. 25, 5806–5826, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13877 (2016).

Duguma, D. et al. Bacterial communities associated with Culex mosquito larvae and two emergent aquatic plants of bioremediation importance. PLoS One 8, e72522, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072522 (2013).

Ramirez, J. L. et al. Chromobacterium Csp_P reduces malaria and dengue infection in vector mosquitoes and has entomopathogenic and in vitroanti-pathogen activities. PLOS Pathog. 10, e1004398, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004398 (2014).

Caragata, E. P., Rancès, E., O’Neill, S. L. & McGraw, E. A. Competition for amino acids between Wolbachia and the mosquito host, Aedes aegypti. Microb. Ecol. 67, 205–218, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-013-0339-4 (2014).

Hussain, M., Frentiu, F. D., Moreira, L. A., O’Neill, S. L. & Asgari, S. Wolbachia uses host microRNAs to manipulate host gene expression and facilitate colonization of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 9250–9255, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1105469108 (2011).

Mayoral, J. G., Etebari, K., Hussain, M., Khromykh, A. A. & Asgari, S. Wolbachia infection modifies the profile, shuttling and structure of MicroRNAs in a mosquito cell line. PLoS One 9, e96107, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096107 (2014).

Xi, Z., Ramirez, J. L. & Dimopoulos, G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLOS Pathog. 4, e1000098, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000098 (2008).

De Gaio, A. O. et al. Contribution of midgut bacteria to blood digestion and egg production in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) (L.). Parasit. Vectors 4, 105, https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-4-10 (2011).

Gendrin, M. et al. Antibiotics in ingested human blood affect the mosquito microbiota and capacity to transmit malaria. Nat. Commun. 6, 5921, https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-4-105 (2015).

Coon, K. L., Vogel, K. J., Brown, M. R. & Strand, M. R. Mosquitoes rely on their gut microbiota for development. Mol. Ecol. 23, 2727–2739, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12771 (2014).

Coon, K. L. et al. Bacteria-mediated hypoxia functions as a signal for mosquito development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, E5362–E5369, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702983114 (2017).

Dong, Y., Manfredini, F. & Dimopoulos, G. Implication of the mosquito midgut microbiota in the defense against malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog 5, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000423 (2009).

Oliver, K. M., Russell, J. A., Moran, N. A. & Hunter, M. S. Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 1803–1807, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0335320100 (2003).

Aliota, M. T. et al. The wMel Strain of Wolbachia Reduces Transmission of Chikungunya Virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 10, 28792, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004677 (2016).

Walker, T. et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature 476, 450, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10355 (2011).

Blagrove, M. S. C., Arias-Goeta, C., Di Genua, C., Failloux, A.-B. & Sinkins, S. P. A. Wolbachia wMel transinfection in Aedes albopictusis not detrimental to host fitness and inhibits chikungunya virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2152, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002152 (2013).

Moreira, L. A. et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042 (2009).

van den Hurk, A. F. et al. Impact of Wolbachia on infection with chikungunya and yellow fever viruses in the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1892, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001892 (2012).

Blagrove, M. S. C., Arias-Goeta, C., Failloux, A.-B. & Sinkins, S. P. Wolbachia strain wMel induces cytoplasmic incompatibility and blocks dengue transmission in Aedes albopictus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 255–260, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1112021108 (2012).

Mousson, L. et al. The native Wolbachia symbionts limit transmission of dengue virus in Aedes albopictus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6, e1989, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001989 (2012).

Mousoon, L. et al. Wolbachia modulates Chikungunya replication in Aedes albopictus. Mol. Ecol 19, 1953–1964, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04606.x (2010).

Tan, C. H. et al. wMel limits zika and chikungunya virus infection in a Singapore Wolbachia-introgressed Ae. aegypti strain, wMel-Sg. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 11, e0005496, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005496 (2017).

Frentiu, F. D. et al. Limited dengue virus replication in field-collected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 8, e2688, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002688 (2014).

Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., Walker, T. & O’ Neill, S. L. Wolbachia and the biological control of mosquito-borne disease. EMBO Rep 12, 508–518, https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2011.84 (2011).

Osei-Poku, J., Mbogo, C. M., Palmer, W. J. & Jiggins, F. M. Deep sequencing reveals extensive variation in the gut microbiota of wild mosquitoes from Kenya. Mol Ecol 21, 5138–5150, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05759.x (2012).

Rasgon, J. L. & Scott, T. W. An initial survey for Wolbachia (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) infections in selected California mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 41, 255–257, https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-41.2.255 (2004).

Ahmad, N. A., Vythilingam, I., Lim, Y. A. L., Zabari, N. Z. A. M. & Lee, H. L. Detection of Wolbachia in Aedes albopictus and their effects on chikungunya virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96, 148–156, https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0516 (2017).

Buck, M. et al. Bacterial associations reveal spatial population dynamics in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Sci. Rep 6, 22806, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22806 (2016).

Muturi, E. J., Ramirez, J. L., Rooney, A. P. & Kim, C.-H. Comparative analysis of gut microbiota of mosquito communities in central Illinois. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005377, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005377 (2017).

Minard, G. et al. Prevalence, genomic and metabolic profiles of Acinetobacter and Asaia associated with field-caught Aedes albopictus from Madagascar. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 83, 63–73, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01455.x (2012).

Zouache, K. et al. Bacterial diversity of field-caught mosquitoes, Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti, from different geographic regions of Madagascar. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 75, 377–389, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.01012.x (2011).

Hegde, S. et al. Microbiome interaction networks and community structure from laboratory-reared and field-collected Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito vectors. Front. Microbiol 9, 2160 (2018).

Rosso, F. et al. Reduced diversity of gut microbiota in two Aedes mosquitoes species in areas of recent invasion. Sci. Rep 8, 16091 (2018).

Weaver, S. C. Arrival of chikungunya virus in the New World: Prospects for spread and impact on public health. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2921, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002921 (2014).

Musso, D., Cao-Lormeau, V. M. & Gubler, D. J. Zika virus: following the path of dengue and chikungunya? Lancet 386, 243–244, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61273-9 (2018).

Gubler, D. J. Epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever as a public health, social and economic problem in the 21st century. Trends Microbiol. 10, 100–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02288-0 (2002).

Tabachnick, W. J. & Powell, J. R. A world-wide survey of genetic variation in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Genet. Res. 34, 215–229, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672300019467 (1979).

Eskildsen, G. A. et al. Maternal invasion history of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus into the Isthmus of Panama: Implications for the control of emergent viral disease agents. PLoS One 13, e0194874, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194874 (2018).

Pidiyar, V. J., Jangid, K., Patole, M. S. & Shouche, Y. S. Studies on cultured and uncultured microbiota of wild Culex quinquefasciatusmosquito midgut based on 16s ribosomal RNA gene analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 70, 597–603, https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2004.70.597 (2004).

Rani, A., Sharma, A., Rajagopal, R., Adak, T. & Bhatnagar, R. K. Bacterial diversity analysis of larvae and adult midgut microflora using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods in lab-reared and field-collected Anopheles stephensi-an Asian malarial vector. BMC Microbiol 9, 96, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-9-96 (2009).

Boissière, A. et al. Midgut microbiota of the malaria mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae and interactions with Plasmodium falciparuminfection. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002742, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002742 (2012).

Lindh, J. M., Terenius, O. & Faye, I. 16S rRNA gene-based identification of midgut bacteria from field-caught Anopheles gambiae sensu latoand A. funestus mosquitoes reveals new species related to known insect symbionts. Appl Env. Microbiol 71, 7212–7223, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.11.7217-7223.2005 (2005).

Wang, Y., Gilbreath, T. M., Kukutla, P., Yan, G. & Xu, J. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. PLoS One 6, e24767, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024767 (2011).

Minard, G., Mavingui, P. & Moro, C. V. Diversity and function of bacterial microbiota in the mosquito holobiont. Parasit. Vectors 6, 146, https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-146 (2013).

Moll, R. M., Romoser, W. S., Modrzakowski, M. C., Moncayo, A. C. & Lerdthusnee, K. Meconial peritrophic membranes and the fate of midgut bacteria during mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) metamorphosis. J Med Entomol 38, 29–32, https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-38.1.29 (2001).

Engel, P. & Moran, N. A. The gut microbiota of insects – diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 699–735, https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12025 (2013).

Douglas, A. E. The molecular basis of bacterial-insect symbiosis. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 3830–3837, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2014.04.005 (2014).

Alto, B. W., Lounibos, L. P., Mores, C. N. & Reiskind, M. H. Larval competition alters susceptibility of adult Aedes mosquitoes to dengue infection. Proc. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 275, 463–471, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2007.1497 (2008).

Gonçalves, C. M. et al. Distinct variation in vector competence among nine field populations of Aedes aegypti from a Brazilian dengue-endemic risk city. Parasit. Vectors 7, 320, https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-320 (2014).

Roundy, C. M. et al. Variation in Aedes aegypti mosquito competence for zika virus transmission. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J 23, 625, https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2304.161484 (2017).

Kilpatrick, A. M., Fonseca, D. M., Ebel, G. D., Reddy, M. R. & Kramer, L. D. Spatial and temporal variation in vector competence of Culex pipiens and Cx. restuans mosquitoes for West Nile virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 83, 607–613, https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0005 (2010).

Apte-Deshpande, A., Paingankar, M., Gokhale, M. D. & Deobagkar, D. N. Serratia odorifera a midgut inhabitant of Aedes aegypti mosquito enhances its susceptibility to dengue-2 virus. PLoS One 7, e40401, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040401 (2012).

McMeniman, C. J. et al. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 323, 141–144, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165326 (2009).

Fouda, M. A., Hassan, M. I., Al-Daly, A. G. & Hammad, K. M. Effect of midgut bacteria of Culex pipiens L. on digestion and reproduction. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 31, 767–780 (2001).

De Gaio, A. O. et al. Contribution of midgut bacteria to blood digestion and egg production in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) (L.). Parasit. Vectors 4, 105, https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-4-10 (2011).

Douglas, A. E. The microbial dimension in insect nutritional ecology. Funct Ecol 23, 38–47, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01442.x (2009).

Tchioffo, M. T. et al. Dynamics of bacterial community composition in the malaria mosquito’s epithelia. Front. Microbiol 6, 1500, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01500 (2015).

Douglas, A. E. Multiorganismal insects: Diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 60, 17–34, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020822 (2015).

Bravo, A., Gill, S. S. & Soberón, M. Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt toxins and their potential for insect control. Toxicon 49, 423–435, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.11.022 (2007).

Ponnusamy, L., Schal, C., Wesson, D. M., Arellano, C. & Apperson, C. S. Oviposition responses of Aedes mosquitoes to bacterial isolates from attractive bamboo infusions. Parasit. Vectors 8, 486, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1068-y (2015).

Zouache, K., Michelland, R. J., Failloux, A.-B., Grundmann, G. L. & Mavingui, P. Chikungunya virus impacts the diversity of symbiotic bacteria in mosquito vector. Mol Ecol 21, 2297–2309, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05526.x (2012).

Robinson, C. M. & Pfeiffer, J. K. Viruses and the microbiota. Annu. Rev. Virol 1, 55–69, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085550 (2014).

Hegde, S., Rasgon, J. L. & Hughes, G. L. The microbiome modulates arbovirus transmission in mosquitoes. Curr. Opin. Virol 15, 97–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2015.08.011 (2015).

Bian, G., Xu, Y., Lu, P., Xie, Y. & Xi, Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLOS Pathog. 6, e1000833, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000833 (2010).

Aliota, M. T., Peinado, S. A., Velez, I. D. & Osorio, J. E. The wMel strain of Wolbachia reduces transmission of Zika virus by Aedes aegypti. Sci. Rep 6, 28792, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004677 (2016).

Jiggins, F. M. The spread of Wolbachia through mosquito populations. PLOS Biol. 15, e2002780, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2002780 (2017).

Xi, Z., Khoo, C. C. H. & Dobson, S. L. Wolbachia establishment and invasion in an Aedes aegypti laboratory population. Science (80-.) 310, 326–328, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1117607 (2005).

Kitrayapong, P., Baimai, V. & O’Neill, S. L. Field prevalence of Wolbachia in the mosquito vector Aedes albopictus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 66, 108–111 (2002).

Zouache, K. et al. Persistent Wolbachia and cultivable bacteria infection in the reproductive and somatic tissues of the mosquito vector Aedes albopictus. PLoS One 4, e6388, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006388 (2009).

Joubert, D. A. et al. Establishment of a Wolbachia superinfection in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes as a potential approach for future resistance management. PLOS Pathog. 12, e1005434, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1005434 (2016).

Schmidt, T. L., Filipovic, I., Hoffmann, A. A. & Rasic, G. Fine-scale landscape genomics of Aedes aegypti reveals loss of Wolbachiatransinfection, dispersal barrier and potential for occasional long distance movement. Heredity. 120, 386–395, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-017-0039-9 (2017).

Poretsky, R., Rodriguez-R, L. M., Luo, C., Tsementzi, D. & Konstantinidis, K. T. Strengths and limitations of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing in revealing temporal microbial community dynamics. PLoS One 9, e93827, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093827 (2014).

Rueda, L. M. Pictorial keys for the identification of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) associated with dengue virus transmission. Zootaxa 589, 60 (2004).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 4516–4522, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000080107 (2011).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.f.303 (2010).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods 10, 57–59, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2276 (2013).

R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna, Austria (2018).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8, e61217, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061217 (2013).

Cáceres, M. De & Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90, 3566–3574, https://doi.org/10.1890/08-1823.1 (2009).

Baldo, L., Lo, N. & Werren, J. H. Mosaic nature of the Wolbachia surface protein. J. Bacteriol. 187, 5406–5418, https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.187.15.5406-5418.2005 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Panama’s Environmental Authority (Mi Ambiente, formerly ANAM) for supporting scientific collecting of mosquitoes in Panama. We thank the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) for administrative support and Instituto de Investigaciones Científicas y Servicios de Alta Tecnología (INDICASAT) for help in project logistics and technical guidance. We would like to thank the members of the Mosquito team (i.e., Alejandro Almanza, Elia Barraza, Vanessa Enríquez, Marcela Díaz, Evon Magnusson, Kaitlin Driesse and Jaime Cerro), as part of JRL research group, for their assistance in mosquito collections across Panama. This work was financed in part by STRI’s George E. Burch Fellowship Program and the Edward and Jeanne Kashian Family Foundation to KLB. In addition, the Secretariat for Science, Technology and Innovation of Panama (SENACYT), through the research grant IDDS15-047, the National System of Investigation (SNI), and the Zika project from the government of Panama, supported research activities by JRL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed by K.L.B., W.O.M. and J.R.L. and conducted by K.L.B., C.G.M., Y.C., K.S., W.O.M., J.R.R. and J.R.L. Intensive mosquito sampling collections were undertaken by K.L.B., C.G.M., J.R.R. and J.R.L. Morphological mosquito species identification was carried out by C.G.M., J.R.R. and J.R.L. K.L.B. performed data analysis and figure preparation and wrote the manuscript with contributions from C.G.M., Y.C., K.S., W.O.M., J.R.R. and J.R.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bennett, K.L., Gómez-Martínez, C., Chin, Y. et al. Dynamics and diversity of bacteria associated with the disease vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Sci Rep 9, 12160 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48414-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48414-8

This article is cited by

-

Overview of paratransgenesis as a strategy to control pathogen transmission by insect vectors

Parasites & Vectors (2022)

-

Microbial Diversity of Adult Aedes aegypti and Water Collected from Different Mosquito Aquatic Habitats in Puerto Rico

Microbial Ecology (2022)

-

Role of vertically transmitted viral and bacterial endosymbionts of Aedes mosquitoes. Does Paratransgenesis influence vector-borne disease control?

Symbiosis (2022)

-

Evaluation of a mosquito home system for controlling Aedes aegypti

Parasites & Vectors (2021)

-

The role of heterogenous environmental conditions in shaping the spatiotemporal distribution of competing Aedes mosquitoes in Panama: implications for the landscape of arboviral disease transmission

Biological Invasions (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.