Abstract

The association of overall diet quality based on the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top with risk of depression is not known. This prospective cohort study aimed to determine whether higher adherence to the Japanese food guide reduced the risk of depression. Of 12,219 residents enrolled at baseline, we extracted 1,112 participants who completed a 5-year follow-up (1995) and participated in a mental health screening (2014–2015). Diet quality was scored based on adherence to the Japanese food guide and the ratio of white to red meat according to the Alternative Healthy Index and ranged from 0 (worst) to 80 (best). We calculated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for current psychiatrist-diagnosed depression per quartile of total score and of eight component scores with the lowest quartile as reference. Mean age of the participants was 73 years and 59% were women. Total diet quality score was not significantly associated with risk of depression 20 years after the baseline assessment. Among the eight components on the diet quality score, there was a significantly reduced risk for the highest quartile of the white to red meat ratio score. In conclusion, our results do not indicate that higher adherence to the Japanese food guide prevents depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extensive research indicates that diet is one of the biggest risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs)1,2,3,4,5. Therefore, for prevention of NCDs, several countries have introduced their own dietary recommendations or guidelines that consider their population’s eating habits. In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries jointly developed the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top to emphasize the optimal balance and quantity of food in the daily Japanese diet. In 2016, Kurotani et al.6 found that a higher overall diet quality score was associated with a lower risk of mortality via a large-scale prospective cohort study (N = 79,594) assessing diet quality based on adherence to the Japanese food guide in 11 Japanese regions. For the influence of diet on depression, several mechanisms have been proposed based on animal studies and observational studies in humans, such as the gut microbiota7, inflammatory signaling8, and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis9,10. However, the association between diet quality and depression has remained unclear.

A recent cross-sectional study reported that a higher overall quality score based on adherence to the Japanese food guide was associated with lower risk of self-reported depressive symptoms in young and middle-aged women11. Although a recent meta-analysis of 24 independent cohorts (totaling 1,959,217 person-years) also reported that higher diet quality, regardless of type, was associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms12, there was no effect of diet quality on depression in studies using a formal diagnosis as an outcome12,13,14,15 or when there was a control for depressive symptoms at baseline12. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no prospective study has examined the influence of diet quality on the risk of depression formally diagnosed by a psychiatrist.

In addition, the meta-analysis also reported the association of healthy and unhealthy food groups with the risk of depressive symptoms12, with significant risk reductions found for fish and vegetables. However, no study has examined the association of adherence to food groups with the risk of psychiatrist-diagnosed depression. The Japanese food guide makes recommendations on seven components: grain dishes, vegetable dishes, fish and meat dishes, milk, fruits, total energy, and snacks and alcoholic beverages. However, the Japanese food guide takes into account the total amount of fish and meat dishes but does not distinguish between the two. While higher meat consumption may increase the incidence of depression16, higher fish consumption may reduce its incidence12. Thus, to assess diet quality and consider the contents of fish and meat dishes in reference to the Alternate Healthy Eating Index6,17, we added the ratio of white to red meat to the seven components of the Japanese food guide.

Thus, this prospective population-based cohort study examined whether higher adherence to the Japanese food guide reduces the risk of psychiatrist-diagnosed depression. In addition, we explored the association of adherence to the recommendations for eight components—grain dishes, vegetable dishes, fish and meat dishes, milk, fruits, total energy, snacks and alcoholic beverages, and the ratio of white to red meat—with risk of depression.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This study was conducted in one region of the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study (JPHC study), which was started in 199018. A self-administered questionnaire on demographic characteristics, past medical history, and lifestyle-related factors was distributed at baseline and at 5- and 10-year follow-ups. The flow diagram of study participants is shown in Fig. 1. Among 12,219 residents aged 40–59 years at baseline in the Saku Public Health Center catchment area in Nagano prefecture, 8,827 participants were invited to a mental health screening (2014–2015) after the exclusion of 3,392 participants who moved out of the study area, died, or did not respond to questionnaires during follow-up (1990–2014). Of the 1,299 participants who participated in the mental health screening (2014–2015), 1,185 participants completed the 5-year follow-up questionnaires (1995). Participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study. We ultimately analyzed 1,112 participants (460 men and 652 women) after excluding 73 participants who reported consumption in the upper 1% of each category (grain dishes, vegetable dishes, fish and meat dishes, milk, fruits, and energy from snacks and alcohol) or in either the upper or lower 1% of the range of energy intakes. The institutional review board at the National Cancer Center Japan and Keio University School of Medicine approved all procedures. We wrote our research protocol based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement19 and conducted our research by adhering to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki20.

Dietary assessment

We used a food frequency questionnaire at the 5-year follow-up survey (1995) to collect data on 147 food items21. Regarding the consumption frequency of each food item, participants chose from nine options ranging from never to seven or more times a day. Participants also classified the standard portion sizes for each food item as small (50% less than standard), medium (same as standard), and large (50% more than standard). We calculated the daily food intake by multiplying the consumption frequency by the standard portion size for each food item and assessed the daily intake of energy and nutrients using the Japanese Standard Tables of Food Composition. A previous study22 demonstrated the validity of the food frequency questionnaire by calculating the Spearman rank correlation coefficients between the energy-adjusted intakes determined using the food frequency questionnaire and the intakes determined using 14- or 28-day diet records. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.13 for sake to 0.75 for coffee in men and from 0.12 for shochu to 0.80 for coffee in women. Regarding test-retest reproducibility, the study also calculated the Spearman rank correlation coefficients between the energy-adjusted intakes using two food frequency questionnaires administered at a 12-month interval. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.21 for wine to 0.79 for rice in men and from 0.37 for sake to 0.80 for coffee in women.

To assess diet quality, we calculated the diet quality score as described previously6 and as shown in Supplementary Table S1. The diet quality score assessed the degree of adherence to the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top, which is a practical and concrete food guide based on dietary guidelines for the Japanese population and was developed with the aim of preventing NCDs in the Japanese population in consideration of Japanese dietary habits. This diet quality score, defined as a modified score in the previous study6, has eight components—grain dishes, vegetable dishes, fish and meat dishes, milk, fruits, total energy, snacks and alcoholic beverages, and ratio of white to red meat—, with a score of 10 allocated to those who consumed the recommended amount of each component. The ratio of white to red meat was added to the original diet quality score in reference to the Alternate Healthy Eating Index6,17. The recommended amount of each component was specified by sex, age, and level of physical activity based on the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top (Supplementary Table S1). When a participant exceeded or fell short of the recommended amount of each component, the score was allocated proportionately between 0 and 10 based on the degree of adherence to the recommended amount. Finally, each score was rounded off to the nearest whole number. All component scores were summed to give the total score, which ranged from 0 (lowest adherence) to 80 (highest adherence).

Follow-up and outcome

We followed up the participants annually and determined any changes in participants using the residential registry in the Saku area until the present screening in 2014 and 2015. We identified cancer incidence using data from the major hospital in this area. Because we identified the incidence of stroke and myocardial infarction from the data of this hospital in 2009, we identified past history of depression, diabetes mellitus, stroke, and myocardial infarction by questionnaire in the present screening. Certified psychiatrists diagnosed depression based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria in reference to the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)23,24 and the Center for Epidemiological Scale-Depression (CES-D)25,26, which had been distributed beforehand, as described elsewhere27.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for current depression diagnosis per quartile of the total score and of each component score on the Japanese food guide with the lowest quartile as reference. We used two models to estimate the ORs and 95% CIs. The first model was adjusted for age (years, continuous) and sex. The second model was further adjusted for living alone (yes or no), education (primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education, post-secondary education), smoking status (never, former, current), alcohol frequency (almost never, 1–3 times per month, ≥1 times per week), physical activity (metabolic equivalent task h/day, continuous), past history of depression (yes or no), cancer (yes or no), stroke (yes or no), myocardial infraction (yes or no), and diabetes mellitus (yes or no). We evaluated the linear trend by treating the quartile of the total score and each component score on the Japanese food guide as a continuous variable. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Center Japan.

Results

Mean age of the 1,112 participants included in the final analysis was 73 years and 59% were women. Median total score on the Japanese food guide was 58 (range, 25 to 80) points. As shown in Table 1, significant differences were found in sex, history of cancer and stroke, current smoking, and regular drinking between individuals with lower scores (lower quality diet) and individuals with higher scores (high quality diet). Participants with a higher quality diet tended to be female, without history of cancer and stroke, and without smoking and drinking habits. Of the 1,112 participants, 85 (7.6%) were diagnosed with depression, with mean scores of 19.3 (standard deviation = 4.5) for the CES-D and 7.1 (standard deviation = 3.3) for the PHQ-9.

The influence of adherence to the Japanese food guide on depression risk is shown in Table 2. According to the total score on the Japanese food guide, there was no significant association with depression in the highest quartile for the total score (OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.58–2.63), rather also after adjustment for possible confounding factors. Although we conducted sensitivity analyses of the participants according to sex, history of depression, history of illness, current smoking, regular drinking habits, living alone, education, and physical activity, there was no significant association with depression (Table 2).

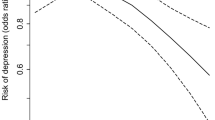

Among the eight components on the food quality score, there was a significantly reduced depression risk for the highest quartile of the white to red meat ratio score (OR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.27–0.98) and a significant linear trend (p < 0.05) after adjustment for possible confounding factors (Supplementary Table S2). There were no significant associations of the scores with grain dishes, vegetable dishes, fish and meat dishes, milk, fruits, total energy, and snacks and alcoholic beverages with depression.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the influence of adherence to the Japanese food guide on the risk of depression. Our results showed that a higher total diet quality score (higher quality diet) was not significantly associated with a lower risk of depression. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to examine the association of quality of diet based on adherence to the Japanese food guide with risk of psychiatrist-diagnosed depression. Our findings also suggest that a higher ratio of white to red meat could be associated with lower risk of depression.

Rather also after adjustment for possible confounding variables, a higher total score (higher quality diet) was not significantly associated with a lower risk of psychiatrist-diagnosed depression. This result is in line with the conclusion of a recent meta-analysis that reported that the associations determined for higher diet quality differed between the risk of depressive symptoms (OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.69–0.84) and the risk of formally diagnosed depression (OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.68–1.23)12. This difference could be explained by the beneficial effects of a higher diet quality on NCDs. A higher quality diet is associated with a significantly reduced risk of NCDs such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer6,28. Patients with these NCDs tend to have somatic symptoms such as fatigue, loss of appetite, insomnia, and work difficulty in conjunction with depression29,30,31. These somatic symptoms related to NCDs might be present regardless of the lack of core depressive symptoms such as depressed mood and anhedonia, which are required for the diagnosis of depression32. Hence, a self-report questionnaire could overestimate depression among patients with an NCD. Furthermore, a higher quality diet has been associated with a reduced risk of these somatic symptoms among patients with NCDs33,34. Therefore, a higher quality diet might not reduce the risk of a depression diagnosis but might reduce the risk of a higher score on the self-report questionnaire.

In addition, our finding that a higher quality diet was not significantly associated with a lower risk of psychiatrist-diagnosed depression could be related to differences in study design. Among the three studies that used a formal diagnosis as an outcome in the previous meta-analysis of prospective studies12, one study involving male and female university students found a significant relationship of the diets conforming to the Pro-vegetarian Dietary Pattern and the Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 with the incidence of depression (OR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.44–0.77) in a 4-year follow-up13. In contrast, one study of boys and girls aged 10–11 years did not find a significant relationship between diet quality (evaluated using the Diet Quality Index-International) and the incidence of internalizing disorder including depressive and anxiety symptoms (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.73–1.63) in a 4-year follow-up15. Finally, one study involving middle-aged and older women did not find a significant relationship between prudent dietary patterns (high in vegetables, fruit, whole grain, and fish) and the incidence of depression (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.91–1.20) in a 12-year follow-up14, which is in line with our findings for older men and women in a 19-year follow-up. These inconsistent results could be attributable to differences in the age of the study population, dietary assessment, and follow-up period. Further studies are necessary to examine the influence of diet quality on formally diagnosed depression and to consider differences in the age of the study population, diet assessment, and follow-up period.

A recent meta-analysis including 16 randomized controlled trials found positive effects of dietary improvement on depressive symptoms (Hedges g = 0.275, 95%CI = 0.10–0.45 for the overall effect size of dietary interventions)35. However, some researchers have questioned the remarkably large effect of one of the trials. Regarding the SMILES study36, Molendijk et al.37 have noted the possibility that selectively induced expectancy and loss of blinding may have led to the large effect (d = 1.98 for the pre–post effect). Including our results showing no association between diet quality and psychiatrist-diagnosed depression, the evidence regarding the association of diet with depression is inconsistent. Therefore, to develop effective nutritional prevention of depression, it is necessary to further examine the association between diet and depression.

Our results also indicate that a higher ratio of white to red meat could be associated with a dose-dependent lower risk of depression. Compared with participants in the lowest quartile, who had an approximately equal ratio of white to red meat, the participants in the highest quartile, who had an approximately 4:1 ratio of white to red meat, had greater than a 40% reduced risk of depression. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show a relationship between the ratio of white to red meat and depression. The participants in this study consumed 90% of white meat from fish (data not shown). Our previous study has shown the beneficial effects of fish consumption on depression27. Thus, we assumed that fish consumption influenced our current findings on the relationship between the ratio of white to red meat and depression. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of three cohort studies showed that higher meat consumption was associated with a higher incidence of depression (relative risk = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.03–1.24)16. These previous studies indicated that depression could be affected by the balance between the consumption of white meat, including fish, and red meat. The balance between the consumption of white meat and red meat could be an additional component of the Japanese food guide and its effects on depression should be examined in further prospective studies.

Although the strengths of this study are its prospective design, controls for possible confounding, and the psychiatrist-certified diagnosis of depression, we need to mention several limitations. First, because it was necessary for the participants in this study to come to a specific place on a specific day when the certified psychiatrist was available, only 14% of the residents enrolled at baseline (1990) participated in this study (2014–2015). Their participation could also be based on their health-related preferences or motivations, and thus might cause selection bias. Second, we unfortunately did not have baseline information on depression. The aforementioned systematic review12 reported that there is no effect of diet quality on depression when there is a statistical control for baseline depressive symptoms. Further studies should examine the influence of diet quality on psychiatrist-diagnosed depression after excluding the influence of baseline depressive symptoms. Third, we calculated diet quality at only a 5-year follow-up survey and did not assess any further changes in diet. Thus, the quality of the diet might not reflect habitual diet quality beyond the 5-year follow-up survey. However, a cohort study assessing changes in dietary patterns among older adults showed that approximately 60% of participants had a stable dietary pattern during a 10-year follow-up38. Therefore, we considered the diet quality at the 5-year follow-up survey to represent habitual diet quality after the 5-year follow-up survey. Finally, we did not assess depression during the follow-up period and conducted the psychiatric interview once 25 years after the baseline assessment. Although certified psychiatrists diagnosed depression based on DSM-IV criteria in reference to the PHQ-9 and CES-D, we did not use a structured clinical interview for the psychiatric diagnosis.

In conclusion, our results do not indicate that higher adherence to the Japanese food guide prevents psychiatrist-diagnosed depression. Further studies are necessary to examine the influence of diet quality on psychiatrist-diagnosed depression and to consider differences in the age of the study population, diet assessment, and follow-up period.

References

Murray, C. J. et al. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. Jama 310, 591–608, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.13805 (2013).

Okubo, R., Chen, C., Sekiguchi, M., Hamazaki, K. & Matsuoka, Y. J. Mechanisms underlying the effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on fear memory processing and their hypothetical effects on fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids 131, 14–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2018.03.006 (2018).

Holt, R. I. The prevention of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in people with schizophrenia. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica 132, 86–96, https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12443 (2015).

Hayward, J. et al. Lifestyle factors and adolescent depressive symptomatology: Associations and effect sizes of diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry 50, 1064–1073, https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867416671596 (2016).

Jacka, F. N. et al. Associations between diet quality and depressed mood in adolescents: results from the Australian Healthy Neighbourhoods Study. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry 44, 435–442, https://doi.org/10.3109/00048670903571598 (2010).

Kurotani, K. et al. Quality of diet and mortality among Japanese men and women: Japan Public Health Center based prospective study. Bmj 352, i1209, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1209 (2016).

Okubo, R. et al. Effect of Bifidobacterium breve A-1 on anxiety and depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: A proof-of-concept study. Journal of affective disorders 245, 377–385, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.011 (2019).

Su, K. P., Matsuoka, Y. & Pae, C. U. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Prevention of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Clinical psychopharmacology and neuroscience: the official scientific journal of the Korean College of Neuropsychopharmacology 13, 129–137, https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2015.13.2.129 (2015).

de Kloet, E. R. & Molendijk, M. L. Coping with the Forced Swim Stressor: Towards Understanding an Adaptive Mechanism. Neural plasticity 2016, 6503162, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6503162 (2016).

Molendijk, M. L. & de Kloet, E. R. Immobility in the forced swim test is adaptive and does not reflect depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 62, 389–391, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.08.028 (2015).

Sakai, H. et al. Food-based diet quality score in relation to depressive symptoms in young and middle-aged Japanese women. The British journal of nutrition 117, 1674–1681, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114517001581 (2017).

Molendijk, M., Molero, P., Ortuno Sanchez-Pedreno, F., Van der Does, W. & Angel Martinez-Gonzalez, M. Diet quality and depression risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Journal of affective disorders 226, 346–354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.022 (2018).

Sanchez-Villegas, A. et al. A longitudinal analysis of diet quality scores and the risk of incident depression in the SUN Project. BMC medicine 13, 197, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0428-y (2015).

Chocano-Bedoya, P. O. et al. Prospective study on long-term dietary patterns and incident depression in middle-aged and older women. The American journal of clinical nutrition 98, 813–820, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.052761 (2013).

McMartin, S. E., Kuhle, S., Colman, I., Kirk, S. F. & Veugelers, P. J. Diet quality and mental health in subsequent years among Canadian youth. Public health nutrition 15, 2253–2258, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012000535 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Is meat consumption associated with depression? A meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC psychiatry 17, 409, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1540-7 (2017).

McCullough, M. L. et al. Diet quality and major chronic disease risk in men and women: moving toward improved dietary guidance. The American journal of clinical nutrition 76, 1261–1271, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1261 (2002).

Tsugane, S. & Sawada, N. The JPHC study: design and some findings on the typical Japanese diet. Japanese journal of clinical oncology 44, 777–782, https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyu096 (2014).

von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X (2007).

General Assembly of the World Medical, A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. The Journal of the American College of Dentists 81, 14–18 (2014).

Sasaki, S., Kobayashi, M., Ishihara, J. & Tsugane, S. & Jphc. Self-administered food frequency questionnaire used in the 5-year follow-up survey of the JPHC Study: questionnaire structure, computation algorithms, and area-based mean intake. Journal of epidemiology 13, S13–22 (2003).

Nanri, A. et al. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed by a food frequency questionnaire used in the 5-year follow-up survey of the Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. Journal of epidemiology 22, 205–215 (2012).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine 16, 606–613 (2001).

Muramatsu, K. et al. The patient health questionnaire, Japanese version: validity according to the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview-plus. Psychological reports 101, 952–960, https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.101.3.952-960 (2007).

Radloff, L. S. The CES-D Scale: a Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1, 385–401 (1997).

Shima, S., Shikano, T., Kitamura, T. & Asai, M. A new self-report depression scale (in Japanese). Seishinigaku 27, 717–723 (1985).

Matsuoka, Y. J. et al. Dietary fish, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid consumption, and depression risk in Japan: a population-based prospective cohort study. Translational psychiatry 7, e1242, https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.206 (2017).

Schwingshackl, L., Bogensberger, B. & Hoffmann, G. Diet Quality as Assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 118, 74–100 e111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.08.024 (2018).

Akechi, T. et al. Symptom indicator of severity of depression in cancer patients: a comparison of the DSM-IV criteria with alternative diagnostic criteria. General hospital psychiatry 31, 225–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.12.004 (2009).

Sartorius, N. Depression and diabetes. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience 20, 47–52 (2018).

Lyketsos, C. G. et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. Jama 288, 1475–1483 (2002).

de Jonge, P. et al. Symptom dimensions of depression following myocardial infarction and their relationship with somatic health status and cardiovascular prognosis. The American journal of psychiatry 163, 138–144, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.138 (2006).

George, S. M. et al. Better postdiagnosis diet quality is associated with less cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Journal of cancer survivorship: research and practice 8, 680–687, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0381-3 (2014).

Fitzgerald, K. C. et al. Diet quality is associated with disability and symptom severity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 90, e1–e11, https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004768 (2018).

Firth, J. et al. The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosomatic medicine, https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000673 (2019).

Jacka, F. N. et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC medicine 15, 23, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y (2017).

Molendijk, M. L., Fried, E. I. & Van der Does, W. The SMILES trial: do undisclosed recruitment practices explain the remarkably large effect? BMC medicine 16, 243, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1221-5 (2018).

Harrington, J. M., Dahly, D. L., Fitzgerald, A. P., Gilthorpe, M. S. & Perry, I. J. Capturing changes in dietary patterns among older adults: a latent class analysis of an ageing Irish cohort. Public health nutrition 17, 2674–2686, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014000111 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank all staff members in the Saku area for their extensive efforts to conduct the survey. The cohort study was originally supported by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (since 2011) and a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour, a grant from SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation, and Welfare of Japan (from 1989 to 2010). This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 17H04253). The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; data collection; data management; analysis; interpretation of the data; review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Drs. Okubo, Matsuoka, Sawada, and Mimura significantly contributed to making the protocol of this study. Drs. Sawada, Mimura, Nozaki, Shikimoto, and Tsugane, significantly contributed to the data collection. Drs. Okubo, Matsuoka, Sawada, Mimura, Kurotani, and Tsugane significantly contributed to the interpretation of our data and writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The Division of Health Care Research, Center for Public Health Sciences, National Cancer Center Japan (Chief: Dr. Matsuoka) has received a donation from Morinaga Milk Industry Co. Ltd. Dr. Matsuoka has received speaker’s honoraria from Morinaga Milk Industry, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Mochida Pharmaceutical, and NTT data. Dr. Mimura has received grants and/or speaker’s honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Fuji Film RI Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Mochida Pharmaceutical, MSD, Nippon Chemipher, Novartis Pharma, Ono Yakuhin, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Takeda Yakuhin, Tsumura, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin within the past 3 years. Other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okubo, R., Matsuoka, Y.J., Sawada, N. et al. Diet quality and depression risk in a Japanese population: the Japan Public Health Center (JPHC)-based Prospective Study. Sci Rep 9, 7150 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43085-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43085-x

This article is cited by

-

The association between midlife living arrangement and psychiatrist-diagnosed depression in later life: who among your family members reduces the risk of depression?

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Associations between diet quality and DSM-IV mood disorders during young- to mid-adulthood among an Australian cohort

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.