Abstract

Energy storage performances of Ni-based electrodes rely mainly on the peculiar nanomaterial design. In this work, a novel and low-cost approach to fabricate a promising core-shell battery-like electrode is presented. Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains were obtained by an electrochemical oxidation of a 3D nanoporous Ni film grown by chemical bath deposition and thermal annealing. This innovative nanostructure demonstrated remarkable charge storage ability in terms of capacity (237 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1) and rate capability (76% at 16 A g−1, 32% at 64 A g−1). The relationships between electrochemical properties and core-shell architecture were investigated and modelled. The high-conductivity Ni core provides low electrode resistance and excellent electron transport from Ni(OH)2 shell to the current collector, resulting in improved capacity and rate capability. The reported preparation method and unique electrochemical behaviour of Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains show potential in many field, including hybrid supercapacitors, batteries, electrochemical (bio)sensing, gas sensing and photocatalysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

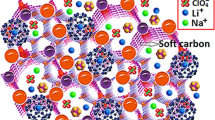

The growing world energy demand, the finite supply of fossil fuels and the climate change due to detrimental gas emission have attracted a great attention of researchers in renewable energy resources and related energy storage technologies. A large variety of energy storage devices has been developed so far, including batteries and supercapacitors1. Batteries store energy through diffusion controlled redox reactions in bulk electrode material, leading to high energy density. However, the low power density of batteries hinders their use in applications where high power is required. On the other hand, supercapacitors bridge the gap between conventional capacitors and batteries, providing energy density higher than conventional capacitors and power density higher than batteries2. Recently, novel supercapacitor-battery hybrid systems, namely, hybrid supercapacitors, have received increasing interest since they combine the high power density of a supercapacitor-like material (negative electrode) with the high energy density of a battery-like material (positive electrode)3.

Among the more investigated positive electrodes for hybrid supercapacitors are NiO and Ni(OH)2 owing to their low-cost, well-defined redox reactions, environmental friendliness, and high theoretical capacity (359 and 289 mAh g−1, respectively)4. It is worth noting that these materials exhibit the typical electrochemical features of batteries, and then the most significant feature is the specific capacity [mAh g−1]5,6. Nonetheless, they are often described in terms of specific capacitance [F g−1] which doesn’t allow a straightforward comparison in literature4.

The more efficient strategy to obtain high-capacity NiO and Ni(OH)2 electrode is to fabricate nanostructured materials. In fact, it has been demonstrated that NiO and Ni(OH)2-based nanostructures possess superior electrochemical properties due to their high surface to volume ratio, efficient electrolyte penetration and low resistance7. Over the past years, 0D (nanoparticles8), 1D (nanowires9), 2D (nanosheets10) and 3D (flower-like structure11, nanowalls12) nanostructures have been developed. Among them, 3D materials are the more advantageous ones, since their better connectivity results in higher electrical conductivity and improved mechanical stability13. In particular, 3D Ni(OH)2 nanowalls is considered one of the best electrode since it adds the advantage of a unique open nanoporous structure formed by a tight network of nanosheets (20 nm thick, 0.1 ÷ 2 μm height) with excellent flexibility12. Also, Ni(OH)2 nanowalls can be prepared by a simple, low-cost, low-temperature and large-area chemical bath deposition process (CBD)7. Despite these promising features, only a few nanostructures have a capacity close to the theoretical one4. Moreover, most of them suffer from poor rate capability, since capacity dramatically reduces at the high charge-discharge rates required for high power applications. This is commonly attributed to the poor electrical conductivities of NiO and Ni(OH)2-based materials13. An effective approach to improve the rate capability of NiO and Ni(OH)2 nanostructures is to deposit them onto highly conductive current collectors, such as Ni nanotubes arrays14, graphene nanosheets15, carbon nanotubes16, and carbon coated 3D copper structure17. Another favourable strategy is based on core-shell nanostructures which take advantage of the synergistic properties offered by the two components (electrochemically active shell, and high-conductivity core). Semiconductive (3D TiO2 nanowires arrays18) and metallic (3D Ni nanoparticles19 and Ni nanotubes arrays20) cores have been reported. However, a simple and cost-effective approach to fabricate core-shell nanostructured electrodes with high capacity and rate capability is still absent, limiting their transfer to commercial products4,13. Moreover, the effects of the conductive core on the charge storage process have not been fully clarified yet. Therefore, a detailed comprehension of the electrochemical behaviour of core-shell structures could lead to an effective improvement of the energy storage performances of these materials.

In this work, we present a simple and low-cost approach to fabricate a novel Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains with superior specific capacity and rate capability. The relationships between electrochemical properties and core-shell structure are investigated and modelled. The innovative design of Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains has potential applications in hybrid supercapacitors, lithium-ion batteries, electrochemical (bio)sensing, gas sensing and photocatalysis.

Methods

Synthesis

Ni foam substrates (1 × 1.5 cm2, Goodfellow, thickness 1.6 mm, porosity 95%, 20 pores cm−1) were rinsed with acetone, isopropanol and deionized water (MilliQ, 18 MΩ cm), and dried under N2 gas flow. Ni-based nanostructures were grown on cleaned substrates by chemical bath deposition (CBD). Solution for CBD was prepared by mixing 0.42 M NiSO4·6H2O (Alfa Aesar, 98%), 0.07 M K2S2O8 (Alfa Aesar, 97%) and 3.5 wt% ammonia (Merck, 30–33 wt% NH3 in H2O). The solution was heated up to 50 °C and kept at this temperature through a bain-marie configuration21. Substrates were immersed (1 × 1 cm2 area) in the solution for 20 min. Then, the samples were rinsed with deionized water to clean deposited film from unwanted microparticulate and dried in N2 gas. Some samples were further annealed at 350 °C for 60 min in Ar followed by 60 min in forming gas (FG, Ar:H2 95:5 mixture). Finally, an electrochemical oxidation of the annealed films surface was performed by cyclic voltammetry (CV) (100 cycles in the potential range −0.2 ÷ 0.8 V at 50 mV s−1 scan rate).

Film mass after each synthesis step was measured with a Mettler Toledo MX5 Microbalance (sensitivity: 0.001 mg). Before weighing, samples were washed several times with deionized water, dried in N2 gas and put in an oven at 60 °C for 1 h.

Characterization

The surface morphology of samples was characterized by using a Scanning Electron Microscope (Gemini field emission SEM Carl Zeiss SUPRA 25) while the structural and chemical properties of samples were investigated by Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL JEM-2010F TEM) operating at 200 keV accelerating voltage. Samples for TEM observation were prepared by standard TEM specimen preparation techniques by using a flat Ni substrate.

Electrochemical oxidation process and measurements were performed at room temperature by using a potentiostat (VersaSTAT 4, Princeton Applied Research, USA) and a three-electrode setup with a platinum counter electrode, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as reference, Ni-based nanostructures as working electrodes (1 × 1 cm2 immersed area), in 1 M KOH (Sigma Aldrich, ≥85%) supporting electrolyte. CV curves were recorded at different scan rates (1 to 50 mV s−1) in the potential range −0.2 ÷ 0.8 V. Galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) tests were conducted at different current densities (1 to 64 A g−1) in the potential range 0 ÷ 0.4 V. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed at 0 V vs open circuit potential with a superimposed 5 mV sinusoidal voltage in the frequency range 104–10−2 Hz.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains

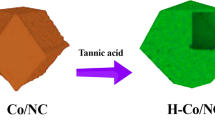

A conductive core is required to enable faster electron transfer, and thus high-rate performance electrode. In this work a Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains was obtained by a three-step synthesis shown in Fig. 1. The 50 °C CBD leads to a Ni(OH)2 nanowalls structure with thin (~10 nm) sheets mostly perpendicular to the substrate. Figure 2(a,b) report the SEM images at different magnifications of the film grown by CBD, which shows the typical morphological features of Ni(OH)2 nanowalls.

A reducing thermal process leads to a structural and chemical transformation. As shown in Fig. 2(c,d), Ni(OH)2 nanowall shaped film was transformed into chain-like clusters of metallic Ni nanoparticles (20–30 nm in size). XRD patterns before and after annealing confirmed the Ni(OH)2 → Ni transformation22.

An electrochemical process is finally used to obtain the core-shell structure. Figure 3 reports the CV curves recorded during the electrochemical oxidation of the Ni nanoparticles. Two pronounced oxidation and reduction peaks appeared with increasing cycle number, which are attributed to the redox couple Ni2+/Ni3+. In fact, first Ni(OH)2 is formed because of the reaction between Ni nanoparticles surface and OH− ions in solution23:

Then, the following reversible redox reaction occurs:

Peaks area enlargement with cycling is due to the increasing Ni(OH)2/NiOOH volume. The electrochemical oxidation was stopped after 100 CV cycles since almost stable curves were obtained (Fig. S1).

Transmission electron microscopy analyses were performed to investigate the crystallinity of Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains. Figure 4(a) reports a bright field image of the sample, displaying some bunches of nanoparticles with diameters ranging between 20–30 nm (a low-magnification image which shows the chain-like structure of the sample is reported in Fig. S2). The high resolution TEM (HR-TEM) image in the inset clearly demonstrates the core-shell structure, showing a 20 nm large nanoparticle surrounded by a 3–4 nm thin shell. The core presents a set of family planes with fringes separated by a distance equal to 1.8 Å while the shell displays two different family planes whose interplanar distance is equal to 2.1 and 2.3 Å. Such interplanar distances are compatible with the {200} Ni (1.8 Å), with the {200} NiO (2.1 Å) and the {101} Ni(OH)2 (2.3 Å), respectively. Selected Area Electron Diffraction ring-like patterns, acquired from the same region, are shown in the insets in Figs 4(b,c) and denote the polycrystalline nature of the sample. These results confirm the presence of the {200} Ni planes and the {200} and {220} NiO planes14. To better distinguish Ni from NiO domains, dark field images were acquired by putting the TEM objective aperture in correspondence of both the {200} Ni and {200} NiO diffracting rings (Fig. 4(b)) and in correspondence of the {220} NiO ring (Fig. 4(c)) in the SAED pattern. All images shown in Fig. 4 were acquired form the same region of TEM sample. It should be underlined that even by employing the smallest TEM objective aperture it was not possible to separate ring-like patterns corresponding to {200} Ni and {200} NiO, whose distance in the SAED is smaller than the objective aperture diameter (see the inset in Fig. 4(b)). Both large (~20 nm) and small (~3–4 nm) crystalline grains show high contrast in Fig. 4 (b) while Fig. 4(c) put in evidence only the presence of the small ones. In particular the large particle underlined in Fig. 4(b) is not visible in Fig. 4(c) where it appears surrounded by small nanocrystals. Moreover, the size of the large grains is consistent with that of the Ni nanoparticles, while the size of the small ones is comparable with the thickness of the NiO/Ni(OH)2 shell. In conclusion, this dark field visibility behaviour allows us strongly support that these core-shell nanostructures are formed by Ni crystalline grains surrounded by a ~3–4 nm NiO/Ni(OH)2 shell.

Finally, it worth to be noted that both high resolution and dark field techniques are sensitive to the crystallography of nanomaterials thus, to strongly support the conclusions drawn so far, a chemical analysis at the nanoscale was conducted by means of STEM-Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (STEM-EELS) applied to about a ten of nanoparticles. First of all, the high energy EELS spectrum of each nanoparticle was acquired; as expected it shows the edge at 532 eV corresponding to the OK ionization shell and the edge at 855 eV corresponding to the NiL shell (Fig. 5(a)). Secondly, the elemental mapping of Ni and O was generated on the base of this spectrum (Fig. 5(b)). It clearly demonstrates that the core shell structure is composed by a Ni core (in blue colour) surrounded by a uniform NiO shell (in yellow), in strong agreement with the HR-TEM investigation.

According to mass measurements (more details in the Supplementary Information), it was estimated that 36% Ni of Ni nanoparticles was consumed to form the Ni(OH)2 shell. The remaining Ni atoms (64%) constitute the highly conductive 3D backbone.

Electrochemical properties of core-shell and nanowalls electrodes

CV was employed to identify the storage mechanism of Ni(OH)2 nanowalls (“nanowalls”) and Ni(OH)2 core-shell nanochains (“core-shell”) electrodes. Figure 6 compares the CV curves of the two samples at 1 mV s−1 scan rate in 1 M KOH. Both curves are very distinct from the classic rectangular shape of EDLCs and pseudocapacitors, showing instead the characteristic faradaic redox peaks of battery-like materials4,5,6.

The inset in Fig. 6 reports an enlarged scale of the oxidation peaks, revealing clear differences among the two electrodes. The peak of nanowalls (top inset) was fitted by a three-component model: peak 1 at ~0.320 V, peak 2 at ~0.360 V and peak 3 at ~0.410 V. Instead, the oxidation peak of core-shell (bottom inset in Fig. 6) was fitted by a two-component model: peak 1 at ~0.310 V, and peak 2 at ~0.340 V. Typically, CV peaks of Ni-based electrodes are associated to the redox reactions α-Ni(OH)2 ↔ γ-NiOOH and β-Ni(OH)2 ↔ β-NiOOH24,25. α-Ni(OH)2 is oxidized to γ-NiOOH at a lower potential than β-Ni(OH)2 oxidized to β-NiOOH26. Therefore, it can be reasonably concluded that peak 1 is related to γ-NiOOH formation, while peak 2 and 3 are related to β-NiOOH formation. Consequently, the reduction peak of nanowalls (~0.180 V) and core-shell (~0.210 V) is attributed to the totally overlapped components of α-Ni(OH)2 and β-Ni(OH)2 formation.

CV curves were also recorded at higher scan rates (Fig. S3). The shape of core-shell CV does not change significantly with increasing scan rate. This suggests a lower equivalent series resistance (ESR), which is the combined resistance of electrolyte and internal resistance of the sample17. As the scan rate increases, the oxidation and reduction peaks shift toward more positive and negative values, respectively. However, core-shell always presents a smaller separation among oxidation and reduction peaks than nanowalls, which is commonly associated to a better redox reversibility24.

The specific capacity (electrode capacity/mass of the active material, [mAh g−1]) is the more informative property to describe and compare the energy storage ability of different materials. Therefore, accurate mass measurements are required4. In this work particular care has been taken in evaluating the mass, and the obtained results are reported in Table S1. GCD tests at different current densities (Fig. S4) were performed to evaluate the specific capacity of the nanowalls and core-shell electrodes. Figure 7(a) compares the discharge profiles of the two samples at 16 A g−1. A voltage plateau is present in both curves, confirming the battery-like behaviour resulted from CV4,5,6. The voltage drop (IR drop) at the beginning of the discharge curves results from the ESR, which is the main contribution to energy and power loss at high charge-discharge rate. Core-shell clearly shows a lower IR drop, and thus a smaller ESR in agreement with CV measurements.

The specific capacity Qs [mAh g−1] of the samples was calculated by4

where I is the constant current density [A cm−2], Δt is the discharge time [s] and m is the mass of the active material [g cm−2]. Figure 7(b) reports the specific capacity as function of the current density for the two electrodes. The specific capacity decreases with increasing current density. However, the nanowalls electrode shows a specific capacity of 176 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1 and 63 mAh g−1 at 16 A g−1, retaining 36%. Instead, the core-shell electrode shows a specific capacity of 237 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1 and 180 mAh g−1 at 16 A g−1, retaining 76%. The superior rate capability of core-shell enabled even higher current densities. In particular, at the high current density of 64 A g−1 the specific capacity of core shell was still higher than that of nanowalls at 16 A g−1.

Specific capacity was also calculated from CV measurements (Fig. S5). The obtained results are consistent with those of GCD tests, indicating that core-shell has a superior charge storage ability, especially when high charge-discharge rates are considered.

The electrochemical utilization \(z\) [%] of the active material can be calculated from GCD tests according to the equation27

where Qs is the specific capacity [C g−1], \({M}_{Ni{(OH)}_{2}}\) is the molar mass of Ni(OH)2 (92.7 g mol−1) and F is the Faraday constant (96485 C mol−1). \(z={\rm{100}} \% \) means that the whole active material undergoes redox reactions. The \(z\) values of the two samples at different current densities are reported in Table 1. At 1 A g−1 61% Ni(OH)2 in nanowalls and 82% in core-shell are used respectively. Such a difference is even more pronounced at higher current densities, as expected from Fig. 7(b). In fact, at 16 A g−1 only 22% Ni(OH)2 in nanowalls is used, while 62% in core-shell is still involved in the redox process. This result suggests an improved electrochemical utilization of the active material in core-shell.

Ni-based electrodes suffer from significant capacity decay during charge-discharge cycles because redox reactions are involved2. Since a long cycling stability is critical for industrial applications, a stability test was performed by 1000 GCD cycles at the high current density of 16 A g−1. Figure 8 compares the cycling characteristics of the nanowalls and core-shell electrodes. After 1000 cycles the nanowalls electrode presents a specific capacity of 43 mAh g−1, retaining 68% of the initial value. The capacity decay can be explained by the growth of crystals size, leading to decrease in surface area, and to Ni(OH)2 flaking off caused by the volume change during charge-discharge as confirmed by SEM analysis after cycling tests (Fig. S6)26. Instead, the core-shell electrode shows first a rise in specific capacity (1–300 cycles) attributed to the fully activation of the Ni cores, followed by a decay (300–800 cycles), and finally a nearly constant capacity (800–1000 cycles). The capacity decay from cycle 300 to 1000 can’t be ascribed to morphological variations as demonstrated by SEM analysis after cycling tests (Fig. S6). To explain this behaviour it should be noted that α-Ni(OH)2 ↔ γ-NiOOH contributes more than β-Ni(OH)2 ↔ β-NiOOH to the core-shell energy storage process (inset in Fig. 6). However, α-Ni(OH)2 is unstable in water and typically recrystallizes into β-Ni(OH)2 with cycling25,28. Moreover, β-Ni(OH)2 ↔ β-NiOOH has a lower theoretical capacity than α-Ni(OH)2 ↔ γ-NiOOH26,29. Therefore, it can be reasonably concluded that the α-Ni(OH)2 → β-Ni(OH)2 transformation is responsible for the core-shell capacity decay. The complete transformation into β-Ni(OH)2 after 800 cycles determines a nearly constant capacity of 149 mhA g−1 (83% of the initial value). This value is higher than specific capacitance of nanowalls after 1000 cycles, indicating a better cycling stability of the core-shell electrode.

Discussion

To consolidate the improved energy storage properties of the core-shell sample, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analyses were performed. Figure 9 compares the Nyquist plots of nanowalls and core-shell obtained from EIS experiments, with an enlarged scale for core-shell at high frequencies (inset). The two plots show a semicircle arc in the high-frequency region, and a straight line in the low-frequency region. This shape can be modelled by the equivalent circuit reported in Fig. 9. The slopes of the two lines at low frequencies are similar, indicating a low ions diffusion resistance and a behaviour close to that of an ideal capacitor (line parallel to the imaginary axis). The ESR can be evaluated as the intercept on the real axis of the Nyquist plot. The lower ESR of core-shell (~1.2 Ω) than nanowalls (~1.7 Ω) is due to the presence of Ni cores, which leads a smaller IR drop in the discharge curves for fixed current density (Fig. 7(a)). The charge transfer resistance (Rct) can be measured as the diameter of the semicircle in the high-frequency region. It can be seen that core-shell has a lower Rct (~0.1 Ω) than nanowalls (~5.4 Ω).

Nyquist plot of the nanowalls (red open squares) and core-shell (blue spheres) samples recorded at 0 V vs open circuit potential with a 5 mV superimposed AC voltage in the frequency range 104 ÷ 10−2 Hz in 1 M KOH solution (the inset is the magnified high-frequency region of the core-shell electrode). Equivalent circuit model for the Nyquist plots is also reported: an equivalent series resistance (ESR) is connected in series with a constant phase element (CPE1) in parallel with the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and a constant phase element (CPE2)14.

To further support the excellent electrochemical behaviour of the core-shell, the electric field in the nanowalls and core-shell electrodes was simulated by using the COMSOL Multiphysics software (more details in the Supplementary Information). The resulted electric field module distributions are presented in Fig. 10 in false colour scale from 0 to 1.5 × 108 V m−1. Nanowalls (left), displays a moderate electric field (~0.4 × 108 V m−1) near the nanosheet/substrate interface, which is dramatically reduced going far away from the substrate. Instead, the conductive Ni core in core-shell (right) provides a uniform and enhanced electric field (~0.8 × 108 V m−1) along the entire shell, in agreement with the improved electrochemical utilization reported in Table 1.

Electric field module distribution of the nanowalls (left) and core-shell (right) electrodes in 1 M KOH solution for 0.4 V applied bias, as simulated by COMSOL Multiphysics software. A 20 nm thick Ni(OH)2 nanosheet was used to simulate the nanowalls electrode. A 17 nm thick Ni nanosheet surrounded by a 3 nm thick Ni(OH)2 shell was used to simulate the core-shell electrode. The following room temperature conductivities were used: 10−13 S cm−1 for Ni(OH)2, 105 S cm−1 for Ni, and 0.2 S cm−1 for 1 M KOH28,36.

On the basis of the aforementioned results, the following model was developed to explain the improved specific capacity, rate capability and cycling stability of Ni(OH)@Ni core-shell nanochains. i) Ni cores reduce electrode resistance (thus energy dissipation) and charge-transfer resistance. Moreover, they enhance the electric field in the whole Ni(OH)2 shell. These features result in higher charge storage ability and faster redox process. ii) the 3 nm thin Ni(OH)2 shell shortens the electrons migration paths from the surface of the active material to the current collector (schematic illustration in Fig. 11). Also, a high OH− ions diffusion coefficient of (1.415 ± 0.002) × 10−6 cm2 s−1 was estimated for the core-shell electrode according to the Randles-Sevcik equation (more details in the Supplementary Information), which is higher than 2.491 × 10–7 cm2 s−1 reported for Ni(OH)2/graphene nanosheets. Thanks to these unique features high charge/discharge rates can be supported. iii) the in situ electrochemical oxidation process allows a good contact between Ni(OH)2 shell and Ni cores. As a consequence, Ni(OH)2 can easily relax volume change during charge/discharge cycles, showing a good stability.

Table 2 compares the energy storage performances of recent Ni-based nanostructured electrodes. Excellent capacity retention at high charge-discharge rate is required for the development of commercial high power devices. From Table 2 it can be seen that even at high charge-discharge current density our Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains shows higher specific capacity than most of the previous reports11,15,30,31,32,33. A few reports present comparable specific capacity values, however they were recorded at lower current density18,34. Su et al. reported a similar Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell obtained electrode with a higher specific capacity but lower rate capability19, while Jiang and co-workers obtained a specific capacity higher than Ni(OH)2 theoretical limit by using a NiMoO4@Ni(OH)2 core-shell electrode where both core and shell are active materials35. The good cycling stability of the Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains can be further improved by using graphene nanosheets15 or carbon nanotubes31.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we reported a novel Ni(OH)@Ni core-shell nanochains with promising high-rate energy storage performances. The core-shell structure consists of a 3D nanostructured Ni core embedded in a thin Ni(OH)2 shell. The Ni core is formed by interconnected chains-like clusters of Ni nanoparticles (20–30 nm), grown by a low-cost CBD of Ni(OH)2 nanowalls and a low-temperature annealing process. The Ni(OH)2 shell is made of nanocrystalline grains (3–4 nm), obtained by the in situ electrochemical oxidation of the Ni film surface. The electrochemical behaviour of the sample is dominated by faradaic redox processes (battery-like signature), which enabled a high capacity of 237 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1, a high rate capability (76% at 16 A g−1, 32% at 64 A g−1), and good stability (83% capacity retention after 1000 cycles at 16 A g−1). These remarkable features if compared with those of similar NiO and Ni(OH)2-based nanostructures are attributed to the high surface area, faster electron transport, enhanced electric field and improved utilization of the active material provided by the core-shell design. As a result, Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains has potential in many applications, including hybrid supercapacitors, batteries, electrochemical (bio)sensing, gas sensing and photocatalysis. Finally, the reported low-cost preparation of core-shell nanostructures can be used to improve the electrochemical performances of other existing NiO and Ni(OH)2-based electrodes.

References

Zhang, S. & Pan, N. Supercapacitors. Performance Evaluation. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1–19 (2015).

Simon, P. & Gogotsi, Y. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 7, 845–854 (2008).

Zuo, W. et al. Battery-Supercapacitor Hybrid Devices: Recent Progress and Future. Prospects. Adv. Sci. 4, 1–21 (2017).

Brisse, A. L., Stevens, P., Toussaint, G., Crosnier, O. & Brousse, T. Ni(OH)2 and NiO Based Composites: Battery Type Electrode Materials for Hybrid Supercapacitor Devices. Materials. 11, 1178, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11071178 (2018).

Simon, P., Gogotsi, Y. & Dunn, B. Where Do Batteries End and Supercapacitors Begin? Science. 343, 1210–1211 (2014).

Brousse, T., Belanger, D. & Long, J. W. To Be or Not To Be Pseudocapacitive? J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, A5185–A5189 (2015).

Alhebshi, N. A., Rakhi, R. B. & Alshareef, H. N. Conformal coating of Ni(OH)2 nanoflakes on carbon fibers by chemical bath deposition for efficient supercapacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 14897–14903 (2013).

Liu, Y., Wang, R. & Yan, X. Synergistic Effect between Ultra-Small Nickel Hydroxide Nanoparticles and Reduced Graphene Oxide Sheets for the Application in High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitor. Sci. Rep. 5, 11095, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11095 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Ultra-long life nickel nanowires@nickel-cobalt hydroxide nanoarrays composite pseudocapacitive electrode: Construction and activation mechanism. Electrochim. Acta 259, 303–312 (2018).

Li, Z., Zhang, W., Liu, Y., Guo, J. & Yang, B. 2D Nickel Oxide Nanosheets with Highly Porous Structure for High Performance Capacitive Energy Storage. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 51, 045302 (2018).

Parveen, N. & Cho, M. H. Self-Assembled 3D Flower-like Nickel Hydroxide Nanostructures and Their Supercapacitor Applications. Sci. Rep. 6, 27318, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27318 (2016).

Lu, Z., Chang, Z., Zhu, W. & Sun, X. Beta-phased Ni(OH)2 nanowall film with reversible capacitance higher than theoretical Faradic capacitance. Chem. Commun. 47, 9651–9653 (2011).

Sk, M. M., Yue, C. Y., Ghosh, K. & Jena, R. K. Review on advances in porous nanostructured nickel oxides and their composite electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 308, 121–140 (2016).

Dai, X. et al. Ni(OH)2/NiO/Ni composite nanotube arrays for high-performance supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 154, 128–135 (2015).

Wang, K., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Chen, D. & Lin, Q. A novel Ni(OH)2/graphene nanosheets electrode with high capacitance and excellent cycling stability for pseudocapacitors. J. Power Sources 333, 156–163 (2016).

Jiang, W. et al. Nickel hydroxide-carbon nanotube nanocomposites as supercapacitor electrodes: crystallinity dependent performances. Nanotechnology 26, 314003 (2015).

Kang, K. N. et al. Ultrathin nickel hydroxide on carbon coated 3D-porous copper structures for high performance supercapacitors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 719–727 (2018).

Ke, Q. et al. 3D TiO2@Ni(OH)2 Core-shell Arrays with Tunable Nanostructure for Hybrid Supercapacitor Application. Sci. Rep. 5, 13940, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13940 (2015).

Su, Y. Z., Xiao, K., Li, N., Liu, Z. Q. & Qiao, S. Z. Amorphous Ni(OH)2@ three-dimensional Ni core-shell nanostructures for high capacitance pseudocapacitors and asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 13845–13853 (2014).

Li, Q., Liang, C. L., Lu, X. F., Tong, Y. X. & Li, G. R. Ni@NiO core-shell nanoparticle tube arrays with enhanced supercapacitor performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 6432–6439 (2015).

Urso, M. et al. Enhanced sensitivity in non-enzymatic glucose detection by improved growth kinetics of Ni-based nanostructures. Nanotechnology 29, 165601 (2018).

Iwu, K. O., Lombardo, A., Sanz, R., Scirè, S. & Mirabella, S. Facile synthesis of Ni nanofoam for flexible and low-cost non-enzymatic glucose sensing. Sensors Actuators, B Chem. 224, 764–771 (2016).

Medway, S. L., Lucas, C. A., Kowal, A., Nichols, R. J. & Johnson, D. In situ studies of the oxidation of nickel electrodes in alkaline solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 587, 172–181 (2006).

Yuan, Y. F. et al. Nickel foam-supported porous Ni(OH)2/NiOOH composite film as advanced pseudocapacitor material. Electrochim. Acta 56, 2627–2632 (2011).

Ede, S. R., Anantharaj, S., Kumaran, K. T., Mishra, S. & Kundu, S. One step synthesis of Ni/Ni(OH)2 nano sheets (NSs) and their application in asymmetric supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 7, 5898–5911 (2017).

Hu, G., Li, C. & Gong, H. Capacitance decay of nanoporous nickel hydroxide. J. Power Sources 195, 6977–6981 (2010).

Numan, A. et al. Sonochemical synthesis of nanostructured nickel hydroxide as an electrode material for improved electrochemical energy storage application. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 27, 416–423 (2017).

Hall, D. S., Lockwood, D. J., Bock, C. & MacDougall, B. R. Nickel hydroxides and related materials: a review of their structures, synthesis and properties. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 471, 20140792, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2014.0792 (2015).

Young, K.-H. et al. Fabrications of High-Capacity Alpha-Ni(OH)2. Batteries 3, 6, https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries3010006 (2017).

Kim, S. I., Thiyagarajan, P. & Jang, J. H. Great improvement in pseudocapacitor properties of nickel hydroxide via simple gold deposition. Nanoscale 6, 11646–11652 (2014).

Yi, H. et al. Advanced asymmetric supercapacitors based on CNT@Ni(OH)2 core–shell composites and 3D graphene networks. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 19545–19555 (2015).

Gao, L. et al. Flexible Fiber-Shaped Supercapacitor Based on Nickel-Cobalt Double Hydroxide and Pen Ink Electrodes on Metallized Carbon Fiber. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 5409–5418 (2017).

Fu, Y. et al. Hollow mesoporous carbon spheres enwrapped by small-sized and ultrathin nickel hydroxide nanosheets for high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 402, 43–52 (2018).

Xiong, X. et al. Three-dimensional ultrathin Ni(OH)2 nanosheets grown on nickel foam for high-performance supercapacitors. Nano Energy 11, 154–161 (2015).

Jiang, G., Zhang, M., Li, X. & Gao, H. NiMoO4@Ni(OH)2 core/shell nanorods supported on Ni foam for high-performance supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 5, 69365–69370 (2015).

Gilliam, R. J., Graydon, J. W., Kirk, D. W. & Thorpe, S. J. A review of specific conductivities of potassium hydroxide solutions for various concentrations and temperatures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 32, 359–364 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank G. Pantè (IMM-CNR) for technical support. This work was supported by the project “Materiali innovativi e nanostrutturati per microelettronica, energia e sensoristica” - Linea di intervento 2 (Univ. Catania, DFA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.U., S.M. and F.P. conceived the project. M.U. performed samples fabrication and characterization, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. G.T. carried out the simulation. S.B. and C.B. conducted TEM measurements. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Urso, M., Torrisi, G., Boninelli, S. et al. Ni(OH)2@Ni core-shell nanochains as low-cost high-rate performance electrode for energy storage applications. Sci Rep 9, 7736 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44285-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44285-1

This article is cited by

-

Novel mixed heterovalent (Mo/Co)Ox-zerovalent Cu system as bi-functional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Enlightening the bimetallic effect of Au@Pd nanoparticles on Ni oxide nanostructures with enhanced catalytic activity

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

A novel and ultrasensitive non-enzymatic electrochemical glucose sensor in real human blood samples based on facile one-step electrochemical synthesis of nickel hydroxides nanoparticles onto a three-dimensional Inconel 625 foam

Journal of Applied Electrochemistry (2023)

-

Trapping and detecting nanoplastics by MXene-derived oxide microrobots

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Electrospun Ni-Ni(OH)2/Carbon Nanofibers as Flexible Binder-Free Supercapacitor Electrode with Enhanced Specific Capacitance

Journal of Electronic Materials (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.