Abstract

Concomitant complementary medicine (CM) and conventional medicine use is frequent and carries potential risks. Yet, CM users frequently neglect to disclose CM use to medical providers. Our systematic review examines rates of and reasons for CM use disclosure to medical providers. Observational studies published 2003–2016 were searched (AMED, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO). Eighty-six papers reporting disclosure rates and/or reasons for disclosure/non-disclosure of CM use to medical providers were reviewed. Fourteen were selected for meta-analysis of disclosure rates of biologically-based CM. Overall disclosure rates varied (7–80%). Meta-analysis revealed a 33% disclosure rate (95%CI: 24% to 43%) for biologically-based CM. Reasons for non-disclosure included lack of inquiry from medical providers, fear of provider disapproval, perception of disclosure as unimportant, belief providers lacked CM knowledge, lacking time, and belief CM was safe. Reasons for disclosure included inquiry from medical providers, belief providers would support CM use, belief disclosure was important for safety, and belief providers would give advice about CM. Disclosure appears to be influenced by the nature of patient-provider communication. However, inconsistent definitions of CM and lack of a standard measure for disclosure created substantial heterogeneity between studies. Disclosure of CM use to medical providers must be encouraged for safe, effective patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health care seeking invariably involves choices regarding the use of what can often be many competing health care services, treatments and providers from both within and beyond the public health care system. This level of individual choice in health seeking is increasingly recognised with person-centred care being given predilection as a favourable model of care provision in public health1,2, situating individuals as active participants at the centre of their health management. Patient autonomy and preference are important features of person-centred care2 to be considered by medical providers alongside safety and treatment outcomes in their patient management.

Amidst this context, complementary medicine (CM) - a broad, varied field of health care practices and products customarily excluded from conventional medical practice and dominant health care systems3 – is often the focus of relatively hidden patient health seeking yet is making its presence felt in primary care, chronic disease management and other areas4. Despite appreciable gaps in evidence of effectiveness5, CM use remains prevalent amongst the general population6. While there is controversy amongst medical providers around the role and value of CM7, the vast majority of CM use is concurrent to conventional medicine8 with CM users visiting a GP more frequently than non-CM users9.

Serious adverse effects and harm from CM appear relatively rare but substantial associated direct and indirect risks remain10,11, particularly regarding ingestive biologically-based CM (such as herbal medicines or supplements)12,13,14, which may be obtained from unreliable sources, self-prescribed or consumed without professional supervision11,15. Exacerbating such risks is an absence of both awareness of concurrent CM and conventional medicine use, and of procedures ensuring appropriate oversight of concurrent use11. Furthermore, patients often approach CM as inherently safe and may not perceive a need to communicate their CM use to medical providers16,17. Addressing the risks associated with concurrent use is the responsibility of both patients and their medical providers18, and arguably essential for general practitioners in their capacity as primary care gatekeepers19.

A previous review of the literature pertaining to CM use disclosure to medical providers published in 2004 identified twelve papers published between 1997–2002 reporting a CM disclosure rate of 23–90% alongside key factors - patient concern about possible negative response from their medical provider, patient perception that the medical provider was not sufficiently knowledgeable in CM and therefore unable to contribute useful information, and the absence of medical provider inquiry about the patient’s CM use – fuelling non-disclosure20. Disclosure has been increasingly identified as a central challenge facing patient management amidst concurrent use over the last 13 years21,22 but no systematic review or meta-analysis has been conducted on this topic over this recent period.

In direct response, this paper provides an update to the previous review, assessing research findings regarding CM use disclosure to medical providers since 2003. Our review employs a qualitative synthesis to explore disclosure rates, patient attitudes to disclosure, reasons for disclosing and not disclosing, and the role of patient-provider communication in disclosure. In addition, to gain further insight into the extent of this important health services issue across settings, we undertook a meta-analysis of disclosure rates among patients using ingestive biologically-based CM.

Methods

A review protocol was developed in accordance with the PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) 2015 checklist23 and MOOSE (Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (see Supplementary Methods S1)24. We developed the protocol for the systematic review before initiating the literature search. The protocol was not registered on a systematic review protocol database. The strategy for the meta-analysis was developed after all articles had been selected for the systematic review based upon the trend we observed in the rates of disclosure among individuals using biologically-based CM products. Prior to initiating the meta-analysis the protocol was modified to define the statistical methods we would employ for the quantitative synthesis. The final manuscript was prepared in accordance with AMSTAR guidelines25 where appropriate with respect to the observational nature of the review aim.

Review aim

This review aims to describe the prevalence and characteristics of disclosure of CM use to medical providers.

Search strategy

The search strategy was informed by the review published by Robinson & McGrail20. A search was conducted on 13–14 February 2017 on the EBSCOhost platform of the following databases: AMED, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. Three search strings were combined to identify studies which assessed the use of CM, patient-provider communication, and conventional medicine clinical settings. CM search terms were chosen on the basis of CM modalities identified as common in use among the general population in recent literature26. Truncation symbols were applied where appropriate to capture related terms. The full search string was as follows: S1 (complementary medicine OR complementary therap* OR alternative medicine OR alternative therap* OR natural medicine OR natural therap* OR acupunctur* OR aromatherap* OR ayurved* OR chiropract* OR herbal* OR phytotherap* OR homeopath* OR hypnosis OR hypnotherap* OR massage OR naturopath* OR nutrition* OR diet therap* OR vitamin therap* OR supplement OR osteopath* OR reflexology* OR traditional Chinese medicine OR yoga) AND S2 (disclos* OR communicat* OR patient use OR reasons for use OR discuss*) AND S3 (medical practi* OR general practi* OR health care provider OR primary care provider OR physician). The full search strategy is outlined in Table 1.

In order to provide an update on the review by Robinson & McGrail20, a date range of January 2003 to December 2016 was set. The reference and bibliographic lists of all studies included in the review were searched to minimise the likelihood of missed citations. In addition, any systematic reviews identified during the literature search which presented data on topics related to the primary research aim were also searched manually. The authors contributed their own content expertise in clinical practice, health services research and primary care to ensure important known articles were not overlooked.

Selection criteria

Our review included cross-sectional data from observational studies as this research design was deemed the most appropriate for determining prevalence of health behaviours, determinants and outcomes27. All observational study designs constituting original, peer-reviewed research were considered for the qualitative synthesis if they reported on rates of, or reasons for, disclosure/non-disclosure of CM use to conventional medicine providers by a broad range of members from the general population. CM use was defined as the use of any practice or product falling outside of those considered part of conventional medicine28, whether administered as self-treatment or by a CM practitioner. We excluded experimental study designs, which may have impacted on natural communication patterns between patients and providers, alongside studies assessing specific populations which could not reasonably be considered to represent a broad range of individuals (e.g. disease-specific populations). Studies were not excluded on the basis of language.

During selection of studies for meta-analysis, additional criteria were applied with respect to homogeneity, in order to ensure the central estimate of disclosure frequency would provide external validity. This additional criteria required that participants were adults, the study reported a true and well-defined rate of disclosure occurring within the previous twelve months, and involved participants who used biologically-based CM (herbs/plant-based medicines, vitamins, minerals and other oral supplements). Of those papers reporting studies sharing a common data source (e.g. if multiple papers reported on data from the same survey study), we included only one of those publications in order not to artificially inflate our sample size. In such cases, the risk of bias was evaluated for all such publications and only included that publication deemed to have the lowest risk of bias.

Study selection

Citations were exported into EndNote X8 (Clarivate Analytics 2017) reference management software for assessment. Following removal of duplicates, the initial citations were screened against inclusion/exclusion criteria by title and abstract. Review and commentary articles were set aside for a manual search of their included studies. Remaining citations were screened by full-text perusal and those found to adhere to all selection criteria were selected for review. The reference lists of the selected studies were manually searched for additional articles. Full review of all eligible citations was conducted by the lead author (HF). A selected sample of eligible studies (10%) were reviewed at each stage of screening by a second reviewer (AS), as were any studies under question, and discrepancies were addressed through discussion until consensus was reached. The justification for excluding articles following screening the full text was recorded.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Papers selected for review were re-read thoroughly with data extracted into pre-prepared tables outlining study characteristics, outcomes of interest (disclosure/non-disclosure rates and reasons) and parameters of those outcomes (CM type disclosed, how disclosure was defined). Further to this, papers were read in full-text once more to identify other notable findings relating to disclosure, which were categorised and tabulated heuristically. The template for data extraction was drafted during the pre-review protocol development phase with agreement from all authors. Data extraction was conducted by one reviewer (HF) with a selected sample (10% alongside any data under question) checked by another reviewer (AS). Any discrepancies were addressed through discussion until consensus was reached.

The resulting tables were examined to identify studies meeting the criteria for meta-analysis. These identified studies were subjected to risk of bias assessment using Hoy et al.’s tool for prevalence studies, which assesses ten items across four domains (sample selection, non-response bias, measurement bias, analysis bias) alongside a summary score29. Studies identified as high risk of bias were excluded from the final selection for meta-analysis. Risk of bias was considered high if four or more items were not adequately addressed, if the first three items indicated an unacceptable level of sampling bias, or if item ten was not adequately addressed as this item affected calculation of disclosure rates.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Due to the expected heterogeneity of each study’s parameters of disclosure, no average disclosure rate was calculated for the full review; instead a meta-analysis was conducted on those studies demonstrating sufficient homogeneity in study design and a low risk of bias. The principal summary measure used for meta-analysis was disclosure rate of CM use to medical providers. Meta-analysis was conducted using events (number of disclosers) and subset of sample size (number of CM users) to determine event rates of disclosure. Where studies reported disclosure rates only as percentages, events were calculated using figures for the number of participants who responded to the disclosure question. Where these figures were unavailable, the study was considered to fail to address item 10 on the risk of bias assessment tool and was excluded from meta-analysis.

Statistical heterogeneity between studies was explored using I2 and chi-square statistics. I2 values greater than 25%, greater than 50%, and greater than 75% indicate moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively30. Due to the relatively low power of this test, a P value of 0.10 or less from the chi-square test was regarded to indicate significant heterogeneity30. Analysis was completed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V3 software (Biostat Inc. 2017).

Results

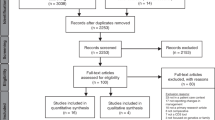

From an initial 5,071 non-duplicate citations, eighty-six studies were selected for review. The reasons for exclusion at full-text screening are provided in Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment

Twenty studies met the initial inclusion criteria for meta-analysis and were subjected to assessment of reporting quality and risk of bias using Hoy et al.’s tool for prevalence studies29. Collectively, studies performed poorly across most domains relating to external validity, either due to poor methodological conduct or inadequate reporting on methods relating to target population (item 1), random selection (item 3) and response bias (item 4). However, sampling frame representation was well conducted and reported (item 2). Domains relating to internal validity were addressed well, with the exception of instrument validity (item 7).

Of the twenty studies, four were found to exhibit a high risk of bias due to poorly defined parameters for disclosure rate definition or analysis31,32,33,34 and were consequently excluded from meta-analysis. The remaining sixty-six studies which did not meet the initial inclusion criteria for meta-analysis represented a heterogeneous range of study designs in which disclosure was not reported as a primary outcome, but as a secondary outcome or qualitative finding, and thus the resulting data underwent narrative synthesis without risk of bias appraisal. Table 3 displays full details of risk of bias assessment.

Study characteristics

Of the eighty-six studies reviewed, seventy-nine provided quantitative data31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110, three qualitative data111,112,113, and four mixed-method data34,114,115,116 relevant to CM disclosure rates and/or reasons for disclosure/non-disclosure (selection process summarised in Fig. 1). Nine studies were excluded following review of the full text. A vast majority of the selected studies (n = 83) used a cross-sectional survey design31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,114,115,116, two employed a multistage qualitative approach111,112, and one an ethnographic interview design113. While the final selection of research spanned twenty countries, just under half of the studies (n = 40) were conducted in the United States (US)31,32,33,34,35,37,40,41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,56,57,60,76,79,80,87,88,89,90,91,94,100,101,105,107,108,112,113,114. Settings were diverse with data collection occurring primarily in general practice or hospital clinics34,35,36,37,38,41,43,55,58,61,62,63,64,66,68,69,74,76,77,78,79,81,82,86,87,92,97,98,101,103,106,107,109,111,112,114,115,116, face-to-face in participants’ households33,39,46,47,48,49,50,52,53,54,67,70,72,84,85,88,89,90,91,93,94,100,102,104, or by telephone and/or mail31,40,45,51,56,57,59,65,73,75,95,96,108,110. Less common settings included CM clinics34,42,68, retail outlets60,71,99,105, community meal sites44,113, seminars78,80, and online platforms32,83.

While some samples consisted entirely of CM users45,50,51,54,83,89,98, most involved a subset of CM users within a larger sample. Full samples ranged from 35 to 34,525 with an average of 4,144. Amongst those studies reporting figures for the subset of CM users, samples ranged from 28 to 16,784 with an average of 1,268 and a total of 101,417. Participants were predominantly adults with a small number of studies focussed on older adults44,57,65,94,95,105,110,113,114, children45,58,63,68,73,97,103,106,115,116, adolescents41,97, or all age groups61,99,112. More than half of the studies included users of various types of CM (n = 45)31,35,36,38,41,42,43,50,51,54,57,58,59,61,62,63,65,66,68,72,73,75,76,80,81,82,85,88,89,96,97,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,115,116, while others were limited to users of specific types of CM such as herbs and/or supplements32,33,34,37,44,45,46,47,52,53,55,56,60,64,67,69,70,71,74,77,78,79,83,86,87,92,93,94,95,98,99,100,101,109,114, yoga48,91, tai chi49,90, mind-body medicine40, practitioner-provided CM39, or local traditional medicine84.

Almost half of the selected studies (n = 40) used a convenience sampling method32,34,35,36,37,41,42,43,44,55,58,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,69,74,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,86,87,92,97,101,103,106,107,109,111,114,115,116. However, twenty-two studies used a nationally representative sample31,39,40,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,59,73,85,89,90,91,94,96,100,110, while others applied some method of probability randomisation38,56,65,75,84,88,99, stratification33,45,57,67,70,72,93,108, weighting71,104,113, or purposiveness95,98,102,105,112 during sampling. Table 4 provides full details of the study characteristics identified from the reviewed literature.

Following risk of bias assessment, sixteen studies were considered suitable for meta-analysis of CM disclosure rates. Two were excluded from analysis46,52 on the basis that they used data from an earlier version of the same national survey as reported in another included manuscript54. Studies selected for meta-analysis represented a wide geographical spread including North America35,54,87, Central America88, Continental Europe69,77,82, the United Kingdom39, the Middle East38,67,85, West Africa84, and Asia62,81. Sample sizes included in the meta-analysis ranged from 35 to 7,493 with an average of 840 and a total of 11,754 CM users. Papers excluded due to a high risk of reporting bias represented an additional 3,222 CM users.

Prevalence and parameters of disclosure

Rates of disclosure varied substantially across studies, ranging from 7%114 to 80%40. Studies including biologically-based CM fell within a range of 7%114 to 77%44, while the highest rate of disclosure (80%) was reported by researchers assessing the use of mind-body medicine exclusively40. Parameters used for defining and measuring disclosure also varied, with the most common parameters outlined as participant disclosure of their use of CM within the last twelve months to a medical provider (n = 30)31,32,33,36,38,40,45,46,47,48,49,50,52,54,57,62,65,67,68,70,71,73,81,82,84,85,87,88,95,100,115,116. Others studies examined participants’ disclosure to a medical provider of their current CM use35,74,77,78,79,83,98,109,111, use within the last month34,53,69,86, use within the last 24 months50,51, had always/usually/sometimes/never disclosed39,59,60,66,72,110, had ever discussed their CM use with a conventional provider37,43,64,75,76, had partially or fully disclosed their CM use56,114, had disclosed when asked41, had discussed before use92, reported rates of disclosure per episode of use89, or how the patient felt about disclosing80,112. A number of papers did not explicitly define their parameters for measuring disclosure42,44,55,58,61,63,90,91,93,94,96,97,99,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,113.

The outcomes of the meta-analysis of the rate of disclosure of CM use by individuals using biologically-based CM is presented in Fig. 2. The measure of central tendency provided an overall disclosure rate of 33% (95% CI 24·1% to 42·8%, I2 = 98·6%). Between the fourteen included studies, the lowest reported disclosure rate was 12% and the highest was 59%. Heterogeneity was assessed across the fourteen samples (Q-value 904.955, p < 0.001, I2 = 98.563). Although homogeneity was affected by the substantially larger sample size in Jou et al.’s 2016 study54, the paper was not excluded as it used a strong, internationally recognised dataset with very low risk of bias. The employment of a random effects model accounted for the impact of this study on homogeneity and its inclusion was not found to impact significantly on the measure of consistency within this model.

Reasons for non-disclosure and disclosure

Twenty-five studies reported participant reasons for non-disclosure36,37,42,54,55,56,57,59,67,76,77,78,79,83,84,85,90,92,98,105,107,110,111,112,113, and four reported reasons for disclosure of CM use to medical providers56,111,112,113. The most commonly cited reasons patients gave for non-disclosure were fear of the provider’s disapproval36,42,54,55,56,67,76,77,78,83,84,85,90,92,105,107,110,111,112,113, followed by the provider not asking37,42,54,55,56,57,59,67,76,77,78,83,84,90,98,110,111,112,113, the patient perceiving disclosure as unimportant42,54,55,56,57,59,67,76,78,79,84,85,90,92,98,105,107,110, belief the physician would not have relevant knowledge of CM36,42,54,56,67,76,77,78,107,113, lack of time during consultation or forgetting36,42,54,56,57,76,78,92,105, belief that CM was safe and would not interfere with conventional treatment42,78,83,85,111, the patient not using CM regularly or at the time of consulting with the conventional provider54,78,83,85, and previous experiences of a negative response from conventional providers54,84,90,112. The most commonly cited reason for disclosure was that the provider asked about CM use56,111,112, followed by the patient expecting the provider to be supportive of their CM use112,113, believing disclosure was important for safety56,113, belief the provider would have relevant knowledge or advice about CM56, and belief that disclosing CM use may help other patients with the same condition56. Full details of reasons are shown in Table 5.

When participants were asked whether they thought disclosure was important, more than 67% agreed it was36,63,68,80,110. This percentage was highest (93%) among participants who were surveyed in CM clinics68, which was consistent with other studies reporting higher disclosure rates among users of practitioner-provided CM compared with self-administered CM50,51,81,89. Conversely, one study found lower disclosure rates among those using practitioner-provided CM, specifically where participants were consulting a CM practitioner and a medical provider for the same condition65.

Impact of provider response on decisions to disclose

In a qualitative analysis, Shelley et al. found patients’ perceptions of how their medical provider might respond to their CM use was an important factor in the decision of whether or not to disclose112. A perception of the medical provider as accepting and non-judgemental encouraged disclosure while fear of a negative response from their medical provider led to non-disclosure112. One paper reported 59% of participants wanted to discuss CM with their medical provider (despite only 49% having done so), and 37% of non-disclosers wished it were easier to have such discussions35. In another study, the percentage of participants who wanted to discuss CM with their provider represented a substantial majority at 82% (despite only 60% having done so)61.

When the actual response of the provider to disclosure of CM use was explored by researchers, negative or discouraging responses were reported by a minority of respondents representing less than 20% of disclosers65,71,77,85,105, or were not reported at all111. However, in five papers positive or encouraging responses to disclosure of CM use by a medical doctor were reported by a substantial proportion of respondents representing 32–91% of disclosers63,65,77,79,85,105. Neutral responses from medical providers were also common, reported by 8–32% of disclosers in three studies77,85,111.

Discussion

This review and meta-analysis provides a detailed overview and update of CM use disclosure to medical providers. Regarding the update to the 2004 paper20 afforded by this review, a substantially larger volume of literature reporting on CM disclosure was identified in our search, suggesting an increase in researcher interest in this aspect of patient-provider communication. Our analysis reveals little discernible improvement to disclosure rates over the last thirteen years. Consistent with the findings of the previous review, we found reports of disclosure vary widely. However, our additional meta-analysis on selected papers shows approximately two in three CM users do not disclose their CM use to medical providers. In view of the potential risks associated with unmanaged concomitant use of conventional and complementary medicine11,14, the value of increasing this rate of disclosure is accentuated.

Furthermore, our narrative review identified three distinct yet interrelated findings relating to patient-practitioner communication. Firstly, disclosure of CM use to medical providers is influenced by the nature of providers’ communication style; secondly, perceived provider knowledge of CM use is a barrier to discussions of CM use in clinical consultation; and thirdly, such discussions and subsequent disclosure of CM use may be facilitated by direct inquiry about CM use by providers. We consider this in the context of contemporary person-centred health care models.

Communication style was a repeated factor affecting disclosure rates in this review; disclosure of CM use was found to be encouraged by patient perceptions of acceptance and non-judgement from medical providers112, and inhibited by patient fears or previous experiences of discouraging responses from providers36,42,54,55,56,67,76,77,78,83,84,85,90,92,105,107,110,111,112,113. In practice, negative responses from medical providers appear to represent a deviation from the more commonly positive or neutral responses noted by participants of the reviewed studies as well as others117,118. However, such fears and subsequent non-disclosure of CM use could potentially be addressed by medical providers through communication with patients about CM in a direct, supportive, non-judgemental manner to build trust and communicative success119.

The reviewed literature shows patient perceptions of medical providers as lacking relevant knowledge about CM is a notable reason for non-disclosure. While examination of provider attitudes was not within the scope of this review, three reviewed papers included an assessment of medical providers’ attitudes toward discussing CM and identified lack of CM knowledge as a cause of providers’ reluctance to initiate such discussions76,111,112. Providers’ own perceived lack of CM knowledge as an obstacle to patient-provider CM communication also reflects other research examining provider perspectives on CM120,121. While the inclusion of CM in medical school curricula does occur in some countries (e.g. the US122, Canada123, UK124, Germany125, and Switzerland126), and is of interest to medical students127,128, this level of CM learning appears insufficient to equip medical providers with the confidence to address patient CM queries120,121. Furthermore, the depth and scope of CM knowledge to be realistically encouraged amongst medical providers has been contested124,125 and may be best facilitated on a case by case basis taking into account the circumstances of both provider and patient involved. Ideally, regardless of the level of CM knowledge held, the medical provider should strive to facilitate overall coordination and continuity of care for patients covering all treatments and providers, including those of CM.

Our analyses suggest there may be a vital role for medical providers in facilitating patient preference by enquiring with patients about CM in order to help improve disclosure rates. Other studies show discussions in conventional medical settings about CM use are more commonly patient rather than provider initiated118,129, a pattern reflected in the findings of some papers in this review35,68,76. This pattern suggests provider initiation of such discussions may be an avenue for improving disclosure rates, which may be achieved by means such as standard inclusion of CM use inquiry in case-taking education for medical students, as is currently the case in Switzerland130. Indeed, examination of the impact on disclosure rates of specific questions related to dietary supplements found medical providers’ questioning more than doubled the rate of supplement use disclosure131. This communicative success may be facilitated through employment of person-centred approaches to clinical care, which encompass patient involvement in shared decision-making, provider empathy and recognition of patients’ values119, encouraging a shared responsibility for communication and subsequent discussion of CM use.

While this review provides insight which could be integral to improving patient care during concomitant use of CM and conventional medicine, it also reveals the complexities of patient-practitioner communication in contemporary clinical settings. Further research into the nature of prevailing communication patterns, including differences in disclosure behaviours between populations of different demographics, is needed. As research into disclosure becomes more nuanced and data collection more consistent (e.g. through development and use of standardised instruments), future research could examine changes in patterns of and influences on disclosure. Additionally, research exploring the relationship between communication and treatment outcomes is warranted to provide a richer, deeper understanding of the impact of patient care dynamics. Such understanding could arguably provide the scaffolding for robust, effective, efficient public health policy and practice guidelines.

Limitations of this review

The findings from our review need to be considered within the context of certain limitations. The varied nature and lack of a consistent international definition of CM lend a high degree of heterogeneity to the collection of studies appraised132. Likewise, while the wide variation in disclosure rates is likely to be partially due to confounding factors relating to differences among target populations (e.g. age, gender), settings (e.g. hospital, community clinics), geographical location (e.g. country/region), and sample sizes, the absence of a standard, validated tool for measuring disclosure also impacts the analysis and reporting on disclosure rates. The heterogeneity produced by these limitations reduced the number of papers suitable for meta-analysis and prevented a more robust, fixed-model meta-analysis on this topic, as well as prohibiting meta-analyses of CM categories other than biologically-based CM due to insufficient data. Additionally, identifying a comprehensive selection of studies to review was difficult due to disclosure frequently being reported as a secondary outcome and thus not being mentioned in the paper’s title, abstract or keywords. However, these limitations have been minimised where possible by following systematic review best practice, and while remaining mindful of the limitations of our review, the importance of the findings presented here for contemporary healthcare practice and provision should not be underestimated.

Conclusion

The rate of disclosure regarding CM use to medical providers remains low and it appears that disclosure is still a major challenge facing health care providers. This review, alongside previous research, suggests that patient decision-making regarding disclosure and non-disclosure of CM use to a medical provider is impacted by the nature of patient-provider communication during consultation and perceptions of provider knowledge of CM. The initiation of conversations about CM with patients and provision of consultations characterised by person-centred, collaborative communication by medical providers may contribute towards increased disclosure rates and mitigate against the potential direct and indirect risks of un-coordinated concurrent CM and conventional medical care. This is a topic which should be treated with gravity; it is central to wider patient management and care in contemporary clinical settings, particularly for primary care providers acting as gatekeeper in their patients’ care.

References

Coalition for Collaborative Care. Personalised Care and Aupport Planning Handbook: The Journey to Person-centred Care (Core Information). (ed NHS England) (Medical Directorate, Leeds, 2016).

World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. (WHO Press, Geneva, 2015).

World Health Organization. Traditional, complementary and integrative medicine: About us, https://www.who.int/traditional-complementary-integrative-medicine/about/en/ (2018).

Ben-Arye, E., Frenkel, M., Klein, A. & Scharf, M. Attitudes toward integration of complementary and alternative medicine in primary care: perspectives of patients, physicians and complementary practitioners. Patient Educ. Couns. 70, 395–402 (2008).

Fonnebo, V. et al. Researching complementary and alternative treatments – the gatekeepers are not at home. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 7, 7, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-7-7 (2007).

Harris, P., Cooper, K., Relton, C. & Thomas, K. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: a systematic review and update. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 66, 924–939 (2012).

Wahner-Roedler, D. L. et al. Physicians’ attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine and their knowledge of specific therapies: 8-Year follow-up at an academic medical center. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 20, 54–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.09.003 (2014).

NCCIH. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name?, https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health (2016).

Reid, R., Steel, A., Wardle, J., Trubody, A. & Adams, J. Complementary medicine use by the Australian population: a critical mixed studies systematic review of utilisation, perceptions and factors associated with use. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 16, 176 (2016).

White, A. et al. Reducing the risk of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): challenges and priorities. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 6, 404–408 (2014).

Wardle, J. L. & Adams, J. Indirect and non-health risks associated with complementary and alternative medicine use: an integrative review. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 6, 409–422, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2014.01.001 (2014).

Mamindla, S., Prasad, K. V. S. R. G. & Koganti, B. Herb-drug interactions: an overview of mechanisms and clinical aspects. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 7, 3576–3586, https://doi.org/10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.7(9).3576-86 (2016).

Boullata, J. I. & Hudson, L. M. Drug-nutrient interactions: a broad view with implications for practice. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 112, 506–517, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.002 (2012).

Newmaster, S. G., Grguric, M., Shanmughanandhan, D., Ramalingam, S. & Ragupathy, S. DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products. BMC Med. 11, 222 (2013).

Wardle, J. Complementary and integrative medicine: the black market of health care? Adv. Integr. Med. 3, 77–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aimed.2017.04.003 (2016).

Farooqui, M. et al. Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) disclosure to the health care providers: a qualitative insight from Malaysian cancer patients. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 18, 252–256, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2012.06.005 (2012).

Singh, V., Raidoo, D. M. & Harries, C. S. The prevalence, patterns of usage and people’s attitude towards complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among the Indian community in Chatsworth, South Africa. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 4, 3 (2004).

Tilburt, J. C. & Miller, F. G. Responding to medical pluralism in practice: a principled ethical approach. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 20, 489–494 (2007).

Forrest, C. B. Primary care gatekeeping and referrals: effective filter or failed experiment? BMJ 326, 692 (2003).

Robinson, A. & McGrail, M. R. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement. Ther. Med. 12, 90–98 (2004).

Adams, J. et al. Research capacity building in traditional, complementary and integrative medicine: grass-roots action towards a broader vision In Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine: An International Reader 275–281 (MacMillan Education UK, 2012).

Agbabiaka, T., Wider, B., Watson, L. K. & Goodman, C. Concurrent use of prescription drugs and herbal medicinal products in older adults: a systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 5, 65 (2016).

Moher, D. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4, 1 (2015).

Stroup, D. F. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283, 2008–2012 (2000).

Shea, B. J. et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, 1013–1020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009 (2009).

Frass, M. et al. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J. 12, 45–56 (2012).

Coggon, D., Barker, D. & Rose, G. Epidemiology for the Uninitiated. (John Wiley & Sons, 2009).

Adams, J. Introduction in Researching Complementary and Alternative Medicine (ed. Adams, J.) xiii–xviii (Routledge, Oxon, 2007).

Hoy, D. et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65, 934–939, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 (2012).

Higgins, J. P. & Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Faith, J., Thorburn, S. & Tippens, K. M. Examining the association between patient-centered communication and provider avoidance, CAM use, and CAM-use disclosure. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 21, 30–35 (2015).

McCrea, C. E. & Pritchard, M. E. Concurrent herb-prescription medication use and health care provider disclosure among university students. Complement. Ther. Med. 19, 32–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2010.12.005 (2011).

Rivera, J. O., Ortiz, M., González-Stuart, A. & Hughes, H. Bi-national evaluation of herbal product use on the United States/México border. J. Herb. Pharmacother. 7, 91–106 (2007).

Tarn, D. M. et al. A cross-sectional study of provider and patient characteristics associated with outpatient disclosures of dietary supplement use. Patient Educ. Couns. 98, 830–836, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.020 (2015).

Herron, M. & Glasser, M. Use of and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine among family practice patients in small rural Illinois communities. J. Rural Health 19, 279–284 (2003).

Giveon, S. M., Liberman, N., Klang, S. & Kahan, E. Are people who use ‘natural drugs’ aware of their potentially harmful side effects and reporting to family physician? Patient Educ. Couns. 53, 5–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00241-6 (2004).

Kuo, G. M., Hawley, S. T., Weiss, L. T., Balkrishnan, R. & Volk, R. J. Factors associated with herbal use among urban multiethnic primary care patients: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 4, 18 (2004).

Tan, M., Uzun, O. & Akcay, F. Trends in complementary and alternative medicine in eastern Turkey. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 10, 861–865 (2004). doi:10.86110.1089/1075553042476623.

Thomas, K. & Coleman, P. Use of complementary or alternative medicine in a general population in Great Britain. Results from the National Omnibus survey. J. Public Health 26, 152–157 (2004).

Wolsko, P. M., Eisenberg, D. M., Davis, R. B. & Phillips, R. S. Use of mind-body medical therapies. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 19, 43–50 (2004).

Braun, C. A., Bearinger, L. H., Halcón, L. L. & Pettingell, S. L. Adolescent use of complementary therapies. J. Adolesc. Health 37(76), e71–79 (2005).

Busse, J. W., Heaton, G., Wu, P., Wilson, K. R. & Mills, E. J. Disclosure of natural product use to primary care physicians: a cross-sectional survey of naturopathic clinic attendees. Mayo Clin. Proc. 80, 616–623 (2005).

Kim, S. et al. A multicenter study of complementary and alternative medicine usage among ED patients. Acad. Emerg. Med. 12, 377–380 (2005).

Shahrokh, L. E., Lukaszuk, J. M. & Prawitz, A. D. Elderly herbal supplement users less satisfied with medical care than nonusers. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 105, 1138–1140 (2005).

Wheaton, A. G., Blanck, H. M., Gizlice, Z. & Reyes, M. Medicinal herb use in a population-based survey of adults: prevalence and frequency of use, reasons for use, and use among their children. Ann. Epidemiol. 15, 678–685 (2005).

Kennedy, J. Herb and supplement use in the US adult population. Clin. Ther. 27, 1847–1858 (2005).

Kennedy, J., Wang, C.-C. & Wu, C.-H. Patient disclosure about herb and supplement use among adults in the US. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 5, 451–456, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/nem045 (2008).

Birdee, G. S. et al. Characteristics of yoga users: results of a national survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 1653–1658, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0735-5 (2008).

Birdee, G. S., Wayne, P. M., Davis, R. B., Phillips, R. S. & Yeh, G. Y. T’ai chi and qigong for health: patterns of use in the United States. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 15, 969–973, https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2009.0174 (2009).

Chao, M. T., Wade, C. & Kronenberg, F. Disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine to conventional medical providers: variation by race/ethnicity and type of CAM. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 100, 1341–1349 (2008).

Faith, J., Thorburn, S. & Tippens, K. M. Examining CAM use disclosure using the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use. Complement. Ther. Med. 21, 501–508, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2013.08.002 (2013).

Wu, C.-H., Wang, C.-C. & Kennedy, J. Changes in herb and dietary supplement use in the U.S. adult population: a comparison of the 2002 and 2007 National Health Interview Surveys. Clin. Ther. 33, 1749–1758, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.09.024 (2011).

Laditka, J. N., Laditka, S. B., Tait, E. M. & Tsulukidze, M. M. Use of dietary supplements for cognitive health: results of a national survey of adults in the United States. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 27, 55–64, https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317511435662 (2012).

Jou, J. & Johnson, P. J. Nondisclosure of complementary and alternative medicine use to primary care physicians: findings from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Intern. Med. 176, 545–546, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8593 (2016).

Saw, J. T., Bahari, M. B., Ang, H. H. & Lim, Y. H. Herbal use amongst multiethnic medical patients in Penang Hospital: pattern and perceptions. Med. J. Malaysia 61, 422–432 (2006).

Shah, B. K., Lively, B. T., Holiday-Goodman, M. & White, D. B. Reasons why herbal users do or do not tell their physicians about their use: a survey of adult Ohio residents. J. Pharm. Technol. 22, 148–154 (2006).

Cheung, C. K., Wyman, J. F. & Halcon, L. L. Use of complementary and alternative therapies in community-dwelling older adults. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 13, 997–1006, https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2007.0527 (2007).

Jean, D. & Cyr, C. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in a general pediatric clinic. Pediatrics. 120, e138–141 (2007).

Xue, C. C. L., Zhang, A. L., Lin, V., Da Costa, C. & Story, D. F. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: a national population-based survey. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 13, 643–650, https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2006.6355 (2007).

Archer, E. L. & Boyle, D. K. Herb and supplement use among the retail population of an independent, urban herb store. J. Holist. Nurs. 26, 27–35 (2008).

Cizmesija, T. & Bergman-Markovic, B. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among the patients in primary health care. Acta Med. Croatica 62, 15–22 (2008).

Hori, S., Mihaylov, I., Vasconcelos, J. C. & McCoubrie, M. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use amongst outpatients in Tokyo, Japan. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 8, 14, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-8-14 (2008).

Ozturk, C. & Karayagiz, G. Exploration of the use of complementary and alternative medicine among Turkish children. J. Clin. Nurs. 17, 2558–2564, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02329.x (2008).

Shakeel, M., Bruce, J., Jehan, S., McAdam, T. K. & Bruce, D. M. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients admitted to a surgical unit in Scotland. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 90, 571–576, https://doi.org/10.1308/003588408X301046 (2008).

Levine, M. A. H. et al. Self-reported use of natural health products: a cross-sectional telephone survey in older Ontarians. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 7, 383–392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.12.003 (2009).

Mc Kenna, F. & Killoury, F. An investigation into the use of complementary and alternative medicine in an urban general practice. Ir. Med. J. 103, 205–208 (2010).

Nur, N. Knowledge and behaviours related to herbal remedies: a cross-sectional epidemiological study in adults in Middle Anatolia, Turkey. Health Soc. Care Community 18, 389–395, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00911.x (2010).

Ben-Arye, E. et al. Integrative pediatric care: parents’ attitudes toward communication of physicians and CAM practitioners. Pediatrics 127, e84–e95, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1286 (2011).

Mileva-Peceva, R., Zafirova-Ivanovska, B., Milev, M., Bogdanovska, A. & Pawlak, R. Socio-demographic predictors and reasons for vitamin and/or mineral food supplement use in a group of outpatients in Skopje. Prilozi 32, 127–139 (2011).

Picking, D., Younger, N., Mitchell, S. & Delgoda, R. The prevalence of herbal medicine home use and concomitant use with pharmaceutical medicines in Jamaica. J. Ethnopharmacol. 137, 305–311, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.025 (2011).

Alaaeddine, N. M. et al. Use of herbal medications and their perceived effects among adults in the Greater Beirut area. J. Med. Liban 60, 45–50 (2012).

Elolemy, A. T. & Albedah, A. M. N. Public knowledge, attitude and practice of complementary and alternative medicine in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. Oman Med. J. 27, 20–26, https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2012.04 (2012).

Kim, J.-H., Nam, C.-M., Kim, M.-Y. & Lee, D.-C. The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in children: a telephone-based survey in Korea. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12, 46, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-46 (2012).

Samuels, N. et al. Use of non-vitamin, non-mineral (NVNM) supplements by hospitalized internal medicine patients and doctor-patient communication. Patient Educ. Couns. 89, 392–398, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.07.005 (2012).

Thomson, P., Jones, J., Evans, J. M. & Leslie, S. L. Factors influencing the use of complementary and alternative medicine and whether patients inform their primary care physician. Complement. Ther. Med. 20, 45–53 (2012).

Zhang, Y., Peck, K., Spalding, M., Jones, B. G. & Cook, R. L. Discrepancy between patients’ use of and health providers’ familiarity with CAM. Patient Educ. Couns. 89, 399–404, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.014 (2012).

Djuv, A., Nilsen, O. G. & Steinsbekk, A. The co-use of conventional drugs and herbs among patients in Norwegian general practice: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 13, 295, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-13-295 (2013).

Chiba, T. et al. Inappropriate usage of dietary supplements in patients by miscommunication with physicians in Japan. Nutrients 6, 5392–5404, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6125392 (2014).

Chin-Lee, B., Curry, W. J., Fetterman, J., Graybill, M. A. & Karpa, K. Patient experience and use of probiotics in community-based health care settings. Patient Prefer. Adherence 8, 1513–1520, https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S72276 (2014).

Nguyen, D., Gavaza, P., Hollon, L. & Nicholas, R. Examination of the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Central Appalachia, USA. Rural Remote Health 14, 1–10 (2014).

Shumer, G. et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use by visitors to rural Japanese family medicine clinics: results from the international complementary and alternative medicine survey. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 14, 360, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-360 (2014).

Vitale, K., Munđar, R., Sović, S., Bergman-Marković, B. & Janev Holcer, N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among family medicine patients - example of the town of Čakovec. Acta Med. Croatica 68, 345–351 (2014).

Chiba, T., Sato, Y., Suzuki, S. & Umegaki, K. Concomitant use of dietary supplements and medicines in patients due to miscommunication with physicians in Japan. Nutrients 7, 2947–2960, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7042947 (2015).

Gyasi, R. M., Siaw, L. P. & Mensah, C. M. Prevalence and pattern of traditional medical therapy utilisation in Kumasi Metropolis and Sekyere South District, Ghana. J. Ethnopharmacol. 161, 138–146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.004 (2015).

Naja, F. et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Lebanese adults: results from a national survey. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 682397 (2015).

Ben-Arye, E., Attias, S., Levy, I., Goldstein, L. & Schiff, E. Mind the gap: Disclosure of dietary supplement use to hospital and family physicians. Patient Educ. Couns. 100, 98–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.037 (2016).

Hsu, O., Tsourounis, C., Chan, L. L. S. & Dennehy, C. Chinese herb use by patients at a San Francisco Chinatown public health center. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 22, 751–756, https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2015.0288 (2016).

Torres-Zeno, R. E., Ríos-Motta, R., Rodríguez-Sánchez, Y., Miranda-Massari, J. R. & Marín-Centeno, H. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Bayamón, Puerto Rico. P. R. Health Sci. J. 35, 69–75 (2016).

Shim, J.-M., Schneider, J. & Curlin, F. A. Patterns of user disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use. Med. Care 52, 704–708 (2014).

Lauche, R., Wayne, P. M., Dobos, G. & Cramer, H. Prevalence, patterns, and predictors of T’ai Chi and qigong use in the united states: results of a nationally representative survey. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 22, 336–342 (2016).

Cramer, H. et al. Prevalence, patterns, and predictors of yoga use: results of a US nationally representative survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 50, 230–235 (2016).

AlBraik, F. A., Rutter, P. M. & Brown, D. A cross‐sectional survey of herbal remedy taking by United Arab Emirate (UAE) citizens in Abu Dhabi. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 17, 725–732 (2008).

Aydin, S. et al. What influences herbal medicine use?-prevalence and related factors. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 38, 455–463 (2008).

Bruno, J. J. & Ellis, J. J. Herbal use among US elderly: 2002 national health interview survey. Ann. Pharmacother. 39, 643–648 (2005).

Canter, P. H. & Ernst, E. Herbal supplement use by persons aged over 50 years in Britain. Drug Aging 21, 597–605 (2004).

Chang, M.-Y., Liu, C.-Y. & Chen, H.-Y. Changes in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Taiwan: a comparison study of 2007 and 2011. Complement. Ther. Med. 22, 489–499 (2014).

Cincotta, D. R. et al. Comparison of complementary and alternative medicine use: reasons and motivations between two tertiary children’s hospitals. Arch. Dis. Child. 91, 153–158 (2006).

Clement, Y. N. et al. Perceived efficacy of herbal remedies by users accessing primary healthcare in Trinidad. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 7, 4 (2007).

Delgoda, R., Younger, N., Barrett, C., Braithwaite, J. & Davis, D. The prevalence of herbs use in conjunction with conventional medicines in Jamaica. Complement. Ther. Med. 18, 13–20 (2010).

Gardiner, P., Graham, R., Legedza, A. T. & Ahn, A. C. Factors associated with herbal therapy use by adults in the United States. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 13, 22 (2007).

Gardiner, P., Sadikova, E., Filippelli, A. C., White, L. F. & Jack, B. W. Medical reconciliation of dietary supplements: Don’t ask, don’t tell. Patient Educ. Couns. 98, 512–517 (2015).

Lim, M., Sadarangani, P., Chan, H. & Heng, J. Complementary and alternative medicine use in multiracial Singapore. Complement. Ther. Med. 13, 16–24 (2005).

Low, E., Murray, D., O’Mahony, O. & Hourihane, J. B. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Irish paediatric patients. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 177, 147–150 (2008).

MacLennan, A. H., Myers, S. P. & Taylor, A. W. The continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine in South Australia: costs and beliefs in 2004. Med. J. Aust. 184, 27 (2006).

Najm, W., Reinsch, S., Hoehler, F. & Tobis, J. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among the ethnic elderly. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 9, 50 (2003).

Robinson, N. et al. Complementary medicine use in multi-ethnic paediatric outpatients. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 14, 17–24 (2008).

Rolniak, S., Browning, L., MacLeod, B. A. & Cockley, P. Complementary and alternative medicine use among urban ED patients: prevalence and patterns. J. Emerg. Nurs. 30, 318–324 (2004).

Shive, S. E. et al. Racial differences in preventive and complementary health behaviors and attitudes. J. Health Dispar. Res. Pract. 1, 6 (2007).

Shorofi, S. & Arbon, P. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among hospital patients: an Australian study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 16 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.09.009 (2010).

Zhang, A. L., Xue, C. C., Lin, V. & Story, D. F. Complementary and alternative medicine use by older Australians. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1114, 204–215 (2007).

Stevenson, F. A., Britten, N., Barry, C. A., Bradley, C. P. & Barber, N. Self-treatment and its discussion in medical consultations: how is medical pluralism managed in practice? Soc. Sci. Med. 57, 513–527 (2003).

Shelley, B. M. et al. ‘They don’t ask me so I don’t tell them’: patient-clinician communication about traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine. Ann. Fam. Med. 7, 139–147, https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.947 (2009).

Arcury, T. A. et al. Attitudes of older adults regarding disclosure of complementary therapy use to physicians. J. Appl. Gerontol. 32, 627–645, https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464812443084 (2013).

Jang, D. J. & Tarn, D. M. Infrequent older adult-primary care provider discussion and documentation of dietary supplements. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62, 1386–1388, https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12915 (2014).

Lorenc, A., Crichton, N. & Robinson, N. Traditional and complementary approaches to health for children: modelling the parental decision-making process using Andersen’s Sociobehavioural Model. Complement. Ther. Med. 21, 277–285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2013.05.006 (2013).

Araz, N. & Bulbul, S. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in a pediatric population in southern Turkey. Clin. Invest. Med. 34, E21–E29 (2011).

Gottschling, S. et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in healthy children and children with chronic medical conditions in Germany. Complement. Ther. Med. 21, S61–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2011.06.001 (2013).

Roberts, C. S. et al. Patient-physician communication regarding use of complementary therapies during cancer treatment. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 23, 35–60 (2005).

Pinto, R. Z. et al. Patient-centred communication is associated with positive therapeutic alliance: a systematic review. J. Physiother. 58, 77–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70087-5 (2012).

Xu, S. & Levine, M. Medical residents’ and students’ attitudes towards herbal medicines: a pilot study. Can. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 15, e1–e4 (2008).

Winslow, L. C. & Shapiro, H. Physicians want education about complementary and alternative medicine to enhance communication with their patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 162, 1176–1181 (2002).

Wetzel, M. S., Eisenberg, D. M. & Kaptchuk, T. J. Courses involving complementary and alternative medicine at US medical schools. JAMA 280, 784–787, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.9.784 (1998).

Ruedy, J., Kaufman, D. M. & MacLeod, H. Alternative and complementary medicine in Canadian medical schools: a survey. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 160, 816–817 (1999).

Smith, K. R. Factors influencing the inclusion of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in undergraduate medical education. BMJ Open 1, e000074, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000074 (2011).

Brinkhaus, B. et al. Integration of complementary and alternative medicine into German medical school curricula - contradictions between the opinions of decision makers and the status quo. Complement. Med. Res. 12, 139–143 (2005).

Frei, M., Ausfeld-Hafter, B., Fischer, L., Frey, P. & Wolf, U. Establishing a curriculum in complementary medicine within a medical school on the example of the University of Bern, Switzerland. Explore (NY) 9, 322 (2013).

Oberbaum, M., Notzer, N., Abramowitz, R. & Branski, D. Attitude of medical students to the introduction of complementary medicine into the medical curriculum in Israel. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 5, 139–142 (2003).

Greiner, K. A., Murray, J. L. & Kallail, K. J. Medical student interest in alternative medicine. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 6, 231–234 (2000).

Roter, D. L. et al. Communication predictors and consequences of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) discussions in oncology visits. Patient Educ. Couns. 99, 1519–1525, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.002 (2016).

Michaud, P., Jucker-Kupper, P. & members of the Profiles Working Group. PROFILES: Principle Objectives and Framework for Integrated Learning and Education in Switzerland (ed Joint Commission of the Swiss Medical Schools) (Joint Commission of the Swiss Medical Schools, Bern, 2017).

Ben-Arye, E., Halabi, I., Attias, S., Goldstein, L. & Schiff, E. Asking patients the right questions about herbal and dietary supplements: cross cultural perspectives. Complement. Ther. Med. 22, 304–310, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2014.01.005 (2014).

Caspi, O. et al. On the definition of complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine: societal mega-stereotypes vs. the patients’ perspectives. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 9, 58–62 (2003).

Anbari, K. & Gholami, M. Evaluation of trends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in health centers in Khorramabad (West of Iran). Glob. J. Health Sci. 8, 72–76, https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n2p72 (2015).

Avogo, W., Frimpong, J. A., Rivers, P. A. & Kim, S. S. The effects of health status on the utilization of complementary and alternative medicine. Health Educ. J. 67, 258–275 (2008).

Desai, K., Chewning, B. & Mott, D. Health care use amongst online buyers of medications and vitamins. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 11, 844–858, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.01.001 (2015).

Emmerton, L., Fejzic, J. & Tett, S. E. Consumers’ experiences and values in conventional and alternative medicine paradigms: a problem detection study (PDS). BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12, 39–39, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-39 (2012).

Featherstone, C., Godden, D., Selvaraj, S., Emslie, M. & Took-Zozaya, M. Characteristics associated with reported CAM use in patients attending six GP practices in the Tayside and Grampian regions of Scotland: a survey. Complement. Ther. Med. 11, 168–176 (2003).

Harnack, L. J., DeRosier, K. L. & Rydell, S. A. Results of a population-based survey of adults’ attitudes and beliefs about herbal products. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 43, 596–601 (2003).

Hunt, K. J. et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in England: results from a national survey. Int. J. Clin. Prac. 64, 1496–1502, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02484.x (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among primary care patients in West Texas. South. Med. J. 101, 1232–1237, https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181840bc5 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Andrea Trubody and Rebecca Reid for their contributions during the initial stages of the development of this review’s protocol. We also wish to thank Boyd Potts and Tess Dingle for assistance and feedback on statistics and graphics. Hope Foley was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship while working on this manuscript. Distinguished Professor Jon Adams was supported by an Australian Research Council Professorial Future Fellowship while working on this manuscript (Grant FT140100195). Dr Jon Wardle was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Translating Research into Practice Fellowship while working on this manuscript (Grant 1133136). No funding sources played any role in the study design; data collection, analysis or interpretation; drafting or editing of the manuscript; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.F. and A.S. conceived of the design and methodology for this review. H.F. developed the review protocol and searched the literature with input and support from A.S. H.F., A.S. and H.C. analysed the results, and interpreted the results in conjunction with J.W. and J.A. H.F. developed the initial draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to writing, critically editing, revising, and approving the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. H.F. is guarantor, held full access to all data, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foley, H., Steel, A., Cramer, H. et al. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 9, 1573 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38279-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38279-8

This article is cited by

-

Views of healthcare professionals on complementary and alternative medicine use by patients with diabetes: a qualitative study

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies (2024)

-

Integrative Oncology Approaches to Reduce Recurrence of Disease and Improve Survival

Current Oncology Reports (2024)

-

Cancer patients’ behaviors and attitudes toward natural health products

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies (2023)

-

Allopathic Medicine Practitioners’ perspectives on facilitating disclosure of traditional medicine use in Gauteng, South Africa: a qualitative study

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies (2023)

-

Terminally ill patients’ and their relatives’ experiences and behaviors regarding complementary and alternative medicine utilization in hospice palliative inpatient care units: a cross-sectional, multicenter survey

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.