Abstract

Here we present a new composite record from two well-dated speleothem records from two caves in Northern Morocco. The high-resolution record covers the last millennium allowing to detect multi-decadal to centennial periodicities. Over the industrial period, δ18O values of our speleothems are shown to be dominated by the main mode of decadal variability in the North Atlantic region: the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Statistical analyses confirm the previously reported multi-decadal variability related to the influence of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) in the region. High power and persistent centennial-scale periodicities, similar to the Vries-Suess 200-year solar cycle, are observed as well. Indeed, comparison between solar activity reconstructions and our record confirms the in-phase relationship on centennial time-scales. Low δ18O values, and hence negative phases of NAO that bring precipitation towards the Western Mediterranean, are observed during well-known solar minima periods. The results are consistent with previous models which describe low irradiance as a trigger for southward shifts of precipitation-bearing westerlies during winter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Western Mediterranean, located at the north-eastern side of the Azores High and hence under the direct influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)1,2, is considered as one of the most sensitive regions to drought3. Climate models anticipate more drought and reduced annual precipitation in this region in the future4,5.

At seasonal to interannual time scales, the NAO is indeed the main atmospheric phenomenon that modulates the strength and the direction of the westerly winds and consequently affects the climate patterns in the Western Mediterranean, with severe socio-economic and ecological consequences6. Previous studies have shown that the Western Mediterranean climate is highly influenced by the NAO, whereas positive and negative NAO phases result in droughts and higher than normal rainfall in the region1,2,7. Additionally, the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation (AMO) has been shown to impact climate in the North Atlantic region. Speleothem records in Morocco covering the last 1000 years have revealed the presence of multidecadal hydro-climate variability consistent with the AMO known periodicity8.

Information on climate variability in the Western Mediterranean remains however scarce due to the lack of long instrumental datasets. High-resolution paleoclimate reconstructions in this region are thus essential to increase our understanding of hydroclimate variability on various timescales and to discuss potential forcing mechanisms and related atmospheric circulation changes in the remote past beyond the industrial period.

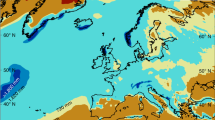

Speleothems can be precisely dated and provide high-resolution climate records of effective rainfall (i.e. the amount of precipitation that actually infiltrates into the soil) during the past9. Hence, stalagmites have been sampled from caves in Northern Morocco (Fig. 1), which is a key NAO region at the north-eastern side of the Azores Subtropical High. In this study, we present two new precisely dated high-resolution speleothem δ18O records (Cha2 and GP5) from Chaara and Piste caves respectively (Suppl. Text 1; Fig. S1). The purpose of this work is to provide new insights on decadal to centennial western Mediterranean hydro-climate variability and its relation with solar forcing during the last millennium.

Rainfall amount in Northwest Africa and Southwestern Europe (mm/month) during the winter (December–January–February; DJF) and the summer (June–July–August; JJA) seasons, calculated from the “TRMM 3B42 daily V7” data45 for the period 1998–2015. Locations of paleoclimate records discussed in the paper are indicated: Chaara cave (white circle), Piste cave (black circle13) and Ifoulki cave (yellow circle8).

Results and Discussion

GP5 and Cha2 speleothem records

The age model of the GP5 record is constructed using 23 Th/U dates, and the δ18O record covers the period ▯910–1960 AD with a short hiatus centered at approximately 960 AD. For the Cha2 record, the age model is based on 17 Th/U dates revealing that the sample spans the period 912–2000 AD with a hiatus from 1555 to 1736 AD (Suppl. Text 2; Fig. S2). The average age uncertainties are 8.6 and 6.5 years for GP5 and Cha2, respectively (Table S1). The growth rate of GP5 is higher than for Cha2 with 0.31 vs. 0.09 mm/yr, respectively. The δ18O sampling resolution is also relatively high in both records, with a mean resolution of 5 and 7.5 years for GP5 and Cha2, respectively. However, during a period of slow growth in the Cha2 record (1250–1460 AD), the δ18O sampling resolution drops off to 25 years. Therefore, we refrain from the interpretation of periodicities lower than 25 years in the statistical analyzes below.

The average δ18O values of GP5 and Cha2 records are −5.39‰ and −5.27‰ respectively. The δ18O records of both GP5 and Cha2 show similar trends and replicate very well (Fig. 2a,b). However, GP5 has a smaller δ18O amplitude compared to Cha2, which may be explained by longer water residence time and coincident mixing of several years of precipitation resulting in a smoothing effect10. The principal component analysis (PCA) between the GP5 and Cha2 δ18O time-series was performed to extract the common variability between both records. A composite record of GP5 and Cha2 δ18O records was also calculated (see Methods). The first component of the PCA (PC1) represents 67% of the common variability of both records. Furthermore, PC1 is almost identical to the composite of GP5 and Cha2 (Fig. 2c,d).

Comparison of the Cha2 (a) and GP5 (b) δ18O records with other paleo-records; (c) PC1 of Cha2 and GP5 δ18O records; (d) composite record of Cha2 and GP5 δ18O records; (e) IFK1 stalagmite δ18O record8; (f)tree-rings ScPDSI record12,13. Bold curves correspond to the 50-year moving average of each time-series.

Based on previous monitoring work carried out in the caves region11, modern precipitation δ18O values are well correlated to rainfall amount (r ≥ 0.7) on seasonal timescales, whereas winter rainfall amount is correlated to the NAO index (r = 0.66). The GP5 and Cha2 δ18O records are thus considered proxies for effective rainfall. Therefore, we use the composite record in the discussion below as a representative record of effective rainfall variability during the last millennium in Northern Morocco, whereas negative values reflect humid conditions and vice-versa.

The composite δ18O record shows substantial alternations of dry and humid conditions on decadal to centennial time-scales (Fig. 2d). The Medieval climate anomaly (MCA) and the Little Ice Age (LIA) are defined as ∼900–1350 AD and ∼1500–1850 AD, respectively, based on previous paleoclimate studies in Morocco8,12,13. The general trend of our δ18O composite record supports a previously published speleothem δ18O record from Ifoulki cave from southwestern Morocco8 (Fig. 2e). Taking into account the age uncertainties in both records and their different resolutions, more negative δ18O values prevailed during the first part of the MCA (~910–990 AD), the period from ~1270 AD to ~1310 AD with a peak centered around 1290 AD, the period from ~1430 AD to ~1510 AD with a peak centered around 1480 AD, and from the second part of the LIA to the early 20th century (~1680–1910 AD). On the opposite, more positive δ18O values prevailed in both records during the second part of the MCA (~1140–1260 AD and ~1310–1380 AD), the first part of the LIA (~1520–1680 AD) and during the 20th century with a positive peak centered around 1940 AD. However, the two records show an anti-phase around 1050 and 1780 AD.

The Cha2-GP5 δ18O composite record also shows some coherent variations with a tree-ring Self-calibrating Palmer Drought Severity Index (ScPDSI) record from Northern Morocco (Fig. 2f)12,13, especially after the MCA. A pronounced shift towards wetter conditions after 1400 AD is in phase with the onset towards more humid conditions recorded in the Cha2-GP5 record. During the MCA/LIA transition and the LIA, peaks of wet conditions (around 1480 AD, 1570 AD, 1700 AD, 1770 AD and 1850 AD) seem to be synchronous with negative δ18O values in the composite record on decadal time-scale. However, during the MCA, the ScPDSI shows overall drier conditions compared to the Cha2-GP5 record. These differences might be related to the different seasons recorded in Cha2-GP5 speleothems (winter) and the tree-rings ScPDSI (February–June).

North Atlantic climate variability

Previous studies based on instrumental and climate model data have shown that the Western Mediterranean climate is modulated by rainfall variability linked to the NAO1,2. Intervals with increased rainfall in Morocco are indeed related to negative phases of the NAO at inter-annual timescale. At decadal timescale, both AMO and NAO low frequency modulation exert a large influence on hydro-climate variations in the North Atlantic sector.

Comparison of our record with instrumental NAO index during the common period of both records (1850–2000 AD) shows a high consistency (r = 0.63; Fig. S3), taking into account the age uncertainties in our speleothems records. Specifically, phases with a negative NAO index coincide with lower speleothem δ18O values, and hence wet conditions. For the last millennium, to a good extent, the lower δ18O values in our record (Fig. 3a) are synchronous with negative phases of the NAO (Fig. 3b,c) as shown by comparison with the NAO index reconstructions6,14. This is especially relevant for the negative peaks centered around 1050 AD, 1480 AD, 1610 AD and 1770 AD. However, several inconsistencies on longer time-scales can also be observed suggesting that another mechanism is involved as well in the region (e.g. AMO).

Positive AMO conditions were found to favor extensive cyclonic pressure anomalies over the Western Mediterranean, especially during the winter season15. Moreover, McCarthy et al.16 showed that the NAO influences the AMO through changes of the ocean circulation in the North Atlantic inter-gyre region. A positive AMO phase tends to result in more frequent negative NAO with a large influence on precipitation15,17. This would result in more moisture in-flow and wetter conditions in the Western Mediterranean during the winter season. However, comparison with the reconstructed AMO index18 (Fig. 3d) shows that the anti-phase relationship between NAO and AMO seems to be more complicated during the last millennium. Nevertheless, Redfit spectral analysis of our record (Fig. S4a) reveals significant multi-decadal periodicities similar to AMO. Other NAO reconstructions have shown similar periodicities to AMO for the last millennium as well14,19. Our findings are thus in line with former studies and brings further evidence that the multi-decadal variability of the NAO is the result of a link to AMO19,20. The multi-decadal imprint of AMO over the last millennium has recently been observed in a speleothem δ18O record from a cave in south-western Morocco8. The centennial-scale variability shown by the spectral analysis in the North Atlantic region has so far only been signaled in a few studies. A NAO-type 170-year quasi-periodicity was observed in a laminated sediment record from Greenland19. This variability has been suggested to be the result of centennial-scale solar forcing21. Recently, a multi-proxy lake record from the Middle Atlas in Morocco, also revealed that a multi-centennial-scale NAO-type pattern, related to solar variability, modulates Western Mediterranean climate22.

Linkage to solar forcing

Redfit spectral analysis of our δ18O composite record shows strong centennial-scale periodicities at 199–174 years and 107–100 years, significant at the 95% confidence level. The 199–174 year periodicities in the spectral analysis are close to the Vries-Suess solar cycle23. Similar high power periodicities around 200 years were also reported in a speleothem record in Southwestern Morocco8. These results suggest that δ18O variability responds to solar forcing through NAO as suggested above. High power 200-year periodicities were also recorded in the CaCO3 record from Lake Sidi Ali in northern Morocco22. Periodicities similar to the 100-70 year Gleissberg cycle24 can also be identified in our record and in the ScPDSI record (Fig. S4b). However, the ScPDSI record does not show significant periodicities over 200 years. This might imply that the 200-year cycle is mainly recorded in the winter season, rather than the February-June season.

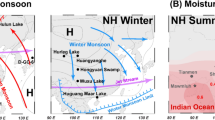

The NAO-response to solar activity has been observed and modeled in a number of studies25,26,27,28,29. In particular, the atmosphere–ocean response30,31 and the weakening of westerly winds during winter at times of solar minima are associated with patterns similar to a negative phase of the NAO32,33. The mechanism between the NAO and solar forcing has been proposed by a number of studies, which describe that at times of reduced solar irradiance, the downward-propagating effects triggered by changes in stratospheric ozone induce a cooling of the high northern latitude atmosphere and a southward shift of the Northern Subtropical Jet29,30,34,35.

Wavelet analysis of the composite record further indicates that the robust 200-year cycle is pervasive throughout the entire record (Fig. S5). Importantly, a clear in-phase relationship is observed between our composite δ18O record and the widely used total solar irradiance (TSI) reconstruction36 and a recently revised solar modulation record37. Especially, the Spörer minimum coincides with the lowest δ18O value in our record. The negative peaks during the Oort, Wolff, Maunder and Dalton solar minima also seem to coincide with more negative speleothem δ18O values in Morocco. However, the Maunder and Dalton minima are less pronounced in the composite record (Fig. 4a–c). When taking age uncertainties into account, the Ifoulki cave δ18O record from Morocco8 also shows low δ18O value during grand solar minima, with exception to the Oort minimum which is less noticeable (Fig. 4d). The tree-rings ScPDSI (Fig. 4e) also reveals wet conditions during the grand solar minima. However, given the robust age model of the ScPDSI record, only the low solar activity peaks during Oort and Spörer minima seem to be synchronized with wet conditions. This reinforces our assumption that the centennial solar forcing is mainly captured during the winter season.

Comparison of the solar modulation reconstruction37 (a) and the total solar irradiance (TSI) reconstruction36 (b) with the Cha2-GP5 δ18O composite record (c), the Ifoulki cave (IFK1) stalagmite δ18O record8 (d) and the tree-rings ScPDSI record12,13 (e). Blue shading indicates periods of low solar activity: Oort minimum (1010–1090 AD), Wolf minimum (1280–1350 AD), Spörer minimum (1450–1550 AD), Maunder minimum (1645–1715 AD) and the Dalton minimum (1790–1820 AD). Black arrows indicate peaks of low solar activity and their corresponding peaks of wet conditions in Morocco.

In addition, the cross-wavelet analyzes of our record and both solar reconstructions shows a clear correlation with the highest power at periodicities of approximately 200 years (Fig. 5a,b). Strong power is also observed on the multi-decadal timescale, yet the phasing oscillates between both records, which might be suggestive of a less consistent influence of the solar signal on multi-decadal time scales. We therefore focus on the 200-year time scale variability, which we demonstrated has the most coherent and persistent response to solar forcing. This is consistent with paleoclimate data38 which suggest a shift toward low NAO state during periods of reduced solar forcing. Moreover, during the Maunder Minimum for example, model results and reconstructions suggest that solar-forced regional climate changes appeared predominantly as a shift towards a more negative NAO index38,39. Such negative phases of NAO-like conditions are associated with a southward shift of the northern subtropical jet, which drives the moisture flow towards the Western Mediterranean.

Conclusions

A speleothem δ18O composite record of the last millennium from two high-resolution Th/U dated stalagmites from two caves in Morocco is presented and discussed. The link between NAO/AMO activity and hydro-climate variability described by our record is confirmed by previous monitoring work and historical data. Hence, the δ18O variability is interpreted as a result of the combination of NAO and AMO.

Our δ18O record reveals centennial cycles similar to well-known solar cycles. Interestingly, a 200-year cycle persists throughout the entire record. Comparison with solar forcing reconstructions shows a striking consistency, and the cross-wavelet further shows a clear correlation with the highest power at periodicities similar to the Vries-Suess solar cycle. Low irradiance periods during well know solar minima periods coincide with negative δ18O peaks, consistent with model results that suggest that the NAO responds to solar activity.

Hence, we have provided new proxy evidence for centennial-scale solar forcing. We also highlight the potential of speleothems and the relevance of using high resolution proxy records with robust age models to investigate potential teleconnections and coupling with forcing mechanisms to confirm climate models.

Methods

Two new high resolution δ18O records from two aragonite stalagmites are presented. The two stalagmites were collected in 2010 from two adjacent caves that are only a few 100 m apart (33°57′21″N, 4°14′46″ W, 1260 m.a.s.l.). Stalagmite Cha2 was collected below an active drip site at 300 m distance of the entrance of Chaara cave and is 60 cm long. Stalagmite GP5 was collected below an active drip site at 50 m distance of the entrance of Grotte de Piste13 and is 78 cm long (Fig. S6).

The present day climate of the cave sites is characterized by average annual rainfall around 1267 mm at Bab Bou Idir station with 85% of rainfall amount falling during the winter season (Suppl. Text 1).

The stalagmite chronologies are based on 17 Th/U dates for Cha2 and 23 Th/U dates and the detection of the 14C bomb peak for GP5 (Suppl. Text 2). Age depth modeling was performed using the StalAge algorithm40. Based on the detection of the 14C bomb peak in stalagmite GP5, the year 1964 was assigned to 0.2 mm distance from top13.

Our paleoclimate records are based on 123 δ18O samples from Cha2 and 204 samples from GP5 using conventional Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometers (Suppl. Text 3). The oxygen isotope values were corrected using a calcite acid fractionation factor, but were converted to aragonite oxygen isotope values after evaluation with the factor41.

In order to extract the common variability between Cha2 and GP5 records, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA). For this purpose, time-series were interpolated to create annual resolution and then normalized. A composite record was also constructed by averaging the normalized δ18O values obtained from the time series of Cha2 and GP5. In order to detect the most significant periodicities documented in time-series, REDFIT42 and spectral analysis were carried out using the PAST software43. Wavelet and cross-wavelet analyses44 were also performed to check significant periodicities and high common power between our records and other paleoclimate reconstructions.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this research article can be downloaded from the NOAA paleoclimate database https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/25970.

Change history

16 July 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Knippertz, P., Christoph, M. & Speth, P. Long-term precipitation variability in Morocco and the link to the large-scale circulation in recent and future climates. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 83, 67–88 (2003).

López-Moreno, J. I. et al. Effects of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) on combined temperature and precipitation winter modes in the Mediterranean mountains: observed relationships and projections for the 21st Century. Glob. Planet. Change. 77, 62–76 (2011).

Giorgi, F. & Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob. Planet. Change. 63(2–3), 90–104 (2008).

Bouchaou, L., Tagma, T., Boutaleb, S., Hssaisoune, M. & El Morjani, Z. E. A. Climate change and its impacts on groundwater resources in Morocco: the case of the Souss-Massa basin. In: Climate Change Effects on Groundwater Resources. (ed. IAH/Taylor & Francis) 129–144 (Taylor & Francis, 2011).

Abahous, H., Ronchail, J., Sifeddine, A., Kenny L. & Bouchaou L. Trend and change point analyses of annual precipitation in the Souss-Massa Region in Morocco during 1932–2010. Theor. Appl. Climatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-017-2325-0 (2017).

Ortega, P. et al. A model-tested North Atlantic Oscillation reconstruction for the past millennium. Nature. 523, 71–74 (2015).

Ait Brahim, Y. et al. Elucidating the climate and topographic controls on stable isotope composition of meteoric waters in Morocco, using station-based and spatially-interpolated data. J. Hydrol. 543(Part B), 305–315 (2016).

Ait Brahim, Y. et al. Speleothem records decadal to multidecadal hydroclimate variations in southwestern Morocco during the last millennium. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 476, 1–10 (2017).

Domínguez-Villar, D., Wang, X., Cheng, H., Martín-Chivelet, J. & Edwards, L. Α high-resolution late Holocene speleothem record from Kaite Cave, northern Spain: δ18O variability and possible causes. Quat Int. 187, 40–51 (2008).

Mischel, S. A., Scholz, D. & Spötl, C. δ18O values of cave drip water: a promising proxy for the reconstruction of the North Atlanic Oscillation? Clim. Dyn. 45, 3035–3050 (2015).

Wassenburg, J. A. et al. Major reorganization of the North Atlantic Oscillation during Early Holocene deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 9, 602–605 (2016).

Esper, J., Frank, D., Buntgen, U., Verstege, A. & Luterbacher, J. Long-term drought severity variations in Morocco. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, 5 (2007).

Wassenburg, J. A. et al. Moroccan speleothem and tree ring records suggest a variable positive state of the North Atlantic Oscillation during the Medieval Warm Period. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 375, 291–302 (2013).

Trouet, V. et al. Persistent positive North Atlantic Oscillation mode dominated the medieval climate anomaly. Science. 324, 78–80 (2009).

Knight, J. R., Folland, C. K. & Scaife, A. A. Climate impacts of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L17706 (2006).

McCarthy, G. D., Haigh, I. D., Hirschi, J. J. M., Grist, J. P. & Smeed, D. A. Ocean impact on decadal Atlantic climate variability revealed by sea-level observations. Nature 521(7553), 508–510 (2015).

Peings, Y. & Magnusdottir, G. Response of the wintertime Northern Hemisphere atmospheric circulation to current and projected Arctic Sea ice decline: A numerical study with CAM5. J. Climate. 27, 244–264 (2014).

Mann, M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the little ice age and medieval climate anomaly. Science. 326, 1256–1260 (2009).

Olsen, J., Anderson, J. N. & Knudsen, M. F. Variability of the North Atlantic Oscillation over the past 5200 years. Nat. Geosci. 5, 808–812 (2012).

Gastineau, G. & Frankignoul, C. Influence of the North Atlantic SST variability on the atmospheric circulation during the twentieth century. J. Climate. 28(4), 1396–1416 (2014).

Ojala, A. E. K., Launonen, I., Holmstrom, L. & Tiljander, M. Effects of solar forcing and North Atlantic oscillation on the climate of continental Scandinavia during the Holocene. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 112, 153–171 (2015).

Zielhofer, C. et al. Atlantic forcing of Western Mediterranean winter rain minima during the last 12,000 years. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 157, 29–51 (2017).

Suess, H. E. The radiocarbon record in tree rings of the last 8000 years. Radiocarbon. 22, 200–209 (1980).

Gleissberg, W. The eighty-year sunspot cycle. J. Br. Astron. Assoc. 68, 148–152 (1958).

Swingedouw, D. et al. Natural forcing of climate during the last millennium: fingerprint of solar variability. Clim. Dyn. 36, 1349–1364 (2011).

Scholz, D. et al. Holocene climate variability in north-eastern Italy: potential influence of the NAO and solar activity recorded by speleothem data. Clim. Past. 8, 1367–1383 (2012).

Gray, L. J. et al. A lagged response to the 11 year solar cycle in observed winter Atlantic/European weather patterns. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 13,405–413,420 (2013).

Gray, L. J., Woollings, T. J., Andrews, M. & Knight, J. Eleven-year solar cycle signal in the NAO and Atlantic/European blocking. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 142, 1890–1903 (2016).

Yukimoto, S., Kodera, K. & Thiéblemont, R. Delayed North Atlantic Response to Solar Forcing of the Stratospheric Polar Vortex. SOLA. 13, 53–58 (2017).

Thiéblemont, R., Matthes, K., Omrani, N.-E., Kodera, K. & Hansen, F. Solar forcing synchronizes decadal North Atlantic climate variability. Nature Commun. 6, 8268 (2015).

van Loon, H. & Meehl, G. A. Interactions between externally forced climate signals from sunspot peaks and the internally generated Pacific Decadal and North Atlantic Oscillations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 161–166 (2014).

Ineson, S. et al. Solar forcing of winter climate variability in the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Geosci. 4, 753–757 (2011).

Moffa-Sanchez, P., Born, A., Hall, I. R., Thornalley, D. J. R. & Barker, S. Solar forcing of North Atlantic surface temperature and salinity over the past millennium. Nature Geosci. 7, 275–278 (2014).

Bond, G. et al. Persistent solar influence on North Atlantic climate during the Holocene. Science. 294, 2130–2136 (2001).

Kodera, K. Solar cycle modulation of the North Atlantic Oscillation: Implication in the spatial structure of the NAO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 1218 (2002).

Steinhilber, F., Beer, J. & Frohlich, C. Total solar irradiance during Holocene. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L19704 (2009).

Muscheler, R., Adolphi, F., Herbst, K. & Nilsson, A. The revised sunspot record in comparison to cosmogenic radio-nuclide-based solar activity reconstructions. Solar Phys. 291, 3025–3043 (2016).

Shindell, D. T., Schmidt, G. A., Miller, R. L. & Rind, D. Northern Hemisphere winter climate response to greenhouse gas, ozone, solar, and volcanic forcing. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 7193–7210 (2001).

Rind, D. et al. The relative importance of solar and anthropogenic forcing of climate change between the Maunder Minimum and the present. J. Clim. 17, 906–929 (2004).

Scholz, D. & Hoffmann, D. L. StalAge – an algorithm designed for construction of speleothem age models. Quat. Geochronol. 6, 369–382 (2011).

Kim, S.-T., Mucci, A. & Taylor, B. E. Phosphoric acid fractionation factors for calcite and aragonite between 25 and 75 degrees C: Revisited. Chem. Geol. 246, 135–146 (2007).

Schulz, M. & Mudelsee, M. REDFIT: estimating red-noise spectra directly from unevenly spaced paleoclimatic time-series. Comput. and Geosci. 28, 421–426 (2002).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electronica. 4, 9 (2001).

Grinsted, A., Jevrejeva, S. & Moore, J. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 11, 561–566 (2004).

Huffmann, G. J. & Bolvin D. T. Real-Time TRMM Multi-Satellite Precipitation Analysis Data Set Documentation. pmm.nasa.gov/data-access/downloads/trmm (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored thanks to the National Natural Science Foundation of China grants (NSFC 41731174 and NSFC 41561144003), the German Research Foundation (DFG: WA3532/1-1 and IM44/1) and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF Grant 1702816). We would like to express our deep gratitude to Dr. Myriam Khodri for the discussion about NAO and AMO influence in the Western Mediterranean region. We would also like to thank Professor El Hassane Beraaouz and the Associations of Speleologists of Agadir (ASA and ASS) for their help with the field work, Alyne Barros for her help with stable isotope analyses, and Dr. Raimund Muscheler for sharing their solar forcing reconstruction data. We thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.A.B. and J.A.W. prepared the manuscript. Y.A.B. and J.A.W. carried out δ18O analyses, Th/U dating and XRD analyses. F.W.C., H.C., D.S., R.L.E., and K.P.J. provided lab support. A.S., L.B., J.A.W., F.W.C and H.C. carried out the fieldwork. H.C. directed the project. E.P.D. and all authors provided comments on the manuscript and assisted with discussions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ait Brahim, Y., Wassenburg, J.A., Cruz, F.W. et al. Multi-decadal to centennial hydro-climate variability and linkage to solar forcing in the Western Mediterranean during the last 1000 years. Sci Rep 8, 17446 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35498-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35498-x

This article is cited by

-

Iberian hydroclimate variability and the Azores High during the last 1200 years: evidence from proxy records and climate model simulations

Climate Dynamics (2023)

-

Twentieth-century Azores High expansion unprecedented in the past 1,200 years

Nature Geoscience (2022)

-

Split westerlies over Europe in the early Little Ice Age

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Palynological evidence from a sub-alpine marsh of enhanced Little Ice Age snowpack in the Marrakech High Atlas, North Africa

Vegetation History and Archaeobotany (2022)

-

Hydro-climate characteristics of the karst system of Wintimdouine cave (Western High Atlas, Morocco): monitoring and implications for paleoclimate research

Environmental Earth Sciences (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.