Abstract

This study investigated whether irradiation of a specific light wavelength could affect the sex differentiation of fish. We first found that the photoreceptor genes responsible for receiving red, green, and ultraviolet light were expressed in the eyes of medaka during the sex differentiation period. Second, we revealed that testes developed in 15.9% of genotypic females reared under green light irradiation. These female-to-male sex-reversed fish (i.e. neo-males) showed male-specific secondary sexual characteristics and produced motile sperm. Finally, progeny tests using the sperm of neo-males (XX) and eggs of normal females (XX) revealed that all F1 offspring were female, indicating for the first time in animals that irradiation with light of a specific wavelength can trigger sex reversal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light is one of the important environmental factors for aquatic habitats. Whereas the physiological mechanism of the effects of light, i.e. photoperiod and intensity, in growth and reproduction has been studied in many animal taxa1,2, the knowledge on the effects of the wavelength, i.e. the color of lights, to physiological states of animals is limited. For example, in teleost fish, irradiation by green light stimulates somatic growth by upregulating melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH)3,4. In addition to enhanced growth performance, positive effects on feeding behavior and stress relief have been reported in several fish species by irradiation with specific light wavelength5,6,7,8,9.

In some fish species, environmental factors such as water temperature10,11, pH, rearing density and photoperiod12 affect genotype-dependent sex differentiation and induce sex-reversal13,14. The mechanism of masculinization by high water temperatures has been well studied. In juveniles of the Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) exposed to high water temperatures, overproduced cortisol, a stress marker in fish, directly suppresses the expression of the cyp19a1 gene, which codes for an estrogenic enzyme that converts androgen to estrogen and subsequently induces masculinization15. In addition to this stress-induced sex-reversal mechanism, it has recently been reported that masculinization caused by exposure to high water temperatures in the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) results from an increase in the cyp19a promoter methylation level in females, indicating that water temperature-induced masculinization involves DNA methylation-mediated control of aromatase gene expression16. Although the fundamental mechanism of environmental sex determination (ESD) by temperature has been studied at the molecular levels, nothing is known about the effects of specific light wavelengths on gonadal development and sex differentiation.

Medaka (Oryzias latipes) is a small model fish with several desirable features, including a short generation time, small genome size, and the availability of an inbred strain, Hd-rRII1, showing genotypic sex-dependent body color17,18. Their sex determination system is male heterogametic (XY/XX). A sex determining gene named dmy/dmrt1bY (DM-domain gene on Y chromosome) has been identified on the Y chromosome19,20,21. In the Hd-rRII1 strain, body color is different in males and females. The allele R of the r locus (a sex-linked pigment gene) is located on the Y chromosome. In this strain, XrXr females have a white body color, whereas XrYR males have an orange-red body color21. Therefore, it is easy to detect sex-reversed fish by observation of phenotypic sex (i.e. sex of gonads and secondary sexual characteristics appearing on fins) and determination of genotypic sex (i.e. genomic PCR for the dmy gene and body color). In addition, medaka normally follow a strong genetic sex determination system that is not easily influenced by environmental factors22. However, the induction of sex-reversal by administration of sex-steroid hormone, exposure to high water temperature, and the regulation of primordial germ cell number has been demonstrated10,15,23,24,25,26,27. These reports suggest that artificial sex control is possible in this species. Therefore, we selected medaka for molecular genotypic analysis of sex-reversal induced by irradiation with specific light wavelengths.

Rod and cone photoreceptor cells of the retina enable the detection of light and the initiation of visual signaling17. Cone photoreceptors become functional under the sufficient light condition and they are related to the color vision. The spectral range of detection is controlled by the selected expression of visual pigments differing in absorption spectra in cone photoreceptor cells. Cone opsins, which belong to the subfamily of G-protein-coupled transmembrane receptors and form wavelength-specific visual pigments together with retinal chromophores, play key roles in color discrimination and in the appropriate processing of post-receptor signals17,18,28. Fish possess many cone opsin gene orthologs responsible for photoreception, which have emerged though gene duplication and allow fishes to adapt to the various light conditions of the aquatic environment29. In the retinas of adult medaka, 8 cone opsin genes, such as ultraviolet (SWS1), blue (SWS2-A, SWS2-B), green (RH2-A, RH2-B, RH2-C), and red (LWS-A and LWS-B) are responsible for photoreception with retinal chromophores and have already been identified30. However, it has not been revealed which opsin genes are expressed in the eyes of medaka during the sex differentiation stage.

In the present study, we first investigated opsin gene expression in the eyes of 3 day after hatched medaka embryos. To test whether irradiation of a specific wavelength could affect sex differentiation in medaka, newly hatched medaka embryos were reared under white and green light-emitting diodes (LED) for 3 months. The male-to-female and female-to-male sex reversal rates were studied by comparing the phenotypic sex with the genotypic sex. To confirm whether the sex-reversal was functional or not, a progeny test was conducted by artificial insemination, and the development and sex of F1 offspring were analyzed.

Results

Green opsin genes were expressed in eyes of newly hatched Hd-rRII1 medaka

All 8 opsin genes were expressed in the eyes at the adult stage, whereas only 5 opsin genes were expressed in the eyes at the 3 day after hatch (Fig. 1C). The ultraviolet opsin gene (SWS1), all three types of green opsin genes (RH2-A, RH2-B, RH2-C), and two type of two red opsin genes (LWS-A/LWS-B) were expressed in the eyes of 3 day after hatched medaka (Fig. 1C). In contrast, two types of blue opsin genes (SWS2-A and SWS2-B) were not expressed at the 3 day after hatch medaka (Fig. 1C).

Rearing conditions and opsin gene expression of newly hatched medaka. (A) White LED shows two peaks at 451 and 581 nm. Green LED shows one peak at 518 nm. (B) Experimental schedule. White and green LED irradiations started from just after hatching (0 dph) to 60 dph. Fish were sampled at 60 dph for gonadal histology and genotyping. Progeny tests were conducted at 90 dph by artificial insemination. (C) RT-PCR analysis of 8 opsin genes and ef-1a in the eyes of 3 dph and adult medaka. The λmax values for each opsin protein are from Matsumoto et al. 200630.

Appearance of genotypic females showing male-specific phenotypes

The experimental fish showed a high survival rate in each LED irradiation treatment (over 80%) at 60 dph. In both white and green LED treatment groups, dmy and dmrt1 genes were detected in all orange-red body colored individuals, while only the dmrt1 gene was detected in white body colored individuals by genomic DNA PCR (Fig. 2A,B), indicating that the body color represented the genotypic sex even if the fish were reared under green LED irradiation.

Determination of genotypic and phenotypic sex by body color, genomic DNA PCR, and the secondary sexual characteristics of dorsal and anal fins. (A,B) Genotypes of white and orange-red body color of 60-dph Hd-rRII1 medaka reared under white LED (A) and green LED (B). A primer set designed for the conserved region of dmy, a sex determination gene on the Y chromosome, and dmrt1, an orthologue of dmy located on an autosome, were used for PCR analysis. Fin clips of adult males and females were used as positive controls. DW; distilled water for negative control. MW; molecular weight marker. (C) Genotypic female (white body color) showing female-specific fin types under green LED irradiation. An uncut dorsal fin (arrow) and a round-shaped anal fin (dotted line) are secondary sexual characteristics of females. (D) Genotypic male (orange-red body color) showing male-specific fin types under green LED irradiation. A deeply cut dorsal fin (arrow) and a parallelogram-shaped anal fin (dotted line) are secondary characteristics of males. (E) Genotypic female (white body color) showing secondary characteristics of males, i.e. a deeply cut dorsal fin (arrow) and a parallelogram-shaped anal fin (dotted line). (F–H) External observation of the gonads of green LED-irradiated medaka (C–E). Dotted lines show ovary (F) and testes (G,H). (I–K) Histological observation of gonads of green LED-treated medaka (C–E). Perinucleolar oocytes (arrows in I) in ovaries and spermatogenic cells (arrows in J) were observed. Spermatogenic cells (arrows) including spermatozoa (arrowheads) were observed in female-to-male sex-reversed medaka testes (K). Scale bars = 2 mm (C–H), 40 μm (I–K).

In the green LED treatment group, all genotypic males (dmy+/−, orange-red body color) had spermatogenic testes and male-specific anal and dorsal fins (n = 40) (Fig. 2D,G,J, Table 1). Notably, the fish showed male-specific secondary sex characteristics, i.e. parallelogram-shaped anal fins and deeply cut dorsal fins, which were observed in 15.9% of genotypic females (dmy−/−, white body color, n = 7) (Fig. 2E). External and histological observation revealed that those fish possessed testes, spermatogenic germ cells and mature spermatozoa (Fig. 2H,K) (Supplementary Fig. 4). The other 84.1% of genotypic females (n = 37) possessed female-specific fin types, ovaries, and oocytes (Fig. 2C,F,I, Table 1). The appearance rate of sex-reversed fish under green LED treatment was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than under white LED treatment (Table 1). No sex-reversed fish was observed in the white LED irradiation group (n = 38, Table 1).

Sex-reversed males (XX) produced functional spermatozoa and all-female F1 offspring

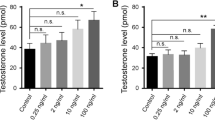

Motile sperm was obtained from sex-reversed males (white body color, dmy−/−, male-specific fin types) (n = 2, Fig. 3A) (Supplementary Movie 1). The spermatozoa were morphologically indistinguishable from those of normal males (Fig. 3B). The density of spermatozoa of the sex-reversed males was approximately 50% lower than that of normal males (Fig. 3C). Genomic DNA PCR analysis revealed that the dmy gene was detected neither in sperm nor in the fins of sex-reversed males (Fig. 3D).

Progeny test of sperm obtained from sex-reversed males. (A) A sex-reversed male showing a female genotype (dmy−/−), female-specific white body color, and male-specific secondary sexual characteristics in fins (a parallelogram dorsal fin and a deeply cut anal fin, arrows). (B) Spermatozoa obtained from a sex-reversed male (left) were morphologically normal and indistinguishable from those of a normal male (right). (C) Density of spermatozoa of normal males (n = 3) and a sex-reversed male (n = 2). P < 0.05. (D) Genomic DNA PCR of the sperm (Sp) and a fin (Fin) of a sex-reversed male using a primer set for dmy/dmrt1 genes. (E) Genomic DNA PCR for F1 offspring obtained from sex-reversed males (n = 2) (lanes 1–9) using a primer set for dmy/dmrt1 genes. Fin clips of adult males and females were used for positive controls. DW, distilled water for negative control; MW, molecular weight marker. (F) Histological observation of a gonad of F1 offspring. Dotted line shows an ovary. Scale bars = 2 mm (A), 10 mm (B), 0.5 mm (F).

To test whether sex-reversed males could show sexual behavior, each male (n = 2) was paired with normal females (n = 7) and reared in optimal spawning conditions for one month. However, no sexual behavior and spawning was observed. Therefore, we conducted artificial insemination using sperm stripped from sex-reversed males (dmy−/−) and eggs from normal females (dmy−/−). Genomic PCR analysis revealed that none of the F1 offspring analyzed (n = 18) possessed dmy (Fig. 3E). Gonadal histology revealed that all of the F1 offspring (n = 18) at 2-months-old possessed ovaries (Fig. 3F).

Discussion

In this study, we found that irradiation with green LED light during the sex differentiation period induced female-to-male sex-reversal production of fertile sperm in genotypic female, indicating for the first time in animals that irradiation of a specific wavelength can be a trigger for sex reversal.

In the wild, the frequency of female-to-male sex-reversal in medaka is 0.98% in Japan (Northern and Southern populations), China, and West and East Korea31. The female-to-male sex-reversal rate of the Hd-rRII1 strain (15.9%) obtained in this study was much higher than that observed in wild populations. Spontaneous XX male were also reported in inbred strain medaka32. However, spontaneous XX male was not observed in this experiment. In addition, female-to-male sex-reversal induced by green LED irradiation was not observed in the commercially available orange-red variety (data not shown). It has been reported that, in high water temperature treatment, the female-to-male sex-reversal rate varies among strains (e.g. 50% in the HNI strain and 24% in the Hd-rRII1 strain)10. Therefore, differences of genetic and epigenetic background could influence sex reversal rates resulting from green LED irradiation. Further studies are needed to test whether UV and red light can affect gonadal differentiation, because the opsin genes responsible for photoreception of these wavelengths (SWS1 and LWS-A) were expressed in the eyes of 3 day after hatch medaka. Other factors of larval rearing conditions, such as the irradiation period and light intensity, need to be investigated to reveal the requirements for successful sex-reversal and obtain higher sex-reversal rates.

In this study, irradiation of green LED light was tested based on the opsin gene expression profile in the eyes of 3 day after hatched medaka. However, photoreceptors exist not only in the retina, but also in the pineal gland and deep brain of medaka33. In Oncorhynchus masou, the saccus vasculosus, which is located in the deep brain, is known to express the rhodopsin family genes RH1, SWS1, LWS, and OPN4 and regulate photoperiod gonadal development2. Interestingly, in the jellyfish Clytia gregaria, it was revealed that the gonadal photoreceptor known as opsin 9 regulates gonadal development34. Thus, it could be that known and unknown photoreceptive organs influence sex differentiation in fish35. An important issue raised by this study is which photoreceptive organ that received the green light induced the female-to-male sex-reversal in medaka.

The mechanism by which female-to-male sex reversal occurred via green light in medaka was not revealed in this study. According to our results, two hypotheses were proposed. In medaka, sex reversal can be induced by exposure to high water temperature10,15,23,24,35. The expression of the gr gene encoding a glucocorticoid receptor, a stress marker, is increased by exposure to high water temperature during the sex differentiation period15. Thus, it has been proposed that overproduction of glucocorticoid suppresses cyp19a, a key aromatase gene that converts androgen to estrogen and induces female-to-male sex-reversal15,35. One possibility is that the stress caused by a specific light wavelength induced elevated cortisol levels and consequently suppressed aromatase gene expression in our study. Another possibility is that the effect of cell death induced sex reversal via irradiation of a specific wavelength. In insects, the common fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, house mosquito Culex pipiens molestus, confused flour beetle Tribolium confusum, and strawberry leaf beetle Galerucella grisescens are killed by irradiation with visible blue light36,37. These studies suggest that irradiation with blue light produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induces cell death. In normal gonadal development of medaka, genotypic females possess 5 times more germ cells at 10 dph than genotypic males23. The depletion of germ-cell numbers by RNA knockdown can induce female-to-male sex-reversal26,27, suggesting that the number of germ cells in embryonic gonads is a factor for phenotypic sex differentiation of medaka. Therefore, if excessive irradiation with a specific wavelength of light can produce ROS, it might suppress germ cell division and induce female-to-male sex-reversal.

In many species of cultured finfish, females exhibit higher growth rates than males and attain larger sizes, because the males are often sexually mature before reaching marketable size and show retarded growth rates. For example, Paralichthys olivaceus and Nibea albiflora females grow faster than males38,39. In the sturgeon family, their eggs (i.e. caviar) have high value in the market40,41. Therefore, sex manipulation of fish and monosex culture of females is desirable for commercial operations42,43,44. In the case of male heterogametic species, gynogenesis followed by androgenic hormonal sex reversal of females into males theoretically allows for the production of 100% sex-reversed XX males45,46. Conventional techniques for practical sex-reversal are the treatment of sexually undifferentiated fry by offering feed treated with or immersion with hormones or hormone analogues, which has been shown to work well under carefully controlled conditions in a wide range of species47. However, excessive doses of some hormones can lead to sterility or abnormal gonadal development. In addition, concerns persist over the safety of commercial sex reversal treatments both with regard to the safety of the farmer and of the consumer together with possible environmental impacts. If irradiation with a specific wavelength of light could induce neo-males in other aquaculture target species, we can expect the establishment of a new sex manipulation system that is safer and less costly than using sex hormones.

Materials and Methods

Animals and ethics

The HdrR-II1 (Strain ID: IB178) inbred strain of medaka, supplied by NBRP Medaka (https://shigen.nig.ac.jp/medaka/), was used for all experiments. The animal experiments in this study were approved by the Kagoshima university animal experiment committee and all experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of Kagoshima university.

Opsin gene expression of juvenile medaka

Eight cone opsin genes, LWS-A/LWS-B, RH2-A, RH2-B, RH2-C, SWS1, SWS2-A, and SWS2-B, have been reported in medaka30. The expression of opsin genes in the eyes of newly hatched embryo medaka (3 days post-hatching, dph) of the Hd-rRII1 inbred strain was analyzed by RT-PCR. Each opsin gene primer was from Matsumoto et al.30 and Chinen et al.48. LWS-A and LWS-B genes were highly similar coding30,49. Therefore, we used only LWS-A primer set. The total RNA was extracted from the eyes after homogenization in a 1.5-ml tube with 1000-μl Tri Reagent (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd. Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A ReverTra Ace kit (ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover; Toyobo Co., Ltd. Japan) was used for cDNA synthesis, and BIOTAQ DNA polymerase (Bioline Ltd. United Kingdom) was used for RT-PCR. PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 30 sec, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 55 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 1 min, and 80 °C for 8 sec.

Rearing condition of medaka

The fish were reared under each color of LED (LDA6-G and LB1526G, Beamtec Co., Ltd. Saitama, Japan) in rectangular parallelepiped glass tanks (31.5 × 18.5 × 24.4 cm) covered by shielding curtains. The distance from the water surface to the light was approximately 5 cm. The light wavelength peaks were predetermined by an illuminance spectrophotometer (CL-500A; Konica Minolta, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and were 450 nm for the white LED and 518 nm for the green LED (Fig. 1A). The photoperiod in the rearing term was controlled at 14-h light and 10-h dark, and water temperate was maintained at 26 ± 5 °C. The formula food (Kyorin Co., LTD, Hyogo, Japan) and Artemia nauplii hatched from commercialized eggs (Brine Shrimp EGGS-90, Kitamura co., ltd, Kyoto, Japan) were fed to fish from newly hatched to adult. Each LED was used to irradiate fish tanks from 0 to 60 dph. Progeny tests were performed at 90 dph (Fig. 1B).

Determination of genotypic sex of medaka

The genotypic sex of medaka was determined by genomic DNA PCR for the dmy gene and the observation of body color. A 25-mm2 sample of caudal fin was dissolved in 500 μl of cell lysis regent (100 mM Tris-Cl, 5 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2% SDS, 1 μl Proteinase K) at 55 °C for 12 h in an incubator. After 10 min of centrifugation at 13,000 × g, the supernatant was mixed with 500 μl of isopropanol, and the precipitant was washed with 70% alcohol. The genomic DNA was eluted with TE buffer. The genomic DNA PCR primers were from Matsuda et al.20. One primer set can detect two genes that are dmy (1000 bp) and dmrt1 (1400 bp). Because dmy only exists in males and dmrt1 exists in both sexes, genotypic males show two bands and genotypic females show one band by genomic DNA PCR. BIOTAQ DNA polymerase was used for genomic DNA PCR. PCR conditions were as follows: 96 °C for preheating and 94 °C for 2 min, then 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 7 min. In the Hd-rRII1 strain, genotypic males and females show orange-red and white body color, respectively. Therefore, body color was used to discriminate the genotypic sex of this inbred strain. As an internal control, the ef-1α primer set was used according to Nakamoto et al.50.

Determination of phenotypic sex of medaka

The phenotypic sex was determined with gonadal histology and observation of shapes of dorsal and anal fins. The shapes of the anal and dorsal fins represent the secondary sex characteristics of medaka51. Phenotypic females show round and short anal fins (Fig. 2C), but phenotypic males show sharp and long anal fins (Fig. 2D). In addition, the dorsal fins of phenotypic males are deeply cut (inset of Fig. 2D), but those of phenotypic females are uncut (inset of Fig. 2C).

The gonads were fixed in Bouin’s fixatives at 4 °C in a refrigerator. The fixed gonads were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol from 70% to 100% and cleared by xylene. In all processes, a shaker (Wave-SI; Taitec Co., Japan) was used. The gonads were embedded in paraffin and sectioned from 4 to 6 μm by a microtome (HM 315 S; MICROM international GmbH, Ltd. Germany). The sections were stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The sections were deparaffinized for 5 min in xylene and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol from 99% to 70%. The sections stained with hematoxylin for 2 min and eosin for 10 min were washed in tap water. Finally, the sections were stained with eosin and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol from 70% to 99% and mounted by cover glass with encapsulating material (Entellan New; Merck & Co., USA).

Counting of spermatozoa and progeny tests by artificial insemination

The sperm was obtained from anesthetized sex-revered males and normal males. The spermatozoa were counted three times in each fish by a hemocytometer (Burker-Turk; Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC, USA).

For artificial insemination, mature sex-reversed fish (HdrR-II1) and intact females (orange-red variety) were separately reared in glass tanks in spawning conditions as described above. The sperm were obtained from sex-reversed fish with abdominal pressure. The unfertilized eggs were obtained from anesthetized females. Those eggs and spermatozoa were mixed in wells of 6-well culture plates with artificial Iwamatsu’s seminal plasma (pH 7.3)52. The fertilized eggs were reared at 26 °C, and the obtained newly hatched embryos were reared for two months. The genotypic and phenotypic sex of the F1 offspring were determined as described above.

Statistics

Fisher’s exact test was used for the appearance rate of sex-reversed fish and the sex ratio of F1 offspring. T-tests were used for spermatozoa counts. All data were analyzed using the statistical analysis software Stat View 5.0) SAS Institute Inc. NC, USA).

References

Nakane, Y. et al. A mammalian neural tissue opsin (Opsin 5) is a deep brain photoreceptor in birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 15264–15268 (2010).

Nakane, Y. et al. The saccus vasculosus of fish is a sensor of seasonal changes in day length. Nature Communications 4, 1–7 (2013).

Yamanome, T., Mizusawa, K., Hasegawa, E. & Takahashi, A. Green Light Stimulates Somatic Growth in the Barfin Flounder Verasper moseri. Journal of Experimental Zoology 79, 73–79 (2009).

Takahashi, A., Kasagi, S., Murakami, N., Furufuji, S. & Kikuchi, S. Chronic effects of light irradiated from LED on the growth performance and endocrine properties of barfin flounder Verasper moseri. General and Comparative Endocrinology 232, 101–108 (2016).

Karakatsouli, N. et al. Effects of light spectrum on growth and stress response of rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss reared under recirculating system conditions. Aquacultural Engineering 38, 36–42 (2008).

Villamizar, N., García-Alcazar, A. & Sánchez-Vázquez, F. J. Effect of light spectrum and photoperiod on the growth, development and survival of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) larvae. Aquaculture 292, 80–86 (2009).

Papoutsoglou, S. E., Karakatsouli, N., Papoutsoglou, E. S. & Vasilikos, G. Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) response to two pieces of music (‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’ and ‘Romanza’) combined with light intensity, using recirculating water system. Fish Physiology and Biochemistry 36, 539–554 (2010).

Shin, H. S., Lee, J. & Choi, C. Y. Effects of LED light spectra on oxidative stress and the protective role of melatonin inrelation to the daily rhythm of the yellowtail clownfish, Amphiprion clarkii. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - A Molecular and Integrative Physiology 160, 221–228 (2011).

Shin, H. S. & Choi, C. Y. The stimulatory effect of LED light spectra on genes related to photoreceptors and skin pigmentation in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Fish Physiology and Biochemistry 40, 1229–1238 (2014).

Sato, T., Endo, T., Yamahira, K., Hamaguchi, S. & Sakaizumi, M. Induction of female-to-male sex reversal by high temperature treatment in Medaka. Oryzias latipes. Zoological science 22, 985–8 (2005).

Baroiller, J. F., D’Cotta, H., Bezault, E., Wessels, S. & Hoerstgen-Schwark, G. Tilapia sex determination: Where temperature and genetics meet. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - A Molecular and Integrative Physiology 153, 30–38 (2009).

Brown, E. E., Baumann, H. & Conover, D. O. Temperature and photoperiod effects on sex determination in a fish. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 461, 39–43 (2014).

Devlin, R. H. & Nagahama, Y. Sex determination and sex differentiation in fish: An overview of genetic, physiological, and environmental influences. Aquaculture 208, 191–364 (2002).

Baroiller, J. F. & D’Cotta, H. The Reversible Sex of Gonochoristic Fish: Insights and Consequences. Sexual Development 10, 242–266 (2016).

Yamaguchi, T., Yoshinaga, N., Yazawa, T., Gen, K. & Kitano, T. Cortisol is involved in temperature-dependent sex determination in the Japanese flounder. Endocrinology 151, 3900–3908 (2010).

Navarro-Martín, L. et al. DNA methylation of the gonadal aromatase (cyp19a) promoter is involved in temperature-dependent sex ratio shifts in the European sea bass. PLoS Genetics 7 (2011).

Terakita, A. The opsins. Genome Biology 6, 1–9 (2005).

Shichida, Y. & Matsuyama, T. Evolution of opsins and phototransduction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364, 2881–2895 (2009).

Nanda, I. et al. A duplicated copy of DMRT1 in the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome of the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99, 1–6 (2002).

Matsuda, M. et al. DMY is a Y-specific DM-domain gene required for male development in the medaka fish. Nature 399, 559–563 (2002).

Matsuda, M. et al. DMY gene induces male development in genetically female (XX) medaka fish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 3865–3870 (2007).

Aida, T. On the Inheritance of Color in a Fresh-Water Fish, APLOCHEILUS LATIPES Temmick and Schlegel, with Special Reference to Sex-Linked Inheritance. Genetics 6, 554–573 (1921).

Selim, K. M., Shinomiya, A., Otake, H., Hamaguchi, S. & Sakaizumi, M. Effects of high temperature on sex differentiation and germ cell population in medaka. Oryzias latipes. Aquaculture 289, 340–349 (2009).

Hattori, R. S. et al. Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination in Hd-rR Medaka Oryzias latipes: Gender Sensitivity, Thermal Threshold, Critical Period, and DMRT1. Sexual Development 8477, 138–146 (2007).

Paul-Prasanth, B. et al. Estrogen oversees the maintenance of the female genetic program in terminally differentiated gonochorists. Scientific Reports 3 (2013).

Kurokawa, H. et al. Germ cells are essential for sexual dimorphism in the medaka gonad. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 16958–16963 (2007).

Morinaga, C. et al. The hotei mutation of medaka in the anti-Mullerian hormone receptor causes the dysregulation of germ cell and sexual development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 9691–9696 (2007).

Futahashi, R. et al. Extraordinary diversity of visual opsin genes in dragonflies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, E1247–E1256 (2015).

Cortesi, F. et al. Ancestral duplications and highly dynamic opsin gene evolution in percomorph fishes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 1493–1498 (2015).

Matsumoto, Y., Fukamachi, S., Mitani, H. & Kawamura, S. Functional characterization of visual opsin repertoire in Medaka (Oryzias latipes). Gene 371, 268–278 (2006).

Shinomiya, A. et al. Field Survey of Sex-Reversals in the Medaka, Oryzias latipes: Genotypic Sexing of Wild Populations. Zoological Science 21, 613–619 (2004).

Nanda, I., Hornung, U., Kondo, M., Schmid, M. & Schartl, M. Common spontaneous sex-reversed XX males of the medaka Oryzias latipes. Genetics 163, 245–251 (2003).

Fischer, R. M. et al. Co-Expression of VAL- and TMT-Opsins Uncovers Ancient Photosensory Interneurons and Motorneurons in the Vertebrate Brain. PLoS Biology 11 (2013).

Quiroga Artigas, G. et al. A gonad-expressed opsin mediates light-induced spawning in the jellyfish clytia. eLife 7, 1–22 (2018).

Kitano, T., Hayashi, Y., Shiraishi, E. & Kamei, Y. Estrogen Rescues Masculinization of Genetically Female Medaka by Exposure to Cortisol or High Temperature. Molecular Reproduction and Development 79, 719–726 (2012).

Hori, M., Shibuya, K., Sato, M. & Saito, Y. Lethal effects of short-wavelength visible light on insects. Scientific Reports 4, 1–6 (2014).

Hori, M. & Suzuki, A. Lethal effect of blue light on strawberry leaf beetle, Galerucella grisescens (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Scientific Reports 7, 1–6 (2017).

Yamamoto, E. Studies on sex-manipulation and production of cloned populations in hirame, Paralichthys oliuaceus (Temminck et Schlegel). Aquaculture 173, 235–246 (1999).

Xu, D. et al. Production of neo-males from gynogenetic yellow drum through 17α-methyltestosterone immersion and subsequent application for the establishment of all-female populations. Aquaculture 489, 154–161 (2018).

Fopp-Bayat. Genome Manipulation and Sex Control in the Siberian Sturgeon: An Updated Synthesis with Regard to Objectives, Constraints and Findings. In: Williot P., Nonnotte G., Chebanov M. (eds) The Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser baerii, Brandt, 1869) Volume 2 - Farming. Springer, Cham (2018).

Vizziano-Cantonnet, D., Lasalle, A., Di Landro, S., Klopp, C. & Genthon, C. De novo transcriptome analysis to search for sex-differentiation genes in the Siberian sturgeon. General and Comparative Endocrinology 268, 96–109 (2018).

Frisch, A. Sex-change and gonadal steroids in sequentially-hermaphroditic teleost fish. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 14, 481–499 (2004).

Budd, A., Banh, Q., Domingos, J. & Jerry, D. Sex Control in Fish: Approaches, Challenges and Opportunities for Aquaculture. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 3, 329–355 (2015).

Goikoetxea, A., Todd, E. V. & Gemmell, N. J. Stress and sex: does cortisol mediate sex change in fish? Reproduction 154, 149–160 (2017).

Yamazaki, F. Sex control and manipulation in fish. Aquaculture 33, 329–354 (1983).

Jensen, G. L., Shelton, W. L., Yang, S. & Wilken, L. O. Sex Reversal of Gynogenetic Grass Carp by Implantation of Methyltestosterone. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 112, 79–85 (1983).

Sakshin, B., Thanyada, S., Tuantranont Adisorn, J. K. & James, R. R. Monosex-Male Sex Reversal of Nile Tilapia Eggs Using Pulse-Electric Field Inductions. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 12, 724–728 (2015).

Chinen, A., Hamaoka, T., Yamada, Y. & Kawamura, S. Gene duplication and spectral diversification of cone visual pigments of zebrafish. Genetics 163, 663–675 (2003).

Shimmura, T. et al. Dynamic plasticity in phototransduction regulates seasonal changes in color perception. Nature Communications 8, 1–7 (2017).

Nakamoto, M., Matsuda, M., Wang, D. S., Nagahama, Y. & Shibata, N. Molecular cloning and analysis of gonadal expression of Foxl2 in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 344, 353–361 (2006).

Iwamatsu, T. Stages of normal development in the medaka Oryzias latipes. Mechanisms of development 121, 605–618 (2004).

Iwamatsu, T. Studies on Oocyte Maturation inthe Medaka, Oryzias latipes. Improvement of Culture Medium for Oocytes in Vitro. Japanese Journal of Ichthyology 20, 218–224 (1973).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. A. Yamamoto, M. Matsumoto, T. Sasaki, R. Takase and A. Yoshinari of Kagoshima University for supporting experiments. We are grateful to NBRP Medaka (https://shigen.nig.ac.jp/medaka/) for providing Hd-rRII1 (Strain ID: IB178).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T. and T.K. designed research; O.H. performed research; O.H., Y.T. and T.K. wrote the paper. Y.T., K.S., K.A. and T.K. reviewed manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayasaka, O., Takeuchi, Y., Shiozaki, K. et al. Green light irradiation during sex differentiation induces female-to-male sex reversal in the medaka Oryzias latipes. Sci Rep 9, 2383 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38908-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38908-w

This article is cited by

-

Circular RNA expression profiles and CircSnd1-miR-135b/c-foxl2 axis analysis in gonadal differentiation of protogynous hermaphroditic ricefield eel Monopterus albus

BMC Genomics (2022)

-

Profile of gene expression changes during estrodiol-17β-induced feminization in the Takifugu rubripes brain

BMC Genomics (2021)

-

Comparison of differential expression genes in ovaries and testes of Pearlscale angelfish Centropyge vrolikii based on RNA-Seq analysis

Fish Physiology and Biochemistry (2021)

-

Activation of stress response axis as a key process in environment-induced sex plasticity in fish

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.