Abstract

Predicting how species will respond to climate change and land use modification is essential for conserving organisms and maintaining ecosystem services. Thermal tolerances have been shown to have strong predictive power, but the potential importance of desiccation tolerances have been less explored in some species. Here, we report measurements of thermal and desiccation tolerances and safety margins across a gradient of urbanization, for three bee species: silky striped sweat bees (Agapostemon sericeus), western honeybees (Apis mellifera), and common eastern bumblebees (Bombus impatiens). We found significant differences in thermal tolerances, measured as critical thermal maximum (CTmax), amongst species. Bumblebees were the least sensitive to warming, with a higher CTmax (53.1 °C) than sweat bees (50.3 °C) and honeybees (49.1 °C). We also found significant differences in desiccation tolerances, measured as critical water content (CWC), between all species. Sweat bees were the least sensitive to desiccation, with the lowest CWC (51.7%), followed by bumblebees (63.7%) and honeybees (74.2%). Moreover, bumblebees and sweat bees were closer to their CTmax in more urbanized locations, while honeybees were closer to their CWC. These results suggest that bees have differential sensitivities to environmental change and managing for diverse bee communities in the face of global change may require mitigating both changes in temperature and water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change and land use modification can have negative consequences for many species, leading to local population declines1,2,3 and extinctions4. When certain taxa decline, the services they provide (e.g. pollination) can be disturbed or degraded5,6. While examples of population declines with climate change and land-use modification are accumulating1,2,3,7, proximate mechanisms mediating these declines are often unclear because very species-specific patterns occur. Understanding these mechanisms is vital to identifying actions that mitigate the potential losses of ecosystem services. Multiple studies have identified the importance of physiological tolerances in predicting species responses to global change3,8,9,10,11, as these tolerances demarcate the environmental conditions necessary for survival. However, the majority of studies investigating physiological tolerances focus on thermal tolerances12,13,14, while desiccation tolerances may be just as important.

Thermal tolerances are an important tool for investigating species responses to changes in temperature15,16,17. Critical thermal maximum (CTmax) and minimum (CTmin), and thermal safety margins are the most common metrics of physiological vulnerability to climate change for a variety of organisms13,18,19. CTmax is an organism’s upper sub-lethal temperature and CTmin the lower sub-lethal temperature20, and these are the temperatures at which an organism loses muscular control and suffers an ecological death. The difference between CTmax and CTmin is defined as the thermal range21. Thermal safety margin is defined as the differences between CTmax and either optimal body temperature, field body temperature, or air temperature, and offers a metric for understanding vulnerabilities to warming8. In general, thermal tolerance has been found to vary with natural temperature gradients. Insects from high and low latitudes tend to have similar CTmax values, while CTmin declines with latitude18,22 and thermal safety margin increases with latitude18. CTmax has been shown to decreases with altitude13,23. There is also evidence that insect thermal tolerance varies across smaller climatic gradients24. Body size (surface-volume ratios) may also influence thermal tolerance, because smaller animals dissipate heat better but may be more prone to desiccation25.

Desiccation tolerances may also be an important mediator of climate effects on species26, but few studies have explored desiccation in this context27,28,29,30, and little information exists about desiccation tolerance of animals in general31,32,33,34,35. Hadley34 reported that the majority of arthropods maintain a water content between 65 and 75%, while some arthropods may survive with a water content as low as 40%31. We know little about how desiccation tolerance varies with environmental gradients, but Hoffman et al.27 suggest that fruit fly desiccation tolerance declines with increasing precipitation in Australia. Weldon et al.36 provide evidence that desiccation tolerance varies geographically among populations of Mediterranean fruit flies. Moreover, McCluney et al. (2017) found that arthropod hydration decreased with urbanization and consequent warming in moist/mild cities (Raleigh, NC), but sometimes increased with urbanization in warmer cities (Phoenix, AZ; Orlando, FL). The observed variations in desiccation tolerance may be due to local adaptations, or plasticity37. These studies suggest that desiccation tolerance might be an important predictor of the effects of land use and climate change on animals. Desiccation may be particularly likely for smaller animals, like insects, due to their greater surface area to volume ratios and higher water loss relative to metabolic rate38.

Multiple metrics of desiccation tolerance have been employed by others. Many studies have used the time until 50% of the animals die (LT50)27,39 for both desiccation and thermal tolerance measurements. However, another measure, body water content at death (critical water content, CWC), provides values comparable across studies. CWC is an experimental measurement of desiccation tolerance, or the lethal water content, calculated gravimetrically as the difference between wet and dry mass, divided by wet mass40. Unlike thermal safety margins, none have calculated a hygric safety margin (hygric = relating to moisture), which we have used in this study and define here as the difference between CWC and field body water content. This metric could be highly informative in predicting potential responses to climate change, complementing thermal analogs.

Urban environments are unique systems for examining how land use modification and climate change influence thermal and desiccation tolerances41. Summer urban heat islands (UHIs) in the USA typically generate a mosaic of hotter and cooler locations that differ, on average, by 1–4 °C from each other and form cooler, rural temperatures42. The intensity of UHIs is often influenced by the biome in which the city is located. Urban areas within regions dominated by temperate and mixed forest can experience temperature increases of 8 °C, while urban areas within desert regions experience less pronounced changes or temperature decreases in urban centers43. UHIs provides a gradient of temperatures44,45 that can replicate projected climate change41. Urban areas can also experience altered soil moisture46, and soil moisture is found to vary among habitat types within and among cities47. These changes in temperature and moisture availability can impact the field body water content of arthropods48. A recent study by Hamblin et al. (2017) found CTmax to predict population change for 15 bee species across an urbanization gradient. We know relatively little about bee thermal tolerances13,15,49,50, and even less about the desiccation tolerances of bees49, even though these factors may provide strong predictive power in explaining population declines or changes in distributions. Elevated temperatures due to UHI effects are likely to increase desiccation threats. Others have found that changes in insect water balance can have consequences on growth, reproduction, and survival51.

Here we examine how a gradient of urbanization (impervious surface, e.g. areas of pavement), in a medium-sized city, alters both the CTmax and CWC of three bee species: the silky striped sweat bee (Agapostemon sericeus), the western honeybee (Apis mellifera), and the common eastern bumblebee (Bombus impatiens). We combine measurements of thermal and water content limits with measurements of field body temperature and field water content, to quantify thermal and hygric safety margins. We test the relative importance of two competing hypotheses about limits and safety margins. First, thermal and water content limits may change rapidly within taxa due to changes in temperature and moisture conditions, with sensitivity decreasing with urbanization-induced warming and drying. In this case, thermal and hygric safety margins would not vary with urbanization because limits change in concert with field body temperature and water content (“shifting limits hypothesis,” i.e. limits are plastic). Second, thermal and water content limits may change slowly within taxa, being insensitive to urbanization-induced warming and drying. In this case, limits would not change with urbanization, even as average field body temperature or water content did change, and we would expect safety margins to be related to urbanization-induced warming or drying (“stable limits hypothesis,” i.e. limits are non-plastic).

Materials and Methods

Study Area

Field body temperature and water content were measured in bees collected from 19 sites, and CTmax and CWC were measured on bees collected from a subset of sites, across the metropolitan region of Toledo, Ohio, USA (Fig. 1). Toledo has been shown to display urban heat island effects with 2 °C warmer mean annual temperatures52. Toledo has a 622.6 square-kilometer metropolitan area with a population of 507,643 residents and a large network of greenspaces (125 city parks and 150 urban gardens)53 that were used as sampling locations52 Sites were selected by overlaying a grid over a map of Toledo in ArcGIS and numbering each grid cell (2 × 2 km). A random number generator was used to identify grid cells for sampling, and we chose a park or garden within each selected cell. We quantified imperviousness (land surfaces that prevent water infiltration) for each site using the percent developed imperviousness layer in the 2011 National Land Cover Dataset54 in ArcMap 10.3. We calculated local imperviousness (300 m radius) and landscape imperviousness (2000 m radius), as scale can be important in appropriately measuring the urban landscape for bees55.

Map displaying site locations in Toledo, Ohio, with reference to the state of Ohio. Base layer coloration indicates percent impervious surface. Darker shades of red represent high impervious surface, and light shades represent low impervious surface. CTmax and CWC were determined for square sites (3 urban, 3 rural). Field measurements body temperature and water content were measured at all 19 sites. This map was created using the 2011 National Landcover Dataset percent developed imperviousness layer54,81 in ArcGIS 10.3.1.

Study Organisms

We focused on the silky striped sweat bee (Agapostemon sericeus), western honeybee (Apis mellifera), and common eastern bumblebee (Bombus impatiens) due to the relative commonness of these species in parks and gardens across Toledo56. In general, sweat bees begin their activity in early to mid-Spring when temperatures reach 14 °C57, while bumblebees and honey bees are known to forage at much lower temperatures58. Most research on thermal tolerance in bees is focused on bumblebees and honeybees, and we included sweat bees because little is known of their physiological tolerances, they are abundant and widely distributed, and they are smaller than the other species. These three species differ in size, foraging preference, sociality, and nest specificity59, increasing the likelihood of detecting differential responses among species.

Field Body Temperature and Water Content

We hand collected sweat bees, honeybees, and bumblebees from a series of 19 sites from June-August 2016 using 120 ml specimen containers (QuickMedical Model#4256). Bees were sampled in the mornings on days with clear skies and temperatures above 22 °C. Upon capture, bees were anesthetized with CO2 to estimate body temperature using a thermocouple (Atkins 351/352) held between the thorax and abdomen for approximately 30 s. Surface temperatures of bees and other insects, at rest, have been found to be similar to internal body temperatures (within 1 °C)60,61. We then transported bees back to the lab in airtight vials (Pelco® Mini Vials) to prevent water loss, and placed the vials in a freezer for 24 hours prior to water content determination. Bee water content was calculated gravimetrically using an analytical balance (Mettler Toledo XPE56) with precision to one microgram. We calculated the water content of each bee as the difference in wet and dry mass divided by wet mass. To calculate dry mass, bees were placed into a drying oven (Thermo Fisher Scientific #151030520) set at 55 °C for at least 48 hours, and then reweighed48. We obtained estimates of water content from all 19 sites, but our temperature measurements are from only 13 sites. We were unable to take body temperature measurements at all 19 sites due to equipment availability.

Thermal and Water Content Limits Sampling

To measure thermal and water content limits, we focused on 6 sites (3 urban, 3 rural) in the metropolitan region of Toledo (Fig. 1), that were selected based on the percent impervious surface within a 300 m radius of the site center (see Fig. 1). Urban sites had an average local impervious surface (300 m) of 57.79% ± 9.6, while rural sites had an average local impervious surface of 23.24% ± 4.5. For each experiment, we collected 15 bees from each site of the same species identified above (five sweat bees, five honeybees, five bumblebees). At each site, we walked a linear transect starting at the site’s center and collected the first five bees of each species we encountered using 120 ml specimen containers. Upon collection, bees were placed in a cooler box without ice (25 °C) to standardize temperatures prior to each experiment, and immediately taken to Bowling Green State University. Bees were given a 1 M sucrose solution upon capture to ensure bee survival during transportation prior to thermal ramping and desiccation trials, which was especially important to ensure survival of honeybees50. All experimental trials began within two hours of collection. The collection period for bees in our thermal and hygric experiments occurred during September 6–22, 2016.

Thermal Tolerance Experiment

We measured critical thermal maximum (CTmax) for each sampled bee with a temperature ramping experiment using an environmental chamber (Memmert HPP 750). The temperature ramp began at 25 °C and increased at a rate of 0.5 °C min−1, following standard methods20. Humidity was held constant at 30%. We used iButton® temperature and humidity data loggers (DS1923) to verify the conditions of the environmental chamber. Bees were placed individually into a 120 ml specimen cup (QuickMedical Model#4256) with a mesh cover that allowed air temperatures within specimen cups to increase with the temperature ramp. Additionally, the mesh top allowed us to easily test the righting response using a puff of air (Giottos AA1900). The loss of righting response indicates an endpoint when muscle functions begin to fail, and is commonly used to estimate CTmax12,13. Bees unable to flip themselves upright within 15 seconds after receiving a puff of air were considered to have lost the righting response. The temperature at which the righting response was lost was recorded as the CTmax, and bees were removed from the environmental chamber after this point. The temperature ramp ended when all 90 bees had reached their CTmax (~2 hrs). All samples were immediately weighed and stored in air-tight vials after the temperature ramp ended. Bees were not given food or water during the temperature ramping period.

Desiccation Tolerance Experiment

We measured critical water content (CWC) by placing a different set of 90 bees in a desiccation cabinet at 0% humidity and a constant temperature of 25 °C (well below CTmax). Humidity was maintained at 0% using Drierite (#60011T), and was verified using an iButton® temperature and humidity logger (DS1923). Bees were placed individually into the same 120 ml specimen cups used in the CTmax experiment and checked on an incremental timescale as follows: (1) every 15 minutes, (2) every 30 minutes, (3) every 1 hour, (4) every 3 hours, (5) every 6 hours, and (6) every 12 hours. We performed three checks of each time period. Each check lasted approximately five minutes, and we tested the bees’ righting response and removed unresponsive bees. Immediately after removal from the desiccation cabinet, bees were placed into pre-weighed Pelco® Minivials for water content determination.

Thermal and Hygric Safety Margins

We calculated thermal and hygric safety margins as measures of the proximity of bees to limits8. Thermal safety margins were calculated as the difference in the measured field body temperature and the 90th percentile CTmax. Hygric safety margins were calculated similarly as the difference in the measured field water content and the 10th percentile CWC. Using 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively, prevented us from using abnormally tolerant individuals to estimate safety margins, while simultaneously preventing negative safety margins (see Mccluney et al. 2017) that might have arisen had we used mean CTmax or CWC values.

Statistical Methods

All statistical tests were conducted in the R statistical environment (version 3.1.3). We used the nlme package62 to fit linear mixed effects models (lme), comparing CTmax and CWC among bee species (A. sericeus, A. mellifera, B. impatiens) and site class (rural, urban), and the interaction effect between species and site class. We included site ID as a random effect to account for inclusion of multiple bees per site. Post-hoc Tukey multiple comparison of means (glht) tests, in the multcomp package63, were used following significant main effects.

Linear mixed effects models were also used to examine relationships between thermal and hygric safety margins and our urbanization metrics (local imperviousness, landscape imperviousness), with site as a random effect to account for inclusion of multiple bees per site. We also used linear mixed effects models to test for relationships between safety margins and bee mass, including site and bee species as random effects. We tested for the significance of fixed effects via likelihood ratio tests with removal of the fixed effect from the model64. Significance was indicated and discussed at α = 0.05 for a test of the core hypotheses, and at α = 0.1 as a threshold for patterns that could be further explored in the future. Assumptions of normality were checked via examination of plots of residuals, and measures of hygric safety margins were logit transformed.

Results

Critical Thermal Maximum (CTmax)

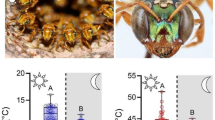

We measured CTmax for 88 bees (30 sweat bees, 30 honeybees, 28 bumblebees). Our measurements varied significantly between species (df = 2, χ2 = 6.56, p = 0.038; Fig. 2A). A post-hoc test revealed that bumblebees had significantly higher CTmax than honeybees and sweat bees, but there was no difference between honeybees and sweat bees. Although we did not detect a significant difference in CTmax between urban and rural sites at α = 0.05 (df = 1, χ2 = 3.84, p = 0.05; S1), a strong trend was apparent in mean CTmax between urban (52.0 °C ± 0.76) and rural sites (49.6 °C ± 1.1). We found no difference in the slope of the relationship between urbanization and CTmax between species (Urbanization x Species: df = 2, χ2 = 0.745, p = 0.69). We also found no significant relationship between CTmax and bee mass (df = 1, χ2 = 2.357, p = 0.125, R2 = 0.02). Bee mass did not differ between urban and rural sites (df = 1, χ2 = 0.488, p = 0.485), but we did find significant differences in mass between species as expected (df = 2, χ2 = 139.8, p < 0.001). Bumblebees had the largest mass (44.97 mg ± 2.81), followed by honeybees (31.39 mg ± 0.46), and sweat bees (4.00 mg ± 0.44).

Differences across bee species for thermal and hygric limits. (A) CTmax was significantly different between species (χ2 = 6.56; p = 0.038), and bumblebees had a higher CTmax than honeybees and sweat bees; (B) CWC was significantly different between all species (χ2 = 77.81; p < 0.001) and sweat bees had the lowest CWC; (C) thermal safety margins were significantly different across all species (χ2 = 55.62; p < 0.001), and honeybees had the largest thermal safety margin; and (D) hygric safety margin was significantly different across all species (χ2 = 97.433; p < 0.001), and sweat bees had the largest hygric safety.

Critical Water Content (CWC)

We measured CWC for a different set of 89 bees (30 sweat bees, 30 honeybees, 29 bumblebees), and our measurements varied significantly between species (df = 2, χ2 = 77.81, p < 0.001; Fig. 2B). A post-hoc multiple comparisons test showed significant differences in CWC between all bee species. Sweat bees had the lowest CWC (highest tolerance), and honeybees the highest CWC (lowest tolerance). However, we did not detect a significant difference in CWC between bees from urban and rural sites (df = 1, χ2 = 3.26, p = 0.071), and we found no interaction between species and urbanization (df = 2, χ2 = 2.44, p = 0.29). We also found no relationship between CWC and bee mass (df = 1, χ2 = 1.94, p = 0.16; R2 < 0.001).

We also found significant differences between species in the length of time they survived in the desiccation cabinet (df = 2, χ2 = 9.87, p = 0.007). A post-hoc multiple comparisons test found sweat bees (39.5 hours ± 8.03) to have longer survival times than honeybees (12.3 hours ± 6.85) (p = 0.005), and statistically similar survival times to bumblebees (19.5 hours ± 2.65) (p = 0.057). We found no differences in survival times between honeybees and bumblebees (p = 0.70). We also found no differences in survival times between bees collected from urban and rural sites (df = 1, χ2 = 0.71, p = 0.40).

Thermal Safety Margin

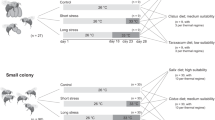

We calculated thermal safety margins for 52 bees (22 bumblebees, 21 honeybees, 9 sweat bees) taken from 13 sites that varied in the amount of impervious surface present around our collection sites (our metric of urbanization) at the local (300 m radius) and landscape (2 km radius) scale. Thermal safety margins declined with increasing impervious surface, but bee species differed in the strength of this response (Table 1). Overall, bumblebees (29.38 °C ± 0.38) had the largest thermal safety margin followed by honeybees (26.95 °C ± 0.37) and sweat bees (24.91 °C ± 0.47). We found thermal safety margin declined with local (300 m) imperviousness for both bumblebees (Fig. 3D) and sweat bees (Fig. 3C), but not for landscape imperviousness. For honeybees, thermal safety margin was not associated with imperviousness at either scale. Overall, we found no relationship between thermal safety margin and bee mass (df = 1, χ2 = 1.93, p = 0.165, R2 = 0.02).

Significant relationships between safety margins (thermal and hygric) and imperviousness (local and landscape) for each bee species. (A) Honeybee hygric safety margin is significantly associated with landscape imperviousness at α = 0.05 (χ2 = 8.847, p = 0.003, R2 = 0.19); (B) Honeybee hygric safety margin is also associated with local imperviousness at the α = 0.1 level (χ2 = 2.81, p = 0.094, R2 = 0.04); (C) Sweat bee thermal safety margin is significantly associated with local imperviousness (χ2 = 6.28, p = 0.012, R2 = 0.49); and (D) Bumblebee thermal safety margin is significantly associated with local imperviousness (χ2 = 4.905, p = 0.027).

Hygric Safety Margin

We calculated hygric safety margins for 88 bees (42 bumblebee, 24 sweat bees, 22 honeybees) taken from 19 sites that varied in the amount of impervious surface present around our collection sites (our metric of urbanization). Hygric safety margin varied interactively with imperviousness and bee species at the landscape level (df = 2, χ2 = 9.014, p = 0.01; Table 1). Sweat bees had the largest hygric safety margin (26.15% ± 1.22), followed by bumblebees (5.25% ± 0.46) and honeybees (2.50% ± 0.45). For honeybees, hygric safety margin declined with landscape imperviousness at α = 0.05 (df = 1, χ2 = 8.847, p = 0.003; Fig. 3A), with a similar trend for local imperviousness at α = 0.1 (df = 1, χ2 = 2.81, p = 0.094; Fig. 3B). For sweat bees and bumblebees, we found no associations between imperviousness and hygric safety margin. Overall, we found no significant relationship between hygric safety margin and bee mass (df = 1, χ2 = 0.06, p = 0.807; R2 < 0.001). Field water content did not differ between urban and rural sites (df = 1, χ2 = −311.34, p = 0.91), but we did find significant differences in field water content between species (df = 2, χ2 = −253.04, p < 0.001). Sweat bees had the lowest field water content (59.3% ± 1.2), followed by bumblebees (65.6% ± 0.4), and honeybees (70.1% ± 0.46).

Discussion

Overall, we found that bee species differ in their thermal limits and water content limits, and their proximity to those limits, with certain species (honeybees) being more susceptible to desiccation than to extreme temperatures. This points out the need to better investigate desiccation, along with temperature, as potential mechanisms underlying the biological effects of global change. We also found that all three species were closer to their physiological limits (either thermal or hygric) with increasing urbanization (local or landscape imperviousness), and that thermal and hygric limits did not vary significantly with urbanization, supporting the “stable limits hypothesis”.

The proximity of honeybees to their water content limits in highly urbanized areas likely represents a high risk for population declines during a drought or heat wave (due to increased water loss rates). However, given that bumblebees and sweat bees were not close to their thermal limits, and that physiological performance often increases as an animal approaches its thermal limits18,65, the increasing proximity to thermal limits for these two species may actually represent a benefit rather than an increased risk. Essentially, warming related to urbanization may benefit bumblebees and sweat bees in cool cities like Toledo, Ohio (<15 days per year above 32 °C), compared to many other US cities. However, we suggest that if increased proximity to thermal limits with urbanization also occurs in warmer cities, urbanization may represent substantial increased risk of population declines in those cities. This hypothesis needs further testing, but is supported by research from a warmer, southeastern US city, Raleigh, NC, USA, where critical thermal maximum (CTmax) was a strong predictor of species presence with increased urbanization15.

Thermal Tolerance

We found no significant differences in CTmax between urban and rural sites. Others have found CTmax to vary with natural temperature gradients, such as elevation13 and latitude66, and multiple studies have identified patterns between CTmax and urbanization15,17,67,68. For example, Diamond17 found differences in CTmax between urban and rural acorn ants, and attributed these differences to evolved plasticity to local environmental conditions. Angilletta68 found urban ants more heat tolerant than rural ants, but were unable to determine whether the differences were attributed to environmental or genetic effects. These studies seem to support the “shifting limits hypothesis”. We hypothesize that bee movement distances may help explain why we found stronger effects on safety margins than limits. Research suggests that bee body size predicts foraging distance69, and the species used in our study are relatively large bees. Greater mobility may prevent local adaptation or even local acclimation, as mobile species encounter both very urbanized and poorly urbanized landscapes, and have greater ability to evade lethal conditions. In addition, any small amount of local adaptation could be erased by genetic mixing. Results might be different for small bees (i.e. Lasioglossum) with short foraging ranges (sensu local adaptation was observed for acorn ants in Diamond17). In addition, results may be different with a larger sample size, or at sites with more extreme levels of impervious surface as others have found when using rural sites with 0% impervious surface17.

We note that bumblebees had higher CTmax than both honeybees and sweat bees, independent of urbanization. Others have found CTmax to increase with bee size13, although the exact mechanism is unclear. We found no significant relationship between bee mass and CTmax, when controlling for species. Furthermore, sweat bees were the smallest bees measured and their CTmax was not significantly different from honeybees. Hamblin et al. found sociality to be an important factor in heat tolerance15, and our results offer some support for the importance of sociality in heat tolerance. Honeybees are eusocial and thermoregulation has been commonly observed in honeybee colonies70,71. While thermoregulation has also been observed for some bumblebee species72,73, we suggest that highly social honeybees may experience less selection pressure for increased CTmax than bumblebees, due to hive thermoregulation.

Desiccation Tolerance

Although little research has been done on critical water content (CWC), the values we collected for bee water content are generally consistent with the reporting of other studies on arthropods32,33,34,40. While CWC values for sweat bees are consistent with the other arthropod taxa mentioned above, honeybees and bumblebees have much higher CWC. Other research has documented particularly high water loss rates in honeybees49, and here we find that they are relatively intolerant of desiccation. It is also interesting to note that honeybees and bumblebees have a tight range of tolerance, suggesting relatively little variation in water content limits in these populations.

Our research suggests key unanswered questions about CWC that future research should investigate. For instance, a better understanding of mechanistic drivers of variation in CWC is needed in general, including for bees. Following earlier work on other arthropods34, we suggest CWC may be associated with functional traits like cuticular hydrocarbon content, physiological stress response pathways, coloration, or other traits, with a variable degree of genetic influence. Moreover, our work suggests there may be a tradeoff between CWC and CTmax (bees were either more sensitive to heat or desiccation). But these ideas are in need of further, more explicit testing.

Thermal and Hygric Safety Margins

We found evidence that all species of bees have decreased safety margins with increasing urbanization. At high impervious sites, bumblebees and sweat bees were both closer to their thermal limit, and honeybees were closer to their hygric limit. These results have several significant implications.

First, many studies have shown that urban areas are able to support diverse bee communities74,75, particularly bumblebees55,76,77. The observed positive effects are typically thought to be due to increased floral resources or nest site availability in urbanized regions56,78,79. However, our research suggests that associations between urbanization and bumblebee thermal physiology could be beneficial or harmful depending on the typical regional temperatures, altering thermal safety margins. Although bees function as facultative endotherms in flight, the body temperatures of flying bees increase with environmental warming25. Populations of both bumblebees and sweat bees may benefit from urbanization in cool regions, because higher ambient temperatures bring bees towards optimal operative temperatures. But these same species may be harmed by urbanization in warmer cities where bees are already near optimal operative temperatures. Likewise, in warm cities, these species may have reduced capacity to tolerate further increases in temperature associated with climate change or heat waves. Efforts to increase green spaces and shade within warm cities could help bees thermoregulate14 and reduce risk. Although we did not investigate CTmin (e.g. cold resistance) in this study, urban warming may lead to higher CTmin values and an overall decrease in thermal tolerance range, a as has been shown in ants17.

Second, we found that honeybees were closer to their hygric limits with increasing urbanization, causing them to be on the edge of their desiccation tolerance. Although bees drink a nectar diet and produce metabolic water, they can regularly become dehydrated in the field25. Water drinking behavior has been observed in honeybees80 and this is consistent with their low desiccation tolerance. Here we also show that honeybees are unable to maintain their water content with increasing urbanization, even in this relatively cool, mesic city. This suggests that metabolic water production may be insufficient to prevent dehydration, in honeybees. Thus, urban gardeners in any city may want to consider providing water sources for honeybees.

Finally, we note that although bumblebee hygric safety margins were not associated with urbanization, bumblebees had narrow hygric safety margins overall. This suggests that bumblebees are able to maintain their water content with increasing urbanization in this cool, mesic city, but urban bumblebees may be at greater risk in drier or hotter cities or during heatwaves or droughts.

Conclusion

Here, we provide the first measurements of bee CWC and one of only a small number examining bee CTmax (only one other in an urban context). Interesting insights emerge from these investigations. First, we found that species differ in their thermal and desiccation tolerance and in their safety margins. Honeybees may be particularly sensitive to desiccation associated with urbanization and climate change, while sweat bees may be more sensitive to temperature changes. More research is needed to determine whether bumblebees are more sensitive to changes in temperature or water balance. This is because, for bumblebees, we found a decline in thermal safety margins, but not hygric safety margins, with urbanization, but overall hygric safety margins were much narrower than their thermal safety margins, indicating potential susceptibility to changes in water balance.

Overall, we argue that a physiological approach provides important information about how bees may respond to changes in climate and land use. Additionally, our research highlights that water balance should not be ignored. Moreover, if changes in bee thermal and water physiology associated with land use or climate change alters bee communities, there could be significant economic consequences related to altered pollination services. Thus, physiological approaches could prove useful in developing strategies to maintain key ecosystem services under climate and land use change.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this study will be made available in supplementary files.

References

Both, C., Bouwhuis, S., Lessells, C. M. & Visser, M. E. Climate change and population declines in a long-distance migratory bird. Nature 441, 81–83 (2006).

Foley, J. A. et al. Global consequences of land use. Science. 309, 570–574 (2005).

Walther, G. R. et al. Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature 416, 389–395 (2002).

Thomas, C. D. et al. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427, 145–148 (2004).

Schweiger, O. et al. Multiple stressors on biotic interactions: How climate change and alien species interact to affect pollination. Biol. Rev. 85, 777–795 (2010).

Kremen, C. et al. Pollination and other ecosystem services produced by mobile organisms: A conceptual framework for the effects of land-use change. Ecol. Lett. 10, 299–314 (2007).

Biesmeijer, J. C. Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science. 313, 351–354 (2006).

Sunday, J. M. et al. Thermal-safety margins and the necessity of thermoregulatory behavior across latitude and elevation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 5610–5615 (2014).

Scaven, V. L. & Rafferty, N. E. Physiological effects of climate warming on flowering plants and insect pollinators and potential consequences for their interactions. Curr. Zool. 59, 418–426 (2013).

Parmesan, C. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 637–669 (2006).

Williams, S. E., Shoo, L. P., Isaac, J. L., Hoffmann, A. A. & Langham, G. Towards an integrated framework for assessing the vulnerability of species to climate change. PLoS Biol. 6, e325 (2008).

Verble-Pearson, R. M., Gifford, M. E. & Yanoviak, S. P. Variation in thermal tolerance of North American ants. J. Therm. Biol. 48, 65–68 (2015).

Oyen, K. J., Giri, S. & Dillon, M. E. Altitudinal variation in bumble bee (Bombus) critical thermal limits. J. Therm. Biol. 59, 52–57 (2016).

Pereboom, J. J. M. & Biesmeijer, J. C. Thermal constraints for stingless bee foragers: The importance of body size and coloration. Oecologia 137, 42–50 (2003).

Hamblin, A. L., Youngsteadt, E., Lopez-Uribe, M. M. & Frank, S. D. Physiological thermal limits predict differential responses of bees to urban heat-island effects. Biol. Lett. 13, 20170125 (2017).

Nguyen, C., Bahar, H., Baker, G. & Andrew, N. R. Thermal tolerance limits of diamondback moth in ramping and plunging assays. PLoS One 9, e87535 (2014).

Diamond, S. E., Chick, L., Perez, A., Strickler, S. A. & Martin, R. A. Rapid evolution of ant thermal tolerance across an urban-rural temperature cline. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 121, 248–257 (2017).

Deutsch, C. A. et al. Impacts of climate warming on terrestrial ectotherms across latitude thermal safety margin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 6668–6672 (2008).

Kellermann, V. et al. Upper thermal limits of Drosophila are linked to species distributions and strongly constrained phylogenetically. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 16228–16233 (2012).

Terblanche, J. S. et al. Ecologically relevant measures of tolerance to potentially lethal temperatures. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3713–3725 (2011).

Huey, R. B. & Stevenson, R. D. Integrating thermal physiology and ecology of ectotherms: A discussion of approaches. Am. Zool. 19, 357–366 (1979).

Araújo, M. B. et al. Heat freezes niche evolution. Ecol. Lett. 16, 1206–1219 (2013).

Gaston, K. J. & Chown, S. L. Elevation and climatic tolerance: A test using dung beetles. Oikos 86, 584–590 (1999).

Baudier, K. M., Amelio, C. L. D., Malhotra, R., Connor, M. P. O. & Donnell, S. O. Extreme insolation: Climatic variation shapes the evolution of thermal tolerance at multiple scales. Am. Nat. 192, 347–359 (2018).

Willmer, P. & Stone, G. Temperature and water relations in desert bees. J. Therm. Biol. 22, 453–465 (1997).

Sinclair, B. J., Addo-Bediako, A. & Chown, S. L. Climatic variability and the evolution of insect freeze tolerance. Biol. Rev. 78, 181–195 (2003).

Hoffmann, A., Hallas, R., Dean, J. & Schiffer, M. Low potential for climate stress adaptation in a rainforest Drosophila species. Science 301, 100–103 (2003).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Sgró, C. M. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470, 479–485 (2011).

Chown, S. L., Sørensen, J. G. & Terblanche, J. S. Water loss in insects: An environmental change perspective. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 1070–1084 (2011).

Addo-Bediako, A., Chown, S. L. & Gaston, K. J. Revisiting water loss in insects: A large scale view. J. Insect Physiol. 47, 1377–1388 (2001).

Block, W. Water or ice? The challenge for invertebrate cold survival. Sci. Prog. 86, 77–101 (2003).

Chen, J., Rashid, T. & Feng, G. A comparative study between Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis richteri on tolerance to heat and desiccation stresses. PLoS One 9, 1–6 (2014).

Gibbs, A. G., Chippindale, A. K. & Rose, M. R. Physiological mechanisms of evolved desiccation resistance in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 200, 1821–1832 (1997).

Hadley, N. F. Water relations of terrestrial arthropods. (Academic Press, 1994).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Parsons, P. A. Selection for increased desiccation resistance in Drosophila melanogaster: additive genetic control and correlated responses for other stresses. Genetics 122, 837–845 (1989).

Weldon, C. W., Nyamukondiwa, C., Karsten, M., Chown, S. L. & Terblanche, J. S. Geographic variation and plasticity in climate stress resistance among southern African populations of Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Sci. Rep. 8, 1–13 (2018).

Terblanche, J. S. & Kleynhans, E. Phenotypic plasticity of desiccation resistance in Glossina puparia: Are there ecotype constraints on acclimation responses? J. Evol. Biol. 22, 1636–1648 (2009).

McCluney, K. E. Implications of animal water balance for terrestrial food webs. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 23, 13–21 (2017).

Markow, T. A., Matzkin, L. M. & Watts, T. D. Desiccation resistance in four Drosophila species: Sex and population effects. Fly (Austin) 1, 268–273 (2007).

Schilman, P. E., Lighton, J. R. B. & Holway, D. A. Water balance in the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) compared with five common native ant species from southern California. Physiol. Entomol. 32, 1–7 (2007).

Youngsteadt, E., Dale, A. G., Terando, A. J., Dunn, R. R. & Frank, S. D. Do cities simulate climate change? A comparison of herbivore response to urban and global warming. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 97–105 (2015).

Gaffin, S. R. et al. Variations in New York City’s urban heat island strength over time and space. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 94, 1–11 (2008).

Imhoff, M. L., Zhang, P., Wolfe, R. E. & Bounoua, L. Remote sensing of the urban heat island effect across biomes in the continental USA. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 504–513 (2010).

Yuan, F. & Bauer, M. E. Comparison of impervious surface area and normalized difference vegetation index as indicators of surface urban heat island effects in Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 106, 375–386 (2007).

Schueler, T. R. The importance of imperviousness. Watershed Prot. Tech. 1, 100–111 (1994).

Shuster, W. D., Bonta, J., Thurston, H., Warnemuende, E. & Smith, D. R. Impacts of impervious surface on watershed hydrology: A review. Urban Water J. 2, 263–275 (2005).

Groffman, P. M. et al. Ecological homogenization of urban USA. Front. Ecol. Environ. 12, 74–81 (2014).

McCluney, K. E., Burdine, J. D. & Frank, S. D. Variation in arthropod hydration across US cities with distinct climate. J. Urban Ecol. 3, 1–9 (2017).

Atmowidjojo, A. H., Wheeler, D. E., Erickson, E. H. & Cohen, A. C. Temperature tolerance and water balance in feral and domestic honey bees, Apis mellifera L. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 118A, 1399–1403 (1997).

Kovac, H., Kafer, H., Stabentheiner, A. & Costa, C. Metabolism and upper thermal limits of Apis mellifera carnica and A. m. ligustica. Apidologie 45, 664–677 (2014).

Dale, A. G. & Frank, S. D. Urban plants and climate drive unique arthropod interactions with unpredictable consequences. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 29, 27–33 (2018).

Schmidlin, T. W. The urban heat island at Toledo, Ohio. Ohio J. Sci. 89, 38–41 (1989).

Burdine, J. D. & Taylor, D. E. Neighbourhood characteristics and urban gardens in the Toledo metropolitan area: staffing and voluntarism, food production, infrastructure, and sustainability practices. Local Environ. 23, 198–219 (2017).

Homer, C. G. et al. Completion of the 2011 National Land Cover Database for the conterminous United States - Representing a decade of land cover change information. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sensing 81, 345–354 (2015).

Glaum, P., Simao, M., Vaidya, C., Fitch, G. & Iulinao, B. Big city Bombus: using natural history and land-use history to find significant environmental drivers in bumble-bee declines in urban development. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 170156 (2017).

Pardee, G. L. & Philpott, S. M. Native plants are the bee’s knees: local and landscape predictors of bee richness and abundance in backyard gardens. Urban Ecosyst. 17, 641–659 (2014).

Richards, M. H. & Packer, L. Annual variation in survival and reproduction of the primitively eusocial sweat bee Halictus ligatus (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). Can. J. Zool. 73, 933–941 (1995).

Goulson, D. Effects of introduced bees on native ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 1–26 (2003).

Michener, C. D. The bees of the world. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

Casey, T. M. Activity patterns, body temperature and thermal ecology in two desert caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Ecology 57, 485–497 (1976).

Stabentheiner, A. & Schmaranzer, S. Thermographic determination of body temperatures in honey bees and hornets, calibration and applications. Thermology 2, 563–572 (1987).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S. & Sarkar, D. R Core Team (2014) nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models 1–117 (2014).

Hothorn, T., Bretz, F. & Horthorn, M. The multcomp package (2009).

Bolker, B. M. et al. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 127–135 (2009).

Angilletta, M. J. Thermal adaptation: a theoretical and empirical synthesis. (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Kerr, J. T. et al. Climate change impacts on bumblebees converge across continents. Science. 349, 177–180 (2015).

Brans, K. I. et al. The heat is on: genetic adaptation to urbanization mediated by thermal tolerance and body size. Glob. Chang. Biol. 1–10 (2017).

Angilletta, M. J. et al. Urban physiology: City ants possess high heat tolerance. PLoS One 2, e258 (2007).

Greenleaf, S. S., Williams, N. M., Winfree, R. & Kremen, C. Bee foraging ranges and their relationship to body size. Oecologia 153, 589–596 (2007).

Cooper, P. D., Schaffer, W. M. & Buchmann, S. L. Temperature regulation of honey bees (Apis mellifera) foraging in the Sonoran Desert. J. Exp. Biol. 114, 1–15 (1985).

Heinrich, B. Mechanisms of body-temperature regulation in honeybees, Apis mellifera. II. Regulation of thoracic temperature at high air temperatures. J. Exp. Biol. 85, 73–87 (1980).

Heinrich, B. & Heinrich, M. J. E. Size and caste in temperature regulation by bumblebees. Physiol. Zool. 56, 552–562 (1983).

Heinrich, B. Temperature regulation in the bumblebee Bombus vagans: A field study. Science. 4018, 185–187 (1972).

Hall, D. et al. The city as a refuge for insect pollinators. Conserv. Biol. 31, 24–29 (2017).

Matteson, K. C., Ascher, J. S. & Langellotto, G. A. Bee richness and abundance in New York City urban gardens. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 101, 140–150 (2008).

Winfree, R., Williams, N. M., Dushoff, J. & Kremen, C. Native bees provide insurance against ongoing honey bee losses. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1105–1113 (2007).

McFrederick, Q. S. & LeBuhn, G. Are urban parks refuges for bumble bees Bombus spp. (Hymenoptera: Apidae)? Biol. Conserv. 129, 372–382 (2006).

Bates, A. J. et al. Changing bee and hoverfly pollinator assemblages along an urban-rural gradient. PLoS One 6, e23459 (2011).

Hennig, E. I. & Ghazoul, J. Pollinating animals in the urban environment. Urban Ecosyst. 15, 149–166 (2012).

Visscher, P. K., Crailsheim, K. & Sherman, G. How do honey bees (Apis mellifera) fuel their water foraging flights? J. Insect Physiol. 42, 1089–1094 (1996).

Xian, G. et al. Change of impervious surface area between 2001 and 2006 in the conterminous United States. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sensing 77, 754–762 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Toledo City Parks, Wood County Parks, Olander Parks, Toledo Botanical Gardens, and the Toledo Zoo for allowing us to use their properties as collection sites. These organizations were hospitable and provided information that aided in site selection. Edward Lagucki and Erin Plummer assisted in the experimental trials, and helped with measurements of bee water content. We would also like to thank Shannon Pelini, Helen Michaels, Andrew Gregory, and the editor and anonymous reviewers, for comments and suggestions that improved the manuscript. BGSU provided funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. Burdine designed and performed all experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. K.E. McCluney contributed at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burdine, J.D., McCluney, K.E. Differential sensitivity of bees to urbanization-driven changes in body temperature and water content. Sci Rep 9, 1643 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38338-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38338-0

This article is cited by

-

Heat and desiccation tolerances predict bee abundance under climate change

Nature (2024)

-

Urbanisation impacts the diversity, coloration, and body size of wild bees in a Mediterranean city

Regional Environmental Change (2024)

-

Deforestation narrows pollen diet diversity of generalist orchid bees

Journal of Insect Conservation (2024)

-

Low heat tolerance and high desiccation resistance in nocturnal bees and the implications for nocturnal pollination under climate change

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Bee functional groups respond to vegetation cover and landscape diversity in a Brazilian metropolis

Landscape Ecology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.