Abstract

Stochastic perturbations can trigger major ecosystem shifts. Marine systems have been severely affected in recent years by mass mortality events related to positive thermal anomalies. Although the immediate effects in the species demography affected by mortality events are well known, information on the mid- to long-term effects at the community level is much less documented. Here, we show how an extreme warming event replaces a structurally complex habitat, dominated by long-lived species, by a simplified habitat (lower species diversity and richness) dominated by turf-forming species. On the basis of a study involving the experimental manipulation of the presence of the gorgonian Paramuricea clavata, we observed that its presence mitigated the effects of warming by maintaining the original assemblage dominated by macroinvertebrates and delaying the proliferation and spread of the invasive alga Caulerpa cylindracea. However, due to the increase of sediment and turf-forming species after the mortality event we hypothesize a further degradation of the whole assemblage as both factors decrease the recruitment of P.clavata, decrease the survival of encrusting coralligenous-dwelling macroinvertebrates and facilitate the spreading of C. cylindracea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is impairing ecosystems around the world by affecting the phenology, physiology and ecological interactions of key species, triggering shifts in their distributions, and modifying community composition, structure and dynamics1,2,3. In addition to warming, another consequence of climate change is an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme climatic events, such as stochastic infrequent perturbations4,5,6 that can drive ecosystem shifts7,8. In fact, extreme climatic events are reported to represent greater impacts on natural ecosystems than the progressive temperature increase derived from global warming9,10. In comparison to terrestrial ecosystems, where the negative effects of extreme events have been widely documented11,12, the responses of marine ecosystems to these events are far less reported and are more poorly understood (but see7,8,13,14).

Positive thermal anomalies are likely the major extreme climatic events in marine and oceanic ecosystems15. Mass mortality episodes and diseases linked to thermal anomalies have increased during the last few decades16,17. However, to date, mass mortality events have only been documented at the species and population levels, especially in engineering species, such as hard corals, gorgonians and sponges18,19,20,21. The delayed direct and indirect (e.g. through engineering species loss) effects of thermal anomalies at the community level are much less studied7,8,14. Moreover, engineering species loss is blamed to facilitate invasions15,22,23, which can be fostered if the whole assemblage is affected by thermal stress.

The unpredictability of the occurrence of thermal anomalies and the inherent complexity of in situ manipulative experiments have hampered studies on the role of engineering species in protecting entire assemblages from warming events as well as on the evaluation of their contribution (direct and indirect) to reduce the effects (if any) of thermal anomalies at the community level.

The northwestern Mediterranean Sea has been severely affected by mass mortality events of several benthic invertebrates coupled with high-temperature conditions in recent decades21,24,25,26,27,28,29. Additionally, the Mediterranean Sea is especially prone to marine invasions30, being one of the most affected areas by the spread of invasive species worldwide31,32. One of the Mediterranean habitats most disturbed by both thermal anomalies and invasive species are coralligenous outcrops22,26,33,34. Coralligenous assemblages represent highly diverse and structurally complex habitats unique to the Mediterranean Sea33. The engineering species that compose this habitat show slow growth and low recruitment rates, which results in a high vulnerability to strong disturbances35,36,37,38. The red gorgonian Paramuricea clavata (Riso, 1826), is one of the most paradigmatic engineering species thriving in coralligenous outcrops33. This species can be severely affected by thermal anomalies10, with mortalities that can reach up to 80% of the colonies21, and by invasive algae that strongly limit their recovery22.

In this study, we take advantage of a five-year (2009–2014) monitoring study on a coralligenous assemblage unexpectedly affected by an episode of anomalous high temperatures in the Archipelago of Cabrera National Park (2011; Fig. 1). This monitoring, was combined with an experimental study, at the same location (Fig. 2), manipulating the presence of the red gorgonian P. clavata, to assess (1) the effects of the thermal anomaly at the community level, (2) the structural role of P. clavata in coralligenous habitats and (3) how the presence or absence of P. clavata may influence the resistance of the assemblage to the effects of a thermal anomaly and to the invasion by the alien alga Caulerpa cylindracea.

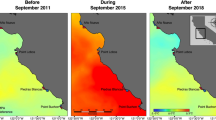

(A–E) Stratification temperature maps showing the inter-annual variability of the temperature at the study site for the years 2009 to 2013. A grey band is overlaid on the target coralligenous assemblage depth. (F) Total time (represented in days) per year that temperature at 40 m depth exceeds the different temperature thresholds.

Graphical scheme of the sampling methodology for the two approaches conducted at the study site: (i) the observational study to evaluate the effects of the thermal anomaly on the whole community, and (ii) the experimental study to test the role of the P. clavata as a structural species. Thermal anomaly is also represented in the scheme to graphically represent the entire study context.

Results

2009–2013 temperature and 2011 thermal anomaly

In situ temperature data showed that the extent of warm temperature exposure (>20 °C) at 40 m depth in 2011 (79 days) was much more prolonged (228%) than the mean value observed for the rest of the years (35 ± 16 days; MEAN ± SD; Fig. 1F). It was noticeable, that the exposure to the 24 °C lethal threshold in 2011 (17 days) represented a 2187% increase with respect to the mean value observed the other 4 years (0,8 days) highlighting a strong positive thermal anomaly in 2011 (Fig. 1F).

Monitoring study to evaluate the effects of a thermal anomaly on coralligenous assemblages

A total of 72 taxa were identified across years at several taxonomic levels, 7 phyla, 20 genera and 45 species. From them, 17 taxa were macroalgae, 9 anthozoans, 2 hydrozoans, 14 bryozoans, 1 polychaete, 1 foraminifera, 21 sponges and 7 tunicates. A total of 59 species were identified on the assemblage on 2009, 53 on 2012 and 31 on 2014 (Supplementary Table S1).

The species composition changed significantly with time (Fig. 3; p < 0.01, Supplementary Table S2). The main species contributing to the coralligenous assemblages were the encrusting algae Mesophyllum sp., Peyssonnelia spp. and Palmophyllum crassum; the sponges Phorbas topsenti, Axinella damicornis and Crambe crambe; the bryozoans Scrupocellaria spp. and Schizomavella mamillata; the tunicate Pseudosistoma cyrnusense; and two arbitrarily fixed categories: “turf” (consisting of small invertebrates and algae) and detritus (SIMPER analysis; Supplementary Table S3A). However, abundance of most species increased or decreased after the thermal anomaly (Supplementary Table S3B). For instance, the encrusting algae Peyssonnelia spp. increased (23%) its abundance while Mesophyllum sp. decreased (56%). The most representative sponge species (A. damicornis and C. crambe, 56% and 63% respectively), the tunicate P. cyrnusense (100%), the bryozoan S. mamillata (72%), and the cnidarian Alcyonium acaule (100%) decreased their abundance after the thermal anomaly, whereas “turf” and “detritus” categories increased during the last study years (100% and 127% respectively; Supplementary Table S3B). Finally, erect algae such as Dictyopteris sp. and Carpomitra costata, and bryozoans such as Savignyella lafontii increased (535%, 1733% and 1955% respectively) their abundance the last monitoring year (S3. B).

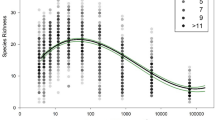

In terms of diversity, the assemblage remained stable before and just after the thermal anomaly (Fig. 4; p > 0.05; Supplementary Table S4). However, species richness and Shannon’s index decreased significantly in 2014, three years after the thermal anomaly (Fig. 4; p < 0.05, Supplementary Table S4).

Box plot of the temporal variation of (A) species richness, (B) Shannon’s diversity index and (C) evenness. The median values (bold horizontal line), the interquartile distances (the box) and the extreme values, which are non-outliers (whiskers), are indicated in the plot. Significant differences between years (p-values of Tukey test with 95% confidence intervals) are indicated above boxes with letters.

Manipulative field experiment to assess the structural role of P. clavata and the resistance of the understory assemblage to the impacts of the thermal anomaly and invasive species

Species composition and abundances significantly changed among treatments and through time in the manipulative experiment, whereas the interaction between treatment and time was not significant (Table 1).

Principal Coordinate Ordination analysis (PCOs) shows shifts in the understory during the experiment (Fig. 5) both if we take into account species presence/absence or the abundances. The first axis in both PCOs is associated with time, being 2009 and 2012 (just after the thermal anomaly) similar among them, and different from 2014. SIMPER analysis (Supplementary Table S5) reveals that the significant changes through time were primarily related to a decrease in abundance of several erect invertebrates such as the tunicates P. cyrnusense and Aplidium sp., cnidarians A. acaule and Leptopsammia pruvoti, bryozoan S. linearis and some sponges (A. damicornis and C. crambe), as well as to the increase in abundance of some erect algae such as C. cylindracea and Dictyopteris sp.

Principal coordinate analysis of (A) abundance species data and (B) presence-absence species data showing the shift in the community for the different treatments. Distances in ordination represent differences in assemblage composition, and the overlay vectors represent the most correlated species (>0.80). In the legend, GOR indicates non-manipulated plots with a natural gorgonian density, ABS non-manipulated plots where gorgonians were naturally absent and REM manipulated plots from which gorgonians were totally removed.

The second axis of the PCO is strongly correlated with the treatment factor showing that the understory assemblage is affected by gorgonian presence. PERMANOVA pairwise test (Table 2) shows that the abundance and the presence/absence of understory species in 2009 were similar in GOR and REM plots (p > 0.05), when REM still had a natural canopy of gorgonians, while ABS plots (naturally without gorgonians) differed significantly from GOR and REM plots (p < 0.05).

GOR and REM plots were characterized by a major contribution of the alga P. crassum, the sponges C. crambe and Pleraplysilla spinifera, the tunicate P. cyrnusense, the anthozoans L. pruvoti and A. acaule, and the bryozoans S. linearis and Reteporella sp. In contrast, the algae Peyssonnelia spp., Halopteris filicina, Dictyopteris sp. and Dictyota sp., the sponge A. damicornis, and “detritus” category contributed more to the coverage of ABS plots (Supplementary Table S6).

After the thermal anomaly (2012) all treatments were significantly different from each other, while at the end of the experiment (2014) the understory of REM and ABS plots (both now without gorgonians) became similar (p > 0.05; Table 2) and significantly different (p < 0.05) from GOR plots (with gorgonians). In 2014, all treatment plots were characterized by a high abundance of turf, the alga Mesophyllum sp. and the sponge P. topsenti. However, GOR plots displayed higher abundances of macroinvertebrates such as L. pruvoti, C. crambe, P. cyrnusense and S. mamillata, and lower abundances of algae C. cylindracea, Dictyopteris sp., H. filicina, Peyssonnelia spp., and sponge A. damicornis, than the REM and ABS plots (Supplementary Table S7). Therefore, in general, the presence of gorgonians (GOR) favored macroinvertebrates in contrast to algae.

Time and treatment had a significant effect on C. cylindracea abundance (Supplementary Table S8). However, the significant interaction between both factors indicates that the C. cylindracea increase with time was dependent on the presence of gorgonians. All treatments exhibited a pattern of C. cylindracea increase over time but its abundance on ABS plots was always higher, increasing from 2009 to 2012 (p < 0.05; Fig. 6) and from 2012 to 2014 (p < 0.05; Fig. 6). After the removal of gorgonians (REM treatment) C. cylindracea also significantly increased from 2012 to 2014 (p < 0.05; Fig. 6). In contrast, there was not a significant increase of C. cylindracea in GOR plots between 2012 and 2014 (p > 0.05; Fig. 6).

Representation of the mean values of the percentage abundance of C. cylindracea for each treatment and year with standard error bars. Significant differences between factors (p-values of pairwise comparisons with 95% confidence intervals) are indicated above bars with letters. In the legend, GOR indicates non-manipulated plots with a natural gorgonian density, ABS non-manipulated plots where gorgonians were naturally absent and REM manipulated plots from which gorgonians were totally removed.

Species richness experimented a significant decrease along the experiment in the three treatments (Fig. 7A; Supplementary Table S9), but no variation with time was detected in the Shannon’s diversity and evenness indices in any treatment (Fig. 7B,C; Supplementary Table S9).

Box plots of the temporal variation of (A) species richness, (B) Shannon’s index diversity and (C) evenness for each treatment. The median values (bold horizontal line, the interquartile distances (the box), the extreme values, which are non-outliers (whiskers), and the outliers (spots) are indicated in the plot. Significant differences between factors (Year and Treatment, p-values of pairwise comparisons with 95% confidence intervals) are indicated above boxes with letters. In the legend, GOR indicates non-manipulated plots with a natural gorgonian density, ABS non-manipulated plots where gorgonians were naturally absent and REM manipulated plots from which gorgonians were totally removed.

Discussion

Paramuricea clavata mortalities have been exclusively attributed to temperature anomalies and diver frequentation33. Considering the low anthropogenic pressures and the lack of diving activities in the study site, we pose that temperature anomaly is the most probable cause that explains P. clavata mortalities at the study site. In fact, temperature during summer 2011 was exceptionally higher (Fig. 1), exceeding 24 °C during 17 days at the study depth, which is enough to trigger a mortality event in P.clavata21,24,39,40,41,42. In fact, Linares et al. (2017)43 report a severe affectation of this temperature anomaly on the population of P. clavata at the study site. The understory assemblage also showed effects of this anomaly. However, we show that the delayed (2.5 years) effects were more severe and had far-reaching implications than the immediate effects, which highlights the relevance of examining the effects of climatic driven events in benthic assemblages at different time scales27. The assemblage shifted from being dominated by erect invertebrates and encrusting sponges to be dominated by erect algae and turf-forming species. Several macroinvertebrates and coralline algae usually dwelling in the understory of P. clavata have been reported to be affected by thermal anomalies21,24,44,45,46,47,48,49 and thus, the changes observed in the whole assemblage were expected. Although the fine-tuning mechanisms behind the impacts of a thermal anomaly are difficult to ascertain, it has been reported that many organisms inhabiting coralligenous assemblages suffer from partial mortality or physiological stress41,50,51,52, which may led to their total mortality in subsequent years26. The final result has been a simplification in terms of biodiversity and structure, with losers (e.g. species that are sensitive to thermal stress such as macroinvertebrates) and winners (species that can outcompete the sensitive species and are resistant to thermal anomalies such as turf-forming species).

Moreover, calcareous matrix coming from dead organisms led to an increase of detritus after the thermal anomaly. Detritus accumulate as sediment above the substrate which has a direct deleterious effects on coralligenous outcrops by inhibiting recruitment and promoting burial and scouring of macroinvertebrates53,54,55,56. In turn, heavy sedimentation also facilitates turf growth55,57, which inhibits the recruitment and increases the mortality of juvenile gorgonians and corals23,58,59,60 as well as decreases the reproductive output of several sponges61. The higher abundance of turf-forming species is also probably behind the increase of C. cylindracea, as this species is facilitated by the abundance of turf-forming species62. Cumulative impacts of warming, sedimentation, turf algae overgrowth and invasions may drive a snow-ball effect, speeding up the mid-term shift in the understory assemblage.

The significant effects of the presence/absence of P. clavata on the understory species clearly reveals the role of P. clavata as a habitat forming species, favoring diversity and structure of the understory. Promoting invertebrate settlement and preventing turf growth appear not to be limited to gorgonian forests63,64,65,66,67,68, as it has also been reported for other habitat-forming species such as kelps, which facilitate settlement of sponges and coralline algae and inhibit the presence of turf-forming algae69,70.

Paramuricea clavata has also a mitigation effect of warming temperatures over invertebrates thriving on the understory, although the influence of the thermal anomaly is also noteworthy. In fact, detritus and turf even increased in the presence of Paramuricea, what may compromise the survival of the remaining macroinvertebrates in the long-term.

Finally, although P. clavata does not prevent the establishment of C. cylindracea, it is able to delay its proliferation and spread, probably because complexity of substrata (enhanced by gorgonians presence) is a key factor to limit colonization and spread of C. cylindracea in Mediterranean habitats62,71. Thus, we hypothesize that extreme climatic events may be indirectly promoting the invasion of C. cylindracea in coralligenous assemblages by directly causing the mass mortality of structural native species and by indirectly increasing the abundance of turf-forming species. Moreover, the interaction of various stressors, such as warming and invasive species, may cause additive effects that end up in catastrophic ecosystem changes15,72.

Ongoing environmental changes are predicted to increase the frequency and intensity of extreme climatic events73,74. Here, we show how an extreme warming event can replace a structurally complex habitat dominated by long-lived gorgonians by a simplified habitat dominated by turf-forming species, with a generalized vulnerability to be colonized by invasive species. Thus, we bring evidence of the synergic and additive effects of global (e.g. warming) and local stressors (e.g. invasions) that are affecting ecosystems around the world15,75. Bearing in mind that climatic models predict that the Mediterranean Sea will be one of the regions most affected by warming and extreme climatic events76, our study is especially relevant as it shows a degradation of an entire Mediterranean assemblage to levels never reported before. Whether this process is generally applicable to other assemblages or ecosystems is still unknown, but if these shifts at the ecosystem level regularly occur, the impoverishment of the ecological quality of Mediterranean benthic assemblages, driven by climate change, can happen at stronger and faster rates than assumed.

Methods

Study site

The study site is located in Cabrera National Park (Balearic Islands, western Mediterranean), a remote access area, far away from the coast. In Cabrera NP dissolved inorganic nutrients (DIN), Chla and trace metals are characteristic of oligotrophic Mediterranean waters77,78. Ecological Quality Ratio for all bioindicators (macroalgae, Posidonia oceanica, phytoplankton) and physicochemical parameters evaluated following European Water Framework Directive (WFD, 2000/60/EC) are always above 0.9 units, being 1 the value corresponding to the highest ecological status79,80. In Cabrera NP there is no potential sources of pollution (i.e. industrial, agricultural, dumping, mining or dredging), and human density is 0.9 persons·km−2. There are no rivers or industry. The water is extraordinarily clear: Secchi Disk depth oscillates between 24 m (February) and 38 m (August), whereas the mean annual light extinction coefficient (k) is 0.063 m−1 81. Water temperatures are characteristic of those reported for the Balearic basin, with minimal temperatures around 14 °C and surface temperatures reaching values of 27 °C77,81. Salinity is almost constant in the Mediterranean Sea and ranges in the area from 37.5% to 38.1%77. No significant acidification has been reported in the area.

The studied assemblage was located on a vertical rocky wall between 40 and 45 m depth, facing southeast at the Imperial Islet (39° 07′34″N; 2°57′29″E)82, where diving is completely forbidden, except for scientific purposes.This area suffered the effects of positive thermal anomalies, which mainly affected sublittoral assemblages from 5 to 45 m depth28,43. These anomalous high-temperature conditions were identified as the primary causal factor for the mass mortalities of two abundant invertebrates, the sponge Sarcotragus fasciculatus and the gorgonian P. clavata28,43. Specifically, from 2009 to 2014, two stress factors affected the studied assemblage: (i) a thermal anomaly in 2011, and (ii) the invasion of C. cylindracea, which was first detected in the area in 200883,84.

Monitoring thermal environment

The thermal environment damaged the gorgonian population situated between 37 and 45 m depth affecting 90% of the colonies43. The thermal anomaly was studied by deploying in situ high-resolution (hourly records, ±0.21 °C accuracy) temperature recorders (HOBO Water Temp Pro v2). Temperature loggers were placed at the study site in intervals of 5 m between 5 to 67 m depth and were changed every two years. We used the number of days that the community was exposed to ≥20 °C as a proxy of the extent of warm temperature exposure and, the number of days that the community was exposed to 24 °C as a proxy of the extent of lethal threshold exposure40,41,42 (Fig. 1).

Monitoring study to evaluate the effects of a thermal anomaly on coralligenous assemblages

Photo-quadrats along transects were used to study the changes in species composition and abundances from 2009 to 2014 (Fig. 2). Samplings were performed in May 2009, 2012 and 2014. Periodicity was selected according to the low dynamics and stability of these assemblages (with no temporal changes in biodiversity patterns over more than 5 years38) added to the low accessibility to the study site (at 40–45 m depth in a remote area). Each year, three (2 m-long) transects were randomly deployed between 40 and 45 m depth. Eight photographs of 25 × 25 cm of the understory community were taken per transect as described by Kipson et al. (2011)85. The sampling unit selected (5000 cm2 per transect) was in accordance to the minimal sampling area proposed for coralligenous assemblages dominated by the gorgonian P. clavata57. Pictures were obtained with a Nikon D70S digital SLR camera fitted with a Nikon 20 mm DX lens (3000 * 2000-pixel resolution) and housed in a Subal D70S housing. Lighting was achieved using two electronic strobes fitted with diffusers. Sessile macro-taxa were identified in each picture to the lowest possible taxonomic level, and the abundance of each taxon was measured. Image analysis with Adobe Photoshop software was used to estimate the abundance for each species by means of a superposed reticulum (of 25 × 25 cm, divided in 25 sub-quadrats), and the number of sub-quadrats in which each species appeared was recorded and used as unit of abundance86. Species richness and Shannon’s diversity index were calculated from the data acquired.

Manipulative field experiment to assess the structural role of P. clavata and the resistance of the understory assemblage to the impacts of the thermal anomaly and invasive species

The manipulative experiment was performed at the same coralligenous assemblage than the monitoring study. To assess the role of P. clavata as a structural species and to determine whether its presence can modify the response of the whole assemblage to thermal anomalies, a field experiment manipulating gorgonians presence was conducted from May 2009 to May 2014 at a depth between 40 and 45 m (at the same site than the monitoring; Fig. 2). Three treatments of 20 randomly distributed 25 × 25 cm plots each were set up: a) non-manipulated plots with a natural gorgonian density [approximately 20 colonies/m2 42; GOR], b) non-manipulated plots where gorgonians were naturally absent (ABS), and c) manipulated plots from which gorgonians were totally removed (REM). To minimize possible variation due to local environmental factors, the different replicates of each treatment were located interspaced in an approximately 5 × 20 m area (Fig. 2). To assess species composition and abundances in the different treatments plots over time (before and after the occurrence of the thermal anomaly in 2011), photo sampling was again performed in May 2009, 2012 and 2014. Pictures were analyzed as in the monitoring study. Species richness and Shannon’s diversity index were calculated from the data acquired for each treatment and sampling date.

Statistical analysis

Monitoring study

Shifts in species composition and abundances over time at the assemblage level, were analyzed by non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) based on Bray-Curtis similarity. Data was previously fourth root transformed to mitigate the effects of the most abundant species87 and the most correlated species with the ordination axes (Pearson’s correlation > 0.7) were represented as overlaying vectors. One-way multivariate PERMANOVA (non-parametric analysis of variance) also based on the Bray-Curtis similarity on fourth root transformed data, with year as a fixed factor (3 levels 2009, 2012 and 2014), was performed to analyze species abundance variation through time. Pairwise comparisons were performed to test for differences between years88. Due to the low possible number of permutations (<999), P-values provided by Monte Carlo test were used in preference89. Moreover, SIMPER analyses for the years 2009 and 2014 were performed to identify the species that contributed the most to the assemblage change after the thermal anomaly.

Species richness, Shannon’s diversity and evenness indices were the descriptors used to analyze temporal variations in the target assemblage. One-way ANOVA with year as a fixed factor (three levels: 2009, 2012 and 2014) was performed for each descriptor. Data were previously tested for normal distribution and homogeneity of variances using Shapiro-Wilk normality test and Bartlett’s test respectively (p-values > 0.05). For those variables proving significant in the ANOVA, differences between concrete pairs of years were analyzed by posterior Tukey’s test.

Manipulative experiment

To assess the role of P. clavata as a structural species, we analyzed the effects of its loss on the assemblages subjected to the thermal anomaly. Assemblage composition and structure were analyzed both on species abundance (data previously fourth root transformed) and on presence-absence data with a three-way multivariate PERMANOVA based on the Bray-Curtis similarity, performed with 9999 unrestricted random permutations88. The sampling design included three factors: treatment (as a fixed factor with three levels: GOR, ABS and REM), year (fixed factor with three levels: 2009, 2012 and 2014) and plot (as a random factor, nested in treatment and year). Subsequent pairwise comparisons for all combinations of treatment and year were carried out. To show the temporal trends of the different treatments, a Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCO) based on Bray-Curtis similarity was performed and vectors representing the most correlated species with the ordination axes (Pearson’s correlation > 0.8) were overlaid. P. Paramuricea clavata data was excluded from the analysis, because its presence was manipulated.

Finally, variations in the abundance of the alien alga C. cylindracea, the species richness, Shannon’s and evenness indices of the assemblage, were analyzed along time and between treatments. Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) with three factors (Year and Treatment as fixed factors and Plot as random) were used, as data failed to comply normality assumptions (Saphiro-Wilk test p-value < 0.05), and GLMMs are suitable for non-normal data90 and repeated measures over time91. All analyses were computed using the program Primer 6 + PERMANOVA92,93 and R software94 with Vegan95 and lme496 packages.

Data Availability

Data Availability Statement: The authors agree to archive all data supporting the results of this paper in an appropriate public archive, if it is accepted for publication.

References

Walther, G. et al. Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature 416, 389–395 (2002).

Harley, C. D. G. et al. The impacts of climate change in coastal marine systems. Ecology Letters 9, 228–241 (2006).

Walther, G. Community and ecosystem responses to recent climate change. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 365, 2019–2024 (2010).

Easterling, D. R. Climate extremes: Observations, modeling, and impacts. Science 289, 2068–2074 (2000).

Meehl, G. A. & Tebaldi, C. More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science 305, 994–997 (2004).

Lima, F. P. & Wethey, D. S. Three decades of high-resolution coastal sea surface temperatures reveal more than warming. Nature Communications 3, 704 (2012).

Smale, D. A. & Wernberg, T. Extreme climatic event drives range contraction of a habitat-forming species. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Biological Sciences 280, 20122829 (2013).

Wernberg, T. et al. An extreme climatic event alters marine ecosystem structure in a global biodiversity hotspot. Nature Climate Change 3, 78–82 (2013).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Marine and Freshwater Research 50, 839–866 (1999).

Coma, R. et al. Global warming-enhanced stratification and mass mortality events in the Mediterranean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 6176–6181 (2009).

Parmesan, C. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 37, 637–669 (2006).

Thibault, K. M. & Brown, J. H. Impact of an extreme climatic event on community assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 3410–3415 (2008).

Dayton, P. K. & Tegner, M. J. Catastrophic storms, El Niño, and patch stability in a Southern California kelp community. Science 224, 283–285 (1984).

Wernberg, T. et al. Climate-driven regime shift of a temperate marine ecosystem. Science 353, 169–172 (2016).

Diez, J. M. et al. Will extreme climatic events facilitate biological invasions? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 10, 249–257 (2012).

Harvell, C. D. et al. Emerging marine diseases-climate links and anthropogenic factors. Science 285, 1505–1510 (1999).

Harvell, C. D. Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science 296, 2158–2162 (2002).

Glynn, P. W. & D’Croz, L. Experimental evidence for high temperature stress as the cause of El Niño-coincident coral mortality. Coral Reefs 8, 181–191 (1990).

Oxenford, H. A. et al. Quantitative observations of a major coral bleaching event in Barbados, Southeastern Caribbean. Climatic Change 87, 435–449 (2008).

Cerrano, C. & Bavestrello, G. Mass mortalities and extinctions. Marine Hard Bottom Communities. Patterns, Dynamics, Diversity, and Change. Springer- Verlag, Berlin: Ch. 21. Ecological Studies 206, 297–307 (2009).

Garrabou, J. et al. Mass mortality in Northwestern Mediterranean rocky benthic communities: effects of the 2003 heat wave. Global Change Biology 15, 1090–1103 (2009).

Cebrian, E., Linares, C., Marschal, C. & Garrabou, J. Exploring the effects of invasive algae on the persistence of gorgonian populations. Biological Invasions 14, 2647–2656 (2012).

Linares, C., Cebrian, E. & Coma, R. Effects of turf algae on recruitment and juvenile survival of gorgonian corals. Marine Ecology Progress Series 452, 81–88 (2012).

Cerrano, C. et al. A catastrophic mass-mortality episode of gorgonians and other organisms in the Ligurian Sea (North-western Mediterranean), summer 1999. Ecology Letters 3, 284–293 (2000).

Garrabou, J., Perez, T., Sartoretto, S. & Harmelin, J. G. Mass mortality event in red coral Corallium rubrum populations in the Provence Region (France, NW Mediterranean). Marine Ecology Progress Series 217, 263–272 (2001).

Linares, C. et al. Immediate and delayed effects of a mass mortality event on gorgonian population dynamics and benthic community structure in the NW Mediterranean Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 305, 127–137 (2005).

Coma, R. et al. Consequences of a mass mortality in populations of Eunicella singularis (Cnidaria: Octocorallia) in Menorca (NW Mediterranean). Marine Ecology Progress Series 327, 51–60 (2006).

Cebrian, E., Uriz, M. J., Garrabou, J. & Ballesteros, E. Sponge mass mortalities in a warming Mediterranean Sea: Are Cyanobacteria-harboring species worse off? PLoS ONE 6, e20211 (2011).

Huete-Stauffer, C. et al. Paramuricea clavata (Anthozoa, Octocorallia) loss in the Marine Protected Area of Tavolara (Sardinia, Italy) due to a mass mortality event. Marine Ecology 32, 107–116 (2011).

Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A. & Savini, D. Biological invasions as a component of global change in stressed marine ecosystems. Marine Pollution Bulletin 46, 542–551 (2003).

Galil, B. S. Taking stock: inventory of alien species in the Mediterranean sea. Biological Invasions 11, 359–372 (2009).

Zenetos, A. et al. Alien species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2010. A contribution to the application of European Union’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Part I. Spatial distribution. Mediterranean Marine Science 10, 381–493 (2010).

Ballesteros, E. Mediterranean coralligenous assemblages: a synthesis of present knowledge. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review 44, 123–195 (2006).

Baldacconi, R. & Corriero, G. Effects of the spread of the alga Caulerpa racemosa var. cylindracea on the sponge assemblage from coralligenous concretions of the Apulian coast (Ionian Sea, Italy). Marine Ecology 30, 337–345 (2009).

Coma, R., Ribes, M., Zabala, M. & Gili, J. M. Growth in a modular colonial marine invertebrate. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 47, 459–470 (1998).

Garrabou, J. & Harmelin, J. G. A 20-year study on life-history traits of a harvested long-lived temperate coral in the NW Mediterranean: insights into conservation and management needs. Journal of Animal Ecology 71, 966–978 (2002).

Teixidó, N., Garrabou, J. & Harmelin, J. G. Low dynamics, high longevity and persistence of sessile structural species dwelling on Mediterranean coralligenous outcrops. PLoS ONE 6, e23744 (2011).

Casas-Güell, E., Teixidó, N., Garrabou, J. & Cebrian, E. Structure and biodiversity of coralligenous assemblages over broad spatial and temporal scales. Marine Biology 162, 901–912 (2015).

Perez, T. et al. Mortalité massive d’invertébrés marins: un événement sans précédent en Méditerranée nord-occidentale. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences - Series III. Sciences de la Vie 323, 853–865 (2000).

Bally, M. & Garrabou, J. Thermodependent bacterial pathogens and mass mortalities in temperate benthic communities: A new case of emerging disease linked to climate change. Global Change Biology 13, 2078–2088 (2007).

Previati, M., Scinto, A., Cerrano, C. & Osinga, R. Oxygen consumption in Mediterranean octocorals under different temperatures. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 390, 39–48 (2010).

Crisci, C. et al. Regional and local environmental conditions do not shape the response to warming of a marine habitat-forming species. Scientific Reports 7, 5069 (2017).

Linares, C. et al. Efectos del cambio climático sobre la gorgonia Paramuricea clavata y el coralígeno asociado en el Parque Nacional Marítimo-Terrestre del archipiélago de Cabrera. In: Proyectos de investigación en Parques Nacionales: convocatoria 2012–2015 (ed. P. Amengual), 45–67 (2017).

Martin, S., Cohu, S., Vignot, C., Zimmerman, G. & Gattuso, J. P. One-year experiment on the physiological response of the Mediterranean crustose coralline alga, Lithophyllum cabiochae, to elevated pCO2 and temperature. Ecology and Evolution 3, 676–693 (2013).

Kruzic, P. & Rodic, P. Impact of climate changes on coralligenous community in the Adriatic Sea. Proceedings of the Second Mediterranean Symposium of coralligenous and other calcareous bioconcretions (Portoroz, Slovenia, 29-30 October 2014) Tunis: RAC-SPA, 100–105 (2014).

Di Camillo, C. G. & Cerrano, C. Mass mortality events in the NW Adriatic Sea: Phase shift from slow- to fast-growing organisms. PLoS ONE 10, e0126689 (2015).

Hereu, B. & Kersting, D. K. Diseases of coralline algae in the Mediterranean Sea. Coral Reefs 35, 713 (2016).

Rodríguez-Prieto, C. Light and temperature requirements for survival, growth and reproduction of the crustose coralline Lithophyllum stictaeforme from the Mediterranean Sea. Botanica Marina 59, 95–104 (2016).

Harmelin, J. G. Pentapora fascialis, a bryozoan under stress: condition on coastal hard bottoms at Port-Cros Island (Port-Cros national Park, France, Mediterranean) and other sites. Scientific Reports of Port-Cros National Park 133, 125–133 (2017).

Ezzat, L., Merle, P. L., Furla, P., Buttler, A. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. The response of the Mediterranean gorgonian Eunicella singularis to thermal stress is independent of its nutritional regime. PLoS ONE 8, e64370 (2013).

Coma, R., Llorente-Llurba, E., Serrano, E., Gili, J. M. & Ribes, M. Natural heterotrophic feeding by a temperate octocoral with symbiotic zooxanthellae: A contribution to understanding the mechanisms of die-off events. Coral Reefs 34, 549–560 (2015).

Movilla, J. et al. Annual response of two Mediterranean azooxanthellate temperate corals to low-pH and high-temperature conditions. Marine Biology 163, 1–14 (2016).

Roghi, F. et al. Decadal evolution of a coralligenous ecosystem under the influence of human impacts and climate change. Biologia Marina Mediterranea 17, 59–62 (2010).

Gatti, G. et al. Seafloor integrity down the harbor waterfront: the coralligenous shoals off Vado Ligure (NW Mediterranean). Advances in Oceanography and Limnology 3, 51–67 (2012).

Piazzi, L., Gennaro, P. & Balata, D. Threats to macroalgal coralligenous assemblages in the Mediterranean Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 64, 2623–2629 (2012).

Ferrigno, F., Appolloni, L., Russo, G. F. & Sandulli, R. Impact of fishing activities on different coralligenous assemblages of Gulf of Naples (Italy). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 98, 41–50 (2018).

Balata, D., Piazzi, L., Cecchi, E. & Cinelli, F. Variability of Mediterranean coralligenous assemblages subject to local variation in sediment deposition. Marine Environmental Research 60, 403–421 (2005).

Birrell, C. L., McCook, L. J. & Willis, B. L. Effects of algal turfs and sediment on coral settlement. Marine Pollution Bulletin 51, 408–414 (2005).

Vermeij, M. J. A. & Sandin, S. A. Density-dependent settlement and mortality structure in the earliest life phases of a coral population. Ecology 89, 1994–2004 (2008).

Arnold, S. N., Steneck, R. S. & Mumby, P. J. Running the gauntlet: Inhibitory effects of algal turfs on the processes of coral recruitment. Marine Ecology Progress Series 414, 91–105 (2010).

de Caralt, S. & Cebrian, E. Impact of an invasive alga (Womersleyella setacea) on sponge assemblages: Compromising the viability of future populations. Biological Invasions 15, 1591–1600 (2013).

Bulleri, F. & Benedetti-Cecchi, L. Facilitation of the introduced green alga Caulerpa racemosa by resident algal turfs: Experimental evaluation of underlying mechanisms. Marine Ecology Progress Series 364, 77–86 (2008).

Scinto, A. et al. Role of a Paramuricea clavata forest in modifying the coralligenous assemblages. In: First Symposium on the Coralligenous and other calcareous bio-concretions of the Mediterranean Sea. Tunis: RAC-SPA, 137–141 (2009).

Ponti, M. et al. Ecological shifts in Mediterranean coralligenous assemblages related to gorgonian forest loss. PLoS ONE 9(7), e102782 (2014).

Ponti, M. et al. The role of gorgonians on the diversity of vagile benthic fauna in Mediterranean rocky habitats. Marine Biology 163, 1–14 (2016).

Valisano, L., Notari, F., Mori, M. & Cerrano, C. Temporal variability of sedimentation rates and mobile fauna inside and outside a gorgonian garden. Marine Ecology 37, 1303–1314 (2016).

Gatti, G. et al. Observational information on a temperate reef community helps understanding the marine climate and ecosystem shift of the 1980–90s. Marine Pollution Bulletin 114, 528–538 (2017).

Ponti, M., Turicchia, E., Ferro, F., Cerrano, C. & Abbiati, M. The understorey of gorgonian forests in mesophotic temperate reefs. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 28 , 1153–1166 (2018).

Wernberg, T. & Connell, S. D. Physical disturbance and subtidal habitat structure on open rocky coasts: Effects of wave exposure, extent and intensity. Journal of Sea Research 59, 237–248 (2008).

Gorman, D. & Connell, S. D. Recovering subtidal forests in human-dominated landscapes. Journal of Applied Ecology 46, 1258–1265 (2009).

Ceccherelli, G., Piazzi, L. & Balata, D. Spread of introduced Caulerpa species in macroalgal habitats. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 280, 1–11 (2002).

Kersting, D. K. et al. Experimental evidence of the synergistic effects of warming and invasive algae on a temperate reef-builder coral. Scientific Reports 5, 18635 (2015).

IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC (2014).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nature Communications 9, 1324 (2018).

Allen, D. et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest Ecology and Management 259, 660–684 (2010).

Lejeusne, C., Chevaldonné, P., Pergent-Martini, C., Boudouresque, C. F. & Pérez, T. Climate change effects on a miniature ocean: the highly diverse, highly impacted Mediterranean Sea. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25, 250–260 (2010).

Vives, F. Aspectes hidrogràfics i planctònics dels voltants de l’Arxipèlag de Cabrera. In: Història natural de l’Arxipèlag de Cabrera (eds Alcover, J. A., Ballesteros, E. & Fornós, J. J.), 487–502 (1993).

Garcés, E., Basterretxea, G. & Tovar-Sánchez, A. Changes in microbial communities in response to submarine groundwater input. Marine Ecology Progress Series 438, 47–58 (2011).

Ballesteros, E. et al. Estat ecològic de les masses d’aigua a les Illes Balears In: I Jornada cientificotècnica Directiva Marc de l’Aigua, Govern de les Illes Balears. 10 pp (2009).

Vázquez-Luis, M., Morató, M., Campillo, J. A. & Guitart, C. High metal contents in the fan mussel Pinna nobilis in the Balearic Archipelago (western Mediterranean Sea) and a review of concentrations in marine bivalves (Pinnidae). Scientia Marina 80, 111–122 (2016).

Ballesteros, E. & Zabala, M. El bentos: el marc físic. In: Història natural de l’Arxipèlag de Cabrera (eds Alcover J. A., Ballesteros E., Fornós, J. J.) 663–685 (1993).

Ballesteros, E., Zabala, M., Uriz, M.J, Garcia-Rubies, A. & Turon, X. In Història Natural de l’arxipèlag de Cabrera (eds Alcover, J. A. & Ballesteros E., Fornós J. J.), 687–730 (1993).

Cebrian, E. & Ballesteros, E. Temporal and spatial variability in shallow- and deep-water populations of the invasive Caulerpa racemosa var. cylindracea in the Western Mediterranean. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 83, 469–474 (2009).

Cebrian, E. & Ballesteros, E. Invasion of Mediterranean benthic assemblages by red alga Lophocladia lallemandii (Montagne) F. Schmitz: Depth-related temporal variability in biomass and phenology. Aquatic Botany 92, 81–85 (2010).

Kipson, S. et al. Rapid biodiversity assessment and monitoring method for highly diverse benthic communities: A case study of mediterranean coralligenous outcrops. PLoS ONE 6, e27103 (2011).

Cebrian, E., Ballesteros, E. & Canals, M. Shallow rocky bottom benthic assemblages as calcium carbonate producers in the Alboran Sea (southwestern Mediterranean). Oceanologica Acta 23, 311–322 (2000).

Clarke, K. R., Somerfield, P. J. & Chapman, M. G. On resemblance measures for ecological studies, including taxonomic dissimilarities and a zero-adjusted Bray-Curtis coefficient for denuded assemblages. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 330, 55–80 (2006).

Anderson, M. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecology 26, 32–46 (2001).

Anderson, M. PERMANOVA: a FORTRAN Computer Program for Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (2005).

Bolker, B. M. et al. Generalized linear mixed models: A practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 24, 127–135 (2009).

Pinheiro, J. C. & Bates, D. M. Linear mixed-effects models: Basic concepts and examples. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS, 3–56 (2000).

Clarke, K. R. & Gorley, R. N. PRIMER v6: User Manual/Tutorial (Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research). PRIMER-E, Plymouth (2006).

Anderson, M., Gorley, R. & Clarke, R. Permanova + for Primer: guide to software and statisticl methods. Primere-E (2008).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2016).

Oksanen, J. Vegan: ecological diversity. R package version 2.3.4. (2018).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Financial support has been provided by a Spanish Ministry Project ANIMA (CGL2016-76341-R), OAPN project (CORCLIM 759S/2012 and 766S/2012) and European Union’s Horizon 2020 (grant agreement No. 689518) MERCES Project. This output reflects only the authors’ view and the European Union cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. J.V. has been funded by a IFUdG2016 grant. Managers of ACNP are acknowledged for sampling permissions. We also thank to David Díaz, Eneko Aspillaga, Pol Capdevila, Bernat Hereu and Fiona Tomas for their collaboration in fieldwork. J.V., C.L. and E.C. are members of the Marine Conservation Research Group (www.medrecover.org; 2017 SGR 1521) and R.C. is part of the Marine Biogeochemistry and Global Change Research Group (2017SGR1011) from the Generalitat de Catalunya.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.C. and C.L. designed the experiment; all authors collected field data; E.B. and M.J.U. carried out the taxonomic identifications; J.V. analyzed the images; R.C., N.B. and J.V. studied the thermal environment; J.V. carried out the statistical analyses; J.V. and E.C. drafted the manuscript and all the authors did substantial contributions to the manuscript and accepted the final version before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verdura, J., Linares, C., Ballesteros, E. et al. Biodiversity loss in a Mediterranean ecosystem due to an extreme warming event unveils the role of an engineering gorgonian species. Sci Rep 9, 5911 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41929-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41929-0

This article is cited by

-

Modeling the effects of climate change on the habitat suitability of Mediterranean gorgonians

Biodiversity and Conservation (2024)

-

Structural attributes and macrofaunal assemblages associated with rose gorgonian gardens (Leptogorgia sp. nov.) in Central Chile: opening the door for conservation actions

Coral Reefs (2024)

-

Unveiling microbiome changes in Mediterranean octocorals during the 2022 marine heatwaves: quantifying key bacterial symbionts and potential pathogens

Microbiome (2023)

-

Thermal acclimatisation to heatwave conditions is rapid but sex-specific in wild zebra finches

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Roles of depth, current speed, and benthic cover in shaping gorgonian assemblages at the Palm Islands (Great Barrier Reef)

Coral Reefs (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.