Abstract

Microalga is a promising biomass feedstock to restore the global carbon balance and produce sustainable bioenergy. However, the present biomass productivity of microalgae is not high enough to be marketable mainly because of the inefficient utilization of solar energy. Here, we study optical engineering strategies to lead to a breakthrough in the biomass productivity and photosynthesis efficiency of a microalgae cultivation system. Our innovative optical system modelling reveals the theoretical potential (>100 g m−2 day−1) of the biomass productivity and it is used to compare the optical aspects of various photobioreactor designs previously proposed. Based on the optical analysis, the optimized V-shaped configuration experimentally demonstrates an enhancement of biomass productivity from 20.7 m−2 day−1 to 52.0 g m−2 day−1, under the solar-simulating illumination of 7.2 kWh m−2 day−1, through the dilution and trapping of incident energy. The importance of quantitative optical study for microalgal photosynthesis is clearly exhibited with practical demonstration of the doubled light utilization efficiencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photosynthesis is the principle process by which life converts solar energy and CO2 into reduced and functional carbon forms and is the product of billions of years of evolution. The global photosynthetic rate of ~130 TW1,2 secures environmental homeostasis by maintaining the carbon balance between land and atmosphere. However, since the industrial revolution, humans have increasingly rapidly burned carbon chemicals (~16 TW)3 accumulated over the last 100 million years, causing carbon imbalance and, consequently, increasingly daunting global climate change on Earth. Therefore, renewable energy alternatives must be developed and implemented in a multilateral and unceasing manner4,5,6,7. The depletion of the finite chemical energy resources is another reason to pursue such alternatives, especially because of the necessity of carbon-based liquid fuels for transportation (~4 TW)8 at least for the near future. Biofuels are generally viewed as a solution: they are produced in a continuous manner and reduce CO2 in the process. However, this potentially green solution, particularly to become effectively commercialized, has many issues that must be overcome. The most important issue is the requirement for large amounts of arable land: at least 6 more Amazon rainforests9,10,11 are required to meet the 4 TW demand through the cultivation of terrestrial plants such as grains and trees.

One promising alternative to terrestrial biomass feedstock is microalgal biomass. These phototrophic microorganisms achieve a 10- to 50-fold higher photosynthesis rate (PR) than terrestrial plants12,13,14; therefore, they need a far smaller land area for biomass production than their terrestrial counterparts. Nevertheless, there exist plenty of challenges for production of microalgal biomass with monoculture, such as avoiding contamination, enhancing lipid contents, and reducing production cost. In particular, we focus on the fact that the present biomass productivity of 10–20 g m−2 day−1 in open-pond cultivation systems, which are advantageous for scaling up and for mass production, is far from profitable, especially in the form of fuels12,13,14,15. Given that such a low productivity has much do with the exceedingly limited utilization of the incoming light, ingenious optical engineering can offer a breakthrough in tackling this otherwise almost insurmountable challenge. Previous attempts can broadly be classified into two: (i) quantity control for diluting strong incident light energy with light guides16,17,18,19,20,21,22, vertically or obliquely installed reactors23,24,25,26, tubular or spiral design27,28,29,30,31,32,33, or increased surface areas34,35,36,37; and (ii) quality control for effectively utilizing the solar spectrum with luminescent materials38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Although these efforts are useful in various ways, the comprehension of optical behavior of microalgae in particular is greatly lacking, which fundamentally hampers design innovation able to overcome such limited performance.

The present study aims to make the best of the optical engineering for the purpose of maximizing the biological counterpart, namely, microalgal photosynthesis; and in so doing, establishing general and specific design rules encompassing economically viable optical strategies in a way that extracts the full potential of microalgal biomass productivity. Based on a 3D profile analysis for refractive indices of algal cells, a realistic model for photosynthetic systems is proposed to better understand the macroscopic behaviour of the photosynthetic microbes. The theoretical analysis predicts that biomass productivity can reach ~140 g m−2 day−1 by way of light energy redistribution under high illumination. To realize this theoretical potential in a practical sense, which is directly applicable to an open pond, a V-shaped cultivator is chosen. When the light energy is efficiently diluted and trapped by adopting the V-shaped bioreactor under an illumination of 7.2 kWh m−2 day−1, the biomass productivity is experimentally shown to be improved more than 2.5-fold, from 20.7 g m−2 day−1 to 52.0 g m−2 day−1.

Results and Discussion

Experimental design

For the microalgal research, the large-scale outdoor cultivation and lab-scale indoor evaluation have strong pros and cons of each. The outdoor cultivation provides the same environmental condition as the real world application and it is considered to be more trustworthy in the industry; however, its environmental dependence, uncontrollability, and high installation cost have been a high barrier to entry for scientific investigation and innovative challenges. On the other hand, despite the convenience and controllability, lab-scale indoor experiments have been considered to be rarely reproducible in the real-world. Therefore, this research has focused on the establishment of a rigorous outdoor-simulating cultivation system, which would bring the system design work to the field of academic research. A metal halide lamp with proper spectral filters (K3700, McScience, Korea) was adopted to simulate outdoor conditions. Within the wavelength range of 400–800 nm, the relative portions of the photons in 400–500 nm, 500–600 nm, 600–700 nm and 700–800 nm were 28%, 27%, 29%, and 16%, on average, while those are 26%, 28%, 26%, and 21% in the real sunlight with the spectrum of AM 1.5 G, exhibiting only a reasonable deviation of a few percent in the visible range. The illumination intensities were maintained within 0.55–0.60 sun by using a photodiode detecting 300–800 nm, where 1 sun intensity corresponds to 1000 W m−2 for AM 1.5 G and visible photons of 2000 μmol m−2 s−1 (=2000 μE m−2 s−1). A photoperiod of 12 h:12 h (light:dark) was adopted to simulate the daily variation of the solar illumination, but the hourly variation of its intensity was not taken into account here due to technical limitation. Continuous illumination during daytime may overestimate the real-world biomass productivity by reducing the peak intensity and alleviating the difficulties of cells to adjust the photosynthetic machinery to variations in light intensity. Such overestimation would decrease in the light diluting schemes, which will be discussed in this manuscript, and we leave more precise investigation of the effect of such hourly intensity variation as a future work. The illumination of 0.6 sun with this photoperiod corresponds to 7.2 kWh m−2 day−1. The illumination area of each bioreactor was confined by apertures and the sides of the reactors were covered by metal (aluminium foil or a stainless steel wall), which prevented overestimation caused by undesirable photon influx from the outside and realized the periodic boundary condition, making it possible for a laboratory-scale reactor to simulate a large system. All the bioreactors were entirely covered by the transparent covers with the same transparent material (i.e. polycarbonate) regardless of their geometry, in order to focus on their geometrical effects rather than material characteristics such as UV-cutting effect. The validity of our system design and corresponding scalability of the system will be demonstrated in our experimental results later.

Optical study of microalgal photosynthesis

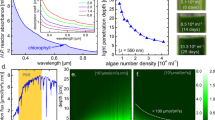

Previous optical studies have viewed photosynthesis in a bioreactor as a macroscopic phenomenon47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56; therefore, the microscopic optical characteristics of the cells inside the reactor have been rarely studied, and their importance has been scarcely noticed. Here, optical diffraction tomography57,58 was used to investigate the biochemical and morphological properties of microalgal cells. Figures 1a and S1 illustrate the 3D refractive index distribution of individual microalgal cells measured at the wavelength of 532 nm. The measured 3D refractive index tomograms of microalgal cells clearly show that individual cells are composed of highly inhomogeneous refractive index distributions and also have refractive indices of 1.36–1.46, which are higher than that of surrounding media (water, n = 1.33). Thus, significant amounts of light scattering events can be expected, particularly when there exists large number of microalgal cells. This phenomenon can be quantitatively analysed using the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method based on the tomogram (refer to supplementary information (SI)) in Fig. 1b. Such light scattering, although nominal (<2°) with a single cell, becomes substantial with a number density of 107–108 cells mL−1 (refer to SI (Fig. S2)).

Optical characteristics of microalgal cells. (a) 3D profile of the refractive index (n) of a Chlorella vulgaris cell. (b) Volume distribution of the refractive index in the Chlorella vulgaris cell (above) and the calculated angular distribution of light scattered by a single cell. (c) Picture of a top-illuminated bioreactor (first), ray-traced image of custom-made optical simulation (second), and simulated light absorption (in log scale) with depth under red (680 nm), green (530 nm), blue (440 nm), and solar (AM 1.5 G) illumination (third, the background image is for the AM 1.5 G absorption profile on a linear scale). (d) Experimentally measured (black) or modelled (red, green, and blue for the models based on Eqs 1–3, respectively) areal biomass productivity for various illumination (inset: action spectrum used for the modelling and optical density (O.D.) measured for Chlorella vulgaris).

Light absorption and scattering of the cells result in the uneven distribution of the light energy inside a bioreactor, as shown in the first image of Fig. 1c. As photons are blocked by the cells near the water’s surface, light energy is mostly concentrated within a few centimetres, as is photosynthetic activity; consequently, a negligible degree of photosynthesis occurs in the remainder of the cultivation volume.

Monte Carlo Method can be adopted to investigate and visualize such optical properties59,60,61. To mimic the macroscopic behaviour of microalgae, we designed triangular bubbles and used them as cells for a custom-made optical simulation, as shown in the second image (refer to SI (Fig. S3)). The calculated absorption profiles for red (680 nm), green (530 nm), blue (440 nm), and solar (AM 1.5G) illuminations are shown in the third image of Fig. 1c. Green photons and AM 1.5 G light reach deeper than blue and red photons, which have relatively high extinction coefficients. Such optical characteristics result in a sub-linear productivity with respect to illumination, as shown in Fig. 1d; consequently, the corresponding photosynthesis efficiency (PE) becomes low under increased illumination. The black dots in Fig. 1d represent the experimentally achieved biomass productivity of microalgae (Chlorella vulgaris) under various artificial solar illuminations (AM 1.5G).

Modelling of microscopic responses of microalgae will deepen our understanding of their photosynthetic mechanism and the resulting macroscopic behaviours of the photosynthetic system. In previous related studies47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56, the PR is mostly represented by a single fitting equation with a sole parameter of total illumination, which ignores the aforementioned optical energy distribution. In the present study, the microscopic PR profile is newly expressed as a function of (x, z) position modifying the macroscopic models previously proposed. Then, the macroscopic biomass productivity can be obtained by integrating the spatial PR for a whole system. Figure 1d compares such integrated biomass productivities using 3 different models with our experimental results, where the model 149,50,56, 247,48 and 354 are based on

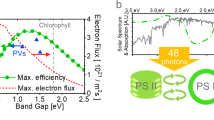

respectively, where Cvolume is the cell biomass concentration, assumed to be 1.4 g L−1, which is the average saturated biomass concentration in our experiments, and #Ph.(λ, x, z) is the number rate of absorbed photons per volume at a given wavelength and position. Rmax is a constant for the effective maximum PR per weight, influenced by several biological or environmental parameters (species, nutrient, aeration, etc.). Aaction(λ) is an absorbed-light action spectrum defined as the ratio of photons used for photosynthesis to the total photon absorption at a given wavelength; our chosen species Chlorella vulgaris is assumed to have the same spectrum as Chlorella pyrenoidosa from previous reports, as shown in the inset of Fig. 1d62,63. Aaction(λ) is relatively low under blue light and becomes ~84% for the entire visible light spectrum. Because 48 photons in total are consumed to produce one glucose molecule (29.8 eV) during the photosynthesis process, at least 57 visible photons should be absorbed per 29.8 eV bioenergy produced under low illumination (i.e., ΔPR(x, z)/Δ#Ph.(x, z)|#Ph.→0 = 29.8 eV/57 photons = 8.36 × 10−20 J/photon). This value is the same as that experimentally predicted by others64,65. Ihalf in Eq. 2 indicates the absorbed active photon densities (=∫ Aaction(λ) × #Ph.(λ, x, z) dλ) for PR reaching the half maximum value, and Imax in Eq. 3 indicates that for the maximum value. Here, as a boundary condition, we assumed that 57 visible incident photons (i.e. ∫ Aaction(λ) × #Ph.(λ) dλ = 48) are completely consumed to produce one glucose molecule under the extremely low illumination; then, Ihalf and Imax become dependent variables equal to Cvolume × Rmax × 48/(29.8 eV) and 2 × Cvolume × Rmax × 48/(29.8 eV), respectively, and Rmax is the only parameter to be fitted. Figure 1d reveals that the experimental results for flat bioreactors under various illuminations are well matched with our models assuming Rmax = 0.30 W g−1 for (1) and Rmax = 0.40 W g−1 for (2) and (3). It should be noted that we succeeded in fitting our models to the experimental results even without the terms for photoinhibition and weight loss from respiration, which appear in many previous models and should be considered important. The exclusion of those terms made our model very simple, minimizing the unknown variables; and it was validated by the facts that (i) all our experiments were based on closed photobioreactors with plastic covers absorbing harmful ultraviolet light; and (ii) Rmax fitted to the experimental results can roughly reflect the effect of respiration loss (refer to SI for details). While all the models well represent the optical saturation property of photosynthesis, we chose Eq. 1 for calculating the spatial photosynthesis rates in the rest of this manuscript.

Figure 2a shows the volumetric PR (W L−1) inside the top-illuminated flat cultivator based on our new system. A biomass productivity of 12.5 g m−2 day−1 is estimated under 1.2 kWh m−2 day−1, which corresponds to 12 hours of 0.1 sun (visible photons of 200 μmol m−2 s−1) illumination, which is a quantitatively similar light intensity to typical light-emitting diodes (LEDs). A combustion heat of 4.2 kcal g−1 is obtained from the experiments. Under this condition, the photosynthetic efficiency (PE) of biomass energy is found to be 5.1%. Under such low illumination, the number of photons works as the most deterministic factor of photosynthesis, and the total productivity almost proportionally increases along with the illumination, as shown in Fig. 1d. Under an illumination of 3.6 kWh m−2 day−1 (12 hours of 0.3 sun), which corresponds to the annual average outdoor condition of South Korea, the biomass productivity is increased to 18.7 g m−2 day−1. Compared with the 1.2 kWh m−2 day−1 illumination, as shown in Fig. 2a, photosynthesis occurs more deeply and more intensively; the 50% increase in total productivity, by contrast, is much less than a 3-fold illumination boost; therefore, the PE is reduced to 2.5%. This reduced efficiency occurs because the photon flux is saturated near the surface. Likewise, under a higher illumination of 7.2 kWh m−2 day−1 (12 hours of 0.6 sun), which corresponds to the daily illumination of the world’s hottest regions (such as the Sahara Desert and the Andes Mountains), the biomass productivity increases to 22.8 g m−2 day−1; however, the PE drops to 1.5%, as the excess photons are not efficiently utilized. It should be noted that the areal productivity of 22.8 g m−2 day−1 corresponds to the volume productivity (=areal productivity/reactor depth) of 0.46, 0.23, and 0.08 g L−1 day−1 for the reactors with a depth of 5, 10, and 30 cm, respectively. Such optical inefficiency, unless resolved, thwarts the installation of photosynthetic systems in highly illuminated places.

Optical study of microalgal cultivation system. (a) Simulated photosynthesis rate profiles and expected biomass productivities under 0.1 sun (first), 0.3 sun (second), and 0.6 sun (third) illuminations. (b) Simulated photosynthesis rate profiles under 0.6 sun with an increased light propagation of 2Dprop and 4Dprop. (c) Expected biomass productivities of the systems in (a,b) and the ideal reactor under various illuminations. (d) Concept of cultivation building with multiple stacks.

Effective alleviation of the optical inefficiency, particularly under high illumination, is therefore a key to achieving an economically feasible level of biomass productivity. For a biomass concentration of 1.4 g L−1, which was assumed here, a light propagation depth (Dprop) of 1/α (α: 2.1 cm−1) is only 0.47 cm. As shown in Fig. 2b, hypothetically assuming that photons can propagate twice and 4 times deeper with the same cell concentration, the expected biomass productivity would be increased to 38.7 g m−2 day−1 and 60.3 g m−2 day−1, respectively, even under the same illumination. Figure 2c presents the expected biomass productivity of those virtual conditions as a function of illumination. The productivity difference increases under higher illumination, whereas the productivity is nearly saturated in the original system. In particular, for an ideal system, which sufficiently dilutes incident light, a PE of 9.7% can be achieved for all illumination conditions, and a biomass productivity of ~140 g m−2 day−1 is achievable under high illuminations of >7.2 kWh m−2 day−1. While the genetic engineering approach must be continuously sought to increase Dprop by reducing the absorption cross-section of each cell64, optical approaches with system design would possibly offer an equally effective and/or synergistically better means to it. A futuristic, potentially ideal cultivation system can be constructed as a form of cultivation building by inserting light guides into the deep or multiply stacked bioreactor, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 2d16,17,18,19,20,21,22. In the cultivation building, light energy can be evenly distributed through the guides such as optical fibers; however, this concept has been rarely realized before and there are inevitable limitations associated with it, such as structural complexity, high-cost installation of optical components, and high-cost operation of light tracking, which must be accompanied to fix the focus of concentrated light to the light guide according to the solar movement. As a more practical light dilution approach, planar or tubular type photobioreactors are widely used23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33, but performance is inferior to the ones in Fig. 2c, as discussed in the next section.

Practical configuration for boosting productivity

To realize the light dilution in an easily implementable fashion, we modified the configuration of shown in Fig. 2d in such a way that each stack is inclined, as shown in Fig. 3a. As a result, the incident sunlight is evenly distributed among the stacks without requiring high-cost optical components. This scheme converges to a V-shaped array cultivator25,26,27, as presented in Fig. 3b, of which concept is simple and easy, but has been less spotlighted and rarely studied scientifically. The inclined surfaces of the V-shaped system receive sunlight over a larger area, and the light intensity is diluted by sin(θv/2), where θv is the vertex angle. Hence, the V-shaped configuration is equivalent to the system shown in Fig. 2b with Dprop’=Dprop/sin(θv/2) or the cultivation structure in Fig. 2d with 1/sin(θv/2) stacks. If the system is aligned along the east-to-west line and properly tilted according to the latitude of the installed location, the incident angle of sunlight at noon can be restricted within only ±23.5° from the normal line for an entire year66,67,68,69. The system can be alternatively realized by implementing a V-shaped cover on top of a raceway pond (inset of Fig. 3b), which makes the V-shaped system economically more viable compared to previous light propagation enhancement systems that are mostly restricted to photobioreactor types or use high-cost optical components70,71,72. The V-shaped scheme is very scalable as well (refer to SI (Fig. S4)); what is better, the material cost does not depend on the depth of the pond. The cover can be made of various transparent materials and it would increase the installation cost. However, the cost would be compensated for by an enhanced algae productivity of more than 100%. The techno-economic analysis shown in SI (Fig. S6) reveals the V-shaped cover has a potential for reducing the microalgal biomass selling price from ~US$540 ton−1 to ~US$280 ton−1 in an open pond with the improved productivity. Moreover, by blocking the interface with air, the implementation of the cover would also be beneficial for reducing the operation cost by minimizing water evaporation, which accounts for up to 67% of the total water use, and CO2 consumption, which mostly escapes to the air due to a low water solubility and accounts for 15–20% of the total price of the dry biomass15.

Optical modelling for V-shaped microalgal cultivation. (a) Cultivation building modified to the V shape. (b) V-shaped cultivation array system. (inset: a raceway pond with a V-shaped cover) (c) Simulated absorption (left) and photosynthetic rate (right) profiles of the V-shaped system (inset: those for flat systems) (d) Average photosynthesis rate as a function of depth. (e–g) Calculated Fresnel reflection loss on the surface of (e) the flat system, (f) the vertical plate, and (g) the V-shaped system for an incident angle change parallel (angle 1) or perpendicular (angle 2) to the cross-section plane.

Our optical system modelling of photosynthesis enables the prediction of the photosynthetic performance for non-planar-type cultivation. Figure 3c shows a simulated optical energy distribution in a V-shaped system with θv = 30°, which is equivalent to the cultivation structure comprising 3.9 stacks. Compared to the flat system (inset), incident light reaches much deeper and the integrated photosynthesis depth profile becomes more uniform, as shown in Fig. 3d. The total biomass productivity is expected to be 49.6 g m−2 day−1, which is 118% higher than that of the flat system and between those for Dprop’ = 2 Dprop and Dprop’ = 4 Dprop (Fig. 2b,c).

In fact, the V-shaped configuration was proven to be one of the most efficient light-trapping schemes in a PV study67,73,74. Figure 3e–g present the Fresnel reflection loss on the air/glass/water interfaces of a ground-type reactor, a vertical plate reactor, and a V-shaped reactor, respectively. As the Fresnel reflection increases as the incident angle increases, the reflection loss is considerable, especially in the vertical plate; the loss becomes highest at small angles 1 and 2 (inset of Fig. 3e), which correspond to summer or noon with high illumination. Therefore, a large amount of loss follows. However, such losses can be almost fully avoided by the V-shaped geometry because the photons escaping from one side can enter the opposite side.

Comparative study of various configurations

While there have been numerous approaches previously proposed for light dilution, the system modelling designed here makes it possible to quantitatively compare the different geometry and optimize the best architecture. To make a general comparison, we classified and simplified the previously proposed configurations into a few 2D cross-sectional geometries including (i) horizontally placed planar geometry (e.g. open-pond, top-illuminated bioreactors with a flat surface, etc.); (ii) vertically placed planar geometry obliquely receiving sunlight (e.g. vertical plat panel, vertical cylinder, etc.); (iii) horizontally placed circles array (e.g. horizontal tubular bioreactors, etc.); and (iv) vertically placed circles array (e.g. fence tubular, helical tubular, spiral bioreactors, etc.), varying vertex angle of V-shape or radius of circles as shown in Fig. 4. The illumination was roughly assumed to be 7.2 cos(θi) kW m−2 day−1 where θi indicates the incident angle on the cross-sectional plane of each system shown in Fig. 4b. For the vertical systems, the geometrical fill factor was assumed to be dense enough to absorb the full illumination without optically dead area on the ground.

Comparative study for various cultivation systems. (a) Calculated areal biomass productivities of V-shaped cultivators (θv = 30°, 60°, and 90°, denoted by V30, V60, and V90, respectively) and planar (P) or tubular (T10 for diameter of 10 cm and T4 for diameter of 4 cm) cultivators horizontally or vertically installed on the ground as a function of the incident angle on the cross-sectional plane. (b) Photosynthesis rate (PR) profiles inside the systems in (a) with the same scale bar, at the incident angle of 0° for the horizontally installed systems and 30° for the vertically installed systems as represented by the arrows.

The V-shaped systems with vertex angles of 30° and 60° are shown to much outperform the other systems near the normal incident angle (θi = 0°), while that of 90° is similar to the one for tubular reactor with a diameter of 10 cm. The biomass productivity at the normal angle is shown to increase as the vertex angle decreases and the factor of light dilution (=1/sin(θv/2)) increases. On the other hand, for the larger incident angle (θi > 1/sin(θv/2), the incident light impinges on only one side of the V-shaped bioreactor, and the illuminated area decreases as the angle increases further. As a result, the light dilution effect is reduced and the productivity drops rapidly. Concentrating the light dilution effect near the normal incident angle is an effective strategy since the diluting effect is especially critical for the high illumination with the high altitude of the sun. Aligning the bioreactor can further minimize the cross-sectional angle variation as described in Fig. 3b; the annual variation of the incident angle at noon can be restricted to ±23.5°.

The horizontally installed planar bioreactor has shown the minimum variation of the productivity along the variation of the incident angle, since the factor of light dilution is always 1 regardless of the incident angle. On the other hand, the effect of light dilution was shown to be not significant for the vertically installed planar reactor for all angles, despite a dilution ratio of 1/sin(θi). In the vertical systems, the angle between the light and surface becomes shallow as the incident angle decreases, and the corresponding Fresnel reflection increases, as discussed in Fig. 3f; the productivity becomes particularly very low near the normal incident angle. Moreover, the increased cost for high density installation to prevent the optical loss also plays a negative impact on their economic viability.

Tubular reactors may compensate for such limitations of the planar reactors. The circular surface itself has a light dilution effect in manner that increases the surface area by π/2 and reduces the Fresnel reflection loss by geometrically guiding the reflected light. Hence, biomass productivity of the horizontally installed tubular system can be higher than that for the planar system at some angles. For the diameter of 4 cm that is comparable to the optical propagation distance in dimension, the geometrical effect is relatively low and the performance is close to that for planar system.

It is this reason that we determined the V-shaped configuration as the most efficient system among the examined candidates, at least in the optical point of view. In addition to this, the V-shaped system is distinctively advantageous in that implementation is easily done by simply placing plastic cover on top of an open-pond, while vertical and/or tubular bioreactors are inherently costly. More precise comparison of non-optical efficiencies such as shaking and aeration, possibly influenced by geometry, remains as a future work.

Experimental demonstration

Experimentally, we constructed a V-shaped physical bioreactor with θv = 30°, as shown in Figs 5a and S7. Under 0.60 sun and 12 h:12 h (light:dark) conditions, the growth profiles with different system depths are presented in Fig. 5b–d. Although the volume concentration is saturated more quickly in the shallow system than in the deep system, the total growth rate per given illumination area is shown to be almost similar, 52.0 g m−2 day−1 on average, which is 2.5 times higher than that of the flat bioreactor (20.7 g m−2 day−1). The PE was also improved from 1.40% to 3.52%, in accordance with the our modelling results of the system (Figs 2c and 3c). The consistent productivity even with a small-volume V-shaped bioreactor can be attributed to the light-trapping effect, which makes it possible to compensate for the short optical path length of shallow depth. The final cell concentration tends to be higher for systems with small volumes, yielding a higher economic viability by reducing the cost for product drying, water supply, and nutrient preparation. The enhanced microalgal growth in a V-shaped bioreactor was consistently demonstrated in several repeated experiments with semi-continuous cultivation, varied environmental conditions, and a large-volume cultivation system as shown in SI (Fig. S5).

Experimental demonstration of V-shaped microalgal cultivation. (a) Photograph and diagram of the V-shaped bioreactors used in the experiment. (b,c) Measured (b) volume and (c) area concentration of microalgal cells during growth in the flat and V-shaped systems with various depths. (d) Volume and area productivities of microalgal biomass in the V-shaped systems with various depths.

The main purpose of this research indeed lies not in proposing a single outstanding scheme per se, though we believe ours is such a one indeed, but rather in applying a quantitative optical engineering approach to microalgae research, which has rarely been done in a systematic way. The V-shaped configuration is a mere example proposed through the optical study by means of comparing and integrating all types of previous attempts. Beyond the academic studies, real-world scale demonstration of the proposed scheme would necessarily be a future step for commercializing microalgae and contributing to recovering global carbon balance. The practical issues such as water circulation affected by V-shaped cover, off-gassing of generated oxygen, and lifetime of plastic components, which have not been deeply investigated here, could be raised for scaling up the schemes. Moreover, analysis of lipid contents of biomass, critical for biofuel extraction, as a function of light input and integration with genetic engineering would bring further benefits for the economic viability of microalgal biomass.

Materials and Methods

Cultivation environment

Chlorella vulgaris from the University of Texas (UTEX-265) was cultivated in a BG-11 medium, which contained 1.5 g L−1 of NaNO3, 0.075 g L−1 of MgSO4·7H2O, 0.020 g L−1 of Na2CO3, 0.036 g L−1 of CaCl2·2H2O, 0.006 g L−1 of citric acid, 0.001 g L−1 of disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate (Na2EDTA), 0.040 g L−1 of K2HPO4, 0.006 g L−1 of ammonium ferric citrate, and 0.1% v/v of trace element solution (Oilgae) in deionized (DI) water42,45,75. The environmental conditions were maintained for all reactors with a temperature of 27 °C, pH of 7.0, and aeration (CO2 5% v/v, 0.3-1.0 vvm). The V-shaped reactors had various volumes of 684 mL, 394 mL, 258 mL, 164 mL, and 128 mL and a fixed illumination area of 21.6 cm2. The dual-energy generator had a volume of 500 mL and an area of 45 cm2. Stainless steel reactors with polycarbonate covers were shaken at >80 rpm during the experiment. Visible light transmission of the reactor cover was found to be 77.1%, which was considered for the fitting in Fig. 1d. Autoclaved DI water was injected periodically to compensate for water evaporation.

Analysis

The optical densities (OD = −log10 Transmission) of diluted samples (0.5 mL solution + 2 mL DI water) at 680 nm wavelength were measured using a UV-vis spectrometer (UV-3600 Plus, Shimadzu, Japan) every day and converted to the dry cell weight concentration based on calibration data. The calibration was performed one day after the growth phase ended. The PE was calculated as [(biomass productivity per area) × (heat value per biomass)/(illumination per area)], where the heat value (4.2 kcal g−1) was measured using a calorimeter.

Statistical analysis

Due to the large environmental dependency of microalgal cultivation, we concluded that the representation of the biomass productivities with a single average value and standard deviation may not be trustworthy enough and easily distort the conclusion. Therefore, to avoid the possible misinterpretation and obtain the confidence of the results, the experimental results for semi-continuous cultivation, various environmental conditions, and larger volume reactors are shown with the raw growth curves in SI (Fig. S5).

Conclusion

In this study, the optical inefficiency of microalgal photosynthesis was revealed through advanced system modelling based on both microscopic 3D tomography and macroscopic photosynthesis profile. While the cultivation of microalgae has been mostly studied in the field of bioengineering, we have shown that optical study is a key to further boost the biomass productivity to >100 g m−2 day−1 by making photons penetrate longer distance into the bioreactor. We proposed a V-shaped cultivation as a practical scheme for trapping and diluting sunlight. Our modelling work verified that the V-shaped cultivation can achieve the nearly doubled biomass productivity within the incident angle variation of ±23.5°, compared to the previously proposed photobioreactors of vertically or horizontally installed planar or tubular configurations. Experimentally, we verified that the V-shaped configuration can enhance the biomass productivity from 20.7 g m−2 day−1 to 52.0 g m−2 day−1 under 7.2 kWh m−2 day−1 with an outdoor-simulating environment and such areal productivity was shown to be consistent regardless of the cultivation volume, leading higher volume productivity in shallow reactors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nealson, K. H. & Conrad, P. G. Life: past, present and future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 354, 1923–1939, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1999.0532 (1999).

Liu, C. et al. Nanowire-Bacteria Hybrids for Unassisted Solar Carbon Dioxide Fixation to Value-Added Chemicals. Nano Letters 15, 3634–3639, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b01254 (2015).

Key World Energy Statistics. (Internaional Energy Agency, 2015).

Carrasco, J. M. et al. Power-electronic systems for the grid integration of renewable energy sources: A survey. Ieee Transactions on Industrial Electronics 53, 1002–1016, https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2006.878356 (2006).

Yablonovitch, E. Statistical Ray Optics. Journal of the Optical Society of America 72, 899–907 (1982).

Hoffert, M. I. et al. Advanced technology paths to global climate stability: Energy for a greenhouse planet. Science 298, 981–987, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072357 (2002).

Blaabjerg, F., Teodorescu, R., Liserre, M. & Timbus, A. V. Overview of control and grid synchronization for distributed power generation systems. Ieee Transactions on Industrial Electronics 53, 1398–1409, https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2006.881997 (2006).

International Energy Outlook. (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2013).

Brienen, R. J. W. et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 519, 344−+, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14283 (2015).

Phillips, O. L. et al. Drought Sensitivity of the Amazon Rainforest. Science 323, 1344–1347, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1164033 (2009).

Pan, Y. D. et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 333, 988–993, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201609 (2011).

Amer, L., Adhikari, B. & Pellegrino, J. Technoeconomic analysis of five microalgae-to-biofuels processes of varying complexity. Bioresource Technology 102, 9350–9359, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.08.010 (2011).

Suali, E. & Sarbatly, R. Conversion of microalgae to biofuel. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 16, 4316–4342, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.03.047 (2012).

Mata, T. M., Martins, A. A. & Caetano, N. S. Microalgae for biodiesel production and other applications: A review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 14, 217–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2009.07.020 (2010).

Davis, R., Markham, J. & Humbird, D. Process Design and Economics for the Production of Algal Biomass: Algal Biomass Production in Open Pond Systems and Processing Through Dewatering for Downstream Conversion. (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2016).

Xue, S., Zhang, Q., Wu, X., Yan, C. & Cong, W. A novel photobioreactor structure using optical fibers as inner light source to fulfill flashing light effects of microalgae. Bioresource Technology 138, 141–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.156 (2013).

Pires, J. C. M., Alvim-Ferraz, M. C. M., Martins, F. G. & Simoes, M. Carbon dioxide capture from flue gases using microalgae: Engineering aspects and biorefinery concept. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 16, 3043–3053, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.02.055 (2012).

Zijffers, J. W. F. et al. Maximum Photosynthetic Yield of Green Microalgae in Photobioreactors. Marine Biotechnology 12, 708–718, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-010-9258-2 (2010).

Sun, Y. H., Huang, Y., Liao, Q., Fu, Q. & Zhu, X. Enhancement of microalgae production by embedding hollow light guides to a flat-plate photobioreactor. Bioresource Technology 207, 31–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.01.136 (2016).

Dye, D., Muhs, J., Wood, B. & Sims, R. Design and Performance of a Solar Photobioreactor Utilizing Spatial Light Dilution. Journal of Solar Energy Engineering-Transactions of the Asme 133, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4003419 (2011).

Ahsan, S. S., Pereyra, B., Jung, E. E. & Erickson, D. Engineered surface scatterers in edge-lit slab waveguides to improve light delivery in algae cultivation. Opt. Express 22, A1526–A1537, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.0a1526 (2014).

Guo, C. L. et al. Enhancement of photo-hydrogen production in a biofilm photobioreactor using optical fiber with additional rough surface. Bioresource Technology 102, 8507–8513, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.04.075 (2011).

Nyberg, M., Heidorn, T. & Lindblad, P. Hydrogen production by the engineered cyanobacterial strain Nostoc PCC 7120 ΔhupW examined in a flat panel photobioreactor system. J.Biotechnol. 215, 35–43 (2015).

Cheng-Wu, Z., Zmora, O., Kopel, R. & Richmond, A. An industrial-size flat plate glass reactor for mass production of Nannochloropsis sp. Aquaculture 195, 35–49 (2001).

Naumann, T., Cebi, Z., Podola, B. & Melkonian, M. Growing microalgae as aquaculture feeds on twin-layers: a novel solid-state photobioreactor. J. Appl. Phycol. 25, 1413–1420 (2013).

Liu, T. et al. Attached cultivation technology of microalgae for efficient biomass feedstock production. Bioresour. Technol. 127, 216–222 (2013).

Tredici, M. R. & Zittelli, G. C. Efficiency of sunlight utilization: Tubular versus flat photobioreactors. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 57, 187–197, doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19980120)57:2<187::aid-bit7>3.0.co;2-j (1998).

Carlozzi, P. Dilution of solar radiation through “culture” lamination in photobioreactor rows facing South-North: A way to improve the efficiency of light utilization by cyanobacteria (Arthrospira platensis). Biotechnology and Bioengineering 81, 305–315, https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.10478 (2003).

Kumar, K., Dasgupta, C., Nayak, B., Lindblad, P. & Das, D. Development of suitable photobioreactors for CO2 sequestration addressing global warming using green algae and cyanobacteria. Bioresource Technology 102, 4945–4953 (2011).

Dasgupta, C. et al. Recent trends on the development of photobiological processes and photobioreactors for the improvement of hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 35, 10218–10238 (2010).

Molina, E., Fernandez, J., Acien, F. G. & Chisti, Y. Tubular photobioreactor design for algal cultures. J. Biotechnol. 92, 113–131 (2001).

Hall, D. O., Fernandez, F. G. A., Guerrero, E. C., Rao, K. K. & Grima, E. M. Outdoor helical tubular photobioreactors for microalgal production: modelling of fluid dynamics and mass transfer and assessment of biomass productivity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 82(1), 62–73 (2003).

Travieso, L. et al. A helical tubular photobioreactor producing Spirulina in a semicontinuous mode. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 47, 151–155 (2001).

Woerlee, G. F., Elmore, S. & Wubbolts, F. E. Photo bioreactor with light distributor and method for the production of a photosynthetic culture. US patent US8809041 B2 (2008).

Levesque, M. Sun tracking light distributor system having a v-shaped light distribution channel. US patent US20130323713 A1 (2013).

Posten, C., Jacobi, A., Steinweg, C., Lehr, F. & Rosello, R. Photobioreactor. EP 2388310 A1 (2011).

Hsieh, C. H. & Wu, W. T. A novel photobioreactor with transparent rectangular chambers for cultivation of microalgae. Biochemical Engineering Journal 46, 300–305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2009.06.004 (2009).

Prokop, A., Quinn, M. F., Fekri, M., Murad, M. & Ahmed, S. A. Spectral shifting by dyes to enhance algae growth. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 26, 1313–1322, https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.260261108 (1984).

Mohsenpour, S. F., Richards, B. & Willoughby, N. Spectral conversion of light for enhanced microalgae growth rates and photosynthetic pigment production. Bioresource Technology 125, 75–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.08.072 (2012).

Wondraczek, L. et al. Solar spectral conversion for improving the photosynthetic activity in algae reactors. Nature Communications 4, 2047, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3047 (2013).

Mohsenpour, S. F. & Willoughby, N. Luminescent photobioreactor design for improved algal growth and photosynthetic pigment production through spectral conversion of light. Bioresource Technology 142, 147–153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.05.024 (2013).

Seo, Y. H., Cho, C., Lee, J.-Y. & Han, J.-I. Enhancement of growth and lipid production from microalgae using fluorescent paint under the solar radiation. Bioresource Technology 173, 193–197, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.012 (2014).

Amrei, H. D., Nasernejad, B., Ranjbar, R. & Rastegar, S. An integrated wavelength-shifting strategy for enhancement of microalgal growth rate in PMMA- and polycarbonate-based photobioreactors. European Journal of Phycology 49, 324–331, https://doi.org/10.1080/09670262.2014.919030 (2014).

Wondraczek, L., Tyystjarvi, E., Mendez-Ramos, J., Muller, F. A. & Zhang, Q. Y. Shifting the Sun: Solar Spectral Conversion and Extrinsic Sensitization in Natural and Artificial Photosynthesis. Advanced Science 2, https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201500218 (2015).

Seo, Y. H., Lee, Y., Jeon, D. Y. & Han, J.-I. Enhancing the light utilization efficiency of microalgae using organic dyes. Bioresource Technology 181, 355–359, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.01.031 (2015).

Amrei, H. D., Ranjbar, R., Rastegar, S., Nasernejad, B. & Nejadebrahim, A. Using fluorescent material for enhancing microalgae growth rate in photobioreactors. Journal of Applied Phycology 27, 67–74, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-014-0305-7 (2015).

Baly, E. C. C. The kinetics of photosynthesis. Proc. R. Soc. London Sen B 117, 218–239 (1935).

Monod, J. La technique de culture continue. Theoretic and application. Ann. Inst. Pasteur 79, 390–410 (1950).

Jassby, A. D. & Platt, T. Mathematical formulation of relationship between photosynthesis and light for phytoplankton. Limnology and Oceanography 21, 540–547 (1976).

Platt, T. & Jassby, A. D. Relationship between photosynthesis and light for natural assemblages of coastal marine-phytoplankton. Journal of Phycology 12, 421–430, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3646.1976.00421.x (1976).

Litchman, E., Steiner, D. & Bossard, P. Photosynthetic and growth responses of three freshwater algae to phosphorus limitation and daylength. Freshwater Biology 48, 2141–2148, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01157.x (2003).

Geider, R. J., MacIntyre, H. L. & Kana, T. M. A dynamic regulatory model of phytoplanktonic acclimation to light, nutrients, and temperature. Limnology and Oceanography 43, 679–694 (1998).

MacIntyre, H. L., Kana, T. M., Anning, T. & Geider, R. J. Photoacclimation of photosynthesis irradiance response curves and photosynthetic pigments in microalgae and cyanobacteria. Journal of Phycology 38, 17–38, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1529-8817.2002.00094.x (2002).

Marcelis, L. F. M., Heuvelink, E. & Goudriaan, J. Modelling biomass production and yield of horticultural crops: a review. Scientia Horticulturae 74, 83–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4238(98)00083-1 (1998).

Pruvost, J., Legrand, J., Legentilhomme, P. & Muller-Feuga, A. Simulation of microalgae growth in limiting light conditions: Flow effect. Aiche Journal 48, 1109–1120, https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690480520 (2002).

Walker, R. A., Hallock, P., Torres, J. J. & Vargo, G. A. Photosynthesis and respiration in five species of benthic foraminifera that host algal endosymbionts. Journal of Foraminiferal Research 41, 314–325, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsjfr.41.4.314 (2011).

Kim, K. et al. High-resolution three-dimensional imaging of red blood cells parasitized by Plasmodium falciparum and in situ hemozoin crystals using optical diffraction tomography. Journal of Biomedical Optics 19, 011005–011005, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.jbo.19.1.011005 (2014).

Kim, K. et al. Optical diffraction tomography techniques for the study of cell pathophysiology. Journal of Biomedical Photonics & Engineering 2, 020201 (2016).

Pilon, L. & Kandilian, R. In Advances in Chemical Engineering Vol. 48 (ed Jack Legrand) 107–149 (Academic Press, 2016).

Rochatte, V. et al. Radiative transfer approach using Monte Carlo Method for actinometry in complex geometry and its application to Reinecke salt photodissociation within innovative pilot-scale photo(bio)reactors. Chemical Engineering Journal 308, 940–953, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2016.08.112 (2017).

Heinrich, J. M., Niizawa, I., Botta, F. A., Trombert, A. R. & Irazoqui, H. A. Analysis and Design of Photobioreactors for Microalgae Production I: Method and Parameters for Radiation Field Simulation. Photochemistry and Photobiology 88, 938–951, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2012.01141.x (2012).

Ooms, M. D., Dinh, C. T., Sargent, E. H. & Sinton, D. Photon management for augmented photosynthesis. Nature Communications 7, 12699, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12699 (2016).

de Mooij, T., de Vries, G., Latsos, C., Wijffels, R. H. & Janssen, M. Impact of light color on photobioreactor productivity. Algal Research-Biomass Biofuels and Bioproducts 15, 32–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2016.01.015 (2016).

Melis, A. Solar energy conversion efficiencies in photosynthesis: Minimizing the chlorophyll antennae to maximize efficiency. Plant Science 177, 272–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.06.005 (2009).

Ley, A. C. & Mauzerall, D. C. Absolute absorption cross-sections for photosystem-ii and the minimum quantum requirement for photosynthesis in chlorella-vulgaris. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 680, 95–106, https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2728(82)90320-6 (1982).

Cho, C. et al. Random and V-groove texturing for efficient light trapping in organic photovoltaic cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 115, 36–41 (2013).

Cho, C. & Lee, J. Y. Multi-scale and angular analysis of ray-optical light trapping schemes in thin-film solar cells: Micro lens array, V-shaped configuration, and double parabolic trapper. Opt. Express 21, A276–A284 (2013).

Kang, J., Cho, C. & Lee, J.-Y. Design of asymmetrically textured structure for efficient light trapping in building-integrated photovoltaics. Organic Electronics 26, 61–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgel.2015.07.021 (2015).

Cho, C. et al. Toward Perfect Light Trapping in Thin-Film Photovoltaic Cells: Full Utilization of the Dual Characteristics of Light. Advanced Optical Materials 3, 1697–1702, https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201500471 (2015).

Zijffers, J. W. F., Janssen, M., Tramper, J. & Wijffels, R. H. Design process of an area-efficient photobioreactor. Marine Biotechnology 10, 404–415, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-007-9077-2 (2008).

Kliphuis, A. M. J. et al. Photosynthetic Efficiency of Chlorella sorokiniana in a Turbulently Mixed Short Light-Path Photobioreactor. Biotechnology Progress 26, 687–696, https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.379 (2010).

Cuaresma, M., Janssen, M., Vilchez, C. & Wijffels, R. H. Productivity of Chlorella sorokiniana in a Short Light-Path (SLP) Panel Photobioreactor Under High Irradiance. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 104, 352–359, https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.22394 (2009).

Rim, S. B., Zhao, S., Scully, S. R., McGehee, M. D. & Peumans, P. An effective light trapping configuration for thin-film solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 243501, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2789677 (2007).

Tvingstedt, K., Andersson, V., Zhang, F. & Inganas, O. Folded reflective tandem polymer solar cell doubles efficiency. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 123514, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2789393 (2007).

Rippka, R., Deruelles, J., Waterbury, J. B., Herdman, M. & Stanier, R. Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. Journal of General Microbiology 111, 1–61 (1979).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Graphene Materials and Components Development Program of MOTIE/KEIT (10044412), a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP, NRF-2015M1A2A2057509), and the Advanced Biomass R&D Center (ABC) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2011-0031348). We also gratefully acknowledge support from the New & Renewable Energy Core Technology Program of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and a financial grant from the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (No. 20163010012200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. Cho, J. Han and J. Lee conceived and designed the experiments and prepared the manuscript. C. Cho established the modelling method, performed the simulations, and conducted the cultivation. K. Nam and Y. Seo assisted with the experiments by preparing the samples and characterizing the cells. K. Kim and Y. Park performed the optical diffraction tomography. All of the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, C., Nam, K., Seo, Y.H. et al. Study of Optical Configurations for Multiple Enhancement of Microalgal Biomass Production. Sci Rep 9, 1723 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38118-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38118-w

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.