Abstract

Tuberculosis is a multifactorial bacterial disease, which can be modeled in the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Abdominal cavity infection with Mycobacterium marinum, a close relative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, leads to a granulomatous disease in adult zebrafish, which replicates the different phases of human tuberculosis, including primary infection, latency and spontaneous reactivation. Here, we have carried out a transcriptional analysis of zebrafish challenged with low-dose of M. marinum, and identified intelectin 3 (itln3) among the highly up-regulated genes. In order to clarify the in vivo significance of Itln3 in immunity, we created nonsense itln3 mutant zebrafish by CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis and analyzed the outcome of M. marinum infection in both zebrafish embryos and adult fish. The lack of functional itln3 did not affect survival or the mycobacterial burden in the zebrafish. Furthermore, embryonic survival was not affected when another mycobacterial challenge responsive intelectin, itln1, was silenced using morpholinos either in the WT or itln3 mutant fish. In addition, M. marinum infection in dexamethasone-treated adult zebrafish, which have lowered lymphocyte counts, resulted in similar bacterial burden in both WT fish and homozygous itln3 mutants. Collectively, although itln3 expression is induced upon M. marinum infection in zebrafish, it is dispensable for protective mycobacterial immune response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis is an epidemic multifactorial disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis1. The susceptibility to tuberculosis depends on the M. tuberculosis strain and on a number of host-related factors such as environmental conditions, other underlying diseases as well as genetic variation2,3,4. Critical genes of the adaptive immunity required for the mycobacterial immune response such as interferon gamma (IFNG)5,6 and interleukin 12 (IL12)7,8 were identified already in the 1980’s and 1990’s, respectively. The importance of these genes has later been verified in human tuberculosis patients9 and by using experimental gene knockout mouse models of tuberculosis10,11,12,13. More recently, pattern recognition receptor (PRR) gene polymorphisms of Toll-like receptors (TLRs)14,15,16 and C-type lectins17,18, have been associated with M. tuberculosis susceptibility, delineating also the central role of the innate immunity in controlling the mycobacterial infection.

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins important for numerous biological processes such as intracellular glycoprotein secretion, leukocyte trafficking and microbial recognition19,20. Consequently, lectins act as recognition molecules inside cells, on the cell surface and in extracellular fluids20. Intelectins (ITLNs) are a distinct family of lectins, which were first identified in Xenopus laevis21 and were later found in a number of chordates including human, mouse and zebrafish (Danio rerio)22,23,24,25. Although ITLN function has been linked to a number of processes such as iron absorption26, metabolic disorders27 as well as cancer development28,29, their exact biological functions are elusive. Suggesting a role for ITLNs in the immune response, itln gene expression is highly up-regulated upon a bacterial infection in fish25,30,31,32. Moreover, human ITLN1 (also known as Omentin) has been shown to bind to the Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)33, and more specifically to exocyclic 1,2-diol glycan epitopes that are expressed selectively on microbial surfaces34.

The importance of ITLNs for immunity in vivo, however, is less clear. Previously, Voehringer et al., used transgenic mice with lung-specific ITLN1 and ITLN2 over-expression to study the effects of these proteins in the mouse infection models of the parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and the M. tuberculosis bacterium35. In these settings, the authors could not detect enhanced pathogen clearance in the Itln transgenic mice. In contrast, a so called “natural deletion” of the Itln2 gene has been previously associated with a higher susceptibility against the parasite Trichinella spiralis in a C57BL/10 mouse strain36. Recently, an Itln1 knockout mouse strain was created to study inflammatory bone diseases37. In the aforementioned study, the lack of Itln1 was associated with a proinflammatory phenotype characterized by elevated TNF and IL6 levels in bone tissue and in serum, and was shown to result in osteoporosis37.

The genome of the zebrafish was assembled for the first time in 2002 and the prevalent 11th assembly (GRCz11) is an invaluable tool for research using zebrafish as a disease model38. Over 70% of human genes have at least one zebrafish orthologue and for this reason, the zebrafish immune system is highly similar compared to humans38. In fact, most of the human immune cell populations such as T- and B-cells39,40,41, neutrophils and macrophages42, dendritic cells43 as well as the complement system44 and immunoglobulins45,46, are found in the zebrafish. Importantly, zebrafish can be modified genetically with the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated 9 (Cas9) mutagenesis47,48, which allows disease modeling using reverse genetics, although some genes appear difficult to target successfully49.

A Mycobacterium marinum infection of zebrafish is nowadays a commonly used model for studying tuberculosis in both larvae and adult fish50,51. Compared to several other tuberculosis models, the mycobacterial model of zebrafish is considered safe, cost-effective and ethical52,53. More importantly, M. marinum is closely related to M. tuberculosis, and the two bacterial species have comparable pathogenic characteristics in the natural hosts; macrophage mediated intracellular multiplication as well as the formation of granuloma structures54,55,56. The larval model enables studying specifically the innate immunity57,58, whereas the adult zebrafish model allows studying also components of the adaptive immune system in both an acute mycobacterial infection59 as well as during mycobacterial latency56,60.

In order to identify candidate genes associated with the host response against mycobacteria, we conducted a gene expression microarray in M. marinum infected adult zebrafish. Here, we identified a zebrafish ITLN orthologue itln3 among the genes that were most induced upon infection. In order to gain more insights into the function of ITLNs, we used CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis to create knockout itln3 mutant zebrafish lines, and used the zebrafish M. marinum infection model to determine the in vivo significance of Itln3 in a mycobacterial infection.

Results

Genome-wide gene expression microarray analysis of M. marinum infected adult zebrafish

In order to identify genes involved in the host immune response against mycobacteria, we used the zebrafish M. marinum infection model and conducted a genome-wide gene expression analysis using the microarray platform. To this end, we infected wild-type (WT) AB zebrafish with M. marinum (20 CFU; SD 6 CFU) and isolated their organ blocks (includes all the organs of the abdominal cavity) for a transcriptomic analysis at 14 days post infection (dpi). From a total of 43603 probes used in the analysis, we found 93 probes, corresponding to 70 genes, that were up-regulated and 26 probes, corresponding to 21 genes, that were down-regulated (log2 fold change >\(|3|\)) compared to the mock-treated (PBS) controls (Supplementary Table 1). Further evaluation of the up-regulated probes with a GOrilla gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis61,62 revealed 22 enriched (p < 0.001) processes including response to carbohydrates (GO:0009743), cholesterol homeostasis (GO:0042632) and antigen processing and presentation (GO:0019882) (Supplementary Table 2). Among the up-regulated genes we found five genes; si:busm1-194e12.11 (mhc2 family gene), arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase b, tandem duplicate 3 (alox5b.3), zgc:113912 (mhc2 family gene), CD59 molecule (cd59) and si:busm1-194e12.12 (mhc2 family gene) with well-known immunological functions in antigen processing, inflammation and in the regulation of the complement system (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table 1). Of the 21 down-regulated genes, five were associated with the immune response; CD58 molecule (cd58), myeloid-specific peroxidase (mpx), complement factor b-like (cfbl), immunoresponsive gene 1, like (irg1l) and si:busm1-266f07.1 (mhc2 family gene) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, approximately 38% of the up-regulated probes i.e. parvalbumin 1 (pvalb1), alpha-tropomyosin (tpma), troponin I, skeletal, fast 2b, tandem duplicate 2 (tnni2b.2) and myosin, heavy polypeptide 1.1 (myhz1.1) were related to muscle associated biological processes including muscle contraction (GO:0006936), muscle system process (GO:0003012) and myofibril assembly (GO:0030239) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The GO-analysis of the down-regulated probes also showed a significant enrichment of another 22 processes including response to external biotic stimulus (GO: 0043207) and cholesterol biosynthetic process (GO:0006695) and immunological processes, such as response to other organism (GO:0051707), response to bacterium (GO:0009617) and the induction of bacterial agglutination (GO:0043152) (Supplementary Table 2).

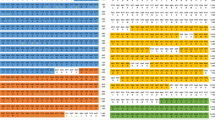

Zebrafish intelectin genes are differentially expressed upon M. marinum infection. (A) A genome-wide gene expression microarray was conducted in adult WT AB zebrafish injected with M. marinum (20 CFU; SD 6 CFU) (n = 2) or PBS (n = 3). Average numerical results (log2) for each probe in both infected fish (y-axis) and PBS controls (x-axis) are shown. Up- and down-regulated transcripts (log2 fold change \(|3|\)) in the organ blocks are shown in grey, and the common immunological genes are annotated. Two itln3 probes as well as itln2 and itln2-like probes are highlighted. (B–E) The expression of zebrafish itln genes (itln1, itln2, itln2-like and itln3) was measured with qPCR in the organ blocks of the M. marinum infected (6 CFU; SD 3 CFU) and PBS injected adult WT e46 zebrafish at 1 (n = 12 and n = 4, respectively) and 6 dpi (n = 12 and n = 8, respectively) as well as 4 (n = 12 and n = 11, respectively) and 9 wpi (n = 12 and n = 10, respectively). (F–I) The expression of itln1, itln2, itln2-like and itln3 was determined with qPCR in the M. marinum (39 CFU; SD 47 CFU) infected WT AB embryos (n = 5 at all timepoints) and in PBS injected controls (n = 5 at all timepoints) at 1–7 dpi. Note the different scales of the y axes in B-I. Gene expressions were normalized to eef1a1l1 expression and target genes were run once in the qPCR analyses. A two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used in the statistical comparison of differences in B–I.

Mycobacterial infection up-regulates itln3 expression in both zebrafish embryos and adult fish

Previous studies in several animal models have shown the expression of the Intelectin (ITLN) gene to be induced upon a bacterial infection25,30,32. Accordingly, the expression of the zebrafish itln3 (ENSDARG00000003523) was increased on average 3.3-fold (log2 change) upon a M. marinum infection in our microarray analysis (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, two other itln genes; itln2 (ENSDARG00000036084) and itln2-like (ENSDARG00000093796) were down-regulated compared to the PBS controls (−3.5 and −3.2 log2 fold change, respectively) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table 1), suggesting a diverse regulation of itln genes in the M. marinum infected zebrafish. Since both ENSDARG00000036084 and ENSDARG00000093796 share the same gene name, itln2, in Ensembl genome browser, ENSDARG00000093796 is referred to as itln2-like throughout the text.

To confirm the differential expression pattern of the itln family members in the zebrafish mycobacterial infection and to study the kinetics of the host response more carefully, we analyzed itln1 (ENSDARG00000007534), itln2, itln2-like and itln3 gene expression from the abdominal cavity organ blocks of M. marinum infected (6 CFU; SD 3 CFU) WT e46 background adult zebrafish with qPCR at 1 and 6 dpi, as well as at 4 and 9 weeks post infection (wpi) (Fig. 1B–E). In line with our microarray data, itln3 was significantly induced at 4 wpi (3.8-fold, P = 0.002) and 9 wpi (5.9-fold, P = 0.003) (Fig. 1E), whereas itln2 was down-regulated compared to the PBS controls both at 6 dpi (0.3-fold, P = 0.019) and 4 wpi (0.2-fold, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1C). No significant differences in the relative mRNA expression levels of the itln1 (Fig. 1B) or itln2-like (Fig. 1D) genes were observed between infected and the PBS injected adult fish at any of the measured time points.

Next, we infected WT AB zebrafish embryos with mycobacteria and performed an expression analysis of the itln genes by qPCR. Here, M. marinum (39 CFU; SD 47 CFU) was microinjected into the yolk sac of the embryos and the gene expression was quantified daily between 1 and 7 dpi (Fig. 1F–I). In the mycobacteria infected embryos we detected the up-regulation of both itln1 (1.8 to 6.4-fold, P = 0.008–0.016) (Fig. 1F) and itln3 (1.8 to 111.4-fold, P = 0.008–0.032) (Fig. 1I) starting at 2 dpi and continuing until 7 dpi, as well as the induction of itln2 at 7 dpi (21.6-fold, P = 0.008) (Fig. 1G) and itln2-like (Fig. 1H) between 4 and 7 dpi (20.7 to 76.1-fold, P = 0.008–0.032) compared to the PBS controls. Also, in line with previous reports suggesting that other infectious diseases up-regulate ITLN expression, a significant induction of itln3 expression (8.4-fold at 7hpi; 11.8-fold at 18hpi; 5.5-fold at 24hpi; 4.4-fold at 48hpi, P = 0.002 in all comparisons) was observed in Streptococcus pneumoniae (T4 serotype) infected (296 CFU; SD 32 CFU) embryos (Supplementary Figure 1).

In order to understand the infection-inducible nature of the zebrafish itln genes at steady state, we quantified the relative mRNA levels of itln1, itln2, itln2-like and itln3 in the liver, spleen, kidney and intestine of unchallenged WT e46 zebrafish by qPCR (Fig. 2A–D). Here, we found that itln2 expression was restricted to the intestine (Fig. 2B), whereas itln3 showed the highest relative expression in the liver and the highest overall expression compared to the housekeeping gene (eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1, like 1; eef1a1l1) (Fig. 2D). Conversely, itln1 was expressed in all of the studied tissues with the second highest overall expression levels (Fig. 2A), while itln2-like was primarily expressed in the zebrafish kidney and the intestine (Fig. 2C). These results are in line with a previous qPCR analysis of the itln gene family members in unchallenged adult zebrafish25.

Expression of zebrafish itln genes in adult zebrafish tissues. Relative expression of (A) itln1, (B) itln2, (C) itln2-like and (D) itln3 was measured with qPCR in the uninfected adult WT e46 zebrafish liver (n = 10), spleen (n = 10), kidney (n = 10) and the intestine (n = 10). Note the different scales of the y axes. Gene expressions were normalized to eef1a1l1 expression and target genes were run once in the qPCR analyses.

Creating itln3 mutant zebrafish using CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis

The type II CRISPR/Cas system is an invaluable technology for targeted genome editing63,64, and to date it has been utilized in a number of model organisms. We and others have used the CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis method successfully in the zebrafish47,49,65,66. Here, we used the CRISPR/Cas9 method to create zebrafish carrying nonsense itln3 mutations for our in vivo studies (Fig. 3). To this end, we identified a functional gRNA targeting the second exon of the itln3 gene with an average mutagenesis efficiency of 39.5% (Fig. 3A,B). After an outcross of parental mutation carriers (F0-generation) with WT TL zebrafish, we observed two germ-line transmitted frameshift mutations in the F1-progeny corresponding to a total loss of five base pairs (−5 bp; loss of GCATC) and to a total gain of eight base pairs (+8 bp; loss of GGAGCATC and gain of TGCTAGGTAAGTATCA) at the target loci (Fig. 3C). Analyses with the Translate tool (Expasy; SIB, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics)67 of both the −5 bp and +8 bp mutations confirmed the disrupted reading frames from amino acids 47 and 45 onwards resulting in premature stop-codons after 79 and 71 amino acids, respectively (Fig. 3C). These two different itln3 null mutant zebrafish lines were named itln3uta145 (−5 bp mutation) and itln3uta148 (+8 bp mutation). qPCR analysis of uninjected and M. marinum infected (422 CFU; SD 221 CFU, 2 wpi) adult zebrafish revealed diminished itln3 transcript levels in the homozygous itln3uta145/uta145 (residual expression less than 1%, P < 0.001) and itln3uta148/uta148 mutants (residual expression less than 0.1%, P < 0.001) compared to the WT controls (Supplementary Figure 2), suggesting that the indel-mutations lead to the nonsense-mediated RNA decay of the mutant mRNAs68. Furthermore, the inheritance of the mutations followed Mendelian ratios for both of the mutant lines, and the homozygous itln3uta145/uta145 and itln3uta148/uta148 mutants did not show any developmental defects nor phenotypical differences compared to their WT siblings (Supplementary Figure 3).

Generation of itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 mutant zebrafish lines using CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis. (A) An appropriate guide RNA (gRNA) target site was identified in the second exon of itln3. (B) 2.5% agarose TAE gel electrophoresis was performed to evaluate occurrence of target site mutations in zebrafish. The in vivo CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis efficiency was estimated with the T7EI assay in the gRNA and Cas9 mRNA injected embryos. The size of the uninjected WT control PCR product is 210 bp, whereas the PCR products of the mutated embryos are partially cleaved at the target site. The cleavage efficiency was calculated from the band intensities and the mutagenesis efficiency calculated according to the following formula: % mutagenesis = 100 × (1 – (1- fraction of cleavage)1/2)64. GeneRuler 50 bp DNA Ladder (#SM0373, Thermo Fischer Scientific) was used as a molecular weight marker (MW). Gel image is cropped to exclude portions that do not contain experimental samples. (C) gRNA target sites were sequenced from F1-generation mutant zebrafish and two frameshift mutations (-5 bp deletion, itln3uta145 and +8 bp insertion, itln3uta148) detected, leading to truncated protein products of 79 and 71 amino acids, respectively.

Nonsense mutation in itln3 does not affect host resistance against M. marinum in zebrafish embryos

The up-regulation of the expression of the itln3 gene in a M. marinum infection suggests a possible role for Itln3 in the host immunity against mycobacterial infections. To test if the resistance towards a mycobacterial infection is altered in homozygous itln3 mutant embryos, we first infected M. marinum (40 CFU; SD 30 CFU) into the yolk sac of the ungenotyped F2-progeny of heterozygous itln3uta145/+ and itln3uta148/+ zebrafish and followed their survival until 7 days post fertilization (dpf) (Fig. 4A,B). Post-experiment genotyping revealed an average survival of 47% in the itln3uta145 background embryos and 48% in the embryos with the itln3uta148 background. However, any significant differences in the survival between the homozygous and heterozygous itln3 mutants or WT fish could not be observed in either itln3uta145 (Fig. 4A) or itln3uta148 fish lines (Fig. 4B) before 7 dpi (7 dpf). Next, we quantified the mycobacterial burden in the embryos that had survived by qPCR using primers for M. marinum internal transcribed spacer (MMITS)56 (Fig. 4C). The M. marinum quantification revealed bacterial copy number medians (log10) of 4.18 and 4.15 in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA in the itln3uta145 and itln3uta145 WT groups, respectively. Comparably, heterozygous itln3uta145/+ and itln3uta148/+ fish had copy number medians of 4.02 and 4.22 (in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA, log10), respectively, and the homozygous itln3uta145/uta145 and itln3uta148/uta148 mutants 3.53 and 4.25 (in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA, log10). Thus, there were no statistically significant differences in the mycobacterial burdens between the different genotypes in neither itln3uta145 nor itln3uta148 zebrafish.

The lack of itln3 does not affect the survival or the mycobacterial burden of M. marinum infected zebrafish embryos. (A,B) M. marinum (40 CFU; SD 30 CFU) was injected into the yolk sac of the WT (itln3uta145) (n = 31), itln3uta145/+ (n = 74), itln3uta145/uta145 (n = 22), WT (itln3uta148) (n = 19), itln3uta148/+ (n = 27) and itln3uta148/uta148 (n = 16) zebrafish embryos at 0 dpf and the survival recorded until 7 dpi. A log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for the statistical comparison of differences. The data was collected from a single experiment. (C) Mycobacterial burden was measured by qPCR from the yolk sac infected WT (itln3uta145) (n = 17), itln3uta145/+ (n = 32), itln3uta145/uta145 (n = 10), WT (itln3uta148) (n = 9), itln3uta148/+ (n = 15) and itln3uta148/uta148 (n = 7) embryos that were alive at 7 dpi. (D) M. marinum (46 CFU; SD 31 CFU) was injected into the blood circulation valley of the WT (itln3uta145) (n = 29), itln3uta145/+ (n = 77), itln3uta145/uta145 (n = 36), WT (itln3uta148) (n = 31), itln3uta148/+ (n = 57) and itln3uta148/uta148 (n = 19) zebrafish embryos at 2 dpf and the M. marinum burden quantified at 5 dpi. Bacterial load is represented in panels C and D as bacterial copies (log10) in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA. A two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used in the statistical comparison of differences in C and D.

The site of the bacterial injection can affect the immune response in the embryos50. Therefore, we next treated the ungenotyped F2-progeny of itln3uta145/+ and itln3uta148/+ zebrafish by injecting M. marinum into the blood circulation valley of 2-day-old embryos. In these fish, the M. marinum infection (46 CFU; SD 31 CFU) was not able to cause any mortality prior to the experimental end-point of 5 dpi (7 dpf). However, this allowed us to quantify the M. marinum burden in all of the infected embryos at the end-point (Fig. 4D). Here, the bacterial copy number medians (log10) in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA were 3.61 (WT itln3uta145), 3.83 (WT itln3uta148), 3.63 (itln3uta145/+), 3.77 (itln3uta148/+), 3.75 (itln3uta145/uta145) and 3.79 (itln3uta148/uta148). Similarly to the yolk sac infection, mycobacterial quantification did not reveal any differences between the individuals of the different genotypes in either the itln3uta145 or the itln3uta148 zebrafish background. Noteworthy, we also infected the ungenotyped F2-progeny of itln3uta145/+ and itln3uta148/+ zebrafish with S. pneumoniae (serotypes 1 and T4, blood circulation valley infection at 2 dpf) and followed the survival of the fish to 5 dpi69. There was no difference between WT embryos and the itln3 mutants (Supplementary Figure 1).

Deleterious mutations may lead to genetic compensation, which in turn can affect the observed phenotype in gene knockout models70. To address this, we used a morpholino-oligonucleotide to silence itln1 in our itln3 mutant zebrafish together with the yolk sac mycobacterial infection of zebrafish embryos. In order to ensure efficient termination of translation in all of the four zebrafish itln1 transcripts, we targeted the second exon (E2) of the gene with a splice-blocking (SB) morpholino (Fig. 5A). In our initial SB morpholino titration experiments, 2.8 ng of itln1-blocking morpholino did not reveal any adverse effects on the survival or on the phenotype of unchallenged zebrafish embryos within the first 7 dpf. However, lower WT itln1 mRNA levels were observed in the SB morphants with residual expression of 17.1% at 4 dpi, 21.8% at 5 dpi and 33.9% at 6 dpi compared to the random control (RC) injected embryos (Fig. 5B), demonstrating that this amount of the SB morpholino silences the expression of itln1 efficiently during embryonic development. In addition, detectable itln1 expression levels were observed in the RC morphants already at 1 dpi, whereas in the SB morpholino injected embryos itln1 expression was evident later starting at 2 dpi based on qPCR (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Figure 4). Next, we performed morpholino-M. marinum co-injections (20 CFU; SD 19 CFU) into the yolk sac of the un-genotyped F2-progeny of itln3uta145/+ and itln3uta148/+ zebrafish (Fig. 5C–E) and the F3-progeny of WT itln3uta148 (13 CFU; SD 10 CFU) (Fig. 5C) and followed their survival up to 7 dpi. There were few dying embryos among uninfected embryos upon RC or itln1 morpholino injection (Supplementary Figure 4), whereas the mortality reached 77.8–100% in the morpholino-M. marinum co-injected embryos. Noteworthy, the comparison between the infected RC and SB morpholino injected WT itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 embryos did not show any differences in survival (Fig. 5C). Moreover, inhibiting itln1 expression in homozygous itln3uta145/uta145 and itln3uta148/uta148 mutants lead to a similar mortality compared to the corresponding heterozygous and WT siblings of the same genetic background (Fig. 5D,E), indicating that the simultaneous lack of itln1 and itln3 functionality does not affect mycobacterial resistance in the zebrafish embryo. Consistently, we did not detect any differences in the mRNA levels of itln1, itln2 and itln2-like between the homozygous itln3 mutants and the WT controls either in uninjected (4 dpf) or M. marinum (25 CFU; SD 23 CFU, 4 dpf/4 dpi) infected embryos (Supplementary Figure 5), suggesting that there is no transcriptional compensation by the other studied intelectin gene members in the itln3uta145/uta145 and itln3uta148/uta148 mutant fish. Similarly, no transcriptional compensation by itln1, itln2 or itln2-like was observed in the adult itln3 mutant zebrafish either in steady state or upon M. marinum infection (Supplementary Figure 2).

Morpholino mediated silencing of itln1 expression does not alter the survival of the WT or itln3 knockout zebrafish in a M. marinum infection. (A) A schematic representation of the effects of the morpholino mediated silencing of itln1. A splice site blocking morpholino (SB) was used to prevent the normal splicing event between exon 2 and exon 3 in itln1. Morpholino binding to its target site leads to an alternative splicing event that deletes the start codon containing exon 2 from the transcript. Consequently, this prevents translation of the Itln1 protein. In order to quantify the relative amount of the WT itln1 transcript, qPCR primers were designed to specifically amplify only the WT itln1 mRNA. (B) WT itln1 expression was quantified with qPCR from the itln1 SB morpholino (n = 3) and random control morpholino (RC) injected zebrafish (n = 3) at 1–7 dpf. Gene expression was normalized to eef1a1l1 expression. All samples were run once as technical duplicates. (C–E) Survival of the morpholino and M. marinum (20 CFU; SD 19 or 13 CFU; SD 10 CFU) co-injected embryos were followed until 7 dpi. In panel C, WT (itln3uta145 and itln3uta148) embryos injected with either SB (n = 47 and n = 53, respectively) or RC morpholino (n = 29 and n = 54) are shown, whereas in panels D and E the itln3uta145 background (n = 45–73) and itln3uta148 background embryos (n = 18–35) injected with SB morpholino are depicted, respectively. Note that the SB morpholino injected WT (itln3uta145) embryo group is shown in both C and D panels in order to simplify data representation. The data in panel C was collected from two individual experiments, whereas other data is from a single experiment. A log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for the statistical comparison of differences. MO = morpholino.

Adult itln3 mutant zebrafish have a normal immune response towards a M. marinum infection

In order to test the mycobacterial susceptibility of the itln3 mutants in adult zebrafish, we performed a low-dose (48 CFU; SD 5 CFU) mycobacterial inoculation into the abdominal cavity of the fish and followed their survival for up to 24 wpi (Fig. 6A,B). After the follow-up, an average of 67% of the itln3uta145 background zebrafish had survived, corresponding to 74% of the WT, 73% of the itln3uta145/+ and 59% of the itln3uta145/uta145 fish. In the itln3uta148 background fish, a combined survival percentage of 81% was observed (78% in the WT, 82% in the itln3uta148/+ and 84% in the itln3uta148/uta148 fish). Similarly to the embryonic survival experiments, no statistically significant differences in the survival between the genotypes were observed.

Adult itln3 mutant zebrafish have comparable survival and mycobacterial burden compared to WT fish upon M. marinum infection. (A) The WT (itln3uta145) (n = 38), iltn3uta145/+ (n = 40), iltn3uta145/uta145 (n = 38) and (B) WT (itln3uta148) (n = 38), iltn3uta148/+ (n = 38), iltn3uta148/uta148 (n = 38) zebrafish were infected with M. marinum (48 CFU; SD 5), and their survival followed for 24 weeks. A log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for the statistical comparison of differences. The data was collected from a single experiment. (C,D) The itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 background zebrafish were infected with M. marinum (422 CFU; SD 221 CFU) and bacterial burden (log10) in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA determined at 2 and 4 wpi from the organ blocks (without the kidney). Group sizes at 2 and 4 wpi, respectively, were as follows: WT (itln3uta145) n = 10, n = 8; iltn3uta145/+ n = 12, n = 12; iltn3uta145/uta145 n = 12, n = 12; WT (itln3uta148) n = 9, n = N/A; iltn3uta148/+ n = 9, n = 14 and iltn3uta148/uta148 n = 8, n = 12. All samples were run once. A two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used in the statistical comparison of differences. N/A = no fish available for analysis.

We and others have previously shown that the outcome of a mycobacterial infection in adult zebrafish depends not only on the host genotype but also on the infection dose. While, a so called low-dose inoculate can result in latency and a chronic disease56, a higher dose leads to a fast progressing acute infection59,71. We hypothesized that the effects caused by the lack of Itln3 could be more prominent in an infection with a higher mycobacterial dose. Consequently, we infected WT fish as well as heterozygous and homozygous itln3 mutants from both the itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 backgrounds with a higher M. marinum dose (422 CFU; SD 221 CFU) and quantified the bacterial burden at 2 and 4 wpi (Fig. 6C,D). In these fish, we detected M. marinum copy number medians (log10) of 4.19 (WT itln3uta145), 3.76 (itln3uta145/+), 4.16 (itln3uta145/uta145), 3.69 (WT itln3uta148), 3.73 (itln3uta148/+) and 3.92 (itln3uta148/uta148) in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA at 2 wpi and 4.72 (WT itln3uta145), 4.36 (itln3uta145/+), 4.60 (itln3uta145/uta145), 4.10 (itln3uta148/+) and 3.72 (itln3uta148/uta148) at 4 wpi. Noteworthy, no WT itln3uta148 fish were available at 4wpi for a bacterial quantification. Altogether, these data indicate that the loss of Itln3 function is dispensable for the host resistance against abdominal cavity M. marinum infection in adult zebrafish.

Dexamethasone mediated lymphocyte depletion in itln3 knockout zebrafish does not affect the survival or mycobacterial burden in a M. marinum infection

We have recently published a zebrafish immune-suppression model for mycobacterial reactivation using orally administered dexamethasone60. The dexamethasone treatment decreases the total amount of lymphocytes by an average of 36% (from a relative proportion of 19.3% to 12.4%), and consequently leads to reactivation of the M. marinum infection. In turn, a number of studies have suggested that Itln3 functions in microbial surveillance and therefore in the innate immunity23,24,34. In order to highlight the importance of innate immune mechanisms in the mycobacterial defense, we used the dexamethasone treatment to specifically deplete the lymphocyte population in the adult itln3 mutation carrying zebrafish lines itln3uta145 and itln3uta148, and subsequently infected both WT and homozygous itln3 mutants with M. marinum (47 CFU; SD 4 CFU) (Fig. 7A). Expectedly, our flow cytometric analysis demonstrated a significant decrease in the lymphocyte counts of both WT itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 fish (31.5%, P = 0.002 and 23.7%, P = 0.010, respectively) as well as the itln3uta145/uta145 and itln3uta148/uta148 mutants (31.5% and 40.5%, P < 0.001 in both comparisons) three weeks after initiating the dexamethasone administration at 2 wpi (Fig. 7B–D). In addition, neither the total cell count nor the amount of myeloid cells and blood cell precursors were affected by dexamethasone (Supplementary Figure 6). We did not detect any substantial mortality of either the itln3uta145 or the itln3uta148 mutants or WT fish during the five-week follow-up period. As is shown in the Fig. 7D,E, the bacterial amounts did not differ between the groups; in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA, mycobacterial copy number medians (log10) of 2.60 and 2.65 in WT itln3uta145, 2.55 and 3.10 in itln3uta145/uta145, 2.87 and 2.43 in WT itln3uta148 and 2.25 and 2.91 in itln3uta148/uta148 zebrafish were observed at 2 and 4 wpi, respectively.

Dexamethasone mediated immunosuppression does not alter the survival of itln3 deficient zebrafish in a mycobacterial infection. (A) A schematic representation of the performed experiment. M. marinum inoculate used in the infections were 47 CFU (SD 4 CFU). (B) Representative flow cytometry plots in WT (itln3uta148) zebrafish at -1 wpi and 2 wpi used for quantifying lymphocyte, myeloid cell and precursor cell populations. FSC = forward scatter, SSC = side scatter. (C,D) Lymphocyte fractions of the total cell populations for both WT and itln3 knockout zebrafish at -1 wpi and 2 wpi. Both the itln3uta145 (n = 12 in all groups) and itln3uta148 background fish (n = 8 in all groups) are shown. Blood cell samples were run as technical duplicates. (E,F) M. marinum burden (log10) in 100 ng of zebrafish DNA were measured at 2 wpi and 4 wpi by qPCR in the infected dexamethasone treated zebrafish organ blocks (without the kidney). All bacterial quantification samples were run once. Group sizes at 2 and 4 wpi, respectively, were as follows: WT (itln3uta145) n = 9, n = 8; iltn3uta145/uta145 n = 9, n = 10; WT (itln3uta148) n = 6, n = 9 and iltn3uta148/uta148 n = 7, n = 8. A two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used in the statistical comparison of differences.

In conclusion, our data are in accordance with previous literature on the possible role for itlns in immunity, as the zebrafish itln3 is highly induced in a mycobacterial infection. However, M. marinum infection experiments using both zebrafish embryos and adult fish suggest that itln3 is dispensable for a protective mycobacterial host response. Moreover, itln1 does not seem to compensate for the lack of functional itln3 in the embryonic infection model. Of note, unlike has been reported for human ITLN1, we were unable to demonstrate direct binding of recombinant Itln3 to mycobacteria (or S. pneumoniae or Escherichia coli) in vitro (Supplementary Figure 7), which may explain the nonessential role of Itln3 for zebrafish immunity in our models.

Discussion

The genetics of the host affect the outcome of a M. tuberculosis infection, i.e. the development of active tuberculosis4. Genome-wide expression analyses using microarray and RNA sequencing platforms are important for understanding complicated biological processes such as the host immune defense against pathogens. To date, a handful of transcriptome studies have been done in the zebrafish M. marinum infection model using microarray technology59,72,73, the digital gene expression (DGE) method74 and RNA sequencing75,76,77. Collectively, by using both zebrafish embryos and adult fish, these studies have provided important insights into the innate and adaptive host response against mycobacterial infections.

We used the adult zebrafish M. marinum (ATCC 927) infection model together with a zebrafish gene expression microarray to identify novel candidate genes in a mycobacterial infection. From this data, we identified a total of 91 differentially expressed genes (log2 fold change >\(|3|\)) that were linked to 44 enriched processes, including genes associated with the immune response. Previous studies have shown several genes of the complement system (e.g. complement component c3b, c3b; complement component 6, c6) to be up-regulated in an infection59,72,73,74,76, whereas the expression of some complement associated genes (e.g. complement factor b, cfb; mannose binding lectin, mbl) has been shown to be reduced72,74. In line with previous results, we also saw an induction of cd59 (regulation of membrane attack complex formation) as well as reduced expression of cfbl (component of the C3 convertase). Conversely, although previous transcriptomic studies have shown the induction of genes that are involved in neutrophil and macrophage related functions (e.g. mpx and irg1l)73,76, our data indicated down-regulation of these transcripts in an infection. In summary, the aforementioned similarities and differences between these transcriptomic studies can result from a number of factors including the developmental stage of the host (embryos vs. adult fish), the time points chosen for sample collection, the different outcomes of an infection (chronic vs. acute), the use of different bacterial strains (E11, Mma20 or ATCC 927) and doses, and they can be due to differences in the technical execution of sample preparation and analyses.

Interestingly, circa 38% of the up-regulated probes were related to muscle associated biological processes including muscle contraction (GO:0006936), muscle system process (GO:0003012) and myofibril assembly (GO:0030239). Supporting the relevance of this finding, a genome-wide expression analysis in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster identified several muscle specific genes such as actin88F (Act88F) and tropomycin 2 (Tm2) to be induced after a Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection78. Consistently, the down-regulation of muscle expressed genes (troponin C41C, TpnC41C; glutathione S-Transferase 2, Gst2) was later connected to an increased susceptibility to infection, suggesting an immunological role for muscle tissue79,80. Although the differential expression of muscle specific genes can be indirectly linked to the immune response through the regulation of other physiological functions, as has been also suggested by Chatterjee et al.,81, both mouse and zebrafish muscle tissues have also been reported to control the expression of inflammatory cytokine genes (Tnfa and Il6) upon activation of the immune response82,83. In addition, relatively recent studies in the fruit fly and zebrafish have confirmed the importance of immunological signaling pathways in the muscle in both the humoral81 and the cellular80 immune responses against pathogens. Further studies are required to understand the significance of muscle expressed genes also in the host response against mycobacterial infections.

Lee et al.,21 described a new carbohydrate-binding lectin family, the Intelectins, with concomitantly proposed function in the innate immunity through microbial recognition23,34,83. Two ITLN genes (ITLN1 and ITLN2) have been identified in humans, whereas the exact number of protein coding itln genes in zebrafish is elusive varying between six (The Zebrafish Information Network, ZFIN) and nine annotated members (Ensembl genome browser). However, not all are expressed in significant amounts. Our genome-wide gene expression analysis showed the highest expression levels for itln1, itln2, itln2-like and itln3 in the PBS injected fish with an average log2 expression of 9.6, 11.9, 13.0 and 10.5, respectively (the lowest average log2 expression was 6.9 for a probe A_15_P113269; ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1, ankk1). This was consistent with Lin et al., who reported the highest expression levels for itln1, itln2 and itln325. Since their discovery, a large number of studies have reported the induction of the expression of ITLN genes in different species in bacterial25,30,31,32, parasite84,85,86 and viral87 infections. In addition, although the publicly available transcriptomic data of M. marinum infected zebrafish embryos by Benard et al., (Gene Expression Omnibus identifier: GSE76499) shows differential regulation of itln transcripts in this model58, to our knowledge itln up-regulation in a mycobacterial infection has not previously been extensively reported in the literature. In our microarray analysis of M. marinum infected adult zebrafish, three of the differentially expressed genes were members of the intelectin family (itln2, itln2-like and itln3). The observed decrease in itln2 expression as well as the induction of itln3 in these fish was also later confirmed by a qPCR-based quantification of samples from a separate mycobacterial infection experiment. In line with this, a qPCR analysis of M. marinum infected zebrafish embryos revealed a significant induction of itln3 expression post mycobacterial infection, a result which corresponds well with the data by Benard et al., (GSE76499)58. In embryos, we also observed up-regulation of itln1, itln2 as well as an itln2-like in response to a mycobacterial infection. While itln1 had identical induction kinetics to itln3 with significant up-regulation starting at 2 dpi, the itln2-like and itln2 genes were induced later in the infection at 4 and 7 dpi, respectively. Of note, the expression of itln2 at 1 dpi (Fig. 1G) was below the limit of detection in the qPCR. Furthermore, up-regulation of itln3 was observed after an S. pneumoniae infection in zebrafish embryos, suggesting that this gene can be induced also in an immune response against pneumococcus. All in all, in this study we demonstrated the inducibility of intelectin genes in both a mycobacterial and a S. pneumoniae infection as well as the down-regulation of itln2 and itln2-like transcripts after mycobacterial inoculation in adult zebrafish.

Transcriptomic analyzes have identified several so called classical liver-expressed acute phase protein (APP) genes such as c-reactive protein (crp) and serum amyloid a (saa) also in fish species88,89,90. In addition, bacterial infections in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)91, channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus)31 as well as in zebrafish25 have resulted in liver-specific induction of certain itln gene members. Our mRNA expression analysis of unchallenged zebrafish confirmed the previously published tissue-restricted expression pattern of zebrafish itln genes25. While itln2 is expressed almost exclusively in the intestine, the highest relative expression compared to the housekeeping gene was in the liver for itln3. In the current study, we produced Strep-tagged® zebrafish Itln3 in a mammalian expression system to study whether Itln3 could act as a potential APP in microbial recognition. Similarly to human ITLN134,83,92, zebrafish Itln3 was secreted into the culture media. However, although Tsuji et al., (2009) has reported the ability of human ITLN1 to bind to galactofuranosyl (Galf) residues on the mycobacterial cell membrane83, recombinant Itln3 did not bind readily to M. marinum in vitro. Similarly, Itln3 did not bind to E. coli or S. pneumoniae in our hands.

To our knowledge, only two in vivo studies on the significance of Intelectins in the host response against pathogens have been conducted35,36. While the lack of ITLN2 was associated with an increased susceptibility toward the parasite T. spiralis in C57BL/10 mice36, the over-expression of ITLN1 and ITLN2 in the lungs of transgenic mice could not restrict either a Nippostrongylus brasiliensis or a Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection differently from the littermate controls35. While genes of the innate immune system can be studied autonomously in zebrafish embryos, which lack a functional adaptive immunity50, adult zebrafish have a highly similar immune system compared to humans93. Correspondingly, the embryonic M. marinum infection model has revealed important insights into the mechanisms of the innate immunity in mycobacterial host resistance (reviewed in50,51) and the adult model has proven its usefulness e.g. in modelling a latent infection56 and disease reactivation56,60. In order to obtain a more comprehensive view about the in vivo significance of ITLNs in a mycobacterial infection, we used the itln3 deficient zebrafish together with both the embryonic as well as the adult M. marinum models. In these experiments, the comparison of survival and mycobacterial burden between itln3 mutant fish and their WT siblings did not reveal any differences in either of the mutant lines (itln3uta145 and itln3uta148). Also, it was demonstrated that this was independent of the site or timing of the microinjection in the embryos (yolk sac at 0 dpf vs. blood circulation valley at 2 dpf). Collectively, we conclude that zebrafish itln3 is not required for the resistance against a mycobacterial infection.

Genetic compensation is a well-known phenomenon in model organisms with experimental gene knockouts70. In this process, the specific function of a knockout gene can be restored by additional naturally occurring mutations or transcriptional changes in other genes70. Here, we report the up-regulation of itln3 as well as another member of the intelectin family, itln1, in a M. marinum infection of zebrafish embryos with analogous induction kinetics. To overcome potential compensatory effects of itln1 in our itln3 mutants, we knocked down itln1 by morpholinos and performed simultaneous M. marinum infections in the itln3 mutant embryos. Silencing itln1 in itln3 mutants during a M. marinum infection did not reveal any differences compared to controls, demonstrating that itln1 expression does not compensate for the lack of a functional itln3 in a M. marinum infection. Moreover, our qPCR quantification of itln1, itln2 and itln2-like in the uninjected and M. marinum infected zebrafish embryos as well as adult zebrafish did not reveal transcriptional compensation for itln3 in the homozygous mutant background. Similarly, the depletion of lymphocytes in the adult zebrafish did not reveal the importance for Itln3 in the immunity against a M. marinum infection. All in all, our data indicate that despite being strongly induced by a mycobacterial infection, itln3 is dispensable for the immune response against M. marinum both in embryonic and adult zebrafish.

Methods

Zebrafish lines and maintenance

The zebrafish maintenance and all of the experiments were in accordance with the Finnish Act on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes (497/2013) as well as the EU Directive on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes (2010/63/EU). Experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Board of Finland (permit for zebrafish maintenance: ESAVI/10079/04.10.06/2015; permits for the experiments: ESAVI/2464/04.10.07/2017, ESAVI/10823/04.10.07/2016, ESAVI/2235/04.10.07/2015 and ESAVI/11133/04.10.07/2017). WT AB fish as well as in-house CRISPR/Cas9 produced F2-generation itln3uta145 and F2- or F3-generation itln3uta148 mutant zebrafish were used in the embryonic experiments, whereas three- to seven-month-old AB, il10e46, itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 zebrafish were used in the experiments with the adult fish. Zebrafish embryos were maintained according to standard protocols in embryonic medium E3 (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2, 0.33 mM MgSO4, 0.0003 g/l methylene blue) at 28.5 °C until 7 dpf. Maintenance of the adult zebrafish was as follows; unchallenged fish were kept in a conventional flow through system (Aquatic Habitats, Florida, USA) with an automated light/dark cycle of 14 h/10 h and fed once a day with Gemma Micro 500 (Skretting, Stavanger, Norway) or twice with SDS 400 (Special Diets Services, Essex, UK) feed. M. marinum infected adults were kept in a separate flow through system (Aqua Schwarz GMbH, Göttingen, Germany) with the above-mentioned light/dark cycle and fed once a day with Gemma Micro 500 (Skretting) or SDS 400 (Special Diets Services). Infected fish were monitored daily. Humane endpoint criteria pre-defined in the animal experiment permits were applied throughout the follow-up.

Experimental M. marinum infections

M. marinum (ATCC 927 -strain) culture and the adult zebrafish inoculations were performed as described previously56. In the M. marinum infections of the zebrafish embryos, a total volume of 1–2 nl was microinjected either into the yolk sac (0 dpf) or into the blood circulation valley (2 dpf) by using a borosilicate capillary needle (Sutter instrument Co., California, USA), a micromanipulator (Narishige International, London UK) and a PV830 Pneumatic PicoPump (World Precision Instruments, Florida, USA). 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone-40 (PVP) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.3 mg/ml phenol red (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a mycobacterial carrier solution. Prior to circulation valley injections, the 2 dpf zebrafish were anesthetized with 0.02% 3-amino benzoic acid ethyl ester (Sigma-Aldrich). Embryonic infections were visualized with a Stemi 2000 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) and the survival of the embryos followed daily. Adult zebrafish were first anesthetized with 0.02% 3-amino benzoic acid ethyl ester (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA), and then injected with 5 µl of M. marinum in a suspension of 10 mM PBS and 0.3 mg/ml phenol red (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) into the abdominal cavity using a 30 gauge Omnican 100 insulin needle (Braun, Melsungen, Germany). The M. marinum amounts from both the embryonic and adult infections were verified by plating bacterial inoculates on 7H10 agar (Becton Dickinson, New Jersey, USA) plates and counting the colony forming units (CFU) 5-days after plating.

Gene expression microarray

RNA was extracted from the zebrafish organ blocks (includes all the organs of the abdominal cavity) with TRIreagent (Molecular Research Center, Ohio, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Microarray procedures were carried out by the Turku Centre for Biotechnology at the Finnish Microarray and Sequencing Centre by using a Zebrafish (V3) Gene Expression Microarray, 4 × 44 K (Agilent Technologies, California, USA). In short, 100 ng of total RNA was amplified and Cy3-labeled with Low Input Quick Amp Labeling kit, one-color (Agilent), processed using the RNA Spike-In Kit, one-color (Agilent) and quality controlled with 2100 bioanalyzer RNA 6000 Nano kit (Agilent). Labelling and hybridization of the transcripts were done onto Agilent’s 4 × 44 K Zebrafish v3 array (Design ID 026437) using GE Hybridization Kit (Agilent). Microarrays were scanned with an Agilent scanner G2565CA using a profile AgilentHD_GX_1Color. Numerical results were obtained with Feature Extraction Software v. 10.7.3 (Agilent) with the protocol GE1_107_Sep09 and the signal intensities normalized prior further analysis. Cut-off value (log2 fold change >\(|3|\)) for the up- and down-regulated genes was chosen in order to obtain approximately 100 differentially expressed candidate genes for further evaluation. Gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed using GOrilla61,62 with two unranked lists of genes (Target list: log2 fold change >\(|3|\), Background list: log2 fold change <\(|3|\)) using Danio rerio genome assembly.

qPCR

For gene expression analysis of the zebrafish embryo samples, genomic DNA (gDNA) removal and RNA isolation were performed using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Adult zebrafish RNA was extracted from the organ blocks, liver, spleen, kidney and intestine with TRIreagent (Molecular Research Center) following the associated protocol. The genomic DNA (gDNA) from the RNA samples of the adult fish was removed with RapidOut DNA Removal Kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, USA). RNA quality was controlled with either 1.5% agarose Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) gel electrophoresis or by using Fragment Analyzer system (Advanced Analytical, Inc., Ankeny, USA) and the Standard Sensitivity RNA Analysis Kit (15 nt) (Advanced Analytical). All reverse transcriptions were done by using the SensiFASTTM cDNA synthesis kit (BioLine, London, UK), and the gene expression levels of the target genes were determined from the cDNA with quantitative PCR (qPCR) using the PowerUp™ SYBR® master mix (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and CFX96™ detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, California, USA). CFX Manager software (v. 3.1; Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used for data analysis. Target gene expression was normalized to the eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1, like 1 (eef1a1l1 or ef1a)94 expression using the 2−ΔCt method. M. marinum burden from the zebrafish was determined from the total DNA by qPCR with MMITS-specific primers56. Embryo DNA for mycobacterial quantification was isolated with standard ethanol precipitation procedure utilizing the following lysis buffer: 10 mM Tris (pH 8.2), 10 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 200 µg/ml Proteinase K (Thermo Fischer Scientific), whereas TRIreagent (Molecular Research Center) was used for the adult fish DNA isolations. No reverse transcriptase control samples were added to the gene expression analyses, and no template control (H2O) samples were included in all of the qPCR experiments to preclude contamination. Specificity and the correct size of the qPCR products were verified by melt curve analysis and 1.5% agarose TAE gel electrophoresis. Undetectable qPCR products with incorrect melt curves were given a Ct-value of 40 for the gene expression analyses, and the expression was considered to be below detection. qPCR primers used in the study are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis

We have previously set-up our in-house zebrafish CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis method based on the protocol published by Hruscha and Schmid (2015)65,95. First, guide RNA (gRNA) target sequences for itln3 were designed with the CRISPR design tool (http://crispr.mit.edu/), and validated with the Casellas laboratory sgRNA tool96 and the standard nucleotide BLAST analysis97. itln3 exon 2 gRNA was produced by in vitro transcription using the MEGAshortscript T7 Transcription Kit (Ambion Life Technologies, CA, USA). 2000 pg of gRNA, 330 pg of cas9 mRNA (Sigma-Aldrich and Invitrogen, California, USA) and 1.5 ng of phenol red (Sigma-Aldrich) tracer were injected into one-cell-stage AB zebrafish embryos, and the success of mutagenesis was evaluated with the T7 endonuclease I (T7EI)- and the heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA) from isolated DNA of 2 dpf embryos49. Gel images were obtained with ChemiDoc™ XRS+ system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and analyzed with Image Lab software (v. 5.2; Bio-Rad Laboratories). To establish the itln3 knockout fish line, gRNA was microinjected into zebrafish embryos and the F0-generation fish grown to adulthood. Individual outcrosses of the F0-zebrafish with the Tupfel long fin (TL) fish allowed us to screen for germline transmitted mutations and to identify nonsense mutations of interest in the F1-progeny. The F1-progeny screen was done from the tailfin DNA of the adult zebrafish with HMA followed by Sanger sequencing in our institutes core-facility (MED, University of Tampere). The F1-zebrafish carrying individual mutations of interest were spawn together to obtain F2-generation progeny for the experiments. In the end, a total of two different itln3 mutation (itln3uta145 and itln3uta148) bearing zebrafish lines were used in the study.

PCR based genotyping

F2-generation itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 zebrafish lines were mainly genotyped using PCR. To this end, template DNA was either isolated using a standard ethanol precipitation protocol, or with a rapid tissue lysis protocol98. Primers were designed for both the WT and the mutated sequences at the gRNA target region; WT itln3uta145 F: 5′-ATGCTAGGTTGAGGAGCATC-3′, mutant itln3uta145 F: 5′-ATGCTAGGTTGAGGAGCTCG-3′, WT itln3uta148 F: 5′-CTAGGTTGAGGAGCATCGCT-3′, mutant itln3uta148 R: 5′-CCGAGCTGATACTTACCTAGC-3′, and amplified with the appropriate flanking primer: F: 5′-GGAGCTGTCACTCCAAAGCC-3′ or R: 5′-GTGGTTGATCAACCATTCAGCAC-3′. To determine the genotypes of the itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 zebrafish, individual PCR reactions with both WT and mutant primer pairs were prepared for each fish and 1.5% agarose TAE gel electrophoresis was performed to analyze the PCR products.

Morpholino injections

Splice-blocking morpholino (SB) for itln1 (5′-CTAATTCTGTACTTACTCGATTCAC-3′) was designed by and ordered from GeneTools, LLC (Philomath, Oregon, USA). The targeted genomic sequence was verified from our AB and itln3 knockout zebrafish lines by sequencing99. In order to ensure no adverse effects on survival or the phenotype of the morpholino injected embryos in later experiments, the oligonucleotide dosage was first titrated by using three different quantities (7.1 ng, 2.8 ng and 1.1 ng), and the survival of the embryos was observed daily until 7 dpf. The embryos were imaged using Zeiss Lumar V12 fluorescence microscope. The selected microinjection volume was set to 2 nl containing 2.8 ng of SB or random control (RC) morpholino as well as 7 mg/ml of tetramethylrhodamine dextran (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 0.3 mg/ml phenol red tracer suspended in PBS. In the morpholino-M. marinum co-injections, the previously described suspension with 2% PVP was used as a mycobacterial carrier solution. All of the morpholino injections as well as morpholino and M. marinum co-injections were done before the 16-cell-stage of development into the yolk sac of the embryos. Similarly than in the other M. marinum infection experiments, the mycobacterial counts in the injections were verified by plating. Primers used for the morpholino target site sequencing were F: 5′-TGCACAGGTATTCACCATTTTATGATG-3′ and R: 5′-AAGTTCTCTGCAGCTTCTTGC-3′ and for the verification of the morpholino functionality as well as quantification of the WT itln1 expression by qPCR: F: 5′-ATGATGCAGTCAGCTGGTTTTCTTCTG-3′ and R: 5′-GCAGTGACCGACTCTGGAAATTCTCC-3′.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry for the adult zebrafish kidney cells was performed as described previously71. Briefly, itln3uta145 and itln3uta148 fish were euthanized with 0.04% 3-amino benzoic acid ethyl ester and their kidneys isolated and suspended in PBS supplemented with 0.5% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich). Prior analysis, the kidney cells were filtered through a cell strainer cap with a 35 µm mesh (Corning/Thermo Fisher Scientific). Relative amounts of lymphocytes, myeloid cells and blood cell precursors were determined with a FACSCanto II instrument (Becton, Dickinson, New Jersey, USA) and the data was analyzed with the FlowJo program (v. 7.5; Tree Star, Inc, Oregon, USA). Gating of the blood cell populations is based on previous publications60,71,100,101.

Dexamethasone mediated immunosuppression

Similarly as described previously60, 25 mg of dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich) was mixed with gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich) and used to coat 10 g of SDS400 food (Special Diets Services). During the experiment, a daily dose of 10 µg of dexamethasone (4 mg of food) was given per fish for a total of 5 weeks. A new batch of dexamethasone food was prepared for usage every second week. Dexamethasone was administered for a total of five weeks and the well-being of the fish monitored daily.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculations have been described in our previous publication100. Statistical analyses were done with the Prism v. 5.02 (GraphPad Software, California, USA). In the survival experiments a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used, whereas in the flow cytometry and qPCR analyses a nonparametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney analysis was performed. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Data Availability

Gene expression microarray data has been submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository and can be found with the identifier code: GSE120552. Other generated and analyzed data is available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (2017).

Lerner, T. R., Borel, S. & Gutierrez, M. G. The innate immune response in human tuberculosis. Cellular Microbiology 17, 1277–1285 (2015).

Möller, M., de Wit, E. & Hoal, E. G. Past, present and future directions in human genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58, 3–26 (2010).

Meyer, C. G. & Thye, T. Host genetic studies in adult pulmonary tuberculosis. Semin. Immunol. 26, 445–453 (2014).

Shimokata, K., Kawachi, H., Kishimoto, H., Maeda, F. & Ito, Y. Local cellular immunity in tuberculous pleurisy. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 126, 822–824 (1982).

Onwubalili, J. K., Scott, G. M. & Robinson, J. A. Deficient immune interferon production in tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 59, 405–413 (1985).

Denis, M. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) augments cytolytic activity of natural killer cells toward Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected human monocytes. Cell. Immunol. 156, 529–536 (1994).

Zhang, M. et al. Interleukin 12 at the site of disease in tuberculosis. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 1733–1739 (1994).

Alcaïs, A., Fieschi, C., Abel, L. & Casanova, J. Tuberculosis in children and adults: two distinct genetic diseases. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1617–1621 (2005).

Flynn, J. L. et al. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 178, 2249–2254 (1993).

Cooper, A. M. et al. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J. Exp. Med. 178, 2243–2247 (1993).

Flynn, J. L. et al. IL-12 increases resistance of BALB/c mice to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 155, 2515–2524 (1995).

Cooper, A. M., Magram, J., Ferrante, J. & Orme, I. M. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 186, 39–45 (1997).

Dittrich, N. et al. Toll-like receptor 1 variations influence susceptibility and immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 95, 328–335 (2015).

Stappers, M. H. T. et al. TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 gene polymorphisms are associated with increased susceptibility to complicated skin and skin structure infections. J. Infect. Dis. 210, 311–318 (2014).

Qi, H. et al. Toll-like receptor 1(TLR1) Gene SNP rs5743618 is associated with increased risk for tuberculosis in Han Chinese children. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 95, 197–203 (2015).

Tanne, A. et al. A murine DC-SIGN homologue contributes to early host defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2205–2220 (2009).

Guo, Y., Liu, Y., Ban, W., Sun, Q. & Shi, G. Association of mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphisms with the development of pulmonary tuberculosis in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 17, 210 (2017).

Wesener, D. A., Dugan, A. & Kiessling, L. L. Recognition of microbial glycans by soluble human lectins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 44, 168–178 (2017).

Sharon, N. & Lis, H. History of lectins: from hemagglutinins to biological recognition molecules. Glycobiology 14, 53R–62R (2004).

Lee, J. K. et al. Cloning and expression of a Xenopus laevis oocyte lectin and characterization of its mRNA levels during early development. Glycobiology 7, 367–372 (1997).

Yan, J. et al. Comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses of the intelectin gene family: implications for their origin and evolution. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 41, 189–199 (2013).

Komiya, T., Tanigawa, Y. & Hirohashi, S. Cloning of the novel gene intelectin, which is expressed in intestinal paneth cells in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251, 759–762 (1998).

Tsuji, S. et al. Human intelectin is a novel soluble lectin that recognizes galactofuranose in carbohydrate chains of bacterial cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 23456–23463 (2001).

Lin, B. et al. Characterization and comparative analyses of zebrafish intelectins: highly conserved sequences, diversified structures and functions. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 26, 396–405 (2009).

Suzuki, Y. A., Shin, K. & Lönnerdal, B. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a human intestinal lactoferrin receptor. Biochemistry 40, 15771–15779 (2001).

Watanabe, T., Watanabe-Kominato, K., Takahashi, Y., Kojima, M. & Watanabe, R. Adipose Tissue-Derived Omentin-1 Function and Regulation. Compr Physiol 7, 765–781 (2017).

Li, D. et al. Intelectin 1 suppresses the growth, invasion and metastasis of neuroblastoma cells through up-regulation of N-myc downstream regulated gene 2. Mol. Cancer 14, 47 (2015).

Li, D. et al. Intelectin 1 suppresses tumor progression and is associated with improved survival in gastric cancer. Oncotarget 6, 16168–16182 (2015).

Ding, Z. et al. Characterization and expression analysis of an intelectin gene from Megalobrama amblycephala with excellent bacterial binding and agglutination activity. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 61, 100–110 (2017).

Peatman, E. et al. Expression analysis of the acute phase response in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) after infection with a Gram-negative bacterium. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 31, 1183–1196 (2007).

Takano, T. et al. The two channel catfish intelectin genes exhibit highly differential patterns of tissue expression and regulation after infection with Edwardsiella ictaluri. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 32, 693–705 (2008).

Tsuji, S. et al. Capture of heat-killed Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin by intelectin-1 deposited on cell surfaces. Glycobiology 19, 518–526 (2009).

Wesener, D. A. et al. Recognition of microbial glycans by human intelectin-1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 603–610 (2015).

Voehringer, D. et al. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis: identification of intelectin-1 and -2 as Stat6-dependent genes expressed in lung and intestine during infection. Exp. Parasitol. 116, 458–466 (2007).

Pemberton, A. D. et al. Innate BALB/c enteric epithelial responses to Trichinella spiralis: inducible expression of a novel goblet cell lectin, intelectin-2, and its natural deletion in C57BL/10 mice. J. Immunol. 173, 1894–1901 (2004).

Rao, S. et al. Omentin-1 prevents inflammation-induced osteoporosis by downregulating the pro-inflammatory cytokines. Bone Research 6, 1–12 (2018).

Howe, K. et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 496, 498–503 (2013).

Willett, C. E., Zapata, A. G., Hopkins, N. & Steiner, L. A. Expression of zebrafish rag genes during early development identifies the thymus. Dev. Biol. 182, 331–341 (1997).

Willett, C. E., Kawasaki, H., Amemiya, C. T., Lin, S. & Steiner, L. A. Ikaros expression as a marker for lymphoid progenitors during zebrafish development. Dev. Dyn. 222, 694–698 (2001).

Danilova, N. & Steiner, L. A. B cells develop in the zebrafish pancreas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13711–13716 (2002).

Bennett, C. M. et al. Myelopoiesis in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Blood 98, 643–651 (2001).

Lin, A. F. et al. The DC-SIGN of zebrafish: insights into the existence of a CD209 homologue in a lower vertebrate and its involvement in adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 183, 7398–7410 (2009).

Seeger, A., Mayer, W. E. & Klein, J. A complement factor B-like cDNA clone from the zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio). Mol. Immunol. 33, 511–520 (1996).

Lam, S. H., Chua, H. L., Gong, Z., Lam, T. J. & Sin, Y. M. Development and maturation of the immune system in zebrafish, Danio rerio: a gene expression profiling, in situ hybridization and immunological study. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 28, 9–28 (2004).

Danilova, N., Bussmann, J., Jekosch, K. & Steiner, L. A. The immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus in zebrafish: identification and expression of a previously unknown isotype, immunoglobulin Z. Nat. Immunol. 6, 295–302 (2005).

Hwang, W. Y. et al. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 227–229 (2013).

Chang, N. et al. Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in zebrafish embryos. Cell Res. 23, 465–472 (2013).

Uusi-Mäkelä, M. I. E. et al. Chromatin accessibility is associated with CRISPR-Cas9 efficiency in the zebrafish (Danio rerio). PLoS ONE 13, e0196238 (2018).

Meijer, A. H. Protection and pathology in TB: learning from the zebrafish model. Semin Immunopathol 38, 261–273 (2016).

Myllymäki, H., Bäuerlein, C. A. & Rämet, M. The Zebrafish Breathes New Life into the Study of Tuberculosis. Front Immunol 7, 196 (2016).

van Leeuwen, L. M., van der Sar, Astrid, M. & Bitter, W. Animal models of tuberculosis: zebrafish. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 5, a018580 (2015).

Myllymäki, H., Niskanen, M., Oksanen, K. E. & Rämet, M. Animal models in tuberculosis research - where is the beef? Expert Opin Drug Discov 10, 871–883 (2015).

Davis, J. M. et al. Real-Time Visualization of Mycobacterium-Macrophage Interactions Leading to Initiation of Granuloma Formation in Zebrafish Embryos. Immunity 17, 693–702 (2002).

Swaim, L. E. et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection of adult zebrafish causes caseating granulomatous tuberculosis and is moderated by adaptive immunity. Infect. Immun. 74, 6108–6117 (2006).

Parikka, M. et al. Mycobacterium marinum causes a latent infection that can be reactivated by gamma irradiation in adult zebrafish. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002944 (2012).

Meijer, A. H. & Spaink, H. P. Host-pathogen interactions made transparent with the zebrafish model. Curr Drug Targets 12, 1000–1017 (2011).

Benard, E. L., Rougeot, J., Racz, P. I., Spaink, H. P. & Meijer, A. H. Transcriptomic Approaches in the Zebrafish Model for Tuberculosis-Insights Into Host- and Pathogen-specific Determinants of the Innate Immune Response. Adv. Genet. 95, 217–251 (2016).

van der Sar et al. Specificity of the zebrafish host transcriptome response to acute and chronic mycobacterial infection and the role of innate and adaptive immune components. Mol. Immunol 46, 2317–2332 (2009).

Myllymäki, H., Niskanen, M., Luukinen, H., Parikka, M. & Rämet, M. Identification of protective postexposure mycobacterial vaccine antigens using an immunosuppression-based reactivation model in the zebrafish. Dis Model Mech 11, (2018).

Eden, E., Lipson, D., Yogev, S. & Yakhini, Z. Discovering motifs in ranked lists of DNA sequences. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, e39 (2007).

Eden, E., Navon, R., Steinfeld, I., Lipson, D. & Yakhini, Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 48 (2009).

Jinek, M. et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012).

Ran, F. A. et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8, 2281–2308 (2013).

Aspatwar, A. et al. Inactivation of ca10a and ca10b Genes Leads to Abnormal Embryonic Development and Alters Movement Pattern in Zebrafish. PLoS ONE 10, e0134263 (2015).

Hruscha, A. et al. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing with low off-target effects in zebrafish. Development 140, 4982–4987 (2013).

Artimo, P. et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 597 (2012).

Nickless, A., Bailis, J. M. & You, Z. Control of gene expression through the nonsense-mediated RNA decay pathway. Cell Biosci 7, 26 (2017).

Rounioja, S. et al. Defense of zebrafish embryos against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection is dependent on the phagocytic activity of leukocytes. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 36, 342–348 (2012).

Tautz, D. Problems and paradigms: Redundancies, development and the flow of information. BioEssays 14, 263–266 (1992).

Ojanen, M. J. T. et al. The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin furinA regulates zebrafish host response against Mycobacterium marinum. Infect. Immun. 83, 1431–1442 (2015).

Meijer, A. H. et al. Transcriptome profiling of adult zebrafish at the late stage of chronic tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium marinum infection. Mol. Immunol. 42, 1185–1203 (2005).

van der Vaart, M., Spaink, H. P. & Meijer, A. H. Pathogen recognition and activation of the innate immune response in zebrafish. Adv Hematol 2012, 159807 (2012).

Hegedus, Z. et al. Deep sequencing of the zebrafish transcriptome response to mycobacterium infection. Mol. Immunol. 46, 2918–2930 (2009).

Rougeot, J. et al. RNA sequencing of FACS-sorted immune cell populations from zebrafish infection models to identify cell specific responses to intracellular pathogens. Methods Mol. Biol. 1197, 261–274 (2014).

Benard, E. L., Rougeot, J., Racz, P. I., Spaink, H. P. & Meijer, A. H. Transcriptomic Approaches in the Zebrafish Model for Tuberculosis-Insights Into Host- and Pathogen-specific Determinants of the Innate Immune Response. Adv. Genet. 95, 217–251 (2016).

Kenyon, A. et al. Active nuclear transcriptome analysis reveals inflammasome-dependent mechanism for early neutrophil response to Mycobacterium marinum. Sci Rep 7, 6505 (2017).

Apidianakis, Y. et al. Profiling early infection responses: Pseudomonas aeruginosa eludes host defenses by suppressing antimicrobial peptide gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2573–2578 (2005).

Apidianakis, Y. et al. Involvement of skeletal muscle gene regulatory network in susceptibility to wound infection following trauma. PLoS ONE 2, e1356 (2007).

Yang, H., Kronhamn, J., Ekström, J., Korkut, G. G. & Hultmark, D. JAK/STAT signaling in Drosophila muscles controls the cellular immune response against parasitoid infection. EMBO Rep. 16, 1664–1672 (2015).

Chatterjee, A., Roy, D., Patnaik, E. & Nongthomba, U. Muscles provide protection during microbial infection by activating innate immune response pathways in Drosophila and zebrafish. Dis Model Mech 9, 697–705 (2016).

Lin, S., Fan, T., Wu, J., Hui, C. & Chen, J. Immune response and inhibition of bacterial growth by electrotransfer of plasmid DNA containing the antimicrobial peptide, epinecidin-1, into zebrafish muscle. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 26, 451–458 (2009).

Frost, R. A., Nystrom, G. J. & Lang, C. H. Lipopolysaccharide regulates proinflammatory cytokine expression in mouse myoblasts and skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 283, 698 (2002).

French, A. T. et al. Up-regulation of intelectin in sheep after infection with Teladorsagia circumcincta. Int. J. Parasitol. 38, 467–475 (2008).

Pemberton, A. D., Knight, P. A., Wright, S. H. & Miller, H. R. P. Proteomic analysis of mouse jejunal epithelium and its response to infection with the intestinal nematode, Trichinella spiralis. Proteomics 4, 1101–1108 (2004).

Datta, R. et al. Identification of novel genes in intestinal tissue that are regulated after infection with an intestinal nematode parasite. Infect. Immun. 73, 4025–4033 (2005).

Podok, P., Xu, L., Xu, D. & Lu, L. Different expression profiles of Interleukin 11 (IL-11), Intelectin (ITLN) and Purine nucleoside phosphorylase 5a (PNP 5a) in crucian carp (Carassius auratus gibelio) in response to Cyprinid herpesvirus 2 and Aeromonas hydrophila. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 38, 65–73 (2014).

Winkelhake, J. L., Vodicnik, M. J. & Taylor, J. L. Induction in rainbow trout of an acute phase (C-reactive) protein by chemicals of environmental concern. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C, Comp. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 74, 55–58 (1983).

Kovacevic, N., Hagen, M. O., Xie, J. & Belosevic, M. The analysis of the acute phase response during the course of Trypanosoma carassii infection in the goldfish (Carassius auratus L.). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 53, 112–122 (2015).

Talbot, A. T., Pottinger, T. G., Smith, T. J. & Cairns, M. T. Acute phase gene expression in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) after exposure to a confinement stressor: A comparison of pooled and individual data. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 27, 309–317 (2009).

Gerwick, L., Corley-Smith, G. & Bayne, C. J. Gene transcript changes in individual rainbow trout livers following an inflammatory stimulus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 22, 157–171 (2007).

Kerr, S. C. et al. Intelectin-1 is a prominent protein constituent of pathologic mucus associated with eosinophilic airway inflammation in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 189, 1005–1007 (2014).

Renshaw, S. A. & Trede, N. S. A model 450 million years in the making: zebrafish and vertebrate immunity. Dis. Model. Mech. 5, 38–47 (2012).

Tang, R., Dodd, A., Lai, D., McNabb, W. C. & Love, D. R. Validation of zebrafish (Danio rerio) reference genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR normalization. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 39, 384–390 (2007).

Hruscha, A. & Schmid, B. Generation of zebrafish models by CRISPR /Cas9 genome editing. Methods Mol. Biol. 1254, 341–350 (2015).

Krebs, J. CRISPR design tool and protocol (2015). Data retrieved: 07:16, May 19, GMT. https://figshare.com/articles/CRISPR_Design_Tool/1117899 (2015).

Altschul, S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic acids research 25, 3389–3402 (1997).

Meeker, N. D., Hutchinson, S. A., Ho, L. & Trede, N. S. Method for isolation of PCR-ready genomic DNA from zebrafish tissues. BioTechniques 43, 614 (2007).

Turpeinen, H. et al. Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 7 (PCSK7) Is Essential for the Zebrafish Development and Bioavailability of Transforming Growth Factor beta1a (TGFbeta1a). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36610–36623 (2013).

Harjula, S. E., Ojanen, M. J. T., Taavitsainen, S., Nykter, M. & Rämet, M. Interleukin 10 mutant zebrafish have an enhanced interferon gamma response and improved survival against a Mycobacterium marinum infection. Sci Rep 8, 10360 (2018).

Traver, D. et al. Transplantation and in vivo imaging of multilineage engraftment in zebrafish bloodless mutants. Nat. Immunol. 4, 1238–1246 (2003).

Acknowledgements