Abstract

The quality of parental care received during development profoundly influences an individual’s phenotype, including that of maternal behavior. We previously found that female rats with a history of maltreatment during infancy mistreat their own offspring. One proposed mechanism through which early-life experiences influence behavior is via epigenetic modifications. Indeed, our lab has identified a number of brain epigenetic alterations in female rats with a history of maltreatment. Here we sought to investigate the role of DNA methylation in aberrant maternal behavior. We administered zebularine, a drug known to alter DNA methylation, to dams exposed during infancy to the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources, and then characterized the quality of their care towards their offspring. First, we replicate that dams with a history of maltreatment mistreat their own offspring. Second, we show that maltreated-dams treated with zebularine exhibit lower levels of adverse care toward their offspring. Third, we show that administration of zebularine in control dams (history of nurturing care) enhances levels of adverse care. Lastly, we show altered methylation and gene expression in maltreated dams normalized by zebularine. These findings lend support to the hypothesis that epigenetic alterations resulting from maltreatment causally relate to behavioral outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infant experiences with a caregiver have lifelong behavioral consequences and the mechanisms through which these early-life experiences are capable of inducing long-term effects on phenotype continue to be elucidated1,2,3,4,5. Epigenetic alterations offer one potential mechanism through which experiences in infancy can perpetuate their consequences throughout the lifespan2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. For example, experiencing adverse maternal care induces both transient and long-term modifications to the epigenome2,9,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation and posttranslational histone modifications, are capable of influencing gene expression without altering the underlying genomic sequence. DNA methylation, or the addition of methyl groups to cytosine residues on DNA, typically represses the expression of genes24,25,26. These epigenetic modifications can have functional implications by altering levels of gene expression and in turn protein products, in specific brain regions that control behavior.

Maternal behavior is a complex behavior requiring the recruitment of multiple brain regions including the nucleus accumbens (NAC)27,28,29, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST)30,31,32,33,34,35, ventral tegmental area (VTA)34,36,37,38, prefrontal cortex (PFC)38,39,40, amygdala41,42,43,44,45, and medial preoptic area (MPOA)30,35,39,46,47. In this circuit, hormones including estrogen act on the MPOA to stimulate maternal behavior47,48. The MPOA is then primed to become active in response to pup stimuli. The PFC and amygdala are involved in processing sensory information, such as pup scent, which elicit maternal responsiveness49. The MPOA in turn projects to the VTA, which provides dopaminergic input to the NAC. This projection is important for the rewarding component of pup interactions50. Dysregulation within this circuitry can lead to altered or impaired maternal responsiveness49, and epigenetic modifications within this circuit are one potential mechanism through which dysregulation could occur. Indeed, experience-driven alterations in DNA methylation in maternal circuitry can influence maternal behavior via altered functioning in these brain regions7,51.

Our lab employs the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources, a validated rodent model of caregiver maltreatment52. The scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources is a within litter paradigm whereby 1/3 of the litter is left in the home cage with the biological dam, 1/3 of the litter is removed from the home cage and placed in another environment for 30 minutes with a dam that provides nurturing care, and the remaining 1/3 of the litter is removed from the home cage and placed in another environment for 30 minutes with a dam that provides adverse care. Infant rats are exposed to these caregiving conditions daily during the first seven days of life. Utilizing this model, our lab has previously identified altered gene expression and DNA methylation in some of the brain regions controlling maternal behavior2,18,53. Coinciding with altered patterns of DNA methylation, our lab has likewise found aberrant maternal behavior (more adverse and less nurturing care) in females subjected to maltreatment2, consistent with studies in humans finding disrupted maternal behavior (e.g. increased hostility and reduced warmth toward children, impaired mother-child bonding, and increased use of physical punishment) in women that experienced childhood abuse54,55,56,57,58,59. Maternal behavior is an intergenerational behavior, as the quality of maternal care a female experiences influences the quality of care she will give her own offspring2,58,60,61,62. Therefore, it is important to establish the neurobiological underpinnings of aberrant maternal behavior and explore treatments that can improve maternal behavior to prevent the perpetuation of poor maternal care across generations.

In previous work, we demonstrated the ability of the epigenome-altering drug, zebularine, to reverse maltreatment-induced DNA methylation and expression of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf) gene in the adult PFC2 and alter some adult behavioral outcomes63. Based upon this, in the current study, we sought to assess the ability of zebularine to rectify consequences of maltreatment on maternal behavior when administered to adult dams. To examine the neurobiological underpinnings of maternal behavior deficits in maltreated animals, we assayed DNA methylation and gene expression within the MPOA due to this brain region’s critical role in maternal behavior30,34,35,44,49.

Results

Infant manipulations

A one-way ANOVA performed on adverse behaviors observed across our infant manipulations revealed a main effect of infant condition (F(2,12) = 20.17, p = 0.0001, Cohen’s d = 3.176; Fig. 1). Post-hoc comparisons showed that animals in the maltreatment condition experienced significantly more adverse behaviors relative to those in the normal (p = 0.0013) and cross-foster (p = 0.0002) care conditions. We did not find any differences in the levels of adverse care between the cross-foster and normal care conditions (p = 0.4145). These results are consistent with previous reports employing the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources1,2,18. These data validate the efficacy of our model to experimentally induce an adverse caregiving environment.

Pups in the maltreatment condition incurred a higher prevalence of adverse behaviors from the caregiver relative to pups placed in the cross-foster and normal maternal care conditions. These data are presented as percentage of occurrence of behavior in 5-minute time bins across the 30 minute behavioral recordings (averaged across the 7 days). n = 5 litters; **Denotes p < 0.01, comparison is the maltreatment group versus both the normal care and cross-foster care groups. NMC = normal maternal care; CFC = cross-foster care; MAL = maltreatment.

Trivers–willard effect

To examine the presence of the Trivers–Willard effect, which predicts that females with a history of stress will have a higher female:male pup ratio64, pups were sexed and counted. We did not find a significant difference in the litter size (F(2,65) = 0.5636, p = 0.5719, Fig. 2A) or female:male pup ratio (F(2,65) = 1.34, p = 0.2691, Fig. 2B) as a result of infant condition. These data indicate that within the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources as employed here, dams with a history of maltreatment do not show altered litter compositions compared to control dams.

Adult maternal behavior

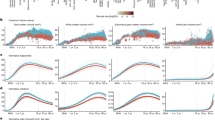

No significant differences in maternal behavior were found between subjects in the cross-foster and normal maternal care vehicle groups (t(19) = 0.5541, p = 0.5927) or the cross-foster and normal maternal care zebularine groups (t(21) = 1.071, p = 0.2962), therefore the nurturing care vehicle groups were collapsed and the nurturing care zebularine groups were collapsed to increase statistical power. A two-way ANOVA performed on the number of adverse behaviors performed by dams demonstrated an infant condition X drug treatment interaction (F(1,60) = 8.036, p = 0.0062, Cohen’s d = 1.126, Fig. 3). Consistent with our previous finding2, post-hoc analyses revealed that females with a history of maltreatment (i.e. maltreatment-vehicle group) performed more adverse behaviors toward their offspring relative to animals with a history of nurturing care (i.e. nurturing-vehicle group) (t(29) = 2.315, p = 0.0279). There was a significant difference between the maltreatment group administered zebularine versus the vehicle-treated maltreatment group, suggesting that zebularine rescued maltreatment-induced aberrations in maternal behavior (t(18) = 2.466, p = 0.0239).

Animals with a history of maltreatment exhibited more adverse caregiving behaviors toward their pups as compared to dams without a history of maltreatment (i.e. dams with a history of nurturing infant care). Treatment with zebularine significantly reduced levels of adverse behavior exhibited toward offspring in previously maltreated dams. Zebularine treatment disturbed behavior in dams without a history of maltreatment such that drug-treated dams exhibited higher levels of adverse behavior toward offspring relative to vehicle-treated controls. n = 10–23/group; *denotes p < 0.05, comparisons indicated by black lines.

Treatment with zebularine disrupted maternal care in females without a history of maltreatment (i.e. controls), such that drug-treated controls showed numerically more adverse behaviors than their vehicle-treated counterparts (t(42) = 2.006, p = 0.0513). No significant differences were found between the zebularine-treated dams with a history of nurturing care versus the maltreated dams given vehicle (p = 0.8927), or the vehicle-treated nurturing care group versus the zebularine-treated maltreatment group (p = 0.1332). Taken together, these data indicate that zebularine normalizes maternal behavior in dams with a history of maltreatment while disturbing maternal behavior in dams with a history of nurturing care in infancy.

DNA methylation

No significant differences in average levels of methylation were detected between control vehicle groups (cross-foster vs. normal care, p = 0.9407) or control zebularine groups (cross-foster vs. normal care, p = 0.4081), thus control groups administered the same treatment were collapsed. Analysis of Bdnf methylation of exon IV DNA revealed a significant infant condition X drug interaction (F(1,63) = 4.088, p = 0.0474, Cohen’s d = 0.77, Fig. 4A). Post-hoc analyses revealed that animals with a history of maltreatment displayed significantly reduced levels of methylation relative to control animals delivered vehicle (p = 0.034). However, maltreated animals administered zebularine did not show different levels of methylation relative to controls (p = 0.3053), suggesting that zebularine was able to normalize methylation levels in animals with a history of maltreatment. While numerically different levels of methylation were observed between control animals administered zebularine as compared to vehicle, this relationship did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0715).

DNA methylation of Bdnf exon IV (average levels across the 11 CG sites represented in panel A, site-specific levels represented in panel B) was reduced in vehicle-treated animals with a history of maltreatment. Administration of zebularine in adulthood normalized DNA methylation in these dams. n = 10–23/group; *Denotes p < 0.05, comparison is the maltreatment vehicle group versus the control vehicle group.

Two-way ANOVAs were performed on each of the 11 CG sites sequenced for Bdnf IV (Fig. 4B). There was an infant condition X drug interaction at CG site 3 (F(1,63) = 4.13, p = 0.0464, Cohen’s d = 0.774), with post-hoc analyses revealing that animals with a history of maltreatment displayed significantly reduced levels of methylation relative to control animals delivered vehicle (p = 0.0312). There was also an infant condition X drug interaction at CG sites 4 (F(1,63) = 4.153, p = 0.0458, Cohen’s d = 0.776) and 11 (F(1,62) = 4.043, p = 0.0487, Cohen’s d = 0.773), however post hoc analyses failed to meet significance for either site.

We also conducted an assay using a partial set of the same DNA samples (n = 6–14, randomly chosen) to assess global 5mc levels in the MPOA (Fig. 5). There were no effects of drug treatment (F(1,36) = 0.06781, p = 0.796), infant condition (F(1,36) = 1.1323, p = 0.2577), nor an interaction effect (F(1,36) = 0.07113, p = 0.7912).

Gene expression

Control groups administered vehicle were collapsed and control groups administered zebularine were collapsed, as no significant group differences in gene expression were found (p’s > 0.05). No significant effects of drug treatment, infant condition, nor interactions were found for expression of fos, DNMT1, DNMT3a, Bdnf exons I and IX, Drd1, Oprm, Oxtr, Crfr1, or GR (p’s > 0.05, Table 1). For DNMT1, an ANOVA revealed a marginally significant main effect of infant condition (F(1,61) = 3.903, p = 0.0527, Cohen’s d = 0.753), however, post-hoc analyses failed to meet significance (nurturing care versus maltreatment vehicle groups, p = 0.0852). With regard to Bdnf IV expression, a two-way ANOVA revealed a significant infant condition X drug interaction (F(1,62) = 4.848, p = 0.0314, Cohen’s d = 0.839, Fig. 6A). Maltreated dams exhibited higher levels of Bdnf expression relative to control vehicle-treated dams (p = 0.0579), but no difference was found between maltreated dams given zebularine relative to vehicle-treated control animals (p = 0.372). A significant difference was found between control vehicle and zebularine groups, with zebularine increasing expression levels in control animals (p = 0.0363).

Animals with a history of maltreatment exhibited marginally elevated levels of Bdnf exon IV expression relative to animals with a history of nurturing care in infancy. Treatment with zebularine normalized levels of Bdnf IV expression in maltreated dams, however, this same treatment increased levels of Bdnf IV expression in animals with a history of nurturing maternal care (A). Maltreated dams exhibited increased ERα expression regardless of drug treatment (B). n = 10–23/group; *Denotes p < 0.05, comparison is the vehicle and zebularine nurturing care groups; **Denotes p < 0.01, comparison is maltreatment versus controls; #Denotes p < 0.06, comparison is the maltreatment vehicle group versus the control vehicle group.

A significant effect of infant condition was found for ERα expression (F(1,62) = 8.2, p = 0.0057, Cohen’s d = 1.091, Fig. 6B), such that maltreated animals administered zebularine or vehicle showed elevated levels of ERα expression relative to control animals. No significant effects of drug treatment or a drug X infant condition interaction were detected (p’s > 0.05). Taken together with the methylation data, results are consistent with the notion that maltreatment and zebularine have gene-specific effects.

Discussion

We replicated our previous finding that dams with a history of maltreatment mistreat their own offspring2. Further, we found that daily administration of zebularine at a dose previously shown to rescue aberrant DNA methylation and gene expression2 and forced swim behavior63 normalized maternal behavior in maltreated dams. Interestingly, this drug disturbed maternal behavior in animals without of a history of maltreatment such that these animals displayed enhanced levels of adverse behaviors toward offspring. We likewise found that zebularine was able to normalize Bdnf exon IV levels of methylation and gene expression. Consistent with the behavioral data, zebularine administration disturbed levels of Bdnf gene expression in animals with a history of nurturing maternal care in infancy. These data suggest that the effects of zebularine are specific to caregiving history, as the drug elicited opposite effects in animals with a history of maltreatment relative to animals with no history of maltreatment.

While it may seem perplexing that zebularine had contrasting effects on dams dependent on their early-life history, our lab has previously identified a number of differences within the epigenome resulting from exposure to our maltreatment paradigm2,9,17,18,19,20,53. These differences are widespread; we have discovered maltreatment-induced changes in methylation in the PFC2,17,18, amygdala20, and hippocampus20. Thus, it seems plausible that the divergent effects of the drug could be a result of the existing epigenetic differences in animals with different caregiving histories. Presumably, zebularine normalized aberrant methylation in dams with a history of maltreatment, and this in turn normalized their maternal behavior. Indeed, we found methylation of the Bdnf gene to be disrupted in maltreated animals. On the other hand, zebularine presumably disrupted normative methylation patterns in dams without a history of maltreatment which, in turn, produced disruptions in their maternal behavior. Consistent with our results, several studies have previously found behavioral disruptions in non-stressed animals administered zebularine65,66,67,68. These results hint heavily at the causal nature of the relationship between the epigenome and behavioral phenotypes. Our data also argue that future work is warranted to discern the conditions under which zebularine has beneficial as opposed to harmful impacts on behavior.

There is a precedent in the literature for other epigenome-modifying drugs to alter maternal responsiveness in female rodents. In a maternal sensitization paradigm, female mice treated with a histone deacetylase inhibitor showed increased maternal responsiveness toward pups69,70. In this study, the expression of genes known to be involved in maternal behavior, including estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) was altered for 30 days following the sensitization paradigm70, suggesting that the facilitatory effects of this drug on maternal behavior can be long-lasting. Additionally, maternal behavior has been improved by administration of drugs whose main target is not the epigenome, such as those that alter reward circuitry. For example, increasing levels of dopamine pharmacologically was found to increase levels of licking and grooming toward offspring in dams that received low levels of licking and grooming as infants71. However, to the knowledge of the authors this is the first time that an epigenome-modifying drug has been utilized to rectify maltreatment-induced aberrations in maternal behavior in adult animals.

Experiencing different types of early-life stress elicits diverse biological and behavioral outcomes13,72,73,74. It is unknown if behavioral consequences resulting from other types of early-life stress, such as maternal separation or prenatal stress, could be rectified by altering DNA methylation by the same strategy employed here. Additionally, our study focused on a female-specific behavior, and as such it is unclear if this drug would likewise ameliorate behavioral consequences of maltreatment in male subjects. For example, male rats subjected to the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources demonstrate deficits in fear extinction that are not observed in females exposed to the model1. Sex differences exist throughout the epigenome75,76,77 and in levels of epigenetic regulators78,79, so it is possible that epigenome-modifying treatments would not be equally effective in male and female subjects. It should be noted however that previous work from our lab established an ability for zebularine administered at the same dose as this study to rescue maltreatment-induced DNA methylation and gene expression in the PFC of both female and male subjects, which would suggest that zebularine would likewise be efficacious for behavioral deficits elicited by maltreatment in males2. While we examined behavior at a time point when maltreatment-induced DNA methylation is known to be rescued by zebularine treatment (i.e. 24 hours after a week of daily infusions), looking at the ability for zebularine to change behavior over the course of the seven day infusion regimen would also be an interesting future direction.

Our data lend support to the hypothesis that the epigenetic consequences of stress are causally linked to the behavioral outcomes. Further, these data suggest a role of Bdnf in maternal behavior, as we found Bdnf methylation and gene expression data to match the behavioral data (i.e. zebularine disturbed Bdnf levels and behavior in normal animals while rescuing behavior and Bdnf levels in maltreated animals). Numerous studies have found links between early life stress and Bdnf methylation and expression2,9,20,80,81,82 and early life stress and altered maternal behavior2,56,57,58, but the direct relationship between maternal behavior and Bdnf has been largely unexplored. One study has provided evidence of correlations between Bdnf DNA methylation and neural activity associated with maternal response to child stimuli83. While psychiatric disorders such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder have been linked with low levels of Bdnf expression in certain brain regions such as the hippocampus84,85,86, elevated levels of Bdnf have likewise been linked with deleterious outcomes87,88,89. It is possible that aberrant levels of Bdnf expression in either direction (i.e. elevated or reduced as compared to normative levels) could induce adverse outcomes. We speculate that, because Bdnf is associated with plasticity, aberrant Bdnf levels could interfere with the plasticity that typically occurs in dams to drive maternal behavior. Consistent with this notion, our study found levels of ERα to be altered in maltreated dams, and ERα is one target of plasticity in the maternal brain32,90. Further study is necessary to elucidate the contribution of Bdnf to maternal behavior.

Because the MPOA is a heterogeneous nucleus with varied neuronal projections91,92, future work is needed to discern the precise neurobiological pattern of gene expression altered by maltreatment and zebularine treatment and the contribution of these sub-regions to maternal behavior in the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources. Though certain genes, including ERα, have been found to be altered as a result of early life experience in only select sub-regions of the MPOA93, our methods do not provide this level of detail. One seemingly counterintuitive finding from our study was the increased expression of ERα in MPOA of the maltreatment groups. This is in contrast to other reports that found increased ERα expression in the MPOA of animals that received nurturing care during early postnatal life7,90,93. Direct comparison between our study and others is difficult because of the different early-life paradigms and measures of maternal behavior employed, which could be responsible for the different outcomes10,52. Perhaps, elevated levels of ERα expression in the MPOA of maltreated dams serve a compensatory function, as ERα is a transcription factor that drives the expression of other genes94,95,96,97.

While we found Bdnf methylation to be normalized in the brain of maltreated dams administered zebularine, future work is needed to establish which other genes could be underlying the observed behavioral effects of zebularine. It is important to note that, similar to our data here, other reports show selective drug-induced changes in expression of genes involved in maternal behavior associated with enhanced maternal responsiveness70. For example, in the previously mentioned study that observed changes in ERβ expression after exposure to a histone deacetylase inhibitor, no changes in Oxtr expression were detected70. Such data support the idea that altering methylation and expression of select genes is sufficient to alter maternal responsiveness. However, the impact of epigenome-modifying drugs are time specific98,99,100. Since we have data from only one time point (i.e. 24 hours after the final of 7 daily infusions), it is unclear whether we would have seen a different pattern of gene expression and DNA methylation at other time points. Additional time points as well as addressing the circuit-level alterations responsible for the deficits seen in maternal behavior that zebularine is capable of modulating are important avenues for future research.

Zebularine cannot cross the blood-brain barrier and therefore needs to be administered centrally101. Further work is certainly warranted to determine whether less invasive treatments such as exercise, diet, and social enrichment, all measures that can easily be employed in humans, could have facilitatory effects on maternal behavior through altering the epigenome. The data reported here help to construct the necessary foundation for such efforts, as well as those showing that exercise102,103,104, diet105,106,107, and social interaction108,109,110 have lasting influences on the epigenome. Continued exploration of factors that can affect behavioral outcomes associated with early adversity holds promise of knowledge that can then be leveraged in the development of treatments and/or interventions for humans affected by early adversity. This is especially critical given that the impact of maltreatment on brain and behavior is multigenerational. One example of this comes from a recent study that found reduced cortical gray matter volume in the brains of offspring of women that experienced maltreatment in childhood111. It is thus important to establish treatments aimed at maternal behavior and the associated neurobiological deficits to not just improve outcomes for those directly exposed to adversity but the outcomes for following generations as well.

Overall, the finding that targeting the epigenome was successful in attenuating poor maternal behavior and aberrant DNA methylation and gene expression is an exciting step forward in the literature. These data confirm the utility of a rodent model to study the behavioral phenomenon of multigenerational patterns of parenting. They then further provide support for studying the relationship between maltreatment-induced epigenetic modifications and perpetuated patterns of maternal maltreatment of offspring. Finally, they offer insight into the potential of exploiting that relationship to subvert the often tragic outcomes of adversity.

Methods

Subjects

All animal procedures were conducted following approval by the University of Delaware Institutional Animal Care and Use committee using NIH established guidelines. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study utilized Long-Evans rats that were bred in house. Dams were maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle and were given ad libitum access to food and water. Postnatal day (PN) 0 was classified as the day of parturition. Figure 7 provides an approximate timeline of experimental procedures performed in this study.

This figure depicts an approximate timeline of experimental procedures that occurred to our experimental subjects. First, animals were exposed to the infant caregiver manipulations from PN1-7. Next, they were bred with naïve breeder males and allowed to give birth to their own litter. One day following parturition, stereotaxic surgery to implant a chronic cannula into the left lateral ventricle was conducted and subjects were allowed one day of recovery. After recovery, infusions of either zebularine or vehicle were administered daily for seven days. One day after the final infusion, a behavioral video was collected and brains were harvested from the subjects.

Caregiving manipulations

Rodent pups were exposed to the scarcity adversity model of low nesting resources for 30 minutes per day from PN 1–71,2,18,19,20,52,82. This model employs a within litter design whereby 1/3 of the litter is dedicated to the maltreatment condition, 1/3 of the litter is dedicated to the cross-foster care condition, and 1/3 of the litter receives normal maternal care. For the maltreatment condition, pups were exposed to another dam with limited nesting resources (~100 ml) in a novel environment. Dams were matched for postpartum age and diet to the biological dam of the experimental litter, as pups are unable to distinguish between their biological dam and a diet-matched dam112. In the cross-foster care condition, pups were also exposed to another dam in a novel environment. However, this dam had been given ample nesting resources (2–3 cm layer) and is familiar with the environment (i.e. had habituated for one hour). In the normal maternal care condition, each day the pups were marked with a nontoxic Sharpie® marker, weighed, and subsequently returned to the home cage with their biological mother. When possible, equal numbers of male and female pups were placed into each caregiver condition. However, at least one male and one female pup were placed into each of the 3 experimental groups. Caregiving behavior in each of these conditions was recorded. A subset of 5 of the 13 litters from which experimental subjects were taken was scored to confirm the replicability of this model (i.e. increased levels of adverse behavior by the caregiver during the maltreatment condition relative to the two control conditions). Videos were coded for adverse (roughly handling, dropping, dragging, stepping on, or actively avoiding pups) behaviors in five-minute time bins. The resulting scores for each caregiving behavior were then averaged across the seven sessions for statistical analysis (thus data shown in Fig. 1 are comprised of caregiving behavior from PN 1–7).

At the time of weaning, male and female offspring were separated and only female offspring were utilized for the duration of the study. Males were used for other experiments in our laboratory. Female subjects were placed into cages of two or three animals from the same infant condition. When female rodents exposed to these infant manipulations reached adulthood (around PN55), they were be bred with naïve breeder males and permitted to give birth. After the female had successfully bred with the male (i.e. a sperm plug was found), animals were single-housed and remained undisturbed until one day following parturition. To examine the presence of the Trivers–Willard effect pups were sexed and counted64.

Stereotaxic surgery and drug infusions

One day after parturition, stereotaxic surgery was performed to implant a cannula into the left lateral ventricle following a protocol similar to one used previously by our lab2. To induce anesthesia, dams were placed in an induction chamber containing 5% isoflurane in oxygen. Once anesthesia was induced, animals were administered 2 mL of sterile saline and 0.03 mg/kg buprenorphine. The dam was then placed into a stereotaxic frame. Anesthesia was maintained using 2–3% isoflurane in oxygen and a stainless steel guide cannula (22 gauge, 8 mm length, Plastics One Inc., Roanoke, VA) was implanted into the left lateral ventricle (1.5 mm posterior, 2.0 mm lateral, and 3.0 mm ventral relative to bregma). At the time of surgery, cannula placement was verified using gravitational saline letdown as has been done in previous reports113. A dummy cannula extending 1 mm beyond the guide cannula was inserted into the guide cannula upon cessation of surgery to prevent cannula blockage. While the dam was undergoing surgery, her pups were left in the home cage on a heating pad and monitored. Dams were allowed one day of recovery after surgery during which they were left undisturbed and monitored to ensure appropriate recovery (e.g. maintaining weight and grooming properly).

Following recovery, daily infusions of zebularine or vehicle were performed. Zebularine is a cytidine analog known to incorporate into DNA and consequently alters DNA methylation114. This drug is known to alter levels of DNA methylation when administered to adult rats2,65,66,68. We selected a drug dose and treatment regimen shown to reverse aberrant DNA methylation and gene expression levels2 as well as reverse maltreatment-induced aberrations in forced swim behavior63. Specifically, zebularine (600 ng/μl in 10% DMSO, 2 μl volume, infusion rate of 1 μl/min) was administered once daily for seven days. Vehicle was comprised of 10% DMSO in sterile saline. Each experimental group contained between 10–12 subjects.

Adult behavior

A 30 minute behavioral recording was collected 24 hours following the final infusion, as this is the same time point we have observed an effect of zebularine on methylation and gene expression2. Recordings were later coded offline for adverse (roughly handling, dropping, dragging, stepping on, and avoiding the pups) maternal behaviors by scorers blind to experimental conditions. Because a previous report from our lab found enhanced levels of adverse behaviors performed toward offspring in dams with a history of maltreatment2, the total number of adverse behaviors conducted throughout the 30 minute recording were tallied. This method of recording each bout of a behavior has been used by others to probe for differences in maternal care in dams with a history of early-life stress115, providing more resolution that can be lost when collapsing behaviors across time bins (as we have commonly done).

DNA methylation

Immediately after the behavioral recording was collected 24 hours following the final infusion, dams were sacrificed and brains were harvested. Brains were flash-frozen in isopentane and stored at −80 °C until later processing. Brains were sliced at 250 μm in a cryostat at −12 °C. Cannula placement in the left lateral ventricle was visually confirmed during brain slicing. Tissue was dissected from the MPOA over dry ice using stereotaxic coordinates obtained from a brain atlas (AP + 0.12 mm through −0.75 mm relative to bregma)116. DNA and RNA were extracted from the MPOA using the Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit. To analyze nucleic acid quality and concentration, spectrophotometry was conducted (NanoDrop 2000). DNA was subsequently bisulfite treated (Epitect Bisulfite Kit, Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). Following bisulfite treatment, DNA was then processed using direct bisulfite sequencing PCR following an established lab protocol to examine Bdnf methylation at exon IV2,20,80. Samples were sent to the University of Delaware Sequencing and Genotyping Center for sequencing using reverse primers. For each CG site (i.e. 1–11 of Bdnf exon IV), percent methylation was calculated using the ratio between peak values of G and A (G/[G + A]) on chromatograms using Chromas software.

The same DNA used for locus-specific analyses was used to assess global methylation. MethylFlash™ Methylated DNA Quantification Kits were used to quantify levels of genome-wide methylation (5-mC) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Epigentek, Brooklyn, NY). Absorbance was measured using the Infinite ® F50 microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) with the amount of 5-mC DNA proportional to the intensity of the optical density. Samples were run in vertical duplicates at a strict concentration of 100 ng/well with total volume added per well not ranging outside of 2–5 ul per well.

Gene expression

Gene expression was examined for a subset of genes using a previously established protocol2,53. The genes selected due to their role in processing rewarding stimuli, including the rewarding properties of pup interactions, included dopamine receptor 1 (Drd1) and µ-opioid receptor 1 (Oprm1)37,47,50,71,117. Genes selected due to their role in the stress response included corticotropin releasing factor receptor type 1 (Crfr1) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR)5,118,119,120,121,122. The plasticity-related genes selected were Bdnf (exons I, IV, and IX) and fos123,124. Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and oxytocin receptor (Oxtr) genes were assayed due to their role in maternal behavior onset29,47,49,125. The DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) DNMT1 and DNMT3a were probed to establish levels of epigenetic regulators. RNA taken from the brains of dams was subjected to a reverse-transcription reaction using a cDNA synthesis kit (Qiagen QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit). Subsequently, real-time PCR (Bio-Rad CFX96) was conducted using Taqman probes on cDNA (Applied Biosystems). PCR reactions were run in duplicates, and the results were averaged. Tubulin expression was used as a reference gene. Confirming stability of tubulin across our conditions, we did not find an effect of infant condition (F(1,64) = 1.135, p = 0.2908), drug treatment (F(1,64) = 0.04825, p = 0.8268), nor an interaction effect (F(1,64) = 0.247, p = 0.6209). Gene expression was calculated for target genes relative to tubulin using the 2−ΔΔCT method126.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism. Behavioral data collected from the infant manipulations were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. Behavioral (i.e. total number of adverse maternal behaviors in the 30 minute recording), DNA methylation, and gene expression data from dams previously exposed to infant manipulations were analyzed using two-way ANOVAs. T-tests were used for post-hoc analyses to further probe statistically significant effects, with Bonferroni corrections applied when necessary to reduce the chance of type I errors127. For all analyses, p < 0.05 was used as a threshold for statistical significance. Marginal significance was set at p < 0.06.

References

Doherty, T. S., Blaze, J., Keller, S. M. & Roth, T. L. Phenotypic outcomes in adolescence and adulthood in the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources outside the home cage. Developmental Psychobiology 59, 703–714 (2017).

Roth, T. L., Lubin, F. D., Funk, A. J. & Sweatt, J. D. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biological Psychiatry 65, 760–769 (2009).

Champagne, F. A., Francis, D. D., Mar, A. & Meaney, M. J. Variations in maternal care in the rat as a mediating influence for the effects of environment on development. Physiology & Behavior 79, 359–371 (2003).

Meaney, M. J. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annual Review of Neuroscience 24, 1161–1192 (2001).

Weaver, I. C. et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature Neuroscience 7, 847–854 (2004).

Champagne, F. A. & Curley, J. P. Epigenetic mechanisms mediating the long-term effects of maternal care on development. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 33, 593–600 (2009).

Champagne, F. A. et al. Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-alpha1b promoter and estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinology 147, 2909–2915 (2006).

Anier, K. et al. Maternal separation is associated with DNA methylation and behavioural changes in adult rats. European Neuropsychopharmacology 24, 459–468 (2014).

Blaze, J., Asok, A. & Roth, T. L. Long-term effects of early-life caregiving experiences on brain-derived neurotrophic factor histone acetylation in the adult rat mPFC. Stress 18, 607–615 (2015).

Keller, S. M. & Roth, T. L. Environmental influences on the female epigenome and behavior. Environmental Epigenetics 2, 1–10 (2016).

Roth, T. L. & Sweatt, J. D. Epigenetic marking of the BDNF gene by early-life adverse experiences. Hormones and Behavior 59, 315–320 (2011).

McGowan, P. O. & Roth, T. L. Epigenetic pathways through which experiences become linked with biology. Development and Psychopathology 27, 637–648 (2015).

St-Cyr, S. & McGowan, P. O. Programming of stress-related behavior and epigenetic neural gene regulation in mice offspring through maternal exposure to predator odor. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 9, 145 (2015).

Murgatroyd, C. A. et al. Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress. Nature Neuroscience 12, 1559–1566 (2009).

Maccari, S., Krugers, H., Morley Fletcher, S., Szyf, M. & Brunton, P. The consequences of early life adversity: Neurobiological, behavioural and epigenetic adaptations. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 26, 707–723 (2014).

Lutz, P.-E. & Turecki, G. DNA methylation and childhood maltreatment: from animal models to human studies. Neuroscience 264, 142–156 (2014).

Blaze, J. & Roth, T. L. Caregiver maltreatment causes altered neuronal DNA methylation in female rodents. Development and Psychopathology 29, 477–489 (2017).

Blaze, J., Scheuing, L. & Roth, T. L. Differential methylation of genes in the medial prefrontal cortex of developing and adult rats following exposure to maltreatment or nurturing care during infancy. Developmental Neuroscience 35, 306–316 (2013).

Doherty, T. S., Forster, A. & Roth, T. L. Global and gene-specific DNA methylation alterations in the adolescent amygdala and hippocampus in an animal model of caregiver maltreatment. Behavioural Brain Research (2016).

Roth, T. L., Matt, S., Chen, K., Blaze, J. & Bdnf, D. N. A. methylation modifications in the hippocampus and amygdala of male and female rats exposed to different caregiving environments outside the homecage. Developmental Psychobiology 56, 1755–1763 (2014).

McGowan, P. O. et al. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nature Neuroscience 12, 342–348 (2009).

Labonté, B. et al. Genome-wide epigenetic regulation by early-life trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry 69, 722–731 (2012).

Perroud, N. et al. Increased methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment: a link with the severity and type of trauma. Translational Psychiatry 1, e59 (2011).

Jones, P. A. & Takai, D. The role of DNA methylation in mammalian epigenetics. Science 293, 1068–1070 (2001).

Holliday, R. & Grigg, G. DNA methylation and mutation. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 285, 61–67 (1993).

Razin, A. & Riggs, A. D. DNA methylation and gene function. Science 210, 604–610 (1980).

Li, M. & Fleming, A. S. Differential involvement of nucleus accumbens shell and core subregions in maternal memory in postpartum female rats. Behavioral Neuroscience 117, 426 (2003).

Li, M. & Fleming, A. S. The nucleus accumbens shell is critical for normal expression of pup-retrieval in postpartum female rats. Behavioural Brain Research 145, 99–111 (2003).

Olazabal, D. & Young, L. Oxytocin receptors in the nucleus accumbens facilitate “spontaneous” maternal behavior in adult female prairie voles. Neuroscience 141, 559–568 (2006).

Numan, M. & Numan, M. J. Projection sites of medial preoptic area and ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis neurons that express Fos during maternal behavior in female rats. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 9, 369–384 (1997).

Numan, M. & Numan, M. A lesion and neuroanatomical tract tracing analysis of the role of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in retrieval behavior and other aspects of maternal responsiveness in rats. Developmental Psychobiology 29, 23–51 (1996).

Lonstein, J. & De Vries, G. Maternal behaviour in lactating rats stimulates c-fos in glutamate decarboxylase-synthesizing neurons of the medial preoptic area, ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and ventrocaudal periaqueductal gray. Neuroscience 100, 557–568 (2000).

Perrin, G., Meurisse, M. & Lévy, F. Inactivation of the medial preoptic area or the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis differentially disrupts maternal behaviour in sheep. Hormones and Behavior 52, 461–473 (2007).

Numan, M. & Numan, M. J. Importance of pup-related sensory inputs and maternal performance for the expression of Fos-like immunoreactivity in the preoptic area and ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of postpartum rats. Behavioral Neuroscience 109, 135 (1995).

Numan, M., Numan, M. J., Marzella, S. R. & Palumbo, A. Expression of c-fos, fos B, and egr-1 in the medial preoptic area and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis during maternal behavior in rats. Brain Research 792, 348–352 (1998).

Pedersen, C. A., Caldwell, J. D., Walker, C., Ayers, G. & Mason, G. A. Oxytocin activates the postpartum onset of rat maternal behavior in the ventral tegmental and medial preoptic areas. Behavioral Neuroscience 108, 1163 (1994).

Hansen, S., Harthon, C., Wallin, E., Löfberg, L. & Svensson, K. Mesotelencephalic dopamine system and reproductive behavior in the female rat: effects of ventral tegmental 6-hydroxydopamine lesions on maternal and sexual responsiveness. Behavioral Neuroscience 105, 588 (1991).

Hernandez-Gonzalez, M., Navarro-Meza, M., Prieto-Beracoechea, C. & Guevara, M. Electrical activity of prefrontal cortex and ventral tegmental area during rat maternal behavior. Behavioural Processes 70, 132–143 (2005).

Afonso, V. M., Sison, M., Lovic, V. & Fleming, A. S. Medial prefrontal cortex lesions in the female rat affect sexual and maternal behavior and their sequential organization. Behavioral Neuroscience 121, 515–526 (2007).

Sabihi, S., Dong, S. M., Durosko, N. E. & Leuner, B. Oxytocin in the medial prefrontal cortex regulates maternal care, maternal aggression and anxiety during the postpartum period. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 8, 258 (2014).

Ferris, C. F. et al. Oxytocin in the amygdala facilitates maternal aggression. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 652, 456–457 (1992).

Fleming, A. S., Vaccarino, F. & Luebke, C. Amygdaloid inhibition of maternal behavior in the nulliparous female rat. Physiology & Behavior 25, 731–743 (1980).

Lubin, D. A., Elliott, J. C., Black, M. C. & Johns, J. M. An oxytocin antagonist infused into the central nucleus of the amygdala increases maternal aggressive behavior. Behavioral Neuroscience 117, 195–201 (2003).

Numan, M., Numan, M. J. & English, J. B. Excitotoxic amino acid injections into the medial amygdala facilitate maternal behavior in virgin female rats. Hormones and Behavior 27, 56–81 (1993).

Sheehan, T., Paul, M., Amaral, E., Numan, M. J. & Numan, M. Evidence that the medial amygdala projects to the anterior/ventromedial hypothalamic nuclei to inhibit maternal behavior in rats. Neuroscience 106, 341–356 (2001).

Numan, M. & Woodside, B. Maternity: neural mechanisms, motivational processes, and physiological adaptations. Behavioral Neuroscience 124, 715 (2010).

Numan, M. & Stolzenberg, D. S. Medial preoptic area interactions with dopamine neural systems in the control of the onset and maintenance of maternal behavior in rats. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 30, 46–64 (2009).

Numan, M., Rosenblatt, J. S. & Komisaruk, B. R. Medial preoptic area and onset of maternal behavior in the rat. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 91, 146 (1977).

Numan, M. Maternal behavior: neural circuits, stimulus valence, and motivational processes. Parenting 12, 105–114 (2012).

Afonso, V. M., King, S., Chatterjee, D. & Fleming, A. S. Hormones that increase maternal responsiveness affect accumbal dopaminergic responses to pupand food-stimuli in the female rat. Hormones and Behavior 56, 11–23 (2009).

Stolzenberg, D. S. & Champagne, F. A. Hormonal and non-hormonal bases of maternal behavior: the role of experience and epigenetic mechanisms. Hormones and Behavior 77, 204–210 (2016).

Walker, C.-D. et al. Chronic early life stress induced by limited bedding and nesting (LBN) material in rodents: critical considerations of methodology, outcomes and translational potential. Stress 20, 421–448 (2017).

Blaze, J. & Roth, T. L. Exposure to caregiver maltreatment alters expression levels of epigenetic regulators in the medial prefrontal cortex. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 31, 804–810 (2013).

Muzik, M. et al. Mother–infant bonding impairment across the first 6 months postpartum: The primacy of psychopathology in women with childhood abuse and neglect histories. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 16, 29–38 (2013).

Banyard, V. L. The impact of childhood sexual abuse and family functioning on four dimensions of women’s later parenting. Child Abuse & Neglect 21, 1095–1107 (1997).

Roberts, R., O’Connor, T., Dunn, J., Golding, J. & Team, A. S. The effects of child sexual abuse in later family life; mental health, parenting and adjustment of offspring. Child Abuse & Neglect 28, 525–545 (2004).

Bailey, H. N., DeOliveira, C. A., Wolfe, V. V., Evans, E. M. & Hartwick, C. The impact of childhood maltreatment history on parenting: A comparison of maltreatment types and assessment methods. Child Abuse & Neglect 36, 236–246 (2012).

Cort, N. A., Toth, S. L., Cerulli, C. & Rogosch, F. Maternal intergenerational transmission of childhood multitype maltreatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 20, 20–39 (2011).

Cross, D. et al. Maternal child sexual abuse Is associated with lower maternal warmth toward daughters but not sons. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 25, 813–826 (2016).

Champagne, F. A. Epigenetic mechanisms and the transgenerational effects of maternal care. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 29, 386–397 (2008).

Francis, D. D., Champagne, F. A. & Meaney, M. J. Variations in maternal behaviour are associated with differences in oxytocin receptor levels in the rat. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 12, 1145–1148 (2000).

Francis, D. D., Diorio, J., Liu, D. & Meaney, M. J. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science 286, 1155–1158 (1999).

Keller, S. M., Doherty, T. S. & Roth, T. L. Pharmacological manipulation of DNA methylation in adult female rats normalizes behavioral consequences of early-life maltreatment. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 12, 126 (2018).

Trivers, R. L. & Willard, D. E. Natural selection of parental ability to vary the sex ratio of offspring. Science 179, 90–92 (1973).

Roth, E. D. et al. DNA methylation regulates neurophysiological spatial representation in memory formation. Neuroepigenetics 2, 1–8 (2015).

Lubin, F. D., Roth, T. L. & Sweatt, J. D. Epigenetic regulation of BDNF gene transcription in the consolidation of fear memory. Journal of Neuroscience 28, 10576–10586 (2008).

Anier, K., Malinovskaja, K., Aonurm-Helm, A., Zharkovsky, A. & Kalda, A. DNA methylation regulates cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 2450–2461 (2010).

Matt, S. M. et al. Inhibition of DNA methylation with zebularine alters lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behavior and neuroinflammation in mice. Frontiers in Neuroscience 12, 636 (2018).

Stolzenberg, D. S., Stevens, J. S. & Rissman, E. F. Experience-facilitated improvements in pup retrieval; evidence for an epigenetic effect. Hormones and Behavior 62, 128–135 (2012).

Stolzenberg, D. S., Stevens, J. S. & Rissman, E. F. Histone deacetylase inhibition induces long-lasting changes in maternal behavior and gene expression in female mice. Endocrinology 155, 3674–3683 (2014).

Champagne, F. A. et al. Variations in nucleus accumbens dopamine associated with individual differences in maternal behavior in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience 24, 4113–4123 (2004).

Dong, E. et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor epigenetic modifications associated with schizophrenia-like phenotype induced by prenatal stress in mice. Biological Psychiatry 77, 589–596 (2015).

Mychasiuk, R., Ilnytskyy, S., Kovalchuk, O., Kolb, B. & Gibb, R. Intensity matters: brain, behaviour and the epigenome of prenatally stressed rats. Neuroscience 180, 105–110 (2011).

Schmidt, M. V., Wang, X.-D. & Meijer, O. C. Early life stress paradigms in rodents: potential animal models of depression? Psychopharmacology 214, 131–140 (2011).

McCarthy, M. M. et al. The epigenetics of sex differences in the brain. Journal of Neuroscience 29, 12815–12823 (2009).

Nugent, B. M. et al. Brain feminization requires active repression of masculinization via DNA methylation. Nature Neuroscience 18, 690–697 (2015).

Schwarz, J. M., Nugent, B. M. & McCarthy, M. M. Developmental and hormone-induced epigenetic changes to estrogen and progesterone receptor genes in brain are dynamic across the life span. Endocrinology 151, 4871–4881 (2010).

Kolodkin, M. & Auger, A. Sex difference in the expression of DNA methyltransferase 3a in the rat amygdala during development. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 23, 577–583 (2011).

Kurian, J. R., Forbes-Lorman, R. M. & Auger, A. P. Sex difference in mecp2 expression during a critical period of rat brain development. Epigenetics 2, 173–178 (2007).

Blaze, J. et al. Intrauterine exposure to maternal stress alters Bdnf IV DNA methylation and telomere length in the brain of adult rat offspring. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 62, 56–62 (2017).

Seo, M. K. et al. Early life stress increases stress vulnerability through BDNF gene epigenetic changes in the rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 105, 388–397 (2016).

Hill, K. T., Warren, M. & Roth, T. L. The influence of infant-caregiver experiences on amygdala Bdnf, OXTr, and NPY expression in developing and adult male and female rats. Behavioural Brain Research 272, 175–180 (2014).

Moser, D. A. et al. BDNF methylation and maternal brain activity in a violence-related sample. Plos One 10, e0143427, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143427 (2015).

Roth, T. L., Zoladz, P. R., Sweatt, J. D. & Diamond, D. M. Epigenetic modification of hippocampal Bdnf DNA in adult rats in an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 45, 919–926 (2011).

Yu, H. & Chen, Z.-Y. The role of BDNF in depression on the basis of its location in the neural circuitry. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 32, 3 (2011).

Bai, M. et al. Abnormal hippocampal BDNF and miR-16 expression is associated with depression-like behaviors induced by stress during early life. PloS One 7, e46921 (2012).

Meredith, G. E., Callen, S. & Scheuer, D. A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression is increased in the rat amygdala, piriform cortex and hypothalamus following repeated amphetamine administration. Brain Research 949, 218–227 (2002).

Takei, S. et al. Enhanced hippocampal BDNF/TrkB signaling in response to fear conditioning in an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 45, 460–468 (2011).

Berton, O. et al. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science 311, 864–868 (2006).

Champagne, F. A. & Curley, J. P. Maternal regulation of estrogen receptor α methylation. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 8, 735–739 (2008).

Kohl, J. et al. Functional circuit architecture underlying parental behaviour. Nature 556, 326 (2018).

Wu, Z., Autry, A. E., Bergan, J. F., Watabe-Uchida, M. & Dulac, C. G. Galanin neurons in the medial preoptic area govern parental behaviour. Nature 509, 325 (2014).

Peña, C. J., Neugut, Y. D. & Champagne, F. A. Developmental timing of the effects of maternal care on gene expression and epigenetic regulation of hormone receptor levels in female rats. Endocrinology 154, 4340–4351 (2013).

Young, L. J., Wang, Z., Donaldson, R. & Rissman, E. F. Estrogen receptor α is essential for induction of oxytocin receptor by estrogen. Neuroreport 9, 933–936 (1998).

Bale, T., Pedersen, C. & Dorsa, D. CNS oxytocin receptor mRNA expression and regulation by gonadal steroids. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 395, 269–280 (1995).

Pedersen, C. A., Ascher, J. A., Monroe, Y. L. & Prange, A. J. Oxytocin induces maternal behavior in virgin female rats. Science 216, 648–650 (1982).

Pedersen, C. A. & Prange, A. J. Induction of maternal behavior in virgin rats after intracerebroventricular administration of oxytocin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 76, 6661–6665 (1979).

Elvir, L., Duclot, F., Wang, Z. & Kabbaj, M. Epigenetic regulation of motivated behaviors by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews (2017).

Billam, M., Sobolewski, M. D. & Davidson, N. E. Effects of a novel DNA methyltransferase inhibitor zebularine on human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 120, 581–592 (2010).

Zhou, P., Lu, Y. & Sun, X.-H. Effects of a novel DNA methyltransferase inhibitor Zebularine on human lens epithelial cells. Molecular Vision 18, 22 (2012).

Beumer, J. H. et al. A mass balance and disposition study of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor zebularine (NSC 309132) and three of its metabolites in mice. Clinical Cancer Research 12, 5826–5833 (2006).

Denham, J., Marques, F. Z., O’Brien, B. J. & Charchar, F. J. Exercise: putting action into our epigenome. Sports Medicine 44, 189–209 (2014).

Boschen, K., McKeown, S., Roth, T. & Klintsova, A. Impact of exercise and a complex environment on hippocampal dendritic morphology, Bdnf gene expression, and DNA methylation in male rat pups neonatally exposed to alcohol. Developmental Neurobiology 77, 708–725 (2017).

Laker, R. C. et al. Exercise prevents maternal high-fat diet–induced hypermethylation of the Pgc-1α gene and age-dependent metabolic dysfunction in the offspring. Diabetes 63, 1605–1611 (2014).

Moreno Gudiño, H., Carías Picón, D. & de Brugada Sauras, I. Dietary choline during periadolescence attenuates cognitive damage caused by neonatal maternal separation in male rats. Nutritional Neuroscience 20, 327–335 (2017).

Lillycrop, K. A., Phillips, E. S., Jackson, A. A., Hanson, M. A. & Burdge, G. C. Dietary protein restriction of pregnant rats induces and folic acid supplementation prevents epigenetic modification of hepatic gene expression in the offspring. Journal of Nutrition 135, 1382–1386 (2005).

Carlin, J., George, R. & Reyes, T. M. Methyl donor supplementation blocks the adverse effects of maternal high fat diet on offspring physiology. Plos One 8, e63549 (2013).

Champagne, F. A. & Curley, J. P. How social experiences influence the brain. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 15, 704–709 (2005).

Branchi, I., Karpova, N. N., D’Andrea, I., Castrén, E. & Alleva, E. Epigenetic modifications induced by early enrichment are associated with changes in timing of induction of BDNF expression. Neuroscience Letters 495, 168–172 (2011).

Kuzumaki, N. et al. Hippocampal epigenetic modification at the brain‐derived neurotrophic factor gene induced by an enriched environment. Hippocampus 21, 127–132 (2011).

Moog, N. K. et al. Intergenerational effect of maternal exposure to childhood maltreatment on newborn brain anatomy. Biological Psychiatry 83, 120–127 (2018).

Leon, M. Dietary control of maternal pheromone in the lactating rat. Physiology & Behavior 14, 311–319 (1975).

Asok, A., Schulkin, J. & Rosen, J. B. Corticotropin releasing factor type-1 receptor antagonism in the dorsolateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis disrupts contextually conditioned fear, but not unconditioned fear to a predator odor. Psychoneuroendocrinology 70, 17–24 (2016).

Champion, C. et al. Mechanistic insights on the inhibition of c5 DNA methyltransferases by zebularine. PLoS One 5, e12388 (2010).

Murgatroyd, C. A. & Nephew, B. C. Effects of early life social stress on maternal behavior and neuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 219–228 (2013).

Paxinos, G. & Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates in Stereotaxic Coordinates. (Elsevier, 2007).

Nelson, E. E. & Panksepp, J. Brain substrates of infant-mother attachment: contributions of opioids, oxytocin, and norepinephrine. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 22, 437–452 (1998).

Müller, M. B. et al. Limbic corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 mediates anxiety-related behavior and hormonal adaptation to stress. Nature Neuroscience 6, 1100–1107 (2003).

Zaidan, H., Leshem, M. & Gaisler-Salomon, I. Prereproductive stress to female rats alters corticotropin releasing factor type 1 expression in ova and behavior and brain corticotropin releasing factor type 1 expression in offspring. Biological Psychiatry 74, 680–687 (2013).

Murgatroyd, C. A., Peña, C. J., Podda, G., Nestler, E. J. & Nephew, B. C. Early life social stress induced changes in depression and anxiety associated neural pathways which are correlated with impaired maternal care. Neuropeptides 52, 103–111 (2015).

Gammie, S. C., Bethea, E. D. & Stevenson, S. A. Altered maternal profiles in corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 deficient mice. BMC Neuroscience 8, 17 (2007).

Chourbaji, S. et al. Differences in mouse maternal care behavior–Is there a genetic impact of the glucocorticoid receptor? PLoS One 6, e19218 (2011).

Gandolfi, D. et al. Activation of the CREB/c-fos pathway during long-term synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum granular layer. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 11, 184 (2017).

Lu, B., Nagappan, G. & Lu, Y. In Neurotrophic factors 223–250 (Springer, 2014).

Fahrbach, S. E., Morrell, J. I. & Pfaff, D. W. Possible role for endogenous oxytocin in estrogen-facilitated maternal behavior in rats. Neuroendocrinology 40, 526–532 (1985).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Sedgwick, P. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni correction. BMJ 344, e509 (2012).

Acknowledgements

For assistance with experiments, we would like to thank Isabella Archer, Shannon Trombley, Anna Nowak, Ashley Atalese, Johanna Chajes, Richard Keller, Nabil Nasir, Derica Nyameke, and Lauren Reich. Funding for this work was provided by a University Doctoral Fellowship awarded to SMK, a University Dissertation Fellowship awarded to TSD, and The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD087509) awarded to TLR. We thank the Delaware Biotechnology Institute for the use of their core facilities (supported by the Delaware INBRE program, with a grant from NIGMS [P20 GM103446] and the state of Delaware).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.K. and T.L.R. designed the study. S.M.K. and T.S.D. collected the data, and all authors took part in interpretation of the results. S.M.K. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and T.S.D. and T.L.R. edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keller, S.M., Doherty, T.S. & Roth, T.L. Pharmacological manipulation of DNA methylation normalizes maternal behavior, DNA methylation, and gene expression in dams with a history of maltreatment. Sci Rep 9, 10253 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46539-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46539-4

This article is cited by

-

Epigenetic Consequences of Adversity and Intervention Throughout the Lifespan: Implications for Public Policy and Healthcare

Adversity and Resilience Science (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.