Abstract

Extraordinary photovoltaic performance and intriguing optoelectronic properties of perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have aroused enormous interest from both academic research and photovoltaic (PV) industry. In order to bring PSC technology from laboratory to market, material stability, device flexibility, and scalability are important issues to address for vast production. Nevertheless, PSCs are still primarily prepared by solution methods which limit film scalability, while high-temperature processing of metal oxide electron transport layer (ETL) makes PSCs costly and incompatible with flexible substrates. Here, we demonstrate rarely-reported room-temperature radio frequency (RF) sputtered SnO2 as a promising ETL with suitable band structure, high transmittance, and excellent stability to replace its solution-processed counterpart. Power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) of 12.82% and 5.88% have been achieved on rigid glass substrate and flexible PEN substrate respectively. The former device retained 93% of its initial PCE after 192-hour exposure in dry air while the latter device maintained over 90% of its initial PCE after 100 consecutive bending cycles. The result is a solid stepping stone toward future PSC all-vapor-deposition fabrication which is being widely used in the PV industry now.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) as a promising and emerging photovoltaic (PV) technology have quickly caught enormous attention in both academic research and PV industry over the past few years. As one of the most intensively researched types of solar cells, PSCs have been rapidly developed with unprecedented success, leading to a significant improvement on power conversion efficiency (PCE) from 3.8% to certified 22.7% within a decade1,2. Besides high device performance, low fabrication cost as well as tunable composition and bandgap give this group of semiconductors gigantic potential and intriguing optoelectronic properties for next-generation solar cell3. Crystal growth optimization, interfacial engineering, compositional optimization, and device architecture design have been further explored to enhance PCE and stability of devices and eventually make them competitive with conventional silicon and other leading thin film solar cell technologies4,5,6,7,8.

Typically, a PSC consists of an electron transport layer (ETL), a perovskite film and a hole transport layer (HTL), in addition to top and bottom electrical contacts. Particularly, inorganic metal-oxide films, such as TiO2 and ZnO, have been widely reported as effective ETLs for high-performance PSCs9,10,11,12,13,14. Nevertheless, they both have major drawbacks. TiO2 as the most commonly used ETL has low electron mobility and requires sintering at high temperature up to 500 °C15,16,17,18,19. High temperature processing not only increases the cost of device fabrication, but also restricts the compatibility with flexible substrates. In addition, TiO2 provokes perovskite degradation under exposure of UV illumination which is problematic during the prolonged device operation20. On the other hand, the hygroscopic nature of ZnO easily causes perovskite decomposition in moisture environment. Moreover, ZnO has poor thermal stability so it can easily react with perovskite during annealing and thermal treatment at elevated temperature, which eventually stimulates undesired perovskite degradation or even decomposition. Like perovskite, TiO2 and ZnO are mostly prepared by solution methods, which sacrifice film uniformity and limit large-scale device production. On the other hand, SnO2 is regarded as an alternative to replace TiO2 and ZnO as an effective ETL to achieve low-cost PSCs with improved stability21,22. SnO2 has a wider bandgap and its electron mobility is two orders of magnitude higher than that of TiO2, making it a more suitable candidate for use in high performance devices23. Compare to TiO2 and ZnO, SnO2 is less hygroscopic in nature, has better thermal and UV stability, and possesses lower photocatalytic activity24. These properties prevent perovskite degradation and benefit PSC long-term stability. Despite that high-performance PSCs based on SnO2 have been achieved, almost all reported SnO2 films were prepared by spin-coating25,26,27,28,29,30, atomic layer deposition (ALD)31,32, plasma-enhanced ALD33, sol-gel process34, chemical bath deposition35, hydrothermal process36, and electrodeposition37. In fact, many of these methods involve high-temperature processing and annealing ranging from 100 °C up to 550 °C, which again increases fabrication complexity and cost and makes it incompatible with flexible substrates. In order to make PSC technology cost-effective in the future, a fabrication technique allowing vast production is absolutely necessary.

Considering the high reliability, maturity, and capability for large-scale production of sputtering technique in both industries and laboratories, SnO2 prepared by magnetron sputtering for PSC application is however rarely reported38. And previously studied sputtered SnO2 film was calibrated based on deposition time instead of thickness, which is a more accurate and reliable approach in principle since deposition time depends on a number of deposition parameters and equipment infrastructure. Moreover, previous study lacked investigation on device stability as well as thorough thin film characterization on their SnO2 and the corresponding glovebox-processed spin-coated perovskite absorber, particularly morphology and crystallinity analysis by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and photoluminescence (PL). Therefore, it was hard to convince the effectiveness and compatibility of sputtered SnO2 with perovskite solar cells. On the other hand, perovskite films are typically prepared by solution methods inside a glovebox filled with inert gas. Similarly, those solution methods limit film scalability while the use of glovebox increases production cost and complexity. Researchers have therefore put a great amount of effort to fabricate perovskite films and devices in ambient condition without sacrificing film quality, device performance, as well as stability19,39.

Here, we demonstrate room-temperature RF sputtered SnO2 film as an effective and robust ETL and meanwhile take one step forward to implement it together with vapor-deposited perovskite absorber for air-stable and efficient PSCs on both rigid and flexible substrates. By this application, we are now only one step away from sputtered SnO2 based all-vacuum-deposited perovskite solar cells which will eventually enable industrialization. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report of using sputtered SnO2 for flexible PSCs application. Both SnO2 thickness and deposition conditions including working pressure and gas environment were systematically investigated. Device stability and hysteresis were also carefully studied.

Results and Discussion

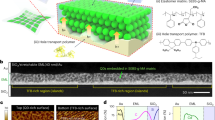

In this work, we demonstrated n-i-p planar structure of PSCs with optimized room-temperature-processed SnO2 as ETL prepared by RF magnetron sputtering and vacuum-deposited perovskite film. Figure 1a shows the schematic of device structure of our PSCs: ITO-PEN/SnO2/MAPbI3/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au. Figure 1b,c display SEM images of complete device based on rigid FTO glass substrate and flexible ITO-PEN substrate respectively. The morphology and surface roughness of bare FTO (Supplementary Fig. S1), 40 nm SnO2-coated FTO (Fig. 2a,b), and solution-processed SnO2 (Fig. 2c,d) were studied by SEM and atomic force microscopy (AFM). Supplementary AFM reveals the root-mean-square (RMS) roughness and mean roughness of bare FTO glass were 7.736 nm and 6.096 nm respectively. In contrast, 40 nm SnO2-coated FTO had a RMS roughness and mean roughness of 5.488 nm and 4.358 nm respectively, while solution-processed SnO2 had higher RMS roughness and mean roughness of 6.439 nm and 5.000 nm. It is reflected that sputtered SnO2 film was uniformly deposited on FTO surface and SnO2 grains were small enough to fill in the gaps between FTO grains, leading to a lower surface roughness than solution-processed SnO2, which is beneficial for the growth of vapor-deposited perovskite. To illustrate how surface roughness matters, perovskite was vapor-deposited on a 10 nm SnO2-coated FTO with RMS roughness and mean roughness of 7.199 nm and 5.708 nm respectively, measured by AFM (Supplementary Fig. S2). It was clear that perovskite grain sizes on the 10 nm SnO2-coated FTO were significantly reduced (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Moreover, cross-sectional SEM shown in Supplementary Fig. S3b reveals that the perovskite grains and shape became more irregular on 10 nm SnO2-coated FTO, while single-crystal-thick perovskite grains with larger grain sizes and regular shapes were crystallized on 40 nm SnO2-coated FTO (Supplementary Fig. S3c,d). In addition, small perovskite grains tended to crystallize in the perovskite-SnO2 interface on 10 nm SnO2-coated FTO, which could adversely affect the efficiency of carrier transport. Since materials were slowly deposited onto substrate down to a few angstroms per second, a rougher surface would hinder the ion migration and volumetric expansion as perovskite crystallization took place. In contrast, this problem becomes less significant when perovskite is prepared by solution methods because they allow ions within the precursors to easily spread all over the substrates without overcoming significant energy barriers. Therefore, this problem was not commonly discussed in depth before. In contrast, although perovskite grown on solution-processed SnO2 film (Supplementary Fig. S4) demonstrated comparable grain size with those grown on sputtered SnO2, the former perovskite films exhibit layered structure on most of the grains. This could be attributed to the higher roughness of solution-processed SnO2 film, leading to inconsistent rate and degree of perovskite crystallization and ultimately high surface roughness. These could increase the probability of carrier recombination between perovskite absorber and the HTL.

The full ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) spectrum of sputtered SnO2 is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5a. The sputtered SnO2 film showed a secondary cutoff edge of 5.01 eV (Supplementary Fig. S5b), indicating a work function WS of 5.01 eV. Supplementary Fig. S5c shows the valence band maximum (VBM) of the sputtered SnO2 film is located at 3.07 eV, below EF. The bandgap of the sputtered SnO2 film acquired from the Tauc plot (Fig. 3a) was 3.72 eV, which is wider than that of ZnO and TiO2. A wider bandgap implies better hole blocking ability and can avoid absorption of high-energy photons which leads to small current loss40. Based on the above values, it can be calculated using the semiconductor band structure (EC = WS + VBM − Eg) that the EC of the sputtered SnO2 film was 4.36 eV, which is deeper than that of TiO2 and ZnO, both are 4.2 eV. The deeper conduction band of SnO2 compared to TiO2 and ZnO could enhance electron transfer from perovskite to the ETL. On the other hand, calculation showed EV of the sputtered SnO2 film was 8.08 eV, which is much deeper than that of TiO2 and ZnO, 7.4 eV and 7.6 eV respectively. The deeper valence band of SnO2 can enhance hole blocking ability from perovskite to the ETL. Figure 3b shows the energy band diagram of each device component and the transportation of photo-generated electrons and holes.

Being an effective ETL for PSCs of n-i-p planar structure, transmittance, thickness, and film quality are crucial. XRD (Fig. 3c) revealed that both sputtered and solution-processed SnO2 films were polycrystalline but the former one exhibited better crystallinity. All XRD peaks for SnO2 were indexable to the tetragonal SnO2 structure, indicating the formation of pure SnO2 crystals. In addition, sputtered SnO2 film on FTO glass showed good transparency with transmittance close to 90% in the visible region (Fig. 3d), while solution-processed SnO2 had lower transmittance of about 80%. It is noteworthy the room-temperature sputtered SnO2 here demonstrated even higher transmittance than other high-temperature-processed spin-coated SnO2 films41. To obtain high-quality SnO2 films, impact of thickness, sputtering working pressure, and the flow rates of O2 and Ar during sputtering were systematically studied.

Since the thickness of ETL can critically affect cell performance, SnO2 film was first sputtered under the same sputtering power of 60 W on FTO glass substrates kept at room temperature with four different thicknesses, 20 nm, 40 nm, 60 nm, and 80 nm, which took 8 min, 15 min, 23 min, and 30 min for sputtering, respectively. It can be inferred that the deposition rate was approximately 0.43 Å s−1. After sputtering, SnO2-coated FTO substrates were transferred to the evaporator for perovskite fabrication via a two-step vapor deposition as described in the Method section. The as-deposited perovskite samples were annealed in ambient air condition with over 65% humidity. It has been reported that certain level moisture is helpful for perovskite crystallization but excessive moisture could be detrimental to perovskite42. To overcome the humidity problem, perovskite samples were annealed for a short period of time at elevated temperature to accelerate the perovskite crystallization process and meanwhile minimize perovskite film degradation in ambient condition39,43,44. As-deposited perovskite samples were annealed at 130 °C for 10 min instead of the conventional 100 °C for an hour. It turned out that this method is also workable for vapor-deposited perovskite films, not only for solution-processed perovskite films. The UV-vis absorption spectra shown in Fig. 4a of the vapor-deposited perovskite shows good absorption in the visible region. It also revealed that perovskite grown on sputtered SnO2 exhibited higher absorption than that grown on solution-processed SnO2, which was attributed to its lower transmittance than sputtered SnO2. The absorption onset corresponded to an optical bandgap of 1.57 eV, estimated from the Tauc plot (Supplementary Fig. S6). The estimation matches well with the perovskite PL peak at 788 nm and the steady PL showed a more significant quench when depositing the perovskite film on sputtered SnO2 compared to solution-processed SnO2 (Fig. 4b). It supports that sputtered SnO2 possessed more efficient electron transport ability. XRD of perovskite (Fig. 4c) presented the expected perovskite pattern, with intense signals at 14.1°, 28.4°, and 31.9° corresponding to the (100), (200), and (310) directions, respectively. It showed an extra peak of PbI2 at 12.7° for perovskite that underwent 30 min prolonged annealing in humid air condition. Supplementary Fig. S7 shows the SEM of perovskite annealed for 30 min. The perovskite decomposing into PbI2 hindered its crystallization by grain boundary expansion and grain cracking. As a consequence, the intensity of each perovskite peak was clearly reduced as shown in Fig. 4c. It confirms the effectiveness of short-time annealing processing at elevated temperature in ambient condition.

Properties of vapor-deposited perovskite film. (a) Ultraviolet-visible spectrum (UV-vis) of vapor-deposited MAPbI3 grown on sputtered and spin-coated SnO2 films. (b) Photoluminescence (PL) spectrum of vapor-deposited MAPbI3 deposited on sputtered and spin-coated SnO2 films. (c) XRD of vapor-deposited perovskite in different conditions.

The J-V characteristics of devices based on FTO glass substrates with different SnO2 thicknesses measured under AM1.5G illumination are shown in Fig. 5a. The device performance firstly increased and then decreased as the sputtered SnO2 thickness increased. It is seen that devices with 40 nm SnO2 yielded the best performance, with a PCE of 11.14%, a VOC of 0.934 V, a JSC of 22.91 mAcm−2, and a fill factor (FF) of 52.1%, so 40 nm was taken as the optimum thickness. If the SnO2 layer was too thin, it could not fully cover the FTO surface for effective electron transport. On the other hand, a too thick SnO2 layer would induce a larger series resistance.

Device performance of perovskite solar cells based on sputtered SnO2 and solution-processed SnO2. J-V characteristics based on (a) different SnO2 thickness, (b) 40 nm SnO2 sputtered at different working pressures, and (c) 40 nm SnO2 sputtered at 0.25 Pa working pressure in different O2 to Ar flow rate ratios. J-V characteristics of the champion perovskite solar cell based on (d) optimized sputtered SnO2 and (e) solution-processed SnO2 measured under reverse and forward voltage scanning with AM1.5G illumination. (f) EQE curves of the champion devices based on sputtered and solution-processed SnO2 respectively.

The sputtering working pressure is another critical factor to determine the sputtered film quality. We fabricated PSCs based on 40 nm SnO2 sputtered under the same power of 60 W but three different working pressures, 0.25 Pa, 0.5 Pa, and 1.0 Pa. The J-V characteristics of respective devices are shown in Fig. 5b. The device performance, particularly the VOC, decreased as working pressure increased. It is seen that devices with SnO2 sputtered at 0.25 Pa yielded the best performance, with a PCE of 12.18%, a VOC of 0.948 V, a JSC of 22.34 mAcm−2, and an FF of 57.5%, so 0.25 Pa was taken as the optimum working pressure. An optimum working pressure is important so that the mean free path of gas molecules (O2 and Ar) is comparable to the distance between the target and substrates. A high working pressure will reduce the mean free path of molecules. In other words, there will be so much scattering that electrons will not have enough time to gather enough energy between collisions to ionize the atoms on the target. As a result, it causes a less uniform film deposition over the substrates. The reduced VOC is attributed to uneven deposition due to too high working pressure. Sputtering under working pressure below 0.25 Pa was attempted, however, the plasma became unsustainable and unstable around 0.2 Pa due to too low gas molecule concentration. In order to yield a self-sustaining plasma, each electron has to generate enough secondary emission. Therefore, 0.25 Pa was concluded to be the optimum working pressure for SnO2 sputtering without compromising film quality and device performance.

The impact of flow rate of O2 and Ar during SnO2 sputtering on device performance was also studied. The flow rate of Ar was kept constant at 50 sccm while the flow rate of O2 was varied from 1 sccm, 5 sccm, to 10 sccm (defined as FR1:50, FR5:50, and FR10:50 respectively). Figure 5c shows the J-V characteristics of PSCs with 40 nm SnO2 sputtered under the same working pressure of 0.25 Pa but different flow rates of O2 and Ar. The FR5:50 (O2:Ar) PSC showed a PCE of 12.82% with VOC of 0.965 V, JSC of 22.91 mAcm−2, and FF of 58.0%. Its performance was slightly better that of the FR10:50 PSC. However, the FR1:50 PSC yielded the poorest performance: a PCE of 8.66% with VOC of 0.938 V, JSC of 19.97 mAcm−2, and FF of 46.2%. A possible reason is that too low oxygen flow rate (or partial pressure) does not favor stoichiometric SnO2 sputtering. The fewer O2 amount was not sufficient to compensate and combine with the tin ions sputtered out of the target to form high-quality SnO2 film and hence worsened the hole blocking ability. The performance of devices using SnO2 ETLs with different parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 5d shows the J-V characteristics of the champion PSC using 40 nm SnO2 sputtered under optimized working pressure of 0.25 Pa and 5:50 O2:Ar ratio measured under reverse and forward scanning. It achieved a PCE of 12.82% with a VOC of 0.965 V, a JSC of 22.91 mAcm−2, and an FF of 58.0% when measured under reverse voltage scanning and a PCE of 12.06% with a VOC of 0.931 V, a JSC of 22.63 mAcm−2, and an FF of 57.2% when measured under forward voltage scanning. Therefore, the device exhibits a small hysteresis. In comparison, Fig. 5e shows the J-V characteristics of the champion PSC based on solution-processed SnO2. It achieved a lower PCE of 10.78% with a VOC of 0.901 V, a JSC of 21.75 mAcm−2, and an FF of 54.9% when measured under reverse voltage scanning and a lower PCE of 9.58% with a VOC of 0.891 V, a JSC of 21.54 mAcm−2, and an FF of 49.9% when measured under forward voltage scanning. It exhibited a more significant hysteresis. The external quantum efficiency (EQE) of both champion devices are shown in Fig. 5f.

To investigate the stability, both champion devices were left in room-temperature dry air with 30% humidity in dark for 192 hours. The PCE of each device was measured every 24 hours. It is found after 192 hours that the sputtered SnO2 based champion device could retain over 93% of its initial PCE while the solution-processed SnO2 based champion device could only retain 77% of its initial PCE. Supplementary Fig. S8 shows the J-V characteristics of both devices measured after 192 hours of stability test. The PCE of the sputtered SnO2 based device dropped to 11.91% with a VOC of 0.929 V, a JSC of 21.99 mAcm−2, and an FF of 58.3% while the PCE of the solution-processed SnO2 based device dropped to 8.34% with a VOC of 0.853 V, a JSC of 19.75 mAcm−2, and an FF of 49.5%. Supplementary Fig. S9a shows the evolution of their PCEs throughout the monitored period. The performance loss can be attributed to the degradation of the perovskite film within an unencapsulated device in 65% humidity. The highly hygroscopic and deliquescent properties of Li-TFSI used as dopant in Spiro-OMeTAD can also be regarded as a contribution to perovskite degradation due to penetration of water molecules45. In addition, the perovskite film could deteriorate rapidly in the presence of TBP as a polar solvent. Therefore, TBP may be a good solvent for perovskite, which means it can corrode the perovskite layer46. It is worth mentioning that the perovskite films, HTL films, and all devices were annealed, prepared, unencapsulated, and characterized in ambient condition with humidity greater than 65%. It convinces the viability of air processability of perovskite films, HTL films, and device characterization without the use of a glove box. To further illustrate this assertion, 40 sputtered SnO2 based PSCs in one single batch using the optimized SnO2 parameters and 40 solution-processed SnO2 based PSCs in one batch were fabricated by the same procedures. Statistics as shown in Supplementary Fig. S9b convince the reproducibility and consistency of device performance. Both batches of devices demonstrated normal distribution of PCEs. It can be concluded that sputtered SnO2 based devices showed higher average PCE and sputtered SnO2 is therefore more effective and beneficial to enhance PSC device performance and stability.

Flexibility is a desirable feature of thin film solar cells for a variety of applications, such as portable power sources, building-integrated photovoltaics, clothing and textiles, power-generating fabrics, and electronics with light-weight curved surface. One of the main advantages in the use of sputtered SnO2 is that no sintering or annealing step is required thus flexible plastic substrates can be used. The other major fabrication steps (vapor deposition of perovskite, spin-coating of Spiro-OMeTAD, and thermal evaporation of Au) are also carried out in room temperature condition, which means this fabrication process as a whole is compatible with flexible substrates. To date, majority of the reported flexible PSCs employ spin-coated TiO2, ZnO, or PCBM as ETL47,48,49,50,51, while very few of them used solution-processed SnO2 as ETL. To illustrate the compatibility of sputtered SnO2 with flexible substrates for perovskite photovoltaic, in our work rigid FTO glass substrate was therefore replaced by flexible substrate, namely indium-doped-tin-oxide-coated polyethylene naphthalate (ITO-PEN) (Fig. 6a). Supplementary Fig. S10a shows the XRD spectrum of vapor-deposited perovskite grown on flexible ITO-PEN. It presented an expected perovskite spectrum with sharp signal intensities and without PbI2 residue, showing that vapor deposition and post-annealing treatment of perovskite on flexible substrates did not induce any perovskite degradation. 20 devices were fabricated using the same preparation procedures and their PCE distribution is summarized in Supplementary Fig. S10b. Figure 6b shows the J-V characteristics of the champion device on flexible ITO substrate. It yielded a PCE of 5.88% with a VOC of 0.932 V, a JSC of 8.91 mAcm−2, and an FF of 70.8% when measured under reverse voltage scanning and a PCE of 5.48% with a VOC of 0.898 V, a JSC of 8.71 mAcm−2, and an FF of 70.1% when measured under forward voltage scanning. Therefore, the device exhibits a small hysteresis. The discrepancies between JSC’s appeared in the studied devices measured under reverse and forward scannings might be the result of slow response of photocurrent and higher defect density52. It has been confirmed that higher defect density significantly contributes to the J-V hysteresis and degradation of photovoltaic parameters52,53. In comparison with the champion device based on rigid FTO glass substrate, the flexible devices yielded a substantial loss in JSC but a significant improvement in FF. The loss of JSC could be accounted to the lower transmittance through ITO-PEN substrates compared to FTO glass substrates and the threefold increase in device area from 3.14 mm2 to 10 mm2. On the other hand, the improvement in FF could be caused by the smoother ITO electrode surface, allowing flatter coverage of SnO2 film and eventually more compact interface between SnO2 film and perovskite for even more effective electron extraction and reduced series resistance.

Photograph and device performance of a perovskite solar cell prepared on a flexible PEN substrate. (a) Photograph of PSCs prepared on a flexible ITO-PEN substrate. (b) J-V characteristics of the champion perovskite solar cell measured under reverse and forward voltage scanning with AM1.5G illumination. (c) Normalized PCE (measured on a flat surface) after bending the substrate with decreasing radii of curvature R. All measurements were performed on a single device from the highest radius of curvature to the lowest. The linear fit is provided as a guide to the eye. (d) Normalized PCE of a flexible PSC as a function of bending cycles at a radius of 2 cm.

Mechanical flexibility of devices under bending stress is of great importance concerning flexible and/or wearable device applications. Bending tests showed how well the device performance retained after being bent repeatedly to decreasing radii of curvature. The identical flexible PSC was bent by mechanical force with 10 different radii of curvature in one bending cycle. After each round of bending, the device performance was measured repetitively. The impact of bending on device PCE is presented in Fig. 6c. Less than 12% drop in PCE was observed. This result indicated sputtered SnO2 film is an effective and robust ETL for flexible PSC application. The impact of mechanical bending via multiple cycles of bending test was further evaluated. A total of 100 consecutive bending cycles at radius of 2 cm were performed. As shown in Fig. 6d, the device sustained over 90% of its initial PCE. After the bending test, VOC, JSC, and FF of the flexible device respectively dropped from 0.930 V to 0.929 V, from 8.76 mAcm−2 to 8.72 mAcm−2, and from 71.4% to 70.3%. Consequently, the PCE reduced from 5.82% to 5.69%. Although the flexible devices based on sputtered SnO2 demonstrated lower PCE than devices based on TiO2, ZnO, and PCBM, this is a pioneering work proving that sputtered SnO2 is effective and robust on both rigid and flexible substrates for perovskite photovoltaics. Sputtering technique is desirable for upscaling device area with uniform film deposition while flexible devices are especially attractive for a variety of consumer-driven products.

Conclusion

We have pioneered the optimization and implementation of radio frequency magnetron sputtered SnO2 as electron transport layer for vapor-deposited-MAPbI3-based perovskite solar cells on both rigid and flexible substrates. It was demonstrated that neither mesoporous scaffold nor any high-temperature processing procedures were required to achieve efficient and air-stable devices without the use of a glove box. It is noteworthy that in the current device structure there was no backside passivation and all devices were not packaged, so the entire fabrication and characterization processes were subject to ambient condition of humidity greater than 65%. Despite the air processing in humid environment and perovskite annealing on flexible substrates, PSCs of 12.82% PCE on rigid glass substrates and 5.88% PCE on flexible substrates were achieved. We have also shown that the viability and repeatability of acquiring high-quality vapor-deposited perovskite films with large grain sizes and smooth morphology on sputtered SnO2 film via short-time annealing at elevated temperature processing in ambient condition, proving its compatibility with vapor-deposited perovskite films. More importantly, sputtered SnO2 based devices were demonstrated to have better device photovoltaic performance and stability than solution-processed SnO2 based devices. Such successful implementation of robust sputtered SnO2 films on flexible devices could serve as a promising route for future development and application of sputtered SnO2 film into large-scale cost-effective all-vacuum-deposited flexible perovskite photovoltaics.

Methods

Materials

FTO-coated glass substrates were purchased from Zhuhai Kaivo Optoelectronic Technology Co., Ltd. ITO-coated flexible PEN substrates were purchased from Peccell Technologies, Inc. The SnO2 target of 2-inch diameter was purchased from Chinese Rare Metal Co. Ltd. CH3NH3I (MAI) was purchased from Dyesol. PbI2, bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide lithium salt (Li-TFSI), 4-tert-Butylpyridine (TBP), and chlorobenzene were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. N2,N2,N2′,N2′,N7,N7,N7′,N7′-octakis(4-methoxyphenyl)-9,9′-spirobi[9H-fluorene]-2,2′,7,7′-tetramine (Spiro-OMeTAD) was purchased from Lumtec. All materials were used as received.

Device fabrication

The substrates were sequentially washed with acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water. The sheet resistance of FTO is 15 Ω □−1 and the thickness of glass and FTO are 1.6 mm and 420 nm respectively. The average transmittance of FTO glass in the visible region is 85%. The ITO-PEN has a sheet resistance of 15 Ω □−1, a thickness of 0.125 mm, and 78% transmittance in the visible region. SnO2 was deposited on FTO glass and ITO-PEN by radio frequency magnetron sputtering in room temperature. The clean substrates were transferred to a vacuum chamber and evacuated to a pressure of 4 × 10−4 Pa for SnO2 sputtering. The substrates were mounted on a rotating platform, 10 cm above the SnO2 target (China Rare Metal Co. Ltd.). The sputtering atmosphere was consisted of O2 and Ar. When 4 × 10−4 Pa was reached, O2 (99.99%) and Ar (99.99%) were pumped into the chamber. The gas flow rates of O2 and Ar were controlled by gas-flow meters and the gas flow ratio of O2 and Ar was set 1 sccm and 50 sccm, 5 sccm and 50 sccm, or 10 sccm and 50 sccm respectively. The working pressure for sputtering was maintained 0.25 Pa, 0.5 Pa, or 1.0 Pa. The SnO2 target was sputtered with a sputtering power of 60 W. The sputtered SnO2 thickness was set as 20 nm, 40 nm, 60 nm, or 80 nm at a deposition rate of 0.43 Å s−1. Solution-processed SnO2 films were prepared by spin-coating 0.1 M precursor solution of SnCl2 · 2H2O in ethanol at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds on clean FTO substrates. The SnO2 thin films were finally heated in air at 180 °C for 1 hour. The MAPbI3 perovskite was fabricated by a 2-step vapor deposition. The vapor deposition rate was controlled using a quartz sensor and calibrated after measuring the thickness of PbI2 and MAI films. The sources were located at the bottom of the chamber with an angle of 90° with respect to the SnO2-coated substrates. The distance between source and substrate was 20 cm. The evaporation rate of both PbI2 and MAI was maintained in a range of 1.5–2.0 Å s−1. 120 nm PbI2 and 280 nm MAI were evaporated to generate a resultant 400 nm MAPbI3 film. The as-deposited films were annealed at 130 °C for 10 minutes in ambient condition of 65% humidity. The perovskite films were then covered by Spiro-OMeTAD, which composed of 80 mgmL−1 chlorobenzene, 17.5 μL Li-TFSI (520 mgmL−1 acetonitrile), and 28.5 μL TBP, was spin-coated at 3000 rpm for 30 s. The films were left in a desiccator overnight. To complete the devices, 100 nm gold was deposited by thermal evaporation at 1 Å s−1 as an electrode. The device area on FTO glass and ITO-PEN were 0.0314 cm2 and 0.1 cm2, respectively.

Device measurements

The AM1.5G solar spectrum was simulated by an Abet Class AAB Sun 2000 simulator with an intensity of 100 mWcm−2 calibrated with a KG5-filtered Si reference cell. The current-voltage (I–V) data were measured using a 2400 series sourcemeter (Keithley, USA). I–V sweeps (forward and reverse) were performed between −1.2 and +1.2 V, with a step size of 0.02 V and a delay time of 100 ms at each point.

Material characterization

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (JEOL JSM-7100F) and X-ray diffraction method (Bruker D8 X-ray diffractometer, USA) utilizing Cu K α radiation were used to study the thickness, morphology, roughness of the films, and phase characterization. The optical absorption and steady-state photoluminescence spectra were recorded on a Lambda 20 spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, USA) and InVia (Renishaw) micro raman/photoluminescence system, respectively. Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (Axis Ultra DLD) was used to determine the valence band maximum of SnO2 films. Scanning probe microscopy (NanoScope III) (Digital Instruments) was used to characterize the surface roughness of films.

References

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6050–6051 (2009).

Green, M. A. et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 51). Prog Photovolt Res Appl 26, 3–12 (2018).

Xiao, J. et al. The emergence of the mixed perovskites and their applications as solar cells. Advanced Energy Materials (2017).

Zhou, H. et al. Photovoltaics. Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 345, 542–546 (2014).

Liu, M., Johnston, M. B. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells by vapour deposition. Nature 501, 395 (2013).

Burschka, J. et al. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 499, 316 (2013).

Jeon, N. J. et al. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nature materials 13, 897 (2014).

Eperon, G. E., Burlakov, V. M., Docampo, P., Goriely, A. & Snaith, H. J. Morphological control for high performance, solution‐processed planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. Advanced Functional Materials 24, 151–157 (2014).

Ke, W. et al. Perovskite solar cell with an efficient TiO2 compact film. ACS applied materials & interfaces 6, 15959–15965 (2014).

You, J. et al. Improved air stability of perovskite solar cells via solution-processed metal oxide transport layers. Nature nanotechnology 11, 75 (2016).

Tang, K. C., You, P. & Yan, F. Highly Stable All‐Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells Processed at Low Temperature. Solar RRL, 1800075 (2018).

Tavakoli, M. M. et al. Highly efficient flexible perovskite solar cells with antireflection and self-cleaning nanostructures. ACS nano 9, 10287–10295 (2015).

Tavakoli, M. M. et al. Efficient, flexible and mechanically robust perovskite solar cells on inverted nanocone plastic substrates. Nanoscale 8, 4276–4283 (2016).

Arora, N. et al. Perovskite solar cells with CuSCN hole extraction layers yield stabilized efficiencies greater than 20. Science 358, 768–771 (2017).

Green, M. A., Ho-Baillie, A. & Snaith, H. J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nature Photonics 8, nphoton. 2014.134 (2014).

Yang, G., Tao, H., Qin, P., Ke, W. & Fang, G. Recent progress in electron transport layers for efficient perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 4, 3970–3990 (2016).

Tavakoli, M. M., Zakeeruddin, S. M., Grätzel, M. & Fan, Z. Large‐Grain Tin‐Rich Perovskite Films for Efficient Solar Cells via Metal Alloying Technique. Adv Mater 30, 1705998 (2018).

Zheng, X. et al. Designing nanobowl arrays of mesoporous TiO2 as an alternative electron transporting layer for carbon cathode-based perovskite solar cells. Nanoscale 8, 6393–6402 (2016).

Singh, T. et al. Sulfate‐Assisted Interfacial Engineering for High Yield and Efficiency of Triple Cation Perovskite Solar Cells with Alkali‐Doped TiO2 Electron‐Transporting Layers. Advanced Functional Materials 28, 1706287 (2018).

Leijtens, T. et al. Overcoming ultraviolet light instability of sensitized TiO2 with meso-superstructured organometal tri-halide perovskite solar cells. Nature communications 4, 2885 (2013).

Jiang, Q., Zhang, X. & You, J. SnO2: A Wonderful Electron Transport Layer for Perovskite Solar Cells. Small 14, 1801154 (2018).

Xiong, L. et al. Review on the Application of SnO2 in Perovskite Solar Cells. Advanced Functional Materials 28, 1802757 (2018).

Tiwana, P., Docampo, P., Johnston, M. B., Snaith, H. J. & Herz, L. M. Electron mobility and injection dynamics in mesoporous ZnO, SnO2, and TiO2 films used in dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS nano 5, 5158–5166 (2011).

Song, J. et al. Low-temperature SnO 2-based electron selective contact for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 3, 10837–10844 (2015).

Zhu, Z. et al. Enhanced Efficiency and Stability of Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells Using Highly Crystalline SnO2 Nanocrystals as the Robust Electron‐Transporting Layer. Adv Mater 28, 6478–6484 (2016).

Xiong, L. et al. Performance enhancement of high temperature SnO 2-based planar perovskite solar cells: electrical characterization and understanding of the mechanism. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 4, 8374–8383 (2016).

Lee, Y. et al. Enhanced charge collection with passivation of the tin oxide layer in planar perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 5, 12729–12734 (2017).

Jung, K., Seo, J., Lee, S., Shin, H. & Park, N. Solution-processed SnO2 thin film for a hysteresis-free planar perovskite solar cell with a power conversion efficiency of 19.2%. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 5, 24790–24803 (2017).

Mali, S. S., Patil, J. V., Kim, H. & Hong, C. K. Synthesis of SnO2 nanofibers and nanobelts electron transporting layer for efficient perovskite solar cells. Nanoscale 10, 8275–8284 (2018).

Jiang, Q. et al. Enhanced electron extraction using SnO2 for high-efficiency planar-structure HC (NH 2) 2 PbI 3-based perovskite solar cells. Nature Energy 2, 16177 (2017).

Lee, Y. et al. Efficient Planar Perovskite Solar Cells Using Passivated Tin Oxide as an Electron Transport Layer. Advanced Science, 1800130 (2018).

Baena, J. P. C. et al. Highly efficient planar perovskite solar cells through band alignment engineering. Energy & Environmental Science 8, 2928–2934 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Low-temperature plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of tin oxide electron selective layers for highly efficient planar perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 4, 12080–12087 (2016).

Dong, Q. et al. Insight into perovskite solar cells based on SnO2 compact electron-selective layer. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 119, 10212–10217 (2015).

Anaraki, E. H. et al. Highly efficient and stable planar perovskite solar cells by solution-processed tin oxide. Energy & Environmental Science 9, 3128–3134 (2016).

Wu, W., Chen, D., Cheng, Y. & Caruso, R. A. Thin Films of Tin Oxide Nanosheets Used as the Electron Transporting Layer for Improved Performance and Ambient Stability of Perovskite Photovoltaics. Solar RRL 1 (2017).

Ko, Y. et al. Electrodeposition of SnO2 on FTO and its Application in Planar Heterojunction Perovskite Solar Cells as an Electron Transport Layer. Nanoscale research letters 12, 498 (2017).

Tao, H. et al. Room-temperature processed tin oxide thin film as effective hole blocking layer for planar perovskite solar cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 434, 1336–1343 (2018).

Singh, T. & Miyasaka, T. Stabilizing the efficiency beyond 20% with a mixed cation perovskite solar cell fabricated in ambient air under controlled humidity. Advanced Energy Materials 8, 1700677 (2018).

Ke, W. et al. Low-temperature solution-processed tin oxide as an alternative electron transporting layer for efficient perovskite solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6730–6733 (2015).

Yu, H. et al. Superfast Room‐Temperature Activation of SnO2 Thin Films via Atmospheric Plasma Oxidation and their Application in Planar Perovskite Photovoltaics. Adv Mater. (2018).

You, J. et al. Moisture assisted perovskite film growth for high performance solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 183902 (2014).

Kim, M. et al. High-Temperature–Short-Time Annealing Process for High-Performance Large-Area Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS nano 11, 6057–6064 (2017).

Kakavelakis, G. et al. Extending the Continuous Operating Lifetime of Perovskite Solar Cells with a Molybdenum Disulfide Hole Extraction Interlayer. Advanced Energy Materials 8, 1702287 (2018).

Lee, I., Yun, J. H., Son, H. J. & Kim, T. Accelerated degradation due to weakened adhesion from Li-TFSI additives in perovskite solar cells. ACS applied materials & interfaces 9, 7029–7035 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Montmorillonite as bifunctional buffer layer material for hybrid perovskite solar cells with protection from corrosion and retarding recombination. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2, 13587–13592 (2014).

Liu, D. & Kelly, T. L. Perovskite solar cells with a planar heterojunction structure prepared using room-temperature solution processing techniques. Nature photonics 8, 133 (2014).

Ameen, S., Akhtar, M. S., Seo, H., Nazeeruddin, M. K. & Shin, H. An insight into atmospheric plasma jet modified ZnO quantum dots thin film for flexible perovskite solar cell: optoelectronic transient and charge trapping studies. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 119, 10379–10390 (2015).

Docampo, P., Ball, J. M., Darwich, M., Eperon, G. E. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient organometal trihalide perovskite planar-heterojunction solar cells on flexible polymer substrates. Nature communications 4, 2761 (2013).

Schmidt, T. M., Larsen‐Olsen, T. T., Carlé, J. E., Angmo, D. & Krebs, F. C. Upscaling of perovskite solar cells: fully ambient roll processing of flexible perovskite solar cells with printed back electrodes. Advanced Energy Materials 5 (2015).

Kakavelakis, G. et al. Efficient and highly air stable planar inverted Perovskite solar cells with reduced Graphene oxide doped PCBM electron transporting layer. Advanced Energy Materials 7, 1602120 (2017).

Lee, J. et al. The interplay between trap density and hysteresis in planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. Nano letters 17, 4270–4276 (2017).

Son, D. et al. Universal Approach toward Hysteresis-Free Perovskite Solar Cell via Defect Engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1358–1364 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 51672231), Shen Zhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (Project No. JCYJ20170818114107730) and Hong Kong Research Grant Council (General Research Fund Project No. 16237816). The authors also acknowledge the support from the Center for 1D/2D Quantum Materials and the State Key Laboratory on Advanced Displays and Optoelectronics at HKUST.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. and Z.F. designed the experiments. M.K., Q.Z., D.Z. and Z.F. carried out experiments. M.K., Q.Z., D.Z. and Z.F. contributed to the data analysis. M.K., Q.Z. and Z.F. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kam, M., Zhang, Q., Zhang, D. et al. Room-Temperature Sputtered SnO2 as Robust Electron Transport Layer for Air-Stable and Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells on Rigid and Flexible Substrates. Sci Rep 9, 6963 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42962-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42962-9

This article is cited by

-

Moderate temperature deposition of RF magnetron sputtered SnO2-based electron transporting layer for triple cation perovskite solar cells

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Efficient perovskite solar cells via improved carrier management

Nature (2021)

-

RETRACTED ARTICLE: Investigating the sensing properties of SnO2 nanoparticles doped with gold

Applied Physics A (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.