Abstract

Several etiological theories, in particular neuronal noise and impaired auditory sampling, predicted neurotransmission deficits in dyslexia. Neurometabolites also affect white matter microstructure, where abnormalities were previously reported in dyslexia. However findings from only few magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies using diverse age groups, different brain regions, data processing and reference scaling are inconsistent. We used MEGA-PRESS single-voxel spectroscopy in two ROIs: left temporo-parietal and occipital cortex in 36 adults and 52 children, where half in each group had dyslexia. Dyslexics, on average, had significantly lower total N-acetylaspartate (tNAA) than controls in the occipital cortex. Adults compared to children were characterized by higher choline and creatine in both areas, higher tNAA in left temporo-parietal and lower glutamate in the visual cortex, reflecting maturational changes in cortical microstructure and metabolism. Although the current findings do not support the proposed etiological theories of dyslexia, they show, for the first time, that tNAA, considered to be a neurochemical correlate of white matter integrity, is deficient in the visual cortex in both children and adults with dyslexia. They also point that several neurotransmitters, including ones previously used as reference, change with age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dyslexia is a brain-based difficulty in acquiring fluent reading skills that affects around 10–15% of the population1. Since this disorder is heterogeneous, many different etiological theories have been proposed to explain its symptoms2. Two were specifically linked to neurotransmission deficits, even though still little is known about neurochemical underpinnings of reading disorder. The first theory suggests that dyslexia might be a consequence of neuronal hyperexcitability, which contributes to learning deficits by heightened noise and instability in information processing3. This theory emphasizes the importance of balanced levels of excitation and inhibition within cortical pyramidal-interneuron networks, which support tuning to sensory input, neural timing, and information processing. Excitation–inhibition balance and the precise timing of neural activity can be disrupted by cortical hyperexcitability. On the level of neurotransmitters, this theory predicts heightened level of glutamatergic (Glu or Glx) signalling in dyslexic individuals3, since glutamate concentrations were found to be positively correlated with cortical excitability4. The loss of neuronal synchronization is hypothesized to lead to deficits in low-level temporal auditory processing, the oscillatory neural processes that sample and encode sensory information and impairments in multisensory integration, all of which are key components of reading development. Other theory of impaired auditory sampling5 suggests that the cause of reading disorder lies in a general deficit in synchronization of neuronal oscillations specifically in auditory cortex (phase-locking) in response to external input. However, studies examining cortical oscillations in dyslexia are inconclusive. Some point to synchronization deficits in the delta and theta range of 2–10 Hz5 which corresponds to syllable stress pattern, other show impairments in the low gamma band 25–35 Hz6, which corresponds to phonemic rate pattern. The two mentioned theories of dyslexia are not necessarily contradictory with each other, since the heightened noise level due to neural hyperexcitability might potentially lead to the imperfect synchronization of specific neuronal oscillations (phase-locking) in auditory cortex resulting in impaired auditory sampling.

On the level of neurotransmitters, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) drives the modulation of gamma band7 and gamma band neurophysiological correlates of GABA concentrations have been observed in the visual8,9; temporal10 and motor11 cortex of healthy adults. The role of neurotransmitters in slow frequency theta oscillations is much less understood, but glutamate and choline (Cho) were implicated as the dominant neurotransmitters. Specifically during auditory signal processing in humans an association between glutamate concentration in hippocampus and theta oscillations in frontal areas was reported12. In rodents, hippocampal acetylcholine and theta oscillations seem to be tightly coupled as acetylcholine release accompanies the appearance of theta oscillations13 (for review see Pignatelli et al.14). Since the cortical oscillations studies in dyslexia did not provide conclusive evidence in favour of either theory, here we aim to directly test their predictions by examining if the concentrations of the above mentioned neurometabolites (i.e. GABA, choline and glutamate) are altered in individuals with dyslexia.

At the same time, studding alterations in neurometabolite levels may inform about underlying cytoarchitectonic differences between typical and dyslexic readers. It has been shown that total N-acetylaspartate (tNAA) concentration reflects neuronal density, function or viability15, but also maintains and supports myelination16. Choline is considered a marker of cell membranes in the voxel, which could reflect glial cell density17, the amount of myelin18 or the amount of membrane turnover from breakdown or synthesis19. Therefore increased choline was previously interpreted as reflecting either abnormal myelination or excessive cortical connectivity and thus longer communication route and transmission time20. In the studies where myelination was indirectly measured via fractional anisotropy (FA), significant differences were found between dyslexics and controls - both adults and children, especially in the arcuate fasciculus and corpus callosum21. Thus, various neurotransmitters can affect the neural structure and function at the macroscopic level with specific contributions to white matter microstructure. At the same time dysfunction in cortical connectivity has been hypothesized in individuals with dyslexia by multiple theories of dyslexia, not limiting to the hyperexcitability and impaired auditory sampling models. Overall, the findings of the neurometabolites in dyslexia can provide valuable insights to a broader understanding of neurobiological mechanisms underlying dyslexia.

Until now, only few studies investigated concentrations of neurometabolites in dyslexia. Initial work was carried out by Rae22, who found lower choline/N-acetylaspartate (NAA) ratio in the left temporo-parietal lobe and right cerebellum in 14 dyslexic compared to 15 typically reading males. Additionally, the researchers noticed significant lateralization differences in NAA in the dyslexic group, with lower concentration of NAA in the left compared to right hemisphere. Laycock et al.20 studied neurometabolites in the cerebellum and contradictory to Rae et al.22 found increased Cho/creatine and Cho/NAA in 6 dyslexic adults compared to 6 controls. Subsequently, on a bigger sample of 31 adults Bruno et al.23 revealed that in the left angular gyrus Cho/creatine ratio is negatively correlated with phonological awareness (PA), a skill closely related to reading24. Later, in a group of 75 children (6–10 years old), Pugh and colleagues25 showed a negative correlation of Cho/creatine in the occipital cortex with reading performance, but not with PA. They additionally showed negative correlations between Glu/creatine ratio and reading skill, as well as PA in the same occipital region. In this sample only 10 children met the criteria for reading disorder and when compared to 47 typical readers they showed elevated levels of both Cho and Glu. Pugh et al.25 was also the first to measure GABA concentration with PRESS edited sequence, however no significant effects in GABA concentration were observed. Recently, this group has published a follow up study26 where they reanalyzed spectroscopy from a subsample of 70 children from 201425. Additionally to previous work they reported correlations with response time in cross-modal word matching task where lower GABA/Cr and higher NAA/Cr concentration predicted faster reaction times. What is more, authors showed that the task response time mediates between metabolite concentration (Glu, Cho) and reading ability. Although, main result concerns GABA and NAA differences in cross-modal matching, the mediation in Glu and Cho is highlighted as supportive argument for neural noise hypothesis. Finally, Lebel et al.27 measured neurometabolites’ concentration in the anterior cingulate gyrus (n = 56) and left angular gyrus (n = 45) in a group of preschool children. They reported positive correlations between PA and neurotransmitters - Glu, creatine and inositol in anterior cingulate. Positive correlation of PA and Glu reported by Lebel et al.27 is in the opposite direction to the findings of Pugh et al.25. Similarly Rae et al.22 found decreased, while others20,25 increased concentration of choline in dyslexic compared to control samples.

Among the potential reasons causing the inconsistencies in previous studies might be the differences in the age of participants (pre-reading children vs. school-age children vs. adults), differences in the reference scaling (absolute concentration vs. reference to creatine or NAA) as well as brain regions examined (left temporo-parietal vs. occipital vs. anterior cingulate cortex vs. cerebellum). Additionally, even though in each previous study several different neurometabolites were examined, the authors used a nominal significance of p < 0.05 to report positive findings of group differences20,22,25, which might have led to false positives. Neurometabolites concentration is likely to differ between age ranges, reflecting changes in glutamatergic neurotransmission and refinement of cortical networks in particular through axonal elongation, myelination and pruning28,29,30. It has been shown that during initial education (5–12 years) NAA rises by 7% and Cr by 10% in occipital and parietal voxels respectively29. The same authors did not obtain significant results in mid education group (12–18 years). In a wider age group (4–13 and 18–33 year olds analyzed together) negative slope of Glu/Cr ratio was determined31 with authors’ assumption that Cr concentration remains stationary. In fact, when absolute concentrations of Glu and Cr were analyzed30, both were characterized with negative age slope in participants aged from 18 to 31. Bearing in mind these maturational changes (in particular glutamate decreases31 and NAA rises29 from childhood to young adulthood in occipital cortices), it is difficult to form definite conclusions about the alternations of brain neurochemistry in dyslexia. Furthermore, so far only three studies directly compared dyslexic to typically reading subjects20,22,25, but all had relatively small samples of dyslexic subjects.

Here we aimed at systematic analysis of potential neurometabolite abnormalities in dyslexia by examining the concentration of glutamate (Glu and Glx), choline, NAA and GABA in both adult and children samples. Additionally, we tested whether Cr level can be utilized as a reference. We hypothesize that, if reading disorder is associated with poor phase synchronization in low frequency bands, as suggested by Goswami5, dyslexic groups should show abnormalities in the concentration of glutamate and/or choline. If, however, as suggested by Lehongre et al.6, dyslexia is related to poor synchronization in the gamma band, concentration of GABA should be altered. Heightened glutamate in dyslexics compared to control subjects is also expected by the neuronal noise theory3. Finally, changes in NAA and choline can inform about white matter microstructure differences previously implicated in dyslexia21. Since still little is known about whether dyslexia effects change with age, besides the effect of group (dyslexic vs. typical readers), we examined both age effects and interactions on neurometabolites’ concentration. Thus the present study, as compared to previous ones examining similar age ranges23,25,27, has an additional insight of examining the commonalities and differences between school-aged children and experienced adult readers in the level of neurotransmiters in two brain regions present in the previous studies (i.e. occipital cortex, and left temporo-parietal cortex including the angular gyrus). By examining two different brain regions in the same subjects we can infer about the specificity of neurotransmiter differences in dyslexia. Finally, in the supplementary analyses we compare different reference scaling methods and suggest directions for future research. In order for the reader to compare current findings with the previous literature we report all effects surviving the nominal significance of p < 0.05, but focus more on results surviving more stringent statistical threshold corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Behavioral measures

In adults Adult Reading History Questionnaire(ARHQ) score (40.6 ± 17.9) was highly correlated with word reading (r = −0.57, p < 0.001) and pseudoword reading (r = −0.73, p < 0.001). In both reading tests adults with dyslexia performed significantly lower than adult control group (p < 0.001, see Table 1). Dyslexic adults were also significantly slower than controls at naming letters and numbers in Rapid automatized naming (RAN), but had similar performance in the objects and colors subtests. This pattern of results remained unchanged when several subjects were removed from the analysis due to spectral artifacts. It is important to mention that both ARHQ and pseudowords reading test were used to classify subjects to the groups in adult sample.

Dyslexic children had significantly worse performance than children from the control group in all behavioral tests - word and pseudoword reading, both subscales of RAN (objects & colors and letters & digits), and phonological task based on pseudowords. This pattern of results was not affected by removing subjects with spectral artifacts. Descriptive statistics and results of the statistical comparisons between the dyslexic and control groups are presented in the Table 1.

Spectroscopy - data quantity and quality

In adult group 4 spectra from visual cortex and 3 from left temporo-parietal cortex were rejected from the analysis due to strong artifacts. Two additional GABA estimates from visual cortex were rejected after GANNET preprocessing. In the end, 33 spectra from the left temporo-parietal lobe (17 dyslexic and 16 control adults) and 32 spectra from the visual cortex (16 dyslexic and 16 control adults) were being taken under consideration (30 GABA estimates from visual cortex − 15 dyslexic and 15 control adults).

In children sample, after data reconstruction 1 subject was rejected due to heavy, presumably motion artifacts in both spectra. Eight more spectra from left temporo-parietal cortex and 1 from visual cortex were declassified upon detailed visual inspection of LCModel printout. Additionally, 4 GABA estimates were rejected after preprocessing in GANNET (3 from left temporo-parietal cortex and 1 from visual cortex). Invalid spectra were misaligned during spectral registration and subsequently characterized with an abnormal shape of peaks and baseline. As a result, 43 spectra from left temporo-parietal lobe (20 dyslexic and 23 control children) and 50 spectra from visual cortex (25 dyslexic and 25 control children) were further analyzed (40 − 17 dyslexic and 23 control children and 49 − 25 dyslexic and 25 control children GABA estimates, respectively).

Spectroscopy - group analyses

Choline (Cho)

Two way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of age in both left temporo-parietal cortex and visual cortex (F(1,72) = 30.68, p < 0.001***, BF10 > 1000 and F(1,78) = 30.19, p < 0.001***, BF10 > 1000 respectively). Adults on average had higher choline concentration than children by 14.1% in temporo-parietal and 10.1% in visual cortex voxels. Interactions between age and group reached nominal significance, but did not withstood correction for multiple comparisons with F(1,72) = 5.15, p = 0.026, BF10 = 2.459 (left temporo-parietal cortex) and F(1,78) = 6.52, p = 0.013, BF10 = 4.007 (visual cortex). Dyslexic children compared to control children had lower by 7.6% absolute choline concentration in the left temporo-parietal (p = 0.05, BF10 = 1.438) and by 5.5% in visual cortex (p = 0.031, BF10 = 1.466) (uncorrected for multiple comparisons). In adults the difference between the experimental groups did not reach nominal significance in neither regions, although dyslexic adults tended to have higher choline concentration than controls. Therefore there was no main effect of dyslexia.

Glutamate and glutamine (Glu & Glx)

In the visual, but not in the left temporo-parietal cortex, a main effect of age was found for both Glu and Glx (F(1,78) = 52.03, p < 0.001***, BF10 > 1000 and F(1,78) = 33.53, p < 0.001***, BF10 > 1000 respectively), with children having higher concentration of neurotransmitters than adults (17.9% - Glu and 13.6% - Glx). There was no significant effect of group nor interaction between age and group in neither Glu nor Glx.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)

In both brain areas, neither main effects of age and group nor interaction between age and group reached significance for GABA.

Creatine (Cr)

In both brain areas there was a significant effect of age (F(1,72) = 42.79, p < 0.001***, BF10 > 1000 for the left temporo-parietal and F(1,78) = 12.22, p = 0.001**, BF10 = 37.307 for visual cortex). Children had lower concentration of Cr than adults by 17.8% in temporo-parietal and by 5.7% in the visual cortex.

Total N-acetyl-aspartate (tNAA)

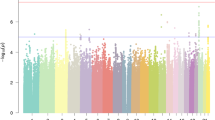

In the visual cortex, but not in the left temporo-parietal cortex, there was a significant main effect of dyslexia for the tNAA concentration (F(1,78) = 7.52, p = 0.008**, BF10 = 9.811, see Fig. 1). The effect remained significant (F(1,76) = 7.23, p = 0.009**, BF10 = 4.598) after removal of two control children with outlying tNAA concentration (>3 SD above mean). Subjects with dyslexia had on average lower concentration of tNAA by 4.5% than typically reading controls. There was also a significant effect of age in the left temporo-parietal cortex (F(1,72) = 23.73, p < 0.001***, BF10 > 1000), where children had lower concentration of tNAA than adults by 10.8%.

The concentration of choline (Cho), N-acetyl-aspartate (tNAA), glutamate (Glu & Glx) in control and dyslexic adults and children in the left temporo-parietal and occipital cortex. Significant effect of age is present in the left temporo-parietal cortex for Cho and tNAA, and in the visual cortex for Cho and glutamate (Glu & Glx). Significant effect of group is observed for the tNAA concentration in the visual cortex. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01.

Brain - behavior correlations

We performed correlations within the group of adults and children, combining both control and dyslexic individuals. This analysis showed that choline concentration correlated with RAN objects and colors differently in adults and children. The correlation was positive in adult sample (r = 0.516, p = 0.002** in the left temporo-parietal cortex and r = 0.449, p = 0.01 in the visual cortex), meaning the higher the concentration of this metabolite the slower naming speed (see Fig. 2). In children the correlation between RAN and choline was of a different direction, i.e. the higher the concentration of choline the faster naming speed, but it did not approach significance (r = −0.299, p = 0.052 in the left temporo-parietal cortex and r = −0.109, p = 0.45 in the visual cortex). Importantly, the difference in correlations coefficients between adults and children was significant (z = 3.64, p < 0.001 for the temporo-parietal and z = 2.51, p = 0.012 for visual cortex). Several weaker correlations were found, but they did not survive the correction for multiple comparisons. Specifically, in children there was a positive correlation between choline concentration in the visual cortex and words reading (r = 0.284, p = 0.045) and a negative correlation between tNAA in the temporo-parietal cortex and time needed to name objects and colors (r = −0.372, p = 0.014). Phonological awareness in children was also correlated with metabolite concentration, but no significant effects were found. In adults, glutamate in the left temporo-parietal cortex was positively correlated with RAN objects and colors (r = 0.367, p = 0.036 - Glu; r = 0.385, p = 0.027 - Glx).

Discussion

The current study is the first to examine brain neurochemistry in typically developing and dyslexic children and adults in the two brain regions: occipital cortex, and left temporo-parietal cortex including the angular gyrus. We tested the predictions of different etiological theories of dyslexia related to neurotransmission deficits and aimed to disentangle inconsistencies between previous findings by exploring how participants’ age or different preprocessing steps (see supplementary materials) affect the results.

We found that dyslexic individuals, irrespective of age, had significantly lower tNAA than controls in the occipital cortex. This was the only group effect related to dyslexia, which survived the correction for multiple comparisons. NAA is the most prominent neurotransmitter detected in the normal human brain, which reflects neuronal density, function or viability15, but is also considered to be a neurochemical correlate of neuron-oligodendrocyte (axon-myelin) integrity32. Reduced tNAA in dyslexic subjects suggests white matter microstructure abnormalities since the concentration of tNAA is positively correlated with fractional anisotropy (FA)33,34. FA measures the amount of coherence of water diffusion which putatively reflects the amount of myelination in axonal bundles or the coherence of fiber tracts. Diffusion weighted studies identified lower FA mainly in the left temporo-parietal areas in dyslexia in both children and adults21, whereas occipital areas seem to be less frequently found35,36. However, occipital cortex was for a long time a focus of neurofunctional studies on dyslexia, showing the abnormalities in processing of visual motion37 and other stimuli such as symbol strings38. NAA differences in reading skill were identified only in one recent MRS study, where higher NAA/Cr concentration in the occipital cortex predicted faster reaction times in a cross-modal matching task with language stimuli (letters, words and pseudowords) in children26. This result would be in line with ours, where controls had higher concentration of tNAA in the occipital cortex than dyslexics. Del Tufo and colleagues suggested that higher NAA in the occipital cortex corresponds to more intact white matter reading network and specifically to left arcuate fasciculus in the temporo-parietal cortex, which connectivity was related to individual differences in cross-modal brain activity in developing readers. However, we found no effects of dyslexia in the concentration of tNAA in the left temporo-parietal cortex. Moreover, lower tNAA in the occipital cortex characteristic for dyslexic subjects in the current study was also not predicted by the two etiological theories of dyslexia.

Neuronal noise hypothesis predicted heightened level of glutamate3 in dyslexia. However no such effect was present in the current study. So far only one study reported elevated levels of Glu/creatine in dyslexic children in the occipital cortex25. Even though the stated effect size for this group difference was large (Cohen’s d = 0.79), given the low sample of dyslexic children (n = 10) and no correction for multiple comparisons it is not unlikely that this estimate might be inflated39. Previous correlational MRS studies showed mixed results for glutamate, with positive correlation with phonological awareness in anterior cingulate in pre-reading children27 and negative correlation for Glu/creatine with both reading performance and phonological awareness in the occipital cortex in school-age children25. In our study, glutamate concentration was not related to reading, phonological awareness or naming speed in children, whereas in adults higher glutamate concentration was related to slower naming speed, but this result did not survive correction for multiple comparisons.

Altered levels of glutamate together with choline would be also expected by impaired auditory sampling theory for theta oscillations, which correspond to speech syllables12,14. With respect to choline, our results suggest that its role in reading and dyslexia can change with age. Specifically, in adults, but not in children, higher choline in both occipital and temporo-parietal cortex was related with slower naming speed in the RAN test. This result is in line with Bruno et al. (2013), who found a negative correlation between choline in left angular gyrus and phonological skills in young adults23. RAN is considered to be a phonological skill reflecting the speed of access to phonological information in the long-term memory40. Similarly to PA, RAN is a reliable predictor of reading skills, especially in transparent orthographies such as Polish. In contrast to Pugh et al. (2014), where a negative correlation between Cho/creatine and reading skills was found in occipital cortex in children, we did not observe any significant correlations between choline and reading or reading related skills in children. Here, we found that the concentration of creatine might change with age, as adults had higher absolute concentration of creatine than children. Given this, pairwise correlations between Cho/creatine and reading skills not adjusted for age might be difficult to interpret25. Additionally, we found anecdotal evidence for an interaction between age and group in choline concentration both in temporo-parietal and occipital cortex with dyslexic children compared to control children having lower choline concentration (nominally significant), whereas dyslexic adults having higher choline concentration than typically reading adults. Importantly, such interaction was observed irrespective of scaling or correction for tissue composition (see Supplementary Materials). Future studies should test if this result holds in larger samples. Our results are not consistent with Rae’s et al.22 study, where Cho/NAA ratio was reported to be lower in temporo-parietal regions in adult dyslexic men compared to controls (but see Laycock et al. 2008 for findings in the opposite direction in the cerebellum). The discrepancy might be related to reference scaling to NAA, when they used scaling to creatine differences between groups became non-significant22. In fact, in the current study the absolute concentration of tNAA differed between dyslexic and control subjects in the visual cortex and between children and adults in the temporo-parietal cortex, yielding scaling to tNAA illegitimate. Our results stand also in contrast to previous findings of elevated levels of Cho/creatine in dyslexic children in the occipital cortex25. Since the results of both their and our study survived only nominal significance, future research in larger samples is needed to resolve these discrepant findings.

Meanwhile, no significant differences in GABA concentration, which drive oscillations in high frequency bands, were found in neither of the groups. GABA is still difficult to measure compared to glutamate or choline concentration and even with an improved data processing pipeline we did not come to conclusive results. The calculated Bayesian factor (alternative/null) suggested that the data were 0.296:1 for visual and 0.427:1 for temporo-parietal in favor of the null hypothesis (no differences between controls and dyslexic), or rather, 3.38 or 2.34 times more likely to occur under a model without including an effect of dyslexia, rather than a model with it. Alternatively, it would take more than 272 subjects to prove 2% difference in GABA concentration in the left temporo-parietal cortex based on power analysis. Thus GABA (if relevant) needs to be further examined in a much larger sample with a more robust protocol.

Apart from the effect of dyslexia on the concentration of neurometabolites, we observed several maturational changes. In particular adults compared to children were characterized by lower glutamate, especially in the visual cortex, in line with previous studies30,31. Age-related reduction in density of glutamatergic NMDA receptors41 and glutamate-glutamine cycle flux42 could lead to reduced glutamate driven activation and cognitive deficits. However, since glutamate reduction was related to age but not dyslexia in our sample, the decrease in metabolites is rather the result of maturation of neuronal system and its metabolism. Such an effect, reviewed by Segovia in 2001, is linked to elevated metabolic activity in children and changes in glutamatergic neurotransmission28. What is new in the field, higher choline levels in adults than in children were found in both visual and temporo-parietal cortex. As stated in introduction, choline is considered a marker of cell membranes in the voxel i.e. the amount of membrane turnover from breakdown or synthesis. It has been shown that choline pool measured in 1H-MRS and i.e. glycerophosphorylethanolamine and glycerophosphorylcholine measured by 31P-MRS increases with age18. Our results are consistent with age-related dynamics of tissue growth measured by MR relaxometry and diffusion43. The relation between visible choline and maturation was not well studied in humans but other authors reported increases in Cho related to aging in rats44. According to the their hypothesis the uptake of acetylocholine might be impaired by aging, leading to higher signal of free choline measured by MRS. The result presented here is especially interesting in the context of previously reported discrepancies in choline findings20,22,23,25 depending presumably on age of participants (anecdotal interaction was detected here). We also found that children had lower concentration than adults of tNAA in the left temporo-parietal cortex and creatine in both brain areas in line with increase measured in 5–12 y/o children29. To sum up, we observed increase in tNAA, Cr, Cho considered as markers of changes in cortical microstructure and Glu, a measure of increased metabolism. Thus, these results question the use of tNAA or Cr (generally thought to be stable45) as a reference when comparing different age groups i.e. in dyslexia studies. It seems that the normalization of metabolites to creatine or tNAA, limits possible interpretations and future studies measuring absolute metabolite concentrations relative to water signal would be more valuable.

A potential limitation of our study is that we used slightly different acquisition parameters in the group of children - shorter acquisition to reduce number of spectra affected by motion and smaller voxel in temporo-parietal lobe to better correspond with anatomical features. However, the applied corrections for partial volume effect and locally measured water signal make the spectra comparable between the groups with a use of applied statistical tests (assuming unequal variance where relevant). Nevertheless, measuring metabolites of low signal such as GABA is still a challenge in a reasonable amount of acquisition time. We look forward to novel methods of online motion correction for longer spectroscopic acquisition.

To conclude, although the current findings do not lend support to neither of the proposed etiological theories of dyslexia, they show, for the first time, that tNAA, considered to be a neurochemical correlate of white matter integrity, is deficient in the visual cortex in both children and adults with dyslexia. They also point that several neurotransmitters, including ones previously used as reference, change with age. However, current results should be interpreted with caution given our cross-sectional data. Future studies should employ a longitudinal approach to examine developmental changes in neurometabolites ideally from the pre-reading period.

Methods

The general inclusion criteria for both adult and children samples were: good overall health, right-handedness, normal (or corrected to normal) vision, normal hearing, no history of neurological illness or brain damage and no symptoms of ADHD. All participants speak Polish as their first language. The study was approved by the Warsaw University Ethical Committee and carried out in accordance to the provisions of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All adult participants and parents gave written informed consent to the study, and the children agreed orally.

Participants - adults

36 adult volunteers (12 females/24 males, mean age 27.3 ± 3.8 y/o, 21.1–39.8 y/o) were included in the study. All participants completed higher education.To select subjects for dyslexic and control group, we used three different criteria and the subject had to meet at least two of them to be included in the dyslexic group. First criterion was the formal dyslexia diagnosis. However, even though 14 subjects obtained dyslexia diagnosis in childhood, dyslexia was not as commonly known and diagnosed in Poland in the 1980s. We thus decided to introduce additional criteria. The second one based on the ARHQ score, commonly used to screen for the reading problem in families in the dyslexia research. A criterion was met if the ARHQ score was higher than 4046. Third criterion was the pseudoword reading score. The criterion was met if the subjects obtained a score lower than group median (Med = 69, Mean = 76). 4 subjects that were not previously diagnosed with dyslexia met both criteria: for ARHQ and pseudoword reading. These subjects were also classified as dyslexics. All 14 individuals with dyslexia diagnosis in childhood also scored above 40 point cut off in the ARHQ. Then from the larger group of volunteers we selected subjects without problems with reading (subjects that met at most one of the criteria described above) matching for age and sex to the dyslexic group (see Table 1). In result, we selected 18 dyslexics and 18 controls for the analysis reported in the paper.

Participants - children

52 children (22 females/30 males, mean age 11.06 ± 0.97 y/o, range 9–12.9 y/o) from third to fifth grade of elementary school were recruited from the larger sample taking part in a different study at the Nencki Institute. The dyslexia diagnosis47 and the IQ assessment (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children48) was conducted within this larger study. We selected 26 children with dyslexia diagnosis, and matched (by age and gender) 26 typically reading controls. All children had average or above-average IQ. The two groups did not differ in age or sex (see Table 1). Additionally, we made sure that the children were born at term (≥37 weeks).

Behavioral measures

Apart from neuroimaging all subjects were tested on words and pseudowords reading speed49 as well as rapid automatized naming - RAN50 with two subtests: objects & colors and letters & digits. The amount of words and pseudowords read per minute was compared between the groups. For the RAN test, the summed time for naming objects and colors as well as letters and digits subtests was compared. All children were tested with a battery of phonological awareness tasks based on pseudowords in which both syllable and phoneme manipulation level was included47. Results of behavioral measures are presented in the Table 1.

MR Spectroscopy and Imaging

MRI was performed on Siemens Magnetom TRIO 3 T using 32CH receiving coil. MEGA-PRESS spectroscopy51 (Siemens research agreement WIP-529) was acquired from two locations – occipital (visual) cortex and left temporo-parietal cortex. Voxels were carefully placed based on 3D T1-weighted images (TR = 3000 ms, TI = 900 ms, 1 × 1 × 1 mm resolution) reconstructed in 3 planes (see Fig. 3).

Spectroscopy acquisition was done with TR = 2000 ms and TE = 68 ms. Acquisition protocol was validated in the group of adults with 192 averages for both edited and non-edited spectra (NA = 192*2). A special attention was paid to quality of MEGA-PRESS edited spectrum thus longer acquisition time was used to better estimate differential spectrum of GABA. However, spectra averaged across >10 min were frequently corrupted due to bad initial calibration, field drift or subjects’ motion. Further, we decided to shorten the acquisition in the whole group of children to NA = 96*2 (from 12 m 50 s to 6 m 25 s) and repeat whole measurement in case of strong artifacts (with the subject’s consent). We think that such modification was legitimate, since all metabolites of interest apart from GABA still withstood conservative threshold of CRLB < 15%52 (Cramér–Rao lower bound - an error of signal modeling used for estimating maximum variance in metabolites concentration). The acquisition parameters were comparable to recent studies where standard PRESS sequence was used23,27. In adults the voxel size was 30 × 30 × 15 mm in both the visual cortex and left temporo-parietal cortex. In children the voxel was of the same size in visual cortex while the size was slightly reduced in temporo-parietal lobe (from 30 × 30 × 15 to 25 × 25 × 15 mm) to better correspond with angular gyrus anatomical features.

Water unsuppressed scan (NA = 16) was acquired to reference the metabolites concentrations. T1-weighted volumes were segmented in SPM8 (New Segment) and coregistered with individual voxel masks in order to correct for partial volume effects. Spectral analysis was performed in Gannet53 - GABA and LCModel53 - alanine, aspartate, creatine, GABA, Glu, Gln, GSH, choline compounds (Cho), lactate, myo-inositol, NAA, NAAG, scyllo-inositol, and taurine. Spectra were assessed by a spectroscopist with a regard to SNR, shape of baseline, residual noise, symmetry and width of singlets (NAA, Cr) and voxel position. GABA estimation was performed in Gannet with the raw data (Siemens TWIX) with the following steps: (1) coil channel combine and phase correction, (2) frequency drift correction, (3) calculation of differential spectrum, (4) fitting with the gaussian peak. (5) Then, the results of GABA were corrected for partial volume effects in respect to CSF, GM/WM ratio as well as tissue specific relaxation times54. Some spectra were misaligned during GANNET preprocessing and also disqualified from analysis.

LCModel was used to calculate absolute metabolite concentration based on MEGA-OFF spectrum (Fig. 4). Siemens RDA (spectra averaged on the scanner) were fitted with the simulated basis set consisting of 14 metabolites55. LCModel’s reference water concentration was corrected based on properties of voxel specific tissue volume fractions56.

Metabolites of interest and confounding factors

According to presented literature we hypothesised that Cho, Glu (and Glx), NAA or GABA concentration would differ in dyslexia. Additionally, we tested whether Cr level can be utilized as a reference.

Type of analysis, multiple comparison correction

We used a 2 × 2 ANOVA model with group (dyslexic vs. control) and age (adult vs. children) as factors. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed if main effects or interaction were found significant. In order to compare current findings with the previous literature20,22,25 we report all effects surviving the nominal significance of p < 0.05, but focus more on results surviving more stringent statistical threshold corrected for multiple comparisons (5 metabolites) resulting in nominal threshold of p < 0.01. The results that survive correction for multiple comparisons are marked with 2 or more asterisks. Bayesian ANOVA was performed for estimating ratio of the likelihood probability of two competing hypotheses - Bayes factor57. Here we assume that for BF10 > 3 there is a substantial evidence for alternative hypothesis comparing to null and symmetrically for BF10 < 1/3 for null comparing to alternative. Bayes factor does not require multiple comparison correction58.

Applied corrections and confounding factors

Different scaling methods may potentially lead to bias results i.e. when considering age and voxel position. We decided to show fully corrected concentrations for relaxation, tissue composition and scaled with water concentration within a voxel as a main result. Additionally, we were obliged to test for any effect of scaling methods used previously by referenced authors such as: scaling to tNAA or Cr and less sophisticated tissue correction. Such information is presented in supplementary materials for the purpose of comparisons with published studies and thus was not taken into account in multiple comparison correction.

Brain behavior correlations

Furthermore, similarly to previous studies23,25 we performed Pearson’s correlation between Cho, Glu, Glx, GABA, tNAA and behavioral tests (words and pseudowords reading and RAN). The correlations were performed separately for adults and children.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Shaywitz, S. E. et al. Functional disruption in the organization of the brain for reading in dyslexia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 2636–2641 (1998).

Ramus, F. & Ahissar, M. Developmental dyslexia: the difficulties of interpreting poor performance, and the importance of normal performance. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 29, 104–122 (2012).

Hancock, R., Pugh, K. R. & Hoeft, F. Neural Noise Hypothesis of Developmental Dyslexia: (Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21, 434-448, 2017). Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 909 (2017).

Stagg, C. J. et al. Relationship between physiological measures of excitability and levels of glutamate and GABA in the human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 589, 5845–5855 (2011).

Goswami, U. A temporal sampling framework for developmental dyslexia. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 3–10 (2011).

Lehongre, K., Ramus, F., Villiermet, N., Schwartz, D. & Giraud, A.-L. Altered Low-Gamma Sampling in Auditory Cortex Accounts for the Three Main Facets of Dyslexia. Neuron 72, 1080–1090 (2011).

Buzsáki, G. & Wang, X.-J. Mechanisms of Gamma Oscillations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35, 203–225 (2012).

Edden, R. A. E., Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., Freeman, T. C. A. & Singh, K. D. Orientation discrimination performance is predicted by GABA concentration and gamma oscillation frequency in human primary visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 29, 15721–15726 (2009).

Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., Edden, R. A. E., Jones, D. K., Swettenham, J. B. & Singh, K. D. Resting GABA concentration predicts peak gamma frequency and fMRI amplitude in response to visual stimulation in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8356–8361 (2009).

Balz, J. et al. GABA concentration in superior temporal sulcus predicts gamma power and perception in the sound-induced flash illusion. Neuroimage 125, 724–730 (2016).

Gaetz, W. et al. GABA estimation in the brains of children on the autism spectrum: measurement precision and regional cortical variation. Neuroimage 86, 1–9 (2014).

Gallinat, J. et al. Hippocampal glutamate concentration predicts cerebral theta oscillations during cognitive processing. Psychopharmacology 187, 103–111 (2006).

Zhang, H., Lin, S.-C. & Nicolelis, M. A. L. Spatiotemporal coupling between hippocampal acetylcholine release and theta oscillations in vivo. J. Neurosci. 30, 13431–13440 (2010).

Pignatelli, M., Beyeler, A. & Leinekugel, X. Neural circuits underlying the generation of theta oscillations. J. Physiol. Paris 106, 81–92 (2012).

Rae, C. D. A guide to the metabolic pathways and function of metabolites observed in human brain 1H magnetic resonance spectra. Neurochem. Res. 39, 1–36 (2014).

Singhal, N. K. et al. The neuronal metabolite NAA regulates histone H3 methylation in oligodendrocytes and myelin lipid composition. Exp. Brain Res. 235, 279–292 (2017).

Gupta, R. K. et al. Relationships between choline magnetic resonance spectroscopy, apparent diffusion coefficient and quantitative histopathology in human glioma. J. Neurooncol. 50, 215–226 (2000).

Blüml, S., Seymour, K. J. & Ross, B. D. Developmental changes in choline- and ethanolamine-containing compounds measured with proton-decoupled (31)P MRS in in vivo human brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 42, 643–654 (1999).

Hattingen, E. et al. Combined (1)H and (31)P spectroscopy provides new insights into the pathobiochemistry of brain damage in multiple sclerosis. NMR Biomed. 24, 536–546 (2011).

Laycock, S. K. et al. Cerebellar volume and cerebellar metabolic characteristics in adults with dyslexia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1416.002 (2008).

Vandermosten, M., Boets, B., Wouters, J. & Ghesquière, P. A qualitative and quantitative review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in reading and dyslexia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1532–1552 (2012).

Rae, C. et al. Metabolic abnormalities in developmental dyslexia detected by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Lancet 351, 1849–1852 (1998).

Bruno, J. L., Lu, Z.-L. & Manis, F. R. Phonological processing is uniquely associated with neuro-metabolic concentration. Neuroimage 67, 175–181 (2013).

Pennington, B. F., van Orden, G. C., Smith, S. D., Green, P. A. & Haith, M. M. Phonological Processing Skills and Deficits in Adult Dyslexics. Child Dev. 61, 1753 (1990).

Pugh, K. R. et al. Glutamate and choline levels predict individual differences in reading ability in emergent readers. J. Neurosci. 34, 4082–4089 (2014).

Del Tufo, S. N. et al. Neurochemistry Predicts Convergence of Written and Spoken Language: A Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study of Cross-Modal Language Integration. Front. Psychol. 9, 1507 (2018).

Lebel, C., MacMaster, F. P. & Dewey, D. Brain metabolite levels and language abilities in preschool children. Brain Behav. 6, e00547 (2016).

Segovia, G., Porras, A., Del Arco, A. & Mora, F. Glutamatergic neurotransmission in aging: a critical perspective. Mech. Ageing Dev. 122, 1–29 (2001).

Blüml, S. et al. Metabolic maturation of the human brain from birth through adolescence: insights from in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Cereb. Cortex 23, 2944–2955 (2013).

Marsman, A. et al. Glutamate changes in healthy young adulthood. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 23, 1484–1490 (2013).

Shimizu, M. et al. Maturational decrease of glutamate in the human cerebral cortex from childhood to young adulthood: aH-MR spectroscopy study. Pediatr. Res. 82, 749–752 (2017).

Xu, H. et al. Evaluation of neuron-glia integrity by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Implications for psychiatric disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 71, 563–577 (2016).

Sijens, P. E. et al. Analysis of the human brain in primary progressive multiple sclerosis with mapping of the spatial distributions using 1H MR spectroscopy and diffusion tensor imaging. Eur. Radiol. 15, 1686–1693 (2005).

Tang, C. Y. et al. Correlations between Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) and Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (1H MRS) in schizophrenic patients and normal controls. BMC Psychiatry 7, 25 (2007).

Richards, T. L. & Berninger, V. W. Abnormal fMRI Connectivity in Children with Dyslexia During a Phoneme Task: Before But Not After Treatment. J. Neurolinguistics 21, 294–304 (2008).

Steinbrink, C. et al. The contribution of white and gray matter differences to developmental dyslexia: Insights from DTI and VBM at 3.0T. Neuropsychologia 46, 3170–3178 (2008).

Eden, G. F. et al. Abnormal processing of visual motion in dyslexia revealed by functional brain imaging. Nature 382, 66–69 (1996).

Price, G. R. & Ansari, D. Symbol processing in the left angular gyrus: evidence from passive perception of digits. Neuroimage 57, 1205–1211 (2011).

Ramus, F., Altarelli, I., Jednoróg, K., Zhao, J. & Scotto di Covella, L. Neuroanatomy of developmental dyslexia: Pitfalls and promise. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 84, 434–452 (2018).

Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., Laughon, P. & Simmons, K. Development of young readers’ phonological processing abilities. J. Educ. Psychol. 85, 83–103 (1993).

Peterson, C. & Cotman, C. W. Strain-dependent decrease in glutamate binding to the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor during aging. Neurosci. Lett. 104, 309–313 (1989).

Boumezbeur, F. et al. Altered brain mitochondrial metabolism in healthy aging as assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30, 211–221 (2010).

Yeatman, J. D., Wandell, B. A. & Mezer, A. A. Lifespan maturation and degeneration of human brain white matter. Nat. Commun. 5, 4932 (2014).

Katz-Brull, R., Koudinov, A. R. & Degani, H. Choline in the aging brain. Brain Res. 951, 158–165 (2002).

Yiannoutsos, C. T., Nakas, C. T., Navia, B. A. & proton MRS Consortium. Assessing multiple-group diagnostic problems with multi-dimensional receiver operating characteristic surfaces: application to proton MR Spectroscopy (MRS) in HIV-related neurological injury. Neuroimage 40, 248–255 (2008).

Black, J. M. et al. Maternal history of reading difficulty is associated with reduced language-related gray matter in beginning readers. Neuroimage 59, 3021–3032 (2012).

Bogdanowicz, M. et al. Diagnoza dysleksji u uczniów klasy III szkoły podstawowej: przewodnik diagnostyczny (2008).

Matczak, A., (tłumacz), A. P., Ciarkowska, W. & Wechsler, D. Skala inteligencji D. Wechslera dla dzieci - wersja zmodyfikowana (WISC - R): podręcznik (2008).

Szczerbiński, M. & Pelc-Pękala, O. Zestaw metod diagnozy trudności w czytaniu: Test Dekodowania (2013).

Fecenec, D. Test szybkiego nazywania: zeszyt testowy - wersja S. (Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych (2008).

Mullins, P. G. et al. Current practice in the use of MEGA-PRESS spectroscopy for the detection of GABA. Neuroimage 86, 43–52 (2014).

Kreis, R. The trouble with quality filtering based on relative Cramér-Rao lower bounds. Magn. Reson. Med. 75, 15–18 (2016).

Edden, R. A. E., Puts, N. A. J., Harris, A. D., Barker, P. B. & Evans, C. J. Gannet: A batch-processing tool for the quantitative analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid–edited MR spectroscopy spectra. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 40, 1445–1452 (2014).

Harris, A. D., Puts, N. A. J. & Edden, R. A. E. Tissue correction for GABA-edited MRS: Considerations of voxel composition, tissue segmentation, and tissue relaxations. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 42, 1431–1440 (2015).

Dydak, U. et al. In vivo measurement of brain GABA concentrations by magnetic resonance spectroscopy in smelters occupationally exposed to manganese. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 219–224 (2011).

Gasparovic, C. et al. Use of tissue water as a concentration reference for proton spectroscopic imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 55, 1219–1226 (2006).

Kass, R. E. & Raftery, A. E. Bayes Factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90, 773 (1995).

Gelman, A., Hill, J. & Yajima, M. Why We (Usually) Don’t Have to Worry About Multiple Comparisons. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 5, 189–211 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the National Science Centre (2015/17/N/HS6/03013 and 2014/14/A/HS6/00294). This project was realized with the aid of CePT research infrastructure purchased with funds from the European Regional Development Fund as part of the Innovative Economy Operational Programme, 2007–2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K. and K.J. wrote the main manuscript text. B.K., K.C. and A.K. recruited participants for the study. K.C. and A.K. conducted behavioral tests. B.K. performed spectroscopy and assessed the quality of spectra. B.K. and K.J. analyzed the data. B.K., P.B. and K.J. prepared the design of the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kossowski, B., Chyl, K., Kacprzak, A. et al. Dyslexia and age related effects in the neurometabolites concentration in the visual and temporo-parietal cortex. Sci Rep 9, 5096 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41473-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41473-x

This article is cited by

-

Association between urinary BTEX metabolites and dyslexic odds among school-aged children

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2024)

-

Metabolite differences in the medial prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia patients with and without persistent auditory verbal hallucinations: a 1H MRS study

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.