Abstract

Synchronization of behavior such as gestures or postures is assumed to serve crucial functions in social interaction but has been poorly studied to date in schizophrenia. Using a virtual collaborative environment (VCS), we tested 1) whether synchronization of behavior, i.e., the spontaneous initiation of gestures that are congruent with those of an interaction partner, was impaired in individuals with schizophrenia compared with healthy participants; 2) whether mimicry of the patients’ body movements by the virtual interaction partner was associated with increased behavioral synchronization and rapport. 19 patients and 19 matched controls interacted with a virtual agent who either mimicked their head and torso movements with a delay varying randomly between 0.5 s and 4 s or did not mimic, and rated feelings of rapport toward the virtual agent after each condition. Both groups exhibited a higher and similar synchronization behavior of the virtual agent forearm movements when they were in the Mimicry condition rather than in the No-mimicry condition. In addition, both groups felt more comfortable with a mimicking virtual agent rather than a virtual agent not mimicking them suggesting that mimicry is able to increase rapport in individuals with schizophrenia. Our results suggest that schizophrenia cannot be considered anymore as a disorder of imitation, particularly as regards behavioral synchronization processes in social interaction contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is now well admitted that individuals have a tendency to synchronize their behaviors, which constitutes a key form of social exchange throughout the lifetime. Prototypical examples are found in everyday life when people are walking side by side and synchronize unconsciously their steps as well as their attitudes while talking to each other1. A substantial number of studies have shown that the foundation for this laid very early in development, as newborn infants spontaneously imitate a range of simple behaviors of an adult model2.

In addition to mimicry, which is typically defined as the spontaneous, immediate (at the split of a second) imitation of gestures, postures, mannerisms and the dynamics of movement of another person3,4,5, behavioral synchronization denotes the mutual alignment of interaction partners’ behavior on a larger time-scale. Both processes have been found to be critical in human-human interactions since they are suggested to be tied to liking, rapport and empathy6. For example, there is a large amount of evidence that being mimicked promotes rapport7, trust8, altruistic behavior and liking between interacting partners9 and, in turn increases behavioral synchronization and movements in the mimicked partner via a variety of psychological and neural mechanisms10.

In comparison to other types of deliberate, goal-directed, voluntary imitation such as social learning11 or imitation learning12, one crucial aspect of behavioral synchronization is the fact that it occurs without awareness. Indeed, behavioral synchronization is nonconscious, unintentional, effortless, and has the potency to increase prosocial behavior mostly when interacting people are not aware that their behavior is being mimicked. By contrast, overt detection of being mimicked can have deleterious effects on affiliation13 or liking14. In addition, as mimicry of other people’s behavior during social interaction is unconscious, it is thus fundamentally considered as a social behavior modulated by social cues such as eye gaze or social status15.

In the field of psychopathology and neurodevelopmental disorders, mimicry has been particularly studied in autism spectrum disorders. A recent meta-analysis16 indicated that individuals with autism exhibit significant impairments in behavioral synchronization skills on a variety of tasks including body movements, vocalizations, or facial expressions. The same results were found regarding mimicry17,18. Contrary to autism, behavioral synchronization and particularly its relationships with interpersonal functioning has been poorly studied in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. As a whole, prior studies have repeatedly shown impaired voluntary imitation of face and complex hand gesture movements in schizophrenia patients in comparison to healthy partners19,20,21, especially when the production of a voluntary imitation depends upon working memory22,23. The few studies that focused on behavioral synchronization have produced mixed results. Whereas some studies showed impaired behavioral synchronization of emotional stimuli24,25, a recent study by Simonsen et al.26 failed to find any evidence of such impairment when controlling emotional and cognitive confounding variables in their group of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Importantly, previous research in schizophrenia has mainly targeted nonsocial voluntary imitation or synchronization behavior of either complex or simple movements21 and employed experimental laboratory paradigms measuring specific body movements such as hands22, mouth21, or emotions expression25,27,28. In contrast, mimicry is traditionally studied during naturalistic paradigms that measure the frequency of mimicked movements during social interactions between a participant and a confederate (e.g. conversation).

Recent studies have found that automatic imitation10 or mimicry29 are independent of measures of empathy and social cognition. In line with these findings, reflective processes underlying social cognition (requiring effortful controlled processes) including metalizing, emotion regulation and perception of social stimuli (faces and voices), have been found to be systematically impaired in schizophrenia, while more reflexive aspects of social cognition (i.e. more automatic processes), such as motor resonance or emotion contagion, may be intact30. Therefore, we believe that mimicry (which is a reflexive aspect of social cognition) could constitute a promising tool for social rehabilitation in schizophrenia.

Recent advances in collaborative virtual environments (CVEs) have shown the potential of virtual reality for enhancing ecological validity while maintaining experimental control in social neuroscience research31. Indeed, contrary to a real human partner, virtual agents can be programmed to automatically mimic the participant’s movements after an accurate and fully controlled time delay. Importantly, a large amount of research has shown that individuals react towards virtual agents similarly than towards real people32,33. Accordingly, several studies have used CVEs to explore the positive effects of mimicry on interaction, and provided consistent results showing that mimicking virtual agents are perceived as more persuasive34, likable35, and trustworthy36.

For the reasons mentioned above, this study aimed to investigate 1) whether synchronization of behavior, i.e., the spontaneous initiation of gestures that are congruent with those of an interaction partner, was impaired in individuals with schizophrenia compared with healthy participants; 2) whether manipulating mimicry by a virtual agent would impact (a) synchronization behavior; (b) and the feeling of rapport associated with the virtual agent in two groups of nonclinical individuals and schizophrenia patients.

Results

Synchronization behavior

Results revealed a significant effect of mimicry (F(1,36) = 4.69, p = 0.037, η2p = 0.12). This result displayed on Fig. 1 indicates that participants exhibited a higher synchronization behavior of the virtual agent forearm movements when they were in the Mimicry condition (21.4%) rather than in the No-mimicry condition (16.2%). The analysis failed to reveal any group difference (Tables 1 and 2).

Mean percentage of the trials where a forearm imitation motion between virtual agent and participant is detected. Left columns refer to the no-mimicry conditions and right columns refer to the mimicry condition. Indicative information is provided by the colors where white columns refer to the schizophrenia group whereas black columns correspond to the control group. Error bars correspond to the standard deviation around the mean.

Amount of non-verbal behavior

The results of the ANOVA Groups (2) × Mimicry (2) performed on the range of motion of the left forearm revealed a significant Mimicry effect (F(1,36) = 7.02, p = 0.012, η2p = 0.16) indicating that both groups exhibited larger arms movement when facing an mimicking virtual agent rather than an virtual agent not mimicking them (respectively 0.083 vs. 0.058 in arbitrary units). In other words, mimicry increased the amount of nonverbal behavior (i.e. movements) in both groups (Tables 1 and 2).

Rapport

Regarding the questions evaluating how much participants felt comfortable during the interaction, results demonstrated a statistically significant effect of mimicry for one of the three questions (F(1,36) = 6.52, p = 0.015, η2p = 0.15) indicating that both groups felt more comfortable with a mimicking virtual agent rather than a virtual agent not mimicking them (respectively +1.55 vs. +1.08). For the question associated with willingness to interact with the virtual agent in the future, no main effect was found statistically significant (Tables 1 and 2). A significant Group × Mimicry interaction was found significant for likeness (F(1,36) = 4.92, p = 0.033, η2p = 0.12), however the post-hoc decomposition of this interaction failed to reveal any significant difference between the conditions. This is due to the between/within design of this interaction and therefore prevents any interpretation of such result. We also collapsed the four items to obtain a rapport total score, that is, rapport, attractiveness, likeness, and willingness to interact. Rapport total score also failed to found statistical differences (Group effect F(1,36) = 0.14, p = 0.71, η2p = 0.004; Mimicry effect F(1,36) = 3.74, p = 0.06, η2p = 0.094; Group × Mimicry interaction F(1,36) = 0.48, p = 0.49, η2p = 0.013), however, we note here a statistical tendency (p = 0.06) with a small to medium effect size (η2p = 0.094) for the mimicry condition.

Mimicry, rapport and psychotic symptomatology

Regarding psychotic dimensions, range of motion in the Mimicry condition negatively correlated with the positive dimension of the five-factor model of the PANSS (r = −0.57, p = 0.034) and the perceived attractiveness (Q2) in the Mimicry condition positively correlates with the CPZ equivalent dose (r = 0.58, p = 0.029). No other significant correlations were found between Mimicry, rapport, psychotic symptomatology, and other clinical and demographic variables. After applying Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons with an alpha value of 0.05, no significant correlations remained statistically significant (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study investigated synchronization behavior during an interaction with a virtual agent in individuals with schizophrenia.

We programmed a virtual agent to mimic participants’ head and torso movements with a delay varying randomly between 0.5 s to 4 s, compared to a non-mimicry condition. We measured synchronization behavior of forearm movements, responses to being mimicked (i.e. rapport) and amount of non-verbal behaviors, between the two conditions.

First, our findings revealed that schizophrenia patients displayed intact synchronization behavior during interaction with virtual agents compared to the healthy controls group. Indeed, the two groups of participants exhibited similar and a higher synchronization behavior of the virtual agent forearm movements when they were in the mimicry condition rather than in the non-mimicry condition. In addition, both groups exhibited larger arms movement when facing a mimicking virtual agent rather than a virtual agent not mimicking them. On the one hand, this result appears in line with the recent study by Simonsen et al.26 who showed that their schizophrenia group displayed intact automatic imitation compared to matched healthy individuals. On the other hand our study contrasts with the majority of previous findings showing impaired imitation abilities in schizophrenia. First, and as stated by Simonsen et al.26, previous findings assessed voluntary imitation21,22,23 or automatic imitation of emotional stimuli24,25 without controlling for the cognitive, motoric, and/or emotional deficits associated with schizophrenia. Thus it makes difficult to conclude whether imitation deficits were primary or secondary to aforementioned other deficits. Second, our experiment focused on the behavioral synchronization with a virtual agent on a larger time-scale, whereas Simonen et al.26 examined automatic imitation of finger movements presented via short video sequences. Consequently, our findings indicate that the fundamental tendency to synchronize with the behavior of others in social interactions is preserved in individuals with schizophrenia. Additionally, our finding are in line with previous studies in nonclinical individuals34,35 showing that virtual agents have the potential to induce behavioral synchronization and mimicry during interactive paradigms and extends this result to individuals with schizophrenia disorder. Our results also fit well with the results of Riehle & Lincoln37. In their study the authors assessed the amount of smiling and mimicry of smiling via electromyography during a dyadic interaction in participants with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Similarly with our results, they did not find evidence of reduced mimicry of smiling in a face-to-face interaction in the patients group. Their results are particularly relevant with regards to our study. As contrary to our experimental task consisting of an interaction with a virtual agent, they used an ecological task (brief face-to-face conversation) during a human-human interaction. Taken together, these findings suggest that behavioral synchronization during social interaction is preserved in schizophrenia patients”.

Secondly and as hypothesized, our results indicated that behavioral synchronization was associated with better rapport in our two groups. Indeed, both groups felt more comfortable with a virtual agent that mimicked their behavior than the one that did not. In addition and regarding rapport, we found a marginally significant effect in the mimicry condition when we collapsed the four measures of rapport used in our study. This is consistent with previous research using virtual agents and mimicry that showed that mimicking virtual agents are perceived as more likable35 and trustworthy36. In a therapeutic context it may be translated in patients being more willing and feeling more comfortable to share personal information. Previous studies have shown that individuals evaluate therapeutic alliance with a virtual agent in a positive manner and are willing to share their personal information38,39. Associating mimicry and the use of virtual agents controlled by artificial intelligence or algorithm or virtual agents controlled by therapist/clinician may be a promising option to increase access and engagement to psychological services40.

It must be however noted that we did not find specific effects of mimicry on any of our other dependent measures (attractiveness, likeness, willingness to interact) suggesting that these measures of rapport and connectedness could not be adequate in the context of virtual environment. A validated scale of rapport in collaborative virtual environments could be particularly useful for future studies. It is worth mentioning that ratings of liking, and self-other overlap also show inconsistent effects of mimicry in both virtual environment and traditional research settings, leading some researchers to suggest that the positive social effect of being mimicked is perhaps either not always consciously perceived or more fragile than generally reported in the scientific literature41. Finally, it should be noted that the key findings of this study showed remarkable effect sizes, suggesting that they may be relevant beyond mere academic interest.

There is evidence that people imitate the behaviors of those with whom they have ongoing relationships: parents42 and teachers43. There is also evidence that higher coordination of patient’s and therapist’s movement in psychotherapy dyads is associated with better outcome44. However, mimicry occurs spontaneously and unintentionally and it is very difficult to voluntary imitate other’s body posture, hand gestures or emotions during an interaction without being aware that the behavior is being copied45. As a consequence, using virtual agents of well-known person (i.e. referent from a clinical team) could constitute a promising augmentation to virtual reality social skills training intervention or job training interview, via the use of mimicking virtual agents. In addition, series of previous studies have shown that social cues, such as eye-contact17, and emotional facial expressions46, have the potential to modulate synchronization behavior in healthy participants. Further studies are needed to explore if such additional social cues implemented in virtual partners could increase synchronization behavior and by consequences act as a “social” cue in a mental disorder with severe social impairments and rejection.

Conclusion

First, our findings suggest that schizophrenia cannot be considered anymore as a disorder of imitation, particularly as regards behavioral synchronization processes in social interaction contexts. Secondly, our study demonstrated how virtual environments could be used to address important questions in the context of social disorders such as schizophrenia. From a clinical perspective, we believe that our results are very encouraging and have implications for VR training programs. Virtual reality environments have been increasingly used in the context of mental health treatment and within schizophrenia research during the last five years. Virtual reality, as a treatment approach, has demonstrated promise in treating psychotic symptoms particularly hallucination47, but also as an adjunct to social-skills training48 or job interview training49. As such, future virtual reality interventions could use mimicry as a real-time feedback signal to create more meaningful human-virtual agent interactions leading to increase patients’ engagement in VR-based treatment.

Methods

Participants

Nineteen outpatients with schizophrenia and nineteen healthy controls participated in the study. Two additional schizophrenia patients and two healthy participants did not complete the whole experiment. We recruited patients meeting DSM IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia in Montpellier University Hospital. Diagnosis of schizophrenia was established via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) by the treating psychiatrist. None were in the acute phase of psychosis. Inclusion criteria were being between 18 and 55 years of age, having a diagnosis of schizophrenia and being able to understand, talk and read French. Exclusion criteria were substance dependency other than cannabis or tobacco, substance abuse other than cannabis or alcohol, and co-morbid neurological disorder. Eighteen patients were medicated at clinically determined dosages. One patient was not taking medication. The mean dose of antipsychotic medication was equivalent to 540 mg/day of chlorpromazine (SD = 334.38)50. Controls were recruited from the general population with no personal lifetime history of any psychosis or affective disorders diagnosis (MINI)51. Controls with a family member with bipolar or schizophrenia disorders were excluded. All participants were native French speakers with a minimal reading level validated using the National Adult Reading Test (f-NART)52. All participants were right-handed as assessed by informal verbal inquiry. All participants provided written informed consent, prior to the experiment approved by the National Ethics Committee (CPP Sud-Méditerranée-III, Nîmes, France, #2009.07.03ter and ID-RCB-2009-A00513-54) and conforming to the Declaration of Helsinki. Accordingly with identifying information policies, written informed consent for publication of identifying information/images was obtained.

Clinical variables

In the schizophrenia sample, we administered the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale using the Structured Clinical Interview for the PANSS (SCI-PANSS). For this study, five of the analytically derived PANSS factor component scores53 were taken into account: Positive, Negative, Disorganization, Excitement and Emotional Distress (Table 3).

Rapport

No validated measures of rapport such as the Inclusion of the Other in the Self Scale (IOS)54 or the 6-item Willingness to Interact Questionnaire (WIQ)55 have been developed for CVEs. Thus, rapport during the interaction with the virtual agent was evaluated using self-reported measures based on previous studies using CVEs56 and on literature on interpersonal communication. The questionnaire was composed by three questions assessing positive rapport toward the virtual agent (i.e. “I felt comfortable while interacting with this virtual agent”, “I think this virtual agent is attractive”, “I like this agent”) and one question assessing willingness for future interactions adapted from the WIQ (“I want to interact with this virtual agent again in the future”). The questions were answered using a scale from −3 to +3, −3 being equals to “I do not agree al all”, 0 “more or less”, and +3 “I totally agree”. A rapport total score was also provided composed by the sum of the four questions.

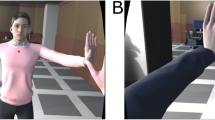

Procedure

The experiment was completed in two visits. Visit 1 involved completing informed consent, clinical interviews and questionnaires. Visit 2 occurred approximately 2 days later. It consisted on a virtual mimicry experiment. We designed an interactive protocol comprising two conditions, a mimicry and a no-mimicry condition, where participants stood up in front a photo-realistic 3D virtual agent displayed on a large TV screen (Fig. 2). During the interaction and the two experimental conditions, the virtual agent provided information about some healthy issues: physical activity levels, quality of diet and sleep and how to quit smoking. Texts were vocally delivered by the virtual agent using a computer-generated voice and were synchronized with the virtual agent motion. The motion of the virtual agent was pre-recorded by an actor whose upper-body movements (head, torso, arms and forearms) were tracked with 3D Inertial Measurement Units (IMU). In the mimicry condition, the virtual agent mimics the participants’ head and torso movements with a delay varying randomly between 0.5 s and 4 s, while in the no-mimicry condition, head and torso movements were pre-recorded. Every 5 s to 15 s, the virtual agent was scratching his arm to induce behavioral mimicry by the participant. During the interaction, participants had their movements recorded by six IMUs attached to their arms, forearms, torso and head (Fig. 3). One message was delivered per condition. Each condition lasted 300 s. Conditions were fully counterbalanced across participants. We measured in each condition the range of motion performed by the arms of the participant and the degree of behavioral synchronization between the virtual agent and the participant using the Forearms imitation motion.

Schematic illustration of the Imitative Virtual Reality Pipeline used in this experiment. 1. Participant motion is tracked using 6 IMUs (red cuboids); 2. Data are wireless transmitted in real-time to the computer; 3. Data are stored and also used for further computation; 4. Data from the different sensors are fused as a function of the mimicry condition, in the no-mimicry condition, only prerecorded motions (blue cuboids) are sent to the rendering process whereas in the mimicry condition, head and torso motions of the participant (red cuboids) are fused with other prerecorded sensors (blue cuboids) and send to the rendering; 5. Virtual environment is generated in realtime using Odysseus Studio and virtual agent’s voice is computer generated using MacVoiceOver. Voice was send to the participant through headphones.

Data Analysis

We measured the degree of synchronization behavior between the virtual agent and the participant using the Forearms imitation motion. 2 sets of 6 sensors (inertial measurement units) were used in this experiment. The first set corresponded to the virtual agent motion and the second set to the participant motion. Each sensor data called quaternion was recorded at a sampling frequency of 50 Hz (±1 Hz). Quaternions are simpler and more efficient representations of a rotation in a 3D space than Euler angles. Raw quaternions were normalized to ensure the robustness of further computations57. Normalized quaternions were then interpolated on a constant 50 Hz sampling rate using the Spherical Linear Quaternion Interpolation SLERP method58. We computed the amount of rotation between two samples using the natural metric for the rotation group (induced by the shortest path between its two elements); specifically we used its functional form based on the inner product of unit quaternions, which is most computationally efficient59. The amount of rotation was therefore unwrapped to avoid 2pi jumps in order to allow the next step of the analysis. Cross wavelet transform between the amount of rotation of the forearms of the participant and the virtual agent were computed59 giving rise to 3 time-frequency representations (Left forearm of the virtual agent versus Left forearm of the participant, Left forearm of the virtual agent versus Right forearm of the participant, and Right forearm of the virtual agent versus Right forearm of the participant). Cross wavelet transforms indicates the amount of synchronization between two time series for each sample in time and each period interval. Cross wavelet transforms were computed only in the range of period between 0.5 s to 8 s, corresponding to the range of behavioral mimicry usually described in the literature60. Significant areas (>0.95) of each of these 3 time-frequency representations were extracted and superimposed. Significant areas can be interpreted as synchronization levels significantly higher than random noise. The forearm imitation motion was finally calculated as a percentage of the trial where significant relationships between a movement of the virtual agent forearms and a movement of the participant forearms was detected.

Considering the statistical analysis, group differences and interactions were analysed with ANOVA tests. Post-hoc tests were used when the nature of the effects had to be specified. Size effects on our repeated ANOVA design have been reported using the partial eta squared61 ηp2, and interpreted following Cohen62 where 0.02 corresponds to a small effect, 0.13 to a medium effect and 0.26 to a large effect. When necessary, alpha value of significance was corrected using the Bonferroni procedure.

References

Chartrand, T. L. & Lakin, J. L. The antecedents and consequences of human behavioral mimicry. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 64, 285–308, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143754 (2013).

Jones, S. S. The development of imitation in infancy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 364, 2325–2335, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0045 (2009).

Lakin, J. L. & Chartrand, T. L. Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychol. Sci. 14, 334–339, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.14481 (2003).

Kupper, Z., Ramseyer, F., Hoffmann, H. & Tschacher, W. Nonverbal Synchrony in Social Interactions of Patients with Schizophrenia Indicates Socio-Communicative Deficits. PLoS One 10, e0145882, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145882 (2015).

Heyes, C. Automatic imitation. Psychol. Bull. 137, 463–483, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022288 (2011).

Chartrand, T. L. & Van Baaren, R. Human mimicry. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 41, 219–274, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)00405-X (2009).

Chartrand, T. L. & Bargh, J. A. The chameleon effect: the perception-behavior link and social interaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76, 893–910, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.6.893 (1999).

Maddux, W. W., Mullen, E. & Galinsky, A. D. Chameleons bake bigger pies and take bigger pieces: Strategic behavioral mimicry facilitates negotiation outcomes. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 44, 461–468, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.02.003 (2008).

Van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Kawakami, K. & Van Knippenberg, A. Mimicry and prosocial behavior. Psychol. Sci. 15, 71–74, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01501012.x (2004).

Cracco, E. et al. Automatic imitation: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 144, 453–500, https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000143 (2018).

Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston) (1977).

Vygotsky, L. S. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard university press (1980).

Bailenson, J. N., Yee, N., Patel, K. & Beall, A. C. Detecting digital chameleons. Comput. Hum. Behav. 24, 66–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.01.015 (2008).

Kulesza, W., Dolinski, D. & Wicher, P. Knowing that you mimic me: the link between mimicry, awareness and liking. Soc. Influence. 11, 68–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2016.1148072 (2016).

Wang, Y. & Hamilton, A. F. D. C. Social top-down response modulation (STORM): a model of the control of mimicry in social interaction. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, 153, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00153 (2012).

Edwards, L. A. A meta-analysis of imitation abilities in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. Res. 7, 363–380, https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1379 (2014).

Forbes, P. A. G., Pan, X. & Hamilton, A. F. D. C. Reduced Mimicry to Virtual Reality Avatars in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 46, 3788–3797, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2930-2 (2016).

Neufeld, J., Ioannou, C., Korb, S., Schilbach, L. & Chakrabarti, B. Spontaneous Facial Mimicry is Modulated by Joint Attention and Autistic Traits. Autism. Res. 9, 781–789, https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1573 (2016).

Kohler, C. G. et al. Dynamic evoked facial expressions of emotions in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Research. 105, 30–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2008.05.030 (2008).

Lee, J. S., Chun, J. W., Yoon, S. Y., Park, H.-J. & Kim, J.-J. Involvement of the mirror neuron system in blunted affect in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 152, 268–274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.043 (2014).

Park, S., Matthews, N. & Gibson, C. Imitation, simulation, and schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 698–707, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn048 (2008).

Matthews, N., Gold, B. J., Sekuler, R. & Park, S. Gesture imitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 39, 94–101, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr062 (2013).

Walther, S. et al. Nonverbal social communication and gesture control in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 338–345, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu222 (2015).

Thakkar, K. N., Peterman, J. S. & Park, S. Altered brain activation during action imitation and observation in schizophrenia: a translational approach to investigating social dysfunction in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 171, 539–548, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040498 (2014).

Haker, H. & Rössler, W. Empathy in schizophrenia: impaired resonance. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry. Clin. Neurosci. 259, 352–361, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-009-0007-3 (2009).

Simonsen, A., Fusaroli, R., Skewes, J. C., Roepstorff, A. & Campbell-Meiklejohn, D. Enhanced Automatic Action Imitation and Intact Imitation-Inhibition in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby006 (2018).

Putnam, K. M. & Kring, A. M. Accuracy and intensity of posed emotional expressions in unmedicated schizophrenia patients: vocal and facial channels. Psychiatry. Res. 151, 67–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2006.09.010 (2007).

Schwartz, B. L., Mastropaolo, J., Rosse, R. B., Mathis, G. & Deutsch, S. I. Imitation of facial expressions in schizophrenia. Psychiatry. Res. 145, 87–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2005.12.007 (2006).

Genschow, O. et al. Mimicry and automatic imitation are not correlated. PloS. One. 12, e0183784, 0.1371/journal.pone.0183784 (2017).

Green, M. F., Horan, W. P. & Lee, J. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 620–631, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn4005 (2015).

Parsons, T. D., Gaggioli, A. & Riva, G. Virtual Reality for Research in Social Neuroscience. Brain. Sci. 7, 42, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7040042 (2017).

Bailenson, J. N., Beall, A. C., Blascovich, J., Raimundo, M. & Weisbuch, M. Intelligent Agents Who Wear Your Face: Users’ Reactions to the Virtual Self. Intelligent Virtual Agents Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 86–99, https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-44812-8_8 (2001).

Garau, M., Slater, M., Pertaub, D. P. & Razzaque, S. The responses of people to virtual humans in an immersive virtual environment. Presence. 14, 104–116, https://doi.org/10.1162/1054746053890242 (2005).

Bailenson, J. N. & Yee, N. Digital chameleons: automatic assimilation of nonverbal gestures in immersive virtual environments. Psychol. Sci. 16, 814–819, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01619.x (2005).

Stevens, C. J. et al. Mimicry and expressiveness of an ECA in human-agent interaction: familiarity breeds content! Comput. Cogn. Sci. 2, 1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40469-016-0008-2 (2016).

Verberne, F. M. F., Ham, J., Ponnada, A. & Midden, C. J. H. Trusting Digital Chameleons: The Effect of Mimicry by a Virtual Social Agent on User Trust. Persuasive Technology Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 234–245, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37157-8_28 (2013).

Riehle, M. & Lincoln, T. M. Investigating the social costs of schizophrenia: Facial expressions in dyadic interactions of people with and without schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 127, 202–215, https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000319 (2018).

Bickmore, T. W. et al. Response to relational agent by hospital patients with depressive symptoms. Interact. Comput. 22, 289–298, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2009.12.001 (2010).

Rizzo, A. et al. Autonomous Virtual Human Agents for Healthcare Information Support and Clinical Interviewing. In Artificial Intelligence in Behavioral and Mental Health Care (ed David D. Luxton) 53–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-420248-1.00003-9 Academic Press, (2016).

Rizzo, A. et al. Automatic Behavior Analysis During a Clinical Interview with a Virtual Human. Stud. Health. Technol. Inform. 220, 316–322, https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-625-5-316 (2016).

Hale, J. & Hamilton, A. F. D. C. Testing the relationship between mimicry, trust and rapport in virtual reality conversations. Sci. Rep. 6, 35295, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35295 (2016).

Bernieri, F. J., Reznick, J. S. & Rosenthal, R. Synchrony, pseudosynchrony, and dissynchrony: Measuring the entrainment process in mother-infant interactions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 243–253, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.2.243 (1988).

Bernieri, F. J. Coordinated movement and rapport in teacher-student interactions. J. Nonverbal. Behav. 12, 120–138, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00986930 (1988).

Ramseyer, F., Kupper, Z., Caspar, F., Znoj, H. & Tschacher, W. Time-series panel analysis (TSPA): multivariate modeling of temporal associations in psychotherapy process. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 82, 828–838, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037168 (2014).

Mazza, M. et al. Could schizophrenic subjects improve their social cognition abilities only with observation and imitation of social situations? Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 20, 675–703, https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2010.486284 (2010).

Grecucci, A. et al. Emotional resonance deficits in autistic children. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 43, 616–628, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1603-z (2013).

Rus-Calafell, M., Garety, P., Sason, E., Craig, T. J. K. & Valmaggia, L. R. Virtual reality in the assessment and treatment of psychosis: a systematic review of its utility, acceptability and effectiveness. Psychol. Med. 48, 362–391, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001945 (2018).

Rus-Calafell, M., Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J. & Ribas-Sabaté, J. A virtual reality-integrated program for improving social skills in patients with schizophrenia: a pilot study. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 45, 81–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.09.002 (2014).

Smith, M. J. et al. Virtual reality job interview training and 6-month employment outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia seeking employment. Schizophr. Res. 166, 86–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.05.022 (2015).

Gardner, D. M., Murphy, A. L., O’Donnell, H., Centorrino, F. & Baldessarini, R. J. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am. J. Psychiatry. 167, 686–693, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060802 (2010).

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P. & Janavs, J. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 59, 22–33 (1998).

Mackinnon, A. & Mulligan, R. The estimation of premorbid intelligence levels in French speakers. Encephale. 31, 31–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-7006(05)82370-X (2005).

Van der Gaag, M. et al. The five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale II: a ten-fold cross-validation of a revised model. Schizophr Res. 85, 280–287, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.021 (2006).

Aron, A., Aron, E. N. & Smollan, D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 596–612, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596 (1992).

McCroskey, J. C. Reliability and validity of the willingness to communicate scale. Commun. Q. 40, 16–25, https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379209369817 (1992).

Stevens, B. L., Lewis, F. L. & Johnson, E. N. Aircraft Dynamics and Classical Control Design. Aircraft Control and Simulation: Dynamics, Controls Design, and Autonomous Systems. 250–376, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119174882.ch4 (2015).

Dam, E. B., Koch, M. & Lillholm, M. Quaternions, interpolation and animation. Tech. Rep. DIKU 98/5, Institute of Computer Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen Denmark. http://www.diku.dk/students/myth/quat.html (1998).

Huynh, D. Q. Metrics for 3D rotations: Comparison and analysis. J. Math. Imaging. Vis. 35, 155–164, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10851-009-0161-2 (2009).

Grinsted, A., Moore, J. C. & Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlin. Process. Geophys. 11, 561–566, https://doi.org/10.5194/npg-11-561-2004 (2004).

Eaves, D. L., Turgeon, M. & Vogt, S. Automatic imitation in rhythmical actions: kinematic fidelity and the effects of compatibility, delay, and visual monitoring. PLoS. One. 7, e46728, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046728 (2012).

Batschelet, E. Circular Statistics in Biology. Technometrics 24, 336–336 (1981).

Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, 1988).

Acknowledgements

This experiment was supported by a grant from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7 ICT 2011 Call 9) under grant agreement FP7-ICT-600610 ALTEREGO. We sincerely acknowledge the members of the AlterEgo consortium and more specifically Markus Miezal for his help in developing the acquisition system, and Mathieu Gueugnon and Zhong Zhao for their help in collecting part of the data. This work was supported by the European Project AlterEgo FP7 ICT 2.9 - Cognitive Sciences and Robotics, grant number 600610.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Raffard, R.N. Salesse, B.G. Bardy, L. Marin, D. Stricker and D. Capdevielle contributed in the acquisition of funding. All authors contributed to the original idea. S. Raffard, R.N. Salesse and D. Capdevielle contributed to the study design. C. Bortolon recruited and assessed the patients. J. Henriques, R.N. Salesse and D. Stricker developed the technology for the virtual agents. R.N. Salesse and C. Bortolon performed the statistical analysis. S. Raffard wrote the first draft. S. Raffard, R.N. Salesse and C. Bortolon prepared the final manuscript. S. Raffard and R.N. Salesse reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raffard, S., Salesse, R.N., Bortolon, C. et al. Using mimicry of body movements by a virtual agent to increase synchronization behavior and rapport in individuals with schizophrenia. Sci Rep 8, 17356 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35813-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35813-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Synchrony in triadic jumping performance under the constraints of virtual reality

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Study of Coordination Between Patients with Schizophrenia and Socially Assistive Robot During Physical Activity

International Journal of Social Robotics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.