Abstract

Cardiovascular risk rapidly increased following exposure to air pollution. Changes in human autonomic regulation have been implicated based on epidemiological associations between exposure estimates and indirect autonomic nervous system measurements. We conducted a mechanistic study to test the hypothesis that, in healthy older individuals, well-defined experimental exposure to ultrafine carbon particles (UFP) increases sympathetic nervous system activity and more so with added ozone (O3). Eighteen participants (age >50 years, 6 women) were exposed to filtered air (Air), UFP, and UFP + O3 combination for 3 hours during intermittent bicycle ergometer training in a randomized, crossover, double-blind fashion. Two hours following exposure, respiration, electrocardiogram, blood pressure, and muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) were recorded at supine rest, during deep breathing, and during a Valsalva manoeuvre. Catechols and inflammatory marker levels were measured in venous blood samples. Induced sputum was obtained 3.5 h after exposure. Combined exposure to UFP + O3 but not UFP alone, caused a significant increase in sputum neutrophils and circulating leucocytes. Norepinephrine was modestly increased while the ratio between plasma dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG) and norepinephrine levels, a marker for norepinephrine clearance, was reduced with UFP + O3. Resting MSNA was not different (47 ± 12 with Air, 47 ± 14 with UFP, and 45 ± 14 bursts/min with UFP + O3). Indices of parasympathetic heart rate control were unaffected by experimental air pollution. Our study suggests that combined exposure to modest UFP and O3 levels increases peripheral norepinephrine availability through decreased clearance rather than changes in central autonomic activity. Pulmonary inflammatory response may have perturbed pulmonary endothelial norepinephrine clearance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization estimated that air pollution is the 13th leading cause of mortality worldwide1. A large proportion of the excess mortality can be attributed to cardiovascular causes2. The risk for acute myocardial infarction was increased two and 24 hours following increased fine particle exposure3. Ventricular arrhythmias were also more likely when patients were subject to short-term exposure to fine particles4. During an air pollution episode, average resting heart rate and blood pressure were modestly increased. The odds ratio of having hypertensive blood pressure readings was 1.635,6. The rapid increase in blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiovascular risk suggests autonomic nervous system involvement with augmented adrenergic drive and parasympathetic withdrawal. Indeed, for each 1 mg/m3 increment in workplace exposure to fine particles with ≤2.5 µm mean aerodynamic diameter (PM2.5), heart rate variability in 24-hour electrocardiograms decreased 2.66%7. Heart rate variability decreased within two hours8 and remained suppressed the following day9. Experimental exposure to mixed coarse and fine particles elicited similar responses10. Fine particle exposure was also pressor in rats11,12. On the other hand, an air-filtering device was reported to attenuate plasma norepinephrine concentrations in humans13. Older persons may be more susceptible to air pollution because of detrimental effects on autonomic cardiovascular control as opposed to young subjects14. Indeed, particulate matter and O3 have been shown to decrease heart rate variability in this population15. Greater susceptibility may also arise from the ability of nanoparticles to cause localized accumulations after translocation from airways and lungs into the brain via neuronal and circulatory pathways16. Furthermore, the adverse effects of air pollution may have greater impact on the health status in the elderly17. Ultrafine particles with ≤0.1 µm aerodynamic diameter appear to be particularly harmful because they escape broncho-mucociliary clearance and reach alveoli18. Epidemiological studies showed associations between ultrafine carbon particle exposure and cardiopulmonary morbidity and mortality which may operate as a universal carrier for various chemicals19. Ozone (O3) is another pollutant contributing to adverse cardiovascular effects20,21,22. Airway inflammation is augmented with concomitant exposure to carbon particles and O323.

So far, much of the evidence linking air pollutant exposure with changes in human cardiovascular autonomic regulation relied on epidemiological studies, exposure estimates, and indirect autonomic nervous system measurements. Moreover, mechanism-oriented studies are rarely conducted in older persons who are more susceptible to air pollution. Therefore, we conducted a study in healthy individuals >50 years, to test the hypotheses that short-term experimental exposure to UFP changes the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic cardiovascular control towards sympathetic predominance. We reasoned that combined exposure to particles and O3 would have an even greater effect. Our findings suggest that short-term experimental air pollution augments peripheral norepinephrine availability through changes in peripheral norepinephrine clearance rather than increased efferent sympathetic nerve traffic.

Methods

Subjects

We screened 57 healthy subjects >50 years of age. Eight postmenopausal women and 17 men met all inclusion and exclusion criteria and entered the study between September 2013 and June 2015. Smokers and individuals with clinically apparent cardiovascular and/or pulmonary diseases were excluded. Specifically, we excluded patients with asthma of any severity while atopy or atopic rhinitis was not an exclusion criterion. We included 1 subject with asymptomatic atopy and 2 subjects with mild or sporadic rhinitis symptoms during their respective pollen season. Both had their visits outside of their respective season. We also excluded individuals on medications strongly affecting autonomic nervous system function, e. g. norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, whereas stable medication with slight to moderate autonomic effects was tolerated. We did not select subjects with regard to their domestic or workplace air pollution.

Twenty participants (6 women and 14 men) completed all three study visits with successful microneurography recordings. Two participants had lost substantial amounts of body weight during the study even though we had advised all participants not to change their exercise and dietary habits. Because both had begun an intense lifestyle intervention including regular physical training, they were excluded before the study was unblinded leaving 18 participants in the primary analysis set. The CONSORT diagram for the trial is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Characteristics of the study population are given in Table 1.

Study Design and Protocol

The ethics committee of Hannover Medical School approved our study and all participants gave written informed consent before enrolment. The methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (registration number: NCT01914783, posted: 2013-08-02). In this randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind, three-period, three-sequence crossover study participants were exposed to Air (placebo), UFP, and the combination UFP + O3. Washout periods between exposures were at least eight weeks. Data were collected at the Fraunhofer Institute for Toxicology and Experimental Medicine (Hannover ITEM) and at the Clinical Research Centre of Hannover Medical School.

Exposure

We exposed subjects to Air, UFP, or UFP + O3, in a dedicated exposure chamber equipped with a bicycle ergometer. UFP (50 μg/m³) and O3 (250 ppb) generation are described in Supplementary Methods24,25. Detailed justification for UFP and O3 dosage is given in Supplementary Methods. In brief, the O3 concentration used in our study exceeds the 1 hour alarm level in Germany about 2 fold; the UFP exposure is in the range of current PM10 and PM2.5 threshold levels.

At experimental visits, participants were continuously exposed for 3 h (Supplementary Fig. S2). During the exposure period subjects underwent alternating 15-min cycles of rest and exercise at previously determined workload (Supplementary Methods). The approach has been used in numerous challenge studies worldwide and guarantees a sufficient inflammatory response26. We monitored ECG and oxygen saturation continuously and measured brachial blood pressure twice at the end of each cycle. Following exposure, subjects ingested a standardized light lunch. Then, they were instrumented for cardiovascular and autonomic measurements which started approximately 1.5 h after the exposure. Finally, ~3.5 h after the end of the exposure, participants were subjected to sputum induction (Supplementary Methods) before they went home. The inflammatory response after a 3-h exposure to 250 ppb O3 can already be detected 1 h after exposure and lasts at least for 24 h. The chosen time window for autonomic, cardiovascular, and sputum measurements corresponds to the inflammatory response27.

Measurements

Subjects were instrumented in the supine position in a quiet laboratory at an ambient temperature of 22–23 °C. We inserted an antecubital venous catheter and continuously recorded respiration, ECG, thoracic impedance (Cardioscreen, Medis GmbH, Ilmenau, Germany), and beat-by-beat finger blood pressure (Finometer, FMS, Arnhem, The Netherlands). We also measured brachial blood pressure with an automated oscillometric device (Dinamap, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and cardiac output by inert gas rebreathing (Innocor, Innovision, Odense, Denmark). We recorded postganglionic, multiunit muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) from within the peroneal nerve. After achieving stable resting baseline, respiration, blood pressure, heart rate, and MSNA were recorded for 10 minutes followed by cardiac output measurements and venous sampling for catecholamine, renin, and dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG) determination (Supplementary Methods)28,29,30. Then, subjects underwent controlled slow breathing (6 breaths per minute) and a Valsalva manoeuvre for hemodynamic and autonomic assessment. Thereafter, we obtained venous blood samples for inflammatory marker quantification. Finally, we used procedures for sputum induction and flow cytometry of sputum cells as described previously31. We obtained estimates of heart rate and systolic blood pressure variability from 5-min supine rest recordings. Spontaneous cardiac baroreflex sensitivity was calculated as the slope of the linear regression between instantaneous systolic blood pressure and subsequent R-R intervals using the sequence method32 or by cross-spectral transfer function analysis in the low-frequency range between 0.05 and 0.15 Hz (Supplementary Methods).

Statistics

We planned the study to test the following hypotheses: In healthy older subjects, experimental exposure to carbon black UFP increases sympathetic nervous system activity compared with filtered Air sham exposure (primary hypothesis). Moreover, combined UFP + O3 exposure increases sympathetic nervous system activity more than UFP exposure alone (secondary hypothesis). The primary endpoint of the study was 5-min resting MSNA burst frequency [bursts/min]. Secondary endpoints were resting MSNA burst incidence [bursts/100 heart beats], which corrects MSNA for heart rate, and total MSNA [arbitrary units], which takes into account burst strength. We also explored arterial blood pressure, heart rate, cardiac output, blood pressure and heart rate variability, baroreflex sensitivity, plasma norepinephrine, DHPG, and renin concentrations, and inflammation parameters.

Analysis of the primary endpoint was performed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model that allows for the adjustment for period effects according to the Hills-Armitage approach using a fixed effects model (Supplementary Methods)33. A closed testing procedure was used to preserve a two-sided type-I error of 0.05: The overall test in the ANOVA had to have a P value < 0.05 to proceed to pairwise comparisons between exposure groups. All remaining parameters were analysed by repeated measures ANOVA without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Exposure information is expressed as median ± interquartile range (IQR); physiologic data are expressed as mean ± SD. For primary endpoint contrasts confidence intervals [CI] are also provided.

Results

Experimental exposure to UFP and O3

During exposure with Air, UFP, and UFP + O3 particle mass concentrations were 19.9 ± 10.2, 68.5 ± 13.7, and 69.1 ± 19.8 µg/m³, respectively. UFP diameters were 50.6 ± 1.9 (UFP alone) and 47.5 ± 3.6 nm (UFP + O3) with a mean geometric standard deviation in particle size of 1.7 nm. The median O3 concentration during UFP + O3 exposure was 249.5 ± 3.7 ppb. Median relative humidity was 42.1 ± 11.6, 36.3 ± 10.4, and 41.5 ± 11.1% with median temperatures of 22.6 ± 0.3, 22.7 ± 0.2, and 22.6 ± 0.2 °C during exposure to Air, UFP, and UFP + O3, respectively.

Combined exposure to UFP + O3 elicits local pulmonary inflammation affecting pulmonary function

UFP exposure alone did not significantly change inflammatory markers. In contrast, the percentage of neutrophils in induced sputum (P < 0.001), serum club cell protein (CC16) levels (P < 0.001), and blood leukocytes (P < 0.001) were significantly increased following combined UFP + O3 exposure (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). Serum myeloperoxidase, malondialdehyde, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein did not change. Localized pulmonary inflammation with UFP + O3 was associated with modest impairments in lung function (Supplementary Table S1). Over 3 h of intermittent exercise in Air we observed increases in forced vital capacity (ΔFVC: 191 ± 180 ml, P < 0.001) and forced expiratory volume in one second (ΔFEV1: 102 ± 89 ml, P < 0.001). Such increases were lacking with combined UFP + O3 exposure (ΔFVC: 8 ± 343 ml, P = 0.918; ΔFEV1: −57 ± 210 ml, P = 0.262). During the microneurographic measurements approximately 2 h after combined UFP + O3 exposure, respiratory rate tended to be slightly elevated (P = 0.085, Table 2). These findings are in line with the idea that acute O3–induced lung function changes are dominated by involuntary inhibition of inspiration34. Lung function was unchanged with UFP exposure alone suggesting that both pollutants may interact in terms of pulmonary inflammation and that inflammation is required to acutely perturb pulmonary function. Nevertheless, exposures were well tolerated and we did not observe clinically relevant changes in lung function, reduced oxygen saturation, or serious adverse events.

Inflammatory markers (n = 18). The plots show individual differences of inflammatory markers with ultrafine particles or ultrafine particles + ozone compared with filtered air. Only combined ultrafine particles + ozone exposure caused an increase in these markers. Serum malondialdehyde and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein did not change with exposure and have been omitted. Upper panel: Neutrophils in sputum that has been obtained ~3.5 h after the end of exposure. Lower panels: Club cell protein levels (CC16) and leukocytes in blood samples that have been obtained ~2.5 h after the end of exposure.

Evidence for increased systemic norepinephrine availability

We conducted a detailed biochemical catechol analysis to gauge influences of experimental air pollution on peripheral catecholamine availability and metabolism. UFP alone did not elicit changes in venous plasma epinephrine or norepinephrine concentrations. However, following UFP + O3, we observed a significant increase in plasma norepinephrine concentrations (P = 0.020, Table 3) while plasma epinephrine did not change (P = 0.254). The half-life of catecholamines in plasma is less than 2 mins. Therefore, increased norepinephrine levels more than 1.5 h after the exposure cannot be explained by sympathetic activation during exposure. Much of the released norepinephrine is taken up through the neuronal norepinephrine transporter (uptake 1) and subsequently metabolized via monoamine oxidases to dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG). Therefore, plasma DHPG and the DHPG to norepinephrine ratio can be utilized to assess norepinephrine clearance mechanisms. Following UFP + O3, we observed a reduction in the DHPG to norepinephrine ratio (P = 0.016, Table 3, Fig. 2). The finding suggests that the increase in venous plasma norepinephrine following UFP + O3 is caused at least in part by reduced peripheral norepinephrine uptake and metabolism.

Catechols (n = 18). The plots show individual differences of catechols with ultrafine particles (UFP) or UFP + ozone (O3) compared with filtered air. Assuming the null hypothesis, the mean of the data points would fall on the zero line (dashed line). Combined exposure to UFP + O3 tended to increase norepinephrine plasma levels (NE, upper panel). The ratio between dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG, middle panel) and NE may serve as biochemical indicator for norepinephrine reuptake (lower panel). Its decrease could explain the increase in plasma NE.

Changes in norepinephrine availability are not explained by altered central autonomic nervous system regulation

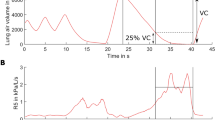

Muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) measurements through microneurography are considered the Gold standard to assess vasoconstrictor sympathetic nerve traffic in human beings. Figure 3 illustrates representative MSNA recordings during the three-sequence crossover study for three subjects with different exposure sequences. MSNA and neurohumoral data are presented in Table 3, Fig. 2, and in Supplementary Table S2. We did not observe clinically relevant differences in MSNA burst frequency between exposures. The overall test yielded a P value of 0.633, and all pairwise comparisons expressed in bursts/min were UFP + O3 minus UFP: −2.3, 95% CI [−8.5, 3.9], P = 0.458; Air minus UFP: 0.5, 95% CI [−5.8, 6.7], P = 0.883; UFP + O3 minus Air: −2.8, 95% CI [−9.0, 3.5], P = 0.376. Moreover, also MSNA burst incidence and MSNA total activity did not differ between exposures. Overall, these observations exclude a major change in centrally generated sympathetic activity with experimental air pollution. The conclusion is supported by the observation that plasma renin concentrations, which respond to changes in renal sympathetic drive, did not increase with experimental air pollution (22.5 ± 42.1, 16.5 ± 21.8, and 15.3 ± 12.0 ng/l following exposure to Air, UFP, and UFP + O3, respectively P = 0.425).

Next, we computed indirect measures for autonomic cardiovascular control that respond to changes in central nervous sympathetic or parasympathetic control (Table 3). Systolic blood pressure variabilities were comparable following exposure to Air, UFP, or UFP + O3. RR interval variability and cardiac baroreflex gain, which are related to cardiac vagal activity, did not differ between interventions. Likewise, maximum sympathetic response during Valsalva phase IIb was similar as was respiratory sinus arrhythmia with deep breathing and Valsalva ratio as indices of parasympathetic heart rate control. Thus, modest experimental air pollution while producing pulmonary inflammation and changes in lung function is not sufficient to perturb central sympathetic or parasympathetic cardiovascular control mechanisms. Since sympathetic nerve traffic and the relation between norepinephrine and MSNA were unchanged, the increase in norepinephrine with UFP + O3 cannot be explained by augmented centrally generated sympathetic outflow.

Altered norepinephrine availability does not translate into changes in hemodynamic measurements

Resting hemodynamic and respiration data obtained during microneurography measurements are provided in Table 2. Hemodynamics were similar between study days. We reasoned that influences of experimental air pollution on hemodynamics could be unmasked during states of raised sympathetic activity. Therefore, we also assessed hemodynamic responses during exercise in the exposure chamber (see Supplementary Fig. S3 for individual data). Heart rate and systolic blood pressure increased similarly with exercise on the three study days (Air: 41.9 ± 11.4, UFP: 37.2 ± 14.3, UFP + O3: 38.1 ± 15.8 bpm, P = 0.350; Air: 29.5 ± 12.9, UFP: 26.7 ± 11.6, UFP + O3: 27.0 ± 13.9 mm Hg, P = 0.488). Diastolic blood pressure increased less with UFP vs. UFP + O3 (Air: 2.7 ± 7.5, UFP: 0.4 ± 4.7, UFP + O3: 4.5 ± 6.9 mm Hg, P = 0.028). Resting hemodynamics between the 15-min exercise bouts were similar during all exposures (Table 2). Thus, in otherwise healthy older persons, experimental air pollution while eliciting pulmonary inflammation and reduced norepinephrine turnover does not produce major changes in blood pressure and heart rate control at rest or during physical exercise.

Discussion

Our study is the first examining the effects of rigorously controlled short-term experimental exposure to UFP with and without O3 on directly measured sympathetic activity. The main finding is that the exposure did not elicit clinically relevant changes in sympathetic activity at rest or during sympathetic stimulation. However, we observed an about 13% increase in venous norepinephrine concentrations with reduction in the DHPG to norepinephrine ratio following combined UFP + O3 exposure. By comparison, smoking 20 cigarettes per day over one week increased plasma norepinephrine approximately 10% compared with air inhalation35. Our study suggests diminished catecholamine clearance, a hitherto unknown mechanism through which environmental pollutants may perturb human adrenergic responses. In healthy subjects small amounts of pressor compounds do not translate into blood pressure increases as they are effectively balanced by counterregulatory responses, such as baroreflexes. In diseased subjects with elevated sympathetic activity and diminished baroreflex function, however, reduced norepinephrine reuptake may have detrimental effects.

Highly controlled exposure to environmental pollutants in a rigorously designed double-blind and crossover fashion is a particular strength of our study. Measured exposures to UFP and O3 were rather stable with little deviation from planned experimental conditions. We applied UFP and O3 concentrations that are known to elicit biological responses in human subjects. Carbon UFP inhalation in concentrations applied in our study transiently activated platelets in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus36. Unlike UFP exposure, which is known to have a limited effect on human airway inflammation, addition of O3 elicited a robust inflammatory response. In fact, sputum neutrophil counts and circulating inflammatory markers increased sharply. In induced sputum, the magnitude of the inflammatory response to combined UFP + O3 exposure was similar to studies applying O3 only37. Bronchial biopsies taken following acute O3 exposure in healthy subjects showed increased percentage of neutrophils and total protein concentration38,39.

Combining microneurography with hemodynamic measurements, plasma catecholamine determination, and heart rate as well as blood pressure variability analysis provided comprehensive insight in cardiovascular autonomic responses to experimental air pollution. It has been speculated that environmental pollutants may engage afferent neural pathways in the lung or elsewhere in the body, thereby changing autonomic balance towards sympathetic predominance. In fact, O3 responsive bronchial C fibres have been demonstrated in anesthetized and artificially ventilated dogs40. Due to their size, UFP may pass the alveolo-capillary barrier41 and enter the brain42 where they could directly affect autonomic circuits. Yet, we did not observe clinically relevant changes in MSNA at rest, during deep breathing, or during baroreflex-mediated sympathetic activation elicited by the Valsalva manoeuvre. Blood pressure and heart rate did not respond either. Furthermore, blood pressure and heart rate recordings during exposure did not differ between interventions. Our findings challenge the idea that UFP with or without O3 elicit substantial changes in centrally generated sympathetic activity or parasympathetic heart rate control.

The plasma norepinephrine increase following UFP + O3 exposure cannot be explained by increased central sympathetic drive because MSNA did not change. Dissociation between circulating norepinephrine and MSNA could result from altered coupling between electrical nerve activity and transmitter release or changed norepinephrine uptake/metabolism. Approximately 80–90% of the released norepinephrine is taken up again by the norepinephrine transporter and either repackaged or enzymatically degraded by monoamine oxidases to DHPG. Therefore, the DHPG to norepinephrine ratio has been proven useful as biochemical marker for neural norepinephrine uptake and metabolism43. Indeed, genetic norepinephrine transporter deficiency44 and pharmacological norepinephrine transporter inhibition45,46,47 feature reductions in the ratio between plasma DHPG and norepinephrine. The observation that the ratio was reduced following exposure to UFP + O3 is consistent with reduction in norepinephrine uptake and metabolism through this pathway. Besides their expression on adrenergic neurons, norepinephrine transporters are also present on lung endothelial cells48,49, and contribute to catecholamine clearance in newborn lambs, in dogs, and in human subjects50,51,52. We cannot differentiate individual contributions of lung endothelium and adrenergic neurons to the change in the DHPG/norepinephrine ratio. Particulate matter inhalation causes endothelial injury, reflected by circulating endothelial microparticles derived from apoptosis53. We speculate that pulmonary endothelial inflammation could affect endothelial catecholamine clearance through the norepinephrine transporter. If so, reduced clearance could augment catecholamine concentrations entering the coronary circulation, particularly during profound sympathoadrenal activation. We cannot exclude that other local or systemic changes, that are affected by UFP + O3 exposure, contributed to the response. The cellular regulation of the norepinephrine transporter has been studied in great detail54. For example, protein kinase-C, which is targeted by multiple neurotransmitters and hormones, affects norepinephrine transporter trafficking. Yet, whether and how these mechanisms contribute to norepinephrine uptake in human beings is largely unknown.

Limitations

Our study was sufficiently powered to detect clinically relevant changes in MSNA. We cannot exclude subtle changes in cardiovascular autonomic control that may be relevant on the population level. Yet, MSNA was numerically lower following UFP exposures compared to filtered air. Furthermore, environmental fine particles contain minerals, metals, road dust, combustion residues, SO2 and NOX from fires and engine exhaust among others. Particle composition depends on sources, site, season, and weather conditions55. Potential interactions between components of airborne substance mixtures on human health have been poorly investigated56. Observations on carbon UFP cannot be simply extrapolated to environmental UFP exposure. In any event, exposure to particles sampled at different locations produced differential cardiovascular responses in human subjects57. We did not obtain a full dose-response relationship between exposure and cardiovascular autonomic regulation. We used a short-term exposure model whereas typical ambient air pollution periods are of longer duration and often repetitive. Yet, even two-hour exposure may trigger cardiovascular events3,8. Our idea was to assess autonomic function using microneurography and plasma sampling when the inflammatory process is fully developed. However, we cannot rule out that there is inflammation-independent sympathetic excitation that would have been detected only during or shortly after the exposure. Finally, we studied older otherwise healthy individuals and, therefore, cannot exclude more marked responses in patients with established cardiovascular or pulmonary disease.

Conclusions

The epidemiological evidence implicating environmental pollutants in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is compelling. Since a larger proportion of the world population will live in urban environments in the future, the relevance of these mechanisms for cardiovascular health may increase further. Yet, epidemiological studies have their limitations in discerning the contribution of individual pollutants on cardiovascular health and may not suffice to design targeted interventions. The fact that air pollution and environmental noise58, which commonly occur together, are both associated with increased cardiovascular risk is a prime example. Our observations suggest that exposure to well-defined pollutants in a rigorously controlled environment combined with high-fidelity human phenotyping is suitable to confirm or to exclude hypotheses generated in large-scale epidemiological studies and to gain mechanistic insight. While acute UFP exposure with or without O3 did not alter central sympathetic or parasympathetic activity, we observed subtle changes in peripheral catechols with combined exposure to UFP and O3 consistent with impaired norepinephrine uptake and metabolism. We suggest that the pulmonary inflammatory response may have perturbed pulmonary endothelial norepinephrine clearance.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organisation World Health Report: reducing risks and promoting healthy life. (2002).

Pope, C. A. III et al. Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution: epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation 109, 71–77 (2004).

Peters, A., Dockery, D. W., Muller, J. E. & Mittleman, M. A. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation 103, 2810–2815 (2001).

Rich, D. Q. et al. Association of short-term ambient air pollution concentrations and ventricular arrhythmias. Am. J. Epidemiol. 161, 1123–1132 (2005).

Peters, A. et al. Increases in heart rate during an air pollution episode. Am. J. Epidemiol. 150, 1094–1098 (1999).

Ibald-Mulli, A., Stieber, J., Wichmann, H. E., Koenig, W. & Peters, A. Effects of air pollution on blood pressure: a population-based approach. Am. J. Public Health 91, 571–577 (2001).

Magari, S. R. et al. Association of heart rate variability with occupational and environmental exposure to particulate air pollution. Circulation. 104, 986–991 (2001).

Cavallari, J. M. et al. Time course of heart rate variability decline following particulate matter exposures in an occupational cohort. Inhal. Toxicol. 20, 415–422 (2008).

Luttmann-Gibson, H. et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on heart rate variability in senior adults in Steubenville, Ohio. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 48, 780–788 (2006).

Gong, H. Jr. et al. Altered heart-rate variability in asthmatic and healthy volunteers exposed to concentrated ambient coarse particles. Inhal. Toxicol. 16, 335–343 (2004).

Niwa, Y., Hiura, Y., Sawamura, H. & Iwai, N. Inhalation exposure to carbon black induces inflammatory response in rats. Circ. J. 72, 144–149 (2008).

Sun, Q. et al. Air pollution exposure potentiates hypertension through reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of Rho/ROCK. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1760–1766 (2008).

Li, H. et al. Particulate matter exposure and stress hormone levels: A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial of air purification. Circulation 136, 618–627 (2017).

Devlin, R. B., Ghio, A. J., Kehrl, H., Sanders, G. & Cascio, W. Elderly humans exposed to concentrated air pollution particles have decreased heart rate variability. Eur. Respir. J. Suppl. 40, 76s–80s (2003).

Gold, D. R. et al. Ambient pollution and heart rate variability. Circulation 101, 1267–1273 (2000).

Oberdorster, G. et al. Translocation of inhaled ultrafine particles to the brain. Inhal. Toxicol. 16, 437–445 (2004).

Alexeeff, S. E. et al. Ozone exposure, antioxidant genes, and lung function in an elderly cohort: VA normative aging study. Occup. Environ. Med. 65, 736–742 (2008).

Traboulsi, H. et al. Inhaled Pollutants: The molecular scene behind respiratory and systemic diseases associated with ultrafine particulate matter. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (2017).

Janssen, N.A.H. et al. Health effects of black carbon. 86 (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2012).

Chuang, K. J., Chan, C. C., Su, T. C., Lee, C. T. & Tang, C. S. The effect of urban air pollution on inflammation, oxidative stress, coagulation, and autonomic dysfunction in young adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176, 370–376 (2007).

Brook, R. D. et al. Inhalation of fine particulate air pollution and ozone causes acute arterial vasoconstriction in healthy adults. Circulation 105, 1534–1536 (2002).

Bell, M. L., McDermott, A., Zeger, S. L., Samet, J. M. & Dominici, F. Ozone and short-term mortality in 95 US urban communities, 1987-2000. JAMA 292, 2372–2378 (2004).

Jakab, G. J. & Hemenway, D. R. Concomitant exposure to carbon black particulates enhances ozone-induced lung inflammation and suppression of alveolar macrophage phagocytosis. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 41, 221–231 (1994).

Schaumann, F. et al. Effects of ultrafine particles on the allergic inflammation in the lung of asthmatics: results of a double-blinded randomized cross-over clinical pilot study. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 11, 39 (2014).

Lippmann, M. Health effects of ozone. A critical review. JAPCA 39, 672–695 (1989).

Mudway, I. S. & Kelly, F. J. An investigation of inhaled ozone dose and the magnitude of airway inflammation in healthy adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169, 1089–1095 (2004).

Holz, O. et al. Ozone-induced airway inflammatory changes differ between individuals and are reproducible. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159, 776–784 (1999).

Willemsen, J. J., Sweep, C. G., Lenders, J. W. & Ross, H. A. Stability of plasma free metanephrines during collection and storage as assessed by an optimized HPLC method with electrochemical detection. Clin. Chem. 49, 1951–1953 (2003).

Danser, A. H. et al. Determinants of interindividual variation of renin and prorenin concentrations: evidence for a sexual dimorphism of (pro)renin levels in humans. J. Hypertens. 16, 853–862 (1998).

Zoerner, A. A. et al. Unique pentafluorobenzylation and collision-induced dissociation for specific and accurate GC-MS/MS quantification of the catecholamine metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG) in human urine. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 879, 1444–1456 (2011).

Holz, O. et al. Efficacy and safety of inhaled calcium lactate PUR118 in the ozone challenge model–a clinical trial. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 16, 21 (2015).

Bertinieri, G. et al. A new approach to analysis of the arterial baroreflex. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 3(Suppl), 79–81 (1985).

Hills, M. & Armitage, P. The two-period cross-over clinical trial. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 8, 7–20 (1979).

Bromberg, P. A. Mechanisms of the acute effects of inhaled ozone in humans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860, 2771–2781 (2016).

Zevin, S., Saunders, S., Gourlay, S. G., Jacob, P. & Benowitz, N. L. Cardiovascular effects of carbon monoxide and cigarette smoking. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 38, 1633–1638 (2001).

Stewart, J. C. et al. Vascular effects of ultrafine particles in persons with type 2 diabetes. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1692–1698 (2010).

Tank, J. et al. Effect of acute ozone induced airway inflammation on human sympathetic nerve traffic: a randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. PLoS One 6, e18737 (2011).

Stenfors, N. et al. Effect of ozone on bronchial mucosal inflammation in asthmatic and healthy subjects. Respir. Med. 96, 352–358 (2002).

Aris, R. M. et al. Ozone-induced airway inflammation in human subjects as determined by airway lavage and biopsy. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 148, 1363–1372 (1993).

Coleridge, J. C., Coleridge, H. M., Schelegle, E. S. & Green, J. F. Acute inhalation of ozone stimulates bronchial C-fibers and rapidly adapting receptors in dogs. J. Appl. Physiol. 74, 2345–2352 (1993).

Kreyling, W. G., Semmler, M. & Moller, W. Dosimetry and toxicology of ultrafine particles. J. Aerosol. Med. 17, 140–152 (2004).

Semmler, M. et al. Long-term clearance kinetics of inhaled ultrafine insoluble iridium particles from the rat lung, including transient translocation into secondary organs. Inhal. Toxicol. 16, 453–459 (2004).

Vincent, S. et al. Clinical assessment of norepinephrine transporter blockade through biochemical and pharmacological profiles. Circulation 109, 3202–3207 (2004).

Shannon, J. R. et al. Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine transporter deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 541–549 (2000).

Boschmann, M. et al. Norepinephrine transporter function and autonomic control of metabolism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 5130–5137 (2002).

Schroeder, C. et al. Norepinephrine transporter inhibition prevents tilt-induced pre-syncope. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, 516–522 (2006).

Bieck, P. R. et al. Dihydroxyphenylglycol as a Biomarker of Norepinephrine Transporter Inhibition by Atomoxetine: Human Model to Assess Central and Peripheral Effects of Dosing. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 36, 675–683 (2016).

Tseng, Y. T. & Padbury, J. F. Expression of a pulmonary endothelial norepinephrine transporter. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 105, 1187–1191 (1998).

Bryan-Lluka, L. J., Westwood, N. N. & O’Donnell, S. R. Vascular uptake of catecholamines in perfused lungs of the rat occurs by the same process as Uptake1 in noradrenergic neurones. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 345, 319–326 (1992).

Eisenhofer, G. The role of neuronal and extraneuronal plasma membrane transporters in the inactivation of peripheral catecholamines. Pharmacol. Ther. 91, 35–62 (2001).

Eisenhofer, G., Smolich, J. J. & Esler, M. D. Different desipramine-sensitive pulmonary removals of plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine in dogs. Am. J. Physiol. 262, L360–365 (1992).

Smolich, J. J., Cox, H. S. & Esler, M. D. Contribution of lungs to desipramine-induced changes in whole body catecholamine kinetics in newborn lambs. Am. J. Physiol. 276, R243–R250 (1999).

Pope, C. A. III et al. Exposure to fine particulate air pollution is associated with endothelial injury and systemic inflammation. Circ. Res. 119, 1204–1214 (2016).

Kristensen, A. S. et al. SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 585–640 (2011).

Steerenberg, P. A. et al. Relation between sources of particulate air pollution and biological effect parameters in samples from four European cities: an exploratory study. Inhal. Toxicol. 18, 333–346 (2006).

Appleby, P. Fresh air and indoor air quality: Pieces in the sick building puzzle? Facilities 7, 7–11 (1989).

Brook, R. D. et al. Insights into the mechanisms and mediators of the effects of air pollution exposure on blood pressure and vascular function in healthy humans. Hypertension 54, 659–667 (2009).

Recio, A., Linares, C., Banegas, J. R. & Diaz, J. The short-term association of road traffic noise with cardiovascular, respiratory, and diabetes-related mortality. Environ. Res. 150, 383–390 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of our study nurses Ina Groen, Gesine Müller-Schöner, and Katrin Paul. We would like to acknowledge the assistance in DHPG measurement by the Research Core Unit Metabolomics at the Hannover Medical School (Frank M. Gutzki, Volkhard Kaever). We also thank Horst Windt, Wolfgang Bader, Martin Stempfle, and Anja Mitschke for their help. Karsten Heusser and Jens Tank contributed equally to this work. Jens Jordan and Jens M. Hohlfeld contributed equally to this work. The project was supported by a grant to JJ from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG, www.dfg.de, JO 284/10-1). The German Aerospace Center (DLR, www.dlr.de) supported JT, KH, and MM (50WB1117, 50WB1517). AD is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (www.nhlbi.nih.gov, Award Number NIH 2P01HL056693-19).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H., J.T., S.E., J.B., A.K., C.S., N.K., J.J. and J.M.H. conceived and designed the study. O.H. and K.S. performed the experimental exposures and assessed exposure and inflammation data. K.H., J.T. and M.M. did the microneurography. K.H., J.T. and A.D. analysed the hemodynamic and nerve activity recordings. A.H.J.D. and F.C.G.J.S. assessed hormone levels. T.F., A.K., A.G. and K.H. designed and implemented the statistical analyses. K.H., J.T., O.H., K.S., J.J. and J.H. were involved in data interpretation. K.H. prepared figures and tables. K.H., J.T., T.F., A.K., A.G. and J.J. wrote the manuscript text and all authors critically revised and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heusser, K., Tank, J., Holz, O. et al. Ultrafine particles and ozone perturb norepinephrine clearance rather than centrally generated sympathetic activity in humans. Sci Rep 9, 3641 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40343-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40343-w

This article is cited by

-

Short-term exposure to particulate matter on heart rate variability in humans: a systematic review of crossover and controlled studies

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2021)

-

The health effects of ultrafine particles

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.