Abstract

This study was aimed to compare serial long-term postoperative changes in quality-of-life (QoL) between photoselective-vaporization (PVP) using 120W-High-Performance-System and holmium-laser-enucleation (HoLEP) in benign-prostatic-hyperplasia (BPH) patients and to identify factors influencing the QoL improvement at the short-term, mid-term and long-term follow-up visits after surgery. We analyzed 1,193 patients with a baseline QoL-index ≥2 who underwent PVP (n = 439) or HoLEP (n = 754). Surgical outcomes were serially compared between the two groups at up to 60-months using the International-Prostatic-Symptom-Score (I-PSS), uroflowmetry, and serum PSA. We used logistic regression analysis to identify predictors of QoL improvement (a reduction in the QoL-index ≥50% compared with baseline) at the short-term (12-months), mid-term (36-months), and long term (60-months) follow-up after surgery. In both groups, the QoL-index was decreased throughout the entire follow-up period compared with that at baseline. There were no significant differences in postoperative changes from the baseline QoL-index between the two groups during the 48-month follow-up, except at 60-months. The degree of improvement in QoL at 60-months after HoLEP was greater than that after PVP. A lower baseline storage-symptom-subscore and a higher bladder-outlet-obstruction-index (BOOI) were independent factors influencing QoL improvement at the short-term. No independent factor influences QoL improvement at the mid- or long-term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is known to be a highly prevalent disease with increasing age1,2,3, and it is directly and negatively related to the quality of life (QoL)2,4. As expectations for QoL are increasing with increased life expectancy, many elderly men with LUTS become less tolerant5 and complain about LUTS, leading to poor QoL, although LUTS due to BPH is not life threatening. Thus, one of the aims of treatment for BPH patients is improving QoL through improving LUTS6, and, to improve LUTS and QoL in men with severe LUTS, surgical treatment would be useful5.

For decades, standard treatment for BPH was transurethral prostatectomy (TURP)3,7,8. Recently, as alternatives for TURP, laser surgeries such as photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP) and holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) have been increasingly performed9, because of fewer perioperative complications, which are related to perioperative QoL10. Specifically, in several studies, PVP and HoLEP were reported to have, at least, noninferior efficacy, less bleeding, and less catheter duration than TURP11. Thus, PVP was recommended in patients with a high cardiovascular risk and high bleeding risk12; additionally, HoLEP has an advantage regarding hemostasis13. As less complications would be expected to lead to better QoL as mentioned above10, PVP and HoLEP could be the good option to LUTS patient who pursuit QoL.

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have directly compared postoperative treatment outcomes between PVP and HoLEP, focusing on improvement in QoL during a serial long-term follow-up period, although a few short-term follow-up studies showed no significant differences in the postoperative improvement of QoL during a one-year follow-up after surgery14,15. Additionally, few studies have investigated which factors could influence postoperative improvements in QoL after the two laser surgeries. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare serial long-term postoperative changes in QoL between PVP using a 120-W GreenLight high-performance system (HPS) and HoLEP in patients with BPH and to determine the factors influencing the improvement of QoL at the short-term, mid-term, and long-term follow-up visits after surgery using a serial long-term follow-up database.

Results

Baseline characteristics

In comparing the baseline characteristics between the PVP and HoLEP groups, the PVP group had a higher level of serum PSA, a smaller prostate volume, a higher voiding symptom score (VSS), a higher storage symptom score (SSS), a higher total International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS), a longer operation time, and greater energy applied during the surgeries than the HoLEP group (Table 1). However, the baseline QoL index was not different between the groups.

Regarding the baseline urodynamic data, the HoLEP group showed a smaller postvoid residual urine volume (PVR), a smaller maximum cystometric capacity (MCC), a higher bladder outlet obstruction index (BOOI), a higher bladder contractility index (BCI), and a higher percentage of patients with involuntary detrusor contraction (IDC) than the PVP group (Table 1).

Serial postoperative outcomes after PVP or HoLEP

In both the PVP and HoLEP groups, the value of the QoL index at each follow-up visit was significantly decreased during the entire follow-up period after surgery compared with that at the baseline (Fig. 1). Additionally, according to the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) test to adjust for the effect of time on the QoL outcomes, no significant differences were found in the change of the QoL index over time between the PVP and HoLEP groups during the 60-month follow-up period (Supplementary Fig. S2). The improvement in all outcomes parameters, including total I-PSS, VSS, SSS, the maximum flow rate (Qmax), PVR, and bladder voiding efficiency (BVE), was maintained during the entire follow-up period after PVP or HoLEP, except for Qmax at 60 months after PVP. However, the values of VSS and SSS starting from 36 months after the PVP were increased compared with those at 12 months after surgery, although their decrease was sustained up to 60 months after surgery compared with that at baseline. Meanwhile, the values of VSS starting from 24 months after the HoLEP were increased compared with those at 12 months after surgery, whereas those of SSS at 24, 36, 48 and 60 months after surgery were not different from 12 months postoperatively. The Qmax values in both the PVP and HoLEP groups were deteriorated starting from 24 months compared with those at 12 months after surgery. However, the increase in the Qmax value at all follow visits after the HoLEP was maintained up to 60 months compared with that at baseline, whereas the Qmax value at 60 months after the PVP was decreased to the baseline level. The incidence of transient urinary incontinence after HoLEP was higher than that after PVP (Table 2). Repeated BPH surgeries because of the regrowth of prostatic adenoma were performed for 12 patients in the PVP group but for none in the HoLEP group.

Serial postoperative outcomes after PVP and HoLEP. The asterisk (*) indicates that, at each follow-up visit, significant differences were found from the value at baseline. A dagger (†) and double dagger (‡) indicate that, at each follow-up visit, a significant difference was found from the baseline value at 1 year and 3 years of follow up, respectively (Paired t-test, p < 0.05).

Comparison of the postoperative changes in outcome parameters between PVP and HoLEP to that at the baseline

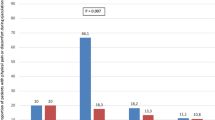

In terms of postoperative changes from the baseline in the QoL index, no significant differences were found between the groups during the 48-month follow-up period after surgery. However, the degree of reduction in the QoL index at 60 months after HoLEP was greater than that after PVP (Fig. 2). The percentages of patients with QoL improvement were 54.0%, 52.2%, and 43.1% at 1-, 3- and 5-years after PVP, and 57.7%, 53.7%, and 55.3% at 1-, 3- and 5-years after HoLEP, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

The degree of reduction in the total I-PSS and VSS during the entire follow-up period after HoLEP was greater than that after PVP, except for that at one month and 24 months after the surgeries (Fig. 2). Additionally, the degree of increase in Qmax during the entire follow-up period after HoLEP was greater than that after PVP, except for that at one month and 36 months after the surgeries (Fig. 2). However, no significant differences were found in the postoperative changes in the other outcome parameters (SSS, PVR, and BVE) compared with that at baseline between the two groups throughout the entire follow-up period after surgery. The degree of decrease in the serum PSA level at each follow-up visit after HoLEP was generally greater than that after PVP.

Influential factor of QoL improvement after PVP or HoLEP

According to logistic regression (LR) analyses, univariate analysis showed that the serum PSA level, preoperative prostate volume, baseline SSS, BCI, BOOI on baseline urodynamic study (UDS), operation time, and energy applied during surgery were associated with QoL improvement at one year after surgery. Multivariate analysis revealed that lower baseline SSS and higher BOOI were independent factors influencing QoL improvement at the short-term follow-up visit after surgery (Table 3). In terms of influential factors of QoL improvement at the mid-term follow-up visit, the univariate model showed that the preoperative prostate volume, BOOI on baseline UDS, operation time, and energy applied during surgery were associated with QoL improvement at three years after surgery. However, on multivariate analysis, no independent factor influenced QoL improvement at that time (Table 3). Regarding influential factors of QoL improvement at the long-term follow-up visit, univariate analysis revealed no factor influencing QoL improvement at five years after surgery. The surgical methods were not associated with QoL improvement at any time point of follow-up after surgery (Table 3).

Discussion

Because LUTS strongly influences QoL negatively2,4, one of the goals for the treatment of BPH was focused on improving QoL16. Laser surgery for BPH has been expected to be alternatives to the gold standard of BPH surgery (TURP or open prostatectomy) because, compared with TURP, it showed comparable efficacy and lower postoperative morbidity as mentioned above11,17. Specifically, Xue et al. reported that PVP provided equivalent efficacy and fewer bleeding complications for 3 years after surgery, compared with TURP18. HoLEP, an enucleation surgery for BPH, was reported to have similar efficacy and lower perioperative complications with a significant level of evidence, than TURP8. However, there has been a scarcity of studies mainly focusing on QoL improvement after laser prostatectomy. Because the treatment outcomes of BPH surgery greatly affect patients’ QoL, this study may extend the current knowledge regarding them. The results of our study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

Postoperative improvement of QoL was maintained up to the long-term follow-up period after PVP or HoLEP.

- (2)

No significant differences were found between the two groups in postoperative changes from baseline of the QoL index during the 48-month follow-up period after surgery. However, the degree of improvement in QoL at 60 months after HoLEP was greater than that after PVP.

- (3)

Lower baseline SSS and higher BOOI were independent factors influencing QoL improvement at the short-term follow-up visit after surgery. However, because the follow-up duration was longer, no independent factor influenced QoL improvement at the mid- and long-term follow-up visits after surgery.

Our study has shown that the postoperative improvement of QoL was maintained up to the long-term follow-up period, irrespective of the type of laser surgery. In agreement with our results, Xue et al. reported that the postoperative improvement of QoL was sustained up to 36 months after TURP or PVP-120 W-HPS18. Additionally, Gilling et al. compared the surgical outcomes at 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 92 months between TURP and HoLEP19. According to their results, the postoperative improvement of QoL was maintained up to 92 months after TURP and HoLEP, without a difference between the two surgeries19. Meanwhile, although laser surgery is expected to have a positive effect on the postoperative improvement of QoL in men with BPH, few studies have focused on the comparative analysis of serial long-term treatment outcomes for QoL between PVP and HoLEP. Previously, a minority of studies showed no difference in the postoperative improvement of QoL at one year after surgery between PVP using 120 W HPS and HoLEP14,15. Interestingly, our study with long-term follow-up data showed that the degree of improvement in the QoL index at 60-month follow-up visits after HoLEP might be superior to that after PVP, perhaps in part because of a difference in the long-term durability of surgical outcomes. This result could be supported by our finding that the degree of improvement in voiding symptoms, peak flow rate or reduction in the serum PSA level at the long-term follow-up visits after HoLEP was higher than that after PVP. In accordance with these findings, recent literature by Hermann et al. noted that transurethral endoscopic enucleation of the prostate, such as HoLEP, offer some advantages in terms of morbidity8,13. However, further long-term follow-up studies comparing PVP using the 180 W XPS laser and HoLEP are necessary to draw a solid conclusion because PVP using the 180 W XPS laser has recently been performed in men with BPH.

Interestingly, according to our data, the degree of improvement in voiding symptoms during the early postoperative period (1 to 3 months) after PVP or HoLEP was much greater than that in storage symptoms. Thus, storage symptoms appear to improve gradually with time after surgery, whereas voiding symptoms do dramatically from the immediate postoperative period after surgery. This may be attributed to an irritative effect of laser vaporization despite enucleation during laser prostatectomy. Thus, laser energy applied during laser prostatectomy might be beneficial with respect to hemostasis, but some patients could pay the price of postoperative storage or irritative symptoms in the early postoperative period. The irritative effect may have impacts on the surgical outcome for storage symptoms in the early postoperative period. In accordance with this, Cindolo et al. showed that transient storage symptoms were developed more frequently after GreenLight enucleation of the prostate than after standard PVP or anatomic PVP20. They suggested that this might be due to microinjury of capsules and per-capsule innervation caused by more coagulation in the capsular bleeding spot in GreenLight enucleation of the prostate20.

A factor to be considered when evaluating the surgical outcomes of PVP or HoLEP is the surgeon’s expertise. Particularly regarding the learning curve of HoLEP, some literature has shown that HoLEP has a steep learning curve with a stationary state at 20–50 cases21,22. Accordingly, when the learning curve for the efficiency of HoLEP was assessed by enucleation efficiency (a ratio of retrieved tissue weight/enucleation time) in our study, the enucleation efficiency appeared to be stationary after approximately 50 cases (Supplementary Fig. S1B). According to a recent study by Castellan et al. that analyzed a learning curve of PVP using the 180 W XPS laser, surgeons with greater experience in endoscopic procedure showed a lower rate of early complications and greater evolution in lasing time/operation time ratio than those with lesser experience23. However, there was no significant difference in the functional outcomes at 6 months after surgery between the groups23. In the present study, when the learning curve for the efficiency of PVP was assessed by the ratio of the removed prostate volume/operation time, the PVP efficiency seemed to be stationary even in the first case. Furthermore, the PVP efficiency was further evolved after approximately 150 cases. The cause might be that the surgeon (HS) in our study had sufficient experience in endoscopic surgery for BPH. However, it is difficult to directly compare the studies because of differences in the baseline characteristics and study populations, as well as in definitions of learning curve.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that reported the factors influencing the postoperative improvement of QoL serially at the short-term, mid-term, and long-term follow-up visits after PVP or HoLEP. Our LR analyses showed that a lower baseline SSS and a higher BOOI were independent factors influencing postoperative QoL improvement at the short-term follow-up visit after PVP or HoLEP. Given that BPH surgeries such as PVP and HoLEP have been designed to relieve BOO, it may be reasonable to assume that patients with a higher BOOI have a higher probability of improvement in QoL after surgery. In accordance with our result, Ryoo et al. showed that a BOOI greater than 40 was a predictor of treatment success, including QoL at six months after HoLEP24. Additionally, the patients with less severe storage symptoms before surgery appear to have a higher possibility of postoperative improvement in QoL, perhaps because, as our data showed, the lower baseline SSS was significantly correlated with a lower SSS and a lower QoL index at one year after PVP or HoLEP (Spearman’s correlation coefficient = 0.390 and 0.253, respectively). Interestingly, based on univariate analysis, several factors, including a higher BOOI and preoperative prostate volume, were associated with postoperative QoL improvement at the mid-term follow-up visit, no independent factor of QoL improvement was found on multivariate analysis. Furthermore, no influential factor of QoL improvement was found at the long-term follow-up visit, even on univariate analysis. Thus, postoperative QoL improvement at the short-term follow-up period after PVP or HoLEP appears to be maintained up to five years, without any specific factor influencing its improvement at the mid-term or long-term follow-up visit.

There are a few limitations in our study. First, because our study was retrospective, there were differences in a few baseline parameters between the two groups. Second, we used PVP using 120 W-HPS; however, in 2010, PVP using 180 W-XPS was introduced. In the future, long-term follow-up studies comparing PVP using the 180 W XPS laser and HoLEP are necessary to validate our result, although the long-term follow-up data of PVP using 180 W-GreenLight XPS might still be limited. Nevertheless, our data have some clinical implications to understand the outcomes of QoL-related LUTS after laser prostatectomy, such as PVP or HoLEP. Our results may help effectively counsel patients about expectations for two representative laser prostatectomies or surgical outcomes for QoL related to LUTS. Additionally, our results may be used to counsel patients on which ones can benefit the most from PVP or HoLEP in terms of QoL-related LUTS, particularly at the short-term follow-up period after surgery.

In conclusion, our data confirm that both PVP and HoLEP have durable efficacy in QoL improvement throughout the five-year follow-up period. HoLEP might provide more improvement in QoL at the long-term follow-up point than PVP. A lower baseline SSS and a higher BOOI appear to independently influence QoL improvement at the short-term follow-up visit after PVP or HoLEP. When the follow-up duration is longer, no factor appears to influence QoL improvement independently at the mid- and long-term follow-up visits. Subsequent prospectively controlled comparative studies with a larger study population and a long-term follow-up on PVP using 180 W GreenLight XPS and HoLEP would be needed to validate our findings.

Materials and Methods

Study population, data and design

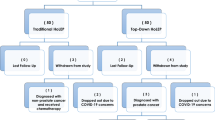

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at both Seoul National University and Seoul Metropolitan Government Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center. All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The need for written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of this study. We retrospectively reviewed the data of 1,569 patients who had undergone PVP-120 W-HPS (n = 564) or HoLEP (n = 1,005) because their LUTS/BPH was unresponsive to medications from January 2008 to March 2014 at our institution. We excluded 320 patients with previously diagnosed urethral stricture, cancer of the bladder or prostate or urethra, history of other urologic surgeries, or incomplete data. Among the remaining 1,249 patients, 1,193 patients (PVP group, n = 439; HoLEP group, n = 754) with a baseline QoL of the I-PSS of at least 2 before surgery were included in this study.

Before the surgeries, all patients received preoperative evaluations for LUTS secondary to BPH, including medical history, physical examinations, the I-PSS, urinalysis, serum PSA, transrectal ultrasound for prostate, and a multichannel UDS. A surgical method, either PVP or HoLEP, was chosen based on the surgeon’s preference. PVP was performed by a single surgeon (HS) as described in a previous study25. Briefly, PVP was performed using the planned vaporization-resection technique, with a 120 W GreenLight HPS laser at a setting of 80 W for vaporization-resection and 100 W for vaporization. HoLEP was performed by one of two surgeons (JSP or SJO) in the usual manner as previously mentioned26. Briefly, enucleation was performed mainly using three-lobe techniques with a 26 Fr resectoscope, a 550-μm laser fiber, or an 80-W holmium:YAG laser at a setting of 2 J 50 Hz or 2 J 40 Hz. Morcellation of the enucleated prostatic adenoma was performed with a morcellator. The patients received follow-up visits serially at 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 months after surgery. At each follow-up visit, the patients were evaluated for the I-PSS, serum PSA, and uroflowmetry.

We defined ‘QoL improvement’ as a reduction of 50% or more in the QoL index at each follow-up visit compared with that at the baseline to investigate patients with a definite effect after surgery to confirm strong factors leading to favorable outcomes. Bladder voiding efficiency (BVE) was equated as (voided volume) × 100/(voided volume + PVR).

Statistical analysis

To compare the preoperative characteristics and surgical outcomes between PVP and HoLEP, we used independent t-test and chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test. For comparisons between baseline variables and postoperative outcome parameters, we used paired t-test. Additionally, the repeated-measures ANOVA test was performed to adjust for the impact of time on the QoL outcomes. To identify the factors influencing the ‘QoL improvement’ at the short-term (one year after surgery), mid-term (three years after surgery), and long-term (five years after surgery), we applied LR analyses. Variables with p < 0.05 in the univariate LR were included in multiple LR. p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant in all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 21.0.

Data Availability

The analyzed data sets of this study can be reasonably requested from the corresponding author.

Change history

08 November 2019

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Berry, S. J., Coffey, D. S., Walsh, P. C. & Ewing, L. L. The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol 132, 474–479 (1984).

Seki, N. et al. Association among the symptoms, quality of life and urodynamic parameters in patients with improved lower urinary tract symptoms following a transurethral resection of the prostate. Neurourol Urodyn 27, 222–225, https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20466 (2008).

Cornu, J. N. Bipolar, Monopolar, Photovaporization of the Prostate, or Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate: How to Choose What’s Best? Urol Clin North Am 43, 377–384, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2016.04.006 (2016).

Fwu, C. W. et al. Long-term effects of doxazosin, finasteride and combination therapy on quality of life in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 190, 187–193, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.061 (2013).

Garraway, W. M. & Kirby, R. S. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: effects on quality of life and impact on treatment decisions. Urology 44, 629–636 (1994).

DerSarkissian, M. et al. Comparing Clinical and Economic Outcomes Associated with Early Initiation of Combination Therapy of an Alpha Blocker and Dutasteride or Finasteride in Men with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 22, 1204–1214, https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.10.1204 (2016).

Djavan, B. et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: current clinical practice. Prim Care 37, 583–597, ix, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2010.04.004 (2010).

Naspro, R. et al. From “gold standard” resection to reproducible “future standard” endoscopic enucleation of the prostate: what we know about anatomical enucleation. Minerva Urol Nefrol 69, 446–458, https://doi.org/10.23736/S0393-2249.17.02834-X (2017).

Hueber, P. A. & Zorn, K. C. Canadian trend in surgical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia and laser therapy from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012. Can Urol Assoc J 7, E582–586, https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.203 (2013).

Archer, S. et al. Surgery, Complications, and Quality of Life: A Longitudinal Cohort Study Exploring the Role of Psychosocial Factors. Ann Surg, https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002745 (2018).

Cornu, J. N. et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Functional Outcomes and Complications Following Transurethral Procedures for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Resulting from Benign Prostatic Obstruction: An Update. Eur Urol 67, 1066–1096, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.017 (2015).

Brassetti, A. et al. Green light vaporization of the prostate: is it an adult technique? Minerva Urol Nefrol 69, 109–118, https://doi.org/10.23736/S0393-2249.16.02791-0 (2017).

Herrmann, T. R. Enucleation is enucleation is enucleation is enucleation. World J Urol 34, 1353–1355, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-016-1922-3 (2016).

Elzayat, E. A., Al-Mandil, M. S., Khalaf, I. & Elhilali, M. M. Holmium laser ablation of the prostate versus photoselective vaporization of prostate 60 cc or less: short-term results of a prospective randomized trial. J Urol 182, 133–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.117 (2009).

Elmansy, H. et al. Holmium laser enucleation versus photoselective vaporization for prostatic adenoma greater than 60 ml: preliminary results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Urol 188, 216–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.2576 (2012).

Madersbacher, S. et al. EAU 2004 guidelines on assessment, therapy and follow-up of men with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction (BPH guidelines). Eur Urol 46, 547–554, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2004.07.016 (2004).

Zang, Y. C. et al. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate with GreenLight 120-W laser versus transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lasers Med Sci 31, 235–240, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-015-1843-1 (2016).

Xue, B. et al. GreenLight HPS 120-W laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a prospective randomized trial. J Xray Sci Technol 21, 125–132, https://doi.org/10.3233/XST-130359 (2013).

Gilling, P. J. et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial comparing holmium laser enucleation of the prostate and transurethral resection of the prostate: results at 7 years. BJU Int 109, 408–411, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10359.x (2012).

Cindolo, L., Ruggera, L., Destefanis, P., Dadone, C. & Ferrari, G. Vaporize, anatomically vaporize or enucleate the prostate? The flexible use of the GreenLight laser. Int Urol Nephrol 49, 405–411, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-016-1494-6 (2017).

Robert, G. et al. Multicentre prospective evaluation of the learning curve of holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP). BJU Int 117, 495–499, https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13124 (2016).

Kampantais, S. et al. Assessing the Learning Curve of Holmium Laser Enucleation of Prostate (HoLEP). A Systematic Review. Urology 120, 9–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2018.06.012 (2018).

Castellan, P. et al. The Surgical Experience Influences the Safety and Efficacy of Photovaporization of Prostate with 180-W XPS GreenLight Laser: Comparison Between Novices vs Expert Surgeons Learning Curves. J Endourol 32, 1071–1077, https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2018.0437 (2018).

Ryoo, H. S. et al. Efficacy of Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate Based on Patient Preoperative Characteristics. Int Neurourol J 19, 278–285, https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.2015.19.4.278 (2015).

Yoo, S. et al. A novel vaporization-enucleation technique for benign prostate hyperplasia using 120-W HPS GreenLight laser: Seoul technique II in comparison with vaporization and previously reported modified vaporization-resection technique. World J Urol 35, 1923–1931, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-017-2091-8 (2017).

Kim, M., Lee, H. E. & Oh, S. J. Technical aspects of holmium laser enucleation of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Korean J Urol 54, 570–579, https://doi.org/10.4111/kju.2013.54.9.570 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.S. carried out substantial contributions to the conception/design, data acquisition, data analysis, interpretations, drafting of the manuscript and statistical analysis. S.Y. carried out substantial contributions to the conception/design, data acquisition, data analysis, interpretations and statistical analysis. J.P., S.Y.C., H.J. carried out data analysis and data interpretation. H.S., S.J.O. and J.S.P. carried out substantial contributions to the data acquisition, data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. M.C.C. carried out substantial contributions to the conception/design, data interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, supervision and final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, I., Yoo, S., Park, J. et al. Quality of life after photo-selective vaporization and holmium-laser enucleation of the prostate: 5-year outcomes. Sci Rep 9, 8261 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44686-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44686-2

This article is cited by

-

Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate: efficacy, safety and preoperative management in patients presenting with anticoagulation therapy

World Journal of Urology (2021)

-

Comparison of 532-nm GreenLight HPS laser with 980-nm diode laser vaporization of the prostate in treating patients with lower urinary tract symptom secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: a meta-analysis

Lasers in Medical Science (2021)

-

Holmium laser technologies versus photoselective greenlight vaporization for patients with benign prostatichyperplasia: a meta-analysis

Lasers in Medical Science (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.