Abstract

In fishes, sonic abilities for communication purpose usually involve a single mechanism. We describe here the sonic mechanism and sounds in two species of boxfish, the spotted trunkfish Ostracion meleagris and the yellow boxfish Ostracion cubicus. The sonic mechanism utilizes a T-shaped swimbladder with a swimbladder fenestra and two separate sonic muscle pairs. Extrinsic vertical muscles attach to the vertebral column and the swimbladder. Perpendicularly and below these muscles, longitudinal intrinsic muscles cover the swimbladder fenestra. Sounds are exceptional since they are made of two distinct types produced in a sequence. In both species, humming sounds consist of long series (up to 45 s) of hundreds of regular low-amplitude pulses. Hums are often interspersed with irregular click sounds with an amplitude that is ten times greater in O. meleagris and forty times greater in O. cubicus. There is no relationship between fish size and many acoustic characteristics because muscle contraction rate dictates the fundamental frequency. We suggest that hums and clicks are produced by either separate muscles or by a combination of the two. The mechanism complexity supports an investment of boxfish in this communication channel and underline sounds as having important functions in their way of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent years have been marked by progress in the field of aquatic communication, notably increasing work on diversity of the acoustic communication at sea1,2 and the impact of anthropogenic sounds on fish populations3,4,5. Fish acoustic behavior is a prominent feature of coral-reef environments, and a wide variety of fishes produces specific courtship, spawning and agonistic sounds6,7. Coral reefs house approximately 50 fish families and about 30% of all fish species are able to produce sounds. On this basis, Lobel and colleagues nicely propose this biotope could be called “choral reef”7,8.

Boxfishes of the family Ostraciidae (Tetraodontiformes) occur in shallow tropical and warm seas of the world. The name stems from the body being almost completely encased in a bony shell or carapace formed of enlarged, thickened scale plates, usually hexagonal in shape, that are firmly sutured to one another9. The spotted trunkfish Ostracion meleagris Shaw, 1796 is a protogynous hermaphrodite species that is sexually dichromatic. Juveniles and females are uniformly dark brown with small white spots. The dorsal surface of males is black with white spots, but the flanks are blue with dark-edged orange-yellow spots on the side, and the belly is grey. This species is found in Indo-Pacific coral reefs, between the surface and 30 m depth10. Boxfishes are generally territorial with males defending groups of females. They tend to spawn after sunset11. The male approaches a female, and they both ascend with his snout against her back. Gamete release takes place when the pair lines up side by side, and both curl their caudal fins in opposite directions12. In the yellow boxfish Ostracion cubicus Linnaeus, 1758, males show brilliant yellow sides and a blue dorsal surface. Females are basically yellowish-brown10,13,14. Ostracion cubicus are also protogynous hermaphrodites and form harems of 2–4 females for each male. Mating behavior appears similar to O. meleagris, but further studies are required15.

Sounds have been recorded from this family. In the thornback cowfish Lactoria fornasini, high-pitched hums, although physically undescribed, are thought to help synchronizing spawning (Moyer 1979). In Ostracion meleagris, Lobel16 identified three different sounds. Spawning sounds have long durations (6 s) with peak energy between 215 and 270 Hz and are produced when a pair is in mating position. During competition for mates, males also produce “bump” sounds with a duration ranging from 9.9 to 10.6 ms and peak energy between 140 and 790 Hz. The third sound, the “buzz”16 is probably related to agonistic behavior17. It has peak energy between 198 and 535 Hz and durations of 130 to 209 ms.

Recent reviews have underlined the growing diversity of sound-producing mechanism in fishes2,18,19,20. Most mechanisms, resulting from evolutionary convergences, employ high-speed muscles (contraction rate between 50 and 300 Hz) that insert in part or totally on the swimbladder. In these species, the contraction rate dictates the fundamental frequency of the sounds21,22. The sound-producing mechanism of the Ostraciidae is not known. As in triggerfishes (Balistidae, Tetraodontiformes), the swimbladder is a voluminous elongated thick-walled dorsal sac with two anterior evaginated lateral lobes23. Fish and Mowbray proposed the use of sound- producing muscles related to the swimbladder and jaw teeth stridulation for the genus Lactrophrys, but they provide no evidence and did not describe the muscles. There is no indication for other genera of Ostraciidae such as Ostracion24. This study aims to examine for the first time the fish inner anatomy and sound features to infer the sonic mechanism in two boxfish species, Ostracion meleagris and Ostracion cubicus.

Material and Methods

Experimental procedures followed a protocol approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Liège. Ostracion meleagris and O. cubicus are not endangered or protected species, and specimens were not caught in protected areas at Moorea Island. All procedures were approved by the ethical commission of the University of Liège (ethics case 1759).

Biological material

A field campaign was conducted at the CRIOBE research station (www.criobe.pf) in Moorea Island (French Polynesia) between February and April 2016. Twenty-seven Ostracion meleagris from 3 to 9 cm in standard length (twelve males, eight females and seven juveniles) and five Ostracion cubicus adults (7 to 12 cm) were captured in the North Lagoon of Moorea. They were caught inside rocky crevices in the reef in water from 1 to 3.5 m depth using a gillnet (25 m long and mesh of 2.5 cm) and hand nets. Fish were stocked in two tanks (137 cm × 68 cm × 60 cm) with running seawater (28–29 °C) on a natural light cycle (12 h light:12 h dark). The tanks were equipped with aerators for oxygenation and stones and coral fragments as shelters. Fish were fed shrimp three times a week, but they also fed on algae on the stones. Barriers separated Ostracion meleagris in order to avoid fighting between males.

Morphological study

Nine O. meleagris (five males and four females) and one male O. cubicus were euthanized with an overdose of MS 222 (Sigma Aldrich). Three males and two females were fixed in 7% formalin for approximately two weeks before transfer to 70% ethanol. Swimbladders were dissected and examined with a Wild M10 (Leica) binocular microscope. A second lot of O. meleagris (four males and four females) was dissected to sample sound-producing muscles associated with the swimbladder. Muscle samples were immediately fixed in glutaraldehyde 2.5% in 0.1 cacodylate buffer pH 7.4, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through a graded ethanol-propylene oxide series and embedded in epoxy resin (SPI-PON 812, SPI-CHEM). Transverse semi-thin sections (1 µm) were cut using a diamond knife on a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome (Leica) and stained with toluidine blue (1%, pH 9.0) following the protocol of Richardson25, and photographed under a binocular microscope. Ultrathin sections (70–80 nm) were classically stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed using transmission electron microscopy with a TEM/STEM Tecnai G2 Twin (FEI) working at 200 kV accelerating voltage.

Sound recording

After an acclimation period of two days, fish were recorded with a hydrophone (HTI Min-96, sensitivity: −163.9 dB re 1 V μPa−1; flat frequency response range between 2 Hz and 30 kHz; Long Beach, MS, USA) placed in the center of the aquarium (98 × 47 × 48 cm) and connected to a Tascam DR-05 recorder (TEAC, Wiesbaden, Germany). Fish were hand held with the dorsal fin blocked in the tank approximately 3 cm from the hydrophone. Fish were held until sounds were obtained but sessions did not last more than three minutes. Different recordings of the same specimens were successively realized when necessary. Although handling has a level of artificiality, it does provoke fish to produce sounds as if they were captured by a predator26. This recording method was chosen because it elicits sounds from the same behavioral context, and it ensures that sounds are produced at the same distance from the hydrophone that was placed in the same part of the tank in order to avoid differences in signal loss27,28,29,30. Moreover, this distance also enables fish to remain within the attenuation distance31. With this methodology, feature variations within the sounds are due to the fish and not to environmental conditions. Ten sounds of each type were analyzed for each fish. After the recording, each fish was weighed and measured.

Sound analysis

Sound description is based on sounds from the 27 Ostracion meleagris and 5 Ostracion cubicus. Sounds were digitized at 44.1 kHz (16-bit resolution) and analyzed with AviSoft- SAS Lab Pro 5.2 software (Avisoft Bioacoustics, Glienicke, Germany). Recordings in small tanks induce potential artifacts because of reflections and tank resonance, and an estimated minimum resonant frequencies of 2360 Hz was calculated following Akamatsu et al.31. A band-pass filter (cutting frequencies: 0.05–2 kHz) was therefore applied to all recordings. Since calls are made of trains of pulses, the following temporal acoustic variables were manually measured on oscillograms: call duration (time from the beginning to the end of the sound, ms), pulse period (time between the onset of two consecutive pulses, ms), pulse duration (time from the beginning to the end of the pulse, ms) and the number of pulses in the sound. Spectral characteristics were obtained from power spectra [Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): 512 points, Hamming window, frequency resolution 4 Hz] after converting them to 4 kHz (16-bit resolution). Dominant frequency (frequency component with greatest energy, Hz) and its associated amplitude (sound pressure level in kPa at 3 cm) were measured.

Statistical analysis

Normality of data was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Acoustic features and biometric data (size and weight) were correlated by means of Spearman’s correlation tests. The characteristics of acoustic features in hums and click sounds within Ostracion meleagris (juveniles, females, males) were analyzed using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparison test for pairwise comparisons between categories. Due to low sample size, no intraspecific comparisons were made in O. cubicus. A t-test was used to compare acoustic features of hums and clicks between Ostracion meleagris and O. cubicus. Statistical analyses were carried out with R 3.0.2 or GraphPad (version 5, GraphPad software, Inc.).

Results

Morphology

The swimbladder is situated under the vertebral column in an area characterized by the fusion of several abdominal vertebrae with each other and to the skull, forming an osseous complex32. Therefore one can discern neural spines and some spinous processes, but the individual vertebral bodies are not clearly distinguishable. The anterior vertebral column is rod like, but posterior vertebrae show enlarged parapophyses (Fig. 1). The swimbladder is shaped like a large “T”: it is composed of a voluminous thick-walled dorsal sac with two prominent lateral anterior lobes (Fig. 1). Behind the lateral lobes, the anterior part of the swimbladder has a broad dorso-lateral area that is deprived of a tunica externa, forming a swimbladder fenestra. The fenestra is partly masked dorsally by the vertebral column that divides it in two equal parts (Fig. 1C). Moreover, two elongated pterygiophores originating from the anal fin form a vice on either side of the posterior swimbladder to which they are laterally attached with connective tissue (Fig. 1C).

Ostracion meleagris possess two pairs of sound-producing muscles that cross at right angles above the fenestra (Figs. 1 and 2). The superficial pair is extrinsic, originating on a tendon (Figs. 1A and 2A) that attaches to the dorsal side of the vertebral column. The muscles insert on the left and right ventral edges of the swimbladder just beyond the fenestra, and the muscle fibers run laterally. The deep pair is intrinsic to the swimbladder, running between the anterior and posterior vertical edges of the swimbladder fenestra. The muscle fibers run parallel to the long axis of the fish. Therefore, the longitudinal intrinsic muscles are perpendicular to the extrinsic sonic muscles and cover the swimbladder fenestra.

Histological sections and TEM views (Fig. 3) show many common characteristics in both muscles. They possess mitochondria of different sizes and are also characterized by a dense concentration of sarcoplasmic reticulum tubules: larger mitochondria occur mainly under the sarcolemma in the fiber periphery whereas smaller ones are distributed throughout the cell interspersed in myofibril-rich areas. In both case, they are generally close to sarcoplasmic reticulum that appear as tubule-rich areas just beneath the sarcolemma at the cell periphery or between fibril bundles. Cell morphology is however variable: some fibers show large spaces deprived of myofibrils and filled with sarcoplasmic reticulum while other cells showed myofibrils over the whole sectioned surface. Both muscles possess many nerve endings, and myelinated nerve sections are obvious on the semi-thin slices. They appeared as dark blue ring-shapes between the medium-blue fibers.

Toluidine blue-stained cross-sections of (A) the longitudinal intrinsic and (B) the transverse extrinsic sonic muscles in Ostracion meleagris. TEM cross-sections of (C) the longitudinal intrinsic and (D) the transverse extrinsic sonic muscles in Ostracion meleagris showing the central area (C) and the margin (D) of fibers. Deep blue dots around the cells (in A and B) correspond to the mitochondria; m: mitochondriae; mf, myofibril bundles; n: myelinated nerve; nu: nucleus; sr: sarcoplasmic reticulum tubules; s: sarcoplasm.

The spinal cord in the Ostraciidae ends abruptly forming a cord-like filum terminale within the first vertebra33. Both sound-producing muscles were innervated by different branches originating from the myelencephalon, close to the caudal cerebellum, and the spinal cord (Fig. 4). Three nerve roots innervate the muscles. Ventral branches originating from the true spinal nerve one (S1) innervates sonic muscles. They are also innervated by spinal nerves two (S2) and three (S3). S1 and S2 innervate the extrinsic sonic muscles whereas S3 innervate both muscle.

Dissections reveal a similar morphology in Ostracion cubicus.

Main sonic characteristics in Ostracion meleagris

Two sound types (hum and click) were simultaneously recorded from the 27 hand-held fish (Fig. 5). Fish produced the hum continuously and regularly although they were sometimes interspersed with clicks. Hums were found in all recordings, but clicks were sometimes missing and were never produced alone.

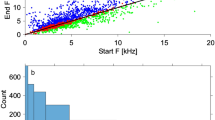

Hums consist of long trains of 661 ± 274 low-amplitude pulses (mean ± s.d.; 27 specimens, 270 sounds, TL: 30–91 mm). The pulse period within trains averaged 65 ± 10 ms, and hum duration (mean 46 ± 17 sec) correlated with the mean number of pulses (r2 = 0.84; Fig. 6). The dominant frequency of hum pulses was 146 ± 5 Hz (Fig. 7).

Clicks consist of isolated pulses that were produced irregularly and randomly during the hums. The boxfish emitted from one to more than 50 clicks during the hum although click sounds are not found in all the hums. The time between two clicks varied from 58 ms to 41 s, meaning there is no repeatable click period. Pulse duration was 45 ± 4 ms (mean ± s.d.; 23 specimens, 230 sounds), and the fundamental frequency was 172 ± 5 Hz. Click amplitudes (1.7 ± 0.6 kPa, n = 170) had more than 10 times the sound pressure of hum pulses (0.14 ± 0.1 kPa, n = 170), equivalent to an amplitude difference of 20 dB.

Intraspecific comparison of the calls in Ostracion meleagris

Fish weight correlated with standard length (r2 = 0.97, P < 0.001, n = 27) in juveniles, females and males (Fig. 8). Sound duration was 51 ± 17 s (n = 120) in males, 44 ± 18 s (n = 80) in females and 38 ± 10 s (n = 70) in juveniles (Table 1). However, no significant differences were found between the three groups for dominant frequency (KW, F2,25 = 2.22, P = 0.13), pulse period (F2,25 = 1.74, P = 0.19), sound duration (KW, F2,25 = 4.57, P = 0.1) and number of pulses (KW, F2,25 = 5.54, P = 0.06) for hums (Table 1).

However, there was a positive relationship between the fish length and both the call duration (rs = 0.61, p < 0.005) and number of pulses (rs = 0.61, p < 0.005). Fundamental frequency (rs = −0.23, p = 0.258) and pulse period (rs = −0.21, p = 0.294) did not change with fish size.

The click dominant frequency was significantly different between the three groups (KW, F2,950 = 168, P < 0.05). Post-hoc comparisons indicated juveniles (169 ± 10 Hz, n = 320) were significantly different (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05) from both males (173 ± 10 Hz, n = 290) and females (172 ± 11 Hz, n = 340). Similarly pulse duration was significantly shorter (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05) in juveniles (43 ± 1 ms, n = 358) than in males (45 ± 0.5 ms, n = 825) and females (44 ± 0.2 ms, n = 655). However, both dominant frequency (rs = 0.53, P < 0.001) and pulse duration (rs = 0.29, p < 0,001) increased with fish size. Males produce more clicks per hum than juveniles (Table 1).

Main sonic characteristics in Ostracion cubicus

Again hums and clicks were recorded within a sequence (Fig. 9). Clicks (12.3 ± 2.6 kPa, n = 247) had 40 times greater sound pressure (32 dB increase) than hums (0.1 ± 0.05 kPa, n = 430). Hums lasted 40 ± 8 s and were composed of 425 ± 142 pulses with a fundamental frequency of 152 ± 4 Hz. Sound duration was related to the number of pulses (r2 = 0.94). Clicks in Ostracion cubicus differ from Ostracion meleagris. They consist of short trains of 5 ± 1 pulses lasting 56 ± 8 ms, with a dominant frequency of 189 ± 4 Hz. Clicks in O. cubicus provided a more complex power spectrum than in O. meleagris (Fig. 7).

The comparison of acoustic characteristics between O. meleagris and O. cubicus showed hums and clicks features were all significantly different (t-test, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Sound producing mechanism

Different fish species can use a common mechanism to produce different sounds34,35,36. In most cases, differences result from temporal variation dictated by the firing pattern of vocal pacemaker neurons37,38. In mechanisms that involve the swimbladder, sound production is generally determined by contraction of a single pair of muscles2,18,19. However, in some species within the Ophidiidae or Carapidae for example, two or three pairs of muscles can be involved39,40,41,42,43. The combined action of these different muscles can produce different sounds types35,41,44,45. However, the ability to produce two distinct sounds simultaneously with two crossing muscles appears to be unique. The sonic muscles of swimbladder-associated sonic mechanisms are classically innervated by the occipital nerve or spinal nerves46,47,48. There is usually not a combination of spinal and occipital nerves, most probably because of the ontogenetic origin of the sonic muscles49. They can be derived from muscles associated with the cranium or from lateral trunk (body) muscles48,49 as in both boxfish species. It is worth mentioning several families of catfishes include species that can also use different kinds of mechanisms that produce markedly different sounds. It is however easier to associate sounds and mechanisms in this taxa because these catfish use the pectoral spine to produce stridulatory sounds50 and swimbladder to produce drumming sounds19,51,52. In different Scorpaeniformes species (Apistus and Pterois), intrinsic and extrinsic swimbladder muscles have been described53 but sounds are still to be recorded. Also extrinsic muscles originate on the skull and not on the vertebral column as in boxfish. The complexity of the boxfish supports an important investment in this communication channel and suggests sounds should have important functions in the biology of this taxa.

Sounds can be produced by superfast-contracting muscles2,21,54 whose contraction cycle provokes inward and outward movements of the swimbladder wall. This cause and effect relationships has been shown in the piranha Pygocentrus nattereri55 and the toadfish Opsanus tau21,56. In the study of acoustics of the swimbladder, the action of sonic muscles was mimicked by striking the swimbladder with a piezoelectric impact hammer57. These two movements, inward and outward, produced a negative and positive acoustic waveform, respectively. In O. meleagris, the oscillogram shape of the click sound is similar to the waveform resulting from the hammer strike in the toadfish (Fig. 10): a single rapid muscle twitch should create the click. In O. cubicus, the click call appears to be made of a train of successive cycles, indicating successive muscle contractions.

Waveform (A) of a sound induced by hammer strike in a male toadfish (Fine et al.57) and the waveform (B) of a click in Ostracion meleagris. Note the similarity between both sounds despite the swimbladder was excited in a different way. Displacement occurred over two cycles: an initial compression of the swimbladder (N1) followed by an expansion (P1) and a greatly attenuated second cycle (N2–P2) exhibiting rapid damping. The shape is inverted for the hum (C) where there is first a positive peak.

In the hums made by O. meleagris and O. cubicus, the pulse period corresponds to 65 ms (or 15 Hz) and 83 ms (or 12 Hz) respectively and not the dominant frequencies of 145 and 154 Hz respectively. Therefore the pulse period does not correspond to the muscle contraction rate. However, a deeper examination of hum pulses in the oscillogram reveals they can be made of 1 to 5 cycles having a period between 5 (200 Hz) and 8.5 ms (117 Hz) (Fig. 5D), which is close to the dominant frequency values. Therefore each pulse within the hums could result from regular packs of one to five muscle contractions (Fig. 5D). The waveform of the hum differs however from that of the click. Different hypotheses can be formulated. First, contraction amplitude is likely low in the hum causing shorter displacements of the swimbladder and weaker sounds. Second, the fast successive muscle contractions mask the end of individual hum cycles.

In the framework of this study, two different muscles work sequentially to produce a specific distress call consisting of hums and clicks. The muscles that produce the hum works for a long period of time (up to 130 seconds in this study!) and would be fatigue resistant. The click muscles have less sustained but more powerful contractions resulting in a greater amplitude sound than in the hums. Histological sections of fast sound-producing muscles show a common design: mitochondria are abundant in a large band of sarcoplasm in the fiber periphery, and a central core of sarcoplasm can be found in some but not all cases51,58,59,60. In O. meleagris, sonic muscles do not follow this scheme completely since large space devoted to sarcoplasm was not observed in all fibers. They are however characterized by an expanded development of sarcoplasmic reticulum and a low density of myofibrils that are related to fast contraction since the relative percentage by volume of myofibrils is inversely proportional to the speed and directly proportional to force61. The high concentration of sarcoplasmic reticulum is related to the ability to release and remove rapidly Ca2+ from the contraction site62. Ultrastructure and sound waveforms therefore support that both muscle pairs contract rapidly since dominant frequency is in the same order of magnitude in hums and clicks (146 vs 172 Hz).

Because we were unable to highlight qualitative differences between both muscles, we cannot support the association between a given muscle and a corresponding sound. We however have to suggest an alternate hypothesis. There is an overlapping innervation of intrinsic and extrinsic muscles meaning a click could result from the simultaneous contractions of both sonic muscles. The combined contraction would drive larger swimbladder movements and provoke louder sounds than each muscle separately. In this case, trains of contraction would produce the hum and the additional contraction of the second muscle would provoke the click. Physiological experiments are necessary to test our hypothesis.

Acoustic signals

Of the three previously described sounds in O. meleagris16, only the spawning sound shares similarity with the hum because both are of long duration (>1000 ms). However, Lobel (1996) did not describe two sound types produced within a sequence. This difference may relate to the behavioral context in which sounds were recorded. Sounds in the previous study were recorded in the field during the reproduction period16. In the present study, fish were held by hand and recorded in a tank. In this situation, the behavior is usually associated with distress63,64. The two studies suggest a large sonic repertoire and supports the importance of acoustic communication in the Ostraciidae.

Two sound types were recorded within the same sequences: hums occur with sporadic clicks. These clicks are short (45 ms), have a dominant frequency of 172 Hz and are produced irregularly with a pulse period between 58 ms and 41 s. Clicks were thus irregular and would appear to result from isolated contractions rather than a repeated motor pattern. Hums however are long (ca 46 s), can possess hundreds of pulses and are regularly produced with a period between 40 and 90 ms. Therefore hums consist of trains of pulses produced by rhythmic neuronal firing38,49,65. Additionally, clicks have at least 10 fold greater amplitude (linear units) than hums in both species.

Intraspecific differences

The hypothesized sound production mechanism in Ostracion species is supported by the intraspecific sonic characteristics in O. meleagris. In teleosts, sonic characteristic can vary with fish sex and size66,67. The amplitude variation is mainly related to the sound-producing mechanism. In species in which the muscle contraction rate determines the fundamental frequency, variations between specimen size or sex has little effect on timing of sonic muscle contraction and hence sound characteristic since it depends mainly on muscle twitch parameters18. In other words, in fish using fast muscles, the size can have a mathematical influence on the sound characteristics but the fish would not be able to distinguish such minor variation in frequencies29,68,69. In O. meleagris, fish size correlates with weight and separates into three classes: male, female and juvenile. Males (SL = 7.9 cm) are bigger than females (SL = 6.9 cm), both being obviously bigger than juveniles (SL = 3.8 cm). However, this size difference is not related to the dominant frequency, which differentiates only from 1 to 4 Hz (Table 1). In comparison, the difference would be about 400 Hz in pomacentrids with the same size variation67. Therefore dominant frequency does not provide information about the size or the sex in O. meleagris. The small differences between fishes having different sizes would be related to a scaling effect: longer muscles from larger fish takes longer to complete a twitch, providing lower frequencies18,68. In the same way, pulse duration does not provide intraspecific information. Similarly dominant frequency and pulse period of hum pulses did not differ between males, females and juveniles. If the expected status of distress call use to startle a predator or warn conspecifics can be confirmed, high intraspecific information content is not needed here. However, the sound duration indicated intraspecific differences since male sounds were longest (51 s), followed by females (44 s) and then juveniles (38 s).

References

Ruppé, L. et al. Environmental constraints drive the partitioning of the soundscape in fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 6092–6097 (2015).

Fine, M. L. & Parmentier, E. Mechanisms of fish sound production. In Sound Communication in Fishes. (ed. Ladich, F.) 77–126 (Springer, 2015).

Slabbekoorn, H. et al. A noisy spring: The impact of globally rising underwater sound levels on fish. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 419–427 (2010).

Picciulin, M., Sebastianutto, L., Codarin, A., Calcagno, G. & Ferrero, E. A. Brown meagre vocalization rate increases during repetitive boat noise exposures: a possible case of vocal compensation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 132, 3118–3124 (2012).

Vasconcelos, R. O., Amorim, M. C. P. & Ladich, F. Effects of ship noise on the detectability of communication signals in the Lusitanian toadfish. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 2104 LP–2112 (2007).

Tricas, T. C. & Boyle, K. S. Acoustic behaviors in Hawaiian coral reef fish communities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 511, 1–16 (2014).

Lobel, P. S., Kaatz, I. M. & Rice, A. N. Acoustic behaviour of coral reed fish. In Reproduction and sexuality in marine fishes: patterns and procesess (ed. Cole, K. S.) 307–386 (University of California Press, 2010).

Lobel, P. S. The “Choral Reef”: the ecology of underwater sounds. In Joint International Scientific Diving Symposium AAUS & ESDP. (eds Lang, M. A. & Sayer, M.) 179–184 (2013).

Matsuura, K. Taxonomy and systematics of tetraodontiform fishes: a review focusing primarily on progress in the period from 1980 to 2014. Ichthyol. Res. 62, 72–113 (2015).

Myers, R. F. Micronesian Reef Fishes. (Coral Graphics, 1999).

Sancho, G., Solow, A. R. & Lobel, P. S. Environmental influences on the diel timing of spawning in coral reef fishes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 206, 193–212 (2000).

Sancho, G. Factors regulating the height of spawning ascents in trunkfishes (Ostraciidae). J. Fish Biol. 53, 94–103 (1998).

Cornic, A. Poissons de l’Ile Maurice. (1987).

Debelius, H. Guide du Récif Corallien. Mer Rouge. (PLB Editions, 1998).

Moyer, J. T. Mating strategies and reproductive behavior of ostraciid fishes at Miyake-jima, Japan. Japanese J. Ichthyol. 26, 148–160 (1979).

Lobel, P. S. Spawning sound of the trunkfish, Ostracion meleagris (Ostraciidae). Biol. Bull. 191, 308–309 (1996).

Mann, D. & Lobel, P. S. Acoustic behaviour of the damselfish Dascyllus albisella: behavioural and geographic variation. Environ. Biol. Fishes 51, 421–428 (1998).

Parmentier, E. & Fine, M. L. Fish sound production: insights. In Vertebrate sound production and acoustic communication. (eds Suthers, R., Tecumseh, F., Popper, A. N. & Fay, R. R.) 19–49 (Springer, 2016).

Ladich, F. & Fine, M. L. Sound generating mechanisms in fishes: a unique diversity in vertebrates. In Communication in Fishes. (eds Ladich, F., Collin, S. P., Moller, P. & Kapoor, B. G.) 3–34 (Science Publishers, 2006).

Parmentier, E. & Diogo, R. Evolutionary trends of swimbladder sound mechanism in some teleost fishes. In Communication in Fishes. (eds Ladich, F., Collin, S. P., Moller, P. & Kapoor, B. G.) 45–70 (Science Publishers, 2006).

Fine, M. L., Malloy, K. L., King, C., Mitchell, S. L. & Cameron, T. M. Movement and sound generation by the toadfish swimbladder. J. Comp. Physiol. - A Sensory, Neural, Behav. Physiol. 187, 371–379 (2001).

Fine, M. L., King, T. L., Ali, H., Sidker, N. & Cameron, T. M. Wall structure and material properties cause viscous damping of swimbladder sounds in the oyster toadfish Opsanus tau. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283, 20161094 (2016).

Chanet, B., Guintard, C. & Lecointre, G. The gas bladder of puffers and porcupinefishes (Acanthomorpha: Tetraodontiformes): Phylogenetic interpretations. J. Morphol. 275, 894–901 (2014).

Fish, M. P. & Mowbray, H. M. Sounds of Western North Atlantic Fishes (The Johns Hopkins Press, 1970).

Richardson, K. C., Jarett, L. & Finke, E. H. Embedding in epoxy resins for ultrathin sectioning in electron microscopy. Stain Technol. 35, 313–323 (1960).

Oliveira, T. P. R., Ladich, F., Abed-Navandi, D., Souto, A. S. & Rosa, I. L. Sounds produced by the longsnout seahorse: a study of their structure and functions. J. Zool. 294, 114–121 (2014).

Millot, S. & Parmentier, E. Development of the ultrastructure of sonic muscles: a kind of neoteny? BMC Evol. Biol. 14, 1–9 (2014).

Markl, H. Schallerzeugung bei Piranhas (Serrasalminae, Characidae). Z. Vgl. Physiol. 74, 39–56 (1971).

Parmentier, E., Vandewalle, P., Brié, C., Dinraths, L. & Lecchini, D. Comparative study on sound production in different Holocentridae species. Front. Zool. 8, 12 (2011).

Parmentier, E., Boyle, K. S., Berten, L., Brié, C. & Lecchini, D. Sound production and mechanism in Heniochus chrysostomus (Chaetodontidae). J. Exp. Biol. 214, 2702–2708 (2011).

Akamatsu, T., Okumura, T., Novarini, N. & Yan, H. Y. Empirical refinements applicable to the recording of fish sounds in small tanks. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 112, 3073–3082 (2002).

Klassen, G. J. Phylogeny and biogeography of the Ostraciinae (Tetraodontiformes: Ostraciidae). Bulletin of Marine Science 57, 393–441 (1995).

Uehara, M., Hosaka, Y. Z., Doi, H. & Sakai, H. The shortened spinal cord in tetraodontiform fishes. J. Morphol. 276, 290–300 (2015).

Parmentier, E., Lecchini, D. & Mann, D. A. Sound production in damselfishes. In Biology of damselfishes. (eds Frédérich, B. & Parmentier, E.) 204–228 (CRC Press, Taylor & Francis, 2016).

Parmentier, É., Colleye, O. & Lecchini, D. New insights into sound production in Carapus mourlani (Carapidae). Bull. Mar. Sci. 92 (2016).

Onuki, A. & Somiya, H. Two types of sounds and additional spinal nerve innervation to the sonic muscle in John Dory, Zeus faber (Zeiformes: Teleostei). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 84, 843–850 (2004).

Bass, A. H. & Baker, R. Sexual dimorphisms in the vocal control system of a teleost fish: morphology of physiologically identified neurons. J. Neurobiol. 21, 1155–1168 (1990).

Bass, A. H. & McKibben, J. R. Neural mechanisms and behaviors for acoustic communication in teleost fish. Prog. Neurobiol. 69, 1–26 (2003).

Parmentier, E., Bouillac, G., Dragicevic, B., Dulcic, J. & Fine, M. Call properties and morphology of the sound-producing organ in Ophidion rochei (Ophidiidae). J. Exp. Biol. 213, 3230–3236 (2010).

Kéver, L. et al. Sexual dimorphism of sonic apparatus and extreme intersexual variation of sounds in Ophidion rochei (Ophidiidae): first evidence of a tight relationship between morphology and sound characteristics in Ophidiidae. Front. Zool. 9–34 (2012).

Kéver, L. et al. Sound production in Onuxodon fowleri (Carapidae) and its amplification by the host shell. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 4283–4294 (2014).

Rose, J. A. Anatomy and sexual dimorphism of the swim bladder and vertebral column in Ophidion holbrooki (Pisces: Ophidiidae). Bull. Mar. Sci. 11, 280–308 (1961).

Ali, H. A., Mok, H.-K. & Fine, M. L. Development and sexual dimorphism of the sonic system in deep sea neobythitine fishes: The upper continental slope. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 115, 293–308 (2016).

Parmentier, E., Lagardère, J. P., Chancerelle, Y., Dufrane, D. & Eeckhaut, I. Variations in sound-producing mechanism in the pearlfish Carapini (Carapidae). J. Zool. 276, 266–275 (2008).

Parmentier, E., Bahri, M. A., Plenevaux, A., Fine, M. L. & Estrada, J. M. Sound production and sonic apparatus in deep-living cusk-eels (Genypterus chilensis and Genypterus maculatus). Deep Sea Res. Part I 141, 83-92 (2018)

Carlson, B. A. & Bass, A. H. Sonic/vocal motor pathways in squirrelfish (Teleostei, Holocentridae). Brain. Behav. Evol. 56, 14–28 (2000).

Yoshimoto, M., Kikuchi, K., Yamamoto, N., Somiya, H. & Ito, H. Sonic motor nucleus and its connections with octaval and lateral line nuclei of the medulla in a rockfish, Sebastiscus marmoratus. Brain. Behav. Evol. 54, 183–204 (1999).

Onuki, A. & Somiya, H. Innervation of sonic muscles in teleosts: occipital vs. spinal nerves. Brain Behav. Evol. 69, 132–141 (2007).

Bass, A. H., Chagnaud, B. P. & Feng, N. Y. Comparative neurobiology of fishes. In Sound Communication in Fishes. Animal Signals and Communication. (ed. Ladich, F.) 35–75 (Springer, 2015).

Parmentier, E. et al. Functional study of the pectoral spine stridulation mechanism in different mochokid catfishes. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 1107–1114 (2010).

Ladich, F. Sound-generating and -detecting motor system in catfish: design of swimbladder muscles in doradids and pimelodids. Anat. Rec. 263, 297–306 (2001).

Ladich, F. Comparative analysis of swimbladder (drumming) and pectoral (stridulation) sounds in three families of catfishes. Bioacoustics 8, 185–208 (1997).

Yabe, M. Comparative osteology and myology of the superfamily Cottoidea (Pisces: Scorpaeniformes) and its phylogenetic classification. 32: 1–130. Mem. Fac. FIisheries, Hokkaido Univ. 32, 1–130 (1985).

Young, I. S. & Rome, L. C. Mutually exclusive muscle designs: the power output of the locomotory and sonic muscles of the oyster toadfish (Opsanus tau). Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268, 1965–1970 (2001).

Millot, S., Vandewalle, P. & Parmentier, E. Sound production in red-bellied piranhas (Pygocentrus nattereri, Kner): an acoustical, behavioural and morphofunctional study. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3613–3618 (2011).

Tavolga, W. N. Review of marine bio-acoustics, state of the art (1964).

Fine, M. L., King, C. B. & Cameron, T. M. Acoustical properties of the swimbladder in the oyster toadfish Opsanus tau. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 3542–3552 (2009).

Fine, M. L., Bernard, B. & Harris, T. M. Functional morphology of toadfish sonic muscle fibers: relationship to possible fiber division. Can. J. Zool. 71, 2262–2274 (1993).

Boyle, K. S., Riepe, S., Bolen, G. & Parmentier, E. Variation in swim bladder drumming sounds from three doradid catfish species with similar sonic morphologies. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 2881–2891 (2015).

Boyle, K. S., Bolen, G. & Parmentier, E. Agonistic sounds and swim bladder morphology in a malapterurid electric catfish. J. Zool. 296, 249–260 (2015).

Rome, L. C., Syme, D. A., Hollingworth, S., Lindstedt, S. L. & Baylor, S. M. The whistle and the rattle: the design of sound producing muscles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 8095–8100 (1996).

Feher, J., Waybright, T. & Fine, M. Comparison of sarcoplasmic reticulum capabilities in toadfish (Opsanus tau) sonic muscle and rat fast twitch muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 19, 661–674 (1998).

Ladich, F. & Myrberg, A. A. J. In Communication in fishes. (eds Ladich, F., Collin, S. P., Moller, P. & Kapoor, B. G.) 122–148 (Science Publishers, 2006).

Ladich, F. Agonistic behaviour and significance of sounds in vocalizing fish. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 29, 87–108 (1997).

Bass, A. H. & Ladich, F. Vocal acoustic communication: from neurons to behaviour. In Fish Bioacoustics. (eds Popper, A. N., Fay, R. R. & Webb, J. F.) 253–278 (Springer, 2008).

Fine, M. L. & Waybright, T. D. Grunt variation in the oyster toadfish Opsanus tau: effect of size and sex. PeerJ 3, e1330 (2015).

Colleye, O., Frederich, B., Vandewalle, P., Casadevall, M. & Parmentier, E. Agonistic sounds in the skunk clownfish Amphiprion akallopisos: size-related variation in acoustic features. J. Fish Biol. 75, 908–916 (2009).

Connaughton, M. A., Taylor, M. H. & Fine, M. L. Effects of fish size and temperature on weakfish disturbance calls: implications for the mechanism of sound generation. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 1503–1512 (2000).

Mélotte, G., Vigouroux, R., Michel, C. & Parmentier, E. Interspecific variation of warning calls in piranhas: a comparative analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 36127 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from the Fonds De La Recherche Scientifique - FNRS [T.0056.13 to E.P.] and by a grant from PSL Environnement (project: Pesticor), LabEx CORAIL (project: Etape) awarded to DL. We are grateful to M. Bournonville, C. Michel and the team of the Aquarium-Museum of Liège (Belgium) for helping with maintenance of some specimens.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.P. and D.L. designed the experiments. L.S. carried out the first experiments and analysed the data with the help of F.B., M.F. and X.R. The analysis of the sound producing mechanism has been realised by E.P. and M.N. whereas P.C. and S.S. have worked on the histology. E.P. made the drawings. E.P. and M.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parmentier, E., Solagna, L., Bertucci, F. et al. Simultaneous production of two kinds of sounds in relation with sonic mechanism in the boxfish Ostracion meleagris and O. cubicus. Sci Rep 9, 4962 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41198-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41198-x

This article is cited by

-

Global inventory of species categorized by known underwater sonifery

Scientific Data (2023)

-

Fish sounds of photic and mesophotic coral reefs: variation with depth and type of island

Coral Reefs (2023)

-

Male territory-visiting polygamy of the white-spotted boxfish Ostracion meleagris (Ostraciidae) involving daily spawning migration

Environmental Biology of Fishes (2022)

-

Local sonic activity reveals potential partitioning in a coral reef fish community

Oecologia (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.