Abstract

This work investigates the effects of neutron irradiation on nitrogen and hydrogen adsorption in boron-doped activated carbon. Boron-neutron capture generates an energetic lithium nucleus, helium nucleus, and gamma photons, which can alter the surface and structure of pores in activated carbon. The defects introduced by fission tracks are modeled assuming the slit-shaped pores geometry. Sub-critical nitrogen adsorption shows that nitrogen molecules cannot probe the defects created by fission tracks. Hydrogen adsorption isotherms of irradiated samples indicate higher binding energies compared to their non-irradiated parent samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen is currently stored and transported in compressed or liquefied form. Hydrogen storage by chemisorption or physisorption in host materials emerged as an alternative, practical and safe storage technology for the light-duty vehicles. In metal and chemical hydrides, hydrogen is linked to the host through covalent, ionic, or metallic-type bonds. Therefore, chemisorption is hardly reversible and hydrogen is only released at high temperature or upon exposure to a catalyst1,2. In physisorption, hydrogen molecules are adsorbed on the sorbent surface by weak van der Waals forces as a high density fluid3,4,5,6,7,8. In consequence the heat of adsorption of hydrogen is relatively small, resulting in low storage capacities.

Despite tremendous research efforts to develop an efficient hydrogen sorbent, today no ma- terial meets the storage targets set by the US Department of Energy (DOE)9. The most pertinent parameters for development of hydrogen sorbent are gravimetric and volumetric storage capacities of the material. The targets to be reached by 2020, 2025, and in the ultimate limit are respectively set to 0.045, 0.055, and 0.065 kg H2/kg (for gravimetric storage), and 0.030, 0.040, and 0.050 kg H2/L (for volumetric storage). It is important to note that these targets are defined for a complete storage system (counting the mass and volume occupied by the valves, regulators, pipes, materials, and other engineering components), and not for the sorbent material only. The most promising and widely investigated materials for hydrogen storage by physisorption are metal-organic framework (MOFs) and activated carbons (ACs).

ACs are considered as effective hydrogen adsorbents primarily due to their high porosity and large surface areas. Several computational models have defined the optimal pore structure and sur- face chemistry for ACs for hydrogen physisorption10,11,12. Many experimental attempts to improve the surface chemistry and pore size distribution of the existing ACs were reported in the literature. The pore structure were engineered by optimizing the activation process (by selecting an optimal activation temperature and activation agent concentration13,14). Surface chemistry was modified by doping the carbon lattice with boron, aluminum, lithium, calcium and other elements15,16. However, all these attempts led to a marginal improvement of experimentally measured hydrogen storage capacities, in agreement with recent discussion of the theoretical limit of existing AC structure for hydrogen storage17.

In this work, we present a new approach of ACs structure modification by high energetic fission tracks. For that, boron doped ACs were irradiated by neutrons in order to create defects, and modify the pore surface and structure. The effects of neutron irradiation of carbon based materials was first studied by Spalaris et al.18. The authors showed that neutron irradiation of graphite causes a decrease of samples’ surface area. They suggested that upon irradiation the graphite crystallites expend to occupy voids in their immediate vicinity; in consequence the observed sample microporosity decreased. Additional study of boron neutron capture in graphite were reported by Cadenhead and Chung19,20. It has been also shown that the amount of moisture adsorbed in neutron irradiated ACs and silica increased respectively by 18% and 23% (with respect to non- irradiated samples), although only a moderate (<100 m2/g) increase of samples surface area has been observed21,22. Previous attempts of carbon irradiation by neutrons were performed for low surface area carbons. Here we present the first attempt to modify the pore structure of boron- doped high-surface area carbon (3300 m2/g), and report a relevant change in hydrogen adsorption isotherm after neutron irradiation.

Modeling of high-binding-energy sites created by fission tracks

The isotopic abundance of 10B is around 20%. This light element shows a strong tendency to bind with thermal neutrons and form an excited 11B nucleus. This nucleus is unstable, and decays via fission, producing a lithium nucleus, helium nucleus, and gamma photon.

The rate of the reaction R (number of nuclear reactions occurring per second) depends on the boron content of the sample N, the thermal (φth)and epithermal (φepi) fluxes of neutrons, and their cross sections (σth and σepi, respectively) It is given by the following formula:

We used the neutron beam thermal flux ϕth = 8 · 1013 neutrons/cm2 · s, and the epithermal flux ϕepi = 4.8 · 1012 neutrons/cm2.s. The corresponding cross sections are: σth = 3.84 · 10−21 cm2 (for thermal neutrons) and σepi = 1.73 · 10−21 cm2 (for epithermal neutrons). The number of boron atoms (N) in the sample can be estimated using the formula

where m is the sample mass, M is the molar mass of 10B, B is the mass percent of boron in the sample, and η = 0.199 is the isotopic abundance of 10B.

The number of tracks created during sample irradiation is given by

where tirr is the irradiation time in seconds. The factor two in Eq. (3) takes into account the fact that every fission event produces two tracks, one by the emitted alpha particle and the other by the Li nucleus (Fig. 1). The time evolution of 10B amount is described by the equation:

where N0 is the initial number of 10B and N is the number of 10B atoms remaining after the irradiation time tirr. This implies that after 52 minutes of irradiation, 0.1% of 10B atoms would have transformed, and after ~25.4 days of irradiation, half of them would have transformed.

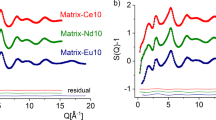

Several techniques allows to study the microporous structure of ACs: gas adsorption, small angle x-ray scattering, high resolution transmission electron microscopy, and others23,24,25,26,27,28. All studies conclude that the structure of ACs consists of randomly oriented curved graphene fragments29,30. The defects created by fission tracks resulting from boron-neutron capture have been modeled assuming the widely used classical slit-shaped pores structure31,32,33,34,35,36. The distance L at which He and Li particles travel in ACs is estimated using the mean distance of helium penetration in carbon based materials37. The number of holes n created by Ntr tracks is approximated to be:

where Ntr is the number of tracks created by He and Li nuclei, D is the average pore width, and r is the distance between graphene pore wall and the first layer of adsorbed H2 which is approximately equal to 3.1 Å38. The carbon-to-carbon pore width (D + 2r) can be estimated from

where Σi (m2/g) is the initial surface area before irradiation, ρapp (g/m3) is the apparent sample density determined from subcritical nitrogen isotherms at 77 K.Substituting Eqs (3) and (6) into (5) leads to:

The surface area created (Σ+) and destroyed (Σ−) by fission tracks of width w are given by the following formulas:

Both surfaces are represented in Fig. 2. The overall change in specific surface area is given by the following equation:

Therefore, to obtain an additional surface area by neutron irradiation of activated carbon (ΔΣ > 0), w must be smaller than 2 · π · r. In addition, the optimal pore width (wopt = π · r) should be 9.3 Å

Experimental

Sample preparation

AC samples were prepared in a multi-step process from corncob consisting of successive chemical activation by phosphoric acid and potassium hydroxide. During the first activation, corn- cob was soaked with phosphoric acid for 12 hours in an oven at 45 °C. The mixture was charred at 480 °C in a nitrogen environment. Charred carbon was then washed with hot water until neu- tralized (pH = 7). The second chemical activation with KOH solution was performed at 790 °C and KOH to carbon ratio of 3:1. The resulting material, after being washed with water (pH = 7) and dried, was then doped by vapor deposition of decaborane. For that, AC and B10H14 were first mixed and degassed for 1 hour at −30 °C under dynamic pumping, then the reaction cell was sealed under vacuum. The sealed cell was heated to 250 °C and maintained at this temperature for 4 hours, to allow B10H14 to sublimate, fill pore space, decompose, and form a sub-monolayer of B10xHz on the pore walls. The sealed cell was then flushed with argon, cooled to 20 °C, transferred under an argon atmosphere to a high-pressure cell and sealed again. Finally, the sample was annealed at 600 °C to decompose the B10H14.

Boron doped samples were neutron irradiated for 1 minute at the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR). Boron content in the boron doped samples is determined by prompt- gamma neutron activation analysis (PGNAA). After irradiation, the samples were etched with hydrogen peroxide to force oxidation in order to create uniform sub-nm pores crisscrossing the pre-fission pore walls. 1 ml of 30% H2O2 and 70% H2O solution was added to the irradiated sample and heated to 750 °C for 1 hour. The sample was then placed in a vacuum oven at 600 °C and annealed for 15 hours. The boron content in the resulting sample is 1.4 wt %. The formation of B-C bonds was confirmed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy in our previous paper12.

Subcritical nitrogen adsorption

Subcritical nitrogen isotherms at 77 K were obtained using an Autosorb-1C (Quantachrome Instruments). Specific surface areas (Σ) are determined from sub-critical nitrogen isotherms using Brunauer-Emett-Teller (BET) theory in the pressure range of 0.01–0.03 P/P0, suitable for analysis of microporous materials. Surface areas larger 1000 m2/g were rounded to the nearest hundred. The total pore volume (Vtot) is measured at a relative pressure of 0.995 P/P0. The porosity (φ), defined as the fraction of sample volume occupied by open pores, is calculated as follow

where ρskel is the skeletal density of the sample, assumed to be 2.0 g/cm3. Typical skeletal densities of amorphous carbons are between 1.8 and 2.1 g/cm3 38.

Quenched solid-density functional theory (QSDFT)35,36 for infinite slit-shaped pores is used to calculate the pore-size distribution. QSDFT is a modified version of the non-local density functional theory (NLDFT). NLDFT which assumes a flat graphitic pore structure, has a significant drawback when applied to nanoporous AC, in which pore walls heterogeneities prevent layering transitions, thus leading to false minimums in the pore-size distribution. This artifact has been completely eliminated in QSDFT that takes into account surface roughness and heterogeneity.

Supercritical hydrogen adsorption

Hydrogen (99.999% purity) adsorption isotherms were measured volumetrically using Hiden HTP-1 volumetric sorption analyzer. Hydrogen gravimetric excess adsorption isotherms were measured at T = 80 K and pressures ranging from 1 to 100 bar. Dry sample mass was determined after annealing the sample at 400 °C and dynamic vacuum (20 torr) for two hours.

Results and Discussion

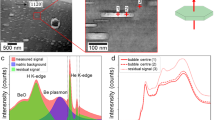

Nitrogen adsorption isotherms, BET surface area, porosity, and pore size distribution showed marginal change upon neutron irradiation. The samples specific surface was 3300 m2/g before, and 3100 m2/g after irradiation. This decrease remains within the estimated experimental 5% error. Similarly, the changes of porosity are small; 0.79 before and 0.78 after irradiation. The pore size distribution does not change upon neutron irradiation (Fig. 3). In both samples the pores width are smaller than 40 Å, with the main peak located at 7.5 Å. This observation is con- sistent with the physical picture of fission. The fission products displace isolated atoms and break bonds between neighboring atoms, but, no matter how energetic they are, they will never remove atoms from the solid or displace them in such a way that would create new regions of high and low carbon density. Such density modulation would be required to create detectable new pores or new surface area, that could be probed by nitrogen molecules. It is worth to recall that the N2 molecules are relatively large, and the width of the tracks and defects created during irradiation is small, approximately equal to 2 · π · r. In consequence, there is no difference between nitrogen adsorption isotherms measured in irradiated and non-irradiated material. Obviously, the mass and skeletal density are also conserved during fission.

Neutron irradiation of samples for 1 minute caused only a small increase in hydrogen storage at room temperature (compared to the non-irradiated sample). On the contrary, Fig. 4 shows that neutron irradiation modified significantly the shape of the isotherm at 80 K. The pressure at which excess adsorption reached its maximum (23 bar) decreases to about half of the value before irradiation (40 bar). The rapid increase in the excess adsorption at lower pressure is indicative of presence of adsorption sites having higher binding energy. The difference in hydrogen adsorption results from the presence of fission tracks (not easily detectable otherwise).

The lattice gas model developed by Aranovich and Donohue was used to determine the bind- ing energy in the irradiated samples39,40. Aranovich and Donohue solved Ono-Kondo equations which relate the density of each adsorbed layer to the bulk gas density and found a general equa- tion for the excess adsorption. Their method was then applied to ACs by Chahine et al.41, and more recently by Gasem et al.42. The gravimetric excess adsorption, determined from solving Ono-Kondo equations for slit shaped pores, depends on four parameters: energy of the hydrogen-hydrogen interaction EH2−H2 (K), energy of hydrogen-carbon interaction E (K), density of the adsorbed film at maximum capacity ρmc (g/ml), and a prefactor C related to the capacity of the adsorbent for a specific gas. If the gas-gas interaction is neglected, one can reduce the number of parameters to three:

where Ge (P, T) is the gravimetric excess adsorption, ρgas(P, T) is the density of hydrogen at pressure P and temperature T, n is the number of layer in a slit pores of the microporous material and w1 is a factor which is a function of coordination number, the hydrogen-hydrogen interaction energy, and other variables discussed in detail by Aranovich and Donohue. For n = 2, the excess adsorption can be written as:

The Ono-Kondo model provides the average binding energy from a single isotherm. Most fre- quently the binding energies are determined from Clausius-Clapeyron equation, using two isotherms at nearby temperatures. This approach is known to be challenging at high coverage because it requires a reliable estimation of the film volume to construct accurate absolute adsorption isotherms3. Using the Ono-Kondo model for supercritical excess adsorption43,44, the average binding energy can be determined by fitting the experimental excess adsorption in Eq. (11) using Levenberg-Marquardt minimization algorithm. The Ono-Kondo fit for the non-irradiated and irradiated sample is presented in Fig. 5. The estimated average binding energies were KJ/mol and 6.6 KJ/mol for the non-irradiated and irradiated samples, respectively. The 6% increase of binding energy after irradiation is consistent with the hypothesis that boron-neutron capture creates fission tracks, in the form of ultra-narrow pores and surface defects, that adsorb hydrogen with high binding energies. In fact, the defects introduced by the fission tracks (edge defects, free radicals, etc…) serve as sites of higher binding for hydrogen and provide higher stor- age capacities at pressures below 42 bar. For instance, at 20 bar the irradiated sample showed an improvement of 9% in storage capacities compared to the non-irradiated sample. This in- crease in hydrogen storage capacities at low pressure is due to the increase of binding energy at low coverage. While the hydrogen storage capacities of the irradiated material are still below the DOE target, this moderate increase in binding energy provides larger hydrogen storage capacities in the low pressure range which is crucial in assessing the tank deliverable metrics for practical low-pressure applications.

Conclusion

We showed that neutron irradiation of boron-doped activated carbons alters the surface and pore structure, introducing defects that act as high energy binding sites for adsorbed hydrogen. It leads to a 6% increase of average binding energies in irradiated samples with respect to their non- irradiated parent samples. In addition, this increase is larger at low coverage, resulting in an increase of 9% in the hydrogen storage capacities in the low pressure range (p < 42 bar). The defects introduced by fission tracks cannot be probed using sub-critical nitrogen adsorption, as their diameters are much smaller than those of N2 molecules.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article. Raw hydrogen and nitrogen adsorption isotherms are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Züttel, A. Materials for hydrogen storage. Materials today 6, 24–33 (2003).

Sakintuna, B., Lamari-Darkrim, F. & Hirscher, M. Metal hydride materials for solid hydrogen storage: a review. International journal of hydrogen energy 32, 1121–1140 (2007).

Firlej, L., Beckner, M., Romanos, J., Pfeifer, P. & Kuchta, B. Different Approach to Estimation of Hydrogen-Binding Energy in Nanospace-Engineered Activated Carbons. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 118, 955–961 (2014).

Romanos, J. et al. Cycling and Regeneration of Adsorbed Natural Gas in Microporous Mate- rials. Energy & Fuels 31, 14332–14337 (2017).

Rash, T. et al. Microporous carbon monolith synthesis and production for methane storage. Fuel 200, 371–379 (2017).

Romanos, J. et al. High surface area carbon and process for its production. US Patent 9, 517–445 (2016).

Kuchta, B. et al. Open carbon frameworks - a search for optimal geometry for hydrogen storage. Journal of Molecular Modeling 19, 4079–4087 (2013).

Romanos, J., Barakat, F. & Dargham, S. A. Nanoporous Graphene Monolith for Hydrogen Storage. Materials Today: Proceedings 5, 17478–17483 (2018).

DOE. Technical Targets for Onboard Hydrogen Storage for Light-Duty Vehicles, https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/doe-technical-targets-onboard-hydrogen-storage-light-duty-vehicles (2017).

Chae, H. K. et al. A route to high surface area, porosity and inclusion of large molecules in crystals. Nature 427, 523 (2004).

Kuchta, B. et al. Hypothetical high-surface-area carbons with exceptional hydrogen storage capacities: open carbon frameworks. Journal of the American Chemical Society 134, 15130–15137 (2012).

Romanos, J. et al. Infrared study of boron–carbon chemical bonds in boron-doped activated carbon. Carbon 54, 208–214 (2013).

Romanos, J. et al. Nanospace engineering of KOH activated carbon. Nanotechnology 23, 015401 (2012).

Jordá-Beneyto, M., Suárez-García, F., Lozano-Castelló, D., Cazorla-Amorós, D. & Linares- Solano, A. Hydrogen storage on chemically activated carbons and carbon nanomaterials at high pressures. Carbon 45, 293–303 (2007).

Reyhani, A. et al. Hydrogen storage in decorated multiwalled carbon nanotubes by Ca, Co, Fe, Ni, and Pd nanoparticles under ambient conditions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 115, 6994–7001 (2011).

Yang, R. T. Hydrogen storage by alkali-doped carbon nanotubes-revisited. Carbon 38, 623–626 (2000).

Kuchta, B., Firlej, L., Pfeifer, P. & Wexler, C. Numerical estimation of hydrogen storage limits in carbon-based nanospaces. Carbon 48, 223–231 (2010).

Spalaris, C. N., Bupp, L. P. & Gilbert, E. C. Surface Properties of Irradiated Graphite. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 61, 350–354 (1957).

Thrower, P. A. Impurity nucleation of irradiation damage in graphite. Journal of Nuclear Materials 12, 56–60 (1964).

Cadenhead, D. A. Neutron irradiation and surface homogeneity of graphitic materials. Carbon 1, 429–433 (1964).

Chung, T. & Chung, C. C. Increase in the amount of adsorption on modified activated carbon by using neutron flux irradiation. Chemical Engineering Science 54, 1803–1809 (1999).

Chung, T. W. & Chung, C. C. Increase in the amount of adsorption on modified silica gel by using neutron flux irradiation. Chemical Engineering Science 53, 2967–2972 (1998).

Diduszko, R., Swiatkowski, A. & Trznadel, B. J. On surface of micropores and fractal di- mension of activated carbon determined on the basis of adsorption and SAXS investigations. Carbon 38, 1153–1162 (2000).

Setoyama, N., Ruike, M., Kasu, T., Suzuki, T. & Kaneko, K. Surface characterization of microporous solids with. Langmuir 9, 2612–2617 (1993).

Harris, P. J. F., Liu, Z. & Suenaga, K. Imaging the atomic structure of activatedcarbon, Journal of Physics Condensed Matter 20 (2008).

Romanos, J. et al. Engineered porous carbon for high volumetric methane storage. Adsorption Science & Technology 32, 681–691 (2014).

Py, X., Guillot, A. & Cagnon, B. Nanomorphology of activated carbon porosity: Geometrical models confronted to experimental facts. Carbon 42, 1743–1754 (2004).

Yang, S., Hu, H. & Chen, G. Preparation of carbon adsorbents with high surface area and a model for calculating surface area. Carbon 40, 277–284 (2002).

Romanos, J., Dargham, S. A., Roukos, R. & Pfeifer, P. Local Pressure of Supercritical Ad- sorbed Hydrogen in Nanopores. Materials 11, 2235 (2018).

Kaneko, K., Ishii, C., Ruike, M. & Kuwabara, H. Origin of superhigh surface area and micro- crystalline graphitic structures of activated carbons. Carbon 30, 1075–1088 (1992).

Leofanti, G., Padovan, M., Tozzola, G. & Venturelli, B. Surface area and pore texture of catalysts. Catalysis Today 41, 207–219 (1998).

Lastoskie, C., Gubbins, K. E. & Quirke, N. Pore size distribution analysis of microporous carbons: a density functional theory approach. The journal of physical chemistry 97, 4786–4796 (1993).

Jagiello, J. & Olivier, J. P. 2D-NLDFT adsorption models for carbon slit-shaped pores with surface energetical heterogeneity and geometrical corrugation. Carbon 55, 70–80 (2013).

Jagiello, J. & Thommes, M. Comparison of DFT characterization methods based on N2, Ar, CO2, and H2 adsorption applied to carbons with various pore size distributions. Carbon 42, 1227–1232 (2004).

Gennady, Y. G., Matthias, T., Katie, A. C. & Alexander, V. N. Quenched solid density func- tional theory method for characterization of mesoporous carbons by nitrogen adsorption. Carbon 50, 1583–1590 (2012).

Alexander, V. N., Yangzheng, L., Peter, I. R. & Matthias, T. Quenched solid density functional theory and pore size analysis of micro-mesoporous carbons. Carbon 47, 1617–1628 (2009).

Lide, D. R. CRC handbook of chemistry and physics on CD-ROM (CRC Press, 2005).

Steele, W. A. The interaction of gases with solid surfaces (Pergamon Press, Oxford, New York, 1974).

Aranovich, G. L. & Donohue, M. D. Adsorption isotherms for microporous adsorbents. Carbon 33, 1369–1375 (1995).

Aranovich, G. & Donohue, M. D. Adsorption of Supercritical Fluids. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 180, 537–541 (1996).

Bénard, P. & Chahine, R. Modeling of High-Pressure Adsorption Isotherms above the Critical Temperature on Microporous Adsorbents: Application to Methane. Langmuir 13, 808–813 (1997).

Sudibandriyo, M., Mohammad, S. A., Robinson, J. R. L. & Gasem, K. A. M. Ono-Kondo lat- tice model for high-pressure adsorption, Fluid Phase. Fluid Phase Equilibria 299, 238–251 (2010).

Sudibandriyo, M., Mohammad, S. A., Robinson, R. L. & Gasem, K. A. M. Ono–Kondo Model for High-Pressure Mixed-Gas Adsorption on Activated Carbons and Coals. Energy & Fuels 25, 3355–3367 (2011).

Bi, H. et al. Ono–Kondo Model for Supercritical Shale Gas Storage: A Case Study of Silurian Longmaxi Shale in Southeast Chongqing, China. Energy & Fuels 31, 2755–2764 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the U.S. Department of Defense, Navy, NAVSEA Warfare Center, grant number N00164-07-P-1306. LF and BK acknowledge the support from the French National Research Agency (ANR), grant number ANR-14-CE05-0 0 09 HYSTOR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. measured supercritical hydrogen adsorption. T.R. measured subcritical nitrogen adsorption. Boron-doping of activated carbon was performed by M.B. and M.L. Neutron irradiation and prompt- gamma neutron activation analysis were performed by J.D.R. Theoretical modeling of high-binding- energy sites created by fission tracks was performed by L.F., B.K., P.P., and J.R. Ono-Kondo analysis of hydrogen isotherms was performed by J.R., J.R. and M.P. wrote the manuscript while all authors reviewed it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Romanos, J., Beckner, M., Prosniewski, M. et al. Boron-neutron Capture on Activated Carbon for Hydrogen Storage. Sci Rep 9, 2971 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39417-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39417-6

This article is cited by

-

Fabrication of ZnO-doped reduce graphene oxide-based electrochemical sensor for the determination of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol from aqueous environment

Carbon Letters (2024)

-

Integrated approaches for waste to biohydrogen using nanobiomediated towards low carbon bioeconomy

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2023)

-

Green and accurate analytical method for monitoring atropine in foodstuffs as a contaminant and in pharmaceutical samples

Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.