Abstract

There is currently an epidemic of opioid use, overdose, and dependence in the United States. Although opioid dependence (OD) is more prevalent in men, opioid relapse and fatal opioid overdoses have recently increased at a higher rate among women. Epigenetic mechanisms have been implicated in the etiology of OD, though most studies to date have used candidate gene approaches. We conducted the first epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) of OD in a sample of 220 European-American (EA) women (140 OD cases, 80 opioid-exposed controls). DNA was derived from whole blood samples and EWAS was implemented using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylationEPIC array. To identify differentially methylated CpG sites, we performed an association analysis adjusting for age, estimates of cell proportions, smoking status, and the first three principal components to correct for population stratification. After correction for multiple testing, association analysis identified three genome-wide significant differentially methylated CpG sites mapping to the PARG, RERE, and CFAP77 genes. These genes are involved in chromatin remodeling, DNA binding, cell survival, and cell projection. Previous genome-wide association studies have identified RERE risk variants in association with psychiatric disorders and educational attainment. DNA methylation age in the peripheral blood did not differ between OD subjects and opioid-exposed controls. Our findings implicate epigenetic mechanisms in OD and, if replicated, identify possible novel peripheral biomarkers of OD that could inform the prevention and treatment of the disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lifetime U.S. prevalence of opioid dependence (OD) is 0.3% and of opioid abuse, 1.1%1. These result in an estimated annual cost of $78.5 billion2. Further, opioids are the single greatest cause of accidental fatal overdose in the United States3,4,5,6, which until recently was mainly caused by heroin and prescription opioid pain relievers. However, recent data show fentanyl emerging as a major problem7. In the United States, OD and opioid abuse have become an epidemic8 and fatal opioid overdoses have quadrupled in recent years9.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been widely used to identify genetic factors that predispose to drug dependence10. GWASs from our lab have identified risk variants for OD; the most compelling implicated potassium and calcium signaling11, and more recently, RGMA, the gene that encodes repulsive guidance molecule A, a central nervous system axon guidance protein12. However, because these associations account for only a small proportion of the known heritability, additional mechanisms are certainly involved in the risk for OD.

Epigenetic mechanisms, which underlie some of the interplay between environmental factors and genes, are implicated in drug abuse risk. Several studies have shown that DNA methylation, the most studied epigenetic mechanism in humans, is altered by opioid abuse or dependence. Overall methylation in peripheral blood DNA is greater in OD subjects than controls13. Candidate epigenetic studies at the OPRM1 gene have shown that increased DNA methylation at this locus is associated with OD, based on whole blood cells13,14,15,16 and brain tissue17. A study from our lab examining 16 CpGs in the OPRM1 promoter region showed that three closely mapped CpGs within the promoter are hypermethylated in cases with comorbid AD and OD compared to controls18.

However, these studies have yielded inconsistent findings19 and have mostly been performed in men. Women are 48% more likely than men to use prescription drugs and to be prescribed opioids, so it is particularly important for studies of these traits to include females. Further, very few studies to date have examined genome-wide DNA methylation changes associated with substance dependence and no methylation studies have evaluated OD specifically. There has been one small (n = 48) genome-wide DNA methylation study of methadone dose20.

We examined genome-wide DNA methylation changes associated with OD in a population of European-American (EA) women to identify peripheral biomarkers that can inform preventive and treatment strategies for the disorder.

Materials and Methods

Sample

The study sample consisted of 220 EA women (mean age = 40 ± 13.5 years) recruited at two clinical sites: Yale University School of Medicine (APT Foundation, New Haven, CT), and the University of Connecticut Health Center (Farmington, CT). The participants were selected from a sample of approximately 13,000 individuals recruited in the course of our NIH-funded studies of the genetics of alcohol and drug dependence11,21,22,23. The study was approved by the Yale Humans Investigation Committee, and research was performed following their guidelines. All subjects provided written informed consent, and certificates of confidentiality were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

Subjects were interviewed using the Semi-Structured Assessment for Drug Dependence and Alcoholism (SSADDA), a polydiagnostic assessment for psychiatric traits used to derive a diagnosis of DSM-IV OD12. All subjects were opioid exposed (based on self-reported lifetime opioid use >10 times). The sample consisted of 140 OD cases and 80 opioid-exposed controls. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Polydrug use, that is, the prevalence of more than one substance dependence diagnosis, is present in 74% of the sample; 95.7% in OD cases and 36.3% in opioid-exposed controls. AD is present in 41.8% and cocaine dependence (CocD) is present in 61.8% of the sample. Among opioid-exposed controls, 23.7% are AD subjects and 31.3% are CoCD subjects. Among OD cases, 52.1% are AD subjects, and 79.3% are CoCD subjects.

Genomic DNA extraction, Bisulfite Modification, Methylation Array

Genomic DNA (500 ng) was extracted from whole blood using PAXgene Blood DNA kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and standard procedures. Genomic DNA (500 ng) was treated with bisulfite reagents using a EZ-96 DNA methylation kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Bisulfite-converted DNA samples were used in the array-based genome-wide DNA methylation assay. Methylation status was assessed using the Illumina Infinium Human MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), which interrogates DNA methylation >800,000 loci across the genome at single-nucleotide resolution.

Quality Control and Normalization

Genome-wide DNA methylation assays were conducted at the Yale Center for Genome Analysis. GenomeStudio software (Illumina) was used to generate β values for each CpG site; β values were defined as M/(M + U + α), where M is the total methylated signal and U the total unmethylated signal, ranging from 0.0 to 1.0, with α = 100 added to stabilize beta values when both M and U are small.

Quality control was performed based on a pipeline using the ‘minfi’ R package (Bioconductor 1.8.9)24. CpG sites with detection p-value > 0.001 were removed to ensure that only high-confidence probes were included. Probes with annotated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at single-base extension (SBE/CPG) sites (via the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database 137 [National Center for Biotechnology Information]) or mapped to multiple places in the genome or to sex chromosomes were also excluded. Combat method in the ‘sva’ package25 was applied to correct for batch effects associated with sample plate and cohort group. Functional normalization was conducted using the “Preprocessfunnorm” function in the ‘minfi’ R package24, which uses internal control probes present on the array to control for between-array technical variation, thereby outperforming other approaches26. Density plots were generated to evaluate the distribution of beta (β) values before and after functional normalization (Supplementary Fig. 1). After quality control and normalization, a total of 790,677 CpG sites (91% of possible sites) were left for subsequent analysis.

Because methylation values at CpG sites can be cell-type specific27, we conducted a cell composition analysis following a published method28. The relative proportion of each cell type in our heterogenous peripheral blood samples was estimated by implementing the ‘minfi’ function “estimateCellCounts” from the R package ‘Flow-Sorted.Blood.450k’24.

To adjust for possible population stratification within the EA subjects, a methylation-based principal component (PC) approach was conducted based on sets of CpG sites within 50 kb of SNPs using the 1000 Genomes Project variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.129.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed within R 3.4.0 (www.r-project.org). To identify differentially methylated CpG sites associated with OD, EWAS was conducted using the ‘cpg.assoc’ function from the ‘minfi’ R package30, adjusting for age, estimated cell proportions (i.e., CD8T, CD4T, NK, C cells, monocytes and granulocytes), and the first three population stratification PCs. Given the broad impact of smoking on DNA methylation across the genome31 and the comorbidity of OD with smoking behavior, we also adjusted for smoking status. We used Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple testing (p value for significance set at 5.9 × 10−8).

Methylation Quantitative Trait Loci Analysis

Methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTL) analysis was conducted to examine whether methylation patterns at GWS CpG sites interacted with genotype variation. Genotype data were available for 141 subjects included in the EWAS analysis. Genotype information, imputation, and quality control information is provided in our recent OD GWAS12. SNPs within 1 MB of the CpG site (hg19 reference genome) were included in the meQTL analysis. We conducted a linear regression analysis using PLINK 1.932 adjusting for the same covariates as in the EWAS. Analyses were performed separately based on the genotyping array (these included the HumanOmni1-Quad v1.0 and the HumanCore Exome array, both from Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) and then combined by meta-analysis using the inverse variance method implemented in PLINK 1.9. meQTL analysis were also conducted in OD cases (n = 121) and opioid-exposed controls (n = 29), separately.

Estimated Epigenetic Age

Methods are described in the Supplementary section.

Results

Epigenome-wide association analysis

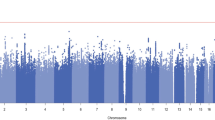

Three CpG sites were genome-wide significant (GWS) after Bonferroni correction (p < 5.9 × 10−8). Table 2 lists the top 10 differentially methylated CpG sites associated with OD in EA women. A Manhattan plot is shown in Fig. 1. Supplementary Figure 2 illustrates the quantile-quantile (QQ) plot for the p-values of the association between DNA methylation and OD. There was no evidence of inflation (λ = 1.00).

All three of the GWS differentially methylated CpG sites showed decreased DNA methylation in OD subjects (Fig. 2). The top GWS CpG site identified was cg17426237 (chr 10:51463156, p = 6.77 × 10−9) located within the poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) gene. The other two GWS differentially methylated CpG sites were cg21381136 (RERE; “arginine-glutamic acid dipeptide repeats”; chr1:8445818; p = 2.75 × 10−8), and cg18177613 (CFAP77; “cilia and flagella associated protein 77”; chr9:135359969; p = 5.89 × 10−8). Functional annotation of the GWS CpGs showed that two sites were located in the gene body (cg21381136 and cg18177613) and one in the 5′UTR region (cg21381136). Further, cg21381136 is an enhancer and cg18177613 has three DNase hypersensitivity sites, an indicator of open chromatin. DNA methylation patterns in whole blood and multiple brain regions for cg17426237 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Gene expression patterns in blood and multiple brain tissues for PARG and RERE are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Violin plots of genome-wide significant (GWS) CpG sites associated with opioid dependence (OD). DNA methylation levels (beta values) of GWS CpG sites associated with OD are shown: (A) cg17426237 (PARG gene), (B) cg21381136 (RERE gene), and (C) cg18177613 (CFAP77 gene) in opioid-exposed controls and OD cases. All CpG sites showed hypomethylation associated with OD. *Represents GWS threshold of p < 5.9 × 10−8.

Three other differentially methylated CpG sites were near GWS: cg23095642 located at OSBPL9 (“Oxysterol binding protein-like 9”), cg04983519 at EHMT2 (“euchromatin histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2”), and cg11395372 at TUBA1C (“tubulin alpha 1c”) (Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis

OD subjects have a higher rate of other substance use disorders, including AD and CoCD, than controls. To account for the differences in AD and CocD prevalence between cases and controls, we included these two diagnoses as covariates along with age, cell type proportion, the first three PCs and smoking status for the GWS CpG sites. After adjusting for AD and CocD, associations of PARG, RERE, and CFAP77 CpG sites with OD slightly decreased (p = 8.01 × 10−9, 3.69 × 10−8, and 3.45 × 10−7, respectively). The magnitudes of the effects of these variables, as well as current smoking, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

DNA methylation levels at these CpG sites were also associated with OD related traits such as OD symptom count (cg17426237, p = 0.0005; cg21381136, p = 0.0027; cg18177613, p = 0.0021; Fig. 3A–C), and longest duration of chronic opioid use (cg17426237, p = 0.0001; cg18177613, p = 0.0204; Fig. 3J,L). A trend-level possible association was also observed for the duration of opioid use (cg17426237, p = 0.0565; Fig. 3G), and longest duration of chronic opioid use (cg21381136, p = 0.0742; Fig. 3K). No association was observed with OD age of onset. Significant associations between DNA methylation at these CpG sites and OD-related traits are in the same direction as with OD: DNA hypomethylation at these CpG sites is associated with OD. In this dataset, OD status correlates with OD symptoms (n = 218, 2 missing values, p < 0.0001), duration of opioid use (n = 217, 3 missing values, p < 0.0001), and longest duration of chronic opioid use (n = 218, 2 missing values, p < 0.0001), but not with OD age of onset (n = 120, OD cases only, p = 0.9048).

Association between genotype data at rs2611513 and DNA methylation levels at GWS CpG site cg17426237. rs2611513 associated with DNA methylation levels at cg17426237; C allele associated with lower DNA methylation in (A) all sample (n = 141, p = 0.025), and (B) OD cases (n = 112; p = 0.042). No association was obtained in (C) opioid-exposed controls (n = 29; NS). *Represents p < 0.05.

meQTL analysis

After meta-analysis, a SNP (rs2611513) mapped to PRKG1 was nominally significant in association with methylation patterns of cg17426237 at PARG (n = 141, p = 0.025; Fig. 4A). This SNP was nominally significant (β = 0.17, p = 0.02) in our most recent EA OD GWAS12. The risk allele (C) for OD at rs261151333 was associated with decreased methylation at cg17426237. In the OD EWAS, cg17426237 also showed lower methylation. To determine whether the SNP is also a meQTL in OD cases and opioid-exposed controls considered separately, we further correlated the genotype of rs2611513 with cg17426237 in subset samples of cases and controls. We found that rs2611513 genotype was nominally significant in association with methylation patterns of cg17426237 at PARG gene in OD cases (n = 121, p = 0.042; Fig. 4B). In opioid-exposed controls, no association was observed, possibly due to limited power from the small sample size (n = 29; Fig. 4C).

Association between genome-wide significant (GWS) CpG sites and opioid dependence (OD)-related traits. DNA methylation (beta values) of GWS CpG sites associated with OD-related traits are shown: (A–C) OD symptoms, (D–F) age of onset (years), (G–I) duration of opioid use (years), (J–L) longest duration of chronic opioid use (years). Significant threshold is set at p < 0.05.

Estimated epigenetic age in the peripheral blood of OD subjects and opioid-exposed controls

As expected, chronological age was significantly correlated with methylation age (DNAm Age) (r = 0.93, p < 0.0001) in the full sample of 220 subjects (Supplementary Fig. 6A). No significant differences were observed in the age acceleration residual between OD subjects and opioid-exposed controls (Supplementary Fig. 6B).

Discussion

This is the first epigenome-wide association study of OD. After correction for multiple testing, we identified three GWS CpG sites in EA women, which map to PARG, RERE, and CFAP77 – genes implicated in chromatin remodeling, DNA binding, cell survival, and cell projection. Among these, one CpG site showed a significant association with a cis-genetic variant. The results support the interpretation that DNA methylation differences could be attributable to both environmental and genetic influences.

Our top GWS CpG site, cg17426237, is located in the PARG gene. The protein product of this gene is a catabolic enzyme of poly (ADP-ribose), involved in various cellular processes including DNA repair, transcription, and the modulation of chromatic structure. Methylation of this CpG site also occurs in brain tissue across multiple brain regions (Supplementary Fig. 3). PARG gene is highly expressed in human brain (Supplementary Fig. 4A), with its highest expression in cerebellar tissue.

The second top GWS CpG site identified, cg21381136, maps to the RERE gene, which is also highly expressed in brain (Supplementary Fig. 4B). SNPs at this locus have been identified in GWASs of schizophrenia33,34,35 and in the cross-disorders analysis from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, which included autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder33; and educational attainment36. The encoded protein (RERE) is involved in transcriptional repression during embryonic development, chromatin remodeling, and cell survival. RERE interacts with EHMT237, also known as G9A, a histone methyltransferase involved in transcriptional repression. A CpG site at EHMT2, cg04983519, is among the top 10 differentially methylated CpG sites associated with OD identified herein. Considered together, these results implicate the gene regulation pathway.

A third GWS CpG site that we identified, cg18177613, is located at the CFAP77 gene, involved in cell projection and protein binding. The association of the GWS CpG sites identified with OD appears to be mostly independent of comorbid AD and CocD in OD subjects compared to opioid-exposed controls. Further, DNA methylation at these CpG sites is also associated with OD-related traits such as OD symptom count and longest duration of chronic opioid use in the same direction as with OD. Additional differentially methylated CpG sites with suggestive associations mapped to genes implicated in metabolism (OSBPL9), transcriptional regulation (EHMT2), and protein binding and axon guidance (TUBA1C).

When we examined methylation patterns of these GWS CpG sites in relation to genotype, we determined that the methylation state of cg17426237 (PARG) was associated with rs2611513, which maps to PRKG1. Rs2611513 was nominally significantly associated to OD (β = 0.17, p = 0.02) in EAs in our published GWAS12; the OD risk allele is associated with decreased methylation at this CpG site. This shows the same effect direction as in the current EWAS analysis, where OD subjects show decreased methylation at this CpG site, and the risk variant predicted decreased methylation. These findings suggest that risk variants could reflect epigenetic regulatory loops, modulating gene expression by an epigenetic mechanism.

When examining the estimated methylation age in the peripheral blood, no differences were observed between opioid-exposed controls and OD subjects. In a previous study conducted in human postmortem striatal tissue, neurons of heroin abusers exhibited a younger epigenetic age than control subjects38. The differences observed could be due to cell type specificity in DNA methylation age associated with opioid use. Another possibility is differences in the sample composition between the studies; for example, control subjects for whom exposure to opioids were not required, compared to the current study, in which all controls were opioid-exposed. However, larger samples are needed to investigate this further.

This study has several strengths. It is the largest EWAS sample to date for the study of OD. Important confounding variables were considered in the EWAS analysis, such as smoking status, population stratification, and cell type composition. The sample size is moderate, but power was increased by using a carefully ascertained sample of a single ancestry and sex for both cases and opioid-exposed controls. Further, we integrated genetic and epigenetic information to investigate the interplay between genetic and environmental mechanisms in OD.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Identifying a validation data set was not possible at this point because this is, to our knowledge, the first EWAS study of OD. Thus, future studies are needed to examine whether the GWS CpG sites identified can be replicated in an independent sample, in males, or in other populations. Another limitation is the use of peripheral tissue to investigate DNA methylation differences associated with OD. We used different publicly available datasets to conduct a cross-tissue proxy of the methylation and gene expression patterns of the genes identified. Further, the purpose of this study was to identify potential peripheral biomarkers of OD that could inform prognosis and potential treatments in humans. Although brain is a tissue of greater interest, it is inaccessible in living subjects.

Given the cross-sectional design of the study, we were unable to determine whether the changes in DNA methylation caused or were a consequence of OD. Future longitudinal studies are needed to investigate this further. Larger samples will allow for better power to investigate the effect of additional confounding factors such as polydrug use (present in 74% of the sample; 95.7% in OD cases and 36.3% in opioid-exposed controls) or comorbidity with psychiatric diagnoses. Improved power will also likely facilitate the identification of additional novel loci. Despite these limitations, this is the first study of its kind to identify DNA methylation signatures associated with OD. Based on our sensitivity analysis in our top signals, the association between the GWS CpG sites identified and OD goes beyond the influence of comorbidity with other drug dependencies (i.e., AD and CoCD). These data suggest that hypomethylation at these loci may, if replicated, be used as specific biomarkers for OD.

Conclusions

This study is the first genome-wide DNA methylation association study of OD in women. After correction for multiple testing, we identified three GWS DNA methylation sites in genes involved in chromatin remodeling, DNA binding, and cell processes. Further, genetic variants in one of these genes have previously been identified in GWASs of psychiatric disorders.

Change history

05 December 2019

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Compton, W. M. & Volkow, N. D. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2, 103–107 (2006).

Florence, C. S., Zhou, C., Luo, F. & Xu, L. The Economic Burden of Prescription Opioid Overdose, Abuse, and Dependence in the United States, 2013. Medical care. 10, 901–906 (2016).

Compton, W. M. & Volkow, N. D. Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug and alcohol dependence. S4–7 (2006).

Paulozzi, L. J. Opioid analgesic involvement in drug abuse deaths in American metropolitan areas. American journal of public health. 10, 1755–1757 (2006).

Paulozzi, L. J., Budnitz, D. S. & Xi, Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 9, 618–627 (2006).

Paulozzi, L. J. & Xi, Y. Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban-rural status and by drug type. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 10, 997–1005 (2008).

Mercado, M. C. et al. Increase in Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Fentanyl-Rhode Island, January 2012-March 2014. Pain medicine. 3, 511–523 (2018).

Okie, S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. The New England journal of medicine. 21, 1981–1985 (2010).

Volkow, N. D., Frieden, T. R., Hyde, P. S. & Cha, S. S. Medication-assisted therapies–tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. The New England journal of medicine. 22, 2063–2066 (2014).

Gelernter, J. Genetics of complex traits in psychiatry. Biological psychiatry. 1, 36–42 (2015).

Gelernter, J. et al. Genome-wide association study of opioid dependence: multiple associations mapped to calcium and potassium pathways. Biological psychiatry. 1, 66–74 (2014).

Cheng, Z. et al. Genome-wide Association Study Identifies a Regulatory Variant of RGMA Associated With Opioid Dependence in European Americans. Biological psychiatry (2018).

Chorbov, V. M., Todorov, A. A., Lynskey, M. T. & Cicero, T. J. Elevated levels of DNA methylation at the OPRM1 promoter in blood and sperm from male opioid addicts. Journal of opioid management. 4, 258–264 (2011).

Nielsen, D. A. et al. Increased OPRM1 DNA methylation in lymphocytes of methadone-maintained former heroin addicts. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 4, 867–873 (2009).

Nielsen, D. A. et al. Ethnic diversity of DNA methylation in the OPRM1 promoter region in lymphocytes of heroin addicts. Human genetics. 6, 639–649 (2010).

Ebrahimi, G. et al. Elevated levels of DNA methylation at the OPRM1 promoter region in men with opioid use disorder. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse 1–7 (2017).

Oertel, B. G. et al. Genetic-epigenetic interaction modulates mu-opioid receptor regulation. Human molecular genetics. 21, 4751–4760 (2012).

Zhang, H. et al. Hypermethylation of OPRM1 promoter region in European Americans with alcohol dependence. Journal of human genetics. 10, 670–675 (2012).

Knothe, C. et al. Pharmacoepigenetics of the role of DNA methylation in mu-opioid receptor expression in different human brain regions. Epigenomics. 12, 1583–1599 (2016).

Marie-Claire, C. et al. Variability of response to methadone: genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in two independent cohorts. Epigenomics. 2, 181–195 (2016).

Gelernter, J. et al. Genome-wide association study of cocaine dependence and related traits: FAM53B identified as a risk gene. Molecular psychiatry. 6, 717–723 (2014).

Gelernter, J. et al. Genome-wide association study of nicotine dependence in American populations: identification of novel risk loci in both African-Americans and European-Americans. Biological psychiatry. 5, 493–503 (2015).

Gelernter, J. et al. Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence:significant findings in African- and European-Americans including novel risk loci. Molecular psychiatry. 1, 41–49 (2014).

Aryee, M. J. et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 10, 1363–1369 (2014).

Leek, J. T., Johnson, W. E., Parker, H. S., Jaffe, A. E. & Storey, J. D. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 6, 882–883 (2012).

Fortin, J. P. et al. Functional normalization of 450 k methylation array data improves replication in large cancer studies. Genome biology. 12, 503 (2014).

Jaffe, A. E. & Irizarry, R. A. Accounting for cellular heterogeneity is critical in epigenome-wide association studies. Genome biology. 2, R31 (2014).

Houseman, E. A. et al. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC bioinformatics 86 (2012).

Barfield, R. T. et al. Accounting for population stratification in DNA methylation studies. Genet Epidemiol. 3, 231–241 (2014).

Barfield, R. T., Kilaru, V., Smith, A. K. & Conneely, K. N. CpGassoc: an R function for analysis of DNA methylation microarray data. Bioinformatics. 9, 1280–1281 (2012).

Joehanes, R. et al. Epigenetic Signatures of Cigarette Smoking. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 5, 436–447 (2016).

Chang, C. C. et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 7 (2015).

Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 9875, 1371–1379 (2013).

Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study C. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nature genetics. 10, 969–976 (2011).

Li, Z. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 30 new susceptibility loci for schizophrenia. Nature genetics. 11, 1576–1583 (2017).

Okbay, A. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature. 7604, 539–542 (2016).

Hein, M. Y. et al. A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell. 3, 712–723 (2015).

Kozlenkov, A. et al. DNA Methylation Profiling of Human Prefrontal Cortex Neurons in Heroin Users Shows Significant Difference between Genomic Contexts of Hyper- and Hypomethylation and a Younger Epigenetic Age. Genes. 6 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the recruitment and assessment efforts provided at Yale University School of Medicine and the APT Foundation by James Poling, Ph.D.; at McLean Hospital by Roger Weiss, M.D., at the Medical University of South Carolina by Kathleen Brady, M.D., Ph.D., and Raymond Anton, M.D.; and at the University of Pennsylvania by David Oslin, M.D. We are grateful to Ann Marie Lacobelle and Christa Robinson for their excellent technical assistance, to the SSADDA interviewers who devoted substantial time and effort to phenotype the study sample, and to John Farrell and Alexan Mardigan for database management assistance. Assistance with data cleaning was provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DA12690, R01 AA11330, 5T32 MH14276, and P50 AA12870; the Biological Sciences Training Program through Grant Number 5T32 MH14276 and the NARSAD Young Investigator Grant to JLMO. Funding support for genotyping, which was performed at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Inherited Disease Research, was provided by the NIH GEI (U01HG004438), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the NIH contract “High throughput genotyping for studying the genetic contributions to human disease” (HHSN268200782096C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design, data acquisition, or data analysis and interpretation. Specifically, J.L.M.O contributed to the study design as well as data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. Z.C. performed data analysis, and interpretation. H.Z. performed data interpretation. H.R.K. performed data acquisition and interpretation. J.G. contributed to the study design as well as data acquisition and interpretation. J.L.M.O. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and were involved in revising the manuscript and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

Dr. Kranzler has been an advisory board member, consultant, or CME speaker for Alkermes, Indivior and Lundbeck. He is also a member of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology’s Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative, which was supported in the last three years by AbbVie, Alkermes, Ethypharm, Indivior, Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Arbor, and Amygdala Neurosciences. Drs Kranzler and Gelernter are named as inventors on PCT patent application #15/878,640 entitled: “Genotype-guided dosing of opioid agonists,” filed January 24, 2018. Drs Montalvo-Ortiz, Cheng and Zhang reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Montalvo-Ortiz, J.L., Cheng, Z., Kranzler, H.R. et al. Genomewide Study of Epigenetic Biomarkers of Opioid Dependence in European- American Women. Sci Rep 9, 4660 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41110-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41110-7

This article is cited by

-

Native doublet microtubules from Tetrahymena thermophila reveal the importance of outer junction proteins

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Profiling neuronal methylome and hydroxymethylome of opioid use disorder in the human orbitofrontal cortex

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Genetics of substance use disorders in the era of big data

Nature Reviews Genetics (2021)

-

Effect of short-term prescription opioids on DNA methylation of the OPRM1 promoter

Clinical Epigenetics (2020)

-

Genetic variation regulates opioid-induced respiratory depression in mice

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.