Abstract

In 2017, three major hurricanes (Irma, Jose, and Maria) impacted the Northeastern Caribbean within a 2-week span. Hurricane waves can cause physical damage to coastal ecosystems, re-suspend and transport antecedent seafloor sediment, while the associated intense rainfall can yield large influxes of land-derived sediment to the coast (e.g. burial of ecosystems). To understand sedimentation provenance (terrestrial or marine) and changes induced by the hurricanes, we collected bathymetry surveys and sediment samples of Coral Bay, St. John, US Virgin Islands in August 2017, (pre-storms) and repeated it in November 2017 (post-storms). Comparison reveals morphologic seafloor changes and widespread aggradation with an average of ~25 cm of sediment deposited over a 1.28 km2 benthic zone. Despite an annual amount of precipitation between surveys, sediment yield modeling suggests watersheds contributed <0.2% of the total depositional volume. Considering locally established accumulation rates, this multi-hurricane event equates to ~1–3 centuries of deposition. Critical benthic communities (corals, seagrasses) can be partially or fully buried by deposits of this thickness and previous studies demonstrate that prolonged burial of similar organisms often leads to mortality. This study illuminates how storm events can result in major sediment deposition, which can significantly impact seafloor morphology and composition and benthic ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical cyclones are among the most destructive natural hazards on Earth1. Approximately 133 tropical cyclones form annually in the world’s oceans (86 tropical storms and 47 hurricanes, on average over the past 30 years)2. Of those, approximately half impact Southeast Asia (37%) and the Caribbean (14%)2. Both of these regions are composed primarily of open water with many small tropical islands with infrastructures easily damaged and/or destroyed by tropical cyclones3. Tropical islands have been developing rapidly for decades due to growing populations and economies4. The land-use changes that accompany population growth often enhance land-derived sedimentation, which can negatively affect coral reefs and other nearshore ecosystems5,6 (Fig. 1). Large waves from storms can also transport marine-derived sediment onshore and into the coastal zone7 (Fig. 1). The degradation of coastal ecosystems, exacerbated by sedimentation among other stressors8, threatens ecosystems, reef fish populations, and consequently the economies of tropical nations9,10,11,12.

Coastal ecosystems are critical to economic, cultural, and ecologic health12,13,14, yet are vulnerable to hurricanes15. For example, calcareous algae are reef builders16, seagrasses serve as fish nurseries17,18, and coral reef communities create diverse habitats14 and buffer the coast from wave action and storms19. Coastal vegetation such as seagrass communities are an important source for carbon capture and storage and do so ~2x more efficiently than tropical rainforests20. Coastal marine communities are resilient to small storm events21,22 in which the circulation of water and sediment can actually stimulate diversity8, cover23 and new growth24 while having little positive or negative effect on other communities25. Conversely, large storm events can result in full mortality due to burial of most coral species5,26, some calcareous algaes27 and some tropical seagrasses28,29,30,31 (exacerbated by accompanying salinity decreases32). If uncovered rapidly enough, seagrasses31,33, calcareous algaes25 and some corals8,34,35 are able to partially recover. Additionally, breakage and fragmentation accompanying burial during hurricanes is not necessarily lethal for some coral communities35,36 and fragmentation can be inconsistent and patchy37. Broken calcareous algae plates are often found following large storms38 (including in this study) despite their resilience and common recovery25. Specifically in the Caribbean, hurricanes have led to dramatic declines in dominant coral species39,40,41.

St. John, US Virgin Islands (USVI) is a volcanic island in the Caribbean Leeward Islands (Fig. 2)42. The coastal system has two dominant sources of sediment: marine-derived carbonates and terrigenous-derived volcaniclastics43,44. The steep slopes, short pathways to the coast, and weathered volcanic soils of the island make it particularly susceptible to land-based sediment erosion and coastal deposition from both human and natural causes45,46,47 (Fig. 1). There are no perennial rivers on St. John, only a series of ephemeral gullies activated by extreme rainfall events48,49,50,51. This allows a situation in which the land-based sediment transport system is either turned ‘on’ (during rainfall events) or ‘off’ (Fig. 1). These characteristics create an easily distinguishable terrestrial vs. marine signal in the geologic record following any erosional and depositional event (Fig. 1).

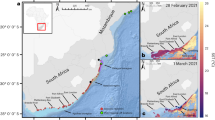

Bottom Left: Eastern Puerto Rico and the US and British Virgin Islands with the 2017 hurricane tracks from Category 5 Hurricanes Irma and Maria52,55. St. John, US Virgin Islands sits on a shelf ~60 meters below sea level (This map was generated using NOAA’s U.S. Virgin Islands 1 arc-second MHW Coastal Digital Elevation Model96 with ESRI ArcGIS 10.6, www.esri.com). Top Left: St. John, US Virgin Islands showing the watershed source area (This map and the map shown to the right were generated using US Army Corps of Engineers US Virgin Islands Orthophoto Mosaic97 using ESRI ArcGIS 10.6, www.esri.com). Right: Coral Bay, St. John with its protected waters and lands. Bathymetry shown was collected after the 2017 hurricane season in November and December of 2017.

The year 2017 was historic, as numerous major hurricanes severely impacted many Caribbean Islands and portions of the continental United States. Hurricane Irma was one of the longest and most intense hurricanes on record and the strongest storm (maximum sustained wind speed = 83 m s−1) to make landfall in the Leeward Islands52,53. In terms of accumulated cyclone energy, Hurricane Irma alone equaled an entire average Atlantic hurricane season52. Irma made landfall at near peak intensity on Virgin Gorda, British Virgin Islands on September 6th, 2017, ~36 km northeast of Coral Bay, St. John, USVI52 (Fig. 2, Table 1). As the storm moved in the west-north-west direction, the eyewall passed over Coral Bay. The eyewall of the hurricane often has the greatest wind speed and heaviest rainfall of the storm cell2 (Table 1). Thus, Irma resulted in widespread damage throughout St. John.

On September 10th, 2017, four days after Hurricane Irma hit St. John, Category 4 Hurricane Jose passed ~215 km northeast of the island54, though little rains, waves, or winds affected St. John (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). Eight days later on September 20th, 2017, the eye of Category 5 Hurricane Maria passed ~90 km south of St. John, just 14 days after Hurricane Irma55 (Fig. 2). As Maria moved past St. John it reached its peak intensity of 77 m s−1 (Table 1)55. A buoy located ~11 km southwest of Coral Bay recorded maximum wave heights of 5.6 and 7.9 meters with maximum periods of 10.5 and 11.8 seconds for Irma and Maria, respectively56 (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). Coral Bay opens to the Caribbean Sea in an east-south-east direction (Fig. 2). Thus, Coral Bay’s orientation is exposed to a direct impact from common Atlantic hurricane trajectories. Wave heights and periods during Jose were near average and likely did not affect the region due to low wave height56 (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S1).

Understanding modern hurricane deposition is important for assessing impacts to coastal ecosystems and to accurately interpret the geologic record of past events. Furthermore, characterizing previous storm events is challenged by the difficulty in distinguishing a storm bed from a tsunami bed and vice versa57,58, despite excellent modern stratigraphic records48,59. In this study, we use a rare dataset to map and characterize the deposition that occurred following three major 2017 hurricanes (Irma, Jose, and Maria). We acquired multibeam bathymetry and sediment grab and core samples in Coral Bay shortly before and after the three storms. Modern multibeam bathymetry is particularly adept at resolving fine-scale differences in the nearshore environment, where techniques such as LiDAR are inadequate due to nearshore water turbidity60. Sediment samples provided crucial ground-truthing for pre- and post-storm multibeam surveys. This pre- vs. post-storm comparison is the first, to our best knowledge, to be collected in a tropical island setting. Our objectives are to use this rare dataset to map modern hurricane deposition and erosional patterns to better understand historical hurricane records, future depositional units and their potential impacts on the coastal system (Fig. 1).

Results

Pre/Post Storm Survey Difference Map

The post-storm minus pre-storm multibeam bathymetry difference map (Fig. 3) shows widespread deposition throughout the 1.28 km2 coverage area. The depositional layer is fairly uniform (~+/−20 cm) in distribution, except an area of thick accumulation (+40–62 cm) in southwestern Coral Harbor and northwestern Sanders Bay (Fig. 3). Despite deposition throughout most of the survey area, some erosion occurred, especially around the perimeters of coral mounds (1–3 m in height) in the southern part of the survey area (Fig. 3). In particular, the mounds displayed a flute mark pattern of deposition toward Coral Harbor and erosion seaward (Fig. 3). The total calculated depositional volume is +322,317 m3 and the erosional volume is −29,329 m3 using the average determined vertical offset and a 10 cm grid spacing (Methods). If distributed evenly over the coverage area, the average thickness of the depositional unit would be ~25 cm. Considering uncertainties in the vertical offset, the average thickness of the depositional unit is 25 cm +/− 12 cm (Methods).

A difference map of Coral Bay, St. John, USVI. The post-storm November 2017 survey was subtracted from the pre-storm August 2017 survey. Deposition is indicated by positive values (green, yellow, orange, red); erosion in negative values (blue). The largest area of deposition (outlined with a black dashed line) is characterized by deposition ranging from 20 to 60 cm. Coral mounds in central Johnson Bay have a general flute mark pattern of deposition toward Coral Harbor and erosion to seaward. Six sediment cores (white circles) were collected in November of 2017.

Sediment Sample Analysis

7Be (half-life ~53 days) can be used to detect recent terrigenous sediment input (i.e., over the past ~1 year), and was found at 16 of 31 sample locations (cores and grabs) taken post storm (November 2017) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S1). As expected, presence of 7Be was observed near major gully effluences and not in the center of the bay (Fig. 4). One sample in south-central Johnson Bay had 7Be detected, but is proximal to a narrow seafloor channel (Figs 2 and 4). Of these, 7Be was detected in the six sediment cores collected in/near our survey area in November, 2017 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S1). Core 4 (Fig. 3) had 7Be from the core top downcore to ~1 cm. Two cores (2 and 5), detected 7Be down to 0.8 cm, and three cores (3, 7, and 8) detected 7Be down to at least 0.2 cm (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S1). Also present in Core 2 was a capping unit extending ~4 cm downcore dominantly composed of coralline algae (Halimeda spp., indicating that it is primarily marine-derived) and mixed carbonate/terrestrial sands and silts (Figs 3 and 5). The location of Core 2 was previously core sampled in 200261 and shows matching stratigraphy except for the capping 4 cm layer (Fig. 5).

Surficial mineralogy of Coral Bay, St. John pre (left) and post (right) September 2017 Hurricanes Irma, Jose, and Maria. The post hurricane map also includes samples run for 7Be (triangles). Both pre- and post-storms, the seafloor was predominantly carbonate while there was some intrusion of terrestrial material following the hurricanes in northern Coral Harbor (right). Mineralogy was determined by XRD (X-Ray Diffraction).

Core 2 collected in November 2017 (location in Fig. 4) showing a 3–4 cm thick surficial layer visible in the core photo (left) and XCT scan (middle). This layer was not present in a core taken in 2002 in the same location (right). This layer also contains Beryllium-7 indicating recent deposition (~months). X-Ray Computed Tomography (XCT).

The mineralogy of surface sediments both pre- and post-storms is dominated by marine-derived carbonate minerals (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S2). High percentages (>80%) of marine carbonates persist away from the coast in Sanders and Johnson Bay both pre- and post-hurricanes Irma, Jose, and Maria. Isolated spots near the coast (gully effluences) have lower percentages of carbonate minerals (Fig. 4). Carbonate content generally decreased post-storm in the northern and middle parts of the Coral Harbor, but slightly increased in the southern region (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Hurricanes Irma and Maria, and likely to a lesser extent Jose, resulted in a widespread depositional unit throughout western Coral Bay (Fig. 3). This is confirmed independently by pre- and post-storm multibeam bathymetry differencing and sediment sample analysis. The depositional layer varies in thickness, but in general is on the decimeter scale. Decimeter-scale storm beds are consistent with findings from other hurricane studies employing a range of methods62,63,64,65. Rapid-response studies that assess sedimentation and morphologic seafloor changes following major hurricanes are rare and have generally focused on the barrier island systems of the contiguous United States64,66,67. A common finding from pre- and post-storm analyses documents the potential for significant sediment transport and deposition in the marine environment, similar to other rapid and longer term studies focusing on storm deposition in coastal embayments59,65,66. In nearshore regions (1–15 m water depth), net deposition of 10–30 cm has been commonly observed with little erosion7,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,70,71. While erosion has been observed in some offshore settings (>15 m water depth)21,62,63,64,66,72. In a similar island setting to St. John, Kosciuch et al.7 found 10–44 cm thick deposits following Category 5 Tropical Cyclone Pam in embayments in Vanuatu in the southeast Pacific. Overall, our average of 25 cm depositional thickness with little erosion in a nearshore environment (0.5–17.5 m water depth) is consistent with other studies.

We interpret that much of the net sediment volume increase in Coral Bay is due to marine sediment resuspension and transport caused by extreme wave action and strong wind and wave-induced currents. Sediment mobilization is dependent on many factors including: bay-bottom roughness, grain size and density, seawater density, wave height and period, water depth, and orbital velocity at the sea floor73. We modeled wave height and period using the SWAN wave model and estimated orbital velocities using linear wave theory (Methods). We assumed seabed roughness conservatively74 from previously measured45 medium-sized sand grains (0.05 cm diameter), and used the standard specific gravity for aragonite (2.93 g/cm3), which is a common carbonate mineral found in this region43 and in the deposit (Fig. 4, Table 2, and Supplementary Table S2). We combined these parameters with our modeled results to calculate the non-dimensional critical Shields parameter for both Hurricane Irma and Maria (Methods) (Fig. 6). The critical Shields parameter indicates the minimum non-dimensional shear stress needed for sediment mobilization75.

Calculated and modeled products from SWAN wave model in St. John, US Virgin Islands during Hurricane Irma (left) and Maria (right) in 2017. Panel A: Maximum wave height and direction during Hurricane Irma. Vector arrows show dominant wave direction. CARICOOS wave buoy location is noted in Table 1 (listed as “S. of St. John”) and in the text. Panel B: Maximum wave height and direction for Hurricane Maria. Vector arrows show dominant wave direction. Panel C: Maximum Shields parameter for Hurricane Irma. The white line represents the contour for critical Shields parameter (θcrit = 0.032). Panel D: Maximum Shields parameter for Hurricane Maria. The white line represents the contour for critical Shields parameter (θcrit = 0.032). (All image data shown are from Google, Digital Globe and generated using MatLabR2018b, https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html).

Using the parameters mentioned above and standard values for seawater density and viscosity for the region (Table 2), the critical Shields parameter was estimated at 0.032 (Methods)76. Maximum non-dimensional shear stresses (Shields parameter) were then estimated over the southern St. John seafloor (Fig. 6) again using parameters derived in Table 2 and the wave model output (Methods). During both Irma and Maria the critical Shields parameter value was greatly exceeded in our coverage area and most areas south of St. John indicating the potential for sediment mobilization in the predominant wave direction (toward our coverage area) (Fig. 6). St. John sits on a wide, low-gradient shelf (30–60 m water depth) that extends ~12 km south of St. John, an area of ~42.3 km2 (Fig. 2). We find the critical Shields parameter was exceeded throughout all but northern Coral Bay during both Irma and Maria, with much larger values for Maria (Fig. 6). Thus, Irma was likely responsible for breaking up and resuspending shelf sediments finer than medium sand south of St. John, while Maria (with larger wave heights, periods, and higher Shields parameter values) was more likely to transport the sediments into the study area (Figs 2 and 6). Waves recorded during Jose were not significant in height and were likely too small to transport any significant amount of sediment (Supplementary Fig. S1). Mineralogical results are consistent with this interpretation due to the large amounts of the marine-derived, carbonate mineral aragonite found in our coverage area (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S2). The aragonite likely comes from calcareous algae (possibly Halimeda spp., found in Coral Harbor77 and Core 2, Fig. 5) which dominantly exists from inner Coral Harbor to at least ~6 km offshore on the southern shelf of St. John77,78.

The recent nature of the large depositional event is confirmed with 7Be measurements of sediment grab and core samples. Half of the surficial sediment grab samples (~5 cm deep) contain 7Be, indicating recent deposition within the past year (Fig. 4). The downcore depth at which 7Be was detected, at least 0.8 cm in 3 cores, is representative of exceptionally high accumulation rates over the previous year45,61. The presence of 7Be can be diluted by large amounts of marine sediments, particularly coarse grained material as 7Be does not sorb well to large grains. The 7Be signal combined with surface mineralogy (Fig. 4) strongly suggest a recently deposited unit that is dominantly composed of marine-derived carbonate (Supplementary Table S2). However, 7Be only corroborates recent deposition and it may not be present throughout the new depositional layer. In fact, the layer change contact in Core 2 (~4 cm downcore), is 3.2 cm below detected 7Be (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table S1). The same location at Core 2 was previously cored in 200261, but does not show the ~4 cm capping layer (Fig. 5). In this region, the pre- and post-hurricane bathymetric difference map shows deposition from 1–39 cm. However, it should be noted that handheld GPS units used for the core locations introduce positional inaccuracies. Thus, the area over which the core could have been taken can vary by several meters (possibly contributing to the large disparity in thickness).

Despite an annual amount of rainfall recorded between bathymetric surveys (~1,260 mm), watershed modeling (Methods) suggest that land-derived sediment contributed a trivial portion (0.1%) of the total volume of sediment deposited. Detection of 7Be downcore shows that terrestrial deposition occurred but when compared to the marine-derived component, is insignificant. Importantly, even when accounting for 100% sediment delivery to the coast (Methods, Supplementary Methods), estimated terrestrial inputs, including hurricane induced surface erosion, treethrow, and streambank erosion, equal less than 0.2% of the total estimated depositional volume estimated by the bathymetric surveys. We therefore interpret that nearly all of the total depositional volume is composed of marine-derived sediment, which could include some terrestrial sediment already in the marine environment. The transport and deposition occurred during a 14-day window between Hurricanes Irma, Jose, and Maria, but primarily during Irma and Maria. This is supported by our wave modeling (Fig. 6), surface sediment sample mineralogy (Fig. 4), and the marine carbonate fragments found in the upper 4 cm of Core 2 (Fig. 5).

The volume of hurricane-induced deposition that occurred during a 14-day span in 2017 is approximately equivalent to several centuries of sediment accumulation under typical conditions (including hurricanes). Core-derived sediment accumulation rates were previously estimated in Coral Bay by Brooks et al.45,61. They report an overall accumulation rate of 0.08 cm yr−1 during the last few thousand years and 0.20 cm yr−1 over the last 100 years. The increase is attributed primarily to anthropogenic development and the expansion of the unpaved road network in coastal watersheds since mid-20th century61. The relative increase in sediment accumulation is similar to the sediment yields estimated for developed watersheds elsewhere in St. John79,80 (including our own sediment yield model). The average thickness of the new hurricane deposit (25 cm) equates to 313 years of pre-development sedimentation or 125 years of sediment accumulation under current conditions. The largest zone of deposition, on average ~50 cm thick (~263,000 m2 and ~130,000 m3; Fig. 3), equates to 625 years of sediment accumulation under pre-20th century style land development regime and 250 years under current development and sedimentation patterns. This suggests that an equivalent of several hundreds of years of deposition (which include hurricane signals) occurred within a 2-week span.

Irma and Maria likely caused partial or full burial of seagrasses, corals, and calcareous algae in the study area. The substrate of Coral Harbor, Sanders Bay and the nearshore of Johnson Bay was primarily composed of seagrass and calcareous algae (Thalassia spp., Syringodium spp., Halophila spp., Halodule spp., and Halimeda spp.)77,81. Of the four seagrass genus dominantly found on St. John, all have shown partial mortality when experimentally buried to 5 cm and two species experienced full mortality when buried 10 cm for 60 days or more31. Given the average depositional thickness observed in Coral Bay(~25 cm) and that the survey occurred ~80 days after the last possible burial event (Maria) and ~104 days after the first possible burial event (Irma), it is possible that widespread mortality occurred. However, both the seagrass Thalassia testudinum and calcareous algae Halimeda spp. are resilient and communities have previously recovered from hurricane effects25,31.

We have characterized the short-term distribution and nature of the storm event but the long-term fate of the depositional unit is unclear. Natural processes may redistribute and/or erode the deposit. If the layer is preserved, compaction and burial will decrease the vertical thickness of the storm layer. Linear accumulation rates, such as those established by Brooks et al.45,61 do not account for gravity compaction, which this layer has not yet experienced and could ultimately lead to a smaller depositional thickness.

We assume that Irma and Maria primarily contributed to the new deposit, however, we find no obvious indicators distinguishing the individual contributions of each hurricane. We consider that the rapid succession of three major hurricanes, rather than if the storms were spread out over time, played a role in the ~322,317 m3 sediment deposit. Conceivably, Irma (the strongest storm) primed the system by disturbing and resuspending deeper marine sediments while Maria assisted in further eroding and transporting these sediments to the coastal reaches of Coral Bay. Regardless, this new volume originated under atypical conditions (3 major hurricanes in rapid succession) and thus normal coastal circulation may or may not adjust to redistribute this deposit.

Coral Bay is similar to many tropical volcanic systems both in the Caribbean and in the southwest Pacific. Due to the projected increase in the frequency of storms and their intensity82,83 understanding landscape response is important for future planning. Sediment derived from storms are a risk to critical coastal ecosystems such as coral reefs and should be considered in hurricane management plans and impact models.

Methods

Multibeam Surveying

We conducted two surveys in Coral Bay, St. John, USVI with a 7.6 m survey vessel using a R2Sonic® 2020 multibeam echosounder equipped with varied power and internal motion and navigation (I2NS). An Applanix® PosM/V navigational gyroscope paired with two L2 phase antennae recorded the position and motion data. The system was compression-mounted to the port side of the vessel with a pole mount and stabilized to prevent vibration and translation.

Data was collected using QPS® QINsy hydrographic software and processed using Qimera. After the surfaces were cleaned, they were gridded to multiple cell sizes from 10 centimeters to 10 meters using the mean weighted average method.

A systematic error in depth occurred in the November survey. The shift was caused by a lack of additional GPS data, not allowing the coarse GPS and motion data to be post processed. To quantify the depth shift, the gridded surfaces were compared in a series of 2-D profiles across reef mounds in Johnson Bay whose elevation was not likely to change during the storms. In total 18 profiles and 5 structures were used to determine the offset. The average offset was −1.12 m with a maximum and minimum +/−0.12 m. It should be noted that the maximum offset yielded a depositional volume only 54% of the average offset depositional volume. The maximum offset still had an average depositional thickness of 10 cm. The minimum offset showed 30% greater deposition. The average offset was applied to the grid for the post-storm November dataset.

The November and August grids were differenced and each 0.10 m cell was assigned a single depth value. Each November 0.10 m grid cell was subtracted from the August survey 0.10 m grid cells creating a 0.10 m resolution difference map. Depositional volumes were calculated by summing the volumes of each individual cell in the difference map. As a check to the difference map, we examined several ~0.5 m deep depressions in Coral Harbor, which were observed in both surveys. Each depression profiled filled partially and had ~20–30 cm of deposition which correlates with the difference map, validating the average vertical offset of −1.12 m chosen for the November grid. We also assessed sensitivity to grid size spacing and depth uncertainty.

Sediment Samples

During the post-storm field event, we acquired surficial sediment grab samples and sediment cores in both 3″ diameter aluminum barrels and 4″ polycarbonate tubes at the same location (Figs 3 and 4). The aluminum cores were scanned with X-Ray Computed Tomography (XCT) at a resolution of 0.625 mm per slice. The aluminum cores were then split longitudinally, photographed, and visually described. The polycarbonate cores were extruded vertically and subsampled at 0.5 cm intervals for short-lived radioisotopic analysis. Beryllium-7 (7Be) has a very short half-life (~53 days) and is an indicator of recent sediment deposition (~1 yr) and preservation of the core top. 7Be activities were measured on surface sediments and extruded core samples at 0.5 cm resolution on a GWL Series HPGe (High-Purity Germanium) Coaxial Well Photon Detector. Data were corrected for counting time, detector efficiency and geometry, as well as for the fraction of the total radioisotope measured yielding activity in dpm/g (disintegrations per minute per gram) (Supplementary Table S1). Detector efficiency was determined using similar methods to Kitto84 using the IAEA 447 standard. A calibration template was produced relating the counts measured to the known activity of the standard for the range of sample weights. By using the calibration template for various weights, self-absorption of the sample is included in the detector efficiency calculations. Surficial sediment samples were analyzed for mineralogic composition by powder X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) on a Bruker D4 Endeavor X-Ray diffractometer and processed using the Rietveld method85,86.

Wave Modeling and Shields Parameter Calculation

A numerical simulation of the wave conditions associated with Hurricanes Irma and Maria was conducted in order to understand the potential for wave-induced sediment mobilization in and around Coral Bay. The simulation is based on the CARICOOS Nearshore Wave Model (CNWM), an operational model based on the Simulating WAves Nearshore (SWAN) spectral wave model which is described in detail in Booij et al.87. Additional details of the model setup and physics can be found in Anselmi et al.88, Canals et al.89, Canals and García90 and in Supplementary Methods. Wave conditions were simulated at very high spatial resolution (100 meters) in order to resolve wave transformation processes in the Virgin Islands shelf and in the complex coastline of St. John. A comparison between modeled and observed wave heights during the storms indicates the model captures the most important features of the wave events (Supplementary Fig. S1). Using the simulation results, we estimated maximum bottom shear stresses for each storm using the nondimensional Shields parameter formulation75 and compared the estimated values with the critical Shields parameter values that would be required for sediment mobilization (Supplementary Methods)76. We used standard values for seawater density and viscosity as well as locally observed grain sizes (Table 2)45. For grain density we used aragonite, a mineral dominantly found in Coral Bay43 (Supplementary Table S2). We used a Nikuradse roughness value proportional to the median sediment grain size (Supplementary Methods)73. It should be noted that, in reality, roughness values (and thus the associated shear stresses) would be much larger than the roughness corresponding to the median grain size, given the actual bedforms throughout the study site. However, in the absence of detailed information regarding physical bed roughness, using roughness values based on sediment grain size is a conservative estimate (and likely a significant underestimate) of the expected shear stresses.

Watershed Sediment Budget Modeling

Estimates of terrestrial sediment contribution relied on the STJ-EROS model80. STJ-EROS is a GIS-based framework that relies on locally-derived functions46,91 and sediment delivery ratios (SDRs) to estimate net erosion and sediment yields into coastal waters. The model contains separate algorithms for natural and roaded surfaces. STJ-EROS is meant as an annual-based sediment budgeting tool, yet functions associated to surface erosion from undisturbed hillslopes and roads are driven by rainfall amounts, thus allowing model application to shorter periods. Additionally, two hurricane events occurred during the field testing of the model and delivered similar rainfall (Supplemental Methods). However, the model is unable to account for gullying (visually observed in 2017) or mass wasting (not observed in 2017). Treethrow contributions assumed an 8.5 Mg per linear km of stream per event. This is a conservative value considering that surveys that lead to the original estimate used by STJ-EROS (17 Mg per km per year) integrated treethrow caused by category 3 and 4 hurricanes (Hurricanes Hugo in 1989 and Georges in 1998)92 and not Category 5 Hurricanes like Irma and Maria. However, this estimate may be considered high as it presupposes that all of the sediment uprooted by this process is dislodged from the rootwad and thus available for further transport during the storm event that triggered its uprooting. Streambank erosion in STJ-EROS is also based on an annual rate, but since the amount of rainfall, and presumably runoff, associated to the period of interest equals the annual normal, we presumed that streambanks could have released an amount of sediment similar to the annual average. Required model input geodatabases represented a 2011 road survey93, a 3.9 km km−2 DEM-based stream network relying on a 0.1 ha source area threshold50 and a 2015 streambank field survey94.

The estimated sediment yield rate in STJ-EROS relies on user-defined SDRs, where SDR is the ratio of sediment delivered to the gross erosion occurring within the basin95. Given the small size and steep relief of catchments draining into Coral Bay (<10 km2), their SDR values are expected to be high. However, sediment delivery is confounded by the presence of coastal wetlands for which no empirical evidence exists on its sediment retention capacities. Therefore, watersheds draining through wetlands before delivering runoff into Coral Bay received a SDR value of 25%, while those directly draining into coastlines without an intervening wetland were assigned a SDR of 75%. The true sediment yield to coastal waters from all processes included in STJ-EROS likely lies between the model’s yield and net sediment production estimates.

The 7.3 km2 source area draining towards Coral Bay has a total of 27.8 km of gullies (i.e., ephemeral streams), but only of 4.9 km of those have erodible streambanks94. There are a total of 38.3 km of roads within the area draining into Coral Bay and 21.3 km of those are unpaved94. Only 29% of the source area is considered as having a high sediment delivery potential. Estimated sediment yield and total sediment produced for the period of interest are 280 and 560 Mg, respectively. The model estimates that these rates of sediment yield and production are 2.0 to 2.7 times above natural rates and that between 51% and 63% of this sediment is generated from unpaved roads.

Data Availability

All data used for this study have been provided either in the text, supplementary material or are available through the National Science Foundation at www.data.gov (search our grant number, OCE-1762346).

References

Montz, B. E., Tobin, G. A. & Hagelman, R. R. III. Natural Hazards, Second Edition: Explanation and Integration (Guilford Publications, 2017).

Aguada, E. & Burt, J. Understanding Weather And Climate. 7th edn (Pearson Education, 2015).

Caro, T., Dobson, A., Marshall, A. J. & Peres, C. A. Compromise solutions between conservation and road building in the tropics. Curr Biol 24, R722–725, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.007 (2014).

Harding, S. M., Wolff, M., Trewin, D. & Hunter, S. State of the Tropics. 243 (James Cook University, Cairns, Australia, 2014).

Rogers, C. S. Responses of coral reefs and reef organisms to sedimentation. Marine ecology progress series, 185–202 (1990).

Wilkinson, C. & Salvat, B. Coastal resource degradation in the tropics: does the tragedy of the commons apply for coral reefs, mangrove forests and seagrass beds. Mar Pollut Bull 64, 1096–1105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.01.041 (2012).

Kosciuch, T. J. et al. Foraminifera reveal a shallow nearshore origin for overwash sediments deposited by Tropical Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu (South Pacific). Marine Geology 396, 171–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2017.06.003 (2018).

Edmunds, P. J. & Gray, S. C. The effects of storms, heavy rain, and sedimentation on the shallow coral reefs of St. John, US Virgin Islands. Hydrobiologia 734, 143–158, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-014-1876-7 (2014).

Rogers, C. S. & Miller, J. Permanent ‘phase shifts’ or reversible declines in coral cover? Lack of recovery of two coral reefs in St. John, US Virgin Islands. Marine Ecology Progress Series 306, 103–114 (2006).

Bégin, C. et al. Increased sediment loads over coral reefs in Saint Lucia in relation to land use change in contributing watersheds. Ocean & Coastal Management 95, 35–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.03.018 (2014).

Hawkins, J. P., Roberts, C. M., Dytham, C., Schelten, C. & Nugues, M. M. Effects of habitat characteristics and sedimentation on performance of marine reserves in St. Lucia. Biological Conservation 127, 487–499, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.008 (2006).

White, A. T., Vogt, H. P. & Arin, T. Philippine coral reefs under threat: the economic losses caused by reef destruction. Marine Pollution Bulletin 40, 598–605 (2000).

Barbier, E. B. et al. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecological monographs 81, 169–193 (2011).

Moberg, F. & Folke, C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecological economics 29, 215–233 (1999).

Aronson, R. B., Sebens, K. P. & Ebersole, J. P. Hurricane Hugo’s impact on Salt River submarine canyon, St. Croix, US Virgin Islands in Proc Colloquium on Global Aspects of Coral Reefs: Health, Hazards and History. Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, Miami. 189–195 (1994).

Bjork, M., Mohammed, S. M., Bjorklund, M. & Semesi, A. Coralline algae, important coral-reef builders threatened by pollution. Ambio 24, 502–505 (1995).

Bujang, J. S., Zakaria, M. H. & Arshad, A. Distribution and significance of seagrass ecosystems in Malaysia. Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management 9, 203–214, https://doi.org/10.1080/14634980600705576 (2006).

Beck, M. W. et al. The Identification, Conservation, and Management of Estuarine and Marine Nurseries for Fish and InvertebratesA better understanding of the habitats that serve as nurseries for marine species and the factors that create site-specific variability in nursery quality will improve conservation and management of these areas. BioScience 51, 633–641https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568 (2001) 051[0633:TICAMO]2.0.CO; 2 (2001).

Sheppard, C., Dixon, D. J., Gourlay, M., Sheppard, A. & Payet, R. Coral mortality increases wave energy reaching shores protected by reef flats: Examples from the Seychelles. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 64, 223–234, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2005.02.016 (2005).

Irving, A. D., Connell, S. D. & Russell, B. D. Restoring coastal plants to improve global carbon storage: reaping what we sow. PLoS One 6, e18311, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018311 (2011).

Tilmant, J. T. et al. Hurricane Andrew’s effects on marine resources: the small underwater impact contrasts sharply with the destruction in mangrove and upland-forest communities. BioScience 44, 230–237 (1994).

Dawes, C. et al. Initial effects of Hurricane Andrew on the shoreline habitats of southwestern Florida. Journal of Coastal Research, 103–110 (1995).

Kendall, M. S., Battista, T. & Hillis-Starr, Z. Long term expansion of a deep Syringodium filiforme meadow in St. Croix, US Virgin Islands: the potential role of hurricanes in the dispersal of seeds. Aquatic Botany 78, 15–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2003.09.004 (2004).

Hillis, Z. & Bythell, J. “Keep up or give up”: hurricanes promote coral survival by interrupting burial from sediment accumulation. Coral Reefs 17, 262–262 (1998).

van Tussenbroek, B. I., Barba Santos, M. G., van Dijk, J. K., Sanabria Alcaraz, S. N. M. & Téllez Calderón, M. L. Selective Elimination of Rooted Plants from a Tropical Seagrass Bed in a Back-Reef Lagoon: A Hypothesis Tested by Hurricane Wilma. Journal of Coastal Research 241, 278–281, https://doi.org/10.2112/06-0777.1 (2008).

Thompson, J. H. Jr., Shinn, E. A. & Bright, T. J. Effects of drilling mud on seven species of reef-building corals as measured in the field and laboratory In Elsevier Oceanography Series Vol. 27 433–453 (Elsevier, 1980).

Cruz-Palacios, V. & van Tussenbroek, B. I. Simulation of hurricane-like disturbances on a Caribbean seagrass bed. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 324, 44–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2005.04.002 (2005).

Preen, A., Long, W. L. & Coles, R. Flood and cyclone related loss, and partial recovery, of more than 1000 km2 of seagrass in Hervey Bay, Queensland, Australia. Aquatic Botany 52, 3–17 (1995).

Moncreiff, C. et al. Short-term effects of Hurricane Georges on seagrass populations in the north Chandeleur Islands: Patterns as a function of sampling scale. Gulf Research Reports 11, 74–75 (1999).

Heck, K., Sullivan, M., Zande, J. & Moncrieff, C. An ecological analysis of seagrass meadows of the Gulf Islands National Seashore. Final Report to the National Park Service, Gulf Islands National Seashore, Gulf Breeze, Florida (1996).

Cabaço, S., Santos, R. & Duarte, C. M. The impact of sediment burial and erosion on seagrasses: A review. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 79, 354–366, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2008.04.021 (2008).

Ridler, M. S., Dent, R. C. & Arrinton, D. A. Effects of two hurricanes onSyringodium filiforme, manatee grass, within the Loxahatchee River estuary, Southeast Florida. Estuaries and Coasts 29, 1019–1025 (2006).

Duarte, C. M. et al. Response of a mixed Philippine seagrass meadow to experimental burial. Marine Ecology Progress Series 147, 285–294 (1997).

Wesseling, I., Uychiaoco, A. J., Aliño, P. M., Aurin, T. & Vermaat, J. E. Damage and recovery of four Philippine corals from short-term sediment burial. Marine Ecology Progress Series 176, 11–15 (1999).

Bythell, J. C., Hillis-Starr, Z. M. & Rogers, C. S. Local variability but landscape stability in coral reef communities following repeated hurricane impacts. Marine Ecology Progress Series 204, 93–100 (2000).

Rice, S. A. & Hunter, C. L. Effects of suspended sediment and burial on scleractinian corals from west central Florida patch reefs. Bulletin of Marine Science 51, 429–442 (1992).

Edmunds, P. J. & Witman, J. D. Effect of Hurricane Hugo on the primary framework of a reef along the south shore of St. John, US Virgin Islands. Marine Ecology Progress Series 78, 201–204, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps078201 (1991).

Michot, T. C. et al. Impacts of Hurricane Mitch on seagrass beds and associated shallow reef communities along the Caribbean coast of Honduras and Guatemala. (US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey, 2002).

Rogers, C. S., McLain, L. N. & Tobias, C. R. Effects of Hurricane Hugo (1989) on a coral reef in St. John, USVI. Marine Ecology Progress Series 78, 189–199, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps078189 (1991).

Woodley, J. et al. Hurricane Allen’s impact on Jamaican coral reefs. Science 214, 749–755 (1981).

Bythell, J., Gladfelter, E. & Bythell, M. Chronic and catastrophic natural mortality of three common Caribbean reef corals. Coral Reefs 12, 143–152 (1993).

Rankin, D. W. Geology of St. John, US Virgin Islands (US Geological Survey, 2002).

Browning, T. N. et al. Linking Land & Sea: Watershed Evaluation and Mineralogical Distribution of Sediments in Eastern St. John, USVI. Caribbean Journal of Science 49, 38–56, https://doi.org/10.18475/cjos.v49i1.a5 (2016).

Donnelly, T. W. Geology of St. Thomas and St. John, US Virgin Islands. Caribbean Geological Investigations. Geological Society of America Memoir 98, 5–176 (1966).

Brooks, G. R., Larson, R. A., Devine, B. & Schwing, P. T. Annual to millennial record of sediment delivery to US Virgin Island coastal environments. The Holocene 25, 1015–1026, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683615575357 (2015).

Ramos-Scharrón, C. E. & MacDonald, L. H. Measurement and prediction of sediment production from unpaved roads, St John, US Virgin Islands. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 30, 1283–1304, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.1201 (2005).

WRI & NOAA. Relative Vulnerability to Erosion: St. John, USVI. 211 (Department of Planning and Natural Resources; University of the Virgin Islands, St. Croix, USVI, 2005).

Larson, R. A. et al. Elemental signature of terrigenous sediment runoff as recorded in coastal salt ponds: US Virgin Islands. Applied Geochemistry 63, 573–585, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2015.01.008 (2015).

Cosner, O. J. Water in St. John, US Virgin Islands. Report No. 2331–1258, (US Geological Survey, Reston, VA, USA, 1972).

Ramos-Scharrón, C. E. & LaFevor, M. C. The role of unpaved roads as active source areas of precipitation excess in small watersheds drained by ephemeral streams in the Northeastern Caribbean. Journal of Hydrology 533, 168–179, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.11.051 (2016).

Ramos-Scharrón, C. E. & LaFevor, M. C. Effects of forest roads on runoff initiation in low-order ephemeral streams. Water Resources Research. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018wr023442 (2018).

Cangialosi, J. P., Latto, A. S. & Berg, R. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Irma. 111 (NOAA, 2018).

Blake, E. S., Landsea, C. & Gibney, E. J. The deadliest, costliest, and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts). (NOAA/National Weather Service, National Centers for Environmental Prediction, National Hurricane Center Miami, 2011).

Berg, R. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Jose. 36 (NOAA, 2018).

Pasch, R., Penny, A. & Berg, R. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria. 48 (NOAA, 2018).

NOAA. National Data Buoy Center, http://www.ndbc.noaa.gov/station_page.php?station=41052 (2018).

Morton, R. A., Gelfenbaum, G. & Jaffe, B. E. Physical criteria for distinguishing sandy tsunami and storm deposits using modern examples. Sedimentary Geology 200, 184–207 (2007).

Goff, J., Chagué-Goff, C., Nichol, S., Jaffe, B. & Dominey-Howes, D. Progress in palaeotsunami research. Sedimentary Geology 243, 70–88 (2012).

Donnelly, J. P. et al. Sedimentary evidence of intense hurricane strikes from New Jersey. Geology 29, 615–618 (2001).

Ganju, N. K. et al. Quantification of Storm-Induced Bathymetric Change in a Back-Barrier Estuary. Estuaries and Coasts 40, 22–36, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-016-0138-5 (2016).

Brooks, G. R., Devine, B., Larson, R. A. & Rood, B. P. Sedimentary development of Coral Bay, St. John, USVI: a shift from natural to anthropogenic influences. Caribbean Journal of Science 43, 226–243 (2007).

Miner, M. D., Kulp, M. A., FitzGerald, D. M. & Georgiou, I. Y. Hurricane-associated ebb-tidal delta sediment dynamics. Geology 37, 851–854, https://doi.org/10.1130/g25466a.1 (2009).

Claudino-Sales, V., Wang, P. & Horwitz, M. H. Effect of Hurricane Ivan on Coastal Dunes of Santa Rosa Barrier Island, Florida: Characterized on the Basis of Pre- and Poststorm LIDAR Surveys. Journal of Coastal Research 263, 470–484, https://doi.org/10.2112/08-1105.1 (2010).

Goff, J. A. et al. The impact of Hurricane Sandy on the shoreface and inner shelf of Fire Island, New York: Large bedform migration but limited erosion. Continental Shelf Research 98, 13–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2015.03.001 (2015).

Kreisa, R. D. Storm-generated sedimentary structures in subtidal marine facies with examples from the Middle and Upper Ordovician of southwestern Virginia. Journal of Sedimentary Research 51, 823–848 (1981).

Kraft, B. J. & de Moustier, C. Detailed Bathymetric Surveys Offshore Santa Rosa Island, FL: Before and After Hurricane Ivan (September 16, 2004). IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 35, 453–470, https://doi.org/10.1109/joe.2010.2052970 (2010).

Sopkin, K. L. et al. Hurricane Sandy: observations and analysis of coastal change, https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20141088 (2014).

Collins, E., Scott, D. B. & Gayes, P. Hurricane records on the South Carolina coast: can they be detected in the sediment record? Quaternary International 56, 15–26 (1999).

Hawkes, A. D. & Horton, B. P. Sedimentary record of storm deposits from Hurricane Ike, Galveston and San Luis Islands, Texas. Geomorphology 171-172, 180–189, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.05.017 (2012).

Cahoon, D. R. A review of major storm impacts on coastal wetland elevations. Estuaries and Coasts 29, 889–898 (2006).

Horton, B. P., Rossi, V. & Hawkes, A. D. The sedimentary record of the 2005 hurricane season from the Mississippi and Alabama coastlines. Quaternary International 195, 15–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2008.03.004 (2009).

Hubbard, D. K. Hurricane-induced sediment transport in open-shelf tropical systems; an example from St. Croix, US Virgin Islands. Journal of Sedimentary Research 62, 946–960 (1992).

Deigaard, R. Mechanics of coastal sediment transport. Vol. 3 (World scientific publishing company, 1992).

Roulund, A., Sutherland, J., Todd, D. & Sterner, J. In Scour and Erosion: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Scour and Erosion. 313 (CRC Press) (Oxford, UK, 12–15 September 2016).

Shields, A. Application of similarity principles and turbulence research to bed-load movement (1936).

Soulsby, R. & Whitehouse, R. Threshold of sediment motion in coastal environments In Pacific Coasts and Ports’ 97: Proceedings of the 13th Australasian Coastal and Ocean Engineering Conference and the 6th Australasian Port and Harbour Conference; Volume 1. 145 (Centre for Advanced Engineering, University of Canterbury) (1997).

Whitall, D., Menza, C. & Hill, R. A Baseline Assessment of Coral and Fish Bays (St. John, USVI) in Support of ARRA Watershed Restoration Activities. 85 (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, 2014).

Costa, B. M., Bauer, L. J., Battista, T. A., Mueller, P. W. & Monaco, M. E. Moderate-Depth Benthic Habitats of St. John, US Virgin Islands (2009).

Anderson, D. M. & Macdonald, L. H. Modelling road surface sediment production using a vector geographic information system. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 23, 95–107, https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9837(199802)23:2<95::AID-ESP849>3.0.CO;2-1 (1998).

Ramos-Scharrón, C. E. & MacDonald, L. H. Development and application of a GIS-based sediment budget model. Journal of Environmental Management 84, 157–172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.05.019 (2007).

Friedlander, A. M. et al. Coral reef ecosystems of St. John, US Virgin Islands: spatial and temporal patterns in fish and benthic communities (2001–2009) (2013).

Emanuel, K. Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature 436, 686 (2005).

O’Gorman, P. A. Precipitation extremes under climate change. Current climate change reports 1, 49–59 (2015).

Kitto, M. E. Determination of photon self-absorption corrections for soil samples. International journal of radiation applications and instrumentation. Part A. Applied radiation and isotopes 42, 835–839 (1991).

Dinnebier, R. E. & Billinge, S. J. Powder diffraction: theory and practice (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2008).

Rietveld, H. M. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. Journal of applied Crystallography 2, 65–71 (1969).

Booij, N., Ris, R. C. & Holthuijsen, L. H. A third‐generation wave model for coastal regions: 1. Model description and validation. Journal of Geophysical Research 104, 7649–7666 (1999).

Anselmi-Molina, C. M. et al. Development of an operational nearshore wave forecast system for Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. 28, 1049–1056 (2012).

Canals, M., Morell, J., Corredor, J. E. & Leonardi, S. In 2012 Oceans. 1–4 (IEEE).

Silander, M. F. C. & Moreno, C. G. G. J. R. E. On the spatial distribution of the wave energy resource in Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands 136, 442–451 (2019).

Ramos-Scharrón, C. E. & MacDonald, L. H. Measurement and prediction of natural and anthropogenic sediment sources, St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands. Catena 71, 250–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2007.03.009 (2007).

Ramos-Scharrón, C. E. Measuring and predicting erosion and sediment yields on St. John, US Virgin Islands, PhD Thesis, Colorado State University (2004).

Ramos Scharrón, C. E., Reale-Munroe, K., Swanson, B., Atkinson, S. C. & Devine, B. Habitat Restoration through Watershed Stabilization Project, NOAA-ARRA, 2009–2012, Terrestrial Monitoring Component, 242 p (2012).

Ramos Scharrón, C. E. unpublished data (2015).

De Vente, J., Poesen, J., Arabkhedri, M. & Verstraeten, G. The sediment delivery problem revisited. Progress in Physical Geography 31, 155–178 (2007).

NOAA. in U.S. Virgin Islands 1 arc-second MHW Coastal Digital Elevation Model (eds NESDIS National Centers for Environmental Information, NOAA, U.S. Department of Commerce & National Geophysical Data Center) (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, Silver Spring, MD, 2014).

USACE. In US Virgin Islands Orthophoto Mosaic (ed US Army Corps of Engineers) (US Army Corps of Engineers, Peachtree City, GA, USA, 2008).

Acknowledgements

The post-hurricane response was supported by National Science Foundation grant OCE-1762346. We thank Brandi Lenz, Alex Holderness, Capt. Jason Siska (Island Roots), and Jason Hayman for fieldwork assistance. All rainfall data provided by Rafe Boulon, Trunk Bay, St. John.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.N.B. and D.E.S. collected field data and drafted the manuscript. T.N.B. processed multibeam and mineralogy data. G.B. and R.L. analyzed 7Be and mineralogy data and finalized the manuscript. C.R.S. provided watershed analysis, contributed to the discussion, and finalized the manuscript. M.C.S. provided wave and sediment transport analysis, and contributed to the discussion. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41598_2019_43062_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary Material for Widespread Deposition in a Coastal Bay Following Three Major 2017 Hurricanes (Irma, Jose, and Maria)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Browning, T.N., Sawyer, D.E., Brooks, G.R. et al. Widespread Deposition in a Coastal Bay Following Three Major 2017 Hurricanes (Irma, Jose, and Maria). Sci Rep 9, 7101 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43062-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43062-4

This article is cited by

-

Portfolio effects and functional redundancy contribute to the maintenance of octocoral forests on Caribbean reefs

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

The Far Reach of Hurricane Maria:

Economics of Disasters and Climate Change (2022)

-

Vulnerability to watershed erosion and coastal deposition in the tropics

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Vulnerability assessment of nearshore clam habitat subject to storm waves and surge

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

3D assessment of a coral reef at Lalo Atoll reveals varying responses of habitat metrics following a catastrophic hurricane

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.