Abstract

The aim of our study was to investigate a large cohort of overweight subjects consuming a homogeneous diet to identify the genetic factors associated with weight loss that could be used as predictive markers in weight loss interventions. We retrospectively recruited subjects (N = 788) aged over 18 years with a Body Mass Index (BMI) between 25 and 40 kg/m2 who were treated at our lipid unit for at least one year from 2008 to 2016, and we also recruited a control group (168 patients) with normal BMIs. All participants received counselling from a nutritionist that included healthy diet and physical activity recommendations. We genotyped 25 single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in 25 genes that were previously associated with obesity and calculated genetic scores that were derived from 25 SNVs. The risk allele in CADM2 showed a higher frequency in overweight and obese subjects than in controls (p = 0.007). The mean follow-up duration was 5.58 ± 2.68 years. Subjects with lower genetic scores showed greater weight loss during the follow-up period. The genetic score was the variable that best explained the variations in weight from the baseline. The genetic score explained 2.4% of weight change variance at one year and 1.6% of weight change variance at the end of the follow-up period after adjusting for baseline weight, sex, age and years of follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is one of the greatest public health problems that threatens both developed and non-developed countries. The European Health Survey indicates that in Spain, 18% of adults are obese and 37% are overweight, which is higher than the overall European obesity prevalence, which is estimated at 12%1. Obesity implies an excess of body fat and increases the risk of numerous comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), obstructive sleep apnoea, type 2 diabetes, different types of cancer and osteoarthritis, particularly in subjects with central deposition of adipose tissue2. It has been established that 4 million deaths worldwide can be attributed to overweight and obesity, and more than two-thirds of these deaths are due to CVD2. It is estimated that for each unit of increased body mass index (BMI), the risk of CVD increases by 8%3.

The therapeutic approach for overweight and obesity is based on lifestyle modification, prevention programmes, behavioural modification and, in extreme cases, the use of medication or bariatric surgery4. Life-style changes include the combination of diet modification, usually with a hypocaloric diet, and increased physical activity. However, there is a large interindividual variability in weight loss response, and not all subjects respond in the same way to the same intervention5,6. Although adherence is a major determinant in the response to a weight-loss intervention, a genetic component has also been recently demonstrated7,8. This is coherent considering that the development of obesity has a strong genetic component9 and that approximately 50–70% of variance in BMI is attributable to genetic differences10. The identification of genes that could determine the effectiveness of weight-loss strategies could lead to new approaches for the treatment and prevention of the rising pandemic of obesity.

Obesity is a heterogeneous and heritable disorder, which results from the combination among genetic susceptibility, epigenetics, metagenomics and environmental factors11. Monogenic syndromic forms of obesity, such as Alström syndrome, Bardet–Biedl syndrome and Cohen syndrome, have a very low frequency in the general population and are due to functional mutations in the ALMS1, BBS1 or BBS10 and COH1 genes, respectively12. Monogenic or oligogenic non-syndromic forms of obesity have been described in patients with homozygous or heterozygous compound loss-of-function mutations in genes that are part of the leptin melanocortin pathway: LEP, LEPR, POMC, PCSK1 and MC4R13. Reinehr et al. reported children who carrier MC4R mutations, which although they were able to lose weight with a lifestyle intervention, they had much greater difficulties in maintaining their weight loss. For instance, MC4R mutations led to reduced receptor function supporting the impact of these mutations on weight status14. However, in most cases, genetic susceptibility to obesity is due to polygenic component, which is produced by the concurrent presence of risk polymorphisms in various genes13. A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) led to the discovery more than 940 independent single nucleotide variants (SNVs), which are associated with body mass index (BMI)15. Based on the results of all GWASs, the FTO gene is viewed as the main contributor to polygenic obesity in the European population13.

Although many studies have addressed the genetic component of obesity in the last decade, the genes associated with a differential therapeutic response to weight-loss interventions have been studied much less frequently. We aimed to explore the genetic factors that could predict weight loss by studying a large cohort of subjects with BMI >25 kg/m2 who were following a homogeneous dietary intervention and exercise programme and who were followed up for several years.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This retrospective cohort study involved subjects attending the Lipid Unit at Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet in Zaragoza (Spain).

All unrelated subjects aged ≥18 years, of either sex, with a BMI between 25 and 40 kg/m2, who were followed-up ≥1 year and who visited the Lipid Unit at the Hospital Miguel Servet of Zaragoza from January 1st, 2008 to December 31st, 2016 were eligible for inclusion. The exclusion criteria included a personal history of malignancies, inflammatory bowel disease, bariatric surgery and taking anti-obesity drugs. Finally, 788 subjects with overweight or obesity were included (Fig. 1).

To study the SNVs associated with overweight and obesity, we randomly selected a control group of unrelated subjects with normal BMI (18.5–25 kg/m2) who attended the Lipid Clinic during the follow-up period. Finally, 168 control subjects were included.

All subjects signed an informed consent for a protocol that was previously approved by our local ethics committee (Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica of Aragón, Zaragoza). All the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and they were previously approved by our local ethics committee (Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica of Aragón, Zaragoza).

Clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical measurements

Baseline data were collected at the first visit to the unit. Weight, height, BMI and waist circumference were measured. We also assessed body composition by bioelectrical impedance (Tanita TBF 410 GS, Omron Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), as previously described16. Personal and family history of CVD and other comorbidities, such as hypertension and medication use, were recorded during the clinical interview. Plasma ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and serum samples were collected from all participants after 6 weeks without lipid-lowering drugs and after at least 10 hours of fasting. Total cholesterol and triglyceride levels were determined by standard enzymatic methods, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were measured by the oxidase method (UniCel DxC 800; Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, California, United States), as previously described17. LDL cholesterol was calculated using Friedewald’s formula. Serum glucose levels were assessed by glucose-oxidase method.

A baseline dietary assessment was performed using a previously published validated food frequency questionnaire. Food and nutrient intakes were calculated as frequency x nutrient composition of particularized portion sizes, in which frequencies were divided in 9 categories (never, 1–3 times a month, 1 time a week, 2–4 times a week, 5–6 times a week, 1 time a day, 2–3 times a day, 4–6 times a day and >6 times a day) for each food item. The total energy and nutrient intakes were calculated based on previously validated Spanish food composition Tables18.

Dietary intervention

All subjects received general dietary counselling based on dietary recommendations for overweight and obesity19 and lipid profile management according to international guidelines20. The dietary advice focused on increasing the intake of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, polyunsaturated fatty acids, low-fat dairy products, lean meat and fish and decreasing the consumption of saturated fatty acids, red and processed meat, soft drinks, alcohol and other sweetened products. Participants were instigated to increase their physical activity levels in consideration of their physical condition. All recommendations were provided by two expert dietitians at baseline, and they were reinforced at each follow-up visit. Each participant’s caloric prescription was represented by a deficit of 300 kcal/day, which has been calculated from energy intakes estimated. The energy intakes were estimated by multiplying the activity factor (energy expenditure for various activities established by the WHO) by the resting energy expenditure calculated with the Harris-Benedict equation.

Follow-up

All subjects attended 3 follow-up visits during the first year and one follow-up annually thereafter. These follow-up visits included clinical, anthropometric, and lipid profile measurements and a reinforcement of the lifestyle recommendations. New diagnoses of malignancies, inflammatory bowel disease, or bariatric surgery were also exclusion criteria for the follow-up visits. Weight change was calculated using the next formula: the difference between the baseline weight and the final weight, divided by the baseline weight. Glucose change was calculated using the same formula: the difference between baseline glucose and final glucose, divided by baseline glucose. We classified the subjects into 3 categories according to weight loss: subjects who lost more than 2% of their body weight, subjects who gained more than 2% of their body weight and subjects who remained within 2% of their body weight. We chose these cut-off points to create groups with a relatively homogeneous sample size. Furthermore, we performed a subanalysis using 5% instead of 2% as a cut-off value, and this classification was used at the end of the first year and at the end of the follow-up period.

Genetic analysis

Whole blood genomic DNA was isolated using standard methods. The SNV selection was based on previous associations with obesity in at least two independent GWASs21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 and a greater than 5% frequency of the risk allele in the general population. These included the following loci: BDNF, CADM2, FANCL, FLJ35779, FTO, GNPDA2, HOXC13, KCTD15, LRP1B, LRRN6C, LY86, MAP2K5, NFE2L3, NRXN3, PRKD1, RBJ, RPL27A, RSPO3, SEC. 16B, SH2B1, TFAP2B, TMEM18, TNNI3K, VEGFA and ZNRF3-KREMEN1. SNVs were genotyped in all subjects at the same time with TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher) using standard methods. The APOE genotype was determined by DNA sequencing of exon 4, as previously described34. We defined the risk allele as the allele that is associated with obesity according to the GWASs that were used for SNV selection.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (Chicago, Illinois, United States). The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. The distribution of the variables was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Quantitative variables with a normal distribution are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and were analysed by the Student t test. Qualitative variables are expressed as percentages and were analysed by the chi-squared test. To compare the genotype and allele frequency of the genetic variants between cases and controls, we used the chi-squared test. To compare the variations in BMI throughout the follow-up period we used the paired t-test. The association of weight change with SNVs and genetic score (see below) was analysed with a linear regression model that was adjusted for baseline weight, sex, age, follow-up time, smoking status, alcohol consumption and daily consumption of vegetables, proteins, fruits, dairy products, olive oil, fish and sweets. To determine what type of model (additive, dominant or recessive) was the best, we calculated the Akaike information criterion (AIC = 2k + ln (L), where K is the number of parameters in the model and L is the likelihood) using a binary logistic regression models (yes/no) with weight loss during the follow-up as the dependent variable (Supplemental Table 1). Different regression models were used to test each inheritance. Genotypes were recorded as follows. The homozygotes for the risk allele (MM), heterozygotes (Mm), and homozygotes for the protective allele (mm) were coded to a continuous numeric variable for the genotype (as 0, 1 and 2 respectively; additive model). A dominant model was defined as contrasting genotypic groups MM + Mm vs. mm, and the recessive model was defined as contrasting genotypic groups MM vs.Mm + mm.

The baseline excess body weight, the weight that is above a normal BMI ≤25 kg/m2, and loss of body weight were analysed according to quartiles by the weighted genetic score (see below) using the ANOVA test.

The association of glucose change with SNVs was analysed by a linear regression model using the glucose change throughout the follow-up period as a dependent variable and adjusting the model for weight change throughout the follow-up, years of follow-up, age, sex and all SNVs. This analysis was performed after excluding subjects with type 2 diabetes.

Genetic score

The genetic score was calculated for each subject by using the sum of the presence (for dominant or recessive model, as appropriate) of the risk genotypes in the 25 SNVs studied.

Results

This study was conducted with a cohort that included 788 overweight patients with BMI >25 kg/m2 who completed at least one year of follow-up and 168 controls with BMI <25 kg/m2. The overweight patients were older, included a higher percentage of men and had lower HDL cholesterol levels and a higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension than the controls. No differences in total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol or APOE genotype were found between the groups (Table 1).

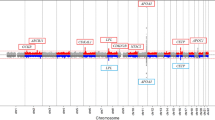

The frequency of the risk allele for obesity for each of the 25 SNVs was compared between the overweight patients and controls. The risk allele frequency of one SNV in CADM2 was significantly higher in the overweight patients than in the controls (p = 0.007), and two risk alleles of SNVs in KCTD15 and LY86 genes were significantly lower in the overweight patients than in the controls (p = 0.022 and p = 0.047, respectively). The risk allele frequency of one SNV in the GNPDA2 gene was significantly higher in the overweight patients than in the 1000 Genomes Project database, and the risk allele frequency of one SNV in the RBJ gene was significantly lower in the overweight patients than in the 1000 Genomes Project database (p = 0.014 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Supplemental Table 2). Furthermore, the frequency of the risk allele for obesity for each of the 25 SNVs was compared between the overweight and obese subjects separately and the controls. The risk allele frequency of the SNV in the CADM2 gene was significantly higher in the obese and overweight subjects than in the controls (p = 0.014 and p = 0.001, respectively). The risk allele frequency of SNV in the KCTD15 gene was significantly lower in overweight subjects than in controls (p = 0.019).

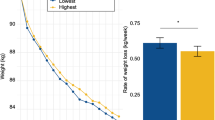

The mean follow-up period was 5.58 ± 2.68 years (range 1.5–10 years). The dietary intervention resulted in a significant reduction of 0.68% of body weight during the follow-up (p = 0.003). Figure 2 indicates the body mass index values at baseline and during the follow-up in the entire population. The dietary intervention resulted in a significant reduction of 1.11% of the BMI on average during the first year of the intervention (p < 0.001). In the following years, the subjects progressively gained weight, and in the sixth year, they surpassed the baseline BMI. However, there were no significant differences in these increases in BMI, except for the interval from the second to the third year (p < 0.001) (Supplemental Table 3). Table 2 compares the baseline values and the variation in clinical and biochemical characteristics among the groups based on weight change during follow-up. Subjects who lost more than 2% of their body weight had higher baseline body weight, fat mass, abdominal visceral fat, and glucose and lower baseline cholesterol than subjects who gained more than 2% of their body weight. All subjects improved their lipid profiles during the follow-up due to lipid lowering drugs, without significant differences among the weight-change groups, except for the difference in HDL cholesterol, which increased more in subjects who lost more than 2% of their body weight. Supplemental Table 4 shows the genotype frequencies of SNVs according to the weight-change groups. Only one SNV, r10150332 in the NRXN3 gene, showed significant differences between the groups (p = 0.037). Subjects who gained more than 2% weight were more frequently homozygous for the risk allele.

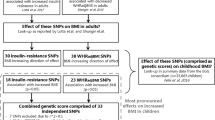

The association between weight change and each SNV was analysed by a linear regression analysis. We categorized each SNV for recessive and dominant models for the risk allele. Five SNVs (rs7359397, rs2112347, rs29941, rs10150332, rs4929949) were significantly associated with weight change. The first one (rs7359397) was compatible with a dominant model and the rest were compatible with recessive models based on their effects. The SNVs rs2112347 and rs10150332 were significantly associated with weight change in the first year, and the other 3 SNVs were significantly associated with weight change at the end of the follow-up.

In addition, we studied the impact of all 25 SNVs included in the genetic score on weight change in the first year and during the follow-up. The percentage of weight change explained by baseline weight and the genetic score adjusted for age, gender and smoking habit was 10.1%. The genetic score explained 2.4% of weight variation, making the genetic score the variable that best explains the weight variation after baseline weight (Table 3). The percentage of weight change at the end of follow-up explained by baseline weight and genetic score adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, and follow-up duration was 8.8%. In this case, the genetic score explained 1.6% of the weight variation (Table 4). In addition, according to the U-shape relationship between time of intervention and weight loss, shown in Fig. 2, we studied the impact of the genetic score on weight loss after the first four years of the intervention. The percentage of weight change during the first four years explained by baseline weight, genetic score, and smoking status adjusted for age and sex was 12.2%. The genetic score explained 2.1% of the weight variation (Supplemental Table 5). The genetic score was significantly higher in subjects who gained more than 2% weight at the end of the follow-up than subjects who lost more than 2% weight (p < 0.001). To further investigate the value of the weighted genetic score, we selected subjects with changes in body weight >5%. This selection further amplified the differences in the weighted genetic score in subjects who gained over 5% of their body weight vs subjects who lost more than 5% of their body weight (scores: 18.36 vs 22.28, respectively, p < 0.001) (Table 5).

To analyse the change in excess weight body independently of SNVs, we studied the body weight loss according to genetic score quartiles. There was no significant difference between the baseline excess body weight based on the genetic score quartile (p = 0.262). However, there were significant differences in the loss of excess body weight, in which the subjects in the lower quartile had a significantly greater loss of excess weight (p < 0.001) (Table 6).

Considering the close relationship between weight and glucose, we studied the impact of the studied SNVs on glucose changes at the end of follow-up. We calculated the glucose change associated with each SNV with univariate linear regression models adjusted for age, weight change, follow-up duration, and sex. Two SNVs, rs9491696 in a recessive model and rs7359397 in a dominant model for their risk alleles, showed a statistically significant association with glucose change (p = 0.042 and p = 0.040). Weight change during the follow-up, together with follow-up duration, sex, age and these SNPs, explained up to 2.9% of the variance in fasting glucose change. Both SNVs explained 0.8% of the variance in fasting glucose change (Supplemental Table 6).

Discussion

Obesity is a multifactorial disorder that has a genetic component but is also influenced by many environmental factors. The first genetic studies on obesity involved monogenic and extreme obesity syndromes, and the researchers focused their attention on the dysfunction of the leptin-hypothalamus pathway35. More recently, GWAS have allowed for the identification of many loci involved in interindividual weight variation that are associated with the most common expressions of obesity15. These association studies have contributed to the identification of new genes that are mechanistically involved in the pathophysiology of obesity36. In this study, we found an association between short- and long-term weight loss and genetic predisposition in a Spanish cohort. Our findings showed that subjects with higher genetic scores calculated from selected SNVs had greater weight gain, both in the short and long term, than subjects with lower genetic scores.

Among the 25 SNVs that we analysed that were previously associated with obesity, the allele frequencies of three of them, rs13078807 in the CADM2 gene, rs29941 in the KCTD15 gene, and rs1294421 in the LY86 gene, were significantly different at baseline between the overweight patients and the controls. However, only rs13078807 in the CADM2 gene showed a significantly higher prevalence of the risk allele in the overweight patients than in the controls. CADM2 is a gene that encodes a mediator of synaptic signalling that is enriched in the brain, and CADM2 appears to be associated with BMI in GWASs37,38. A previous study showed that the risk allele variant rs13078960 is associated with increased CADM2 expression in the human hypothalamus. Deletion of Cadm2 in obese mice reduce the adiposity tissue, fasting glucose levels and improved insulin sensitivity. Therefore, CADM2 plays a role as a potent regulator of systemic energy homeostasis39.

Among the 5 common genetic variants that were significantly associated with weight change, 2 of them, rs2112347 in the FLJ35779 gene and rs10150332 in the NRXN3 gene, were associated with weight change in the first year. At present, there is no information on the putative mechanism associating the FLJ35779 gene with obesity27. In contrast, the NRXN3 gene encodes NRXN proteins, which are located in presynaptic space and are proposed to interact with postsynaptic neuroligins. The NRXN3 gene has been previously associated with central nervous system disorders and obesity, so its role in obesity could be a result of alterations to the nervous system23,40. The SNV rs29941 in the KCTD15 gene, rs4929949 in the RPL27A gene and rs7359397 in the SH2B1 gene showed an association with weight modification during the follow-up period. The SH2B1 gene encodes an adaptor protein which increases signalling in the Janus kinase signal transducer and activator (JAK-STAT) pathway downstream of the leptin receptor27. Previous studies have demonstrated that natural loss-of-function mutations in the SH2B1 gene in humans lead to both elevated food intake and severe obesity associated with leptin resistance27. KCTD15 is associated with TFAP2B, and both of them genes have been linked to obesity in GWASs, indicating a possible physical interaction in vivo. Previous studies have suggested that KCTD15 and TFAP2B could play a role in the pathophysiology of obesity due to the deregulation of glucose and increased peripheral resistance to insulin41. RPL27A encodes the ribosomal protein L27A, which has been related with the obesity in humans, although the molecular pathway remains unknown41.

The genetic score that we calculated from the sum of the 25 SNVs that were previously associated with obesity was significantly higher in patients with greater weight gain, although the weight variation explained by the score was small (2.4%). These percentage are similar to those provided by scores developed in other studies, in which the authors indicated that all BMI-associated variants combined explained 2.7% of the variation in BMI38. However, our genetic score is based on 25 SNVs; in contrast, the genetic score developed by Locke et al. was based on 97 SNVs38. Nevertheless, these percentages are far from the 70% of the inter-individual differences in body weight that are attributable to genetic differences between individuals42. Unknown genes involved in obesity, non-genetic familial influences and/or the interactions of genetic and environmental factors are probably important factors to explain this discrepancy.

Finally, we found two SNVs, rs9491696 in the RSPO3 gene and rs7359397 in the SH2B1 gene, that were associated with fasting glucose changes during the follow-up period. Both SNVs explained 2% of the glucose change when assessed together with weight change during the follow-up period. The expression of SH2B1 occurs mostly in the pancreas as well as the liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Besides, SH2B1 plays a major role in insulin signalling, as might be expected given that the JAK-STAT signalling pathway is also an intracellular signalling pathway used by the insulin receptor27. However, RSPO3 has only been previously associated with BMI, and its molecular pathway remains unknown43.

Our study has some limitations: the dietary intervention, including general counselling, was not very intense and the follow-up period included only one visit per year. However, the aim of our study was not to achieve great reductions in body weight but to study the genetic influences in subjects with overweight or obesity who were following the same dietary recommendations. The overweight and obese participants were recruited from a lipid clinic, which could be a bias in the estimation of the epidemiological or genetic influences in our study44. However, lifestyle is especially important in these patients, and new studies on this topic in the general population would be necessary to extrapolate our results to a healthy population. We genotyped 25 SNVs, and there are at least 940 known SNVs that are associated with BMI. However, we observe that the variance explained by our score is similar to that explained by Locke et al. with their score based on all 97 SNVs.

In conclusion, the genotyping of 25 SNVs that were previously associated with obesity in a grand cohort of subjects with overweight and obesity allowed for the development of a genetic score that explained 2.4% of weight change during the follow-up period. In addition, subjects with lower genetic scores showed increased weight loss during the follow-up period. However, these percentages must increase to use this genetic score as a predictive marker of weight loss. Further research is needed to fully understand the role of genetics and epigenetics in obesity, which could lead to better management and prevention of this pandemic.

References

GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 13–27 (2017).

González-Muniesa, P. et al. Obesity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 3, 17034 (2017).

Kenchaiah, S. et al. Obesity and the risk of heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 305–313 (2002).

Lavie, C. J. et al. Healthy Weight and Obesity Prevention: JACC Health Promotion Series. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 1506–1531 (2018).

Reinehr, T. et al. Two-year follow-up in 21,784 overweight children and adolescents with lifestyle intervention. Obes. Silver Spring Md 17, 1196–1199 (2009).

Espeland, M. A. et al. Describing patterns of weight changes using principal components analysis: results from the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) research group. Ann. Epidemiol. 19, 701–710 (2009).

McCaffery, J. M. et al. Human cardiovascular disease IBC chip-wide association with weight loss and weight regain in the look AHEAD trial. Hum. Hered. 75, 160–174 (2013).

McCaffery, J. M. et al. FTO predicts weight regain in the Look AHEAD clinical trial. Int. J. Obes. 2005 37, 1545–1552 (2013).

Arner, P. Hunting for human obesity genes? Look in the adipose tissue! Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 24(Suppl 4), S57–62 (2000).

Allison, D. B. et al. The heritability of body mass index among an international sample of monozygotic twins reared apart. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 20, 501–506 (1996).

Pigeyre, M., Yazdi, F. T., Kaur, Y. & Meyre, D. Recent progress in genetics, epigenetics and metagenomics unveils the pathophysiology of human obesity. Clin. Sci. Lond. Engl. 1979 130, 943–986 (2016).

Kaur, Y., de Souza, R. J., Gibson, W. T. & Meyre, D. A systematic review of genetic syndromes with obesity. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 18, 603–634 (2017).

Stryjecki, C., Alyass, A. & Meyre, D. Ethnic and population differences in the genetic predisposition to human obesity. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 19, 62–80 (2018).

Reinehr, T. et al. Lifestyle intervention in obese children with variations in the melanocortin 4 receptor gene. Obes. Silver Spring Md 17, 382–389 (2009).

Yengo, L. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ∼700000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 3641–3649 (2018).

Mateo-Gallego, R., Bea, A. M., Jarauta, E., Perez-Ruiz, M. R. & Civeira, F. Age and sex influence the relationship between waist circumference and abdominal fat distribution measured by bioelectrical impedance. Nutr. Res. N. Y. N 32, 466–469 (2012).

Lamiquiz-Moneo, I. et al. ABCG5/G8 gene is associated with hypercholesterolemias without mutation in candidate genes and noncholesterol sterols. J. Clin. Lipidol. 11, 1432–1440.e4 (2017).

de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C., Ruiz, Z. V., Bes-Rastrollo, M., Sampson, L. & Martinez-González, M. A. Reproducibility of an FFQ validated in Spain. Public Health Nutr. 13, 1364–1372 (2010).

Jensen, M. D. et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 129, S102–138 (2014).

Stone, N. J. et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 129, S1–45 (2014).

Poveda, A., Ibáñez, M. E. & Rebato, E. Common variants in BDNF, FAIM2, FTO, MC4R, NEGR1, and SH2B1 show association with obesity-related variables in Spanish Roma population. Am. J. Hum. Biol. Off. J. Hum. Biol. Counc. 26, 660–669 (2014).

Zhao, J. et al. Role of BMI-associated loci identified in GWAS meta-analyses in the context of common childhood obesity in European Americans. Obes. Silver Spring Md 19, 2436–2439 (2011).

Wang, K. et al. A genome-wide association study on obesity and obesity-related traits. PloS One 6, e18939 (2011).

Albayrak, Ö. et al. Common obesity risk alleles in childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Psychiatr. Genet. 162B, 295–305 (2013).

Goumidi, L., Cottel, D., Dallongeville, J., Amouyel, P. & Meirhaeghe, A. Effects of established BMI-associated loci on obesity-related traits in a French representative population sample. BMC Genet. 15, 62 (2014).

Goodarzi, M. O. Genetics of obesity: what genetic association studies have taught us about the biology of obesity and its complications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol., https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30200-0 (2017).

Speakman, J. R. Functional analysis of seven genes linked to body mass index and adiposity by genome-wide association studies: a review. Hum. Hered. 75, 57–79 (2013).

Schleinitz, D., Böttcher, Y., Blüher, M. & Kovacs, P. The genetics of fat distribution. Diabetologia 57, 1276–1286 (2014).

Burgdorf, K. S. et al. Association studies of novel obesity-related gene variants with quantitative metabolic phenotypes in a population-based sample of 6,039 Danish individuals. Diabetologia 55, 105–113 (2012).

Nettleton, J. A. et al. Gene × dietary pattern interactions in obesity: analysis of up to 68 317 adults of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 4728–4738 (2015).

Liu, C.-T. et al. Genome-wide association of body fat distribution in African ancestry populations suggests new loci. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003681 (2013).

Wang, H.-J. et al. Association of common variants identified by recent genome-wide association studies with obesity in Chinese children: a case-control study. BMC Med. Genet. 17, 7 (2016).

Strawbridge, R. J. et al. Effects of Genetic Loci Associated with Central Obesity on Adipocyte Lipolysis. PloS One 11, e0153990 (2016).

Solanas-Barca, M. et al. Apolipoprotein E gene mutations in subjects with mixed hyperlipidemia and a clinical diagnosis of familial combined hyperlipidemia. Atherosclerosis 222, 449–455 (2012).

Waalen, J. The genetics of human obesity. Transl. Res. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 164, 293–301 (2014).

Wolff, G. L. Obesity as a pleiotropic effect of gene action. J. Nutr. 127, 1897S–1901S (1997).

Speliotes, E. K. et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat. Genet. 42, 937–948 (2010).

Locke, A. E. et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 518, 197–206 (2015).

Yan, X. et al. Cadm2 regulates body weight and energy homeostasis in mice. Mol. Metab., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2017.11.010 (2017).

Hu, X. et al. Association study of NRXN3 polymorphisms with schizophrenia and risperidone-induced bodyweight gain in Chinese Han population. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 43, 197–202 (2013).

Williams, M. J., Almén, M. S., Fredriksson, R. & Schiöth, H. B. What model organisms and interactomics can reveal about the genetics of human obesity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 69, 3819–3834 (2012).

Elks, C. E. et al. Variability in the heritability of body mass index: a systematic review and meta-regression. Front. Endocrinol. 3, 29 (2012).

Horikoshi, M. et al. Discovery and Fine-Mapping of Glycaemic and Obesity-Related Trait Loci Using High-Density Imputation. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005230 (2015).

Wang, J. & Shete, S. Estimation of odds ratios of genetic variants for the secondary phenotypes associated with primary diseases. Genet. Epidemiol. 35, 190–200 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Cecilia Bennett for her English editorial assistance. Genetic analyses were performed in the Sequencing and Functional Genomics Facility of Servicios Científico Técnicos of CIBA (IACS-Universidad de Zaragoza), Zaragoza, Spain. Dr. Laclaustra’s research activity is funded by ARAID (Aragón Investigación y Desarrollo). This study was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness PI15/01983, PI13/02507, PI12/01321, CIBERCV, and the Cuenca Villoro Foundation. These projects are co-financed by Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) of the European Union “A way to make Europe”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.L.M., A.M.B., S.P.C., R.M.G., V.M.B. and B.D.G. conducted the research. I.L.M., M.L. and R.M.G. analysed the data. I.L.M. and R.M.G. contributed to the writing of the article. F.C. and A.C. contributed to the recruitment protocol and research design and are primarily responsible for the final content. All authors participated in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the drafting of the article or critical revision; and in final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamiquiz-Moneo, I., Mateo-Gallego, R., Bea, A.M. et al. Genetic predictors of weight loss in overweight and obese subjects. Sci Rep 9, 10770 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47283-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47283-5

This article is cited by

-

Impact of polygenic score for BMI on weight loss effectiveness and genome-wide association analysis

International Journal of Obesity (2024)

-

Race/ethnicity-associated blood DNA methylation differences between Japanese and European American women: an exploratory study

Clinical Epigenetics (2021)

-

Genetic Polymorphisms, Mediterranean Diet and Microbiota-Associated Urolithin Metabotypes can Predict Obesity in Childhood-Adolescence

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Obesity Genomics and Metabolomics: a Nexus of Cardiometabolic Risk

Current Cardiology Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.